Evaluating University Attributes and Their Influence on Students’ Attitudes: The Mediating Role of Social Responsibility Communication

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and the Theoretical Framework

2.1. UAE Higher Education

2.2. University Attributes

2.3. Students’ Attitudes

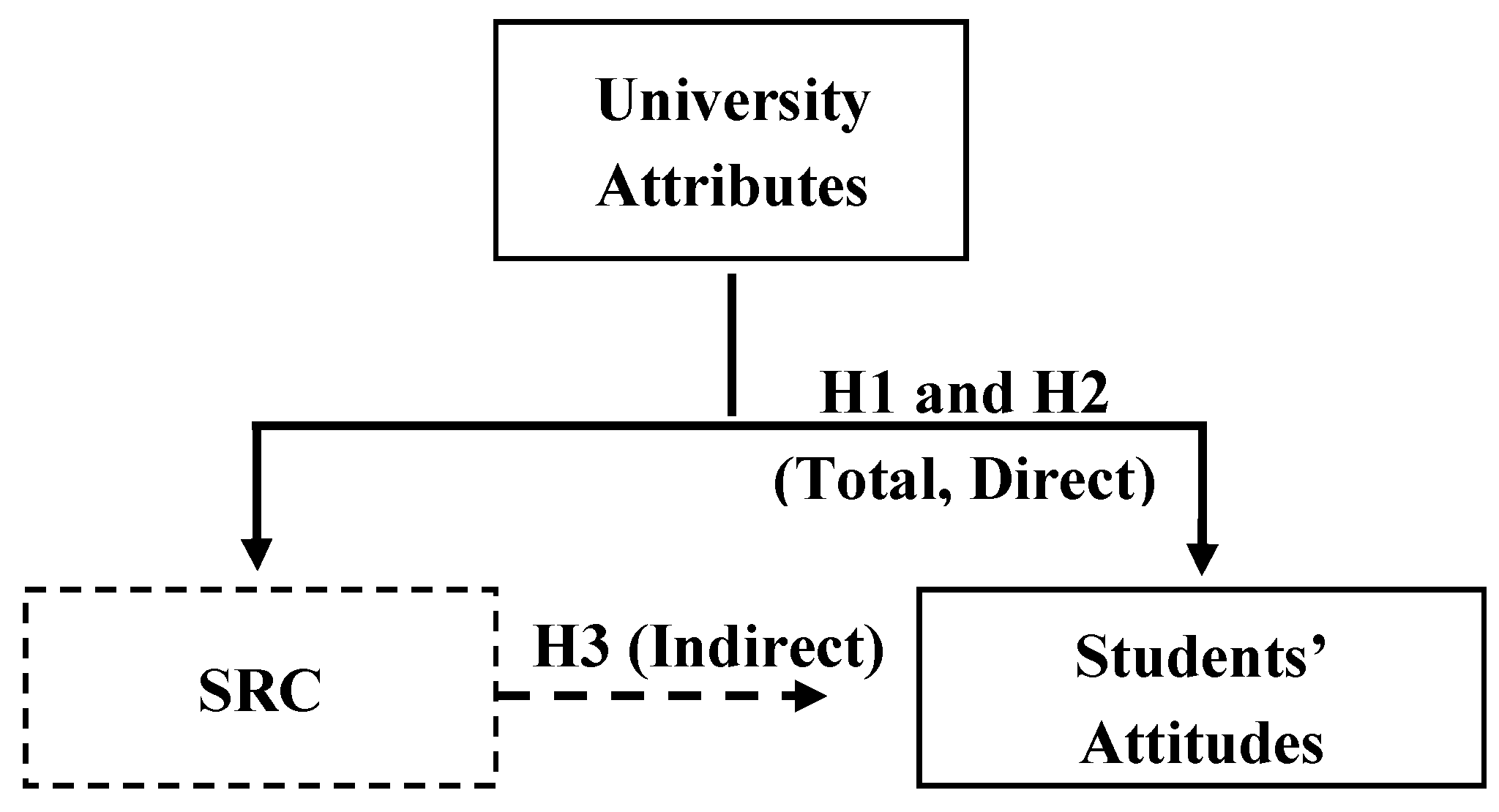

2.4. The Mediator Role of SRC

3. Method

3.1. The Sampling

3.2. Questionnaire and Measures

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Demographic Profile

| Category | N | % | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Level of study | ||||

