Abstract

One of the main public health problems nowadays is the increase of antimicrobial resistance, both in the hospital environment and outside it (animal environment, food and aquatic ecosystems, among others). It is necessary to investigate the virulence-associated factors and the ability of horizontal gene transfer among bacteria for a better understanding of the pathogenicity and the mechanisms of dissemination of resistant bacteria. Therefore, the objective of this work was to detect several virulence factors genes (fimA, papC, papG III, cnf1, hlyA and aer) and to determine the conjugative capacity in a wide collection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases-producing E. coli isolated from different sources (human, food, farms, rivers, and wastewater treatment plants). Regarding virulence genes, fimA, papC, and aer were distributed throughout all the studied environments, papG III was mostly related to clinical strains and wastewater is a route of dissemination for cnf1 and hlyA. Strains isolated from aquatic environments showed an average conjugation frequencies of 1.15 × 10−1 ± 5 × 10−1, being significantly higher than those observed in strains isolated from farms and food (p < 0.05), with frequencies of 1.53 × 10−4 ± 2.85 × 10−4 and 9.61 × 10−4 ± 1.96 × 10−3, respectively. The reported data suggest the importance that the aquatic environment (especially WWTPs) acquires for the exchange of genes and the dispersion of resistance. Therefore, specific surveillance programs of AMR indicators in wastewaters from animal or human origin are needed, in order to apply sanitation measures to reduce the burden of resistant bacteria arriving to risky environments as WWTPs.

1. Introduction

E. coli is one of the main causative agents of gastrointestinal and extra intestinal infections. This ubiquitous organism is a major element of the normal commensal microbiota in the human and animal intestinal tract and it has been found in soil, food, water, and vegetation [1]. The ability of E. coli to cause a variety of infectious diseases, such as sepsis, pneumonia, or urinary tract infections, is associated with the expression of specific virulence factors (VFs). In addition, the multidrug resistance profile of E. coli strains increases the risk of antimicrobial treatment failure in both humans and animals [2].

Resistance to antibiotics can occur by different processes, like the acquisitions of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) via horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Several genetic mechanisms have been involved in the spread of ARGs, but conjugation is thought to have the greatest influence [3]. Furthermore, it has been reported that E. coli obtains antimicrobial resistance faster than other microorganisms [4]. It is especially relevant regarding the increase of β-lactam resistance in E. coli due to the production of extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL). Mobile Genetics Elements (MGSs) are able to spread ESBL associated genes by horizontal transfer to others Gram-negative bacteria [5].

Likewise, it is believed that the acquisition of several virulence factors via horizontal gene transfer provides an evolutionary pathway to pathogenicity [6]. VFs are important at the initial stages of infection (when the bacteria have to adapt to the host environment) and include adhesins (FimA, PapC, and PapG allele III), toxins (HlyA and Cnf1), and other proteins like siderophores (Aer) [7]. In the case of adherent structures, fimA encodes the major structural subunit of type 1 fimbriae and it is present in almost all E. coli strains and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family [8]. However, papC and papG encode adhesin molecules that are found in P fimbriae and are especially linked to uropathogenic strains [9]. Regarding toxins, cnf1 encodes for cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, a toxin secreted by some virulent strains associated with neonatal meningitis and urinary infections [10]. On the other hand, HlyA (cytotoxin hemolysin A or α hemolysin) is expressed with larger severity in infections caused by uropathogenic strains with a higher prevalence of kidney damage and bacteremia [11].

Previous studies performed by our research group [12,13,14,15,16] have provided us with a great collection of multidrug resistant ESBL-producing E. coli strains isolated from human, animal, food and water environments in Navarra (Spain). The objective of the present study was to (i) determine the virulence gene profiles and (ii) to determine the ability of horizontal gene transfer in a selection of ESBL-producing E. coli strains in order to a achieve a better understanding of the antibiotic resistance dissemination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Collection

From our own collection of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated in Navarra (Spain) from different sources, a total of 150 E. coli strains were selected for the study: human origin (including healthy volunteers (n = 13) and clinical cases (n = 36)), food products (n = 48), farms and feed (n = 20), and rivers and wastewater treatment plants [WWTPs] (n = 33). Having taken into account the available data from previous characterization [14,16,17], the following criteria were considered for the selection of strains: to show a multidrug resistant pattern (MDR), to carry different types of β-lactamase genes and belonging to different phylogenetic groups according to Clermont et al. [18] or different sequence types (including the ST131) following the scheme described by Wirth et al. [19]. Complete information of each strain (including the virulence genes and conjugation frequencies determined in this work) is presented in the Supplemental Material (Figures S1–S5).

2.2. Virulence Factor Gen Detection and Sequence Analysis

DNA extraction of the selected strains was performed with DNeasy® Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Barcelona, Spain), using a pre-treatment protocol for Gram-negative bacteria and following the manufacturer’s instruction. The quantity and quality of DNA was analyzed using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

E. coli DNA extracts were tested by conventional PCR using the specific primers and conditions showed in Table 1, for the presence of VF genes that mediate adhesion (fimbrial adhesion genes, fimA, papC, and papG allele III), toxins (α-haemolysin hlyA and cytotoxic necrotizing factor cnf1) and siderophores (aer) [20,21].

Table 1.

Primers and conditions used for the amplification of virulence factors genes.

Amplicons obtained were sequenced by the Macrogen EZ-Seq purification service (Macrogen Europe, Madrid, Spain) to confirm the presence of VF genes. Searches for DNA and protein homologies were carried out using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), using the BLAST program. Alignment of DNA and amino acids sequences was performed using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/).

2.3. Conjugation Assay

Conjugative transfer of ESBL genes among selected E. coli strains was studied using the mixed broth method [22]. E. coli DSM 9036 was used as a recipient strain. This strain is plasmid-free, streptomycin-resistant, and sensitive to β-lactams antibiotics (F-, thr-1, ara-14, leuB6, Delta(gpt-proA)62, lacy,1 tsx-33, qsr-, supE44, galK2, lambda- rac-, hisG4(Oc), rfbD1, mgl-51, rpsL31, kdgK51, xyl-5, mtl-1, argE3(Oc), thi-1). In the case of donor strains, as most of the E. coli-ESBL isolates were MDR, we selected as donor strains only those streptomycin sensitive (n = 70).

