Valley Fever on the Rise—Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Sites

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Isolation of Bacteria and Fungi

2.4. Challenge Assays

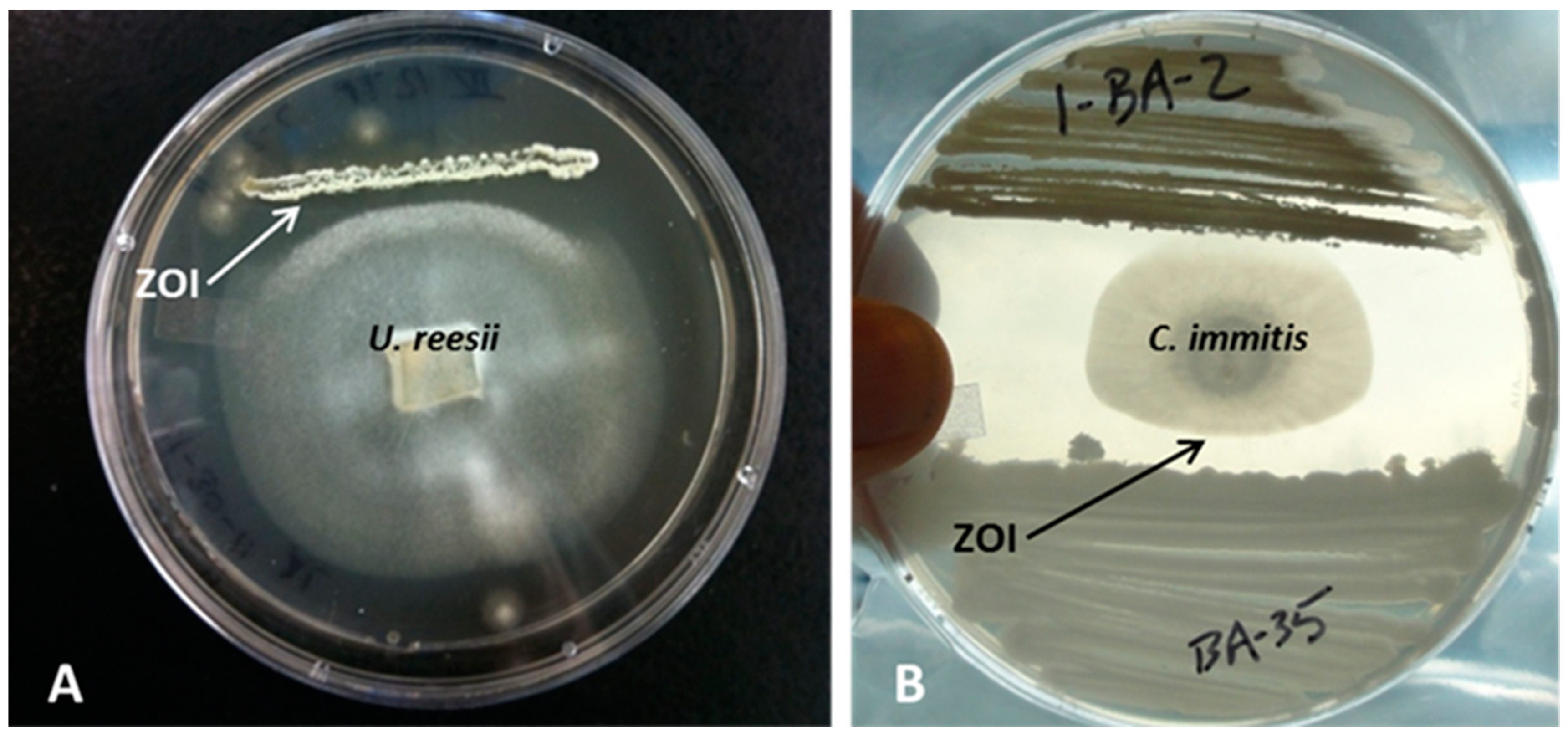

- Strongly antifungal: an inhibition zone of several mm appeared between fungi and bacteria. The fungus was unable to overgrow the bacteria.

- Weakly antifungal: the density of the fungal mycelium was lower toward the bacterial area, whereas all bacteria free space on the plate was covered with a thick fungal mycelium. The fungal growth adjacent to the bacterial growth was also slowed down considerably.