| Male | 42 | 35.0 | Undergraduate | 114 | 95.0 |

| Female | 78 | 65.0 | Postgraduate | 6 | 5.0 |

| Age | Academic Year | ||||

| 17–20 | 53 | 44.2 | First Year | 40 | 33 |

| 21–24 | 47 | 39.2 | Second Year | 17 | 14 |

| 25–30 | 14 | 11.7 | Third Year | 38 | 32 |

| 31+ | 6 | 5.0 | Fourth Year | 23 | 19 |

| College | Fifth Year | 2 | 2 | ||

| Business Administration | 65 | 55.8 | |||

| Engineering and Information Technology | 29 | 24.2 | |||

| Dentistry | 11 | 9.2 | |||

| Architecture Art and Design | 7 | 5.8 | |||

| Mass Communication | 4 | 3.3 | |||

| Pharmacy and Health Sciences | 2 | 1.7 | |||

4.2. The University’s Attributes

| Construct | Code | Statement | Factor Loading (FL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education Cost M * = 4.10, SD = 1.07 | EC1 | The cost and tuition fee are reasonable | 0.863 |

| EC2 | The flexibility of payment time | 0.844 | |

| EC3 | The availability of financial aid | 0.726 | |

| EC4 | The flexible tuition approach such as pay per credit hour | 0.778 | |

| Employment Opportunities M = 4.00, SD = 1.02 | EO1 | Rate of job prospects for the graduates | 0.724 |

| EO2 | Recognised and positive perception of quality in the market | 0.807 | |

| EO3 | International recognition of quality students and higher rate of employability globally | 0.818 | |

| EO4 | AU offers employability services (career planning, work experience, placements, graduate jobs, etc.) | 0.688 | |

| Physical Aspects, Facilities and Resources M = 3.99, SD = 1.03 | PA1 | Location of the university | 0.676 |

| PA2 | The university campus design | 0.725 | |

| PA3 | Availability of necessary resources (e.g., labs and library, etc.) | 0.649 | |

| PA4 | Availability of healthcare services, canteen | 0.795 | |

| PA5 | Availability of accommodation | 0.896 | |

| PA6 | Availability of extracurricular activities and facilities (sport, recreations, etc.) | 0.612 | |

| University’s Image M = 3.83, SD = 0.979 | UI1 | International ranking | 0.781 |

| UI2 | QS start rating | 0.728 | |

| UI3 | National ranking | 0.620 | |

| UI4 | University offers the course I want to study | 0.550 | |

| UI5 | Faculty members are highly qualified and experienced | 0.425 | |

| UI6 | Countries/institutions of faculty members professionalism and degrees | 0.919 | |

| UI7 | Awards the university received in research | 0.651 |

4.3. Students’ Attitudes

| Construct | Code | Statement | Factor Loading (FL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional Commitment M = 3.62, SD = 0.95 | IC1 | I am aware of and believe in the AU’s goals and values. | 0.920 |

| IC2 | I am proud to become a student of AU. | 0.951 | |

| IC3 | I am willing to exert efforts on behalf of AU (volunteering, recruitment, testimonials). | 0.770 | |

| IC4 | I promote AU to my friends as a great university to study in. | 0.840 | |

| IC5 | I would have stopped my education at AU. | 0.047 | |

| Degree Commitment M = 3.39, SD = 0.96 | DC1 | I believe in the value of my degree at AU. | 0.793 |

| DC2 | I believe in the value of my degree for my career goals and aspirations at AU. | 0.016 | |

| DC3 | I am happy with AU, but I want to withdraw from the programme. | 0.802 | |

| Social Integration M = 3.52, SD = 1.06 | SI1 | My interpersonal relationships with other students have had a positive influence on my sense of belonging. | 0.890 |

| SI2 | Students at AU have values and attitudes similar to mine. | 0.918 | |

| SI3 | My interactions with faculty have had a positive influence on my sense of belonging. | 0.821 | |

| SI4 | My overall social life experience at AU is satisfying. | 0.803 | |

| Academic Integration M = 3.62, SD = 0.95 | AI1 | I am well informed about all aspects of university life, including academics, campus events, and tuition costs. | 0.803 |

| AI2 | Since joining AU, I have developed a sense of intellectual growth and interest in new ideas. | 0.938 | |

| AI3 | The curriculum and instruction contribute to my personal goals. | 0.918 | |

| AI4 | My current financial situation does not allow me to handle the university cost. | 0.584 |

