1. Introduction

Template attacks were suggested by Chari et al. [

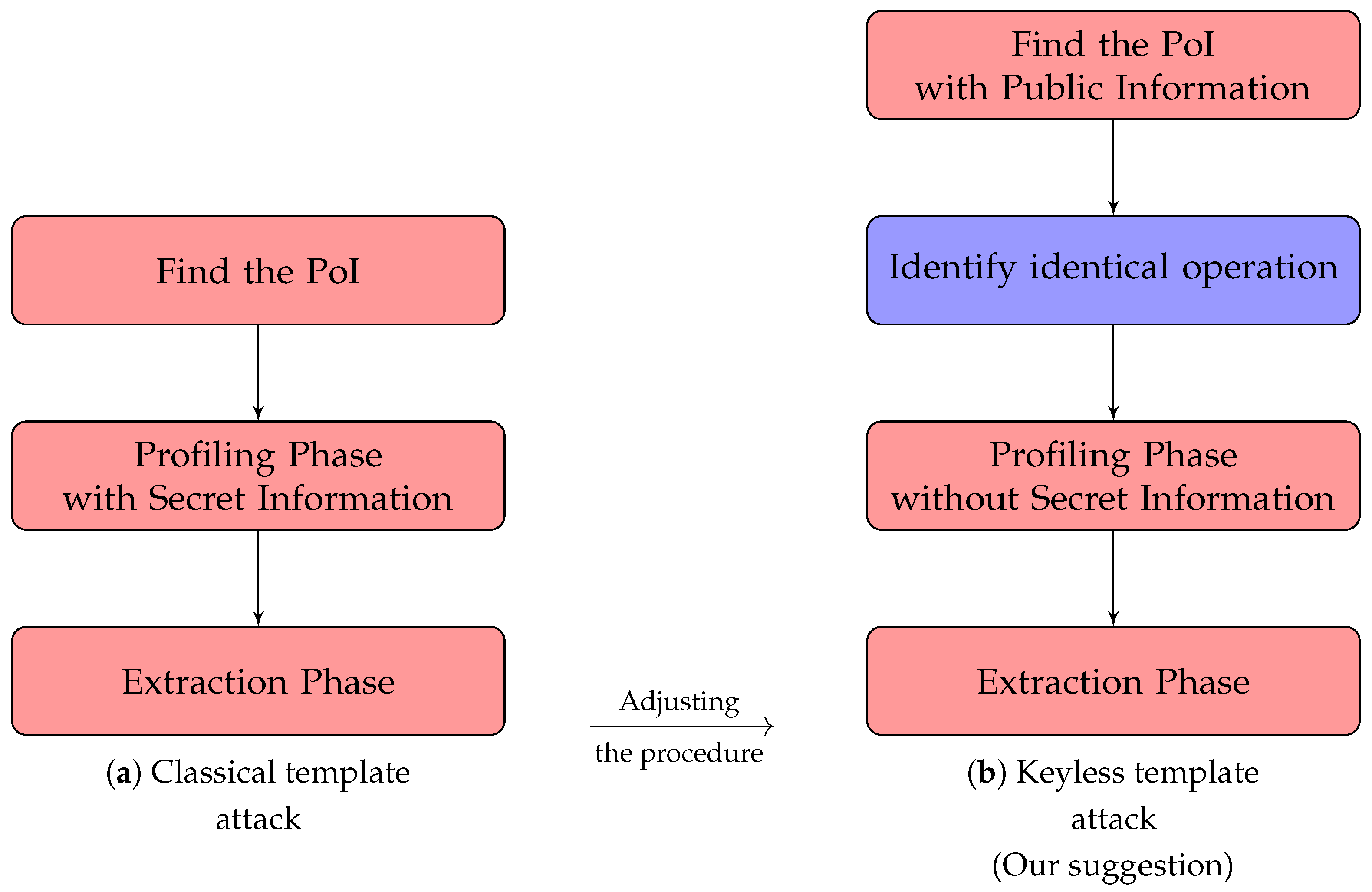

1] as one of the strongest side-channel attacks. In general, a template attack consists of two phases: profiling and extraction. To conduct template attacks, in the profiling phase, the attacker has to find the point of interest (PoI). Based on this information, templates are built using statistical tools or machine learning (ML). The significant aspect is that an adversary must have the knowledge of the secret information, such as the correct key, all instructions, and device specification. Afterward, based on its setting, the extraction phase is conducted to retrieve the correct key, with a different device.