The donor and recipient strains were grown in BHI (Scharlab, Barcelona, Spain) at a concentration of approximately 1.0 × 109 CFU/mL (overnight cultures, 37 °C). Equal volumes (5 mL) of cultures of the donor and the recipient strains were mixed (1:1) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Transconjugants were selected on TSA agar (Scharlab) supplemented with streptomycin (100 µg/mL) and ampicillin (30 µg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain), to inhibit the growth of recipient and donors strains, respectively. After the incubation period (24 h at 37 °C), the number of colonies (CFU) was counted. Conjugation frequencies were expressed as the number of CFU of transconjugants relative to the number of CFU of donors. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The molecular characterization of the transconjugants was performed by PCR amplification of the genes involved in the resistances (blaCTX-M and blaTEM) [23,24].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The results were subjected to statistical processing with the SPSS 15 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), applying the Chi-square (X2) and ANOVA test with a level of significance of p < 0.05.

BioNumerics, version 7.6 (Applied Maths NV/bioMérieux, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) was used to create the Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) graphs. They were generated based on a distance matrix calculated by the Pearson correlation and unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) functions.

2.5. Informed Consent and Ethical Statement

Informed consent was obtained in all cases prior to collecting the samples (from parents in the case of participating children), using a template approved by the Ethical Committee Research of the University of Navarra (27 Jul 2018) [15].

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Virulence Factors Genes

Overall, all the isolates tested were positive for one or more VF genes (Figures S1–S5). In fact, the co-occurrence of several VFs in the same strain was frequent and most of the isolates contained two or three virulence genes (40.7% and 36%, respectively). Among the 150 tested strains, the genes encoding FimA (97.3%), Aer (72%) and PapC (60%) were the most commonly found and were detected in all studied environments (Table 2). Regarding fimA, the presence in farms and feed was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than that found in clinical cases and food products. Furthermore, the expression of aer in clinical samples was significantly higher than in rivers and WWTPs, food products, and healthy volunteers’ isolates. In contrast, the prevalence of papC was significantly different between all environments (p < 0.05) except for clinical, farms and feed and healthy volunteers’ samples.

Table 2.

Prevalence of virulence-associated genes among extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli from different sources.

