Abstract

Social sustainability that starts from the workplace is a relevant factor for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Based on this need, this study analyzes the role of virtuous leadership as facilitator of health and inclusive work environments that integrate followers’ psychological well-being and their attitudes towards people with disabilities. An exploratory design was used with latent variables to assess the proposed virtue-based ethical leadership adjustment model for social sustainability, which presented efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious adjustments for its operationalization. In conclusion, virtuous leadership plays a relevant role in the development of followers’ psychological well-being, and attitudes towards people with disabilities in the workplace, contributing to the social sustainability criteria from the work environment.

1. Introduction

According to the Brundtland Report, sustainability is defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (UN, 1987, p. 55). Although sustainable development implies a balance between the environmental, economic, and social pillars of sustainability, research has mainly focused on the environmental and economic dimensions (Murphy, 2012; López et al., 2017). In connection, social indicators are not as easily identifiable and quantifiable as environmental and economic indicators of sustainability (Fatourehchi & Zarghami, 2020). However, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) emphasize justice, social equity, and capacity to share well-being intergenerationally as essential pillars of sustainable development (Holden et al., 2014).

Sustainable development will be unattainable without the improvement of the quality of life of people, guaranteeing justice, peace, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, i.e., through social development (UN, 1995). In this sense, this work is based on research relating the role of virtuous leadership in mental health (Das & Pattanayak, 2023; Di Fabio & Peiró, 2024; Inceoglu et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2020; Wang & Hackett, 2016; Jensen & Luthans, 2006; Stajkovic & Stajkovic, 2025; Ronda-Zuloaga, 2024; Vásquez & Espinoza, 2024) and the attitudes towards the inclusion of people with disabilities in the workplace (Shore & Chung, 2023; Papakonstantinou & Papadopoulos, 2019; D’Souza & Kuntz, 2023; Ferdman, 2022). We worked with three models: virtue-based ethical leadership (Riggio et al., 2010; Livacic-Rojas & Rodríguez-Araneda, 2024), psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989; Véliz, 2012), and reactions towards people with disabilities (Popovich et al., 2003; Copeland et al., 2010) as criteria for social sustainability.

Basic needs like employment are non-negotiable, and people have a right to aspire to more than their mere satisfaction. Sustainable development offers everyone the opportunity to realize the desire for a better life (UN, 1987; Holden et al., 2014), which comprises multiple health dimensions, including mental health (SDG 3) and overall well-being, as well as full participation in the work landscape.

The promotion of inclusive and sustainable growth, employment, and decent work for everyone (SDG 8), together with the reduction in inequalities to make progress in long-term social and economic development, curb poverty, and protect the sense of fulfillment and self-esteem (SDG 10 and 1), are key elements for the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development (UN, 2015). Likewise, fostering peaceful and inclusive societies, creating efficient institutions (SDG 16), and promoting mental health and well-being (SDG 3) are fundamental pillars that contribute to psychological and social well-being both in and out of the workplace.

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO, 2024b), decent work allows people to realize their aspirations during their work life, giving them access to productive employment with a fair income, as well as safety, social protection, personal development, social inclusion, freedom, and conditions of equal opportunities and treatment. These conditions contribute, among other things, to the reduction in poverty, especially in socially marginalized groups, such as people with disabilities (Kenny & Di Fabio, 2024), who are more exposed to precarious work. The latter is characterized by uncertain conditions and continuity, restriction of rights, limited protection, and lack of freedom (Allan et al., 2021).

Social sustainability refers to the capacity of a society to remain balanced and cohesive for a long time, guaranteeing the inclusion and well-being of all its members, regardless of their origins or identities (Shore & Chung, 2023). Polese and Stren (2000) define social sustainability as the development that fosters social integration and improvements in quality of life for all the segments of the population. According to the systematization conducted by Fatourehchi and Zarghami (2020), some of the most relevant criteria for social sustainability are justice, integration, social well-being inclusion, equity, social and human capital, health and psychological and physical well-being, satisfaction, and work well-being, among others.

In the social and labor dimensions, sustainability psychology points to the establishment of organizational responsibility to improve the growth of people, strengthening their health and well-being (Di Fabio & Peiró, 2024). Sustainability cannot be conceived without considering the active role of the involved parts, especially of leaders. When leaders practice inclusion principles during their interaction with teams, they create a work environment where everyone can contribute, regardless of their cultural identity, strengthening relationships, improving well-being, and valuing diverse skills and perspectives (Shore & Chung, 2023).

This strengthens relationships, improves well-being, and allows for acknowledging and taking advantage of diverse skills and perspectives (Shore & Chung, 2023). In this way, managed inclusion reinforces social sustainability by guaranteeing that different perspectives are valued, promoting cohesion within the group and ensuring that people are addressed from fair and equal management. By doing so, organizations prepare for facing challenges in the long-term, promoting not only their success but also the well-being of the entire work community.

Social sustainability in the organizations is based on ethical principles and inclusive practices that promote collective well-being. Batstone (2003) identifies key principles to build sustainable and morally defendable organizations, among which are responsibility, transparency, community, honesty, decency, sustainability, diversity, and humanity. These principles underscore the importance of treating workers with decency, which includes their participation in decision-making, equal relationship management, diversity, and respect for human rights in all aspects. Leaders play a central role in the implementation of these principles, since their behavior and positive influence can generate healthy and inclusive work climates (Johnson, 2021). Through moral leadership (Cardona & Wilkinson, 2009; Cardona & García-Lombardía, 2011), leaders affect the mental, social, and physical health of workers (Koenig et al., 2024) and create the conditions for people to thrive (Newstead et al., 2020).

According to Koenig et al. (2024), some mental health and well-being determinants are genetics, prenatal factors, childhood, adolescent and adulthood environments, interaction between genes and environment, adaptative cognitions (positive cognitions or absence of cognitive distortions), social support networks, healthy behaviors (physical exercise, healthy eating habits, absence of overweightness and obesity, adequate sleep hygiene, absence of tobacco, alcohol and other substances consumption, resilience), and personal decisions (about family, friends, coworkers; confrontation of negative events; health, and time and financial management).

Some personal decisions (overlapping with psychological and behavioral factors) that influence mental health are habits and personality traits, which are the consequence of actions repeated over time. When these are positive and healthy, they are denominated virtues. In Christian Western societies (48% of Chile’s inhabitants are Catholic; Centro de Estudios Públicos, 2024), virtues are the foundation for moral virtues as they promote healthy and positive interpersonal relationships with others.

These same authors (Koenig et al., 2024) believe that some of the cardinal virtues that benefit mental health and well-being are prudence (practical intelligence), justice (giving other what they deserve), temperance (moderation and self-control), and fortitude (persistence in adversity); these are related to theological virtues (faith, hope, and charity). In turn, cardinal virtues are positively related to humility, responsibility, patience, honesty, veracity, honor (respect for others), loyalty, friendship, sociability, kindness (to care about the well-being of others), gratitude, equanimity, forgiveness capacity, and altruism, among others.

In line with the above, Ronda-Zuloaga (2024) indicates that cardinal virtues are fundamental in organizations because virtuous leadership (being based on ethics and sustainability) generates trust and good outcomes. Virtues in this context can manifest in the pursuit of happiness, respect for feelings, life, and freedom (prudence); acting right and without being afraid of the consequences (fortitude); relating to others with humility, discipline, education, austerity, without excessive banality and eccentricity (temperance); and acting coherently and consistently, seeking one’s own and others’ well-being (justice). In this context, the author indicates that justice is the virtue that comprises other virtues, as well as the base for interpersonal relationships.

This study was conducted with Chilean population. According to the official numbers of the National Council for the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Consejo Nacional para la Implementación de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible, 2023), systematic work in favor of social sustainability can be observed in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals. Particularly in mental health, data on SDG 3 show a suicide mortality rate of 8.2, which is declining but is still 4:1 higher in the men/women ratio, resembling the global panorama yet with a higher magnitude. To meet this goal, the Chilean government has launched public policies and programs for strengthening leadership and governance, promoting mental health, preventing suicide, as well as laws for inclusion. Regarding the reduction in inequality proposed by SDG 10, Chile exhibits a Gini Index of 43.0, whose decline reflects progress in this matter (World Bank, 2025). In addition, according to the 2017 data, the percentage of individuals who reported having felt personally discriminated against is 11.2% (Consejo Nacional para la Implementación de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible, 2023). Nevertheless, in terms of progress in the citizens’ quality of life, the Better Life Index (OECD, 2025) yielded an average of 6.2 for overall life satisfaction measured in a 0-to-10 scale, which is below the OCDE average, 6.7. In turn, 17.6% of the adult population in Chile has a disability, and this bracket of the population exhibits a low employment rate (43.9%). In addition, work-related mental health indicators show that a concerning 67% of occupational diseases are due to mental health disorders (Superintendencia de Seguridad Social, 2023). As observed, social sustainability is complex in terms of both mental health and the inclusion of people with disabilities, which encourages us to delve into ways of improving this scenario, specifically at the workplace and through those who assume responsibilities, i.e., the leaders. However, no data on virtuous leadership is found at the national level.

- Objective:

The aim of this research is to assess whether virtue-based ethical leadership, followers’ intrinsic psychological well-being, and their affective reactions toward people with disabilities in the workplace allow us to propose the existence of a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability.

- Hypothesis

- Virtue-based ethical leadership in the workplace is significantly related to followers’ intrinsic psychological well-being.

- Virtue-based ethical leadership is significantly related to followers’ affective reactions toward people with disabilities in the workplace.

- Followers’ intrinsic psychological well-being is significantly related to their affective reactions toward people with disabilities in the workplace.

- Virtue-based ethical leadership, followers’ intrinsic psychological well-being, and their affective reactions toward people with disabilities in the workplace together contribute to at least 75% of the explained variance in the evaluation of a model for a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability.

- The first-order model of a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability in the workplace presents an efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious fit.

- The second-order model of a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability in the workplace presents an efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious fit.

From the conducted work, it is concluded that virtuous leadership plays a relevant role in followers’ psychological well-being and their positive attitudes toward people with disabilities in the workplace, being a promoter of social sustainability in work environments.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Virtuous Leadership for Social Sustainability in the Work Environment

Newstead and Riggio (2023) emphasize that virtues are essential for effective leadership. Virtuous leaders are characterized by their ability to recognize and act correctly, at the right time, and for the right reasons (Kilburg, 2012). A virtuous leader ethically models followers’ behaviors, improves employees’ well-being (Wang & Hackett, 2016; Hendriks et al., 2020), their affective experience (Abdelmotaleb & Saha, 2019), their individual and organizational performance (Hendriks et al., 2020), and their happiness (Nassif et al., 2021). In addition, having virtuous leaders and perceiving them as such positively impacts the development of a more virtuous organizational climate, improves objective work characteristics, and cements a trust-based subjective process (Hendriks et al., 2020). The impact of virtuous leaders transcends the individual sphere by promoting a healthy and inclusive work environment aligned with the principles of safe and healthy work as a fundamental right (ILO, 2024a; Kenny & Di Fabio, 2024). This ethical approach in leadership strengthens not only the social cohesion and sustainability in organizations, but also the capacity of leaders to face challenges in the long term, guaranteeing that people can thrive in equal and resilient work environments, contributing to the achievement of the SDG in a broad sense.

