A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

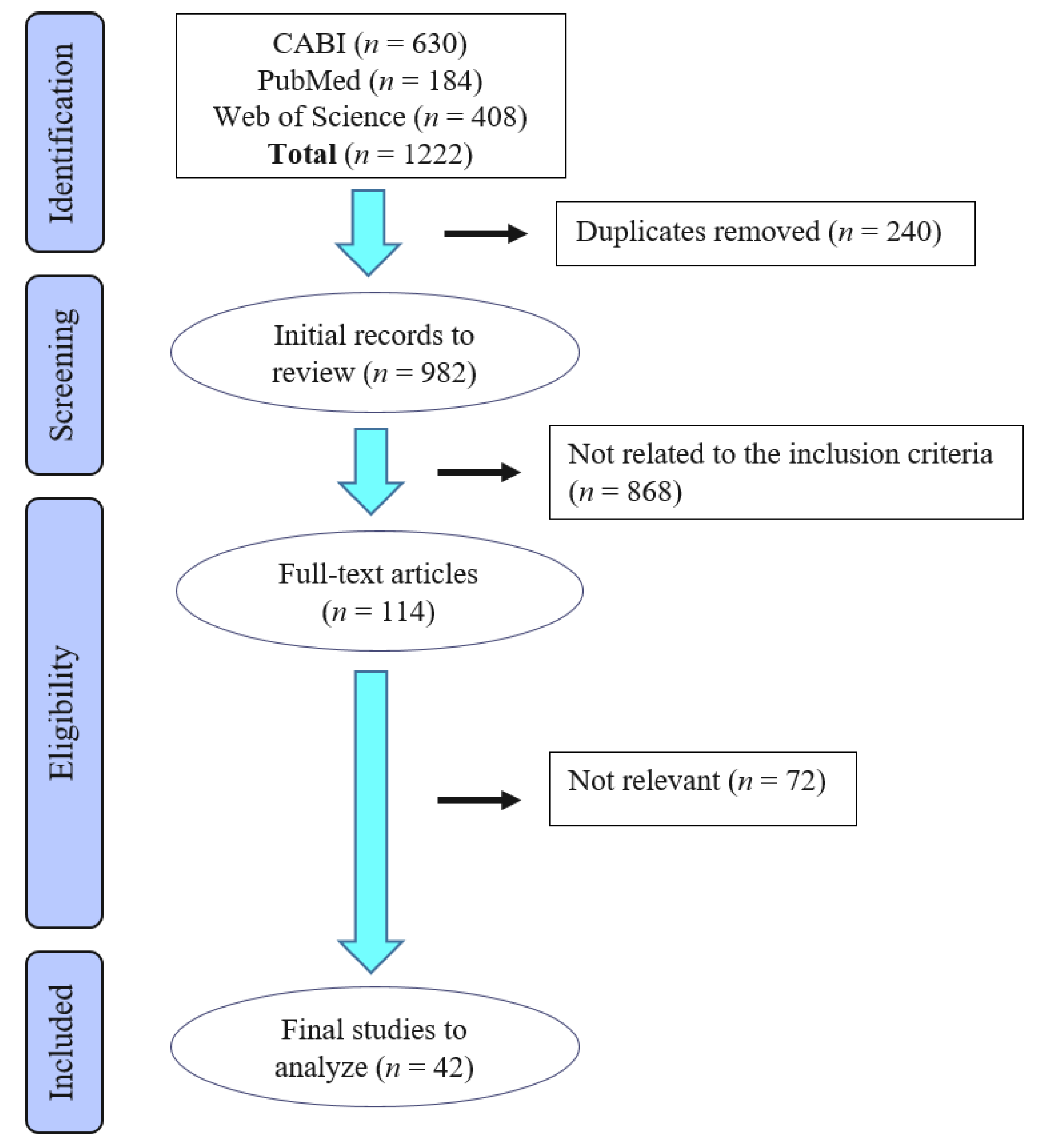

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Topic/Research Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. General Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection and Categorization

