The Effects of Hotel Employees’ Attitude Toward the Use of AI on Customer Orientation: The Role of Usage Attitudes and Proactive Personality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

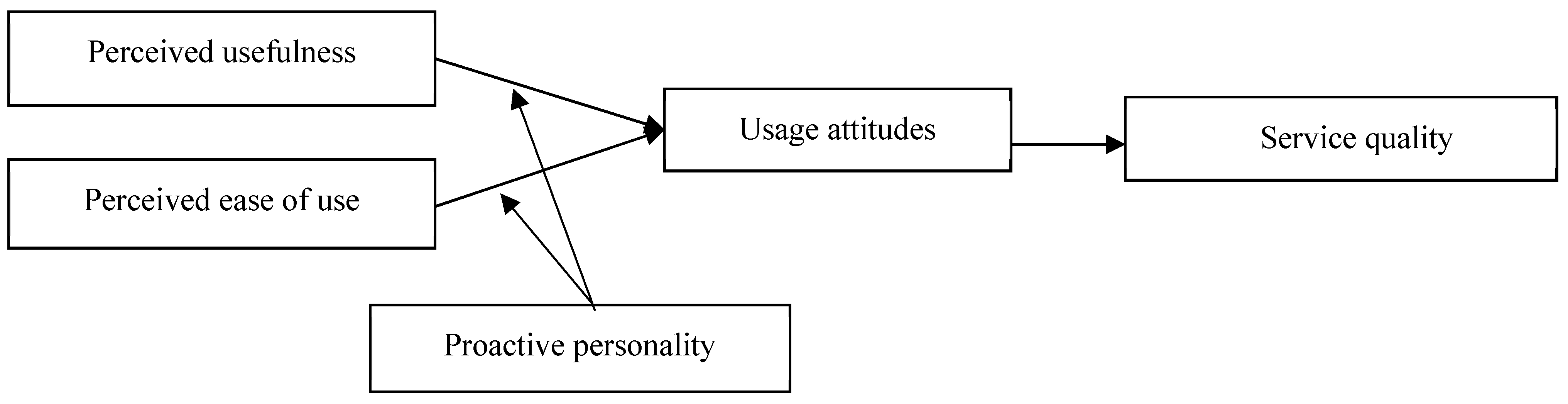

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use in Relation to Customer Orientation