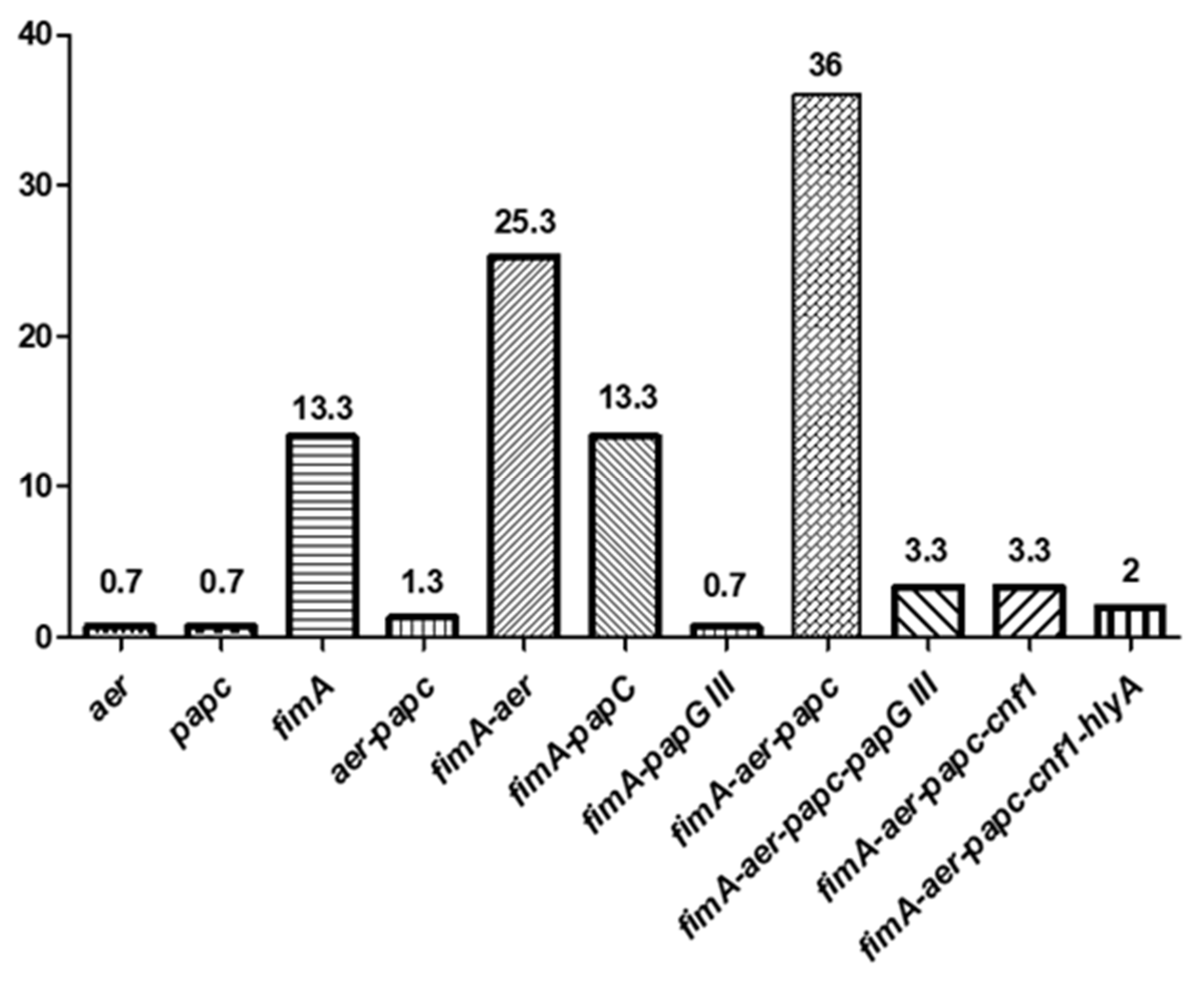

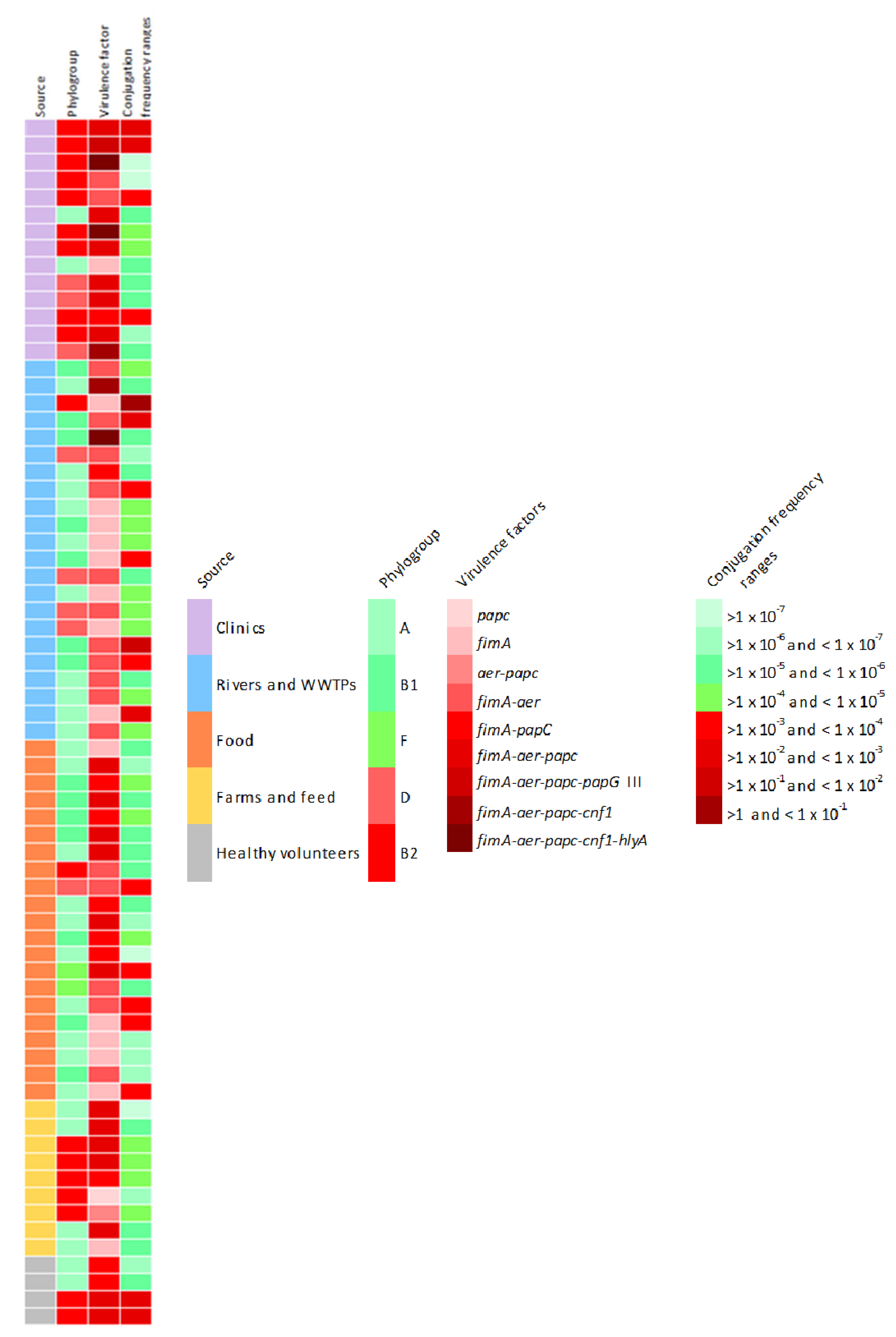

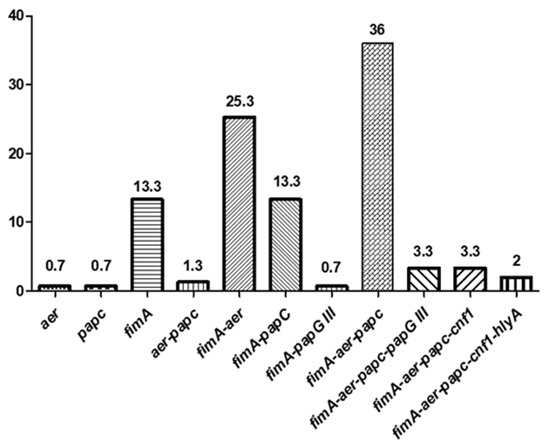

It is remarkable that the unique source in which all types of VF genes were detected were the clinical samples. In addition, those strains contain a greater number of virulence factors compared to those from the rest of the environments, but none of the isolates carried all the 6 studied genes. The three strains containing the hlyA gene (2%) were the only ones that presented 5 virulence factors (positive for fimA, aer, papC, cnf1, and hlyA). Likewise, the co-occurrence of fimA-aer-papC and fimA-aer was the most frequently reported (36% and 25.3%, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The co-occurrence (percentages) of several virulence factors (VFs) in ESBL-producing E. coli.

3.2. Distribution of Virulence Genes among the Phylogenetic Groups

All the virulence genes were present among phylogroups B2 and B1 and most of them were detected in phylogenetic groups A and D (Table 3). It must be pointed out that gene toxins were found almost exclusively in A, B1, B2, and D groups. Adhesin PapC and toxin HlyA were more prevalent in group B2 as compared to the group D, in which the highest prevalence of toxin gene cnf1 was found.

Table 3.

Distribution of virulence genes among phylogenetic groups of ESBL-producing E. coli.

From the total of strains showing the ST131 (n = 16; all of them isolated from clinical cases and healthy volunteers), the vast majority (68.8%) were positive to aer, papC, and fimA (Figures S1 and S5). Furthermore, one clinical isolate ST131 was positive for 5 out of the 6 VF (fimA, aer, papC, cnf1 and hlyA).