4.4. Correlation Analysis

4.5. Mediation Analysis of the Effect of University Attributes on Students’ Attitudes through SRC

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Attributes | Importance | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| University’s Image | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Physical aspects, facilities and resources | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Cost of education | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Employment opportunities | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

References

- Abrams, Dana R. 2022. Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Higher Education: Exploring DEI Elements across Institutions. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison, Claire, Rowena Harper, Negin Mirriahi, and Cally Guerin. 2020. Tensions for educational developers in the digital university: Developing the person, developing the product. Higher Education Research & Development 39: 171–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajman University. 2022. Ajman University Enrolled Students. Ajman University. Available online: https://rb.gy/iufdd2 (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Alcaide-Pulido, Purificación, Helen O’Sullivan, and Chris Chapleo. 2021. The application of an innovative model to measure university brand image. Differences between English, Spanish and Portuguese undergraduate students. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 34: 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledo-Ruiz, María Dolores, Eva Martínez-Caro, and José Manuel Santos-Jaén. 2021. The influence of corporate social responsibility on students’ emotional appeal in the HEIs: The mediating effect of reputation and corporate image. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 578–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Choudhury, Rehnuma, Roger Bennett, and Sharmila Savani. 2009. University marketing directors’ views on the components of a university brand. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 6: 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, Radhi, Mitchell Parkes, and Rachael Adlington. 2017. Using WhatsApp in EFL instruction with Saudi Arabian university students. Arab World English Journal 8: 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankit, Ahmed, and EL-Sakran Tharwat. 2020. Corporate social responsibility: Reflections on universities in the United Arab Emirates. In Leadership Strategies for Promoting Social Responsibility in Higher Education (Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, Volume 24). Edited by Enakshi Sengupta, Patrick Blessinger and Craig Mahoney. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, Sanaa. 2020. Quality higher education is the foundation of a knowledge society: Where does the UAE stand? Quality in Higher Education 26: 209–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversano, Natalia, Ferdinando Di Carlo, Giuseppe Sannino, Paolo Tartaglia Polcini, and Rosa Lombardi. 2020. Corporate social responsibility, stakeholder engagement, and universities: New evidence from the Italian scenario. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1892–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, Rajeev, Aaron Ahuvia, and Richard P. Bagozzi. 2012. Brand love. Journal of Marketing 76: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, Robin, Brian J. Bowe, and Lucinda D. Davenport. 2019. Accrediting council on education in journalism and mass communications accreditation: Quality or compliance? Journalism Studies 20: 1458–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordalo, Pedro, Nicola Gennaioli, and Andrei Shleifer. 2012. Salience theory of choice under risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127: 1243–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, Nicola, Richard Kemp, and Rosemary Snelgar. 2009. SPSS for Psychologists, 4th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, Mark. 2020. Higher education marketing communications in the digital era. In Strategic Marketing of Higher Education in Africa. Edited by Emmanuel Mogaji, Felix Maringe and Robert Ebo Hinson. London: Routledge, pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie, Garry, and Peter Wolnizer. 1999. Unravelling the rhetoric about the financial reporting of public collections as assets: A response to Micallef and Peirson. Australian Accounting Review 9: 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Cecilia Ka Yuk, and Siaw Wee Chen. 2023. Student partnership in assessment in higher education: A systematic review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 48: 1402–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Soobin, and Yun-Kyung Cha. 2021. Integration policy in education and immigrant students’ patriotic pride in host countries: A cross-national analysis of 24 European countries. International Journal of Inclusive Education 25: 812–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Tony, Constantino Stavros, and Angela R. Dobele. 