2.5. Heat and Salt Tolerance of Anti-Coccidioides Bacterial Isolates

2.6. DNA Extraction from Bacterial and Fungal Pure Cultures and PCR

2.7. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of rDNA Fragments

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Bacterial and Fungal Pure Cultures

3.2. Challenge Assays

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationships of Bacterial Isolates with Anti U. reesii and Anti-C. Immitis Properties

3.4. Heat and Salt Tolerance of Anti-Coccidioides Bacterial Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, M.C.; Koenig, G.; White, T.; San-Blas, G.; Negroni, R.; Alvarez, I.G.; Wanke, B.; Taylor, J.W. Biogeographic range expansion into South America by Coccidioides immitis mirrors New World patterns of human migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4558–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.C.; Koenig, G.L.; White, T.J.; Taylor, J.W. Molecular and phenotypic description of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov., previously recognized as the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia 2002, 94, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Marsden-Haug, N.; Hurst, S.; Hill, H.; Gade, L.; Driebe, E.M.; Ralston, C.; Roe, C.; Barker, B.M.; Goldoft, M.; et al. Valley Fever: Finding new places for an old disease: Coccidioides immitis found in Washington State soil associated with recent human infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 60, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, K.; Thompson, G.R., III; Deresinski, S.; Chiller, T. Mycotic infections acquired outside areas of known endemicity, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 11, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorris, M.E.; Cat, L.A.; Zender, C.S.; Treseder, K.K.; Randerson, J.T. Coccidioidomycosis dynamics in relation to climate in the southwestern United States. GeoHealth 2018, 2, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, C.W. Isolation of Coccidioides from soil and rodents. Publ. Health Rep. 1942, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rocío Reyes-Montes, M.; Pérez-Huitrón, M.A.; Ocaña-Monroy, J.L.; Frías-De-León, M.G.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Arenas, R.; Duarte-Escalante, E. The habitat of Coccidioides spp. and the role of animals as reservoirs and disseminators in nature. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Benedict, K.; Park, B.J.; Thompson, G.R., III. Coccidioidomycosis: Epidemiology. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 5, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.S.; Bultman, M.W.; Johnson, S.M.; Papagianis, D.; Zaborsky, E. Coccidioides niches and habitat parameters in the Southwestern United States. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1111, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Feature 24/7 Saving Lives, Protecting People). Valley Fever: Awareness is Key. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/ValleyFever/ (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- Tabnak, F.; Knutson, K.; Cooksey, G.; Nguyen, A.; Vugia, D. Epidemiologic Summary of Coccidioidomycosis in California; California Department of Public Health, Center for Infectious Diseases, Division of Communicable Disease Control: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/CocciEpiSummary2016.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2017).

