Simple Summary

This study investigates the potential of a nisin producer, i.e., Lactococcus lactis strain, in the making of Squacquerone cheese. The finding of this research indicates that the tested Lactococcus lactis strain represents a suitable candidate to be used as adjunct culture in Squacquerone cheesemaking since it improved the safety and sensory quality of the product without negatively affecting rheological characteristics and proteolysis.

Abstract

This research investigated the technological and safety effects of the nisin Z producer Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21, tested as an adjunct culture for the making of Squacquerone cheese in a pilot-scale plant. The biocontrol agent remained at a high level throughout the cheese refrigerated storage, without having a negative influence on the viability of the conventional Streptococcus thermophilus starter. The inclusion of CBM 21 in Squacquerone cheesemaking proved to be more effective compared to the traditional one, to reduce total coliforms and Pseudomonas spp. Moreover, the novel/innovative adjunct culture tested did not negatively modify the proteolytic patterns of Squacquerone cheese, but it gave rise to products with specific volatile and texture profiles. The cheese produced with CBM 21 was more appreciated by the panelists with respect to the traditional one.

1. Introduction

The launch on the market of new foods focused on the changing consumer needs and aimed to increase food safety and shelf-life is surely a pivotal challenge for the food industry, especially the dairy industry. In fact, innovative technologies able to increase the sustainability of the production processes (through the better exploitation of the raw materials), are important tools to open new business opportunities (providing benefits to consumers) [1,2]. Consequently, the interest in selected microbial strains able to increase cheese safety and shelf-life as well as to diversify the cheese sensory profile has markedly increased [3,4,5]. Interesting results have been obtained for several foods, including certain dairy products, by the use of an adjunct culture of Lactococcus lactis strains able to produce nisin [6,7,8,9]. Nisin was the first characterized bacteriocin and its use is permitted in some applications as a food preservative in the European Union [10,11,12,13]. Nisin, mainly the Z type, is characterized, both in vivo and in vitro, by strong antimicrobial activity against spoiling and pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria, associated with great stability and solubility in different food matrices [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. In addition, the use of nisin in combination with chemical–physical treatments, able to modify the cell wall permeability and consequently increase the interaction of nisin with the cytoplasmic membrane, can extend the nisin effectiveness to Gram-negative microorganisms including Pseudomonas spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp. [22].

The ability of L. lactis to produce nisin, together with many other antimicrobial compounds including hydrogen peroxide, CO2, organic acids, diacetyl, and other bacteriocins under several environmental conditions further enhances the high potential of this species of lactic acid bacteria for cheese quality improvement and innovation. In fact, L. lactis is reported to play a pivotal role, not only in product safety and shelf-life enhancement, but also in rapid milk acidification and in the sensory properties of several dairy products [23,24]. In fact, this species is reported to widely positively affect the aroma and the texture profiles (including moisture content, cohesiveness, softness) of dairy products, directly by its proteolytic and amino acid conversion activities [25], and the creation of optimal biochemical conditions during ripening [26]. Furthermore, L. lactis is widely recognized to play a key role during cheese making and early ripening. However, in late ripening, L. lactis is generally replaced mainly by lactobacilli, and some authors highlighted the presence of metabolically active cells of L. lactis in late ripening stages [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. In addition, L. lactis has extensive use in milk fermentation both in smaller scale traditional productions and in larger scale industrial applications [26,34]. Indeed, L. lactis strains, selected on the basis of their technological characteristics, are the main components of dairy starters for the manufacturing of cheese, sour cream, and buttermilk [35,36,37,38].

In this context, the aim of this research was to evaluate the potential of L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 (a previously characterized nisin Z-producer strain of dairy origin; [13]) in the diversification and improvement of quality, safety, and shelf-life of Squacquerone cheese.

Squacquerone is an Italian dairy product made from cow’s milk, typical of the Emilia Romagna region, that belongs to Stracchino-style cheeses, and is sold after a few days, packaged in simple, white, grease-proof paper, and is characterized by a white, shapeless, and grainy form with a delicate, sweet taste [39]. In addition, Squacquerone di Romagna is a protected designations of origin (PDO) product. Although it has regional importance, the few literature data show that it is characterized, similar to Crescenza cheese, by a low content of Na and an optimum Ca/P ratio compared to other cheeses [39]. More specifically, the impacts of the inclusion of L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 in a novel starter system on the cheese safety, shelf-life, and quality in terms of proteolytic and lipolytic activities, sensory, and volatile molecular profiles were assessed, considering the traditional product as a control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strain Conditions

The Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21, isolated from Mozzarella cheese [13], belongs to the Department of Biotechnology of Verona University. The strain was grown overnight (30 °C for 16 h) in M17 broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) under aerobic conditions. Microbial cultures were centrifuged at 8000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was washed twice with physiological solution (0.9% NaCl in distilled water) and suspended in commercial whole milk. As a starter culture for Squacquerone cheese production, commercial Streptococcus thermophilus St 0.20 (Sacco S.R.L., Como, Italy) was used as a freeze-dried culture. The starter was added to milk following the producer guidelines.

2.2. Production of Squacquerone Cheese

The production of Squacquerone cheese was done in a pilot-scale plant of a local cheese factory (Mambelli, Bertinoro, Italy). Two batches of pasteurized whole cow’s milk (100 L) were warmed up to a temperature of 42 °C. The starter S. thermophilus St 0.20 was inoculated at 6.0 Log Colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml. One batch was also inoculated with L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 at 7.0 Log CFU/mL. Forty min later, NaCl (0.7%) and 37 mL of rennet (12,000 international milk coagulating units (IMCU)/mL, 80% chymosin, and 20% pepsin, Bellucci Modena, Italy) were added to both batches. After coagulation, approximatively 20 min later, the curd was cut and moved to traditional baskets. The products were allowed to rest until a pH of 5.15 was reached and were then placed at 4 °C. The next day, the cheeses were packed under a modified atmosphere and stored at 4 °C up to 15 days. Three different types of cheese production on different days were performed for each cheese typology.

2.3. Microbiological Analyses and pH

Twenty g of cheese was added to 180 ml of sterile sodium citrate solution (20 g/L) and homogenized for 3 min by a stomacher (BagMixer 400P, Interscience, Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche, France). Serial dilutions of the homogenized samples were done in a physiological solution (0.9% NaCl), and aliquots of each dilution were spread onto the surface of different selective agar media. The enumeration of Streptococcus thermophilus was done on M17 agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) (42 °C, 48 h), while Lactococci were counted on M17 agar after 48 h at 30 °C. Moreover, the presence of the biocontrol agent was assured by checking the bacterial colony morphology and through molecular identification of the colonies by sequencing the 16S rRNA region according De Angelis et al. [40]. Total coliforms and yeasts were detected on Violet Red Bile agar (VRBA, Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) (37 °C, 24 h) and Yeast extract Peptone Dextrose agar (YPD, Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) (25 °C, 48 h), respectively. The presence of pathogenic species such as Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis, and Escherichia coli was monitored during the refrigerated storage of cheeses according to the ISO methods 11290, 6579, and 16649, respectively. pH was analyzed in cheese samples diluted in distilled water at a ratio 1:1 by a pH-meter (PH BASIC 20, Crison, Hach Lange, Italy).