2.3. The Perception of Usefulness and Ease of Use Is Associated with the Attitude Toward Usage

2.4. The Attitude Toward Usage and Customer Orientation

2.5. The Mediating Role of Usage Attitude

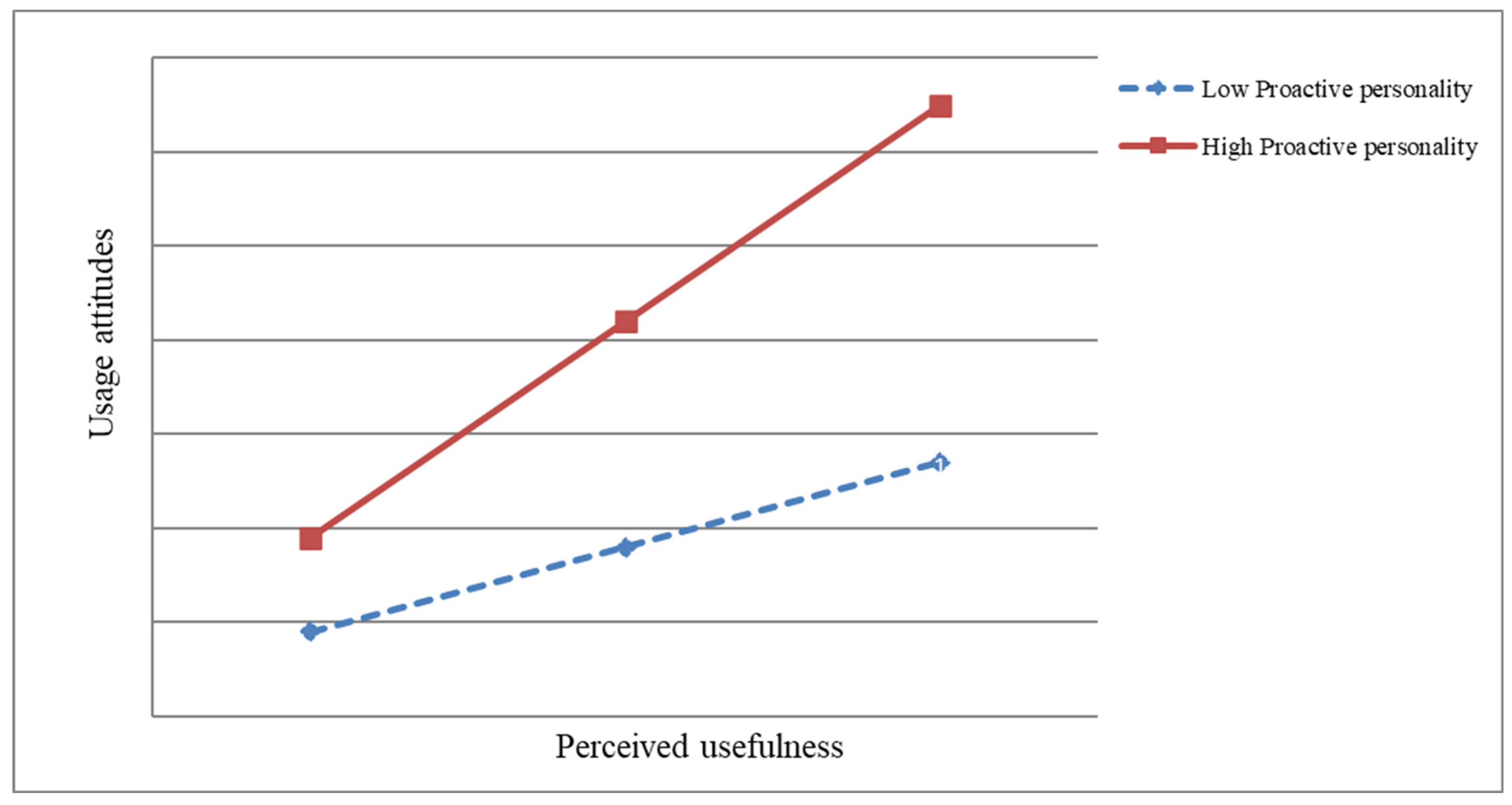

2.6. The Moderating Role of Proactive Personality

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Perceived Usefulness

3.2.2. Perceived Ease of Use

3.2.3. Attitude Toward Usage

3.2.4. Proactive Personality

3.2.5. Customer Orientation

3.2.6. Control Variables

4. Result

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Items measuring proactive personality

- In order to improve my performance, I often perform tasks that are outside the scope of my job.

- If I see something I don’t like, I get over it.

- I feel very happy when the ideas I come up with become reality.

- I am always looking for new ways to improve my life.

- I am always looking for better ways to do things.

- I am willing to believe in my ideas, even against the opposition of others.

- Items measuring perceived ease of use

- I find it easy to get the hotel technology to do what I want it to do.

- Learning to operate the hotel technology is easy for me.

- Overall, I find the hotel technology easy to use.

- It is easy for me to remember how to perform tasks using hotel technology.

- Usage of the hotel technology is understandable.

- Items measuring perceived usefulness

- Using hotel technology increases my productivity.

- Using hotel technology enhances my effectiveness on the job.

- Overall, I find hotel technology useful in my job.

- Using hotel technology makes it easier to do my job.

- Hotel technology enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly.

- Using hotel technology improves my job performance.

- Items measuring usage attitude

- All things considered, using AI is a good idea

- All things considered, using AI is advisable

- All things considered, using AI is pleasant

- I enjoy using AI

- Items measuring customer orientation

- I am very passionate about helping customers.

- I am always proactive and enthusiastic with my customers.

References

- Al-Ababneh, M. M. (2016). Employees’ perspectives of service quality in hotels. Research in Hospitality Management, 6(2), 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C., Camarero, C., & San Jose, R. (2014). Public employee acceptance of new technological processes: The case of an internal call centre. Public Management Review, 16(6), 852–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskaran, S., Lay, H. S., Ming, B. S., & Mahadi, N. (2020). Technology adoption and employee’s job performance: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics & Management Science, 9(1), 78–105. [Google Scholar]

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2021). Frontline robots in tourism and hospitality: Service enhancement or cost reduction? Electronic Markets, 31(3), 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldona, S., Schwartz, Z., & Zhang, X. (2018). Evaluating hotel guest technologies: Does home matter? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(5), 2327–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S. E., Chu, L., Lee, H. H., Yang, C. C., Lin, F. H., Yang, P. L., Wang, T. M., & Yeh, S. L. (2019). Age difference in perceived ease of use, curiosity, and implicit negative attitude toward robots. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction (THRI), 8(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y., Choi, M., Oh, M., & Kim, S. (2020). Service robots in hotels: Understanding the service quality perceptions of human-robot interaction. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(6), 613–635. [Google Scholar]