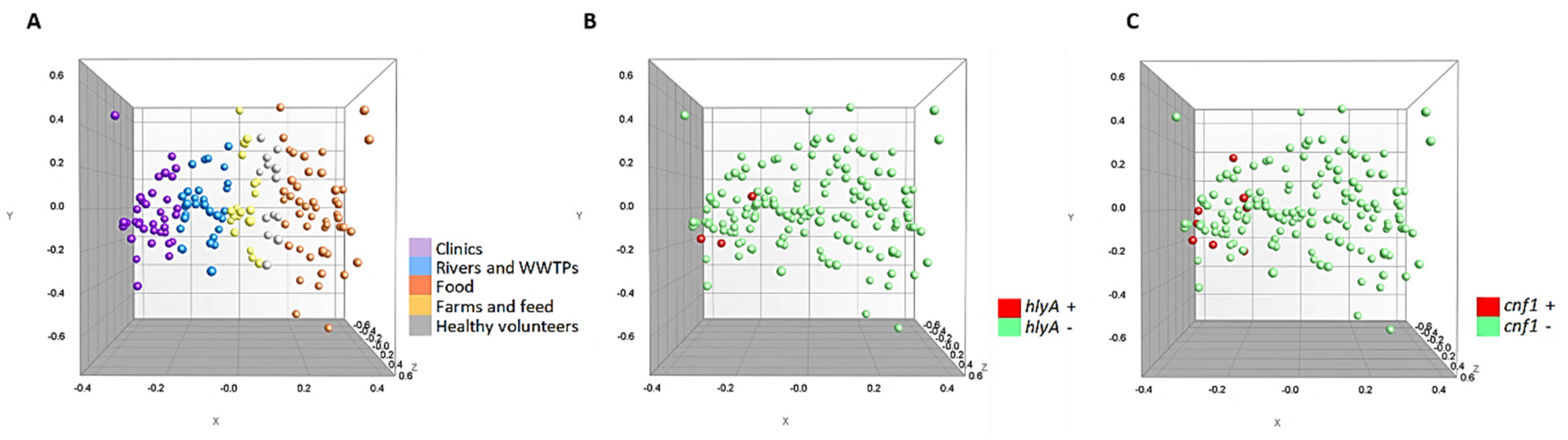

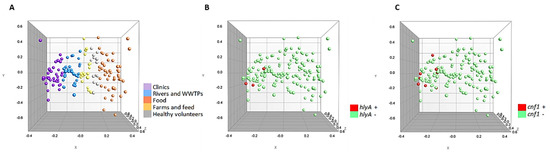

Additionally, the multidimensional scaling graphs (MDS) showed in Figure 2 demonstrate that the 150 strains were homogeneously grouped according to the source of isolation (Figure 2A). Likewise, it can be seen that the hlyA and cnf1 positive strains (Figure 2B,C) are strongly related, being very close in the variable space (X, Y and Z axis).

Figure 2.

Multidimensional scaling graphs (MDS) for the 150 strains. (A) According to origin; (B) hlyA positive and negative strains (C) cnf1 positive and negative strains.

3.3. Horizontal Transfer of ESBL Genes

The 100% of the tested ESBL-producing E. coli strains (n = 70) were able to perform an efficient gene transfer, making the recipient strain (E. coli DSM 9036) resistant to ampicillin. Although the range of conjugation rates is nearly the same in samples from all origins, it was observed that strains isolated from aquatic environments showed significantly higher conjugation frequency values (p < 0.05), with an average value of 1.15 × 10−1 ± 5 × 10−1 (Table 4). In fact, the highest value was observed in a strain coming from a WWTP (2.35 ± 8.51 × 10−2), which confirms the potential risk of dissemination of ARG through these environments. On the other hand, the isolates from farms and feed and food products showed lower frequencies, with an average value of 1.53 × 10−4 ± 2.85 × 10−4 and 9.61 × 10−4 ± 1.96 × 10−3, respectively.

Table 4.

Conjugation frequencies of ESBL-producing E. coli according to their origin.