2.4. Proteolysis, Lipolysis, Volatile Profiles

Proteolysis was examined by using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, US). The method proposed by Kuchroo and Fox [41] was used for protein extraction, while the running conditions were set up according to Tofalo et al. [42]. The lipid extraction from cheese samples and the analysis of the concentration of free fatty acids (FFAs) were done according to Vannini et al. [43]. The volatile molecular profiles of the cheese samples were detected by the solid-phase microextraction combined to chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS/SPME) technique following the methodology reported by Burns et al. [44]. The identification of the molecules was performed by using the mass spectra database from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST version 2011, Gaithersburg, US).

2.5. Textural Profile Analyses

The sample texture was determined after 1, 4, 6, and 13 days of refrigerated storage by a texture analyzer (TA-DHI, Stable MicroSystem, Godalming, UK) following the protocol reported by Patrignani et al. [45].

2.6. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation was performed after the refrigerated storage of the cheeses. The analysis was done by 25 trained panelists on 20 g of each cheese sample following the recommendations of Standard 8589 (ISO, 1988), as reported by Gallardo-Escamilla et al. [46]. The parameters evaluated were flavor, creaminess, color, bitter off-flavors, and overall acceptance. For each parameter, the grading scale ranged between 0 (low or poor) and 5 (high or excellent).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data are the mean of three biological replicates. The obtained data were analyzed by Statistica software (version 8.0; StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA). The significant differences among samples at the same storage time were detected using ANOVA followed by the LSD test at the p < 0.05 level. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the volatile molecular profiles of the cheese samples by Statistica software (version 8.0; StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Microbiological Analyses and pH

Cheeses produced with the two starter systems (i.e., only S. thermophilus St 0.20 and S. thermophilus St 0.20 plus L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21, thereafter named traditional and innovative cheeses) were analyzed after 1, 4, 6, 8, 13, and 15 days of storage. The recorded pH values are presented in Table 1. The addition of L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 did not modify the pH of the innovative cheese compared to the traditional one. In fact, one day after cheesemaking, the pH value of both the cheeses was 5.61 ± 0.13, while at the end of refrigerated storage, it was 5.38 ± 0.02 and 5.41 ± 0.02 for traditional and innovative cheeses, respectively. From a microbiological point of view, the presence of L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., and E. coli was verified at each time of sampling in both the cheese typologies. These pathogenic bacteria were not found during storage (data not shown). The microbiological results concerning S. thermophilus, L. lactis, total coliform, and yeast cell loads are reported in Table 2 and Table 3. The highest yeasts load were attained in the traditional cheese (1.4 Log CFU/g) after four days of refrigerated storage. However, at the end of the shelf-life (15 days), 1.0 Log CFU/g of yeasts were found in both cheese types. The total coliforms never exceeded 1.2 Log CFU/g in the innovative cheese during the shelf-life while they reached the highest values of 2.4 Log CFU/g in the traditional cheese after four days storage. However, in control cheese, after 15 days of storage, a coliform load of 1.7 Log CFU/g was detected.

Table 1.

pH evolution in innovative and traditional Squacquerone cheeses during refrigerated storage.

Table 2.

Cell load (Log CFU/g) of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactococcus lactis CBM 21 in innovative (INN) and traditional (C) Squacquerone cheeses during refrigerated storage. At the same time of storage, the means ± SD of S. thermophilus followed by different superscript letters (a or b) are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Cell load (Log CFU/g) of yeasts and total coliforms, in innovative and traditional Squacquerone cheeses during refrigerated storage. At the same time of storage, means ± SD followed by different superscript letters (a–c) are significantly different, p < 0.05.

The S. thermophilus starter attained cell loads of 7.1 and 7.3 Log CFU/g in the innovative and control cheese, respectively, after 1 day of refrigerated storage. In the traditional cheese, S. thermophilus remained quite stable for the considered period, while it increased during the refrigerated storage (up to 11 days of storage) in the innovative cheese. After 15 days, it attained a level of 7.2 Log CFU/g in the innovative cheese. The cell load of L. lactis subsp. lactis CMB 21 in the innovative cheese increased during the storage, reaching levels of 8.1 Log CFU/g after 15 days.

3.2. Lipolysis, Proteolysis, and Volatile Profile

The two types of cheeses were analyzed for their lipolytic, proteolytic, and volatile molecular profiles during the shelf-life. The lipolytic patterns were investigated after 1, 6, 11, and 15 days of storage, and the data obtained for free fatty acids (FFAs) are reported in Table 4. After 1 day of storage, the most released FFAs were C16:0, C18:0, C14:0, and C18:1 in both cheese types. The amount of FFAs increased over time for both cheeses. After 15 days, C18:1, which is considered a precursor for many aroma compounds, was significantly (p < 0.05) more abundant in the innovative cheese. The total amount of FFAs after 15 days of storage was significantly (p < 0.05) higher for the innovative cheese (373 ppm) than for the traditional one (291 ppm).

Table 4.

Free fatty acid (FFA)concentration (ppm) in innovative and traditional Squacquerone cheeses after 1, 6, 11, and 15 days of refrigerated storage. In the same line, for each FFA, means ± SD followed by different superscript letters (a–f) are significantly different, p < 0.05.