Character and virtues play a fundamental role in several leadership styles, such as ethical, service, and transformational leadership. However, these models do not present a systematized set of virtues, nor do they focus on the leader’s character. Instead, they adopt a deontological perspective, based on the obligation to act, or a teleological perspective, centered on the consequences of actions (Hackett & Wang, 2012; Hendriks et al., 2020). The concept of virtuous leadership stems from virtue ethics and defines virtuous leaders as those whose character and voluntary, intrinsic, and intentional behavior are grounded in core virtues such as prudence, temperance, justice, courage, and humanity, which are consistently deployed in relevant contexts. As opposed to other value-loaded leadership models, virtuous leadership (Aristotelian, eudemonic philosophy) seeks the continuous moral development of both the leader and followers, as well as the achievement of their maximum potential (development of the human capital of the whole organization, i.e., with an expansive view) through promoting a virtuous culture, pursuing the greatest good, contributing to well-being and trust (social capital), and focusing not only on the organizational outcomes. Furthermore, as virtues stem from characterological elements, they can be molded, formed, and consolidated by nurturing moral excellence habits through deliberate practice and social commitment so that they become common to different contexts, beyond specific work scenarios. In connection, virtuous leadership has a more long-term approach that is consistent with the vision of sustainability and its intergenerational approach.

A framework centered on this approach is the virtue-based ethical leadership model proposed by Riggio et al. (2010). This model underscores the importance of virtues as a basis for efficient leadership, identifying key behaviors such as prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice. Justice, understood as giving each person what she deserves, is fundamental to fostering positive interpersonal relationships in the workplace. It also supports the social sustainability principles, which require equality and inclusion, and contributes to the achievement of decent work (SDG 8) and the reduction in inequalities (SDG 10), the establishment of solid institutions (SDG 16), and an increase in the degrees of trust and respect. This virtue is complemented with humility (acceptance of one’s own and other limitations), affability (communicating the truth with openness and affection), and generosity (acting without expecting personal benefits). In this way, when a leader is fair, he focuses and ensures equal opportunities, decision-making equality, and the elimination of structural barriers (Ensari & Riggio, 2022). Certainly, social sustainability is reflected in this approach as justice is fundamental for fostering inclusive and equal work relationships (SDG 8, 10 and 16), promoting social integration in the workplace and positively impacting the well-being of employees (SDG 3) (Hendriks et al., 2020; Wang & Hackett, 2016).

Fortitude is also essential as it allows leaders to keep calm and persevere in adverse or emotionally challenging situations (Riggio et al., 2010) and to stand firm in their values and ethical principles, even under external pressure (Cameron, 2012). It is key for the establishment of justice and solid institutions (SDG 16). In addition, temperance is the capacity to regulate emotions and impulsive reactions, maintaining stability in decision-making (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) so as to facilitate self-regulation, moderating the reactions to positive and negative contingencies (Riggio et al., 2010). The above is essential to protect mental health and emotional well-being at work, preventing the formation of stressful work environments (SDG 3) (Ciulla, 2014).

Lastly, Havard (2019) and Riggio et al. (2010) believe that prudence translates into a decision-making process that implies three key stages: assessment (seeking evidence from diverse sources), discrimination (pondering such evidence), and solving (making balanced decisions). Prudence, as the capacity to make the right choices considering collective well-being and ethical principles, contributes to decent work (SDG 8), e.g., by generating sustainable work strategies that balance economic growth and workers’ well-being (Bright et al., 2014) or fostering an ethical governance culture without corrupt or arbitrary practices (Ciulla, 2014).

As observed, the virtues in the model proposed by Riggio et al. (2010) not only strengthen decision-making but also interpersonal relationships, providing valuable tools to practice organizational leadership and contributing to the construction of healthier, more ethical and equal, and definitely more socially sustainable organizations.

2.2. Leadership and Positive Attitudes Towards People with Disabilities for Social Sustainability

Global crises of the 21st century, complexity, uncertainty, and accelerated changed affect people with disabilities disproportionately (Blustein, 2019), making inclusion and sustainable development difficult (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, 2023). According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2006), guaranteeing equal rights is essential, including the right to employment, under conditions of equality for people with disabilities. However, the negative perceptions about this population limit their work opportunities, which implies exclusion (Jasper & Waldhart, 2013; Shore & Chung, 2023).

Incorporating people from underrepresented groups in the workforce does not guarantee that their skills are taken advantage of, or that they themselves and their perspectives are included in their organizational decisions (Randel et al., 2018). This inclusion, understood as the recognition of an employee as a valued team member, the covering of their needs of belonging, and the acknowledgment of their individuality (Shore et al., 2011), is associated with social and emotional well-being (Dalessandro & Lovell, 2024), which are essential for the development of personal identity and life meaning in employees with disabilities (Flores et al., 2010), as well as a key criterion for social sustainability.

Inclusion experiences depend on efficient leadership (Randel et al., 2018) and the attitudes of coworkers. Inclusion initiatives, especially training, are influenced by attitudes, beliefs, and supportive behaviors from leaders and coworkers. Coworkers trust inclusion and related actions more when they perceive that leaders and other colleagues are committed to it (Dalessandro & Lovell, 2024).

Competitive employment and other forms of significant work activity are essential to the well-being of people with and without disabilities (Burke et al., 2013). Unemployed people experience higher rates of disorders such as depression, anxiety, elevated alcohol consumption, and lower self-esteem and quality of life levels. As indicated previously, in Chile, 17.6% of the adult population has a disability and its employment rate is 43.9%, compared to the 68.0% of adults without a disability, being higher in women and the 5th autonomous income quintile (Servicio Nacional de la Discapacidad, 2023). At the global level, in low-income countries, the occupation rate is 58.6% for men and 20.1% for women, while in high-income countries, this is 36.4% and 29.9%, respectively (WHO & World Bank, 2011). In addition, the lower educational and professional training level of this population contributes to their poverty and poor quality of life (Jasper & Waldhart, 2013). Therefore, work inclusion is essential to break the link between disability and poverty (WHO & World Bank, 2011).

Despite the legislative protection of the right to employment of people with disabilities, these people usually encounter barriers due to the prejudice of employers (Goodman et al., 2024). Research shows that, when specifically analyzing employment, participants are less likely to recommend the hiring or promotion of individuals with disabilities compared to employees without disabilities, despite the favorable attitudes towards the former in the workplace. These attitudes are one of the main barriers to the employment of people with disabilities and usually manifest as openly discriminatory practices (Copeland et al., 2010). Factors that influence the attitudes of leaders and management towards the hiring of people with disabilities include misconceptions (such as high costs, performance issues, support needs, team difficulties, etc.), distorted understanding of the legislation, lack of experience working along with people with disabilities (avoidant behaviors), as well organizational policies and cultures (D’Souza & Kuntz, 2023).

In turn, positive attitudes include the perception that individuals with disabilities generate more sympathy and social acceptance, which depends on the context, past experiences, and the quality of the interaction. These attitudes improve when the positive aspects and skills of people with disabilities are underscored, which facilitates their inclusion and quality of life (Nota et al., 2013).

A proposal that considers specific attitudes towards the work of people with disabilities (Popovich et al., 2003; Copeland et al., 2010) includes negative cognitive and affective reactions to working with them (such as beliefs that this will lead to increased workload, discomfort, and more supervision demands, among others), positive attitudes towards making accommodations for coworkers with disabilities (e.g., a positive disposition towards necessary adjustments), and positive attitudes towards the equal treatment of individuals with disabilities in the workplace (trust, appreciation, etc.).

Prioritizing the promotion of favorable attitudes of employers towards people with disabilities is fundamental to achieving effective work inclusion (Papakonstantinou & Papadopoulos, 2019). Through leadership, behavioral barriers among the other workers can be eradicated. Leaders and management are responsible for implementing reasonable adjustments such as including infrastructure, teams, and inclusive policies, but they are also responsible for the socialization of workers with disabilities, the modification of jobs, and the creation of flexible work agreements, among others (D’Souza & Kuntz, 2023).

Few studies have focused on how leaders create an inclusive work environment (Randel et al., 2018). It has been documented that, when leaders promote inclusion and act as role models, group members are likely to adopt such behaviors. This influence is stronger when inclusive behavior is constant over time and equal among members. In turn, a leader that practices exclusion can also foster excluding dynamics in the team (Shore & Chung, 2023). Therefore, positive and constructive beliefs in favor of diversity are essential. Randel et al. (2018) highlight that such beliefs arise from past experiences (including socialization, education, exposure to other cultures, or participation in tasks in which diverse perspectives are needed) and personality traits (such as openness to experience and tolerance of ambiguity). According to these authors, when leaders are inclusive, they foster justice and collaboration through the implementation of practices that promote active participation and a recognition of different perspectives. Through their approach, these leaders allow employees to maintain their identities and feel accepted by the group, which is crucial for organizational success in the long term. Inclusive leaders play a key role in the elimination of prejudices and systematic discrimination by creating an environment where employees feel safe, respected, and valued for their authenticity (Ferdman, 2022). This approach not only benefits diverse work groups but also ensures equal treatment for all the employees, promoting cohesion and strengthening collective identity within the organization (Ferdman, 2022). Thus, inclusive leadership significantly contributes to social sustainability, promoting an inclusion culture that benefits both individuals and organizations.

Based on the model proposed by the authors of this study, developing a culture of virtues—centered on justice, temperance, prudence, and fortitude—enables virtuous leadership to translate into the implementation of inclusion strategies promoted by leaders. These strategies would be aimed at challenging and modifying, for example, behavioral barriers against individuals with disabilities, positively influencing their quality of life (SDG 3), as well as their hiring, work retention, and promotion (SDG 1, 8, and 10). The implementation of these inclusion and no-discrimination policies, reasonable adjustments, work flexibility, organizational awareness, mentorship for inclusion, gap measurement and monitoring, among others, is also pertinent to this goal and should be part of the management by the organization leaders.

