First Emergence of Resistance to Macrolides and Tetracycline Identified in Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolates from Beef Feedlots in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

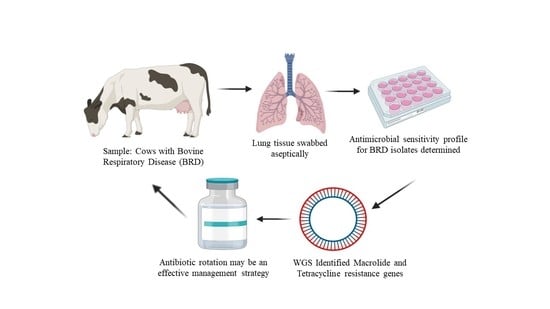

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation Procedures:

2.2. Isolate Storage and Transfer

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Molecular Typing-RAPD

2.5. Whole Genome Sequencing and Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MIC Distribution of M. Haemolytica and P. Multocida

3.2. Isolates from 2014–2015

3.3. Comparison of Resistance Profiles from 2016–2019 Reveals an Increase in Resistant Isolates over Time

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis Using RAPD

3.5. Correlating Phenotypic Resistance with Genotypic Resistance Elements Using Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rai, A.N.; Epperson, W.B.; Nanduri, B. Application of Functional Genomics for Bovine Respiratory Disease Diagnostics. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2015, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldspink, L.K.; Mollinger, J.L.; Barnes, T.S.; Groves, M.; Mahony, T.J.; Gibson, J.S. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Histophilus somni isolated from clinically affected cattle in Australia. Vet. J. 2015, 203, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaslus-Dancla, E.; Lesage-Decauses, M.C.; Leroy-Setrin, S.; Martel, J.L.; Coudert, P.; Lafont, J.P. Validation of random amplified polymorphic DNA assays by ribotyping as tools for epidemiological surveys of Pasteurella from animals. Vet. Microbiol. 1996, 52, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.D.; Fulton, R.W.; Lehenbauer, T.W.; Step, D.L.; Confer, A.W. The epidemiology of bovine respiratory disease: What is the evidence for predisposing factors? Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beker, M.; Rose, S.; Lykkebo, C.A.; Douthwaite, S. Integrative and Conjugative Elements (ICEs) in Pasteurellaceae Species and Their Detection by Multiplex PCR. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, C.W.; Abutarbush, S.M.; Morley, P.S.; Jim, G.K.; Pittman, T.J.; Schunicht, O.C.; Perrett, T.; Wildman, B.K.; Fenton, R.K.; Guichon, P.T.; et al. Microbiological and histopathological findings in cases of fatal bovine respiratory disease of feedlot cattle in Western Canada. Can. Vet. J. 2008, 49, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welsh, R.D.; Dye, L.B.; Payton, M.E.; Confer, A.W. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibilities of bacterial pathogens from bovine pneumonia: 1994–2002. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2004, 16, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyes, N.R.; Benedict, K.M.; Gow, S.P.; Booker, C.W.; Hannon, S.J.; McAllister, T.A.; Morley, P.S. Mannheimia haemolytica in feedlot cattle: Prevalence of recovery and associations with antimicrobial use, resistance, and health outcomes. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, E.; Hallewell, J.; Booker, C.; Tison, N.; Amat, S.; Alexander, T.W. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni isolated from the lower respiratory tract of healthy feedlot cattle and those diagnosed with bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 208, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.; Thomas, V.; Simjee, S.; Moyaert, H.; El Garch, F.; Maher, K.; Morrissey, I.; Butty, P.; Klein, U.; Marion, H.; et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility monitoring of respiratory tract pathogens isolated from diseased cattle and pigs across Europe: The VetPath study. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 172, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, I.; Page, S.; Rabiee, A.; Willams, S. A Survey of Antibacterial Product Use in the Australian Cattle Industry; Meat and Livestock Australia Report; Meat & Livestock Australia: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A.C.; Turnidge, J.; Collignon, P.; Looke, D.; Barton, M.; Gottlieb, T. Control of fluoroquinolone resistance through successful regulation, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.D.; Pratt, R.; Hart, W.S. Ajuntibiotic resistance in animals. Communable Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2003, 27, S121–S126. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, P.M.; McMeniman, N.; Lean, I.J. The medicine and epidemiology of bovine respiratory disease in feedlots. Aust. Vet. J. 2003, 81, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; McAllister, T.A. Antimicrobial usage and resistance in beef production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmolaize, B.; Rose, S.; Wilhelm, C.; Warrass, R.; Douthwaite, S. Combinations of macrolide resistance determinants in field isolates of Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4128–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, G.B.; Kadlec, K.; Sweeney, M.T.; Brzuszkiewicz, E.; Liesegang, H.; Daniel, R.; Murray, R.W.; Watts, J.L.; Schwarz, S. ICEPmu1, an integrative conjugative element (ICE) of Pasteurella multocida: Analysis of the regions that comprise 12 antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, C.P.; Blackall, P.J.; Wade, L.K.; Lowe, L.B. In-vitro antibacterial properties of tilmicosin against Australian isolates of Pasteurella multocida and Pasteurella haemolytica from cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 1993, 70, 391–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lleshi, A.G.N.; Trott, D.; Carr, M. The development of guidelines for post mortem and sample collection targeting the isolation of bovine respiratory disease bacterial pathogens in feedlots. Unpuplished work. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacterial Isolated from Animals; The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Portis, E.; Lindeman, C.; Johansen, L.; Stoltman, G. A ten-year (2000–2009) study of antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria that cause bovine respiratory disease complex— Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni—in the United States and Canada. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2012, 24, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, T.J.; Vermunt, J.J.; Malmo, J. Diseases of Cattle in Australasia: A Comprehensive Textbook; New Zealand Veterinary Association Foundation for Continuing Education: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, P.M.V.; Mahony, T.J. Evaluation of Practices Used to Reduce the Incidence of Bovine Respiratory Disease in Australian Feedlots; Meat and Livestock Australia Report; Meat & Livestock Australia: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, M.T.; Lubbers, B.V.; Schwarz, S.; Watts, J.L. Applying definitions for multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance and pandrug resistance to clinically significant livestock and companion animal bacterial pathogens-authors’ response. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; ECDC. The 2013 joint ECDC/EFSA report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks published. Eurosurveillance 2015, 20, 21021. [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss, E.J.; Hodgson, J.C.; Schmitt-van de Leemput, E.; Dagleish, M.P.; Zadoks, R.N. Molecular epidemiology of Pasteurella multocida in dairy and beef calves. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 151, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachamkin, I.; Bohachick, K.; Patton, C.M. Flagellin gene typing of Campylobacter jejuni by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, E.; Guerrini, A.; Ballestri, M.; Varchi, G.; Ferroni, C.; Martella, E.; Columbaro, M.; Moret, F.; Reddi, E. Keratin nanoparticles co-delivering Docetaxel and Chlorin e6 promote synergic interaction between chemo- and photo-dynamic therapies. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 199, 111598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. Probable Inference, the Law of Succession, and Statistical Inference. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1927, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavananthasivam, J.; Dassanayake, R.P.; Kugadas, A.; Shanthalingam, S.; Call, D.R.; Knowles, D.P.; Srikumaran, S. Proximity-dependent inhibition of growth of Mannheimia haemolytica by Pasteurella multocida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6683–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MSD. Animal Health. Intervet International B.V. and Intervet Inc. Available online: https://www.msd-animal-health.com.au/about-us/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Barnes, T.; Hay, K.; Morton, J.; Mahony, T. Epidemiology and Management of Bovine Respiratory Disease in Feedlot Cattle; Meat and Livestock Australia Report; Meat & Livestock Australia: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klima, C.L.; Zaheer, R.; Cook, S.R.; Booker, C.W.; Hendrick, S.; Alexander, T.W.; McAllister, T.A. Pathogens of bovine respiratory disease in North American feedlots conferring multidrug resistance via integrative conjugative elements. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger, S.; Sullivan, K.; Jordan, D.; Caraguel, C.; Page, S.; Cusack, P.; Frith, D.; Trott, D. Antimicrobial use and stewardship practices on Australian beef feedlots. Aust. Vet. J. 2020, 98, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, A.M.; Hu, D.; Totton, S.C.; Scott, N.; Winder, C.B.; Wang, B.; Wang, C.; Glanville, J.; Wood, H.; White, B.; et al. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of injectable antibiotic options for the control of bovine respiratory disease in the first 45 days post arrival at the feedlot. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2019, 20, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, P.M. Effect of mass medication with antibiotics at feedlot entry on the health and growth rate of cattle destined for the Australian domestic market. Aust. Vet. J. 2004, 82, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, E.; Workentine, M.; Crepieux, T.; Miller, C.; Regev-Shoshani, G.; Schaefer, A.; Alexander, T. Effects of nasal instillation of a nitric oxide-releasing solution or parenteral administration of tilmicosin on the nasopharyngeal microbiota of beef feedlot cattle at high-risk of developing respiratory tract disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 115, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, R.M.; Klima, C.; Allan, N.; Matheson-Bird, H.; Schatz, C.; Ajitkumar, P.; Otto, S.J.; Peters, D.; Schmid, K.; Olson, M.; et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacteria That Cause Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex in Alberta, Canada. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magstadt, D.R.; Schuler, A.M.; Coetzee, J.F.; Krull, A.C.; O’Connor, A.M.; Cooper, V.L.; Engelken, T.J. Treatment history and antimicrobial susceptibility results for Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni isolates from bovine respiratory disease cases submitted to the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory from 2013 to 2015. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2018, 30, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Garch, F.; de Jong, A.; Simjee, S.; Moyaert, H.; Klein, U.; Ludwig, C.; Marion, H.; Haag-Diergarten, S.; Richard-Mazet, A.; Thomas, V.; et al. Monitoring of antimicrobial susceptibility of respiratory tract pathogens isolated from diseased cattle and pigs across Europe, 2009–2012: VetPath results. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 194, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leotta, G.A.; Chinen, I.; Vigo, G.B.; Gugliada, J.; Rivas, M. Evaluation of two techniques of molecular subtyping to study Pasteurella multocida. Rev. Argent. De Microbiol. 2006, 38, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A.; Shivachandra, S.B.; Saxena, M.K.; Kumar, A.A.; Singh, V.P.; Srivastava, S.K. Molecular variability among strains of Pasteurella multocida isolated from an outbreak of haemorrhagic septicaemia in India. Vet. Res. Commun. 2004, 28, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Mahmoud, M.A.E.-F.; Ahmed, S. Molecular Characterization of Isolated Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida from Infected Sheep and Goats Using RAPD and ERIC Markers. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2018, 13, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad-Aski, H.; Tabatabaei, M. Molecular characterization of Pasteurella multocida isolates obtained from poultry, ruminant, cats and dogs using RAPD and REP-PCR analysis. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2016, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, S.P.; Eamens, G.J.; Ha, H.; Walker, M.J.; Chin, J.C. Demonstration that Australian Pasteurella multocida isolates from sporadic outbreaks of porcine pneumonia are non-toxigenic (toxA-) and display heterogeneous DNA restriction endonuclease profiles compared with toxigenic isolates from herds with progressive atrophic rhinitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 1998, 47, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.D.; Fulton, R.W.; Dabo, S.M.; Lehenbauer, T.W.; Confer, A.W. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic characterization methods for Pasteurella multocida isolates from fatal cases of bovine respiratory disease. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010, 22, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, K.; Michael, G.B.; Sweeney, M.T.; Brzuszkiewicz, E.; Liesegang, H.; Daniel, R.; Watts, J.L.; Schwarz, S. Molecular basis of macrolide, triamilide, and lincosamide resistance in Pasteurella multocida from bovine respiratory disease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2475–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, G.B.; Eidam, C.; Kadlec, K.; Meyer, K.; Sweeney, M.T.; Murray, R.W.; Watts, J.L.; Schwarz, S. Increased MICs of gamithromycin and tildipirosin in the presence of the genes erm(42) and msr(E)-mph(E) for bovine Pasteurella multocida and Mannheimia haemolytica. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1555–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeDonder, K.D.; Harhay, D.M.; Apley, M.D.; Lubbers, B.V.; Clawson, M.L.; Schuller, G.; Harhay, G.P.; White, B.J.; Larson, R.L.; Capik, S.F.; et al. Observations on macrolide resistance and susceptibility testing performance in field isolates collected from clinical bovine respiratory disease cases. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 192, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, G.B.; Bossé, J.T.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Pasteurellaceae of Veterinary Origin. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Valera, E.; Kyselkova, M.; Ahmed, E.; Sladecek, F.X.J.; Goberna, M.; Elhottova, D. Native soil microorganisms hinder the soil enrichment with antibiotic resistance genes following manure applications. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furushita, M.; Shiba, T.; Maeda, T.; Yahata, M.; Kaneoka, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Torii, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Ohta, M. Similarity of tetracycline resistance genes isolated from fish farm bacteria to those from clinical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5336–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, C.S.; Jones, A.L. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a transposon (Tn5393) carrying streptomycin resistance genes in Erwinia amylovora and other Gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Millan, A.; Escudero, J.A.; Gutierrez, B.; Hidalgo, L.; Garcia, N.; Llagostera, M.; Dominguez, L.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Multiresistance in Pasteurella multocida is mediated by coexistence of small plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3399–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Millan, A.; Escudero, J.A.; Catalan, A.; Nieto, S.; Farelo, F.; Gibert, M.; Moreno, M.A.; Dominguez, L.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Beta-lactam resistance in Haemophilus parasuis Is mediated by plasmid pB1000 bearing blaROB-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2260–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- San Millan, A.; Garcia-Cobos, S.; Escudero, J.A.; Hidalgo, L.; Gutierrez, B.; Carrilero, L.; Campos, J.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Haemophilus influenzae clinical isolates with plasmid pB1000 bearing blaROB-1: Fitness cost and interspecies dissemination. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livrelli, V.O.; Darfeuille-Richaud, A.; Rich, C.D.; Joly, B.H.; Martel, J.L. Genetic determinant of the ROB-1 beta-lactamase in bovine and porcine Pasteurella strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988, 32, 1282–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolates | 2014/2015 | 2016/2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mannheimia haemolytica | 11 | 23 | 21 | 33 | 88 |