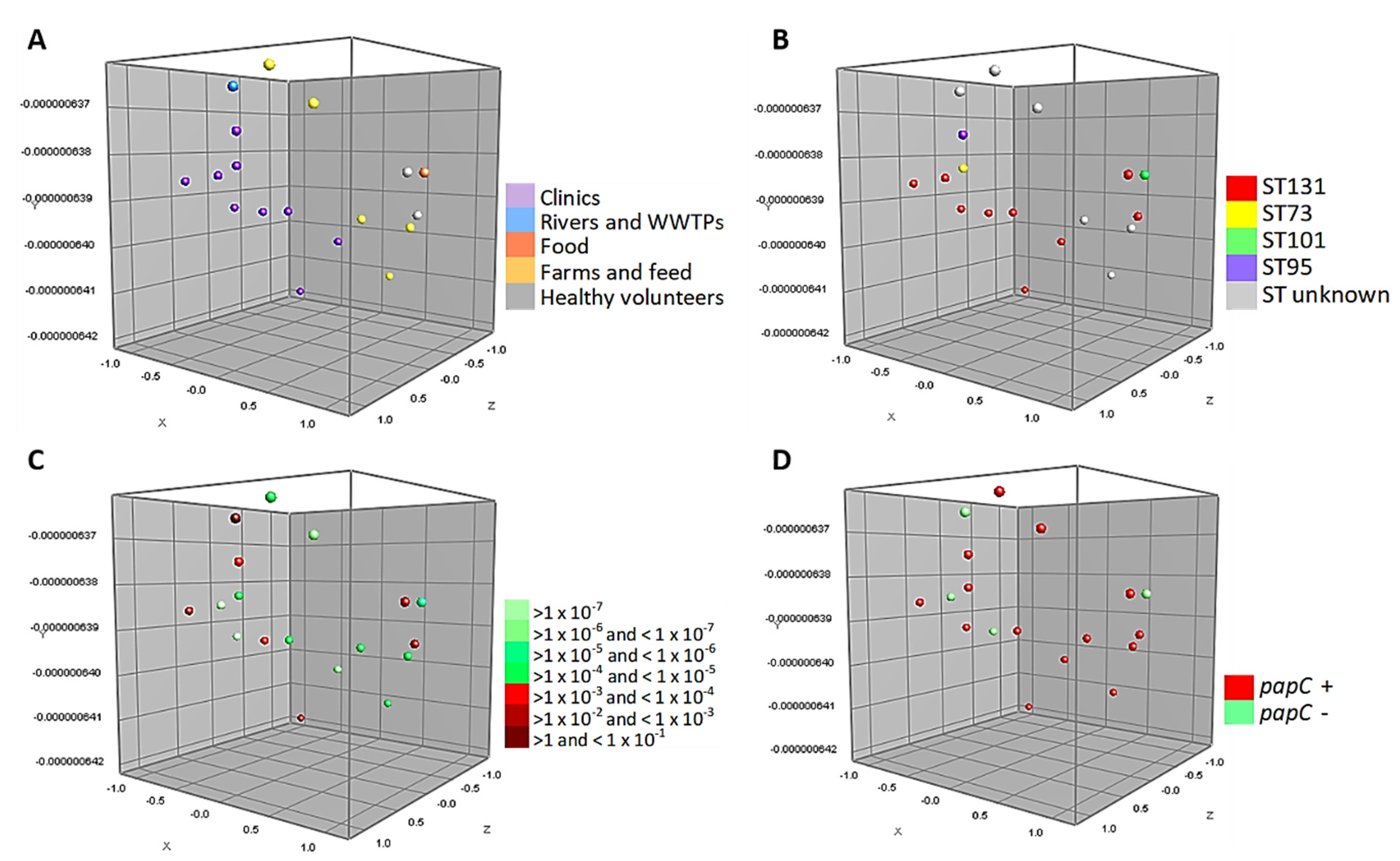

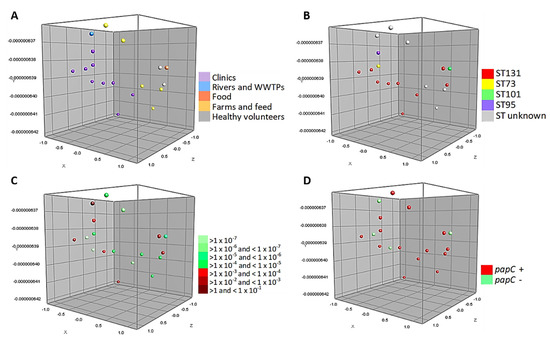

Figure 3 shows the MDS of the 18 strains tested in the conjugation assays belonging to phylogroup B2 (associated with more virulent strains). These strains are closely associated, grouping homogeneously according to the source of isolation. Likewise, half of the isolates belong to ST131 and 39% of them are capable of performing a conjugation with a frequency range between >1 and < 1 × 10−4. In particular, it can be seen that 1 WWTPs isolate and 6 strains of human origin (clinical cases and healthy volunteers) have a high conjugation frequency. In addition, Figure 3D shows the relationship of the virulence factor papC with this phylogroup.

Figure 3.

Multidimensional scaling graphs (MDS) for the 18 isolates B2, tested in the conjugation assays; (A) According to the distribution by origins; (B) MLST types; (C) Conjugation frequency ranges of these strains, and (D) Prevalence of papC genes.

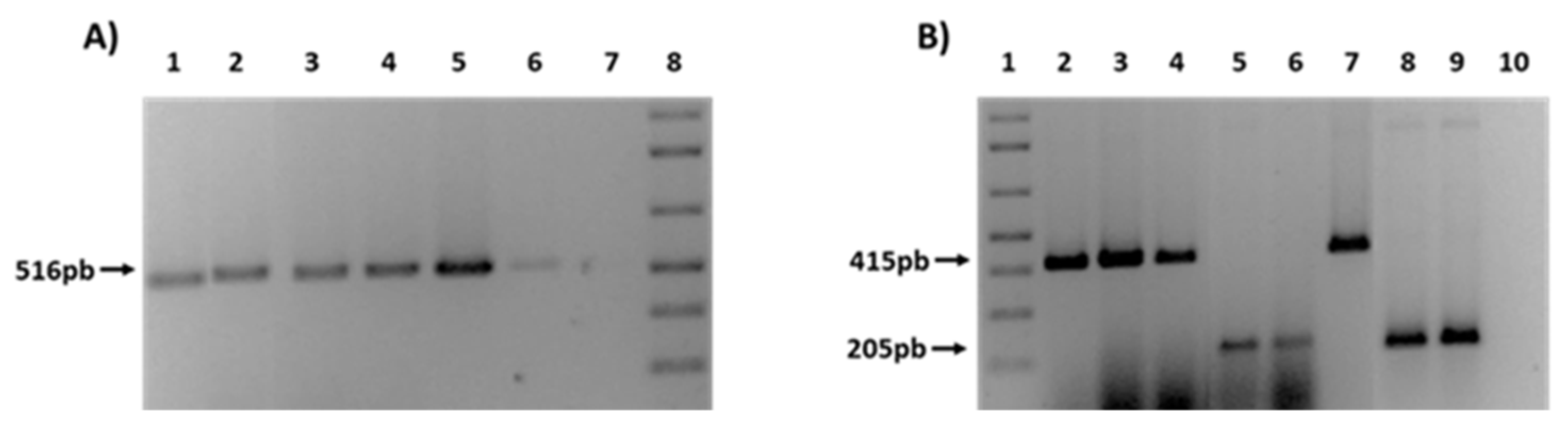

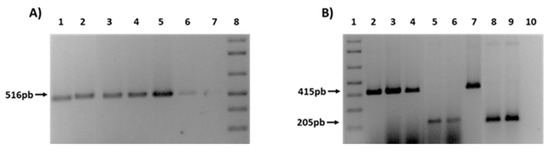

Finally, in order to confirm the transfer of ESBL genes, different PCRs were performed for the detection of blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes in the transconjugants (Figure 4). As an example, Figure 4A shows the presence of TEM-1 gene in 4 transconjugants obtained from farm (F) and rivers (R) strain donors (1F, 2F, 3F, 1R). In a similar way, Figure 4B shows 5 transconjugants also from rivers (R) and WWTPs (W) (2R, 1W, 2W), that had acquired the type of CTX-M present in the donor strain (CTX-M1 or CTX-M9).

Figure 4.

PCRs for the ESBL genes detection in transconjugants. (A) Presence of TEM-1 gene. 1: 1F; 2: 2F; 3: 3F; 4: 1R. 5-6: C + TEM-1; 7: C−; 8: 1Kb plus ladder. (B) Presence of CTX-M 1 and CTX-M9. 1: Kb plus ladder; 2: 1F; 3: 2F; 4: 2R; 5: 1W; 6: 2W. 7: C + CTX-M1; 8-9: C + CTX-M9; 10: C−.