3. Results

3.1. Aromatherapy

3.1.1. Study Quality

3.1.2. Clinical Indications

3.1.3. Interventions and Controls

3.1.4. Outcome Variables

3.1.5. Clinical Effects

3.2. Gold Therapy

3.2.1. Study Quality

3.2.2. Clinical Indications

3.2.3. Interventions and Controls

3.2.4. Outcome Variables

3.2.5. Clinical Effects

3.3. Homeopathy

3.3.1. Study Quality

3.3.2. Clinical Indications

3.3.3. Intervention and Controls

3.3.4. Outcome Variables

3.3.5. Clinical Effects

3.4. Leeches (Hirudotherapy)

3.4.1. Study Quality

3.4.2. Clinical Indication, Intervention and Control, and Outcome Variables

3.4.3. Clinical Effects

3.5. Mesotherapy

3.5.1. Study Quality

3.5.2. Interventions and Controls

3.5.3. Outcome Variables

3.5.4. Clinical Effects

3.6. Mud Therapy

3.6.1. Study Quality

3.6.2. Clinical Indication, Intervention and Control, and Outcome Variables

3.6.3. Clinical Effects

3.7. Neural Therapy

3.7.1. Study Quality

3.7.2. Clinical Indications

3.7.3. Interventions and Controls

3.7.4. Outcome Variables

3.7.5. Clinical Effects

3.8. Sound (Music) Therapy

3.8.1. Study Quality

3.8.2. Clinical Indications, Dosage, and Outcome Variables

3.8.3. Clinical Effects

3.9. Vibration Therapy

3.9.1. Study Quality

3.9.2. Clinical Indications

3.9.3. Interventions and Controls

3.9.4. Outcome Variables

3.9.5. Clinical Effect

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lana, S.E.; Kogan, L.R.; Crump, K.A.; Graham, J.T.; Robinson, N.G. The use of complementary and alternative therapies in dogs and cats with cancer. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2006, 42, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, K.; Bolwell, C.F.; Rogers, C.W.; Gee, E.K. The use of allied health therapies on competition horses in the North Island of New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 2011, 59, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, B.; Fraschetto, C.; Villanueva, J.; Cantatore, F.; Bertuglia, A. Two multicenter surveys on equine back-pain 10 years apart. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; McKenzie, E.; Duesterdieck-Zellmer, K. International survey regarding the use of rehabilitation modalities in horses. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergenstrahle, A.; Nielsen, B.D. Attitude and behavior of veterinarians surrounding the use of complementary and alternative veterinary medicine in the treatment of equine musculoskeletal pain. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2016, 45, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans, J.B.A.; Stolk, P.W.T.; Weeren, P.R.; van Vaarkamp, H.; Barneveld, A. A survey of the workload and clinical skills in current equine practices in The Netherlands. Equine Vet. Educ. 2007, 19, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathie, R.T.; Clausen, J. Veterinary homeopathy: Meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Homeopathy 2015, 104, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathie, R.T.; Clausen, J. Veterinary homeopathy: Systematic review of medical conditions studied by randomised placebo-controlled trials. Vet. Rec. 2014, 175, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deisenroth, A.; Nolte, I.; Wefstaedt, P. Use of gold implants as a treatment of pain related to canine hip dysplasia—A review. Part 2: Clinical trials and case reports. Tierarztl. Prax. 2013, 41, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.2. 2021. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Statens Beredning för Medicinsk och Social Utvärdering (SBU). Utvärdering av Metoder i hälso- och Sjukvården och Insatser i Socialtjänsten: En Metodbok [in Swedish]. Stockholm. 2020. Available online: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/metodbok/eng_metodboken_no-longer-in-use.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Baldwin, A.L.; Chea, I. Effect of aromatherapy on equine heart rate variability. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 68, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.R.; Kleinman, H.F.; Browning, J. Effect of lavender aromatherapy on acute-stressed horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2013, 33, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, K.; Rabquer, B.; Heitman, E.; Streu, C.; Anderson, A. The use of equine lavender aromatherapy to relieve stress in trailered horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 63, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, M.; Sugiyama, A.; Tanabe, K.; Uchino, T.; Takeuchi, T. Evaluation of the effect of topical application of lavender oil on autonomic nerve activity in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2009, 70, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoon, A.S.; Al-Ashkar, E.A.; Kandil, O.M.; Shaban, A.M.; Khaled, H.M.; El Sayed, M.A.; El Shaer, M.M.; Shaalan, A.H.; Eisa, W.H.; Gamal, E.A.A.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity of plasmonic photothermal therapy (PPTT) using gold nanorods (GNRs) against mammary tumors in dogs and cats. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 2291–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ibrahim, I.; Ali, H.; Selim, S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Treatment of natural mammary gland tumors in canines and felines using gold nanorods-assisted plasmonic photothermal therapy to induce tumor apoptosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 4849–4863. [Google Scholar]