- Crant, J. M., & Bateman, T. S. (2000). Charismatic leadership viewed from above: The impact of proactive personality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J. M., Hu, J., & Jiang, K. (2016). Proactive personality: A twenty-year review. In Proactivity at work (pp. 211–243). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personen Psychology, 58(4), 859–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Moraleda, L., Díaz-Pérez, P., Orea-Giner, A., Muñoz-Mazón, A., & Villacé-Molinero, T. (2020). Interaction between hotel service robots and humans: A hotel-specific Service Robot Acceptance Model (sRAM). Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B., Jr., & Marler, L. E. (2009). Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R. J., & Karsh, B.-T. (2010). The technology acceptance model: Its past and its future in health care. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43(1), 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S., Webster, C., & Garenko, A. (2018a). Young Russian adults’ attitudes towards the potential use of robots in hotels. Technology in Society, 55, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S., Webster, C., & Seyyedi, P. (2018b). Consumers’ attitudes towards the introduction of robots in accommodation establishments. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 66(3), 302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., & Qu, H. (2014). Travelers’ behavioral intention toward hotel self-service kiosks usage. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(2), 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S., Kim, J., Badu-Baiden, F., Giroux, M., & Choi, Y. (2021). Preference for robot service or human service in hotels? Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y., Hon, A. H. Y., & Crant, J. M. (2009). Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W. R., & He, J. (2006). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Legris, P., Ingham, J., & Collerette, P. (2003). Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 40(3), 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. J., Bonn, M. A., & Ye, B. H. (2019). Hotel employee’s artificial intelligence and robotics awareness and its impact on turnover intention: The moderating roles of perceived organizational support and competitive psychological climate. Tourism Management, 73, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M., Wu, T. J., Wu, Y. J., & Goh, M. (2023a). Systematic literature review of human–machine collaboration in organizations using bibliometric analysis. Management Decision, 61(10), 2920–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M., Zhang, L. X., & Mao, M. Y. (2025). How does human-AI interaction affect employees’ workplace procrastination? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 212, 123951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M., Zhang, R.-X., Wu, T.-J., & Mao, M. (2024). How does work autonomy in human-robot collaboration affect hotel employees’ work and health outcomes? Role of job insecurity and person-job fit. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 117, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M., Zhang, X. F., Zhang, L. X., & Zhang, R. X. (2023b). Customer incivility and emotional labor: The mediating role of dualistic work passion and the moderating role of conscientiousness. Current Psychology, 42(2), 32324–32337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q., Lin, M., & Wu, X. (2016). The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and performance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tourism Management, 52, 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Lukanova, G., & Ilieva, G. (2019). Robots, artificial intelligence, and service automation in hotels. In Robots, artificial intelligence, and service automation in travel, tourism and hospitality (pp. 157–183). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J. M., Vu, H. Q., Li, G., & Law, R. (2021). Understanding service attributes of robot hotels: A sentiment analysis of customer online reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 98, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the Big Five to motivation to learn and development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N., & Granić, A. (2015). Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, B. W., Guay, R. P., Colbert, A. E., & Stewart, G. L. (2019). Proactive personality and proactive behaviour: Perspectives on person–situation interactions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(1), 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menant, L., Gilibert, D., & Sauvezon, C. (2021). The application of acceptance models to human resource information systems: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 659421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naneva, S., Sarda Gou, M., Webb, T. L., & Prescott, T. J. (2020). A systematic review of attitudes, anxiety, acceptance, and trust towards social robots. International Journal of Social Robotics, 12(6), 1179–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., & Colby, C. L. (2015). An updated and streamlined technology readiness index: TRI 2.0. Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Said, N., Ben Mansour, K., Bahri-Ammari, N., Yousaf, A., & Mishra, A. (2023). Customer acceptance of humanoid service robots in hotels: Moderating roles of service voluntariness and culture. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36, 1844–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K. H., & Lee, J. H. (2021). The emergence of service robots at restaurants: Integrating trust, perceived risk, and satisfaction. Sustainability, 13(8), 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Lee, P. C., Law, R., & Hyun, S. S. (2020). An investigation of the moderating roles of current job position level and hotel work experience between technology readiness and technology acceptance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (1996). A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decision Sciences, 27(3), 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J., Patterson, P. G., Kunz, W. H., Gruber, T., Lu, V. N., Paluch, S., & Martins, A. (2018). Brave new world: Service robots in the frontline. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. J., Li, J. M., Wang, Y. S., & Zhang, R. X. (2023a). The dualistic model of passion and the service quality of five-star hotel employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 113, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T. J., Yuan, K. S., & Yen, D. C. (2023b). Leader-member exchange, turnover intention and presenteeism–the moderated mediating effect of perceived organizational support. Current Psychology, 42(6), 4873–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. J., Zhang, R. X., & Li, J. M. (2024). How does emotional labor influence restaurant employees’ service quality during COVID-19? The roles of work fatigue and supervisor–subordinate Guanxi. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-X., Li, J.-M., Wang, L.-L., Mao, M.-Y., & Zhang, R.-X. (2023). How does the usage of robots in hotels affect employees’ turnover intention? A double-edged sword study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 57, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | NFI | IFI | TLI | RFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-factor model (1+2+3+4+5) | 6.980 | 0.116 | 0.559 | 0.516 | 0.523 | 0.561 | 0.533 | 0.494 |