| Pasteurella multocida | 12 | 40 | 23 | 65 | 140 |

| Total | 23 | 63 | 44 | 98 | 228 |

| Antimicrobial Agent | MIC Breakpoint (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | |

| Ampicillin | ≤0.03 | 0.06–0.12 | ≥0.25 |

| Ceftiofur | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 |

| a Clindamycin | - | - | - |

| Danofloxacin | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ≥1 |

| Enrofloxacin | ≤0.25 | 0.5–1 | ≥2 |

| Florfenicol | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 |

| Gentamicin | - | - | - |

| Gamithromycin | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 |

| Neomycin | - | - | - |

| Penicillin | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ≥1 |

| Sulphadimethoxine | - | - | - |

| b Specinomycin | ≤32 | 64 | ≥128 |

| Tetracycline | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 |

| Tiamulin | - | - | - |

| c Tilmicosin | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | - | - | - |

| Tulathromycin | ≤16 | 32 | ≥64 |

| Tylosin tartrate | - | - | - |

| d Tildipirosin | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 |

| Mannheimia haemolytica (n = 55) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC Distribution (µg/mL) a | MIC50 (µg/mL) | MIC90 (µg/mL) | CI (95%) b | |||||||||||||||

| Antibiotics | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | |||

| Ampicillin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||

| Ceftiofur | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||

| Clindamycin | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0 | 80.0 | 14.5 | 1.8 | 8 | 16 | 0–8.13 | |||||||

| Danofloxacin | 98.2 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||||

| Enrofloxacin | 98.2 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||

| Florfenicol | 7.3 | 89.1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||

| Gamithromycin | 98.2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||||

| Gentamicin | 3.6 | 94.5 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||

| Neomycin | 30.9 | 69.1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||||

| Tetracycline | 98.2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||

| Penicillin | 47.3 | 43.6 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||

| Sulphadimethoxine | 100 | 256 | 256 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||||||

| Spectinomycin | 0 | 20.0 | 78.2 | 1.8 | 16 | 32 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||||

| Tiamulin | 0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0 | 12.7 | 80.0 | 3.6 | 8 | 16 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||

| Tilmicosin | 0 | 45.5 | 50.9 | 3.6 | 4 | 8 | 0–8.13 | |||||||||||

| Trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole | 100 | 2 | 2 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||||||

| Tulathromycin | 1.8 | 3.6 | 36.4 | 49.1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||

| Tylosin tartrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 12.7 | 81.8 | 32 | >32 | 0–8.13 | |||||||

| Tildipirosin | 96.4 | 3.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0–8.13 | ||||||||||

| Mannheimia haemolytica (n = 33) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC Distribution (µg/mL) a | MIC50 (µg/mL) | MIC90 (µg/mL) | CI (95%) b | |||||||||||||||

| Antibiotics | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | |||

| Ampicillin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||

| Ceftiofur | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||

| Clindamycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.1 | 63.6 | 30.3 | 8 | 16 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||

| Danofloxacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||||

| Enrofloxacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||||

| Florfenicol | 0 | 97.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||

| Gamithromycin | 90.9 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | 1 | 2 | 0.2–17.5 | ||||||||||

| Gentamicin | 0 | 97.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||||

| Neomycin | 15.2 | 84.8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||||

| Tetracycline | 93.9 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||||

| Penicillin | 75.8 | 24.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||

| Sulphadimethoxine | 87.9 | 2.1 | 256 | 512 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||||||