- Goiz-Marquez, G.; CaballeroS, S.H.; Rodriguez, C.; Sumano, H. Electroencephalographic evaluation of gold wire implants inserted in acupuncture points in dogs with epileptic seizures. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 86, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielm-Bjorkman, A.; Raekallio, M.; Kuusela, E.; Saarto, E.; Markkola, A.; Tulamo, R.M. Double-blind evaluation of implants of gold wire at acupuncture points in the dog as a treatment for osteoarthritis induced by hip dysplasia. Vet. Rec. 2001, 149, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, G.T.; Larsen, S.; Søli, N.; Moe, L. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the pain-relieving effects of the implantation of gold beads into dogs with hip dysplasia. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, C.; Decamp, C.E.; Stajich, M.; Flo, G.L.; Martinez, S.A.; Bennett, R.L.; Bebchuk, T. Gait analysis of dogs with hip dysplasia treated with gold bead implantation acupuncture. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2002, 15, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, G.T.; Larsen, S.; Søli, N.; Moe, L. Two years follow-up study of the pain-relieving effect of gold bead implantation in dogs with hip-joint arthritis. Acta Vet. Scand. 2007, 49, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balbueno, M.C.S.; Peixoto, K.C.; Coelho, C.P. Evaluation of the efficacy of Crataegus oxyacantha in dogs with early-stage heart failure. Homeopathy 2020, 109, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T.; Klinger, C.J.; Udraite, L.; Muelle, R.S. Effects of a homeopathic medication on clinical signs of canine atopic dermatitis. Tierarztl. Prax. 2020, 48, 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, S.; Stolt, P.; Braun, G.; Hellmann, K.; Reinhart, E. Effectiveness of the homeopathic preparation Zeel compared with carprofen in dogs with osteoarthritis. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2011, 47, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beceriklisoy, H.B.; Ozyurtlu, N.; Kaya, D.; Handler, J.; Aslan, S. Effectiveness of Thuja occidentalis and Urtica urens in pseudopregnant bitches. Wien. Tierarztl. Mon. 2008, 95, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hielm-Björkman, A.; Tulamo, R.M.; Salonen, H.; Raekallio, M. Evaluating complementary therapies for canine osteoarthritis—Part ii: A homeopathic combination preparation (Zeel). eCAM 2009, 6, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cracknell, D.; Mills, S. A double-blind placebo-controlled study into the efficacy of a homeopathic remedy for fear of firework noises in the dog (Canis familiaris). Vet. J. 2008, 177, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboutboule, R. Snake remedies and eosinophilic granuloma complex in cats. Homeopathy 2006, 95, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, S.; Varshney, J.P. Clinical management of babesiosis in dogs with homeopathic Crotalus horridus 200C. Homeopathy 2007, 96, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.B.; Hoare, J.; Lau-Gillard, P.; Rybnicek, J.; Mathie, R.T. Pilot study of the effect of individualised homeopathy on the pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis in dogs. Vet. Rec. 2009, 164, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaramiş, C.P.; Issautier, M.N.; Ulgen, S.S.; Demirtaş, B.; Olgun, E.D.; Or, M.E. Homeopathic treatments in 17 horses with stereotypic behaviours. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2016, 22, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.A.A.; Pavulraj, S.; Kumar, M.A.; Sangeetha, S.; Shamugapriya, R.; Sabithabanu, S. Therapeutic evaluation of homeopathic treatment for canine oral papillomatosis. Vet. World 2020, 13, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bodey, A.L.; Almond, C.J.; Holmes, M.A. Double-blinded randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial of individualised homeopathic treatment of hyperthyroid cats. Vet. Rec. 2017, 180, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchiori, M.S.; Schafer Da, S.A.; Glombowsky, P.; Campigotto, G.; Favaretto, J.A.R.; Jaguezeski, A.M. Homeopathic product in dog diets modulate blood cell responses. Arch. Vet. Sci. 2019, 24, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulstich, A.; Lutz, H.; Hellmann, K. Comparison of the effed of Zeel® ad us. vet. in lameness of horses caused by non-infectious arthropathy to the effect of hyaluronic acid. Der Prakt. Tierarzt. 2006, 87, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Cayado, P. Effectiveness of homeopathic remedies in severe laminitic horses. Homeopathy 2016, 105, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, K. Blutegeltherapie bei Hufrehe der Pferde. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Studie. Z. Fur Ganzheitl. Tiermed. 2010, 24, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.C.; Santos, A.; Fernandes, A. Evaluation of the effect of mesotherapy in the management of back pain in police working dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2018, 45, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.; Jorge, P.; Santos, A. Comparison of two mesotherapy protocols in the management of back pain in police working dogs: A retrospective study. Top. Companion Med. 2021, 43, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, A.; Bányai, A.; Koltay, I.; Ujj, Z.; Such, N.; Mándó, Z.; Novinszky, P. Veterinary use of thermal water and mud from Lake Hévíz for equestrian injury prevention and rehabilitation. Ecocycles 2019, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Monsalvo, A.; Vázquez-Chagoyán, J.C.; Gutiérrez, L.; Sumano, H. Clinical efficacy of neural therapy for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Acta Vet. Hung. 2008, 56, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenmenger, E.; Kasper, I.; Eisenmenger, M. Observations of the pain syndrome in theloin and hip region of horses and experimental treatment with neural therapy. Pferdeheilkunde 1989, 5, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedzierski, W.; Janczarek, I.; Stachurska, A.; Wilk, I. Comparison of effects of different relaxing massage frequencies and different music hours on reducing stress level in race horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 53, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, H.H.F.; Zimmer, L.; Haase, L.; Perrier, J.; Peham, C. Effects of whole body vibration on the horse: Actual vibration, muscle activity, and warm-up effect. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 51, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsberghe, B.T. Long-term and immediate effects of whole body vibration on chronic lameness in the horse: A pilot study. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 48, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackechnie-Guire, R.; Mackechnie-Guire, E.; Bush, R.; Wyatt, R.D.; Fisher, M.; Cameron, L. A controlled, blinded study investigating the effect that a 20-minute cycloidal vibration has on whole horse locomotion and thoracolumbar profiles. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 71, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstanjen, B.; Balai, M.; Gajewski, Z.; Furmanczyk, K.; Bondzio, A.; Remy, B.; Hartmann, H. Short-term whole body vibration exercise in adult healthy horses. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2013, 16, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, I.F.C.; Rahal, S.C.; Shimono, J.; Rahal, S.C.; Tsunemi, M.; Takahira, R.; Teixeira, R.C. Whole-body vibration exercise on hematology and serum biochemistry in healthy dogs. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2017, 32, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowlin, C.; Nielsen, B.; Mills, J.; Robison, C.; Schott, H.; Peters, D. Acute and prolonged effects of vibrating platform treatment on horses: A pilot study. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 62, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, C.S.; Sigler, D.; Vogelsang, M. Muscle metabolic effects of whole-body vibration in yearling horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 52, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, K.; Spooner, H.; Hoffman, R.; Haffner, J. The effect of whole body vibration on bone density and other parameters in the exercising horse. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 52, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulak, E.S.; Spooner, H.S.; Haffner, J.C. Influence of whole body vibration on bone density in the stalled horse. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 52, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Sprunger, L.K. Survey of colleges and schools of veterinary medicine regarding education in complementary and alternative veterinary medicine. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2011, 239, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Kessler, R.C.; Van Rompay, M.L.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Wilkey, S.A.; Appel, S.; Davis, R.B. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: Results from a national survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 135, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.-W.; Chen, K.-Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, L.-S.; Lin, J.-H. Acupuncture for general veterinary practice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2001, 63, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knight, N. The Behaviours and Attitudes Surrounding the use of Equine Complementary and Alternative Medicine Amongst Horse-Carers in the Auckland Region; Unitec Institute of Technology: Auckland, New Zealand, 2011; Available online: https://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/1917 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Cerciello, S.; Rossi, S.; Visonà, E.; Corona, K.; Oliva, F. Clinical applications of vibration therapy in orthopaedic practice. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2016, 19, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Control Group | Study Sample | Intervention and Dosage | Outcome Variables | Main Results | Study Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin and Chea, 2018 [12] | RCT (exper-imental) | Cross over | 9 horses Inclusion: Sound horses Exclusion: - | A. Humidified lavender oil and humidified air (control) B. Humidified chamomile oil and humidified air (control) 1 week washout. | Heart rate variability (HRV) Root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) between the interbeat intervals (indicator of parasympathetic tone) | Lavender transiently increased RMSSD and reduced percentage of very low-frequency HRV oscillations immediately after treatment. Chamomile had variable effects, none of which reached significance. | High |