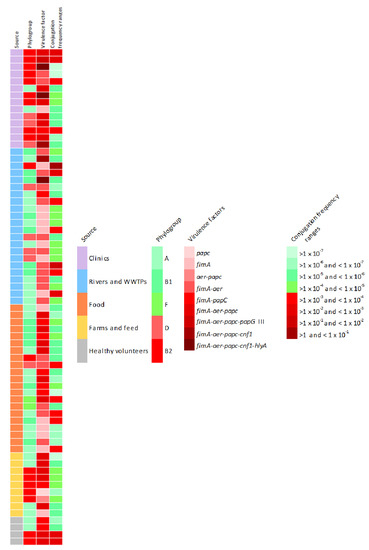

To sum up all the findings, Figure 5 shows the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the 70 isolates tested in the conjugation assays. Red colored boxes indicate the riskiest condition, according to the legend.

Figure 5.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the 70 isolates tested in the conjugation assays. Red coloured boxes indicate the riskiest condition, according to the legend.

As we can see, although the highest conjugation frequency average have been observed in strains isolated from aquatic environments (1.15 × 10−1 ± 5 × 10−1), these strains only have one or two virulence factors, so clinical isolates contain the greatest amount of virulence factors studied and are related with the most pathogenic phylogroups. It must be taken into account that five strains isolated from clinical samples and healthy volunteers have been characterized as potentially pathogenic, since all of them belong to the ST131-B2 phylogroup, contain between 3 and 5 virulence factors and most of them have high conjugation rates.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to characterize the virulence and conjugative capacity of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from human, food products, farm origin, and water environments, for a better understanding of the risk of dissemination of these resistant bacteria.

As expected, clinical isolates showed the highest prevalence of the studied virulence factor genes (encoding adhesins, siderophores, and toxins), in accordance with the main observed phylogroups in this origin (B1, B2 and D), which have been associated with more virulent strains (Figure 5). However, it must be noticed the presence of several VFs in strains isolated from aquatic environments, which could be related with the higher conjugation frequencies observed in those strains. Furthermore, it is remarkable that the majority of human strains showing the ST131 carried 3 or more VF genes, differing to Alonso et al. [25] who determined an apparent absence of classical virulence factors such as papC, cnf1 and hlyA. In addition, the unique strain of the present study in which the co-occurrence of 5 VF genes was observed (fimA, aer, papC, cnf1 and hlyA) was a clinical isolate ST131. Thus, the pathogenicity of ST131 E. coli isolates (causing infections in both community and hospital) has been associated to the large number of virulence-associated genes they contain [26].

Regarding adhesins, fimbriae have a fundamental role in the colonization (type I) and pathogenicity (type P) of extraintestinal infections caused by E. coli (such as urinary infections). Concerning fimA, the high prevalence observed (97.3%) suggests that type I fimbriae are widely distributed. Despite the fact that their presence is not limited to pathogenic strains [25], the expression of these fimbriae improves the virulence of uropathogenic E. coli [27]. Similarly, P fimbriae contribute to the virulence of uropathogenic strains by promoting bacterial colonization tissues and stimulating a host inflammatory response [28,29]. In the present study, we examined the genes associated with the outer membrane protein (papC) and papG III allele adhesin. The first one has been detected in all the studied environments, with a lower prevalence in aquatic environments (rivers and WWTPs, 15.2%). In contrast, papG III genes have been detected mainly in clinical strains, in accordance with the reported presence of this virulence factor in E. coli strains causing pyelonephritis or cystitis [30,31]. It has also been detected in two strains isolated from chicken and beef belonging to phylogroup D and carrying intI1 and blaCTX-M14. These results support the potential transmission of pathogenic E. coli through foods, having into account that an effective cell adhesion followed by invasion are the key events in pathogenicity [32]. In summary, type 1 fimbriae and P fimbriae can co-exist in the same microorganism, since the 6 positive strains for papG III also contain fimA. The reported association between papG III gene and genes encoding α-hemolysin (hlyA) and the cytotoxic necrotizing factor (cnf1) [28] has not been detected in this study.

With respect to siderophores, the aer gene has been detected in all environments but with higher prevalence in clinical isolates (91.6%). This gene encodes a bacterial iron chelating agent that allows E. coli to obtain iron from iron-poor environments such as the urinary tract [33]. The observed prevalence in average (72%) is similar to that reported by Raeispour and Ranjbar [34], but higher than that observed by Jalali et al. [35]. Some works indicate that there is a large variation in the aer frequencies, because the prevalence of this gene vary with phylogenetic groups, localization and clinical conditions [36]. Furthermore, Arisoy et al. [37] point out that aer might be one of the main contributors to the persistence of E. coli in the intestinal flora and Searle et al. [38] indicate that environmental E. coli isolates contain less genes associated with aerobactin. On the other hand, the clonal complexes ST155 linked with the phylogroup B1 is frequently associated with resistance and even with the ESBL phenotype in E. coli from human, animal and environmental sources. So, regarding our results and according with Alonso et al. [25], the virulence-associated factors genes of this ST was mainly fimA and aer.

Genes hlyA and cnf1 encode toxins that can participate in the rupture of the epithelial barrier, allowing bacteria to pass from the digestive tract into the bloodstream and colonize different tissues, such as the urinary tract [39]. Hence, these factors are related to extraintestinal infections, mainly with uropathogenic strains and enterohemorrhagic E. coli that can cause diarrheal and haemolytic uremic syndrome [11]. In accordance with these observations, 5 clinical isolates coming from urine samples contain the cnf1 gene. In addition, in 3 of them hlyA and cnf1 genes coexist, coinciding with the observations of both genes in the same pathogenicity island [21]. In contrast to that published by Johnson et al. [40], the observed prevalence of cnf1 in the present study is higher than hlyA (5.3% and 2%, respectively). It must be mentioned the prevalent presence of these virulence factors in clinical isolates, according with Cortés et al. [41]. However, these two factors have also been detected in 3 isolates from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). This would pose an especial risk, since these sources are considered to be the hotspots for the environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) [3]. Since cell adhesion, invasion, and the presence of toxins are the key events in pathogenicity, we can point out that the strains especially pathogenic are the 3 positives for hlyA gene, isolated from clinical samples and WWTP (Figure 5). However, it would be interesting to study whether these genetic profiles correspond to virulent phenotypes performing biofilm formation, adhesion and invasion assays.