| Spectinomycin | 0 | 54.5 | 45.5 | 0 | 16 | 32 | 0–12.98 | |||||||||||

| Tiamulin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.1 | 60.6 | 27.3 | 16 | 32 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||

| Tilmicosin | 6.1 | 27.3 | 60.6 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4 | 8 | 0.2–17.5 | ||||||||||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 100 | 2 | 2 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||||||||

| Tulathromycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 97.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | 8 | 8 | 0.2–17.5 | |||||||

| Tylosin tartrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.2 | 84.8 | 32 | ≥64 | 0–12.98 | |||||||

| Tildipirosin | 84.8 | 12.1 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0–12.98 | ||||||||||

| Pasteurella multocida (n = 75) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC Distribution (µg/mL) a | MIC50 (µg/mL) | MIC90 (µg/mL) | CI (95%) b | |||||||||||||||

| Antibiotics | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | |||

| Ampicillin | 96.0 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.25 | 1 | 1.0–12.0 | |||||||

| Ceftiofur | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–6.07 | |||||||||

| Clindamycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 16.0 | 34.7 | 44.0 | 16 | >16 | 0–6.07 | |||||||

| Danofloxacin | 98.7 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–6.07 | |||||||||||

| Enrofloxacin | 98.7 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||

| Florfenicol | 62.7 | 37.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0–6.07 | |||||||||

| Gamithromycin | 93.3 | 1.3 | 0 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 1 | 8 | 0.5–10.2 | ||||||||||

| Gentamicin | 22.7 | 53.3 | 22.7 | 0 | 1.3 | 2 | 4 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||

| Neomycin | 54.7 | 33.3 | 8.0 | 0 | 4.0 | 8 | 16 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||

| Tetracycline | 88.0 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 8 | 3.3–17.2 | ||||||||||

| Penicillin | 93.3 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | 0.12 | 2 | 1.0–12.0 | |||||||

| Sulphadimethoxine | 100 | 256 | 256 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||||||

| Spectinomycin | 10.7 | 52.0 | 37.3 | 0 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.07 | |||||||||||

| Tiamulin | 2.6 | 0 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 14.7 | 58.7 | 20.0 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||

| Tilmicosin | 0 | 69.3 | 28.0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | 4 | 8 | 0.5–10.2 | |||||||||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 100 | 2 | 2 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||||||

| Tulathromycin | 56.0 | 30.7 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.7 | 1 | 8 | 0.5–10.2 | |||||||

| Tylosin tartrate | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 2.7 | 16.0 | 45.3 | 30.7 | 4.0 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.07 | |||||||

| Tildipirosin | 89.3 | 2.7 | 0 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 1 | 8 | 0–6.07 | ||||||||||

| Pasteurella multocida (n = 65) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC Distribution (µg/mL) a | MIC50 (µg/mL) | MIC90 (µg/mL) | CI (95%) b | |||||||||||||||

| Antibiotics | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | |||

| Ampicillin | 95.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1.2–13.8 | ||||||||

| Ceftiofur | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||

| Clindamycin | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 49.2 | 38.5 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.95 | |||||||

| Danofloxacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||||

| Enrofloxacin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||||

| Florfenicol | 83.1 | 16.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||

| Gamithromycin | 78.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21.5 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 12.7–33.8 | |||||||||

| Gentamicin | 16.9 | 69.2 | 12.3 | 1.5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||||

| Neomycin | 67.7 | 13.8 | 18.5 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||||

| Tetracycline | 75.4 | 4.6 | 0 | 1.5 | 15.4 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 8 | 10.3–30.4 | |||||||||

| Penicillin | 92.3 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.6 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 1.2–13.8 | |||||||

| Sulphadimethoxine | 100 | 256 | 256 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||||||||

| Spectinomycin | 10.8 | 64.6 | 24.6 | 0 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||||

| Tiamulin | 1.5 | 0 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 18.5 | 60.0 | 15.4 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||

| Tilmicosin | 27.7 | 36.9 | 9.2 | 1.5 | 24.6 | 8 | 32 | 15.1–37.1 | ||||||||||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 100 | 2 | 2 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||||||||

| Tulathromycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76.9 | 1.5 | 0 | 21.5 | 8 | 64 | 12.7–33.8 | ||||||||

| Tylosin tartrate | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 3.1 | 9.2 | 64.6 | 21.5 | 16 | 32 | 0–6.95 | ||||||||

| Tildipirosin | 72.3 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0–6.95 | |||||||||

