Abstract

The amount of fraud on the Internet is increasing along with the availability and the popularity of the Internet around the world. One of the most common forms of Internet fraud is phishing. Phishing attacks seek to obtain a user’s personal or secret information. The variety of phishing attacks is very broad, and usage of novel, more sophisticated methods complicates its automated filtering. Therefore, it is important to form up-to-date and detailed phishing attack taxonomy, which could be used for both human education purposes as well as phishing attack discrete notation. In this paper, we propose an e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy, which includes six phases of the attack. Each phase has at least one criterion for the attack categorization. Each category is described, and in some cases the categories have sub-classes to present the full variety of phishing attacks. The proposed taxonomy is compared to similar taxonomies. Our taxonomy outperforms other phishing attack taxonomies in numbers of phases, criteria and distinguished classes. Validation of the proposed taxonomy is achieved by adapting it as a phishing attack notation for an incident management system. Taxonomy usage for phishing attack notation increases the level of description of phishing attacks compared to free-form phishing attack descriptions.

1. Introduction

The development of information technologies brings many benefits to people and businesses. At the same time, information technology serves as a gateway for criminal activities. While hacking or malware usage is a specific skill, requiring activities and not executed by an ordinal person, the field of social engineering is not so technically demanding. Therefore, the popularity of social engineering attacks is on the rise. In the third quarter of 2019, social engineering attacks were the number one threat for individual users and number two for organizations [1]. Social engineering, in most cases, is the initial phase for the next cybercrime steps. “In 81 percent of cases, malware infections of corporate infrastructure started with a phishing message” [1].

A phishing attack is a social engineering attack aimed at fraudulently acquiring private and confidential information from intended targets [2]. A phishing attack might use different communication channels, and the most common are e-mail messages, phone calls, messages in social networks and others. It is very important to identify phishing messages to fight phishing and mitigate the leading cybercrime. While technical anti-phishing solutions are not accurate enough, the education and understanding of the phishing attack landscape is very important to ensure personal and organizational security. In this paper, we focus on e-mail-based phishing attacks. In an e-mail-based phishing attack, e-mail messages used as a contact environment to the victim to obtain targeted information. E-mail-based phishing attacks were selected as this is the most popular environment for phishing messages, and e-mail messaging is vulnerable to spoofing and e-mail address camouflage methods. E-mail messages are not in real-time; therefore, victims are motivated to act without questioning.

This paper aims to highlight the variety of e-mail-based phishing attacks by proposing an e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy. The proposed taxonomy concentrates on e-mail-based phishing attack specifically and includes e-mail address gathering techniques and e-mail sender address classification. There are specific e-mail-based phishing attack classifications, while the rest of the taxonomy can be applied to a wider range of phishing attacks. We also do not analyze person-to-person phishing attack peculiarities, which are more common when instant messaging or live communication is used.

In the second section, we overview existing methods for presentation of the phishing attack taxonomies. The content of the existing scientific papers on e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomies is summarized in the second section as well. The proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy is presented with each phase, criterion and class of the taxonomy in Section 3. To validate the proposed taxonomy, it is compared to existing phishing attack taxonomies. On top of that, the taxonomy is adapted for phishing attack notation used in an incident management system. The flow and the results of this validation are presented in Section 4.

2. Related Works

Taxonomy is a systematic, object-based approach to categorize various criteria into classes. The quality of the taxonomy depends on its ability to present the full landscape (existing categorization criteria and their classes) of the object, as well as clear description and presentation.

2.1. Visualization Forms of Phishing Attack Taxonomies

For subject-based classification, different approaches to describing subjects exist [3]. Taxonomy is one of the most used approaches for cybercrime subject representation. It allows term hierarchy representation and is suitable for indexing content, exploratory search and browsing [4].

Proper taxonomy presentation increases its perception and understanding of the overall view. The simplest solution to present taxonomy is a textual description of objects’ classification criteria and the classes that the object belongs to. This solution is very suitable for small taxonomies. Yeboah-Boateng and Amanor [5] presented taxonomy for threats against mobile devices. There are only three categories (Phishing, SMiShing and Vishing). It would not be beneficial to look for another, more complex form to present the taxonomy, as only three categories are detailed. In cases with several levels of classes or multiple classification criteria, lists and/or tables are used to present the structure of the taxonomy. In the taxonomy of behavior of malware [6], existing categories in works of other authors are presented as lists, while the proposed taxonomy is presented as a table to illustrate the possible behavior of four classes (evasion, disruption, modification and stealing). Miloslavskaya et al. [7] use the table format to present a taxonomy of unsecured digital information processing as well. The proposed taxonomies have classification parameters and parameter content. As parameter content has no lower-level classification, the table format is simple to understand.

In some specific cases, table format taxonomy presentation is used to provide a matrix of two properties (dimensions), where the category values and classes are presented in the intersection of the properties. An example of matrix format is the taxonomy used in Singh et al. [8], the Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) model. In this taxonomy, BYOD attacks are described and summarized in a matrix, where all BYOD attacks are placed in the intersection of attack type (passive, active and privacy attacks) and components (user, software, network, physical and web). Not all intersections are filled. However, the matrix representation allows the elimination of duplicate values in different categories.