Although WWTPs are designed to reduce the contamination and organic material of water, the presence of resistant bacteria in the effluents has been reported [13,42]. In fact, the environmental conditions in these plants favor the proliferation of ARB, the dispersion of ARG and the production of strong biofilm that increases the capacity to colonize the sewer system [43,44]. High conjugation rates have been reported in bacterial biofilms [45], which together with the observed conjugation frequencies in aquatic strains, poses WWTPs as risky environments for the transmission of AMR. As indicated by WHO [46], the appropriate management and treatment of sewage is an essential action for the prevention of the spread of different human diseases. Therefore, the first step to combat environmental dissemination routes of AMR is to ensure that at least basic sanitation needs are met.

However, scientific knowledge has not yet progressed to establish the objectives for estimating the risks of ARB and ARG abundance in wastewater. Assessing the different risks to which human populations may be exposed and determining pollutants concentrations should be one of the main objectives [47]. Nonetheless, it is difficult to imagine a risk assessment framework that includes all complex gene transfer events, which may take place from environmental bacteria to human or animal pathogens [48].

Resistance monitoring data in humans and farm animals in several regions should be used to provide necessary information and to select the specific gen markers under study. For that, it would be valuable to determine whether simple indicators represent a broadly risk. According to Gillings et al. [49] the integrase class 1 intI1 could be used as a promising indicator for anthropogenic ARG contamination, because they have a high clinical relevance. In fact, the 92% of the strains tested in this study carried the aforementioned gene intI1 (Figures S1–S5). Another thing that would be valuable to measure is the rates at which the horizontal gene transfer occurs in the WWTPs. However, this is still an important knowledge gap [47]. In this sense, it has been reported that conjugation is an extremely effective mechanism for dissemination of ESBLs [50]. Our data reinforce the hypothesis of ARG dissemination in aquatic environments through this mechanism, because higher conjugation frequencies have been observed in strains isolated from these environments, especially from WWTPs. In addition, conjugation experiments showed that these genes are probably located in the same transferable plasmid. In fact, the 4 strains with higher conjugation frequencies, contain the integrase class 1 intI1 gene and different insertion sequences (ISEcp1, IS26, IS903) (Figures S1–S5). Nevertheless, very little is known about the health risks posed by exposure to commensal or environmental bacteria that carry mobile ARGs [47]. The conjugation process may occur in many types of ecosystems, but in food environments can have very serious consequences, due to the mobilization of virulence genes and toxins [51]. As good news, our results indicate that the average conjugation frequencies in bacteria isolated from food products was not very high (9.61 × 10−4 ± 1.96 × 10−3). The food chain is one of the main routes for the introduction of resistant bacteria into the gastrointestinal tract, where genes can be transferred between pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria (as shown from our data from healthy volunteers).

In conclusion, this study has provided information on genotypes related to resistance, virulence and conjugation capacity of ESBL-producing E. coli isolated from different environments. The obtained results point out the important role of the aquatic environment for virulence gene exchange and resistance dissemination. Therefore, it would be necessary to control the presence of multidrug resistant bacteria (o superbug) in risky environments such as wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) to ensure the effectiveness of antibiotics for public health.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/4/568/s1. Figure S1. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates from clinical cases (n = 36), Figure S2. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates from healthy volunteers (n = 13), Figure S3. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates from aquatic environments (n = 33), Figure S4. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates from food (n = 48), Figure S5. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates of farm origin (n = 20).

Author Contributions

L.P.-E. performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. D.G. and A.I.V. conceived, designed the experiments, supervised data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant of “la Caixa” Banking Foundation and the “Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kaczmarek, A.; Skowron, K.; Budzyńska, A.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Virulence-associated genes and antibiotic susceptibility among vaginal and rectal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy pregnant women in Poland. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2018, 63, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogg, A.L.; Zurfluh, K.; Schmitt, S.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Stephan, R. Antimicrobial resistance, multilocus sequence types and virulence profiles of ESBL producing and non-ESBL producing uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from cats and dogs in Switzerland. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 216, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Wintersdorff, C.J.H.; Penders, J.; Van Niekerk, J.M.; Mills, N.D.; Majumder, S.; Van Alphen, L.B.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; Wolffs, P.F.G. Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Yahia, H.; Ben Sallem, R.; Tayh, G.; Klibi, N.; Ben Amor, I.; Gharsa, H.; Boudabbous, A.; Ben Slama, K. Detection of CTX-M-15 harboring Escherichia coli isolated from wild birds in Tunisia. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Moon, J.S.; Oh, D.H.; Chon, J.W.; Song, B.R.; Lim, J.S.; Heo, E.J.; Park, H.J.; Wee, S.H.; Sung, K. Genotypic characterization of ESBL-producing E. coli from imported meat in South Korea. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, T.A.; Wu, X.Y.; Barchia, I.; Bettelheim, K.A.; Driesen, S.; Trott, D.; Wilson, M.; Chin, J.J.C. Comparison of virulence gene profiles of Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy and diarrheic swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4782–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthje, P.; Brauner, A. Virulence Factors of Uropathogenic E. coli and Their Interaction with the Host. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2014, 65, 337–372. [Google Scholar]