2.3. Leadership and Psychological Well-Being of Workers for Social Sustainability

Psychological well-being focuses on the development of human potential, the facing of existential challenges and the construction of a life purpose (Ryff, 2018; Keyes et al., 2002; Ryff et al., 2004). It is an indicator of mental and comprehensive health, as well as an essential part of personal and social growth (Ryff & Singer, 2006; Emadpoor et al., 2016). Ryff proposes the multidimensional model of psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Singer, 2008), which includes six fundamental dimensions: self-acceptance, understood as the capacity to maintain a positive attitude towards oneself despite the limitations; positive relationships with others, based on stable and significant stable bonds; autonomy, reflected in self-determination and personal independency; domain of the environment, which allows for molding or choosing favorable contexts to satisfy needs and aspirations; life purpose, linked to setting goals and objectives that give sense to existence; and personal growth, centered on the continuous development of individual potential and capacities. These dimensions significantly contribute to the strengthening of positive emotional and psychological health (Ryff & Keyes, 1995).

Sustainable development requires work conditions that favor the psychological well-being of individuals. In this sense, this model proposes that virtuous leadership—through the construction of healthy work environments and a virtue-based organizational culture that promotes the values of justice, equality, respect, and support—would contribute to people’s health at work and after work (SDG 3) and to the development of solid institutions, peace, and justice (SDG 16). The above could be monitored through the measurement of stress and burnout levels, psychological occupational diseases, organizational climate, and work satisfaction indexes, for example, and improved through the firm and timely management of leaders (fortitude, justice, temperance, and prudence).

Leadership is an essential factor to foster the well-being of employees, their prosocial behavior, physical and mental health, and work satisfaction (Das & Pattanayak, 2023). Currently, different leadership theories highlight the importance of promoting an organizational climate and culture oriented to sustainability, inclusion, and well-being. Sustainable organizations are characterized by generating conditions that turn them into positive and healthy environments, anticipating solutions to potential problems, promoting well-being, and valuing resources at different levels (individual, group, intergroup, organizational, and interorganizational). This approach underscores the need to integrate new elements in leadership styles (Di Fabio & Peiró, 2024). Some of the leadership styles associated with employee well-being are transformational, charismatic, authentic, ethical, empowering, service-oriented (Inceoglu et al., 2018), and virtuous leadership. All these approaches have the ethical-moral component in common and are value-charged.

Virtuous leadership has been documented to positively influence work and employee well-being (Hendriks et al., 2020). The perceptions of subordinates about the virtuous leadership of a supervisor are positively related to their general happiness and life satisfaction (Wang & Hackett, 2016). Nevertheless, the role of virtuous leadership in individual leaders, defined by a coherent set of virtues, in the work well-being of subordinates has been barely explored (Hendriks et al., 2020).

Human capital sustainability leadership—a superior order construct that includes ethical, sustainable, conscious, and service leadership—converges in its value-loaded approach and contribution to sustainability (Di Fabio & Peiró, 2024). Human capital sustainability leaders are committed to relational civility, the promotion of thriving, and the development of healthy, resilient workers and healthy organizations.

Service leadership promotes employees’ well-being and social sustainability by prioritizing human development and service to others. This approach, founded on ethical and sustainable principles (Greenleaf, 1982), emphasizes the importance of empowering workers, promoting their autonomy, and cultivating equal and socially responsible workspaces (Ensari & Riggio, 2022). Service leaders not only support the personal and professional growth of their team, but also generate trusting relationships and safe and fair organizational climates, which are key for employees’ psychological well-being (Das & Pattanayak, 2023). According to Van Dierendonck (2011), this leadership style is characterized by features such as humility, authenticity, interpersonal acceptance, and responsible administration, operating in dimensions that include empowerment, taking responsibilities, and receptiveness towards others’ well-being. In this framework, organizations are seen as platforms to train individuals capable of contributing to a more promising and sustainable future (Van Dierendonck & Nuijte, 2011).

Authentic leadership, in turn, favors climates of closeness, which are more inclusive, supportive, committed, and focused on developing strengths and are associated with high levels of organization citizenship that improve self-esteem and the prosocial conducts of its followers. It operates through modeling, the generation of learning processes, and repetition of inclusive behaviors (Ensari & Riggio, 2022). Studies have shown its positive impact on employees’ work satisfaction and subjective well-being (Jensen & Luthans, 2006), as well as the strengthening of the collective psychological capital (Moriano et al., 2011), emphasizing its leading role in the creation of positive and sustainable work environments.

Another type of value-loaded leadership is ethical leadership, which is defined by normatively appropriate behaviors such as trust, honesty, equity, and care, fostering solid relationships based on respect and support. This leadership style protects subordinates from unfair treatment, satisfies their relational needs, and improves their overall well-being (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Das & Pattanayak, 2023).

In a complementary line, caring ethical leadership focuses on care as a central moral value for social harmony. This approach implies paying attention to others’ needs, responding to them, and cultivating solid interpersonal relationships, underscoring ethical commitment and collective well-being (Stajkovic & Stajkovic, 2025).

Basal leadership is another type of leadership that converges with the ethical–moral approach. Some of its pillars (leader’s traits) are (1) the ability to generate trust based on competence, HIH character (humility, integrity, and honesty) and respect for others. Humility (knowing their own limitations and strengths) is related to the control of emotions through reason (virtue of temperance); integrity is doing the right thing regardless of the circumstances (virtue of fortitude); and honesty is the coherence between words, behaviors, thoughts, and values. According to Ronda-Zuloaga (2024), Zak (2017) proposes that people who work in companies with high levels of trust present less stress, more energy to work and productivity, less worker absenteeism due to sickness, and an increase in worker satisfaction; (2) determination to achieve results through strategic planning, management, and leadership to align general and individual objectives in the organization. Key behaviors in leaders are self-control and self-management, motivation, and perseverance (Ronda-Zuloaga, 2024); (3) the generosity to ensure the future is based on the ethics of the common good, which consists of prioritizing organizational (or institutional) achievements over personal achievements. Operationally, this translates into the achieving of results and trust. This binomial can give birth to four types of leaders: (i) virtuous leader (high results and high trust); (ii) furtive leader (high results and low trust); (iii) diminished leader (low results and high trust); and (iv) incompetent (low results and low trust). Basal leadership favors sustainability in organizations by considering the profitability dimensions (results achievement), respect (trust), social work (well-being, commitment, generosity, and features of a good work environment), and a good corporate government (complying with standards based on self-control, prevention and virtuous leadership; Ronda-Zuloaga, 2024).

3. Materials and Methods

Participants: The participants of the study (work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions) were selected during the pandemic in Chile (in a context of restricted mobility due to the health lockdown and remote work requirements) through non-probabilistic sampling, by convenience (n = 759), and with a sample selection error of 0.0356. The sample size adequacy index is high (KMO = 0.93). In this context, Muñiz (2018), Muñiz and Fonseca-Pedrero (2019) and Aliaga (2021) indicate that in studies with metric analyses, the number of participants should be estimated from five to ten people per number of answered items. As indicated in the following subsection, the number of items administered was 65; therefore, 325 to 650 people should answer the survey.

In stage 1, participants were recruited through employment platforms (44.1% of the total sample). In stage 2, databases from different Chilean universities were employed (42.3%). In stage 3, recruiting was conducted through a call from public, private, and social institutions (13.6%). A private invitation was sent to participants who met the inclusion criteria. In sociodemographic terms, the sample distribution by variable was sex (men 23.3%; women 22.1%; non-declared voluntarily 54.5%), years of work experience (0–2 years 16.2%; 2–5 years 9.6%; 5–10 years 13.7%; more than 10 years 60.5%), and type of organization (public 25%; private 63.8%; social 5.0%; other 6.2%).

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. The personal handling of the data was ethically guaranteed, and written informed consent was obtained, which was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee “Scientific Ethics Committee of the Office of the Vice-President for Research, Innovation and Creation of the University (Anonymized version)”, ethics report number 071/2020, (Anonymized version), 26 March 2020. Finally, no dropouts or data losses were recorded during the study, and, therefore, no data imputation procedure was conducted to avoid adverse effects on the estimation of statistical indices (Livacic-Rojas et al., 2020).

Instruments: The study used the version of the Leadership Virtues Questionnaire (LVQ. Riggio et al., 2010). The questionnaire contains 19 Likert-type items [ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)] that measure the virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. The metric properties of the instrument adapted and standardized in Chile by the authors (Livacic-Rojas & Rodríguez-Araneda, 2024) were obtained in 759 cases (sampling error = 0.0356; KMO = 0.91, acceptable sample size) with a reliability of 0.98 (with Tucker–Lewis index), a validity analysis by (i) percentage of explained variance (96.27); (ii) second-order confirmatory factor analysis with χ2 (117) = 676.76 (inefficient absolute fit); CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90 (efficient comparative fit); SRMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.08 (efficient parsimonious fit); (iii) estimated cross-validity index of 0.99 (ECVI = 0.99), and (vi) parallel analysis (MAP4) with an explained variance of 74.09 (p < 0.0001) for four dimensions through analysis with 10,000 replicated simulations.

The subscale Affective Reactions to People with Disabilities in the Workplace from the Disability Questionnaire (DQ, Popovich et al., 2003; Copeland et al., 2010) includes 17 items grouped into three factors: negative cognitive and affective reactions (reliability = 0.83), positive attitudes toward accommodating coworkers with disabilities (reliability = 0.82), and positive attitudes toward equal treatment of people with disabilities in the workplace (reliability = 0.92). The items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 7. For this study, the instrument was adapted and standardized to Chile by the authors. In a sample of 759 participants (sampling error = 0.0356; KMO = 0.97), the global reliability was 0.98 (Tucker–Lewis Index), and validity through explained variance was 98.10%. A first-order confirmatory factor analysis yielded the following results: χ2 (113) = 586.89 (p < 0.05, inefficient absolute fit), CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95 (efficient comparative fit), SRMR = 0.04, and RMSEA = 0.07 (efficient parsimonious fit). Furthermore, the estimated cross-validity index was 0.88 (ECVI = 0.99), and parallel analysis (MAP4) showed an explained variance of 72.65% (p < 0.0001) for the three dimensions based on an analysis with 10,000 replicated simulations.

In turn, the Multifactorial Questionnaire of Psychological Well-being (Ryff, 1989) is an instrument that was standardized in Chile by Véliz (2012), which reported internal consistency indices (Cronbach’s α) by the dimensions of self-acceptance 0.79; positive relationships 0.75; autonomy 0.67; mastery of the environment 0.62; purpose in life 0.54; personal growth 0.78. Regarding validity, the following adjustment indices were reported: RMSEA (0.068), CFI (0.95), NNFI (0.94), and SRMR (0.060). For this research, the instrument was adapted and standardized for Chile by the authors. In a sample of 759 participants (sampling error = 0.0356; KMO = 0.97), the following provisional psychometric properties were obtained: global reliability was 0.95 (Tucker–Lewis Index), and validity through explained variance was 75%. A first-order confirmatory factor analysis yielded the following results: χ2 (247) = 506.57 (p = 0.0001, inefficient absolute fit), CFI = 0.87, TLI = 0.85 (inefficient comparative fit), SRMR = 0.06, and RMSEA = 0.06 (efficient parsimonious fit). Furthermore, the estimated cross-validity index was 2.16 (ECVI > 1.0), and parallel analysis (MAP4) indicated an explained variance of 87.69% (p < 0.0001) for the six dimensions based on an analysis of 10,000 replicated simulations. A second-order factor analysis (parallel analysis) was conducted, which converged into four statistically significant dimensions. From these, a new subfactor emerged, with an explained variance of 97%, derived from the dimensions of self-acceptance, purpose in life, and personal growth. This subfactor, named Intrinsic Psychological Well-being, was the subfactor used in this study.