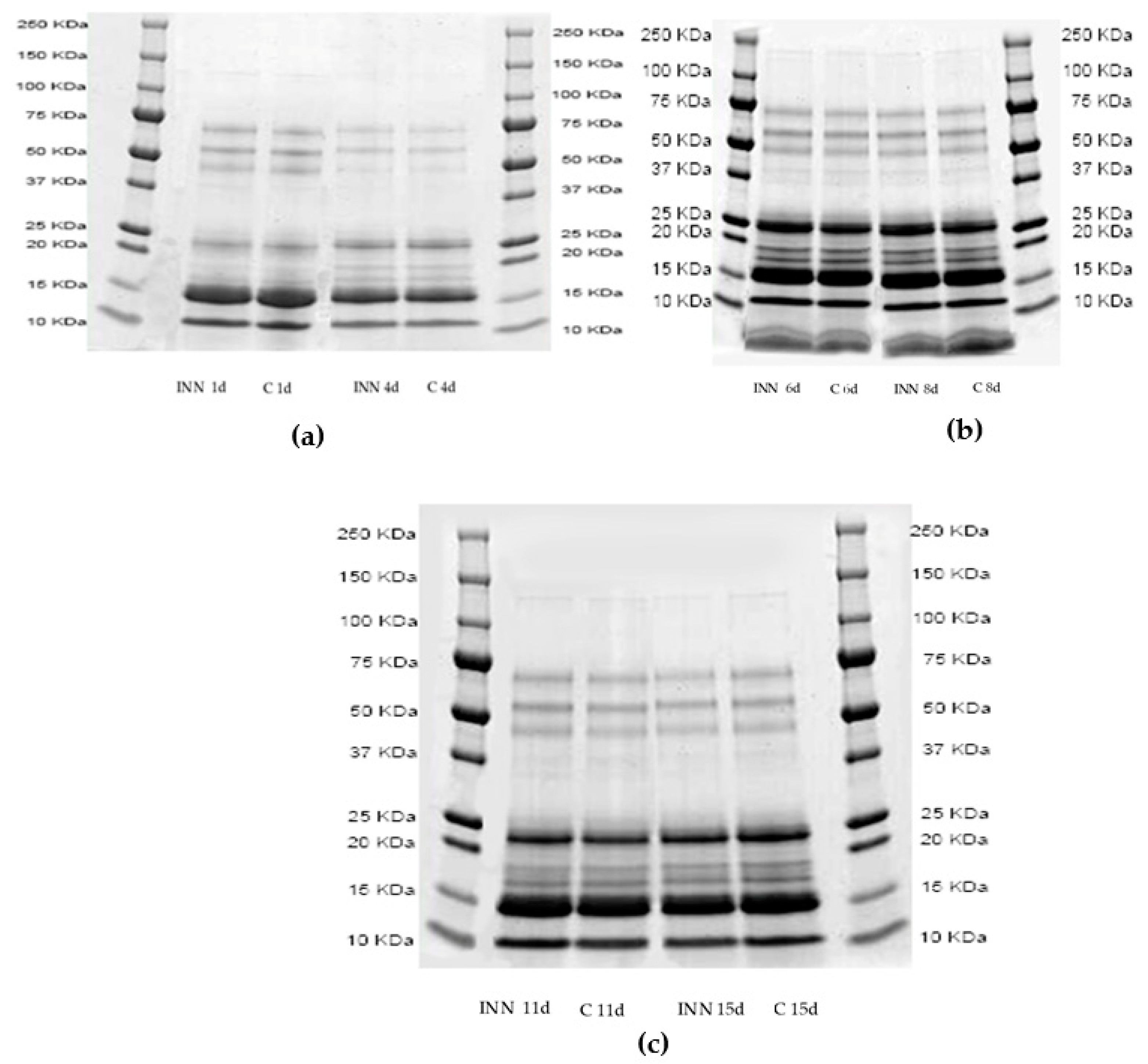

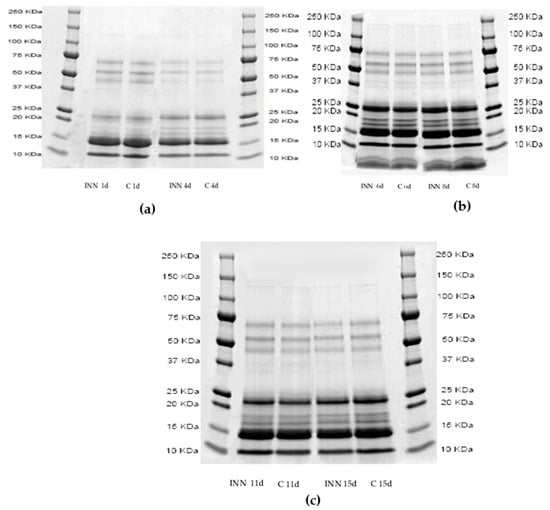

Figure 1a–c show the proteolytic patterns by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-page) of the two cheese types after 1, 4 (Figure 1a), 6, 8, (Figure 1b), 11, and 15 (Figure 1c) days of storage. It is clear that the cheese proteolytic profiles were not significantly influenced by the adjunct of CBM 21. After four days of storage, the bands corresponding to 50 Kilodalton (KDa) disappeared, compared to those of 1 day, while the bands with a molecular weight between 25 and 15 KDa increased in both the cheeses, regardless of the presence of CBM 21.

Figure 1.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis profiles of pH 4.6 soluble fractions of traditional (C) and innovative (INN) Squacquerone cheeses after 1 and 4 (a), 6 and 8 (b), and 11 and 15 (c) days.