- Farfán-García, A.E.; Ariza-Rojas, S.C.; Vargas-Cárdenas, F.A.; Vargas-Remolina, L.V. Mecanismos de virulencia de Escherichia coli enteropatógena. Rev. Chil. Infectología 2016, 33, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, N.; Wold, A.E.; Adlerberth, I. Antibiotic resistance is linked to carriage of papC and iutA virulence genes and phylogenetic group D background in commensal and uropathogenic Escherichia coli from infants and young children. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, A.; Travaglione, S.; Fiorentini, C. Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1): Toxin biology, in Vivo applications and therapeutic potential. Toxins (Basel) 2010, 2, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielaszewska, M.; Aldick, T.; Bauwens, A.; Karch, H. Hemolysin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: Structure, transport, biological activity and putative role in virulence. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 304, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojer-Usoz, E.; González, D.; Vitas, A.I.; Leiva, J.; García-Jalón, I.; Febles-Casquero, A.; de la Soledad Escolano, M. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in meat products sold in Navarra, Spain. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojer-Usoz, E.; González, D.; García-Jalón, I.; Vitas, A.I. High dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae ineffluents from wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2014, 56, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitas, A.I.; Naik, D.; Pérez-Etayo, L.; González, D. Increased exposure to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae through the consumption of chicken and sushi products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 269, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Gallagher, E.; Zúñiga, T.; Leiva, J.; Vitas, A.I. Prevalence and characterization of β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in healthy human carriers. Int. Microbiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Etayo, L.; Berzosa, M.; González, D.; Vitas, A.I. Prevalence of integrons and insertion sequences in ESBL-producing E. coli isolated from different sources in Navarra, Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojer-Usoz, E.; González, D.; Vitas, A.I. Clonal diversity of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from environmental, human and food samples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clermont, O.; Christenson, J.K.; Denamur, E.; Gordon, D.M. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: Improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Falush, D.; Lan, R.; Colles, F.; Mensa, P.; Wieler, L.H.; Karch, H.; Reeves, P.R.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Ochman, H.; et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: An evolutionary perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 1136–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Terai, A.; Yuri, K.; Kurazono, H.; Takeda, Y.; Yoshida, O. Detection of urovirulence factors in Escherichia coli by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1995, 12, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Simon, K.; Horcajada, J.P.; Velasco, M.; Barranco, M.; Roig, G.; Moreno-Martínez, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Jiménez de Anta, T.; Mensa, J.; et al. Differences in virulence factors among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli causing cystitis and pyelonephritis in women and prostatitis in men. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4445–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, V. Horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance by extended-spectrum β Lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Lab. Physicians 2011, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, N.; Fagan, E.J.; Ellington, M.J. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colom, K.; Pérez, J.; Alonso, R.; Fernández-Aranguiz, A.; Lariño, E.; Cisterna, R. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for detection of blaTEM, bla(SHV) and blaOXA-1 genes in Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 223, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.A.; González-Barrio, D.; Ruiz-Fons, F.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Torres, C. High frequency of B2 phylogroup among non-clonally related fecal Escherichia coli isolates from wild boars, including the lineage ST131. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Chanoine, M.H.; Bertrand, X.; Madec, J.Y. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, H.; Agace, W.; Klemm, P.; Schembri, M.; Mårild, S.; Svanborg, C. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 9827–9832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, M.R.; Yano, T.; da Silva Leite, D. Genotypic characterization of virulence factors in Escherichia coli strains from patients with cystitis. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2008, 50, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, G.; Hultgren, S.J. Structural biology of the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullt, B.; Bergsten, G.; Connell, H.; Röllano, P.; Gebretsadik, N.; Hull, R.; Svanborg, C. P fimbriae enhance the early establishment of Escherichia coli in the human urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féria, C.; Machado, J.; Correia, J.D.; Gonçalves, J.; Gaastra, W. Distribution of papG alleles among uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from different species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 202, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Shaik, S.; Ranjan, A.; Suresh, A.; Sarker, N.; Semmler, T.; Wieler, L.H.; Alam, M.; Watanabe, H.; Chakravortty, D.; et al. Genomic and Functional Characterization of Poultry Escherichia coli From India Revealed Diverse Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Lineages With Shared Virulence Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagrali, M. Siderophore production by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2009, 52, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeispour, M.; Ranjbar, R. Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genotyping of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalali, H.R.; Pourbakhsh, A.; Fallah, F.; Eslami, G. Genotyping of Virulence Factors of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli by PCR. Nov. Biomed. 2015, 3, 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, C.M.; Salvador, F.A.; Falsetti, I.N.; Vieira, M.A.M.; Blanco, J.; Blanco, J.E.; Blanco, M.; MacHado, A.M.O.; Elias, W.P.; Hernandes, R.T.; et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains may carry virulence properties of diarrhoeagenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 52, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisoy, M.; Aysev, D.; Ekim, M.; Özel, D.; Köse, S.K.; Özsoy, E.D.; Akar, N. Detection of virulence factors of Escherichia coli from children by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, L.J.; Méric, G.; Porcelli, I.; Sheppard, S.K.; Lucchini, S. Variation in siderophore biosynthetic gene distribution and production across environmental and faecal populations of Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.M.; Wright, P.J.; Lee, C.S.; Browning, G.F. Uropathogenic virulence factors in isolates of Escherichia coli from clinical cases of canine pyometra and feces of healthy bitches. Vet. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Delavari, P.; Kuskowski, M.; Stell, A.L. Phylogenetic Distribution of Extraintestinal Virulence-Associated Traits in Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 183, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, P.; Blanc, V.; Mora, A.; Dahbi, G.; Blanco, J.E.; Blanco, M.; López, C.; Andreu, A.; Navarro, F.; Alonso, M.P.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Potentially Pathogenic Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli Strains from Chicken and Pig Farms in Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2799–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Distribution of virulence factors in ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from the environment, livestock, food and humans. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhau, V.; Mendes, C.; Pena, A.; Mendonça, N.; Da Silva, G.J. Virulence and plasmidic resistance determinants of Escherichia coli isolated from municipal and hospital wastewater treatment plants. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, H.; Sib, E.; Gajdiss, M.; Klanke, U.; Lenz-Plet, F.; Barabasch, V.; Albert, C.; Schallenberg, A.; Timm, C.; Zacharias, N.; et al. Dissemination of multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria into German wastewater and surface waters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausner, M.; Wuertz, S. High Rates of Conjugation in Bacterial Biofilms as Determined by Quantitative In Situ Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 3710–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine 5th Revision 2016 Ranking of Medically Important Antimicrobials for Risk Management of Antimicrobial Resistance due to Non-Human Use; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bürgmann, H.; Frigon, D.; Gaze, W.H.; Manaia, C.M.; Pruden, A.; Singer, A.C.; Smets, B.F.; Zhang, T. Water and sanitation: An essential battlefront in the war on antimicrobial resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klümper, U.; Dechesne, A.; Smets, B.F. Protocol for Evaluating the Permissiveness of Bacterial Communities Toward Conjugal Plasmids by Quantification and Isolation of Transconjugants. In Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gillings, M.R.; Gaze, W.H.; Pruden, A.; Smalla, K.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhu, Y.G. Using the class 1 integron-integrase gene as a proxy for anthropogenic pollution. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiczek, R.; Krzyzanowska, B. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from bloodstream infections - Antimicrobial susceptibility, conjugative transfer of resistance genes and phylogenetic origin. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 23, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Rizzotti, L.; Felis, G.E.; Torriani, S. Horizontal gene transfer among microorganisms in food: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Food Microbiol. 2014, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).