Another solution to eliminate the duplication of values in various categories is the usage of the graph structure. Graph structure for taxonomy presentation is used by Chanti and Chithralekha [9] in the taxonomy of anti-phishing solutions. Graph structure allows the authors to define which solutions of content-based phishing solutions are associated with rule-based solutions.

In most cases, taxonomies are presented as a tree structure, where each branch defines classification criteria and child nodes indicate the values or classes. Each node is divided into sub-categories by defining the level of categorization. Hussain et al. [10] detail the spam review detection techniques in 2–4 level tree depth. Meanwhile, Gupta et al. [11] present multiple taxonomies related to phishing attacks. The level of depth of the taxonomies ranges from one level only to 1–3 level tree depth.

Combinations of multiple taxonomy formats exist. Liu and Lang [12] presented taxonomy for the intrusion detection systems. The taxonomy has a tree structure with references to map some criteria values in different branches of the tree. This solution is similar to the graph structure. However, they are visually oriented to a more common tree view but with the integration of different node notation (borders and colors) and additional lines. Another example of multiple presentation usage in taxonomy is presented by Disha et al. [13]. In this paper, phishing and anti-phishing taxonomies are presented as text descriptions. However, some specific parts of the taxonomies are detailed with smaller tree structure taxonomies and lists.

The analysis of the taxonomy representation forms illustrates that there is no single format for phishing attack taxonomy. However, the tree-based structure is the most popular for more complex taxonomies.

2.2. The Content of E-mail Phishing Attack-Related Taxonomies

The variety of taxonomies for e-mail phishing attacks is very limited. While the importance of social engineering in phishing attacks is undeniable, and e-mail messages are the most common form of it, most taxonomies are more abstract, and not enough attention is dedicated to e-mail phishing attacks particularly in them. For example, in the taxonomy of cyber threats against target applications [14], phishing attacks are mentioned only in a description of a social engineering attack. Phishing and particularly e-mail phishing attacks are not presented in this taxonomy. In the taxonomy of social engineering attacks for handheld devices [15], phishing attacks are included as a subcategory of social engineering; however, no details of the phishing attack are presented.