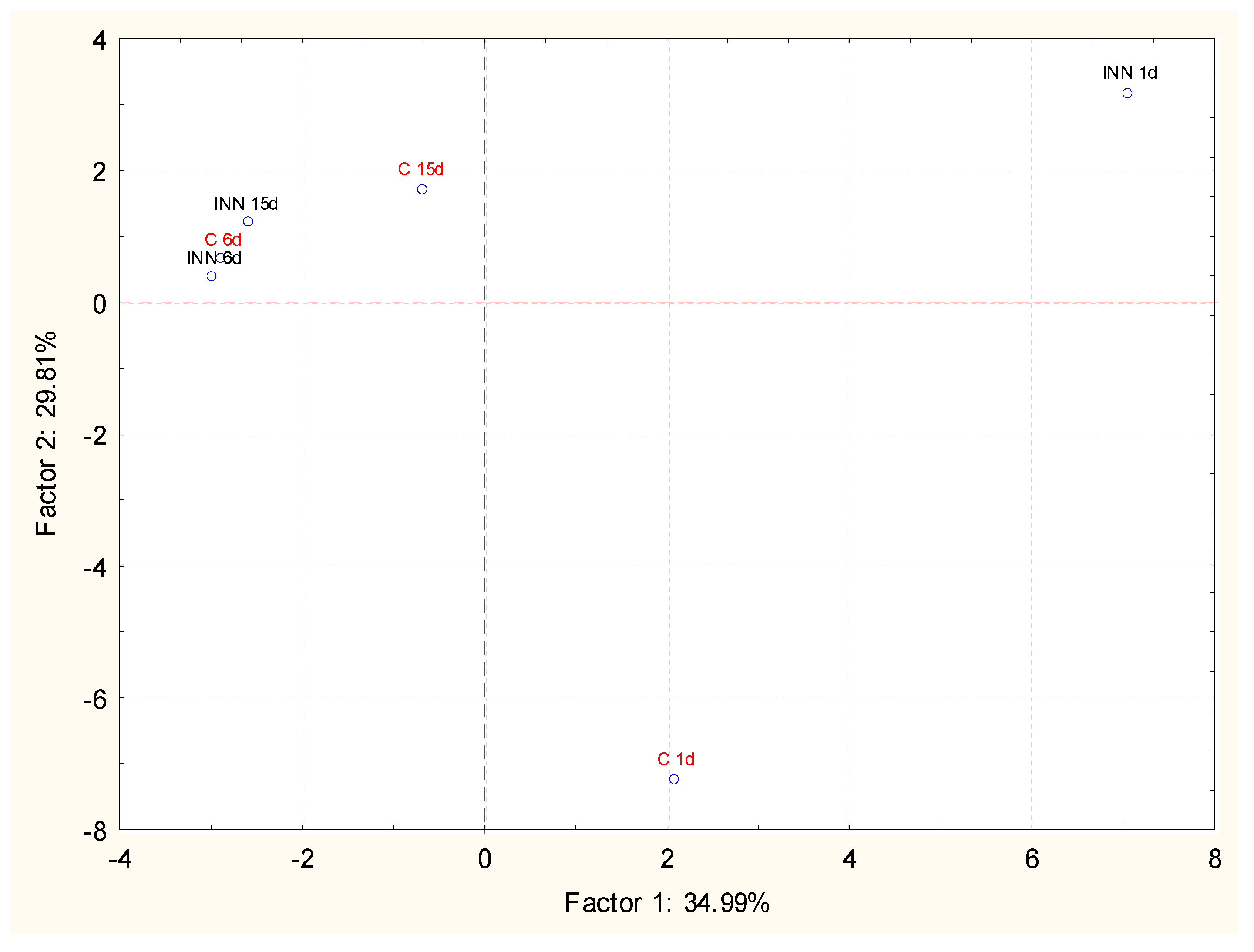

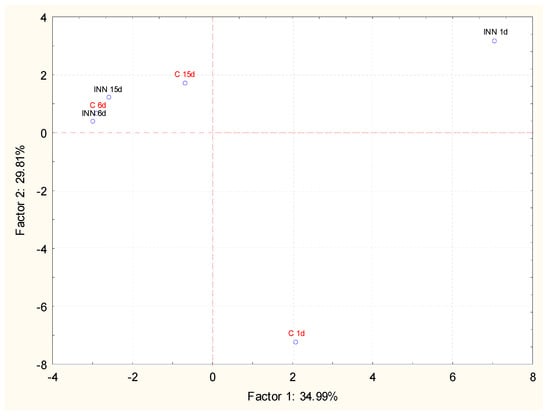

The volatile compounds of the cheeses, at different times of storage, were investigated by GC/MS coupled with solid phase micro extraction (SPME). This approach permitted us to detect 35 compounds belonging to different chemical classes. The main detected molecules expressed as a relative percentage are reported in Table 5. After 1 day of storage, 2-butanone and 2-3 butanedione were detected in similar amounts in both the traditional and innovative cheeses, while 3 hydroxy-2 butanone was present at the highest level in the innovative cheese. During storage, a common trend observed, regardless of the type of sample, was the increase in acid and alcohol relative percentages associated with a decrease in esters and ketones. However, innovative cheeses were characterized by the highest amounts of acids, mainly short chain fatty acids such as butanoic, hexanoic, and octanoic acids, while in traditional cheeses, the highest increase in alcohol, mainly ethanol, was detected. In this framework, principal component analysis (PCA) in relation to the storage time was performed in order to better understand the effect of L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 on the volatile molecular profile of Squacquerone cheese. The projections of the cases and the variables in the factorial plane determined by principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) are shown in Figure 2. It is evident that the adjunct culture significantly affected the volatile molecular profile of Squacquerone at the beginning of the storage (1 day). In fact, the innovative cheese, after 1 day of refrigerated storage, was well separated along the PC2, which explained 29.81% of the variance among the samples, and, to a less extent, along PC1, which explained 34.99% of the variance. The most significant molecules responsible for the differences between the control and innovative cheeses were mainly ketones (i.e., 2-butanone, 3 hydroxy-2- butanone, acetone, 2,3- butanedione), acids (butanoic, hexanoic, and octanoic acids), and esters (acetic acid ethenyl ester and ethyl acetate). During the storage, the effects of the adjunct culture decreased. In fact, the two cheese typologies were still separated along PC1 and PC2 after 11 days, while, at the end of the refrigerated storage, they grouped together. After 15 days, both cheeses were characterized principally by 2-butanone and in lower amounts, by esters and alcohols.

Table 5.

Volatile compounds (expressed as relative percentages) detected through the GC-MS-SPME technique in innovative (INN) and traditional (C) Squacquerone cheeses after 1, 6, 11, and 15 days of storage. In the same line, relative to each FFA, means ± SD followed by different superscript letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Projection of the different Squacquerone cheeses (INN and C) on the factor plane (1-2) at different times of storage (1, 6, and 15 days) on the basis of the volatile profiles detected by solid-phase microextraction combined to chromatography-mass spectrometry technique (GC/MS SPME).