| Ferguson, Kleinman. Browning, 2013 [13] | RCT (experi-mental) | Cross over | 7 horses Inclusion: Sound horses Exclusion: - | Aromatherapy-treated horses = humidified air with a 20% mixture of 100% pure lavender essential oil for 15 min. Control = humidified air. | Heart rate (HR) Respiratory rate (RR) | Change in HR after treatment was significantly greater after aromatherapy compared with the control treatment. The RR did not differ. | Moderate/high |

| Heitman, Rabquer, Heitman, Streu, Anderson, 2017 [14] | RCT (experi-mental) | Cross over | 8 horses Inclusion: Sound horses Exclusion: - | During a trailer ride (stressor), the horses received humidified air as the control and lavender aromatherapy (LA) as the treatment. | Heart rate (HR) Cortisol Norepinephrine | The average difference between the baseline and stressed measurements of HR and cortisol increased in both groups when the horses were transported. There was no difference in the HRs of the control and treatment horses; there was a difference in cortisol levels, with lower levels in the treated group. | Moderate/high |

| Komiya et al., 2009 [15] | RCT (experimental) | Cross-over | 5 dogs Inclusion: sound dogs Exclusion: - | Lavender oil (0.18 mL) or saline (0.9% NaCl) solution (0.18 mL) was topically applied to the inner pinnas of both ears of all dogs at 8:30, 12:00, 15:30, and 19:00 on day 2. Each trial was duplicated in each dog, with an interval of 3 to 4 days between trials. | An ambulatory electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor was placed on each dog and 48-h ECGs were recorded. Spectral indices of heart rate variability, power in the high-frequency range, and the ratio of low-frequency to high-frequency power were calculated as an indirect estimate of autonomic nerve activity. | When dogs were treated with lavender oil, the mean heart rate was significantly lower during the period of 19:00 to 22:30 on day 2 compared with when dogs were treated with saline solution. High-frequency power during the period of 15:30 to 19:00 was significantly higher when dogs were treated with lavender oil compared with when dogs were treated with saline solution. | Moderate/high |

| Study | Study Design | Control Group | Study Sample | Intervention and Dosage | Outcome Variables | Main Results | Study Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdoon et al., 2016 [16] | Case study | No | 10 dogs and 6 cats Inclusion: spontaneous mammary tumor. Exclusion: - | Plasmonic photothermal therapy to evaluate the cytotoxic effect of intratumoral injection of 75 μg gold nanorods/kg of body weight followed by direct exposure to 2 W/cm2 near infra-red laser light for 10 min on ablation of mammary tumor. | Case history, clinical, ultrasound, and histopathological examination. | Results showed that 62.5%, 25%, and 12.5% of treated animals showed complete remission, partial remission, and no response, respectively. Tumor was relapsed in four cases of initially responding animals (25%). Overall survival rate was extended to 315.5 ± 20.5 days. | Moderate/high |

| Ali et al., 2015 [17] | Case study | No | 5 dogs and 2 cats Inclusion: natural mammary gland tumors Exclusion: - | A regime of three low plasmonic photothermal therapy doses at two-week intervals that ablated tumors. | Histopathology, X-ray, blood profiles, and comprehensive examinations were used before and after treatment. | Histopathology results showed an obvious reduction in the cancer grade shortly after the first treatment and a complete regression after the third treatment. | Moderate/high |