2023. The impact of social media evolution on practitioner-stakeholder relationships in brand management. Journal of Product & Brand Management 32: 1173–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, Dan-Cristian, Brândșua Mariana Bejan, and Vasile Dinu. 2019. How sustainability oriented is generation Z in retail? A literature review. Transformations in Business & Economics 18: 140–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, Mai Thi Ngoc, and Anthony Thorpe. 2015. What factors influence Vietnamese students’ choice of university? International Journal of Educational Management 29: 666–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destin, Mesmin, and Ryan C. Svoboda. 2018. Costs on the mind: The influence of the financial burden of college on academic performance and cognitive functioning. Research in Higher Education 59: 302–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Paulo O., Helena B. Alves, and Mário B. Raposo. 2010. Understanding university image: A structural equation model approach. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 7: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, Husain, and Hyunjin Seo. 2019. Visual public relations in Middle Eastern higher education: Content analysis of Twitter images. Media Watch 10: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alfy, Shahira, and Abdulai Abukari. 2020. Revisiting perceived service quality in higher education: Uncovering service quality dimensions for postgraduate students. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 30: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Refae, Ghaleb, Abdoulaye Kaba, and Shorouq Eletter. 2021. The impact of demographic characteristics on academic performance: Face-to-face learning versus distance learning implemented to prevent the spread of Covid-19. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 22: 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elareshi, Mokhtar, and Ayman Bajnaid. 2019. Libyan PR participants’ perceptions of and motivations for studying PR in Libya. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations 21: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, Ismail, Sevtap Unal, and Fulya Acikgoz. 2021. What affects university image and students’ supportive attitudes: The 4Q model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 33: 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashami, Ashkan Mirzay. 2020. Gender differences in the use of social media: Australian postgraduate students’ evidence. International Journal of Social Science and Human Research 3: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajoš, Boris. 2017. Student motivation for enrolling in public relations studies and their perception of the public relations profession and study in Croatia. Journal of Innovative Business and Management 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, Mohamed Ashmel Mohamed, Issam Tlemsani, Robin Matthews, Rachel Mason-Jones, and Vera Ndrecaj. 2022. Emergent strategy in higher education: Postmodern digital and the future? Administrative Sciences 12: 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Andrew R., Madeleine J. Henley, Nicholas J. Foster, Amanda L. Peiffer, Matthew S. Beyersdorf, Kevon D. Stanford, Steven M. Sturlis, Brian M. Linhares, Zachary B. Hill, James A. Wells, and et al. 2018. Conservation of coactivator engagement mechanism enables small-molecule allosteric modulators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 8960–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, Adboulaye, and Raed Said. 2014. Bridging the digital divide through ICT: A comparative study of countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, ASEAN and other Arab countries. Information Development 30: 358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, Vikrant, and Nurmahmud Ali. 2020. University reputation, brand attachment and brand personality as antecedents of student loyalty: A study in higher education context. Corporate Reputation Review 23: 254–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnula, Marianne, and Netta Iivari. 2019. Empowered to make a change: Guidelines for empowering the young generation in and through digital technology design. The FabLearn Europe 16: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, George D. 2005. Student engagement in the first year of college. In Challenging and Supporting the First-Year Student: A Handbook for Improving the First Year of College. Edited by Upcraft M. Lee, John N. Gardner and Betsy Overman Barefoot. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 86–107. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, Khawaja Fawad, Louise Bunce, and Muhammad Shakil Ahmad. 