Procedure: An explanatory design with latent variables was employed (Ato & Vallejo, 2015). Once participants were recruited, data collection was conducted according to the International Test Commission (ITC) guidelines and the Norma UNE-ISO 10667 (2013) (UNE-ISO 10667 standard, 2013, in force during the conduction of the study). The questionnaires were applied online between 1 May 2021, and 27 September 2022, through a private link sent to each participant. After data collection, statistical analyses were conducted to assess the metric properties and the hypotheses of the level one designs (correlation coefficients). At level two, an Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering analysis was conducted with PROC CLUSTER and average distance between all pairs of data (SAS Institute, 2019) to define the groups objectively (based on data and regardless of variables) in association with a percentage of explained variance between 70% and 80% (O’Rourke et al., 2005; O’Rourke & Hatcher, 2013; Reyes & Reyes, 2024). Lastly, at level three, a first- and second-order confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the efficiency of the statistical model (Pérez, 2001, 2016).

Data analysis: The data were analyzed using the statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2019). For the analysis of the metric properties, the dimensions of test reliability (statistical techniques Cronbach’s alpha and Tucker–Lewis), validity (statistical techniques, quadratic canonical correlation coefficients, and factor analysis for consistency between theoretical and empirical factor structures; graphical techniques: sediment plots), and the mean square error for the diagonal of the residual matrix were evaluated. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and cluster analysis (grouping of dimensions not originally detected) were used to contrast the hypotheses. For the level three analysis, the fit of the first and second order model was evaluated through five substages: specification, identification, estimation, evaluation, and re-specification of the model. In this analytical context, four evaluation criteria associated with the respective theoretical ranges for the inferential decision and subsequent discussion were followed for the model fit [see criteria proposed by Pérez (2016), O’Rourke and Hatcher (2013) and Abad et al. (2011)]: (a) analysis of the absolute statistical fit χ2/υ (degrees of freedom) p > 0.05); (b) analysis of the comparative statistical fit: AGFI [with theoretical ranges as follows; AGFI ≥ 0.95 or more (optimal); 0.90 ≤ AGFI ≤ 0.94 (acceptable); AGFI < 0.90 (poor)]; CFI [(comparative fit index where CFI > 0.95 or more (optimal); 0.90 < CFI < 0.94 (acceptable); CFI < 0.90 (poor)]; TLI [Tucker–Lewis index, where TLI > 0.95 or more (optimal); 0.90 < TLI < 0.94, (acceptable); TLI < 0.90 (poor)]; (c) parsimonious statistical fit analysis: SRMR [normalized root mean square residual with theoretical range of 0.05 < SRMR < 0.079 (acceptable); 0.08 < SRMR < 0.099 (marginally acceptable); SRMR > 0.10 (poor)]; RMSEA [root mean square error of approximation with RMSEA. Theoretical range 0.06–0.08, where RMSEA < 0.06 (optimal); 0.061 < RMSEA < 0.080; RMSEA > 0.081 (poor)]; and (d) estimation of the cross-validity index: ECVI [expected cross-validation index (0.01 ≤ CVI ≤ 0.99] and graphical techniques: Path diagram.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Inferential Analysis: Stage One

Based on the results shown in Table 1, it is observed that the correlations between the 10 dimensions of the tests are statistically significant for 67% of the relationships analyzed (30 out of 45). However, according to the theoretical ranges reported by Tokunaga (2019), the impact is high in 16% (7 out of 45), moderate in 44.44% (20 out of 45), and low in 6.67% (3 out of 45). In addition, the dimensions of prudence, strength, negative emotional reactions, positive attitudes, and self-acceptance are those that present a significantly higher relationship with the dimensions of the other variables.

Table 1.

Statistical indices of correlations between the dimensions of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

4.2. Statistical Inferential Analysis: Stage Two

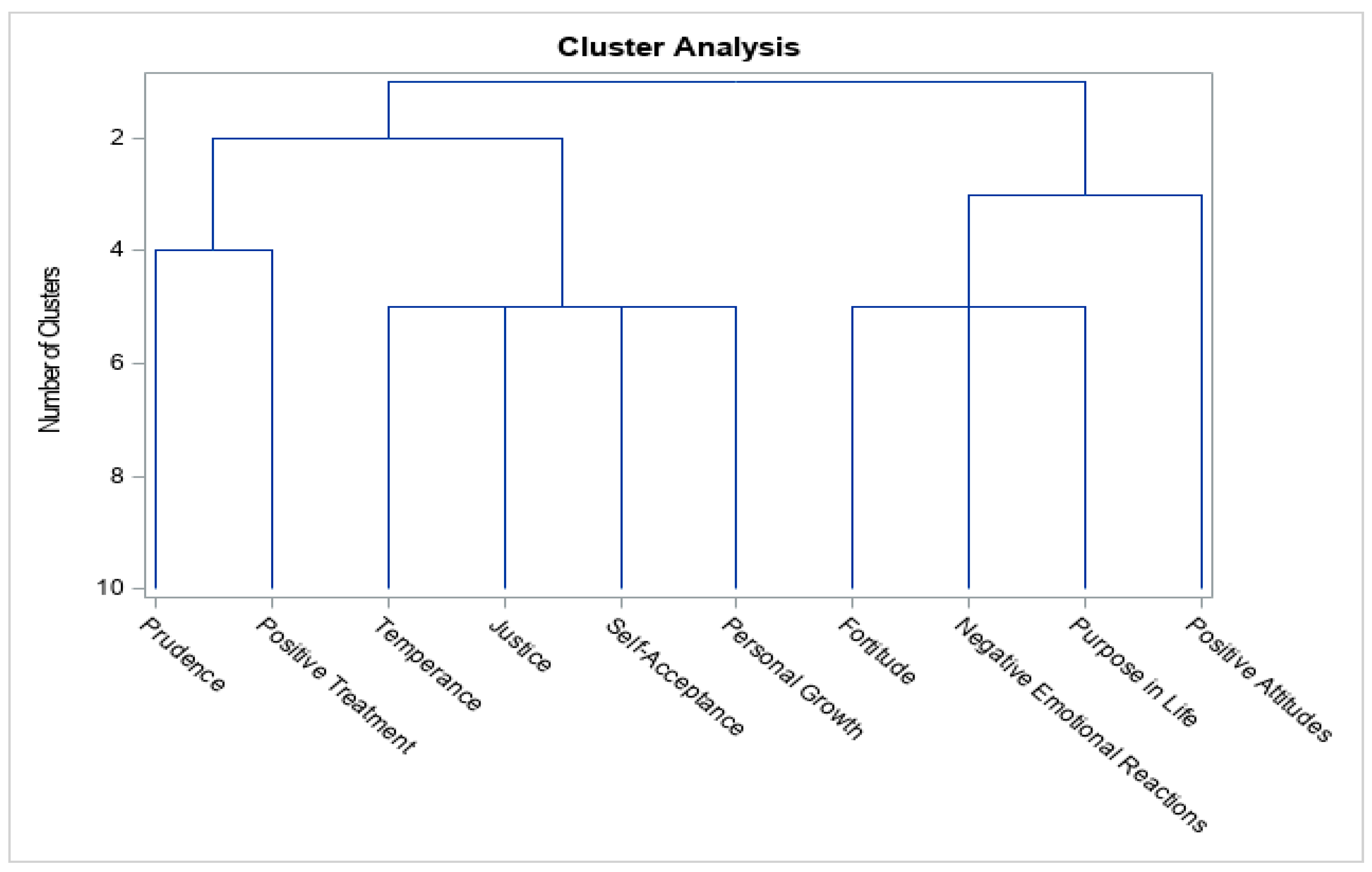

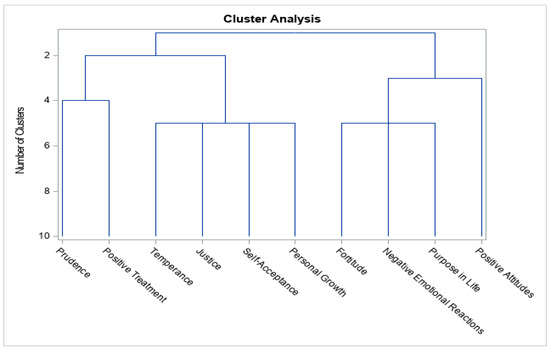

To identify patterns that reveal previously not considered hierarchical relationships among the different test dimensions, a cluster analysis was conducted to confirm that the model contained accurate variables for achieving a reasonable fit quality. In this sense, Table 2 shows the PROC CLUSTER syntaxis process. The clusters are the following: fortitude, negative reactions, life purpose (Cluster 1); temperance, justice, self-acceptance and personal growth (Cluster 2); positive treatment (Cluster 3); positive attitude (Cluster 4); and prudence (Cluster 5). In this analytical context, it should be noted that the last three clusters are formed by a single dimension, showing high independence and low error variance in the relationship hierarchical model. In other words, the model allows for operationalization, which in virtuous leadership (Ronda-Zuloaga, 2024) is expressed as a behavioral structure within organizations that is based on trust (conjunction of Clusters 5, 4, and 3) to obtain results (Clusters 2 and 1) as prudence (decision-making), positive attitudes (favorable disposition towards others), and positive treatment (display of positive attitudes), highly influence self-control behavior (temperance), equal treatment (justice), comprehensive development of individuals (self-acceptance and personal growth), negative emotional reactions (unfavorable attitudes) and life goals (life purpose).

Table 2.

Cluster analysis considering the dimensions of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

In connection, Figure 1 shows that the hierarchical organization of the variables re-grouped into five clusters to operationalize the behavior of virtuous leadership in organizations reaches a reasonable explained variance level (76%), following the recommendations in the empirical literature for the operationalization of variables or variable groups before assessing a model (O’Rourke et al., 2005; O’Rourke & Hatcher, 2013).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram for detection of originally not considered hierarchical relationships based on average distance between all data and the three tests applied and their dimensions.