3.3. Texture Analyses

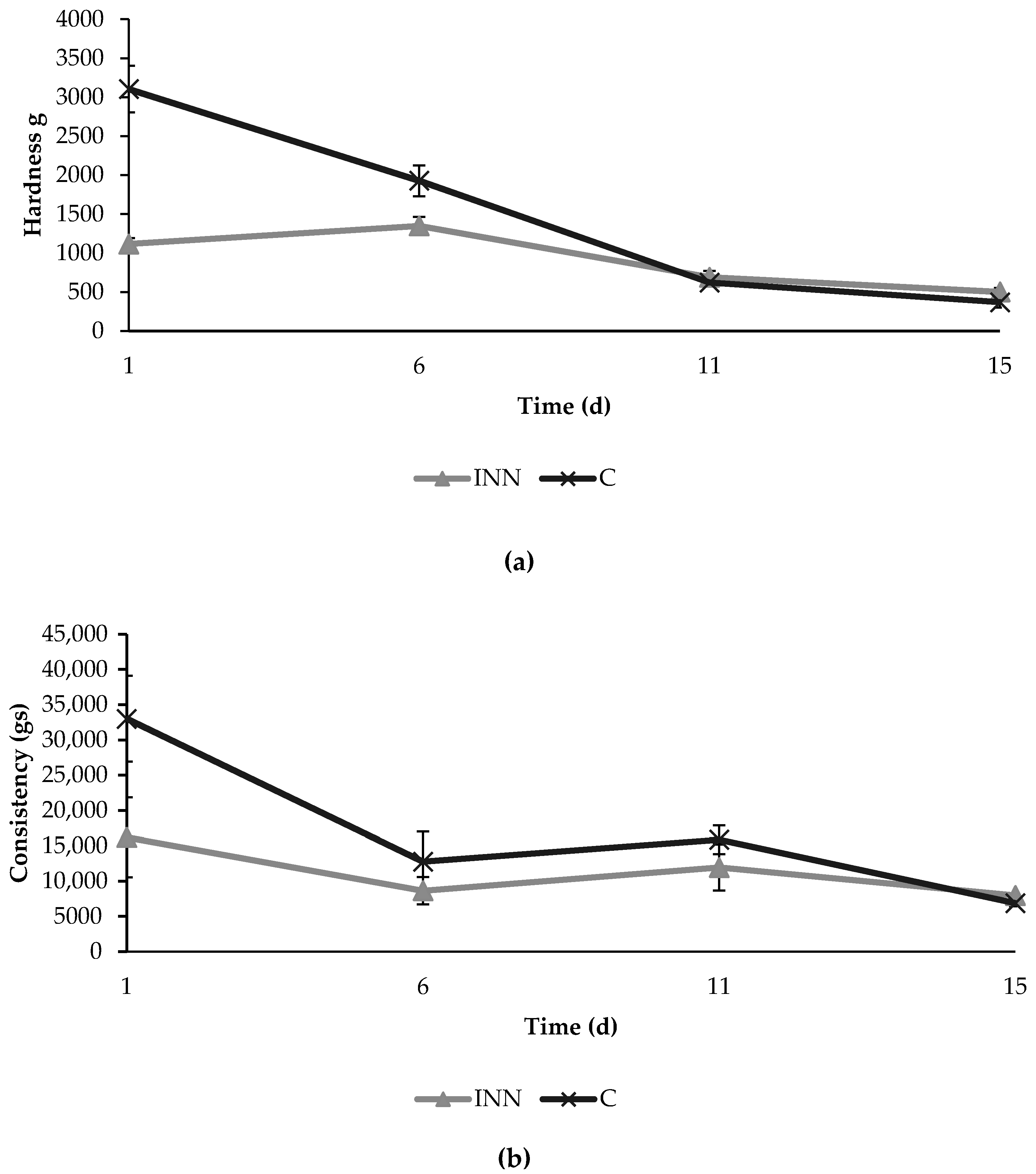

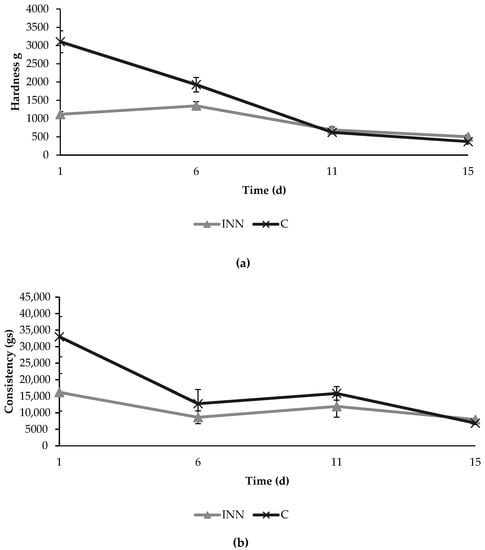

The texture analyses showed initial significant differences in hardness and consistency between the two different cheeses (Figure 3). In fact, at the beginning, the innovative cheeses were characterized by lower values of hardness and consistency compared to the control cheeses. However, these differences decreased over time, and no significant differences were found between the two cheese typologies after 15 days of refrigerated storage.

Figure 3.

Texture parameters in terms of hardness (a) and consistency (b) detected in traditional (C) and innovative (INN) Squacquerone cheeses during the refrigerated storage.

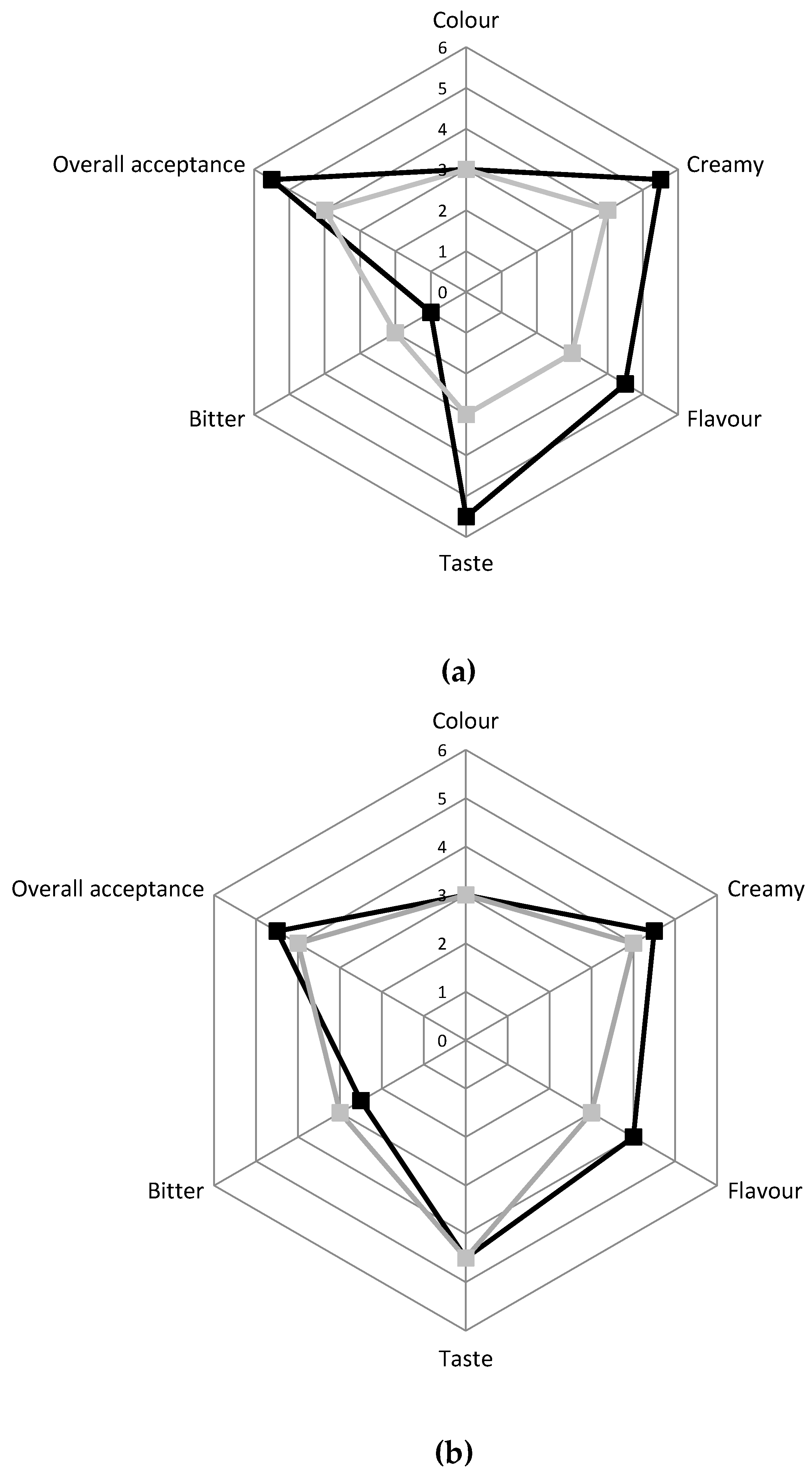

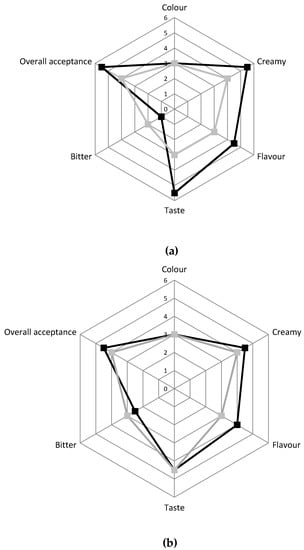

3.4. Sensory Analysis

The panel test, performed after 6 and 15 days of storage on the two different cheese typologies, indicated that the innovative cheese was preferred by the evaluators compared to the traditional one for all the attributes taken into consideration (Figure 4). Indeed, after six days, the innovative cheese had better scores compared to the traditional one for the overall acceptance, taste, creaminess, and flavor, while it received a lower score for the bitter after-taste. After 15 days of storage, the innovative cheese received a positive evaluation for all the attributes although the differences compared to traditional Squacquerone were reduced.

