Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in Thermally Improved Residential Buildings, with a Weather Controlled Central Heating System. A Case Study in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- 33–60% to reduce energy consumption by improving thermal insulation of walls,

- 16–21% for the modernization of the ventilation system,

- 14–20% to improve the thermal insulation of the window joinery,

- 10–12% for regular inspections and modernization of central heating boilers.

- quantitative regulation, consisting in adjusting, depending on the individual thermal needs of the user of the premises, the amount of the flowing heating medium in the system without changing its temperature, e.g., by an appropriate setting on the thermostatic valve head,

- quality regulation, which consist in changing the temperature of the heating medium with its constant flow through the installation.

2. Literature Review and Justification of Topic Selection

3. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- after thermal improvement, where the energy saving in percent is calculated according to equation:

- (b)

- after the introduction weather controlled central heating system.

- Building A. As the system was installed in September 2013, the first period with a full 12-month cycle, from January to December, included in the savings analysis, is 2014.

- Building B. As the system was installed at the beginning of January 2015, the first period with a full 12-month cycle, from January to December, included in the savings analysis, is 2015.

- Building C. As the system was installed in September 2012, the first period with a full 12-month cycle, from January to December, included in the savings analysis, is 2013.

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamczyk-Królak, I. Analysis of Heat Energy Savings in Single-Family Housing. Constr. Optim. Energy Potential (CoOEP) 2014, 1, 9–14. Available online: http://www.bozpe.bud.pcz.pl/ANALYSIS-OF-HEAT-ENERGY-SAVINGS-IN-SINGLE-FAMILY-HOUSING,91052,0,2.html (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- European Commission. Energy Consumption by End-Use in Residential Buildings. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/content/energy-consumption-end-use_en (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Lis, P.; Sekret, R. Efektywność Energetyczna Budynków-Wybrane Zagadnienia Problemowe. Rynek Energii 2016, 6, 29–35. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-dcd9364e-6cc9-427e-b150-3fbae739f649?q=bwmeta1.element.baztech-a4741551-e340-47a9-887d-714a9ba80911;4&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- European Environment Agency. Achieving Energy Efficiency Through Behaviour Change: What does It Take? EEA Technical Report No 5/2013. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/achieving-energy-efficiency-through-behaviour/file (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Caniato, M.; Gasparella, A. Discriminating People’s Attitude towards Building Physical Features in Sustainable and Conventional Buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sant’Anna, D.O.; Dos Santos, P.; Vianna, N.; Romero, M. Indoor environmental quality perception and users’ satisfaction of conventional and green buildings in Brazil. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz-Lovera, C.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J.; De La Cruz-Fernández, J.-L.; Montoya, F.G.; Alcayde, A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Analysis of Research Topics and Scientific Collaborations in Energy Saving Using Bibliometric Techniques and Community Detection. Energies 2019, 12, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leaman, A.; Bordass, B. Are users more tolerant of ‘green’ buildings? Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szul, T. Energy Efficiency Assessment of Buildings; Scientific Publishing House INTELLECT: Waleńczów, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-950526-3-7. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Noga, M.; Ożadowicz, A.; Grela, J. Efektywność Energetyczna i Smart Metering–nowe Wyzwania dla Systemów Automatyki Budynkowej. Napędy Sterow. 2012, 12, 54–59. Available online: http://beta.nis.com.pl/userfiles/editor/nauka/122012_n/Oadowicz_12-2012.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Szul, T.; Kokoszka, S. Application of Rough Set Theory (RST) to Forecast Energy Consumption in Buildings Undergoing Thermal Modernization. Energies 2020, 13, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BPIE; Staniaszek, D.; Firląg, S. Financing Building Energy Performance Improvement in Poland. StatusReport. Available online: http://bpie.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BPIE_Financing-building-energy-in-Poland_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Adamczyk, J.; Dylewski, R. Ecological and Economic Benefits of the “Medium” Level of the Building Thermo-Modernization: A Case Study in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathirgamanathan, A.; De Rosa, M.; Mangina, E.; Finn, D.P. Data-driven predictive control for unlocking building energy flexibility: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, T. The Energy Efficiency Potential of Intelligent Heating Control Approaches in the Residential Sector; Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://sustec.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/mtec/sustainability-and-technology/PDFs/130420%20Master%20thesis%20on%20intelligent%20heating%20control%20approaches%20-%20Thomas%20Kasper_final.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Persson, J.; Vogel, D. Utnyttjande av Byggnaders Värmetröghet. Utvärdering av Kommersiella Systemlösningar; Lunds Universitet: Lund, Sweden, 2011; ISRN LUTVDG/TVIT--11/5030--SE(68); Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=3161459&fileOId=3161460 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Herrlin, E. Alternativa Reglermetoder för en Energieffektiv Byggnad; KTH Skolan för Kemi Och Hälsa: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017; Available online: http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1143765/FULLTEXT02.pdf. (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Enreduce Energy Control AB. Available online: https://www.enreduce.se/om-oss/ (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Oldewurtel, F.; Parisio, A.; Jones, C.; Gyalistras, D.; Gwerder, M.; Stauch, V.; Lehmann, B.; Morari, M. Use of model predictive control and weather forecasts for energy efficient building climate control. Energy Build. 2012, 45, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilding, O.; Nilsson, S. Analysis and Development of Control Strategies for a District Heating Central; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2009; Available online: http://publications.lib.chalmers.se/records/fulltext/99408.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Cox, R.A.; Drews, M.; Rode, C.; Nielscen, S.B. Simple future weather files for estimating heating and cooling demand. Build. Environ. 2015, 83, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabona, Ecopilot. Available online: https://nordomatic.com/building-automation/ecopilot/ (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Egain Edge. Available online: https://www.egain.io/pl/nasz-platforma/technologia/#sztuczna-inteligencja (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Adamski, M.; Ruszczyk, J. New Weather Controlled Central Heating System. Ciepłownictwo Ogrzew. Went. 2012, 43, 278–283. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299447251 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Bacher, P.; Madsen, H.; Nielsen, H.A.; Perers, B. Short-term heat load forecasting for single family houses. Energy Build. 2013, 65, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warfvinge, C.; Dahlblom, M. Projektering av VVS-Installationer; Studentlitteratur AB: Lund, Sweden, 2010; ISBN 978-914-405-5619. [Google Scholar]