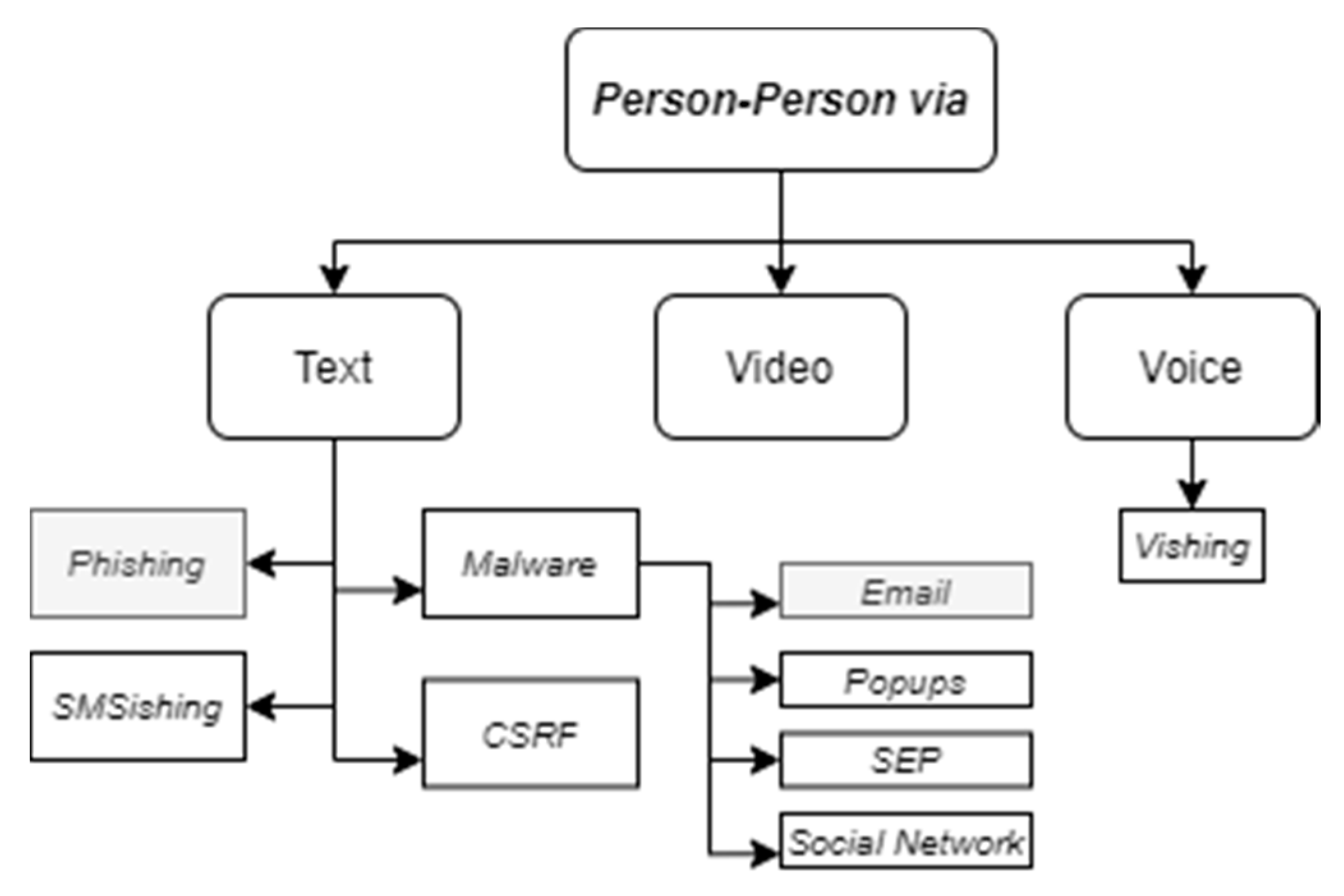

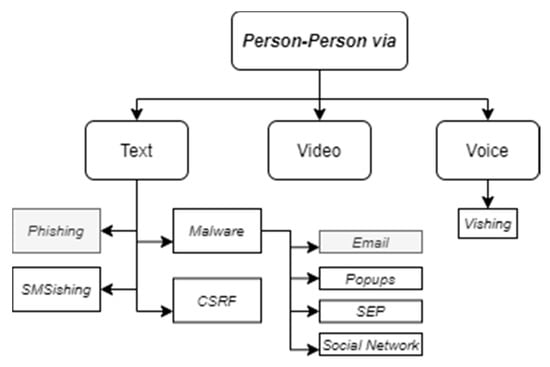

These two taxonomies are focused on a wider topic then just phishing attacks; however, even some social engineering attack taxonomies do not specify different characteristics of an e-mail phishing attack. For example, Krombholz et al. [16] define the taxonomy of phishing attacks where e-mail is mentioned as one of channels for social engineering close to instant messaging, telephone, VoIP, social network, cloud, website and physical. The authors define two more dimensions for social engineering attack classification: type (socio-technical, technical, physical, social) and operator (human, software). Other authors (Ivaturi and Janczewski [17]) present a more hierarchical tree structure with four levels. However, e-mail phishing attack-related nodes are very abstract and include phishing attack in person-to-person attacks via text category and malware distribution via e-mail in person-to-person via text category (see Figure 1). With some interpretations, the person-to-person category can be applied to e-mail phishing as well; however, it is not enough to present the full view of the possible e-mail phishing attack.

Figure 1.

Social engineering attack taxonomy. Reproduced from Figure 2 in [17].