| Goiz-Marquez et al., 2008 [18] | Case study | No | 15 dogs Inclusion: epileptic seizures Exclusion: - | Gold wire implants in acupuncture points. | Clinically and with electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings, the number of seizures and seizure severity were compared before and after treatment. | There were no significant statistical differences before and after treatment in relative power or in intrahemispheric coherence in the EEG recording. However, there was a significant mean difference in seizure frequency and severity between control and treatment periods. | High |

| Hielm-Björkman et al., 2001 [19] | RCT | Yes | 38 dogs Inclusion: osteoarthritis induced by hip dysplasia | Gold wire implants at acupuncture points around the hip joints. Control: three “holes” in the skin. Both groups: meloxicam when needed. | Dogs’ locomotion, hip function and signs of pain, radiographs. Registration of meloxicam medication frequency. | No differences between the treated and control groups. | Low/moderate |

| Jæger et al., 2006 [20] | RCT | Yes | 78 dogs Inclusion: osteoarthritis induced by hip dysplasia Exclusion: No previous treatment of acupuncture | The gold implantation group had small pieces of 24-carat gold inserted through needles at five different acupuncture points, and the placebo group had the skin penetrated at five non-acupuncture points. | The owners assessed the overall effect of the treatments by answering a questionnaire, and the same veterinarian examined each dog and evaluated its degree of lameness by examining videotaped footage of it walking and trotting. | There were significantly greater improvements in mobility and greater reductions in signs of pain in the dogs treated with gold implantation than in the placebo group. | Moderate |

| Bolliger et al., 2002 [21] | RCT | Yes | 19 dogs Inclusion: hip dysplasia Exclusion: - | Gold bead implantation and superficial needle punctures (control). | Gait analysis, kinetic and kinematic analysis. Questionnaire. | No differences in kinetic and kinematic variables were seen before or one and three months after. | Low/moderate |

| Jæger et al., 2007 [22] | RCT (non blinded) | Yes, 7 dogs served as controls | 73 dogs Inclusion: osteoarthritis caused by hip dysplasia Exclusion: No previous treatment with acupuncture | In the long-term two-year follow-up study (from Jaeger et al., 2006), 66 of the 73 dogs had gold implantation and seven dogscontinued as a control group. The 32 dogs in the original placebo group had gold beads implanted and were followed for a further 18 months. | The owners assessed the overall effect of the treatments by answering a questionnaire, and the same veterinarian examined each dog and evaluated its degree of lameness by examining videotaped footage of it walking and trotting. | The pain-relieving effect of gold bead implantation observed in the blinded study continued throughout the two-year follow-up period. | High |

| Study | Study Design | Control Group | Study Sample | Intervention and Dosage | Outcome Variables | Main Results | Study Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balbueno et al., 2020 [23] | RCT | Yes | 30 dogs Inclusion: in stage B2 of myxomatous mitral valve disease Exclusion: pulmonary edema, undergoing heart treatment | Three groups of 10 dogs each. Hypotensive treatment with Crataegus oxyacantha at a potency of (1) 6cH and (2) Crataegus MT or (3) hydroalcoholic solution (placebo). | Echocardiogram, laboratory blood tests, systolic blood pressure. Follow up at 30, 60, 90, and 120 days after initiation of the therapy. | No differences between groups. Some significant differences in within- group analysis. | Low/moderate |

| Boehm, 2020 [24] | Case study | No | 10 dogs Inclusion: Atopic dermatitis Exclusion: Skin infection | Combination product Adrisin, three times a day over three weeks. | Canine atopic dermatitis lesion index, pruritus visual analog scale. | No differences over the duration of treatment. | Moderate/high |

| Neumann et al., 2011 [25] | Prospective, observational open-label cohort study | Yes, active control | 68 dogs Inclusion: osteoarthritic Exclusion: <1 year | Complex homeopathic preparation Zeel ad us.vet (one to three tablets orally per day depending on body weight) to carprofen (4 mg/kg body weight) over 56 days. | Symptomatic effectiveness, lameness, stiffness of movements, and pain on palpation were evaluated by treating veterinarians and owners. | Clinical signs OA improved significantly at all time points (days 1, 28, and 56) with both therapies. | High |

| Beceriklisoy et al., 2008 [26] | RCT | Yes, active control | 38 dogs Inclusion: Clinically pseudo-pregnant bitches | Group I: Thuja occidentalis D30 (8 globules, three times a day, per os, n = 15); Group II: Urtica urens D6 (eight globules, three times a day, per os, n = 15); Group III: naloxone (control group, 0.01 mg/kg, twice daily, s.c., n = 8). | Animals were classified as no, mild, moderate, and severe according to the clinical signs of mammary glands and behavioral signs during the study. Bitches were examined at 3–5 days intervals by means of inspection and palpation until clinical signs resolved. | Concerning mammary gland scores, treatments yielded significantly higher success rates in Group I and Group II (100% in both groups) compared to the success rate observed in Group III (37.5%). | Moderate |