- Zemann, C.; Deutsch, M.; Zlabinger, S.; Hofmeister, G.; Gölles, M.; Horn, M. Optimal operation of residential heating systems with logwood boiler, buffer storage and solar thermal collector. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 140, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, L.; Hu, E. A neural network-based multi-zone modelling approach for predictive control system design in commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2015, 97, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigler, J.; Prívara, S.; Váňa, Z.; Žáčeková, E.; Ferkl, L. Optimization of Predicted Mean Vote index within Model Predictive Control framework: Computationally tractable solution. Energy Build. 2012, 52, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Ma, R.; Deng, Y. Identification of the optimal control strategies for the energy-efficient ventilation under the model predictive control. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W. Performance of ANN-based predictive and adaptive thermal-control methods for disturbances in and around residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2012, 48, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietaharju, P.; Ruusunen, M.; Leiviskä, K. Enabling Demand Side Management: Heat Demand Forecasting at City Level. Materials 2019, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bröms, G.; Isfält, E. Effekt-och Energibesparing Genom Förenklad Styrning och Drift av Installationsystem i Byggnader. Sztokholm: Institutionen Förinstallationsteknik, KTH, ISSN: 0284-141X. 1992. Available online: https://www.kabona.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Sammanfattning_teoretisk_bakgrund_Ecopilot.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Szul, T.; Nęcka, K.; Mathia, T. Neural Methods Comparison for Prediction of Heating Energy Based on Few Hundreds Enhanced Buildings in Four Season’s Climate. Energies 2020, 13, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, J. Cała prawda o budynkach wielkopłytowych. Przegląd Bud. 2012, 83, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dohojda, M.; Wiśniewski, K. Termomodernizacja sposobem rewitalizacji osiedli mieszkaniowych z wielkiej płyty. Przegląd Bud. 2019, 90, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- CEN. European Standard: Heating Systems in Buildings. PN-EN ISO 12831-1:2017-08. 2017. Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-12831-3-2017-08e.html (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- CEN. European Standard: Energy Performance of Buildings-Calculation of Energy Use for Space Heating and Cooling. ISO 13790:2008. 2008. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/41974.html (accessed on 5 October 2020).