Figure 4.

Sensory evaluation of C ■ and INN ■ Squacquerone cheeses performed after 6 days (a) and 15 days (b) of refrigerated storage.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that the use of a selected strain of L. lactis subsp. lactis, which produces nisin Z, is suitable for the production of a high-quality cheese, endowed with a longer shelf-life, characterized by specific ripening profiles and improved safety and sensory features. Indeed, the microbiological data showed a significant reduction of the microorganisms (such as yeasts and Pseudomonas spp.) involved in the spoilage of both soft and hard cheeses [47,48,49,50]. In addition, total coliforms were totally inhibited in samples with the bacteriocin producer strain. Data obtained confirm the effectiveness of L. lactis as a biocontrol agent against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, thus improving the safety and shelf-life of dairy products [51,52]. In fact, the ability of nisin-producer strains to release this bacteriocin in dairy products during refrigerated storage has been documented [53]. In this framework, the suitability of the selected strain to be employed as an adjunct culture in Squacquerone cheese was demonstrated by its ability to reach a final cell load of 8.1 Log CFU/g at the end of storage, without negative effects on the viability of the conventional starter. Furthermore, the S. thermophilus starter strain was positively affected by the presence of CBM 21 in the early storage period. This stimulating effect on starter vitality can be ascribed to the higher early availability of FFAs, such as C18:1, which is an essential factor for the growth of lactic acid bacteria [44,54]. The addition of CBM 21 as an adjunct culture allowed a higher and precocious release of FFAs in cheese during the refrigerated storage. These data are in agreement with those of Ávila et al. [55], who attributed the precocious accumulation of FFAs in Hispanico cheese to the release of intracellular esterases by a nisin-producer strain, L. lactis subsp. lactis (INIA 415). Moreover, Ávila et al. [56] also observed an increased level of FFAs in semi-hard cheese inoculated with L. lactis subsp. lactis INIA 63. The authors attributed the increased lipolysis to the lysis of the starter culture (belonging to the species Lactobacillus helveticus) mediated by the bacteriocin and the subsequent release of its esterases. On the other hand, it is widely reported that lactic acid bacteria have a minor role in the lipolytic pattern of dairy products compared to the proteolytic one and their contribution is mainly in terms of esterase activity rather than the production of lipases [57,58]. On the other hand, the precocious release of FFAs can be responsible for the positive sensory evaluation of the innovative cheese. In fact, FFAs can directly contribute to the flavor and taste of dairy products (mainly short FFAs, responsible for the piquant notes) or can affect them as precursors of key aroma compounds [59]. By contrast, the strain L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21, used in the present research, did not contribute to the proteolytic patterns of the innovative cheese in a significant manner, although the positive contribution of such species to the ripening of several cheeses, due to the well-recognized protease and peptidase activities of this strain, is well known. This can be ascribed to the short time of storage and the low temperature adopted during the ripening. Indeed, it is well known that cheese proteolysis is affected by ripening time and temperature [60,61]. The increase in temperature has long been used to accelerate proteolysis and consequently to reduce the cheese ripening time [62,63]. The addition of L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 resulted in a different cheese volatile molecular profile. At the beginning of the refrigerated storage, the innovative cheese was characterized by the highest amount of 2,3 butanedione (diacetyl) and 2-butanone,3-hydroxy (acetoin). These aroma compounds, together with acetaldehyde and 2,3 butanediol, are generally regarded as the principal aroma compounds of yoghurt and soft-cheese-like products [64,65]. In particular, the diacetyl, derived from citrate metabolism, plays a crucial role in several dairy products affecting the creamy and buttery flavor, and its presence is characteristic of Camembert, Cheddar, and Emmental cheeses [66,67], as well as of soft cheeses [68]. The ability of L. lactis to produce these key volatile compounds is well known, and this is one of the main reasons why it is exploited at the industrial level [8,69]. The differences analytically detected between the two types of cheeses were perceived by the panelists involved in this research: the innovative cheese was the most appreciated for the entire considered storage time, which resulted in a creamier flavor, particularly after 4–6 days. These data are in agreement with the texture analysis, since the cheese produced by adding CBM 21 was characterized by lower hardness and consistency. Although proteolysis, which plays a crucial role in the texture development [70], was not significantly different between the two types of Squacquerone, the cheese texture can be affected by other factors, such as cheese composition, processing conditions, and the ripening process [63].

However, the difference detected both by GC/MS-SPME and the panel test, as well as the texture differences decreased over time were reduced at the end of the shelf-life.

The results of this study indicate that the use of the strain L. lactis CBM 21 is suitable to obtain a high-quality Squacquerone cheese. Although PDO production imposes precise protocols to obtain safe products, the use of Lactococcus lactis CBM 21 could represent a further strategy to improve the safety of Squacquerone cheese, imparting good and innovative quality features. In this view, in a saturated market such as the dairy one, the possibility to obtain a product with improved quality characteristics and better safety may represent a good strategy for product differentiation.