In turn, in terms of visual inspection, Figure 1 shows that the hierarchical organization of the variables regrouped into five clusters is the one that reaches an explained variance of 75%, which the empirical literature recommends for operationalizing variables or groups of variables in models (O’Rourke & Hatcher, 2013).

In this context, Table 3 shows the inter-cluster correlation coefficients, which, if close to zero, would indicate that only the relationship between Cluster 1 and 2 would be the highest, consistent but functionally inverse. In turn, the relationship between Cluster 1 and 4 is the next configuration that provides the least information. The remaining relationships are located between low and moderate ranges (there would be independence between them).

Table 3.

Analysis of correlation between the cluster of the dimensions of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

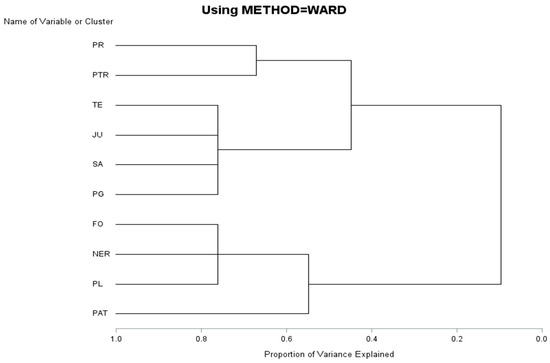

A fortiori, Table 4 shows the use of the five clusters indicated above and explains the greatest amount of variance in the attempt to operationalize a type of virtuous leadership that favors social sustainability through the use of statistical indices that regroup the dimensions of the tests of ethical leadership based on virtues, affective reactions towards people with disabilities, and intrinsic psychological well-being.

Table 4.

Total variance, proportion, and minimum proportion explained by clusters detected from hierarchical configurations not originally considered with the three tests applied, along with their dimensions and the elements that compose them.

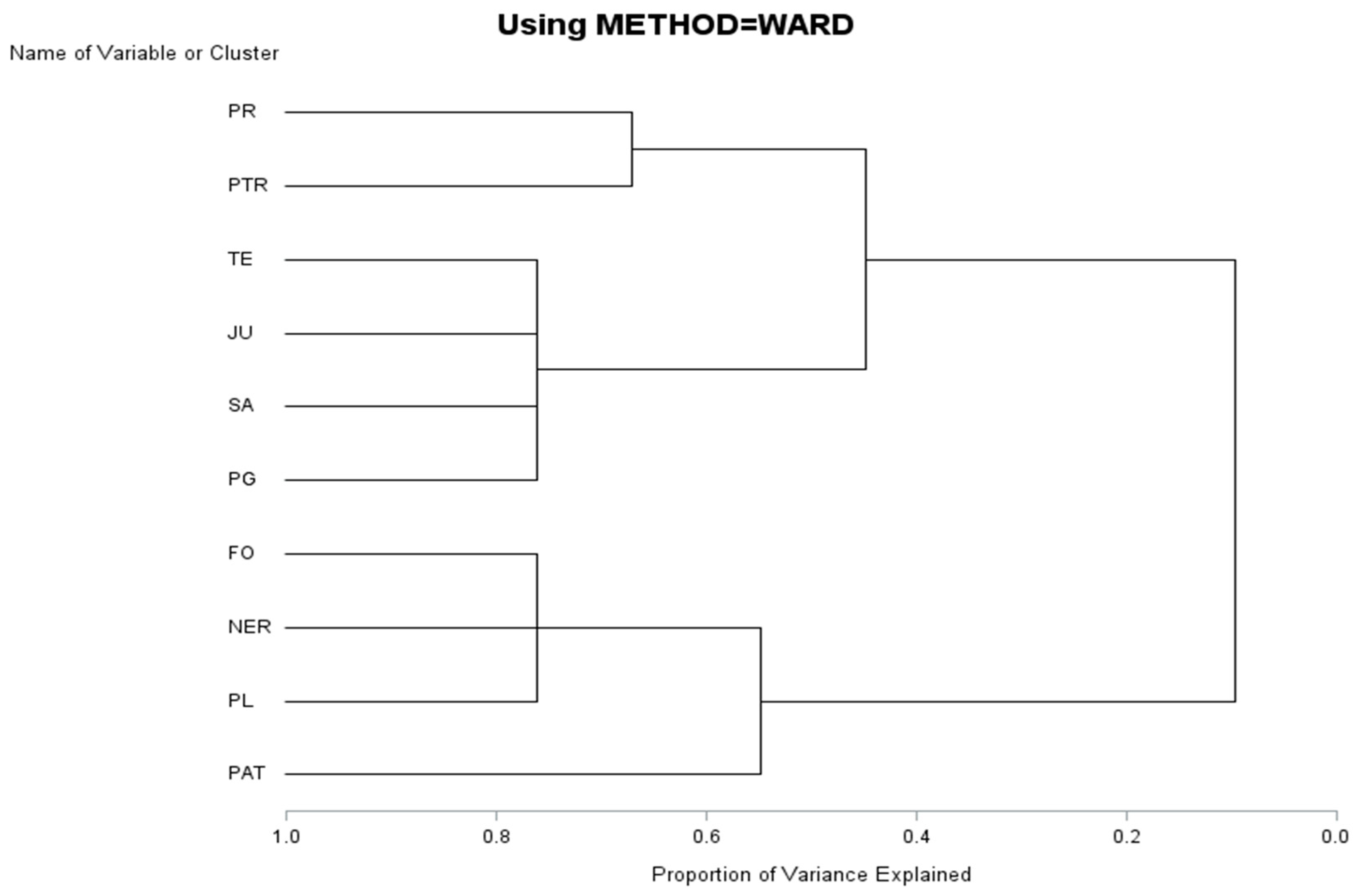

Figure 2 shows that the five clusters detected explain nearly 80% of the common variance, which makes it possible to evaluate the operationalization of a type of virtuous leadership for social sustainability based on the hierarchical organization of the dimensions of ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities, and intrinsic psychological well-being.

Figure 2.

Dendrogram for detecting hierarchical configurations not originally considered through the explained variance extracted from the three tests applied, their dimensions, and the elements that compose them. Legend: PR (prudence); PTR (treat); TE (temperance); JU (justice); SA (self-acceptance); PG (personal growth); FO (fortitude); NER (negative reactions); PL (purpose in life); PAT (positives attitudes).

4.3. Statistical Inferential Analysis: Stage Three

Analysis of the first-level fit of the three-factor model through consistency analysis between the theoretical and empirical factor structure.

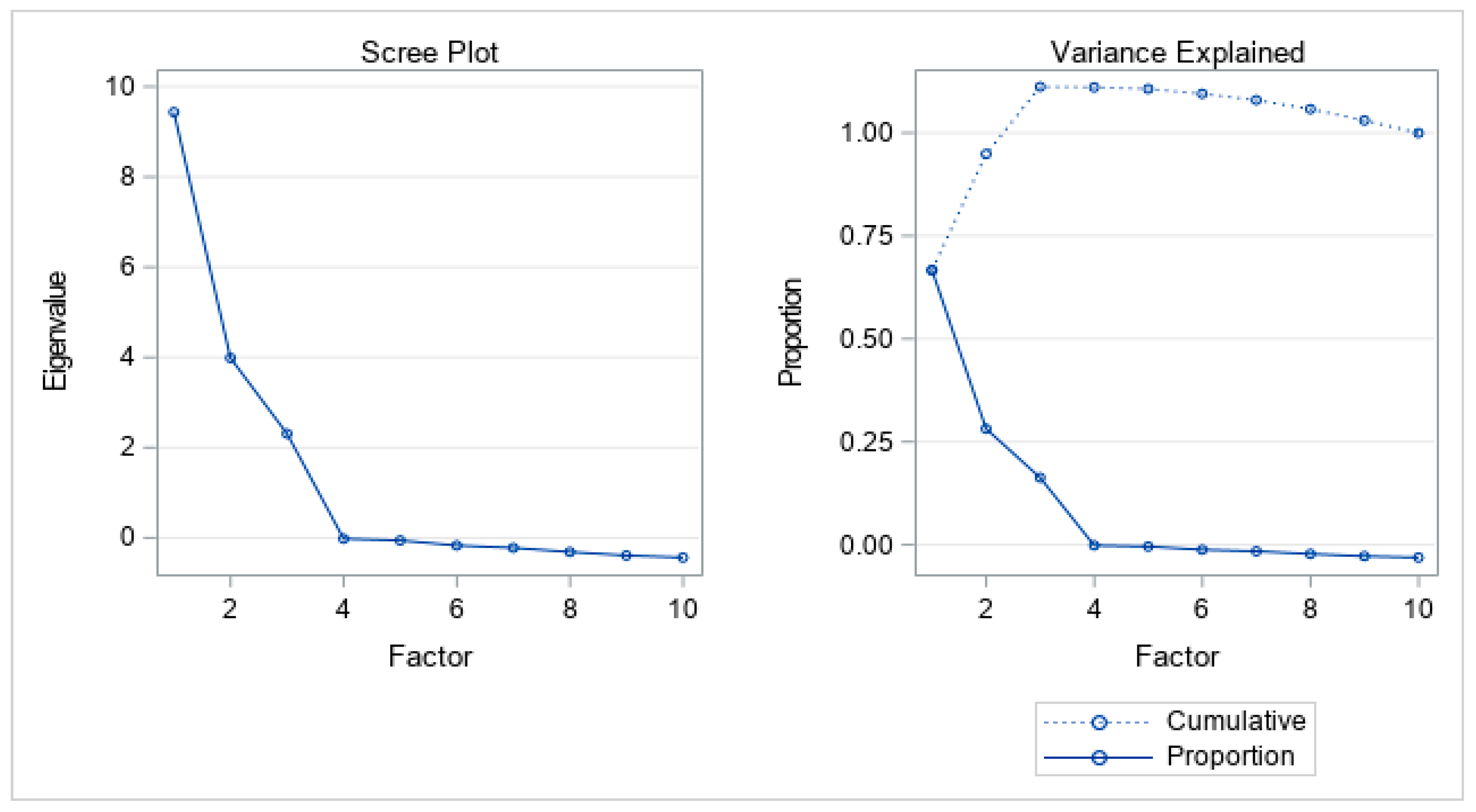

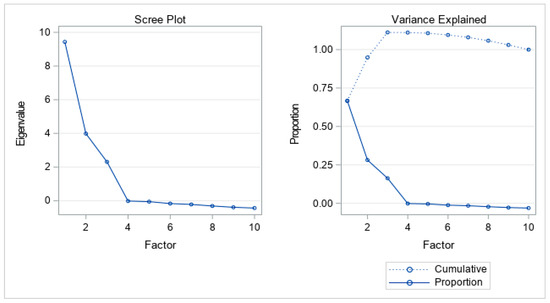

Based on the results observed for a three-dimensional hypothesis test, it is possible to conclude that there would be an adequate sample size (KMO = 0.7392) and consistency between the theoretical and empirical four factor structure [χ2 (18) = 7.9040, p = 0.98]. In this context, according to the criteria stated by O’Rourke and Hatcher (2013), the global reliability with the Tucker–Lewis method is 1.00, and the validity of the factors (through quadratic canonical correlations) would be 0.94 (LVQ), 0.87 (DQ), and 0.79 (IPWB). In turn, Figure 3 shows that the final estimates of the variance would be 72.19%.