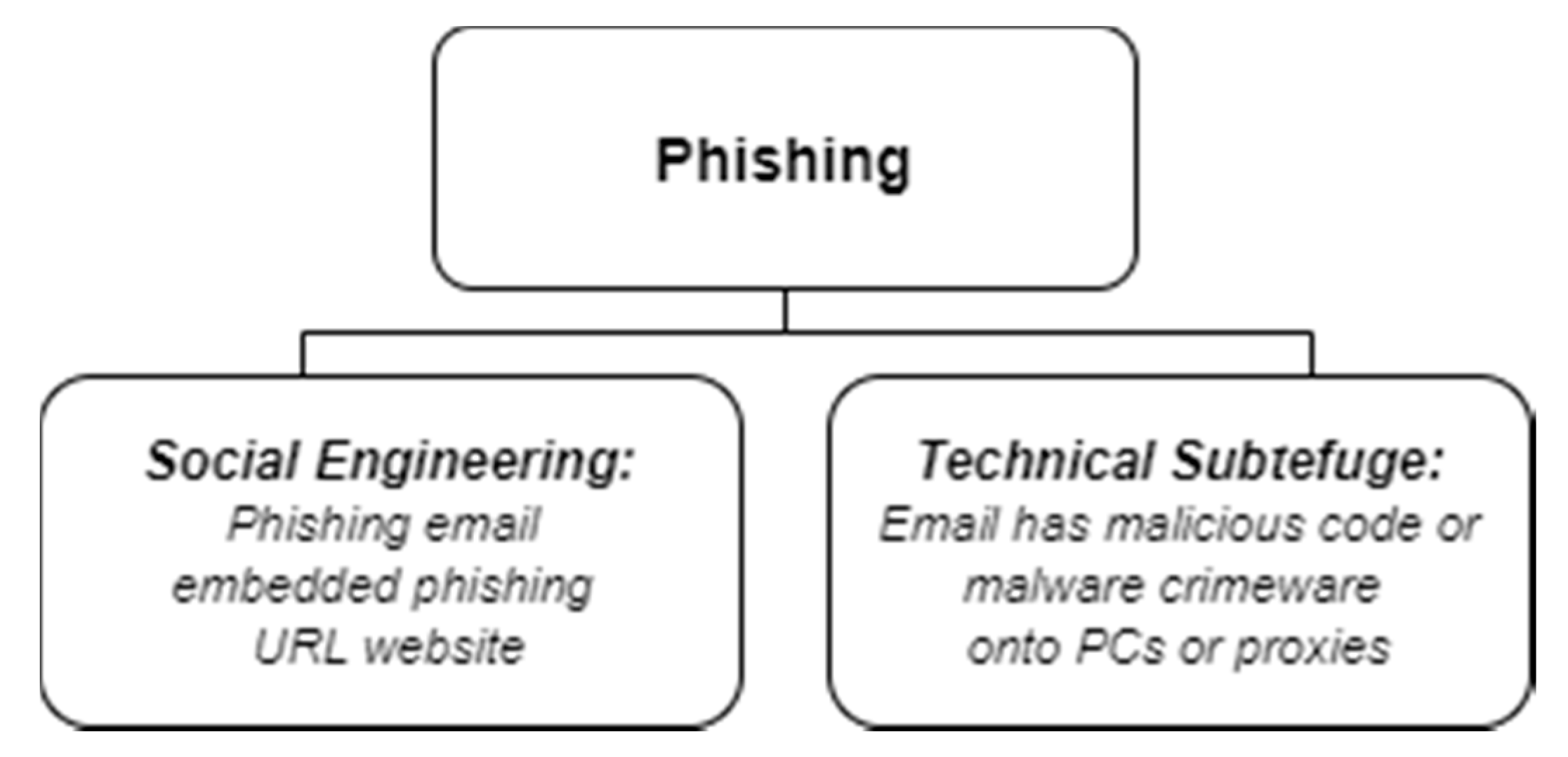

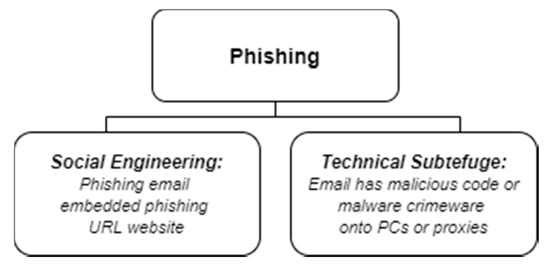

Analyzing phishing attack taxonomies, Daniel Pienta, Jason Bennett Thatcher and Allen C. Johnston [18] propose a phishing attack taxonomy; however, only five categories are distinguished (pharming, phishing, spear phishing, clone phishing and whaling) and are defined based on different attack characteristics. This taxonomy does not pay attention to e-mail phishing attack specifics and does not mention the environment. Meanwhile, Gupta et al. [19] present a phishing attack taxonomy where all categories are associated with e-mail phishing attacks. However, these e-mail phishing attacks are detailed by default into two categories only—spear-phishing and whaling. This is by far not enough to represent the full landscape of e-mail-based phishing attacks. Somewhat of a more detailed phishing attack taxonomy is proposed by Almomani et al. [20]. In this phishing attack taxonomy, proposed by the authors, phishing attacks are divided into social engineering and technical subterfuge. In most cases, phishing is treated as a subset of social engineering. In this taxonomy, infected e-mails that come with malicious code or malware highlighted are therefore categorized as social engineering with phishing e-mails. Embedded phishing and URL websites are indicated as a subset of phishing attacks (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phishing attack taxonomy. Reproduced from Figure 1 in [20].