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed that the nisin Z-producer L. lactis subsp. lactis CBM 21 was suitable for the production of Squacquerone cheese. In fact, its addition as a biocontrol agent had positive effects not only on the safety, but also on the overall quality of the cheese, giving rise to a product potentially appreciated by the consumers for its specific cheese volatile and textural profiles. Therefore, the use of a starter system which includes strains with superior technological and safety attributes could contribute to enlarge the gamut of high-quality dairy products, improving their safety without having any detrimental effects on the sensory characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P. and R.L.; methodology, L.R., F.P. and R.L.; software, L.S.; validation, L.S., E.S., F.P. and S.T.; formal analysis, L.S. and E.S.; investigation, L.S., M.D. and R.L.; resources, L.S. and F.P.; data curation, L.S., R.L. and F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P.; writing—review and editing, L.S., E.S., S.T. and R.L.; visualization, L.S. and R.L.; supervision, S.T. and R.L.; project administration, F.P. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Agri-food Innovation and the Functional Food Market in Europe: Concerns and Challenges. EuroChoices 2013, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, R.; Farahani, P.; Grunow, M. Quality, safety and sustainability in food distribution: A review of quantitative operations management approaches and challenges. OR Spectr. 2010, 32, 863–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Ferrari, I.; de Souza, J.V.; Ramos, C.L.; da Costa, M.M.; Schwan, R.F.; Dias, F.S. Selection of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria from goat dairies and their addition to evaluate the inhibition of Salmonella typhi in artisanal cheese. Food Microbiol. 2016, 60, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrotiene, K.; Kasnauskyte, N.; Serniene, L.; Gölz, G.; Alter, T.; Kaskoniene, V.; Maruska, A.S.; Malakauskas, M. Characterization and application of newly isolated nisin producing Lactococcus lactis strains for control of Listeria monocytogenes growth in fresh cheese. LWT 2018, 87, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoorde, K.; Van Leuven, I.; Dirinck, P.; Heyndrickx, M.; Coudijzer, K.; Vandamme, P.; Huys, G. Selection, application and monitoring of Lactobacillus paracasei strains as adjunct cultures in the production of Gouda-type cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkerroum, N.; Oubel, H.; Zahar, M.; Dlia, S.; Filali-Maltouf, A. Isolation of a bacteriocin-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and applicatin to control Listeria monocytogenes in Moroccan jben. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 89, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Bello, B.; Cocolin, L.; Zeppa, G.; Field, D.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C. Technological characterization of bacteriocin producing Lactococcus lactis strains employed to control Listeria monocytogenes in Cottage cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, V.T.T.; Lo, R.; Bansal, N.; Turner, M.S. Characterisation of Lactococcus lactis isolates from herbs, fruits and vegetables for use as biopreservatives against Listeria monocytogenes in cheese. Food Control 2018, 85, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Calzada, J.; Arqués, J.L.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Nuñez, M.; Medina, M. Antimicrobial activity of pediocin-producing Lactococcus lactis on Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, T. Food and Dietary Supplement Package Labeling—Guidance from FDA’s Warning Letters and Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 92–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Salin, V.; Williams, G.W. NISIN and the Market for Commercial Bacteriocins; TAMRC Consumer and Product 2005, Research Report CP-01-05; Texas Agribusiness Mark Research Center: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Siroli, L.; Patrignani, F.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Vernocchi, P.; Del Chierico, F.; Russo, A.; Torriani, S.; Putignani, L.; Gardini, F.; Lanciotti, R. Effect of thyme essential oil and Lactococcus lactis CBM21 on the microbiota composition and quality of minimally processed lamb’s lettuce. Food Microbiol. 2017, 68, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siroli, L.; Patrignani, F.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Vannini, L.; Salvetti, E.; Torriani, S.; Gardini, F.; Lanciotti, R. Use of a nisin-producing Lactococcus lactis strain, combined with natural antimicrobials, to improve the safety and shelf-life of minimally processed sliced apples. Food Microbiol. 2016, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, J.; Montville, T.J.; Nes, I.F.; Chikindas, M.L. Bacteriocins: Safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Fadda, M.E.; Deplano, M.; Melis, R.; Pomata, R.; Pisano, M.B. Antilisterial activity of nisin-like bacteriocin-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis isolated from traditional Sardinian dairy products. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 376428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Arauz, L.J.; Jozala, A.F.; Mazzola, P.G.; Vessoni Penna, T.C. Nisin biotechnological production and application: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharsallaoui, A.; Oulahal, N.; Joly, C.; Degraeve, P. Nisin as a Food Preservative: Part 1: Physicochemical Properties, Antimicrobial Activity, and Main Uses. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamuna, M.; Babusha, S.T.; Jeevaratnam, K. Inhibitory efficacy of nisin and bacteriocins from Lactobacillus isolates against food spoilage and pathogenic organisms in model and food systems. Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.; Guenther, S.; Steffan, S.; Scherer, S. A pediocin-producing Lactobacillus plantarum strain inhibits Listeria monocytogenes in a multispecies cheese surface microbial ripening consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1854–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinos, A.C.; Abriouel, H.; Ben Omar, N.; Valdivia, E.; López, R.L.; Maqueda, M.; Cañamero, M.M.; Gálvez, A. Effect of immersion solutions containing enterocin AS-48 on Listeria monocytogenes in vegetable foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7781–7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Doucette, C.; Fillmore, S. Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from cheeses and yogurts. AMB Express 2012, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, C.; Castellano, P.; Vignolo, G. Reduction of Escherichia coli population following treatment with bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria and chelators. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E.; Alegría, Á.; Delgado, S.; Martín, M.C.; Mayo, B. Comparative phenotypic and molecular genetic profiling of wild Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strains of the L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris genotypes, isolated from starter-free cheeses made of raw milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5324–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, J.T.M.; Ayad, E.H.E.; Hugenholtz, J.; Smit, G. Microbes from raw milk for fermented dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, G.; Smit, B.A.; Engels, W.J.M. Flavour formation by lactic acid bacteria and biochemical flavour profiling of cheese products. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, M.; Cocolin, L.; Dolci, P. Fate of Lactococcus lactis starter cultures during late ripening in cheese models. Food Microbiol. 2016, 59, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandria, V.; Ferrocino, I.; De Filippis, F.; Fontana, M.; Rantsiou, K.; Ercolini, D.; Cocolin, L. Microbiota of an Italian Grana-like cheese during manufacture and ripening, unraveled by 16S rRNA-based approaches. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3988–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desfossés-Foucault, É.; LaPointe, G.; Roy, D. Dynamics and rRNA transcriptional activity of lactococci and lactobacilli during Cheddar cheese ripening. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, P.; Alessandria, V.; Rantsiou, K.; Bertolino, M.; Cocolin, L. Microbial diversity, dynamics and activity throughout manufacturing and ripening of Castelmagno PDO cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, A.B.; Mayo, B. Microbial diversity and succession during the manufacture and ripening of traditional, Spanish, blue-veined Cabrales cheese, as determined by PCR-DGGE. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 110, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, W.; Takamiya, M.; Vogensen, F.K.; Lillevang, S.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Jakobsen, M. Characterization of bacterial populations in Danish raw milk cheeses made with different starter cultures by denaturating gradient gel electrophoresis and pyrosequencing. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantsiou, K.; Urso, R.; Dolci, P.; Comi, G.; Cocolin, L. Microflora of Feta cheese from four Greek manufacturers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 126, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggirello, M.; Dolci, P.; Cocolin, L. Detection and viability of Lactococcus lactis throughout cheese ripening. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cretenet, M.; Laroute, V.; Ulvé, V.; Jeanson, S.; Nouaille, S.; Even, S.; Piot, M.; Girbal, L.; Le Loir, Y.; Loubière, P.; et al. Dynamic analysis of the Lactococcus lactis transcriptome in cheeses made from milk concentrated by ultrafiltration reveals multiple strategies of adaptation to stresses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beresford, T.P.; Fitzsimons, N.A.; Brennan, N.L.; Cogan, T.M. Recent advances in cheese microbiology. Int. Dairy J. 2001, 11, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, M.B.; Fadda, M.E.; Melis, R.; Ciusa, M.L.; Viale, S.; Deplano, M.; Cosentino, S. Molecular identification of bacteriocins produced by Lactococcus lactis dairy strains and their technological and genotypic characterization. Food Control 2015, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazanova, M.; Huppertz, T.; Beerthuyzen, M.; van Schalkwijk, S.; Janssen, P.; Wels, M.; Kok, J.; Bachmann, H. Cell surface properties of Lactococcus lactis reveal milk protein binding specifically evolved in dairy isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lante, A.; Lomolino, G.; Cagnin, M.; Spettoli, P. Content and characterisation of minerals in milk and in Crescenza and Squacquerone Italian fresh cheeses by ICP-OES. Food Control 2006, 17, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Siragusa, S.; Berloco, M.; Caputo, L.; Settanni, L.; Alfonsi, G.; Amerio, M.; Grandi, A.; Ragni, A.; Gobbetti, M. Selection of potential probiotic lactobacilli from pig feces to be used as additives in pelleted feeding. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchroo, C.N.; Fox, P.F. Soluble nitrogen in Cheddar cheese: Comparison of extraction procedures. Milchwissenschaft 1982, 37, 331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Tofalo, R.; Schirone, M.; Fasoli, G.; Perpetuini, G.; Patrignani, F.; Manetta, A.C.; Lanciotti, R.; Corsetti, A.; Martino, G.; Suzzi, G. Influence of pig rennet on proteolysis, organic acids content and microbiota of Pecorino di Farindola, a traditional Italian ewe’s raw milk cheese. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannini, L.; Patrignani, F.; Iucci, L.; Ndagijimana, M.; Vallicelli, M.; Lanciotti, R.; Guerzoni, M.E. Effect of a pre-treatment of milk with high pressure homogenization on yield as well as on microbiological, lipolytic and proteolytic patterns of “Pecorino” cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 128, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, P.G.; Patrignani, F.; Tabanelli, G.; Vinderola, G.C.; Siroli, L.; Reinheimer, J.A.; Gardini, F.; Lanciotti, R. Potential of high pressure homogenisation on probiotic Caciotta cheese quality and functionality. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrignani, F.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Mathara, J.M.; Siroli, L.; Gardini, F.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Lanciotti, R. Use of homogenisation pressure to improve quality and functionality of probiotic fermented milks containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus BFE 5264. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016, 69, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Escamilla, F.J.; Kelly, A.L.; Delahunty, C.M. Mouthfeel and flavour of fermented whey with added hydrocolloids. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Corsetti, A.; Smacchi, E.; Zocchetti, A.; De Angelis, M. Production of Crescenza Cheese by Incorporation of Bifidobacteria. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, R.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Patrignani, F.; Paparella, A.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Serio, A.; Suzzi, G. Effects of milk treatment with dynamic high pressure on microbial populations, and lipolytic and proteolytic profiles of Crescenza cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2004, 57, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, F.; Osimani, A.; Taccari, M.; Milanović, V.; Garofalo, C.; Clementi, F.; Polverigiani, S.; Zitti, S.; Raffaelli, N.; Mozzon, M.; et al. Impact of thistle rennet from Carlina acanthifolia All. subsp. acanthifolia on bacterial diversity and dynamics of a specialty Italian raw ewes’ milk cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 255, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, F.; Taccari, M.; Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Polverigiani, S.; Garofalo, C.; Foligni, R.; Mozzon, M.; Zitti, S.; Raffaelli, N.; et al. Yeast and mould dynamics in Caciofiore della Sibilla cheese coagulated with an aqueous extract of Carlina acanthifolia All. Yeast 2016, 33, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, L.H.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, P. Bacteriocins: Biological tools for bio-preservation and shelf-life extension. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallinteri, L.D.; Kostoula, O.K.; Savvaidis, I.N. Efficacy of nisin and/or natamycin to improve the shelf-life of Galotyri cheese. Food Microbiol. 2013, 36, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrino-López, A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Use of nisin and other bacteriocins for preservation of dairy products. Int. Dairy J. 2008, 18, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, L.; Marttinen, N.; Alatossava, T. Fats and fatty acids as growth factors for Lactobacillus delbrueckii. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 24, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, M.; Calzada, J.; Garde, S.; Nuñez, M. Effect of a bacteriocin-producing Lactococcus lactis strain and high-pressure treatment on the esterase activity and free fatty acids in Hispánico cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Calzada, J.; Garde, S.; Nuñez, M.; Nuñez Lipolysis, M.; NuñezNu, M. Lipolysis of semi-hard cheese made with a lacticin 481-producing Lactococcus lactis strain and a Lactobacillus helveticus strain. Lait 2007, 87, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.M.; Williams, A.G. The role of the nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in Cheddar cheese ripening. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2004, 57, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Corsetti, A.; Tosti, N.; Rossi, J.; Corbo, M.R.; Gobbetti, M. Characterization of Non-Starter Lactic Acid Bacteria from Italian Ewe Cheeses Based on Phenotypic, Genotypic, and Cell Wall Protein Analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, D.T.; Furey, A.; Kilcawley, K.N. Free fatty acids quantification in dairy products. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbettia, M.; Lanciotti, R.; De Angelis, M.; Rosaria Corbo, M.; Massini, R.; Fox, P. Study of the effects of temperature, pH, NaCl, and a(w) on the proteolytic and lipolytic activities of cheese-related lactic acid bacteria by quadratic response surface methodology. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1999, 25, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinee, T.P.; Wilkinson, M.G.; Mulholland, E.O.; Fox, P.F. Influence of Ripening Temperature, Added Commercial Enzyme Preparations and Attenuated Mutant (Lac−) Lactococcus lactis Starter on the Proteolysis and Maturation of Cheddar Cheese. Irish J. Food Sci. Technol. 1991, 15, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, J.A.; Wilkinson, M.G.; Delahunty, C.M.; Wallace, J.M.; Morrissey, P.A.; Beresford, T.P. Application of descriptive sensory analysis and key chemical indices to assess the impact of elevated ripening temperatures on the acceleration of Cheddar cheese ripening. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahingil, D.; Hayaloglu, A.A.; Simsek, O.; Ozer, B. Changes in volatile composition, proteolysis and textural and sensory properties of white-brined cheese: Effects of ripening temperature and adjunct culture. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2014, 94, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. Volatile flavor compounds in yogurt: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlu-Özkaya, F.; Gün, İ. Aroma Compounds of Some Traditional Turkish Cheeses and Their Importance for Turkish Cuisine. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 5, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Winter, C.K. Diacetyl in Foods: A Review of Safety and Sensory Characteristics. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Gelais, D.; Lessard, J.; Champagne, C.P.; Vuillemard, J.C. Production of fresh Cheddar cheese curds with controlled postacidification and enhanced flavor. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1856–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milesi, M.M.; Wolf, I.V.; Bergamini, C.V.; Hynes, E.R. Two strains of nonstarter lactobacilli increased the production of flavor compounds in soft cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5020–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini, D.; Laroute, V.; Coddeville, M.; Le Bourgeois, P.; Loubière, P.; Ritzenthaler, P.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M.; Daveran-Mingot, M.L. New insights into Lactococcus lactis diacetyl- and acetoin-producing strains isolated from diverse origins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 160, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallami, L.; Kheadr, E.E.; Fliss, I.; Vuillemard, J.C. Impact of autolytic, proteolytic, and nisin-producing adjunct cultures on biochemical and textural properties of cheddar cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).