- Cooksey Sondermeyer, G.; Nguyen, A.; Knutson, K.; Tabnak, F.; Benedict, K.; McCotter, O.; Jain, S.; Vugia, D. Notes from the field: Increase in coccidioidomycosis—California, 2016. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, M. The Fungal Kingdom: Diverse and Essential Roles in Earth’s Ecosystem. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). In Proceedings of the ASM Conference Proceedings, Washington, DC, USA, 23–26 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, M.; Jackson, B.R.; McCotter, O.; Benedict, K. Coccidioidomycosis Outbreaks, United States and Worldwide, 1940–2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondermeyer, G.; Lee, L.; Gilliss, D.; Tabnak, F.; Vugia, D. Coccidioidomycosis-associated hospitalizations, California, USA, 2000–2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgiani, J. Geography, climate, dust, and disease: Epidemiology of Valley Fever (coccidioidomycosis) and ways it might be controlled. In Fungal Diseases, a Threat to Humans, Animals, and Plant Health; Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, D.; Durán Graeff, L.A.; Vehreschild, M.J.; Wisplinghoff, H.; Ziegler, M.; Vehreschild, J.J.; Liss, B.; Hamprecht, A.; Köhler, P.; Racil, Z.; et al. FungiScope™—Global Emerging Fungal Infection Registry. Mycoses 2017, 60, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hector, R.F.; Rutherford, G.W.; Tsang, C.A.; Erhart, L.M.; McCotter, O.; Anderson, S.M.; Komatsu, K.; Tabnak, F.; Vugia, D.J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The public health impact of coccidioidomycosis in Arizona and California. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2011, 8, 1150–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swatek, F.E. Ecology of Coccidioides immitis. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1970, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, G.H.; Swatek, F.E. Soil Ecology of Coccidioides immitis at Amerindian Middens in California. Appl. Microbiol. 1974, 27, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Egeberg, R.O.; Ely, F. Coccidioides immitis in the soil of the Southern SanJoaquin Valley. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1956, 231, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauer, A.; Baal, J.D.; Baal, J.C.; Verma, M.; Chen, J.M. Detection of Coccidioides immitis in Kern County, California, by multiplex PCR. Mycologia 2012, 104, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranzoni, V. Fungi isolated in culture from soils of the Sonoran Desert. Mycologia 1968, 60, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, G.F. Some fungi isolated with Coccidioides immitis from soils of endemic areas in California. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club. 1968, 95, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeberg, R.O.; Elconin, A.E.; Egeberg, M.C. Effect of salinity and temperature on Coccidioides immitis and three antagonistic soil saprophytes. J. Bacteriol. 1964, 88, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paul, E.A. Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, H.F.; Classen, A.T.; Austin, E.E.; Norby, R.J.; Schadt, C.W. Soil microbial community responses to multiple experimental climate change drivers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurburg, S.D.; Nunes, I.; Stegen, J.C.; Le Roux, X.; Priemé, A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Salles, J.F. Autogenic succession and deterministic recovery following disturbance in soil bacterial communities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, R.G. Enzyme activity in soil: Location and a possible role in microbial ecology. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1982, 14, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchman, D.L. Processes in Microbial Ecology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, W.; Folman, L.B.; Summerbell, R.C.; Boddy, L. Living in a fungal world: Impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köberl, M.; Müller, H.; Ramadan, E.M.; Berg, G. Desert farming benefits from microbial potential in arid soils and promotes diversity and plant health. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duineveld, B.M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Keijzer, A.; van Elsas, J.D.; van Veen, J.A. Analysis of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of Chrysanthemum via Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA as well as DNA fragments coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, A.J.; Strap, J.L.; Knotek-Smith, H.M.; Crawford, D.L. Studies on the microbial populations of the rhizosphere of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata). J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 31, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, J.M.; Dar, N.A.; Bhat, T.A.; Bhat, A.H.; Bhat, M.A. Commercial biocontrol agents and their mechanism of action in the management of plant pathogens. Int. J. Mod. Plant Anim. Sci. 2013, 1, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J. Bacterial inhibition of fungal growth and pathogenicity. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 1999, 11, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, M.K.; Salake, A.B.; Chothe, A.S.; Dudhe, P.B.; Watode, R.P.; Mukta, M.S.; Gadhwe, S. The biology and chemistry of antifungal agents: A review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5678–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duijff, B.J.; Recorbet, G.; Bakker, P.A.H.; Loper, J.E.; Lemanceau, P. Microbial antagonism at the root level is involved in the suppression of Fusarium wilt by the combination of non-pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum Fo47 and Pseudomonas putida WCS358. Biol. Control 1999, 89, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.; Gunnewiek, P.J.; Lafeber, P.; Janse, J.D.; Spit, B.E.; Woldendorp, J.W. Anti-fungal properties of chitinolytic dune soil bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.; Verheggen, P.; Klein Gunnewiek, P.J.A.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; van Veen, J.A. Microbial community composition affects soil fungistasis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.; Défago, G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, R.; Warmink, J.A.; Boersma, H.; Van Elsas, J.D. Mechanisms that promote bacterial fitness in fungal-affected soil microhabitats. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 71, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey-Klett, P.; Burlinson, P.; Deveau, A.; Barret, M.; Tarkka, M.; Sarniguet, A. Bacterial-fungal interactions: Hyphens between agricultural, clinical, environmental, and food microbiologists. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 583–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.U.; Zhang, M.; Yang, P.; van Elsas, J.D. The interactions of bacteria with fungi in soil: Emerging concepts. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 89, pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, W. Upscaling of fungal–bacterial interactions: From the lab to the field. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 37, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R. Soil Isolation and Molecular Identification of Coccidioides immitis. Master’s Thesis, California State College, Long Beach, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Sørheim, R.; Torsvik, V.L.; Goksøyr, J. Phenotypical divergences between populations of soil bacteria isolated on different media. Microbiol. Ecol. 1989, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, C. Über die isolierte Färbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trockenpräparaten. Fortschritte der Medizin 1884, 2, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.; Sigler, L.; Cole, G.T. Evidence for a phylogenetic connection between Coccidioides immitis and Uncinocarpus reesii (Onygenaceae). Microbiology 1994, 140, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpton, T.J.; Stajich, J.E.; Rounsley, S.D.; Gardner, M.J.; Wortman, J.R.; Jordar, V.S.; Maiti, R.; Kodira, C.D.; Neafsey, D.E.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, T.N. Identification and characterization of genes found in Coccidioides spp. but absent in nonpathogenic Onygenales. bioRxiv 2018, 413906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.N.; James, T.Y.; Lauer, A.; Simon, M.A.; Patel, A. Amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is inhibited by the cutaneous bacteria of amphibian species. Ecohealth 2006, 3, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.H.; Walke, J.B.; Murrill, L.; Woodhams, D.C.; Reinert, L.K.; Rollins-Smith, L.A.; Burzynski, E.A.; Umile, T.P.; Minbiole, K.P.C.; Belden, L.K. Phylogenetic distribution of symbiotic bacteria from Panamanian amphibians that inhibit growth of the lethal fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 1628–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saita, K.; Nagaoka, S.; Shirosaki, T.; Horikawa, M.; Matsuda, S.; Ihara, H. Preparation and characterization of dispersible chitosan particles with borate crosslinking and their antimicrobial and antifungal activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 349, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, H.; Krsek, M.; Baker, P.; Smalla, K.; Wellington, E.M.H. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3233–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, U.; Rogall, T.; Blocker, H.; Emde, M.; Bottger, E. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 7843–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E.; Liesack, W. Nucleic acids and classification. In Handbook of New Bacterial Systematics; Goodfellow, M., O’Donnell, A.G., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1993; pp. 152–189. ISBN 10 0471929069. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K.J.; Rygiewicz, P.T. Fungal-specific PCR primers developed for analysis of the ITS region of environmental DNA extracts. BMC Microbiol. 2005, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 49, 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedges, S.B. The number of replications needed for accurate estimation of the bootstrap P value in phylogenetic studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992, 9, 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, M.A. The ecological role of biodiversity in agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1999, 74, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.J.A.; Booij, C.J.H.; Tscharntke, T. Sustainable pest regulation in agricultural landscapes: A review on landscape composition, biodiversity and natural pest control. Proc. R. Soc. B 2006, 273, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shennan, C. Biotic interactions, ecological knowledge and agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2008, 363, 717–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elconin, A.F.; Egeberg, R.O.; Egeberg, M. Significance of soil salinity on the ecology of Coccidioides immitis. J. Bacteriol. 1964, 87, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swatek, F.E.; Omieczynski, D.T.; Plunkett, O.A. Coccidiodes immitis in California. In Coccidioidomycosis, Papers from the Second Symposium on Coccidioidimycosis; Ajello, L., Ed.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1967; pp. 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, P.; Baker, K.F.; Waterworth, Y. Bacteria and actinomycetes antagonistic to fungal root pathogens in Australian soils. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1971, 24, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.L.; Lynch, J.M.; Whipps, J.M.; Ousley, M.A. Isolation and characterization of actinomycete antagonists of a fungal root pathogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 3899–3905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Schmid, M.; Hartmann, A.; Tripathia, A.K. Diversity of 16S-rRNA and nifH genes derived from rhizosphere soil and roots of an endemic drought tolerant grass, Lasiurus sindicus. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, A.; Simon, M.A.; Banning, J.L.; André, E.; Duncan, K.; Harris, R.N. Common cutaneous bacteria from the eastern red-backed salamander can inhibit pathogenic fungi. Copeia 2007, 1, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, S.U.; Sudha, S.; Jeslin, V.A.; Manisha, S. Isolation, identification and extraction of antimicrobial compounds produced by Streptomyces spp. from terrestrial soil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 15, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, J.T.; Konopka, A. Measurements of in situ activities of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 1985, 39, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raijmakers, J.M.; Vlami, M.; de Souza, J.T. Antibiotic production by bacterial biocontrol agents. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 81, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, P.; O’Sullivan, D.J.; Simpson, P.; Glennon, J.D.; O’Gara, F. Isolation of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from a fluorescent pseudomonad and investigation of physiological parameters influencing its production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ownley, B.H.; Weller, D.M.; Thomashow, L.S. Influence of in situ and in vitro pH on suppression of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici by Pseudomonas fluorescens 2-79. Phytopathology 1992, 82, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Hendson, M.; Panopoulos, N.J.; Schroth, M.N. Cloning of a phenazine biosynthetic locus of Pseudomonas aureofaciens PGS12 and analysis of tis expression in vitro with the ice nucleation reporter gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 2931–2938. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, B.K.; Defago, G. Environmental factors modulating antibiotic and siderophores biosynthesis by Pseudomonas flourescens biocontrol strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2429–2438. [Google Scholar]