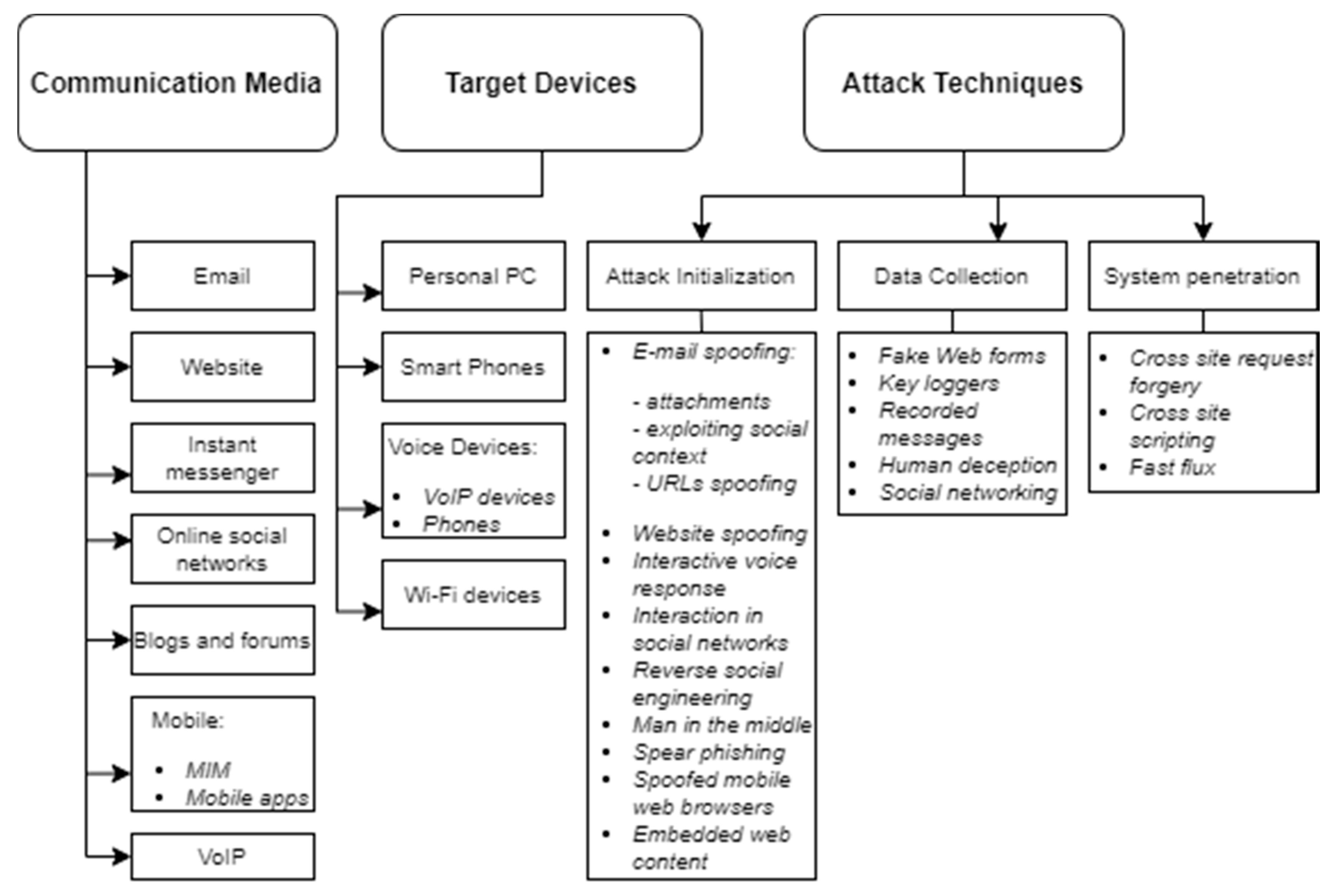

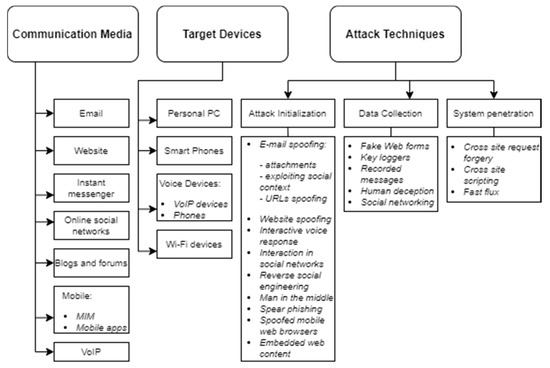

The most detailed phishing attack taxonomy is proposed by Aleroud and Zhou [21] (see Figure 3). The taxonomy classifies phishing attacks based on the communication media, target devices, attack techniques and possible countermeasures against phishing attacks.

Figure 3.

Phishing attack taxonomy. Reproduced from Figure 2 in [21].

Despite the fact that the taxonomy of Aleroud and Zhou [19] has a high number of lowest-level nodes, the relation between those nodes is not set. For example, in the attack techniques, the attack initialization phase interaction in social networks is listed. This type of attack is executed in attacks executed via online social networks and is loosely related to other communication media. This kind of link is missing for the correct perception of possible phishing attacks.

During the analysis of scientific papers, no taxonomies dedicated to e-mail-based phishing attacks were indicated. E-mail-based phishing attacks are defined in some social engineering and phishing attack taxonomies; however, no deeper analysis is available.

An example of a very detailed taxonomy is the framework for a taxonomy of fraud [22]. This framework is dedicated to financial fraud labelling. It has a combination of five-level classification and additional tags in several fields. While e-mail-based phishing attacks are used as a method for financial fraud, this framework is not fully adequate for e-mail phishing attack taxonomy. Therefore, to provide a clear classification for e-mail phishing attacks, a new taxonomy has to be developed.