To enhance the performance of template attacks, many contributions have been proposed. In order to find appropriate PoIs, statistical tools such as sum of squared pairwise T-difference (SOST) [

2], normalized inter-class variance (NICV) [

2], difference of mean (DOM) [

3], sum of squared difference (SOSD) [

2], signal to noise ratio (SNR) [

4], mutual information analysis (MIA) [

5], Komogorov-Smirnov analysis (KSA) [

6], and variance (VAR) [

7] have been suggested. Among these, the SOST tool is the most commonly employed to find PoIs.

In contrast, many researchers have struggled to construct an accurate leakage model. In terms of the (multivariate) Gaussian distribution model, there are some variants for covariance to improve the accuracy of prediction model. In particular, some proposals show remarkable results when applying the average to traces. Moreover, ML schemes, such as random forest, support vector machine, and self-organizing map [

8,

9], can be applied to build templates. Deep learning, convolutional neural networks, and multi-layer perception are also used to mount profiling attacks, based on artificial intelligence priciples.

Most template attacks including the profiling attacks are applied to the internal of encryption processes such as S-boxes. Therefore, some studies [

10,

11] try to overcome the masking countermeasures to apply profiling attacks. To return to key schedule sight, some papers [

7,

12,

13,

14] are applied to profiling attacks to extract round keys.

Related Works Sometimes, the key schedule can be the main target of side-channel analysis based on the profiling attack because the master key cannot usually be changed in attack device. Some papers [

7,

12,

13,

14] show that side-channel leakage can be extracted to acquire the master key or round key, when some operations are computed in a key schedule. The brief description is as follows.

E.Biham et al. [12] In software implementation of the smart card, they described that it is possible to recover the key value after producing some templates for each Hamming weight (HW) value of the key-dependent region. It is required to use a specific algorithm to distinguish the HW value of a key after collecting the different cryptographic key and fixed data, but they did not show the experimental results. That is, some ideas for side-channel analysis with respect to key schedules were just suggested.

P.N.Fahn et al. [13] Their main target was the exclusive or (XOR) operation of the round key when the cryptographic key is fixed. To obtain the round key, they first divided each round in a key schedule operation to observe the difference of the key bit. Subsequently, it was compared between each rounds. They confirmed that the difference which was found depends on the key bit when XOR operation is computed in each round.

S.Mangard [14] He proposed two strategies for a key schedule. In the first strategy, he learned the full leakages for round keys on another target. Subsequently, the round keys could be extracted on an attack target. In the second strategy, he referred that an adversary could learn the properties of HW for processing known values, such as plaintext/ciphertext on XOR operation, in the case that an adversary only had access to an attack target. However, he did not show the experimental results for the two strategies.

S. Mangard et al. [7] They summarized previous studies [

12,

13,

14] for the extraction of the secret information on the computation of a key schedule. Additionally, they confirmed that the HW of each data can be characterized by MOV instruction. To utilize its properties, they mentioned that round keys could be acquired to perform template attacks in key schedule.

Although the masking scheme of key schedule is suggested [

15], a part of loading and/or saving of the master key can be naturally leaked in terms of side-channel information. In other words, if the templates for natural loaded and/or saved master key can be built, it is possible that the correct key can be retrieved based on the assumption below.

Assumption 1 (Adversary Assumption for General Template Attack).

- 1.

An adversary obtains an identical device as a target device.

- 2.

An adversary fully controls the device that has identical instructions as the target device.

- 3.

For the abovementioned instructions, an adversary can execute the device with different data and different keys to collect numerous traces.

Since an adversary can build an accurate leakage model, this assumption is ideally expected to acquire higher performance compared to non-profiling schemes. Surprisingly, there are no challenges in the elimination of an adversary assumption. Additionally, if the encryption/decryption parts include the strong countermeasures, such as high-order masking [

16], hiding [

17], and the combination between high-order masking and hiding [

18], it is hard to recover the secret information. Naturally, we can imagine two fold. The first thing is that the countermeasures of encryption/decryption parts are very powerful to break secret information. The second thing is that the master key is loaded and/or saved to a local variable to operate key schedule operation, and also plaintext/ciphertext is loaded/saved to a local variable, respectively. This is a reasonable assumption owing to the fact that many countermeasures concentrate on depening the encryption/decryption parts rather than the key schedule. Even though the masking countermeasure is applied to key schedule operation, the loading/saving of the master key naturally might be leaked.