| Hielm Björkman et al., 2009 [27] | RCT | Yes, one active control and one placebo | 44 dogs Inclusion: OA and hip dysplasia | Treatment: HPS Zeel ½-1 ampoule/day Active control: Carprofen 2 mg/kg twice daily Placebo: lactose capsule | Six variables: Veterinary-assessed mobility, two force plate variables, an owner-evaluated chronic pain index, and painand locomotion visual analogue scales (VASs). | When measured by dichotomous responses of ‘improved’ or ‘not improved,’ there were changes. Veterinary-assessed mobility, peak vertical force and pain VAS showed a significant difference in improved dogs per group between the treated group and the placebo group. | Low/moderate |

| Cracknell and Mills, 2008 [28] | RCT | Yes | 75 dogs Inclusion: fear response to fireworks | A homeopathicremedy based on phosphorus, rhododendron, borax, theridion, and chamomilla (6C and 30C in 20% alcohol), and a ‘control’preparation of water and 20% alcohol. | Assessment of dog’s fear severity was based on the owner’s perception of their dog’s behavior before, during, and after they completed the trial period. | There were significant improvements in the owners’ rating of 14/15 behavioral signs of fear in the placebo treatment group and all 15 behavioral signs in the homeopathic treatment group. | Moderate |

| Aboutboule, 2009 [29] | Case study | No | 15 cats Inclusion: Eosinophilic granuloma complex (EGC) | The snake remedies used were Lachesis (9 cases), Crotalus cascavella (1 case), Crotalus horridus (1), Cenchris contortrix (1), Elaps corallinus (1), Naja (1), and Vipera (1). | Diagnosis of EGC was based on the clinical observation of characteristic dermatological lesions and usually confirmed by biopsy. | 10 had good response, four dropped out and one did not respond to treatment. | High |

| Chaudhury & Varshney, 2007 [30] | Prospective study | Yes, active control | 33 dogs Inclusion: Canine babesiosis | Group A was treated with C. horridus 200C, four pills four times a day orally for 14 days and Group B with diminazene aceturate at 5 mg/kg intramuscularly single dose. All the dogs were administered 5% dextrose normal saline at 60 mL/kg intravenously for four days. | The therapeutic efficacy was evaluated using clinical score, peripheral blood smear examination, and hematological indices (Hb, PCV and TEC) on days 0, 3, 7, and 14. | Mean clinical score revealed that numbers of clinical signs reduced significantly on day 14 post therapy with both C. horridus and diminazene aceturate. The number of parasitized erythrocytes also reduced significantly after treated with C. horridus on day 14 and with diminazene aceturate on days 3, 7, and 14 from baseline. | High |

| Hill et al., 2009 [31] | Case study | No | 20 dogs Inclusion: atopic dermatitis | Individualized remedies prescribed on the basis of the dog’s cutaneous signs and constitutional characteristics. | The response to treatment was assessed by scoring the severity of pruritus from 0 to 10 on a validated scale. | In 15 cases, the owners reported no improvement. In the other five cases, the owners reported the treatment as associated with reported reductions in pruritus scores ranging from 64 to 100%. | High |

| Yaramiş et al., 2016 [32] | Case study | No | 16 horses Inclusion: stereotypic behavior | Homeopathic Ignatia and/or Gelsenium have been used for every horse according to the effects of each remedy on behavioral problem. Additionally, Stramonium, Phosphorus, Nux vomica, Pulsatilla, Hypericum, Lycopodium, Argentum nitricum, Staphysagria, Arsenicum album, Lachesis, and Thuya occidentalis were used as treatment remedies specific for each horse. | For each horse, each person on the observation team was asked to provide their impression of the pattern of stereotypic behavior at the end of each month, according to daily observations throughout the study. | By treatment survey analysis, after one-month evaluation, the symptoms of stereotypical behaviors were found to be decreased, and after two months considerable regression was detected. | High |

| Raj et al., 2020 [33] | RCT | Yes | 16 dogs Inclusion: oral papillomatosis | Homeopathic drugs in combination (Sulfur 30C, Thuja 30C, Graphites 30C, and Psorinum 30C) and placebo drug (distilled water) was administered orally twice daily for 15 days. | Dogs were clinically scored for oral lesions on days 0, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 150 after initiation of treatment. Physical examination, complete blood count, and serum biochemistry. Biopsy samples from papillomatous lesions on 0th and 7th days post-treatment. | The homeopathic treatment group showed early recovery with a significant reduction in oral lesions reflected by clinical score in comparison to placebo-treated group. | Moderate |

| Bodey et al., 2017 [34] | RCT | Yes | 40 cats Inclusion: Feline hyper-thyroidism, thyroid hormone T4 | Individual remedies by adding the sarcode thyroidinum and an appropriate individualized simillimum. The placebo was water and ethanol. | After 21 days, the T4 levels, weight (Wt), and heart rate (HR) were compared with pre-treatment values. | There were no differences in the changes seen between the two treatment arms following placebo or homeopathic treatment, or between means of each variable before and after placebo or homeopathic treatment. | Low |