| Two-factor model (1+2+3+4,5) | 5.297 | 0.098 | 0.684 | 0.602 | 0.639 | 0.685 | 0.664 | 0.616 |

| Three-factor model (1+2+3,4,5) | 3.865 | 0.080 | 0.790 | 0.683 | 0.737 | 0.791 | 0.776 | 0.720 |

| Four-factor model (1+2,3,4,5) | 2.416 | 0.056 | 0.897 | 0.801 | 0.837 | 0.897 | 0.889 | 0.825 |

| Five-factor model (1,2,3,4,5) | 1.133 | 0.017 | 0.990 | 0.928 | 0.924 | 0.990 | 0.990 | 0.918 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.47 | 0.50 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 29.57 | 5.59 | 0.06 | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Education Level | 4.35 | 1.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Years of Work Experience | 6.36 | 4.90 | 0.06 | 0.94 *** | −0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Proactive personality | 3.76 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Perceived Ease of Use | 2.18 | 0.90 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.29 *** | 1 | |||

| 7. Perceived Usefulness | 3.65 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.31 *** | 0.17 *** | 1 | ||

| 8. Usage Attitude | 3.63 | 1.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.29 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.30 *** | 1 | |

| 9. Customer orientation | 3.93 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.32 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.28 *** | 1 |

| Variable | Item | Factor Loadings | Average Variance Extracted | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive personality | A1 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.94 |

| A2 | 0.82 | |||

| A3 | 0.89 | |||

| A4 | 0.81 | |||

| A5 | 0.82 | |||

| A6 | 0.88 | |||

| Perceived ease of use | B1 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.95 |

| B2 | 0.87 | |||

| B3 | 0.91 | |||

| B4 | 0.89 | |||

| B5 | 0.93 | |||

| Perceived usefulness | C1 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.93 |

| C2 | 0.86 | |||

| C3 | 0.83 | |||

| C4 | 0.91 | |||

| C5 | 0.79 | |||

| C6 | 0.76 | |||

| Usage attitude | D1 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.91 |

| D2 | 0.81 | |||

| D3 | 0.90 | |||

| D4 | 0.82 | |||

| Customer orientation | E1 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| E2 | 0.86 |

| Model | Customer Orientation | Usage Attitude | Customer Orientation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Education Level | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Years of Work Experience | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.27 *** | 0.05 | 0.30 *** | 0.05 | 0.23 *** | 0.05 |

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.30 *** | 0.06 | 0.39 *** | 0.07 | 0.25 *** | 0.06 |

| Usage Attitude | 0.12 ** | 0.04 | ||||

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |||

| Model | M1 | M2 | M3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Education Level | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Gender | −0.11 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.10 |

| Age | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Years of Work Experience | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.37 *** | 0.08 | 0.32 *** | 0.08 | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.35 *** | 0.06 | 0.27 *** | 0.06 | ||

| Proactive Personality | 0.26 *** | 0.06 | 0.24 *** | 0.06 | ||

| Int1 | 0.14 * | 0.07 | ||||

| Int2 | 0.22 *** | 0.06 | ||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.18 | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, P.; Hou, Y. The Effects of Hotel Employees’ Attitude Toward the Use of AI on Customer Orientation: The Role of Usage Attitudes and Proactive Personality. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020127

Wang P, Hou Y. The Effects of Hotel Employees’ Attitude Toward the Use of AI on Customer Orientation: The Role of Usage Attitudes and Proactive Personality. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020127

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Peng, and Yong Hou. 2025. "The Effects of Hotel Employees’ Attitude Toward the Use of AI on Customer Orientation: The Role of Usage Attitudes and Proactive Personality" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020127

APA StyleWang, P., & Hou, Y. (2025). The Effects of Hotel Employees’ Attitude Toward the Use of AI on Customer Orientation: The Role of Usage Attitudes and Proactive Personality. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020127