Challenge & Contribution An adversary should acquire the identical device in order to build the templates in the profiling scenario. If an adversary creates the templates without identical devices, the template attacks will be more attractive compared to non-profiling attacks. But, how can we create templates in a non-profiling scenario? The answer is that we can utilize public information such as plaintext and ciphertext. Then, PoIs can easily be found without secret information. Afterward, the templates can be built. Despite this fact, in usual scenarios, the templates are only used to recover the public information, not secret, due to the fact that the templates are built from public information. From a different angle of view, in this paper, we utilize the template created from public information to the key schedule operation, which is composed of secret information. More precisely, after searching the loading/saving parts in public and secret information, we can apply the templates to the secret information part. Additionally, although assuming that an adversary cannot recover any secret information in encryption/decryption parts, our suggestion allows us to recover the secret key.

While performing our suggestion, the trace points used in the profiling phase might not be identical to those used in the extraction phase. To resolve this issue, we should estimate the statistical difference between the traces used in the profiling and extraction phases, before executing the extraction phase. Intuitively, the success rate seems to depend on the statistical difference. In this paper, we show the possibility of our suggestion, which means that the template attack from the fact that the profiling is created by only the public information is feasible.

In generic non-profiling attacks, the key schedule operation of a block cipher cannot be targeted since all intermediate variables in the key schedule operation cannot be changed. However, even though we do not employ the original profiling concept, the Hamming weight (HW) information can be recovered on key schedule operation. When performing a template attack to create the templates, we can utilize public operations like plaintext or ciphertext. In other words, while the plaintext or ciphertext are moved to the local variables, the templates can be constructed. Despite the mitigated assumption, the success rate is quite high when the power consumption model is considered as a HW model. After the HW value of the secret key is recovered using our suggestion, we can employ an attack scheme like an algebraic attack to completely retrieve the master key. Consequently, by our suggestion, the master key is directly retrieved in the key schedule operation without assuming an original profiling attack. In this paper, to show our suggestion, we decide the main target as the key schedule of a block cipher Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) [

19].

2. Classical Template-Based Simple Power Analysis

In this section, we briefly discuss the template attack with respect to profiled side-channel analysis. Before presenting a detailed description of a template attack and our suggestion, we first summarize the notations used, as in

Table 1. Note that the notations described in this section are maintained for consistency and used throughout the rest of this paper.

An adversary accesses an identical cryptographic device that he/she can program to his/her selection via template attack [

1]. Soon afterward, many researchers conducted studies to enhance the template attack. Based on this fact, the typical procedure to perform a template attack is as follows.

Find the PoIs

Profiling Phase

Extraction Phase

Before explaining our suggestion, we conducted a classical template-based simple power analysis (SPA) on a key schedule of the block cipher AES that was comparable to the success rate of an attack of our suggestion. For this, some variables for each step were selected as follows.

2.1. Find the PoIs

As previously stated, many selection schemes were proposed. Our main focus is not the improvement of the efficiency but the examination of the possibility of an attack. Therefore, we chose a generic approach to select a PoI. Owing to the fact that the SOST tool is commonly used to find the PoI, we employ this tool.

2.2. Profiling Phase

To improve the success rate of a template attack, we use the HW value as an intermediate variable. Moreover, to reduce the complexity of the intermediate variable, we only consider 8-bits as the size of the operand size in CPU. Namely, the number of templates is 9 classes.

2.3. Extraction Phase

As Choudary et al. warned in Reference [

20], while avoiding the floating-point limitation and numerical problems for a large matrix size, we carefully compute an original multivariate normal distribution to obtain the HW value as follows.