| Marchiori et al., 2019 [35] | RCT | Yes | 10 dogs Inclusion: sound dogs, treated to stimulate canine immunity by modulating blood cell responses | The treated group (n = 5) received a basal diet with an additional dose of 0.5 mL/animal/day homeopathic solution (Echinacea angustifolia 6 CH, Aconitum napellus 30 CH, Veratrum album 30 CH, Pyrogenium 200 CH, Calcarea carbonica 30 CH, and Ignatia amara 30 CH), and Group C (n = 5) received only the basal diet. | The animals were weighed, and blood samples were collected for complete blood counts and serum biochemistry on days 1, 15, 30, and 45 of the experiment. | Lymphocyte counts were greater in the treated group on days 30 and 45 of the experiment. | High |

| Faulstich 2006 [36] | Case study | Yes, active control | 46 Horses Inclusion: lameness Exclusion: - | Control: Hyaluronic acid Treatment: Complex of 14 homeopathically-prepared ingredients Zeel (D8). | Clinical examination days 7, 14, and 21. At two different horse clinics. | Therapeutic effect ascertained by clinical examination. | Moderate/high |

| Cayado Robledo, 2016 [37] | Case study | No | 5 horses Inclusion: Equine laminitis | Homeopathic treatment: Aconitum 30C, Apis 15C, Arnica 7C, Belladonna 9C, Bryonia 9C, and Nux vomica 9C. Two granules of each component every hour during the day, 10 times per day for 10 days. | Variables evaluated included signs of pain, grade of lameness, digital pulse, and plasma levels of nitric oxide, nitric oxide synthase expression, carbon monoxide, and heme oxygenases. | Homeopathically-treated horses showed an obvious improvement after one day of treatment. | High |

| Leeches (Hirudotherapy) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Control Group | Study Sample | Intervention and Dosage | Outcome Variables | Main Results | Study Risk of Bias |

| Rasch, 2010 [38] | Cohort, Retrospective | No | 57 horses Inclusion: Laminitis Exclusion: NA | 112 bloodsucker applications in 57 laminitic horses. | Grading according to Obel. | Clinical improvement: 84% improved after the application of hirudotherapy. | High |

| Mesotherapy | |||||||

| Alves et al., 2018 [39] | RCT (experi-mental) | Yes, active control | 15 dogs Inclusion: chronic back pain | Control (CG; n = 5) and treatment groups (TG; n = 10). A combination of 140 mg lidocaine, 15 mg dexamethasone, and 20 mg thiocolchicoside was administered to group TG along with a 70-day course of a placebo. Carprofen was administered to Group CG for 70 days. On day 0, an intradermal injection of Ringer’s lactate was administered. | Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI) and the Hudson Visual Analogue Scale (HVAS), evaluated before treatment (T0), after 15 days (T1), and at one (T2), two (T3), three (T4), four (T5), and five (T6) months. | No differences were found in CBPI results between groups TG and CG at T0 through T3 and in T6 and T7. Differences in CBPI sections after the discontinuation of carprofen: at T4 for Pain Interference Score for Pain Severity Score and T5 for PIS and for PSS, with group TG having overall better results. Individual treatment results were considered successful in one dog of group CG, whereas in group TG success was higher. No differences were registered with the HVAS. | Moderate |

| Alves et al., 2021 [40] | Retro-spective study | Yes | 20 dogs Inclusion: back pain | 1. combination of lidocaine, dexamethasone, and tiocolchicoseide. 2. as previous with an additional traumeel LT. | The Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI) and the Hudson Visual Analogue Scale (HVAS), evaluated before treatment (T0), after 15 days (T1), and at one (T2), two (T3), three (T4), four (T5), and five (T6) months. | No differences were observed between groups. | Moderate/high |

| Mud therapy | |||||||

| Bartos et al., 2014 [41] | Case study | No | 10 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Horses were treated with mud treatment from Lake Hévíz 10 times, twice daily. | Before and after the experiment and eight weeks following, the average stride length and the longest distance between the hind and front foot during walking and trotting, and maximal flexibility of knee, hock and fetlock joints were measured. The maximal flexibility of each joint was measured with a joint protractor. | The stride length and longest distance between front and hindlimb were slightly but positively influenced after treatment. | High |

| Neural therapy (NT) | |||||||

| Bravo-Monsalvo et al., 2008 [42] | Case study | No | 18 dogs Inclusion: canine atopic dermatitis | One set given by injecting an intravenous dose of 0.1 mg/kg of a 0.7% procaine solution, followed by 10 to 25 intradermal injections of the same solution in a volume of 0.1–0.3 mL per site. Dogs were given six to 13 sets. | The dermatological condition of each patient was evaluated before and after the treatment using two scales: the pruritus visual analogue scale (PVAS) and the canine atopic dermatitis extent and severity index (CADESI). | The reduction of pruritus was statistically significant. | High |

| Eisenmenger et al., 1989 [43] | Case study | No | 60 horses Inclusion: pain syndrome in the loin and hip region. | 5 mL of a 1% solution without additives for each point; usually eight to 14 segments were infiltrated symmetrically paramedian. This infiltration was repeated each third day, four to five times. | Clinical examination | Of the 60 patients, 51 were infiltrated, of which 45 were controlled. Seven of them were no longer used for competition, and in four horses, the evaluation time after treatment was too short. Of the remaining 34 horses, 26 could be trained successfully and won several more races, while eight horses did not recover. | High |