3. The Proposed E-mail-Based Phishing Attack Taxonomy

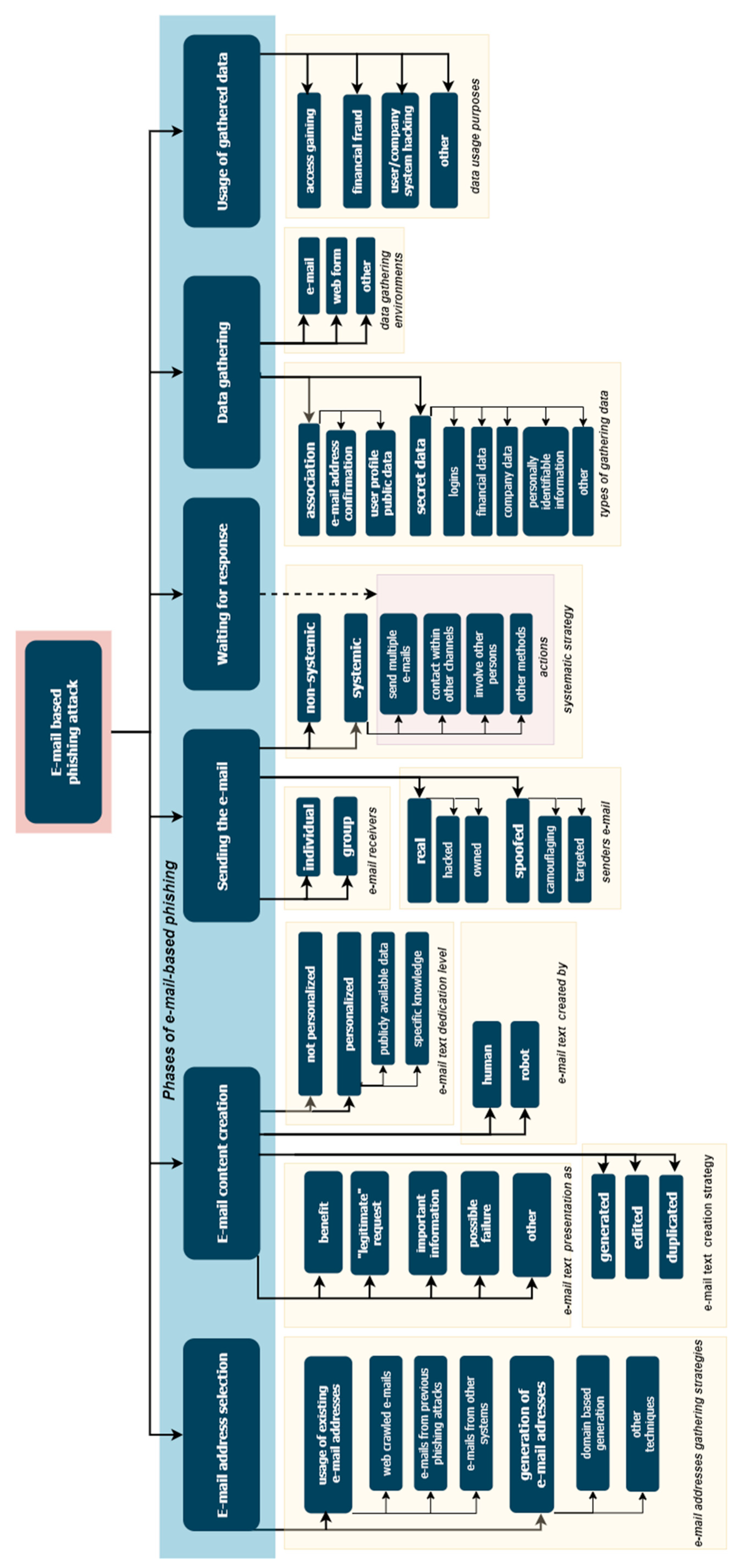

One of the main features defining the e-mail-based social engineering attacks is the phase of the phishing attack. We define six phases of the e-mail-based phishing attack:

- E-mail address selection. To execute an e-mail-based phishing attack, an e-mail address or addresses of the potential victim have to be obtained. In this phase, different strategies for e-mail address selection are used; therefore, we divide the address selection phase into strategy types for e-mail address selection (two main classes with subclasses in each of them).

- E-mail content creation. The content and text of the e-mail for the phishing attack has to be prepared to involve the victim in the phishing attack. This phase is very important and can be classified based on multiple criteria. We define four criteria for e-mail content creation for a phishing attack: idea for victim involvement in the phishing attack; e-mail text generation strategy; e-mail text creator type; e-mail text personalization level. Each of these criteria can obtain classes.

- Sending the e-mail to recipients. The method of how the attacker sends the e-mail to possible phishing victims is an important factor. The selected phishing attack strategy is implemented by sending the phishing e-mails; therefore, we detail the e-mail sending phase based on three criteria: sender’s e-mail address usage; the number of recipients in the phishing attack; usage of systemic phishing attack strategy. Possible classes for each of the criteria are provided in the taxonomy.

- Waiting for the response from the e-mail recipients. In most cases, the attacker just waits for the victim to respond to the phishing e-mail. However, in the case of a systematic strategy of a phishing attack, some additional actions can be executed while waiting for the victim’s response. The possible categories of attacker’s actions while they wait for the victim to respond is a part of e-mail sending systematic strategy; therefore, the classes are shared between those two phases.

- Phishing attack results and data gathering. The main purpose of a phishing attack is to get some specific data from the victim. We recommend defining the phase of gathered data based on the data gathering environment as well as types of gathered data. Possible classes for these criteria are listed in the taxonomy.

- Usage of gathered results and data. While the usage of gathered data is a little bit out of the scope of this work, it is very closely related to gathered data; therefore, we highlight the phase of gathered data usage and list possible purposes the attacker might have by using the phishing-attack-gathered data.