4. Experiment Results

Before applying our approach, we first perform the template attack on the saving of plaintext in order to investigate the performance of the classical template-based SPA. Of course, the classical template attack can be applied to the saving of master key after collecting the traces while changing the master key. However, we can confirm whether the template attack works or not in the operation of public information such as plaintext and ciphertext if the master key cannot be changed. Hence, to perform classical template-based SPA, the main target is considered as the saving of plaintext in this section. Furthermore, we explain how to apply our approach in a key schedule after confirming the performance of classical template-based SPA. As described beforehand, the difference between classical template-based SPA and our approach is extraction phase and “Identify idential operation” step is also required. For applying our proposal, assuming that there is no countermeasure when the saving the plaintext and the saving the master key in a key schedule operation of the block cipher AES. All results are supported by ChipWhisperer-Lite (CW1173) [

22], which is based on an AVR chip.

4.1. Result of Classical Template-Based Simple Power Analysis

In this section, to confirm the performance of a classical template-based SPA, we conducted a classical template-based SPA while loading the plaintext. This result allows us to compare the our suggestion.

(1) Finding the point of interest (PoI)

In

Figure 2, 16 bytes might be moved to the local variables, owing to the fact that there are 16 patterns. Moreover, we confirm the PoIs using SOST tool.

In

Figure 3, the information about plaintext is split into three areas: Area (1), Area (2), and Area (3). However, we only utilize Area (1) because Area (2) and Area (3) might change due to some reasons such as a change in the implementation method. In other words, Area (1) can be always assumed to occur because the plaintext is stored in the local variables of the internal function.

(2) Profiling Phase

As previously stated, we utilized the HW value as the power consumption model. To build the templates, 100∼1000 traces were used for each HW value.

(3) Extraction Phase

We re-collected the traces to perform a template-based SPA on the plaintext operation of the block cipher AES. In addition, to measure the performance of a template attack, we employ a security metric as the guessing entropy [

5]. The experimental variables are presented in detail in

Table 2.

In the experimental variable of the profiling phase, a maximum of 1000 traces were used for each HW value. That is, a total of 9000 traces were utilized to build the templates.

As shown in

Figure 4, most HW values of each byte have been recovered. Moreover, only the best result is represented corresponding to the number of traces for the extraction phase. Except for two bytes, 14 bytes are easily extracted when performing a classical template-based SPA. Moreover, the guessing entropy of two bytes is two. Therefore, it is not difficult to recover the master key.

4.2. Result of Keyless Template-Based Simple Power Analysis

While all existing template attacks assume that an adversary acquires identical device that is different from the target device, in our proposal, we can eliminate it. Based on the above fact and

Figure 1, we show how apply our approach to a key schedule.

(1) Finding the PoI with Public Information

In the first step, we should find the PoI with only public information which is different from the points used for extraction phase. As explained earlier, the saving of the plaintext is employed to create the templates, which is referred to

Figure 2. In other words, the templates already created in classical template-based SPA can be utilized to our approach.

(2) Identifying identical operation

As shown in

Figure 5, red boxes in each figure seem to show similar operations. More precisely, as previously stated, this is easily confirmed to use the relevant statistical tool in

Figure 5. However, we might not be able to completely identify how operations are calculated from

Figure 5 below. Therefore, in order to distinguish our target in the figure below, another statistical tool or function is required. Actually, the auto-correlation tool is used in order to distinguish the loading of plaintext and master key. The last condition which is analogous to the original assumption is the third condition of Assumption 1.

As seen in

Figure 6, we easily identified the operation that is similar to loading the plaintext. In addition, to compute

, we employed autocorrelation. As a result, the matching rate acquires more than 0.9. That is, the calculation of

was not required. Using Equation (1), we obtained the following expression.

where

specifies the identity function.

(3) Profiling Phase

The hyper-parameter setting is identical to

Table 2. The points to create templates for each HW values are also considered as the Area (1) in

Figure 3.

(4) Extraction Phase

Similar to previous results in

Section 4.1, the best result is represented corresponding to the number of traces used in the extraction phase. The results can be explained through categorization into three groups. In the first group, the guessing entropy converges to 1. Namely, half out of 16 bytes can be completely recovered using our suggestion. Moreover, in the second group, the recovered value is about 2, even though the HW value cannot be definitely retrieved. A few bytes have about guessing entropy 3 in the last group.

Although all bytes cannot be retrieved, a brute force attack can be performed based on the recovered HW value. Moreover, to examine the detailed results, we compare the classical and keyless template-based SPAs in terms of the number of PoIs.