2021. How can universities improve student loyalty? The roles of university social responsibility, service quality, and “customer” satisfaction and trust. International Journal of Educational Management 35: 815–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Youngah, Wayne Wanta, and Hyunmin Lee. 2015. Resource-based public relations efforts for university reputation from an agenda-building and agenda-setting perspective. Corporate Reputation Review 18: 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Simon A., and Ning-Kuang Chuang. 2010. Demographic factors influencing selection of an ideal graduate institution: A literature review with recommendations for implementation. College Student Journal 44: 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann, Walter. 1922. Public Opinion. San Diego: Harcort Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Chung-Kwan, and Ka-Yan Liu. 2022. How to sustain quality education in a fully online environment: A qualitative study of students’ perceptions and suggestions. Sustainability 14: 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, Jan. 2021. The intersection of class, race, gender and generation in shaping Latinas’ sport experiences. Sociological Spectrum 41: 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, Emmanuel, Josue Kuika Watat, Sunday Adewale Olaleye, and Dandison Ukpabi. 2021. Recruit, retain and report: UK universities’ strategic communication with stakeholders on Twitter. In Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age. Edited by Camilleri Mark Anthony. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orodho, John Aluko, Peter Ndirangu Waweru, Miriam Ndichu, and Ruth Nthinguri. 2013. Basic education in Kenya: Focus on strategies applied to cope with school-based challenges inhibiting effective implementation of curriculum. International Journal of Education and Research 1: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Özturgut, Osman. 2017. Internationalization for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice 17: 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pallot, June. 1990. The nature of public assets: A response to Mautz. Accounting Horizons 4: 79. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, Swati, Satyendra C. Pandey, Andrea Bennett, and Xiaoguang Tian. 2019. University brand image as competitive advantage: A two-country study. International Journal of Educational Management 33: 234–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Ashley N., Karly Sarita Ford, and Leandra Cate. 2022. Digital formations of racial understandings: How university websites are contributing to the ‘Two or More Races’ conversation. Race Ethnicity and Education 25: 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar, Musa, Paul Trapp, Tulay Girard, and Thomas E. Boyt. 2014. University brand equity: An empirical investigation of its dimensions. International Journal of Educational Management 28: 616–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, Nathaniel, Samuel Onasanya, and Charles Olumorin. 2018. Perceived usefulness, ease of use and adequacy of use of mobile technologies by Nigerian university lecturers. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT) 14: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, Fatimah Mulya, and Lulud Oktaviani. 2021. Undergraduate students’ views on the use of online learning platform during COVID-19 pandemic. Teknosastik Journal 19: 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, Walesska, Amparo Cervera-Taulet, and Walter Wymer. 2021. The influence of university brand image, satisfaction, and university identification on alumni WOM intentions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 33: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepetis, Anastasios, Aspasia Goula, Niki Kyriakidou, Fotios Rizos, and Marilena G. Sanida. 2020. Education for the sustainable development and corporate social responsibility in higher education institutions (HEIS): Evidence from Greece. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies 8: 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, Savera, and Ayesha Ashfaq. 2018. Strategic political communication, public relations, reputation management & relationship cultivation through social media. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 2: 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shammot, Marwan M. 2011. Factors affecting the Jordanian students’ selection decision among private universities. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly 2: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner, Michael, and Philip Noden. 2015. ‘Why are you applying there?’: ‘race’, class and the construction of higher education ‘choice’ in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sociology of Education 36: 1170–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramesh, Krishnamurthy, Chew Wee Ng, Soh Ting Ting, and Luo Wanyin. 2007. Corporate social responsibility and public relations. In The Debate over Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Steven K. May, George Cheney and Juliet Roper. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 119–34. [Google Scholar]