Figure 3.

Scree plot of the dimensions of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

4.4. Analysis of Model Fit with Three Factors Using First-Order Factor Analysis

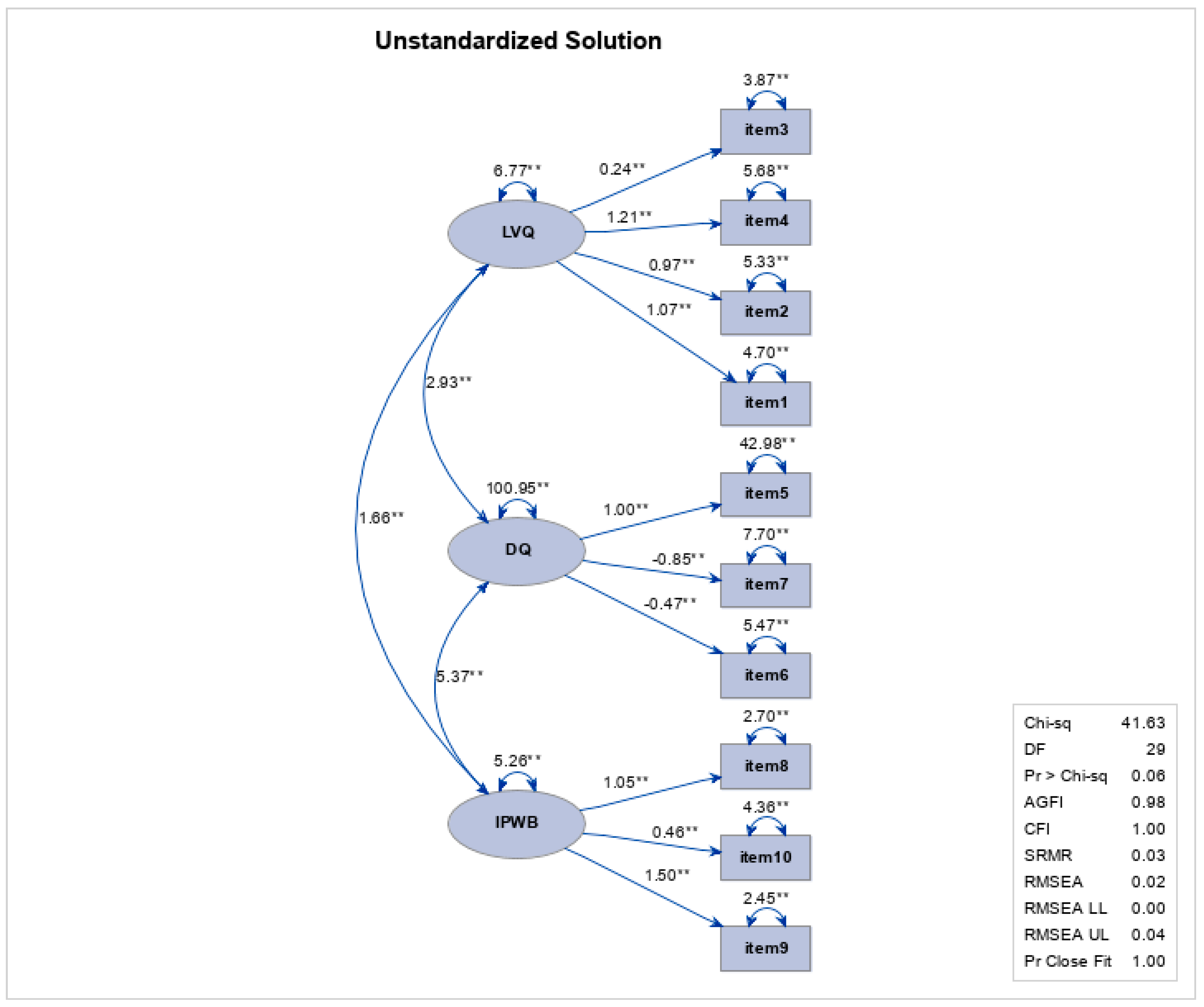

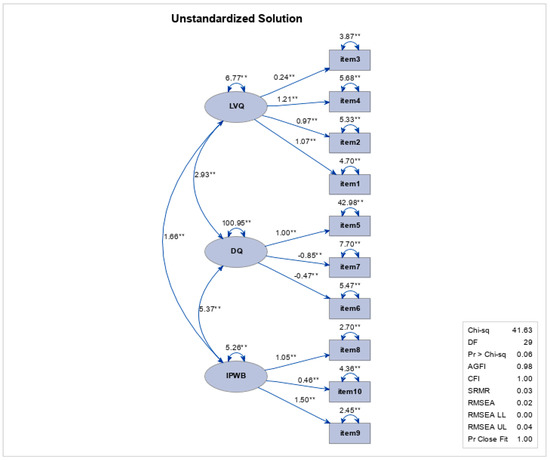

Based on the criteria proposed by Pérez (2016), O’Rourke and Hatcher (2013), and Abad et al. (2011), Table 5 shows the initial operationalization of the virtuous leadership model that contributes to social sustainability based on the three factors (and the elements that compose them) assessed through the maximum likelihood estimator and exhibits efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious efficiency according to the theoretical parameters. In turn, given that the estimation of the cross-validity index (CVI) is very close to zero (associated with the AIC parsimonious model), we could consider its high competitiveness compared to other models that attempt to operationalize it.

Table 5.

Statistical indices for first-order confirmatory factor analysis to assess the fit of the model of the virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in exercise leadership positions.

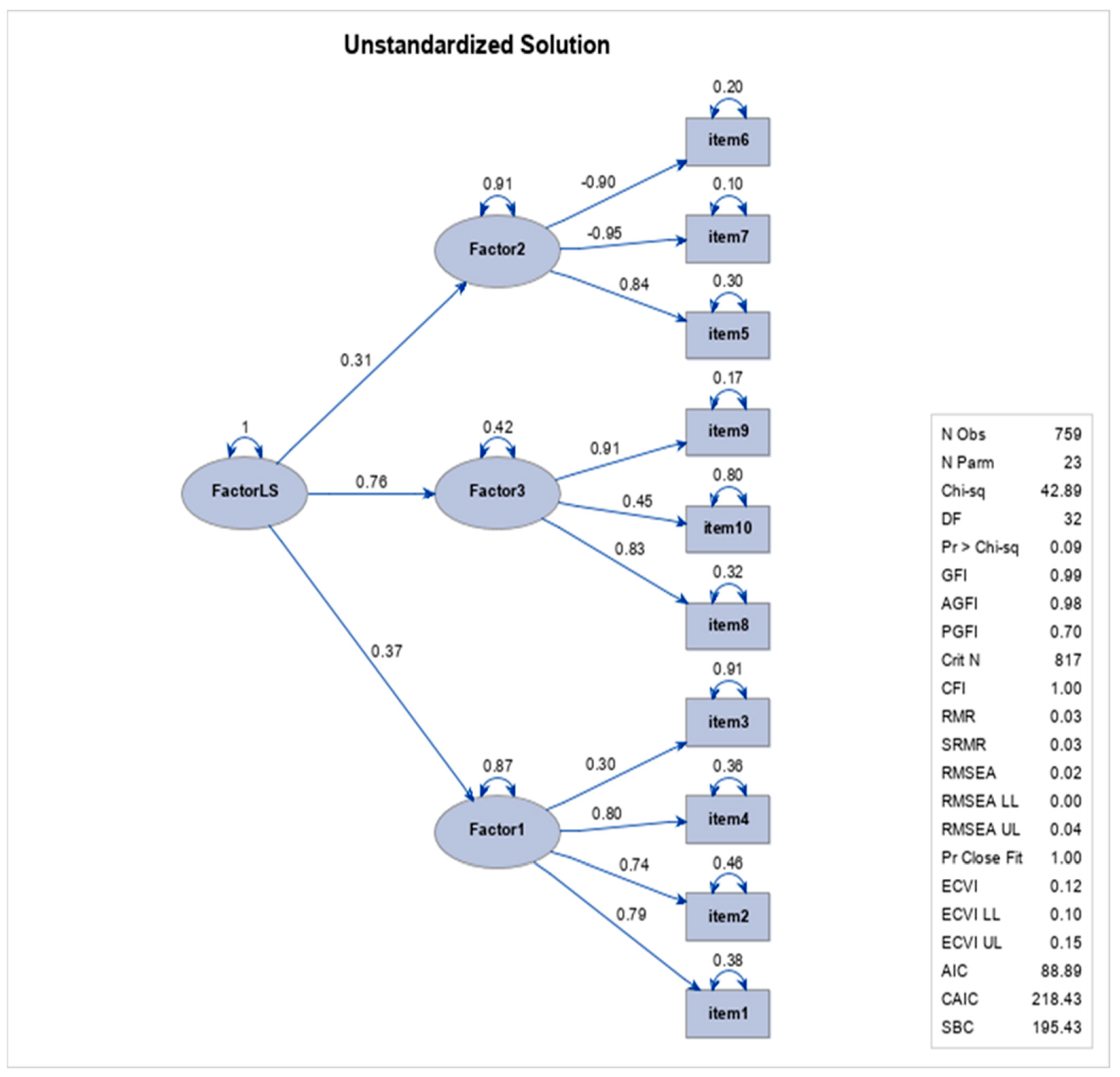

In parallel, Figure 4 shows the initial operationalization of the virtuous leadership model that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability. In this case, the three factors and the elements that compose the model are oriented in the same direction (configuration through positive covariance between them), which is statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Path diagram for the first-order factorial analysis of the model of the virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership functions. Legend: LVQ (Factor 1); DQ (Factor 2); IPWB (Factor 3); ** Statistically significant at the 0.01 level (p < 0.01).