- Cretoiu, M.S.; Korthals, G.; Visser, J.; van Elsas, J.D. Chitin amendment raises the suppressiveness of soil towards plant pathogens and modulates the actinobacterial and oxalobacteriaceal communities in an experimental agricultural field. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 28, 01361. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Public Health, Occupational Health Branch, Preventing Work-Related Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis). 2018. Available online: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DEODC/OHB/Pages/Cocci.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Wall, D.H.; Nielsen, U.N.; Six, J. Soil biodiversity and human health. Nature 2015, 528, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajsa, N.; Morel, M.A.; Braña, V.; Castro-Sowinski, S. The effect of agricultural practices on resident soil microbial communities: Focus on biocontrol and biofertilization. Mol. Microb. Ecol. Rhizosphere 2013, 2, 687–700. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, C.; Lucas, K.D.; Mohle-Boetani, J.C. Rates and Risk Factors for Coccidioidomycosis among Prison Inmates, California, USA, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Medeiros Muniz, M.; Pizzini, C.V.; Peralta, J.M.; Reiss, E.; Zancopé-Olivera, R.M. Genetic diversity of Histoplasma capsulatum strains isolated from soil, animals, and clinical specimens in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, by a PCR-based Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 4487–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, J.W.; Schwan, W.R.; Volk, T.J. PCR-based detection of DNA from the human pathogen Blastomyces dermatidis in natural soil samples. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Sites | Reference Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site A (Cole’s Levee Rd.) | Site B (across CALM) | Sharktooth Hill | |