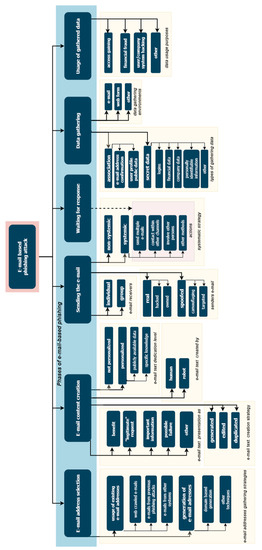

The overall view of the proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy is presented in Figure 4. All categorization criteria and possible classes for e-mail-based phishing attacks are listed and detailed below.

Figure 4.

Structure of the presented e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy.

- E-mail address selection strategies can be put into two main categories: usage of existing e-mail addresses and generation of e-mail addresses.

- ○

- The usage of existing e-mail addresses includes: web crawled e-mail addresses (obtained from listed e-mails in different web pages); e-mail addresses, gathered from previously executed phishing attacks (gathering of an e-mail address for phishing attack can be as a purpose of another phishing attack); e-mail addresses gathered from other systems or sources (some specific sources can be used to get an e-mail address for the prepared phishing attack).

- ○

- Generation of e-mail addresses is used as an alternative to the gathering of e-mail addresses if the selection of victims’ e-mail addresses is impossible. The most frequent case involves the generation of the most common e-mail addresses for a specific e-mail domain name (for example admin@domainname, sales@domainname, info@domainname, etc.). However, other different techniques to generate a possible e-mail address (a person’s credentials within different e-mail domain names, random sequences, etc.) are used too.

- Ideas for victim involvement in the phishing attack is the main element of any social engineering attack. We define the main factors that make the victim believe it is a legitimate request and requested data have to be provided:

- ○

- Benefit proposal motivates the victim to provide requested data to get some financial or another benefit from it. However, in most cases, the promised benefit is not provided, while the gathered data are used for different purposes.

- ○

- Impression of legitimate request does not involve additional questions requesting legitimacy, and the victim automatically sends the requested data. However, it is very difficult to generate such an e-mail text that provides a sufficient amount of detail about request management processes and internal data.

- ○

- Impression of an important event. The information request leads to stress for the victim; therefore, some victims do not analyze the e-mail with sufficient attention and proceed with a hurry to execute the requested actions, providing the requested data.

- ○

- Impression of a possible failure in the case of the data not being provided. This is a very similar strategy to the previous one as it activates the same emotions for the victim. At the same time, it is more focused on understanding the internal processes, as the attacker must know or imagine what kind of processes might be associated with failure if information is not provided by the victim.

- ○

- Other strategies are possible too. The phishing attack is much harder to identify if it uses some very specific weaknesses of the victim, as the traditional phishing attack e-mail texts are well known and are easy to recognize as a phishing attack.

- E-mail text generation strategy. In this strategy, the source defines how the e-mail text is generated. There are three main strategies:

- ○

- Generated—a new, case-specific phishing attack text. It might be time-consuming; however, is harder to identify it as a phishing attack by signature-based e-mail filtering systems.

- ○

- Edited—the e-mail text is copied from another e-mail (legitimate or phishing attack e-mail), and some parts of the e-mail are changed (replacing the name of the recipient, etc.).

- ○

- Duplicated—the e-mail text is copied from other sources and is not changed at all.

- E-mail text can be created manually or by using automated solutions; therefore, we define two types of e-mail text creators:

- ○

- Human—e-mail text is written or changed by the person.

- ○

- A bot or computer—e-mail text is generated or modified by a computer program or bot.

- E-mail text personalization level is closely related to the e-mail text generation strategy, and we define two types of personalization:

- ○

- Not personalized—the e-mail text is very abstract, and no personal information is added in the e-mail.

- ○

- Personalized—the e-mail text includes some personalized information about the recipient or the e-mail. The emails can be personalized by using publicly available data (such as recipient’s name, surname, the title of the organization, etc.) or by using some specific knowledge (data about recent user’s visits, financial operations, etc.). In other sources, the use of personalized phishing attacks with publicly available victim data is called spear phishing, while personalized phishing attacks that use some specific knowledge and are usually directed to some higher position persons are classed as whaling attacks.

- The sender’s e-mail address is one of the main factors in identifying a phishing attack. The attacker can use his real or spoofed e-mail address:

- ○

- A real e-mail address uses no specific techniques to change itself. The attacker might use hacked e-mail account or register and create an untraceable e-mail account for phishing e-mail distribution.

- ○

- Spoofed e-mail addresses are changed to trick the victim by showing a specific e-mail address that is not possible to obtain legitimately. In some cases, the e-mail address is spoofed to mimic a specific, targeted e-mail address, while another type is e-mail address camouflage, where the aim is to generate a very similar e-mail address to a legitimate one, but no identical match is needed.

- The number of recipients in the phishing attack can be used for phishing attack identification and should be associated with the number of recipients only (not based on the text of the e-mail):

- ○

- Individual—the e-mail recipient is one address. Multiple e-mails are sent at the same time, but it is classed as individual if the victim can see his or her own e-mail address as the recipient.