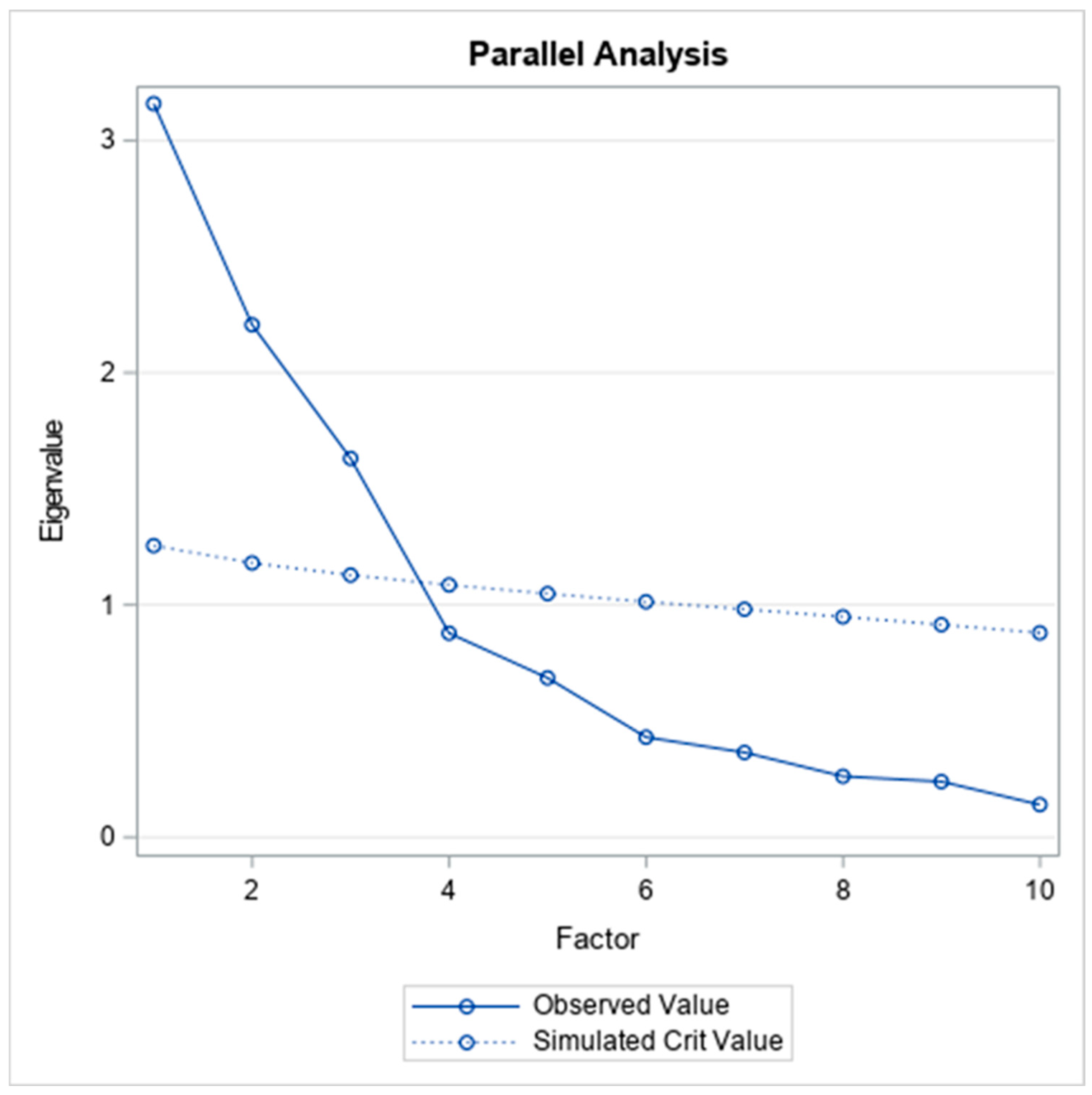

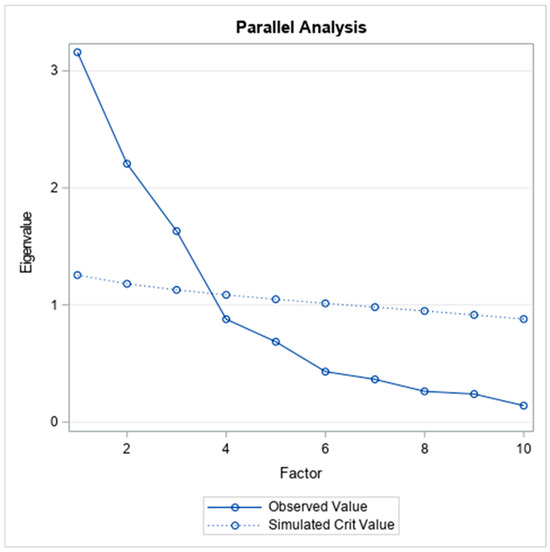

In light of the analyses above, if the initial operationalized model were to be extrapolated to other statistical populations, parallel analysis (Figure 5) could be used to find a very significant fit based on the results obtained from 10,000 simulations (using MAP4) for the three factors and their elements, which would explain 74.09% of the variance (p = 0.000). This is highly consistent with the data in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Figure 5.

Factor retention graph for parallel analysis with the MAP4 minimum partial correlation method for scores of ethical leadership based on virtues, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

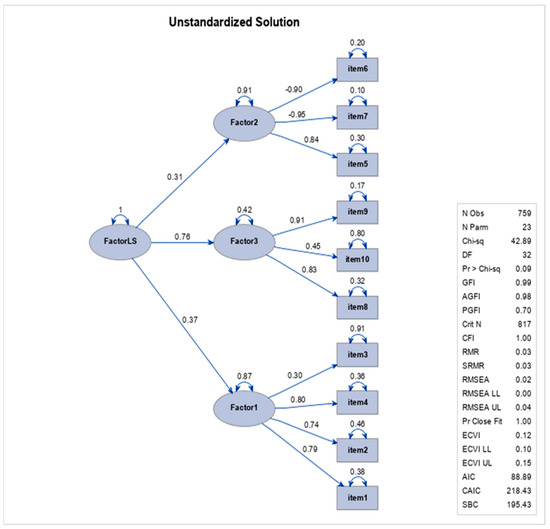

4.5. Analysis of Model Fit with Four Factors Using Second-Order Factor Analysis

Table 6 presents the second operationalization of the virtuous leadership model for sustainable management based on three factors (and the elements that compose them). Evaluated via maximum likelihood estimation, the model shows efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious efficiency adjustment indices. In turn, as the estimation of the cross-validity index (CVI) is very close to zero (which is associated with the parsimonious model with AIC), its high competitiveness compared to other models is reinforced.

Table 6.

Statistical indices for second-order confirmatory factor analysis to assess the fit of the model of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership positions.

Finally, Figure 6 shows us the second operationalization of the virtuous leadership model contributes to the criteria for social sustainability, in which the three factors and the elements that compose the model remain oriented in the same direction (configuration through positive covariance between them) with very significant statistical indices (low probability of occurrence by chance).

Figure 6.

Path diagram for the second-order factorial analysis of the model of virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace and intrinsic psychological well-being in a sample of work and organizational psychologists and people in leadership functions. Legend: Factor LS (Latent factor of the virtuous leadership model contributes to the criteria for social sustainability; LVQ (Factor 1); DQ (Factor 2); and IPWB (Factor 3).

In light of the results, a model for virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability can be proposed. This model should be based on a behavioral structure that defines its key variables, the instruments for measuring them, and through this framework—supported by other findings and theoretical principles in the field—provides insights to guide the organizational management based on specific needs.

5. Discussion

The aim of this research is to assess whether virtue-based ethical leadership, affective reactions towards people with disabilities in the workplace, and their intrinsic psychological well-being allow us to propose the existence of a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability.

Regarding the results obtained, at level one, the correlations between the 10 dimensions of the tests are statistically significant for 67% of the relationships analyzed (30 out of 45). However, the effect size is high in 16% (7 out of 45), moderate in 44.44% (20 out of 45), and low in 6.67% (3 out of 45). In this analytical context, hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 (significant relationship between virtuous leadership, intrinsic psychological well-being and affective reactions) would be met by reporting a statistically significant relationship of low and moderate impact in 25%, 75%, and 67% of the conditions analyzed, respectively.

These findings contribute to strengthening the empirical evidence provided by several studies that have linked diverse leadership models with an ethical-moral base (value-loaded) to followers’ psychological well-being and positive attitudes towards people with disabilities in the workplace, as well as with studies relating these two constructs. Furthermore, different authors propose that leaders that practice the principles of inclusion and positive influence create work environments that improve group well-being and cohesion (Shore & Chung, 2023), healthy and inclusive work climates (Johnson, 2021), which promote thriving (Newstead et al., 2020) and benefit the mental and social health of workers (Koenig et al., 2024). This phenomenon has also been reported in the scarce research on virtuous leadership, which associates employees’ well-being (Wang & Hackett, 2016; Hendriks et al., 2020), their affective experience (Abdelmotaleb & Saha, 2019), their happiness (Nassif et al., 2021), and the promotion of a healthy and inclusive work environment (Kenny & Di Fabio, 2024). The findings of this study specifically integrate the criteria for social sustainability into the study of leadership and the influence of interpersonal relationships in achieving the common good, with elements of moral legitimacy serving as a primary reference for activities within organizations (Melé, 2025). Therefore, this line opens up possibilities for new conceptual and empirical studies that further expand knowledge on sustainability from economic and environmental perspectives.

Considering the literature, although several types of value-loaded leadership could have similar effects on psychological well-being and attitudes towards individuals with disabilities in the workplace, virtuous leadership stands out due to its focus on excellence. It uses modeling to develop virtues across the entire organizational community, extrapolating them even beyond specific organizational frameworks (multiplier effect) and maximizing them in the long term. This approach clearly converges with a social sustainability-based approach.

At the second level, the hierarchical organization of the variables shows that the ten dimensions regrouped into five clusters explain 76% of the variance and are independent of each other. This allows for a more empirically supported evaluation of the fit of an explanatory model for a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria of social sustainability. In this case, hypothesis 4 would provide sufficient information for the assessment of this explanatory model, as it sequentially shows a trust-based virtuous leadership structure for obtaining results.

These findings strengthen the evidence about how positive leadership contributes to social sustainability, particularly in the case of value-loaded and virtue-based ethical leadership (Riggio et al., 2010; Ronda-Zuloaga, 2024). In this sense, leadership has been documented to be a key factor to promote employees’ well-being, prosocial behavior, and mental health (Das & Pattanayak, 2023). In connection, inclusion experiences rely on effective leadership (Randel et al., 2018) and, among other factors, on the promotion of favorable attitudes towards people with disabilities in the workplace (Papakonstantinou & Papadopoulos, 2019; D’Souza & Kuntz, 2023). In this line, enhancing psychological well-being and attitudes toward people with disabilities contributes to the social sustainability criteria (justice, integration, social well-being, inclusion, equity, social and human capital, mental and physical health and well-being, satisfaction, work well-being, among others; Fatourehchi & Zarghami, 2020).