| Soil Parameters | |||

| coordinates | 119° 13″ 60.0′ W, 35° 14″ 08.0′ N | 118°513″ 14.1′ W 35° 25″ 50.3′ N | 118° 54″ 37.0′ W, 35° 28″ 20.0′ N |

| vegetation | grasses and herbs (native and non-native) | grasses and herbs (native and non-native) | grasses and herbs (native and non-native) |

| soil type | Garces loam | Chanac clay loam | Pleito-Trigo-Chanac complex |

| landform | fan remnants | fan remnants | fan remnants/stream terraces |

| parent material | alluvium derived from granitoid | alluvium derived from mixed | alluvium derived from mixed |

| (soil map unit symbols) | 180 | 130 | 205 |

| drainage class | well drained | well drained | well drained |

| maximum salinity (mmhos/cm) | 8–16 | 0–2 | 0–2 |

| Physical Parameters | |||

| Surface texture | clay loam | clay loam | gravelly clay loam |

| Clay (%) | 25.5 | 31 | 33.5 |

| Silt (%) | 36.5 | 33.6 | 36.5 |

| Sand (%) | 38 | 35.4 | 30 |

| Available water capacity (cm/cm) | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Available water supply (0-25 cm) | 5.04 | 4.25 | 3.69 |

| Organic matter (%) | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1.5 |

| Water content (15 bar) | 16.7 | 18.2 | 17.2 |

| Water content (1/3 bar) | 30.9 | 30.1 | 29.3 |

| Sat. hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) (micrometers/s) | 8.37 | 9 | 2.82 |

| Chemical Parameters | |||

| pH | 8.5 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| CaCO3 (%) | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Cation exchange capacity (CEC7) (milliequivalents/100 grams) | 20.6 | 24.4 | 24.3 |

| Gypsum (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Electrical conductivity (decisiemens/m) | 5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Isolate # | Fungal ID | GenBank Accession # or ATCC # | Similarity (%) | Challenge Assays: Bacteria against Fungi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Firmicutes | ||||||||||

| IV-4 | IV-7 | IV-18 | BA-3 | T-4b | IV-1A | BA-35 | BA-36 | ||||

| KVF4 | Alternaria alternata | AY154682 | 96 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| LDF1 | Aspergillus versicolor | KJ082097 | 99 | neg | neg | pos | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos |

| LDF2 | Aspergillus keveii | MF004311 | 98 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| ZMF2 | Lewia infectoria | AY154691 | 98 | neg | pos | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| AKF4 | Aspergillus keveii | MF004311 | 98 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| AKFB | Penicillium citrinum | KM491892 | 99 | neg | pos | neg | neg | neg | pos | neg | pos |

| 482-2 | Penicillium gladioli | DQ339568 | 92 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos |

| 426-1 | Penicillium gladioli | DQ339568 | 92 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| 435-2 | Penicillium gladioli | DQ339568 | 92 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| N26-6 | Peniophora sp. | HQ608067 | 98 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| ZMF-1 | Fusarium proliferatum | LT841264 | 97 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| AKF7 | Fusarium accuminatum | KJ019024 | 98 | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| U. reesii | Uncinocarpus reesii | ATCC34534 | 100 | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos |

| C. immitis | Coccidioides immitis | MH863096 | 99 | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos | pos |

| Isolate ID | Colony Morphology on R2A+SE | Closest Match in GenBank with Similarity (%) and Accession # | R2A+SE, Incubated at Different Temperatures | R2A+SE, Supplemented with Salt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 °C | 50 °C | 63 °C | Borate (0.5%) | NaCl (10%) | NaCl (20%) | |||

| BA-35 | large, white-tan, dull, flat, irregular margin | Bacillus subtilis, 99%, CP024961 | pos | pos | neg | neg | pos | neg |

| BA-36 | large, white-tan, dull, flat, irregular margin | Bacillus subtilis, 99%, CP024961 | pos | pos | neg | neg | pos | neg |

| IV-1A | large, white-tan, dull, flat, irregular margin | Bacillus subtilis, 99%, CP024961 | pos | pos | few colonies | neg | pos | neg |

| V-2 | medium size, grey | Streptomyces cavourensis, 98 %, CP030930 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| T-3 | large size, white | Streptomyces cavourensis, 97 %, CP030930 / Streptomyces bacillaris, 98%, CP029379 | pos | neg | neg | pos | neg | neg |

| IV-10a | large size, white | Streptomyces halotolerans, 97%, AY376199 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| IV-7 | medium size, purple | Streptomyces lavendulae, 99%, KY213666 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| IV-12 | medium size, white | Streptomyces fulvissimus, 99%, KY820718 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| T-4b | large size, white | Streptomyces halotolerans, 97%, AY376199 | pos | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| V-5 | small size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 97%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| IV-4 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 97%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | few colonies | pos | neg |

| IV-18 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 98%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| IV-21 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 99%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | few colonies | pos | neg |

| IV-19 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 99%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| BA-3 | small size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 98%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| BA-5 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 99%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| BA-23 | medium size, white | Streptomyces sparsus, 99%, KM999546 | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | neg |

| Y-2 | medium size, purple | Streptomyces flavofungini, 94%, JQ511979 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| Col.B | small size, white | Streptomyces bobili, 99%, FJ792573 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| T-2 | large size, white | Nocardiopsis synnemataformans, 99%, MH040869 | pos | neg | neg | pos | neg | neg |

| T-4a | tiny size, white | Pseudonocardia autotrophica, 99%, AP018920 | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lauer, A.; Baal, J.D.; Mendes, S.D.; Casimiro, K.N.; Passaglia, A.K.; Valenzuela, A.H.; Guibert, G. Valley Fever on the Rise—Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7020031

Lauer A, Baal JD, Mendes SD, Casimiro KN, Passaglia AK, Valenzuela AH, Guibert G. Valley Fever on the Rise—Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Microorganisms. 2019; 7(2):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7020031

Chicago/Turabian StyleLauer, Antje, Joe Darryl Baal, Susan D. Mendes, Kayla Nicole Casimiro, Alyce Kayes Passaglia, Alex Humberto Valenzuela, and Gerry Guibert. 2019. "Valley Fever on the Rise—Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis" Microorganisms 7, no. 2: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7020031

APA StyleLauer, A., Baal, J. D., Mendes, S. D., Casimiro, K. N., Passaglia, A. K., Valenzuela, A. H., & Guibert, G. (2019). Valley Fever on the Rise—Searching for Microbial Antagonists to the Fungal Pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Microorganisms, 7(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7020031