- Symaco, Lorraine Pe, and Meng Yew Tee. 2019. Social responsibility and engagement in higher education: Case of the ASEAN. International Journal of Educational Development 66: 184–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, Khalaf, Charles Self, and Zuhair Tahat. 2019. An examination of curricula in Middle Eastern journalism schools in light of suggested model curricula. Jordan Journal of Social Sciences 12: 10350. [Google Scholar]

- Temizer, Leyla, and Ali Turkyilmaz. 2012. Implementation of student satisfaction index model in higher education institutions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 46: 3802–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Ly Thi, Jisun Jung, Lisa Unangst, and Stephen Marshall. 2023. New developments in internationalisation of higher education. Higher Education Research & Development 42: 1033–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Ted. 2012. Global Warming Could Lead to Cannibalism. San Francisco: The Wayback Machine. [Google Scholar]

- Veciana, José Ma, Marinés Aponte, and David Urbano. 2005. University students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship: A two countries comparison. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 1: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, Sophia Charlotte, Daniel Vogler, Silke Fürst, Mike S. Schäfer, and Isabel Sörensen. 2023. Role conceptions of university communicators: A segmentation analysis of communication practitioners in higher education institutions. Public Relations Review 49: 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, Stephen. 2020. The positioning and competitive strategies of higher education institutions in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Educational Management 34: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Shurong, and Junxia Song. 2020. Students’ perceptions of a learning support initiative for b-MOOCs. International Journal of Emerging Technologies (IJET) 15: 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. University image | 1.0 | ||||||||

| 2. Social responsibility communication | 0.623 ** | 1.0 | |||||||

| 3. Physical aspects, facilities and resources | 0.687 ** | 0.646 ** | 1.0 | ||||||

| 4. Education cost | 0.400 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.551 ** | 1.0 | |||||

| 5. Employment opportunities | 0.652 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.556 ** | 0.565 ** | 1.0 | ||||

| 6. Institutional commitment | 0.063 | 0.113 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.068 | 1.0 | |||

| 7. Degree commitment | 0.028 | 0.086 | 0.019 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.764 ** | 1.0 | ||

| 8. Social integration | 0.109 | 0.121 | 0.128 | 0.103 | 0.080 | 0.817 ** | 0.695 ** | 1.0 | |

| 9. Academic integration | 0.100 | 0.142 | 0.107 | 0.062 | 0.076 | 0.799 ** | 0.674 ** | 0.791 ** | 1.0 |

| Model Summary: Outcome Variable: SRC | Model | R | R2 | MSE | f-Value | df1 | df2 | p-Value |

| Constant | 0.6835 | 0.6835 | 0.2957 | 103.4454 | 1.0000 | 118.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Model 1 | coeff | se | t-value | p-value | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Constant | 0.6756 | 0.3112 | 2.1713 | 0.0319 | 0.0594 | 1.2919 | ||

| University attributes | 0.7852 | 0.0772 | 10.1708 | 0.0000 | 0.6323 | 0.9381 | ||

| Model Summary: Outcome Variable: Students’ Attitudes | Model | R | R2 | MSE | f-Value | df1 | df2 | p-Value |

| Constant | 0.1292 | 0.0167 | 0.7883 | 0.9926 | 2.0000 | 117.0000 | 0.3737 | |

| Model 2 | coeff | se | t-value | p-value | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Constant | 3.0107 | 0.5181 | 5.8108 | 0.0000 | 1.9846 | 4.0368 | ||

| Students’ attitudes | −0.0330 | 0.1727 | −0.1911 | 0.8487 | −0.3750 | 0.3090 | ||

| SRC | 0.1728 | 0.1503 | 1.1497 | 0.2526 | −0.1249 | 0.4705 | ||

| Model Summary: Outcome Variable: Students’ Attitudes | Model | R | R2 | MSE | f-Value | df1 | df2 | p-Value |

| Constant | 0.0747 | 0.0056 | 0.7905 | 0.6617 | 1.0000 | 118.0000 | 0.4176 | |

| Model 3 | coeff | se | t-value | p-value | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Constant | 3.1275 | 0.5088 | 6.1472 | 0.0000 | 2.1200 | 4.1350 | ||

| University attributes | 0.1027 | 0.1262 | 0.8135 | 0.4176 | −0.1473 | 0.3526 | ||

| Effect/Relationship | coeff | se | t-Value | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of X on Y | 0.1027 | 0.1262 | 0.8135 | 0.4176 | −0.1473 | 0.3526 |

| Direct effect of X on Y | −0.0330 | 0.1727 | −0.1911 | 0.8487 | −0.3750 | 0.3090 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y => SRC | coeff | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| 0.1357 | 0.1290 | −0.1186 | 0.4073 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elareshi, M.; Ben Romdhane, S.; Ahmed, W. Evaluating University Attributes and Their Influence on Students’ Attitudes: The Mediating Role of Social Responsibility Communication. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080183

Elareshi M, Ben Romdhane S, Ahmed W. Evaluating University Attributes and Their Influence on Students’ Attitudes: The Mediating Role of Social Responsibility Communication. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080183

Chicago/Turabian StyleElareshi, Mokhtar, Samar Ben Romdhane, and Wasim Ahmed. 2024. "Evaluating University Attributes and Their Influence on Students’ Attitudes: The Mediating Role of Social Responsibility Communication" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080183