Based on the above, at level three, the first- and second-order confirmatory factor analyses show efficient absolute, comparative, and parsimonious fits and an adequate estimation of the cross-validity indices of the proposed model for a type of virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability. Therefore, hypotheses 5 and 6 are met. After confirming the hypotheses, the virtuous leadership that contributes to the criteria for social sustainability can be operationalized (measured). This is a novel contribution to the scientific field of leadership research for the common good (which emphasizes the role of cooperative relationships in achieving institutional goals), with potential application in organizations (Melé, 2025).

Regarding the virtuous leadership type in a work environment, a model is proposed in which the virtue of justice (support for interpersonal relationships with a higher factor weight than prudence, fortitude, and temperance), intrinsic psychological well-being, and affective reactions towards people with disabilities can contribute to leaders promoting sustainable solutions through healthier organizational environments, the generation of positive relationships, trust, and a sense of achievement. This would aim to tackle the risks to mental health reported by the WHO and ILO (discrimination, inequality, excessive workload, and job insecurity) in different environments, which are associated with 15% of the work population being diagnosed with mental health disorders, 12 billion work days lost annually (due to anxiety and depression), and costs of up to one billion dollars to treat these disorders (Vásquez & Espinoza, 2024). Furthermore, these authors indicate that the American Psychiatric Association has reported that depression is the first cause of occupational disability and that 44% of work absenteeism (2021–2022) has mental health-related causes. Parallelly, the UK’s Mental Health Foundation has reported this phenomenon at 40%, which is three times more than the absenteeism due to work accidents. In turn, in Mexico, the WHO has revealed that at least 17% of workers will present a mental health disorder in their lives (and that only 20% will receive treatment), which will reach 25% in the world, with suicide as the second cause of death in the Z and millennial generations (representing 32.8% of the population; Stein, 2022) at a global level. In turn, Chile presents average suicide rates up to 8.5; 5.4 and 14.7 every 100,000 people in the 10–24, 10–19, and 20–24 age groups, respectively, for the period 2000–2017 (Araneda et al., 2021). In the workplace, according to official statistics, 61.4% of the expenses in occupational disability subsidies are concentrated on the diagnosis of mental health disorders, with 49.3% of medical leaves approved by health insurance companies (Superintendencia de Seguridad Social et al., 2023). In connection to this, according to the report on Work Security and Health, 67% of the occupational disease diagnoses in Chile correspond to mental health disorders (Superintendencia de Seguridad Social, 2023; Superintendencia de Seguridad Social et al., 2023). These data are complemented with data from the Mental Health Thermometer, which identified 24.8% of mental health problems in the Chilean population (Bravo et al., 2024).

With respect to the importance of leadership, Ronda-Zuloaga (2024) reports on the work published by Zak (2017) about the effects experienced by people who work at companies where there are high levels of trust, which are characterized by 74% less stress, a 104% increase in work energy, a 50% increase in productivity, 13% less days of sick leaves, 40% of workers reporting less tiredness, 76% showing more commitment, 29% increasing life satisfaction, and higher salaries on average. In turn, the author also refers to the work published by Frei and Morriss (2020), which indicates that companies with more trust have more profit.

In turn, the works by Vásquez and Espinoza (2024), Fernández-Gubieda & Bello (2023), and Ronda-Zuloaga (2024), propose that future topics associated with leadership in organizations are good work environment, sustainability, well-being, diversity, equity, inclusion, trust, crises management, good cooperative government, and organizational transformation processes, among others.

Considering the above, the results of this study, and previous evidence, positive leadership is important, especially virtuous leadership, to advance social sustainability and SDG achievement, particularly for numbers 3 (health and well-being, including mental health), 8 (growth through employment and decent work for everyone), 10 (reduction in inequalities when fighting discrimination of marginalized group), and 16 (fostering peaceful and inclusive societies, creating efficient, responsible and inclusive organizations).

From a practical perspective, the life cycle, formal education, and work-related training should be considered in order to propose strategies for the development of virtuous leadership. For organizations aiming to advance social sustainability through virtue ethics, it is recommended that they implement training and mentorship programs for leaders, value- and virtue-based cultural evolutions, virtue-based work profile design and leader selection, policies that provide organizational support to fair decision-making processes and fortitude, and systems to identify actions that promote inclusion and psychological well-being, among others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-J.R.-A. and P.L.-R.; Methodology, P.L.-R.; Software, P.L.-R.; Validation, P.L.-R.; Formal analysis, P.L.-R.; Investigation, M.-J.R.-A. and P.L.-R.; Resources, M.-J.R.-A.; Data curation, M.-J.R.-A. and P.L.-R.; Writing—original draft, M.-J.R.-A. and P.L.-R.; Writing—review & editing, M.-J.R.-A. and P.L.-R.; Supervision, M.-J.R.-A.; Project administration, M.-J.R.-A.; Funding acquisition, M.-J.R.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Office of the Vice- President Office for Research, Development and Innovation, University of Santiago of Chile. Grant number DICYT 032093RA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. The personal handling of the data was ethically guaranteed, and written informed consent was obtained, which was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee “Scientific Ethics Committee of the Vice-Rectorate for Re-search, Innovation and Creation of the University of Santiago de Chile, area of Social and Human Sciences”, Ethics report number 071/2020, Santiago, 26 March 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15167618.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ILO | International Labor Organization |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Abad, F., Olea, J., Ponsoda, V., & García, C. (2011). Medición en ciencias sociales y de la salud I. Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmotaleb, M., & Saha, S. K. (2019). Socially responsible human resources management, perceived organizational morality, and employee well-being. Public Organization Review, 20(2), 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, J. (2021). Psicometría. Disciplina de la medición en psicología y educación. Fondo Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., & Wilkins-Yel, K. G. (2021). Precarious work in the 21st century: A psychological perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araneda, N., Sanhueza, P., Pacheco, G., & Sanhueza, A. (2021). Suicidio en adolescentes y jóvenes en Chile: Riesgos relativos, tendencias y desigualdades. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ato, M., & Vallejo, G. (2015). Diseños de investigación en psicología. Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Batstone, D. (2003). Saving the corporate soul and (who knows?) Maybe your own. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein, D. L. (2019). The importance of work in an age of uncertainty: The eroding work experience in America. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, D., Errázuriz, A., Calfucoy, P., & Campos, D. (2024). Termómetro de la salud mental en Chile ACHS-UC: Novena ronda. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Centro UC y Asociación Chilena de Seguridad. Available online: https://encuestas.uc.cl/?p=2358 (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Bright, D. S., Winn, B. A., & Kanov, J. (2014). Reconsidering virtuous leadership: A study of character strengths in ethical leadership assessments. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 577–593. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J., Bezyak, J., Fraser, R. T., Pete, J., Ditchman, N., & Chan, F. (2013). Employers’ attitudes towards hiring and retaining people with disabilities: A review of the literature. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 19(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K. S. (2012). Positive leadership: Strategies for extraordinary performance. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, P., & García-Lombardía, P. (2011). Cómo desarrollar las competencias de liderazgo. EUNSA. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, P., & Wilkinson, H. (2009). Creciendo como líder. EUNSA. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Estudios Públicos. (2024). Estudio nacional de la opinión pública, encuesta CEP 92, Agosto-Septiembre 2024. Available online: https://www.cepchile.cl/encuesta/encuesta-cep-n-92/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Ciulla, J. B. (2014). Ethics, the heart of leadership. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional para la Implementación de la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS). (2023). Informe nacional voluntario sobre los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible en Chile 2023. Available online: https://www.chileagenda2030.gob.cl/recursos/1/documento/Informe_Voluntario_Cons-03_Junio2023.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Copeland, J., Chan, F., Bezyak, J., & Fraser, R. T. (2010). Assessing cognitive and affective reactions of employers toward people with disabilities in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalessandro, C., & Lovell, A. (2024). Workplace inclusion initiatives across the globe: The importance of leader and coworker support for employees’ attitudes, beliefs, and planned behaviors. Societies, 14(11), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. S., & Pattanayak, S. (2023). Understanding the effect of leadership styles on employee well-being through leader-member exchange. Current Psychology, 42, 21310–21325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2024). Human capital sustainability leadership and healthy organizations: Its contribution to sustainable development. In A. Di Fabio, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development in organizations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, O. N., & Kuntz, J. R. (2023). Examining the impact of reasonable accommodation appraisals on New Zealand managers’ attitudes toward hiring people with disability. Equality Diversity and Inclusion an International Journal, 42(6), 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadpoor, L., Lavasani, M. G., & Shahcheraghi, S. M. (2016). Relationship between perceived social support and psychological well-being among students based on mediating role of academic motivation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(3), 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensari, N., & Riggio, R. (2022). Exclusion of inclusion in leadership theories. In B. M. Ferdman, J. Prime, & R. E. Riggio (Eds.), Inclusive leadership transforming diverse lives, workplaces, and societies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fatourehchi, D., & Zarghami, E. (2020). Social sustainability assessment framework for managing sustainable construction in residential buildings. Journal of Building Engineering, 32, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdman, B. (2022). Inclusive leadership. The fulcrum of inclusion. In B. M. Ferdman, J. Prime, & R. E. Riggio (Eds.), Inclusive leadership transforming diverse lives, workplaces, and societies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Gubieda, S., & Bello, O. (2023). Sembrando la reputación. Conferencias de la international reputation week. EUNSA. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, N., Jenaro, C., Orgaz, B., & Martín-Cilleros, M. V. (2010). Understanding quality of working life of workers with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24(2), 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, F., & Morriss, A. (2020). Trust: The foundation of leadership. Leader to Leader, 2021(99), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, N., Deane, S., Hyseni, F., Soffer, M., Shaheen, G., & Blanck, P. (2024). Perceptions and bias of small business leaders in employing people with different types of disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 34(2), 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenleaf, R. K. (1982). The servant as leader. The Robert K. Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, R. D., & Wang, G. (2012). Virtues and leadership. Management Decision, 50(5), 868–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard, A. (2019). Del temperamento al carácter. Cómo convertirse en un líder virtuoso. EUNSA. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, M., Burger, M., Rijsenbilt, A., Pleeging, E., & Commandeur, H. (2020). Virtuous leadership: A source of employee well-being and trust. Management Research Review, 43(8), 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E., Linnerud, K., & Banister, D. (2014). Sustainable development: Our common future revisited. Global Environmental Change, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, I., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. (2024a). Seguridad y salud en el trabajo. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/temas/seguridad-y-salud-en-el-trabajo (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- International Labour Organization. (2024b). Trabajo decente. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/temas/trabajo-decente (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Jasper, C. R., & Waldhart, P. (2013). Employer attitudes on hiring employees with disabilities in the leisure and hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S. M., & Luthans, F. (2006). Entrepreneurs as authentic leaders: Impact on employees’ attitudes. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(8), 646–666. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. (2021). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership: Casting light or shadow. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]