4.3. Comparison between Classical and Keyless Template-Based Simple Power Analysis

To investigate the detailed results, only three cases are represented in this section because we have categorized into three groups in the previous section. In addition, to investigate the effect of the number of PoIs, the results are plotted when the number of PoIs is the range 1–20. That is, the 1st, 10th, and 15th bytes are represented.

In the classical template-based SPA for the 1st byte, the partial guessing entropy (PGE) converges to 1, regardless of the number of traces used in the profiling and extraction phases. However, in terms of our suggestion, all results in

Figure 7d are poor. Unlike the result for the 1st byte, the HW value is completely recovered by our suggestion in

Figure 7e. However, contrary to the result of the classical template-based SPA, the performance of our suggestion seems to be better. In the 15th byte result of the classical template-based SPA, the PGE decreases corresponding to the number of traces used in the profiling and extraction phases. This is the most reasonable result in our experiment. In addition, in our opinion, this result is worse than that of the classical template-based SPA but the PGE still maintains a low value.

Unlike to the result of the single PoI, all results from our proposed approach are less than the classical template-based SPA in

Figure 7. This indicates that the serious points cannot be matched with traces used in the profiling phase and that used in the extraction phase, as the number of PoIs increases. Especially, in

Figure 8e, we could not retrieve the HW value of the secret key, as we did in the classical template-based SPA. In other words, we should study the performance of a template attack when the number of PoIs is very small to improve our suggestion.

4.4. Analysis and Discussion

The analysis and discussion of our results and approaches can be divided into three parts in this section. First, the attack complexity is still high, despite our proposal. As J. VanLaven et al. already mentioned in [

23], the maximum attack complexity of retrieving the master key is roughly

, although the HW of master key is revealed. However, its restriction can be overcome utilizing their proposal which the known HW round key can be compared to unknown HW round key. In other words, the unknown HW round key can be distinguished by comparing known HW value using statistical tools such as Euclidean distance. Even if the comparison between the known value and unknown value has some error, they demonstrated that it is feasible. Further, the master key can be decided as a unique key with the pair for plaintext and ciphertext.

The second thing is that our result might look to be obscure. As mentioned previously, we have only represented the best results in many parameter settings. In

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the number of profiling traces is rarely dependent on the final PGE. Hence, the consideration for the number of profiling traces while building the templates is not required. Moreover, half of PGE results are obtained when the number of PoIs is 1. Even if the remaining results are spread to various PoIs, the PGE rapidly reaches 1. The HW of the incorrect key is not stable enough to reach PGE 1 despite using many attack traces. In other words, the complexity does not affect the feasibility even though many parameter settings are performed in our suggestion.

The last thing is the potential for our suggestion. In

Figure 6, the result is naturally worse than the original attack which is referred to in

Section 4.1. The reason for this is that the worse result is the difference of the original template attack. In other words, the maximum possibility of our approach is restricted to the performance of the original scheme. Despite its limit, our approach can be applied to the case that it is impossible to perform the template attack and there are strength countermeasures in the encryption/decryption process. Furthermore, template attack has been studied in many papers to improve efficiency and performance, which are naturally applied to our approach. Also, recent works such as machine learning are perhaps applicable to our study.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the effort to eliminate the profiling assumption is worthwhile because most of the HW value in the AES key schedule operation can be recovered. In other words, by introducing our new approach with an adjustment of the procedure of template attacks, we can provide a more reasonable system. Additionally, our suggestions still allow us to reveal the secret information in the key loading part, even though numerous countermeasures are applied to an encryption/decryption process. To the best of our knowledge, this suggestion is a first attempt ofsuch. As mentioned above, we have concentrated only on the potential possibility of the template attack.

As an example, we have studied the attack on an AES key schedule operation. In classical template attacks, most HW values of the master key can be easily retrieved, but an adversary should know the secret information to build the templates. However, our suggestion can yield a reasonable recovery of the master key even though the performance cannot outperform the original methods used in such attacks. In other words, our new approach of eliminating profiling assumptions can be used in practice to retrieve a master key in a suitable timeframe. It is necessary to further verify our new approach in other template attack schemes and encryption operations.