| Heating Control System in Objects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Specification | Egain Edge | EnReduce | Kabona |

| number of buildings tested | 19; 2 | 7 | 4 |

| range of energy savings achieved % | 0–26; 13,7–14 | 7–20 | 9–16 |

| average energy saving % | 11; 13,85 | 13 | 13 |

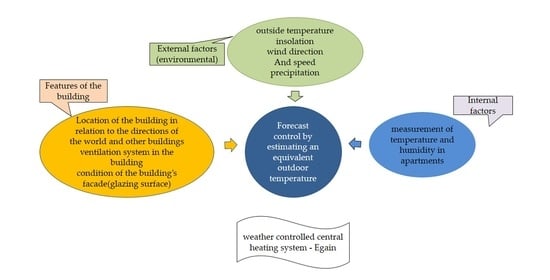

| Parameters Taken into Account by the Heating Control System | Forecasting Regulation Egain Edge | Weather Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| External factors (environmental) | outside temperature | x | x |

| insolation | x | - | |

| wind direction and speed | x | - | |

| precipitation | x | - | |

| Features of the building | location of the building in relation to the directions of the world and other buildings | x | - |

| ventilation system in the building | x | - | |

| condition of the building’s facade (glazing surface) | x | - | |

| amount of water in the central heating system | x | - | |

| shape and height of the building | x | - | |

| Internal factors | measurement of temperature and humidity in apartments | x | - |

| Building Condition | Building | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| before modernization, [year] | 10 | 12 | 9 |

| after thermal improvement, [year] | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| after the introduction weather controlled central heating system, [year] | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| No. | Parameter | Abbreviation | Building | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||

| 1 | construction year of a building, [year] | CA | 1984 | 1992 | 1994 |

| 2 | year in which the thermal improvement was performed, [year] | Cti | 2012 | 2014 | 2011 |

| 3 | year in which the installing weather controlled central heating system, [year] | Chs | 2013 | 2015 | 2012 |

| 4 | calculated from exterior measurements the heated volume of building, [m3] | Ve | 9876 | 10294 | 18376 |

| 5 | calculated from interior measurements total (net internal area), [m2] | Ain | 2231 | 1646 | 3572 |

| 6 | calculated surface of heated floors from interior measurements, [m2] | Af | 1576 | 1051 | 2235 |

| 7 | calculated from exterior measurements surface of roof projection area (net), [m2] | Ar | 602 | 869 | 1141 |

| 8 | calculated from exterior measurements total walls’ surface (net) area, [m2] | Aw | 1560,1 | 1417,3 | 2762,3 |

| 9 | calculated surface of floor from interior measurements (floor over basement or floor on the ground), [m2] | Afl | 446 | 549 | 714 |

| 10 | calculated from exterior measurements total windows area, [m2] | Atw | 383,5 | 272,5 | 742,2 |

| 11 | number of storeys, [pc.] | NOs | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| 12 | number of residential flats, premises [pc.] | NOp | 45 | 30 | 75 |

| 13 | number of living persons per building [Nb] | NOpb | 145 | 99 | 195 |

| 14 | shape coefficient of buildings (the ratio surface to volume), [m2∙m−3], [m−1] | S/Ve | 0,37 | 0,36 | 0,38 |

| 15 | calculated thermal transmittance of walls components before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uw0 | 0,57 | 0,44 | 0,36 |

| 16 | calculated thermal transmittance of peak walls components before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Upw0 | 0,56 | 0,49 | 0,33 |

| 17 | calculated thermal transmittance of roof projections components before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Ur0 | 0,49 | 0,2 | 0,18 |

| 18 | calculated thermal transmittance of floor components on the ground before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Ug0 | 3,19 | 3,03 | 3,23 |