| Year | Total Isolates | S | Tet-R | Mac-R | Tet-Mac-R | Pen-Amp-R | Amp-Pen-Tet-R | Amp-Pen-Tet-Mac-R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016–2017 | 40 | 35 | 3 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2018 | 23 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2019 | 65 | 43 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 ** |

| Total | 140 | 109 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| CLN | ST | Year | RP | RAPD P | Antimicrobial Resistance Genes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aphA1 | blaROB-1 | msr(E) | mph(E) | strA | strB | sul2 | tet(Y) | Tet(H)-tet(R) | |||||

| P. m 17BRD-035 | QLD | 2017 | Amp, Pen and Tet | Cluster V | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 17BRD-041 | QLD | 2017 | Tet | Cluster V | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| P. m 17BRD-042 | QLD | 2017 | Tet | Cluster V | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| P. m 17BRD-038 | VIC | 2016 | Tet | Cluster V | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| P. m 17BRD-039 | QLD | 2017 | Tilm and Tul | Cluster V | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P.m 18BRD-047 | NSW | 2018 | Tet | Cluster V | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 18BRD-001 | QLD | 2018 | Amp, Pen and Tet | Cluster V | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 18BRD-005 | QLD | 2018 | Amp and Pen | Cluster V | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| P. m 18BRD-025 | SA | 2018 | Til and Tul | Cluster V | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P. m 19BRD-010 | NSW | 2019 | Tet | Cluster VI | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-011 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til, Tul and Tet | Cluster VI | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-014 | NSW | 2019 | Tet | Cluster VI | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m19BRD-016 | SA | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster VI | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P. m 19BRD-017 | SA | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster VI | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P. m 19BRD-020 | SA | 2019 | Gam, Tiland Tul | Cluster VI | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P. m 19BRD-032 | QLD | 2019 | Amp, Pen, Tet and Til | Cluster VI | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-039 | QLD | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster VI | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P. m 19BRD-042 | QLD | 2019 | Amp, Pen and Tet | Cluster VII | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-057 | QLD | 2019 | Amp, Pen, Tet and Til | Cluster VIII | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P.m 19BRD-085 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster IX | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P.m 19BRD-094 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster IX | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P.m 19BRD-098 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster IX | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P.m 19BRD-100 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster VIII | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| P.m 19BRD-104 | NSW | 2019 | Tet | Cluster VIII | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P.m 19BRD-106 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til, Tul and Tet | Cluster VIII | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | |

| P.m 19BRD-110 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til, Tul and Tet | Cluster VIII | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P.m 19BRD-111 | NSW | 2019 | Tet | Cluster VIII | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-112 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til, Tul and Tet | Cluster VIII | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-141 | NSW | 2019 | Tet | Cluster IV | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| P. m 19BRD-146 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til Tul and Tet | Cluster IV | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| M. h 19BRD-084 | NSW | 2019 | Gam, Til and Tul | Cluster III | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhamami, T.; Chowdhury, P.R.; Gomes, N.; Carr, M.; Veltman, T.; Khazandi, M.; Mollinger, J.; Deutscher, A.T.; Turni, C.; Mahdi, L.; et al. First Emergence of Resistance to Macrolides and Tetracycline Identified in Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolates from Beef Feedlots in Australia. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061322

Alhamami T, Chowdhury PR, Gomes N, Carr M, Veltman T, Khazandi M, Mollinger J, Deutscher AT, Turni C, Mahdi L, et al. First Emergence of Resistance to Macrolides and Tetracycline Identified in Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolates from Beef Feedlots in Australia. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(6):1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061322

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhamami, Tamara, Piklu Roy Chowdhury, Nancy Gomes, Mandi Carr, Tania Veltman, Manouchehr Khazandi, Joanne Mollinger, Ania T. Deutscher, Conny Turni, Layla Mahdi, and et al. 2021. "First Emergence of Resistance to Macrolides and Tetracycline Identified in Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolates from Beef Feedlots in Australia" Microorganisms 9, no. 6: 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061322

APA StyleAlhamami, T., Chowdhury, P. R., Gomes, N., Carr, M., Veltman, T., Khazandi, M., Mollinger, J., Deutscher, A. T., Turni, C., Mahdi, L., Venter, H., Abraham, S., Djordjevic, S. P., & Trott, D. J. (2021). First Emergence of Resistance to Macrolides and Tetracycline Identified in Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida Isolates from Beef Feedlots in Australia. Microorganisms, 9(6), 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061322