| Sound (music) therapy | |||||||

| Kedzierski et al., 2017 [44] | RCT | Yes | 12 horses out of 60 Inclusion: Sound race horses Exclusion: - | Sixty horses were equally divided into one control group and four experimental groups; treated with music for one hour a day, music for three hours a day, massage on theday preceding a race, and daily massage during the six months of the racing season. | Heart rate (HR) and variables of heart rate variability, root mean square of successive beat-to-beat difference [RMSSD]) were measured. Salivary cortisol concentrations were measured before and after training sessions. Official general handicap and success coefficient in the racing season were considered as performance variables. | In the experimental groups, lowered HR, LF/HF, and salivary cortisol concentrations, as well as increased RMSSD, were found at various levels. It was shown that playing relaxing music for three hours a day had more positive effects on horses’ emotional state than for one hour. | High |

| Study | Study Design | Control Group | Study Sample | Intervention and Dosage | Outcome Variables | Main Results | Study Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchner et al., 2017 [45] | Case study | No | 10 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Standing on a vibration plate = control. Treatment = 15 and 25 Hz during 10 min, respectively. | Frequency, peak-to-peak displacement, and peak acceleration. Activity of m triceps, quadriceps, and longissimus dorsi was assessed with surface electromyography. Maximal body temperature at upper forelimb, thigh, and back was measured. | The 10-min vibration exercise had no significant effect. | Moderate/high |

| Halsberghe, 2017 [46] | Experi-mental single subject repeated design | 4 horses | 8 horses Inclusion: chronic lameness | 8 horses were subjected to whole-body vibration (WBV) 30 min, twice daily, for five days a week for 60 days. | Visual examination and inertial sensors (lameness locator). | No significant difference in lameness was seen after 30 or 60 days of WBV. | Moderate/high |

| Mackechnie-Guire et al., 2018 [47] | RCT | Yes | 30 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Treatment = 20 min cycloidal vibration therapy. Control = no treatment. | Inertial sensors, epaxial muscle dimension by a flexible curved ruler. | Within groups: there was a significant increase in muscle dimension and in inertial measurement unit registrations. No comparisons were made between groups. | Moderate |

| Carstanjen et al., 2013 [48] | Case study | No | 7 horses Inclusion: sound horses | WBV treatment for 10 min and 15–21 HX. | Clinical variables and venous blood samples before and after treatment. | Decrease in serum cortisol and creatin-kinase values. | High |

| Santos et al., 2017 [49] | Case study | No | 10 dogs Inclusion: sound dogs | WBV exercise with daily sessions at 30 Hz for five minutes, followed by 50 Hz for five minutes, and finally 30 Hz for five minutes over five days. Velocity 12–40 m/s2 and amplitude 1.7–2.5 mm. | Complete blood count and serum biochemistry. | The treatment did not cause adverse effects on hematology and serum biochemistry in healthy adult dogs. | Moderate/high |

| Nowlin et al., 2018 [50] | RCT | Yes | 6 horses Inclusion: sound | Treated horses stood on a platform vibrating at 50 Hz for 30 min, and control horses stood on an adjacent platform that was not turned on for 30 min. | Lameness score, joint range of motion, and stride length were assessed visually. Horses were re-evaluated acutely after one initial 30-min treatment and again after three weeks, with treatments repeated daily (five days per week). | Findings suggest no differences from pre- to post-treatment between vibration therapy (VT) and control (CO) groups in any variables measured. | Moderate |

| Hyatt et al., 2017 [51] | RCT | Yes | 20 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Treatment on a vibration plate at 50 Hz for 30 min, five days a week. Control = 30 min turnout. | Serum blood analysis | Gamma-glutamyltransferase showed a greater reduction in the control group compared to the treated group. Creatinkinase showed a reduced value in the control group and increased value in the treated group. | Low/moderate |

| Maher et al., 2017 [52] | RCT | Yes | 11 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Treatment at 50 Hz for 45 min, five days a week. Both groups = exercise on a mechanical panel exerciser. | Radiographs were taken at −28, 0, and 28 days to assess bone mineral content. Heart rate and stride length at day 23. | No significant differences were found. | Moderate |

| Hulak et al., 2015 [53] | RCT | Yes | 12 horses Inclusion: sound horses | Treatment at 50 Hz for 45 min, five days a week. Controls = exercise on a mechanical panel exerciser. | Radiographs were taken at −28, 0, and 28 days to assess bone mineral content. | No significant differences were found. | Moderate |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bergh, A.; Lund, I.; Boström, A.; Hyytiäinen, H.; Asplund, K. A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”. Animals 2021, 11, 3356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123356

Bergh A, Lund I, Boström A, Hyytiäinen H, Asplund K. A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”. Animals. 2021; 11(12):3356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123356

Chicago/Turabian StyleBergh, Anna, Iréne Lund, Anna Boström, Heli Hyytiäinen, and Kjell Asplund. 2021. "A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”" Animals 11, no. 12: 3356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123356

APA StyleBergh, A., Lund, I., Boström, A., Hyytiäinen, H., & Asplund, K. (2021). A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine: “Miscellaneous Therapies”. Animals, 11(12), 3356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11123356