| 19 | calculated thermal transmittance of floors components (floor over basement) before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uf0 | 1,37 | 0,74 | 0,39 |

| 20 | thermal transmittance of windows (commercial data) before modernization, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uwin0 | 2,6 | 2 | 2 |

| 21 | calculated thermal transmittance of walls components after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uw1 | 0,24 | 0,22 | 0,19 |

| 22 | calculated thermal transmittance of peak walls components after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Upw1 | 0,26 | 0,23 | 0,19 |

| 23 | calculated thermal transmittance of roof projections components after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Ur1 | 0,18 | 0,2 | 0,18 |

| 24 | calculated thermal transmittance of floor components on the ground after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Ug1 | 3,19 | 3,03 | 3,23 |

| 25 | calculated thermal transmittance of floors components (floor over basement) after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uf1 | 1,37 | 0,74 | 0,39 |

| 26 | thermal transmittance of windows (commercial data) after thermal improved, [W∙m−2·K−1] | Uwin1 | 1,4 | 1,4 | 1,4 |

| 27 | calculated time constant, [h] | τ | 78 | 62 | 84 |

| 28 | calculated heating consumed power, [kW] | Φh | 154 | 125 | 236 |

| 29 | calculated temperature of the internal wall surface before modernization, [°C] | Tiwb | 16 | 16,91 | 17,47 |

| 30 | calculated temperature of the internal wall surface after thermal improved, [°C] | Tiwa | 18,32 | 18,46 | 18,67 |

| 31 | measured, (average) index of final energy demand for heating converted to the conditions of the standard heating season, before modernization, [kWh∙m−2·year−1] | FE0(avg) | 95,4 | 104,0 | 102,9 |

| 32 | measured, index of final energy demand for heating converted to the conditions of the standard heating season, after thermal improved, [kWh∙m−2·year−1] | FE1 | 74 | 77,6 | 95,3 |

| FE%,ES,a | Building | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| savings achieved, % | 22,5 | 25,4 | 7,4 |

| Year | Building | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||||

| ∆FE,ES,b,i [kWh∙m−2·Year−1] | FE%,ES,b,i % | ∆FE,ES,b,i [kWh∙m−2·Year−1] | FE%,ES,b,i % | ∆FE,ES,b,i [kWh∙m−2·Year−1] | FE%,ES,b,i % | |

| 2013 | 7,3 | 7,7 | ||||

| 2014 | 16 | 21,6 | 28,4 | 29,9 | ||

| 2015 | 18,6 | 25,3 | 9,3 | 12 | 38,1 | 39,9 |

| 2016 | 18,1 | 24,5 | 12,4 | 15,8 | 34,2 | 35,9 |

| 2017 | 12,4 | 16,7 | 7,2 | 9,3 | 35 | 36,8 |

| 2018 | 20,3 | 27,6 | 16,9 | 21,8 | 36,1 | 37,9 |

| 2019 | 19,5 | 26,3 | 17,3 | 22,3 | 37,8 | 39,8 |

| average | 17,5 | 23,6 | 12,6 | 16,2 | 30,9 | 32,5 |

| FE%,ES,tot | Building | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| total savings achieved, % | 40,7 | 37,5 | 37,5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cieśliński, K.; Tabor, S.; Szul, T. Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in Thermally Improved Residential Buildings, with a Weather Controlled Central Heating System. A Case Study in Poland. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238430

Cieśliński K, Tabor S, Szul T. Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in Thermally Improved Residential Buildings, with a Weather Controlled Central Heating System. A Case Study in Poland. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(23):8430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238430

Chicago/Turabian StyleCieśliński, Krzysztof, Sylwester Tabor, and Tomasz Szul. 2020. "Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in Thermally Improved Residential Buildings, with a Weather Controlled Central Heating System. A Case Study in Poland" Applied Sciences 10, no. 23: 8430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238430

APA StyleCieśliński, K., Tabor, S., & Szul, T. (2020). Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in Thermally Improved Residential Buildings, with a Weather Controlled Central Heating System. A Case Study in Poland. Applied Sciences, 10(23), 8430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238430