- ○

- Group—the e-mail recipients are multiple e-mail addresses. The usage of multiple addresses might be an additional method to illustrate that the sender knows multiple, related e-mails in the organization or multiple e-mails of the same person or to stimulate concurrency between several victims to obtain trust before somebody else does.

- Usage of a systematic phishing attack strategy allows higher phishing attack success probability; however, it requires additional actions and knowledge about the victim:

- ○

- Non-systematic strategy requires no additional actions and usually involves sending one phishing attack e-mail and then waiting for the results.

- ○

- Systematic phishing attacks require additional actions and knowledge. The simplest case is the sending of multiple e-mails to the same victim by remembering or adding some additional information in the later e-mails. Another solution is to contact the victim through other channels (phone call, social networks, etc.). Other communication channels are used to remind the recipient about the e-mail or to motivate them to act and convince them of the legitimacy of the request. The motivation and convincing can be achieved by involving other persons too (contacting different persons individually and motivating them to collaborate or exchange information between them). There may be other specific cases (related to information publishing in the media, etc.) where some additional attacker actions are executed to implement attack strategy.

- Data gathering environment defines how the attacker gets the information and what kind of environment is used for it:

- ○

- An e-mail reply is one of the main victim actions, as it requires no additional investment for data gathering tools—the user replies to the received e-mail by providing requested data.

- ○

- Webforms are very popular too. The attacker creates a web page with a data input functionality. Some web sites are unique, while others mimic or spoof other systems and trick the user into thinking they are using a legitimate web site while submitting the data to the attacker.

- ○

- Other types of data gathering during phishing attacks are used too. Attackers can use social networks, phones, etc.

- Types of gathered data vary in different phishing attacks. We define the gathered information using two types:

- ○

- Association—data needed to generate the victim’s profile from publicly available data; however, because of the large quantity of related data, the data have to be associated, to ensure the integrity of the user profile. In some cases, the existence of such an e-mail is enough from the victim; in other cases, some publicly available personal data are gathered from the victim’s response.

- ○

- Secret data are more valuable in a phishing attack, but at the same time are harder to get from the victim. The phishing-attack-targeted secret data might include user credentials, the victim’s financial data, enterprise-related secrets, personally identifiable information (date of birth, social security number, etc.) or others.

- The purpose of phishing attack data usage is closely related to the type of gathered data during the phishing attack. The main categories are:

- ○

- Gaining access to a specific system. If login data are gathered during a phishing attack, the same logins might apply to gain access to this or even other systems of the same victim.

- ○

- Financial fraud is related to the victim’s financial and personal data. In some cases, the phishing attack leads to victim actions where the victim transfers their money to the attacker as a result of their belief that they are executing a legitimate money transfer to a different source.

- ○

- User/company system hacking is related to gaining access, but sometimes the phishing attack is oriented towards collecting specific data on enterprise management structure, used technologies, etc.

- ○

- Other types of purposes of the phishing attack exist; however, they are not as common and vary a lot; therefore, the other class was added to include all of them.

The proposed taxonomy is oriented towards e-mail-based phishing attacks, but at the same time, some phases (data gathering and gathered data usage) are adapted to any phishing attack as well.

4. Validation of the Proposed E-mail-based Phishing Attack Taxonomy

In most cases, the taxonomy quality depends on two factors: how detailed it is and how adaptable it is. Therefore, we investigated how our proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy performs both in content compared to other similar taxonomies as well as how its usage changes the phishing attack notation.

4.1. Proposed E-mail-Based Phishing Attack Taxonomy Comparison with Existing Taxonomies

To compare our proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy with other similar taxonomies, scientific papers and conference proceedings were analyzed. Publications were from the last 15 years in Clarivate Analytics Web of Science, Google Scholar and other scientific databases. From the gathered material only 27 papers were related to classification, taxonomy of phishing, social engineering attacks or their mitigation and solutions. Only 11 of these papers mention phishing e-mails, and only six of them were suitable for taxonomy comparison (papers on phishing countermeasures were eliminated).

For comparison, we listed our proposed criteria and classes (only first level, without deeper classification) of e-mail-based phishing attacks and evaluated whether these criteria/classes are presented in the analyzed taxonomy (scientific paper). The results of the comparison are presented in Table 1. The sign “+” in the class row means the class is included in the analyzed taxonomy or is mentioned in the description, while the sign “-” means there is no mention of this class in the taxonomy. If several rows are merged, the sign “+” means the criterion is presented in the analyzed taxonomy and has all classes in it, while the sign “-” in the merged rows means the criteria is not mentioned in the analyzed taxonomy at all.

Table 1.

Proposed taxonomy content comparison to other related taxonomies.

The comparison with existing taxonomies shows that none of the analyzed taxonomies define phishing attack actions while waiting for the victims’ response. In most cases, a phishing attack is understood as a non-systematic attack, with no combined actions to support the main phishing e-mail, while in real life strategies, systematic phishing attacks appear and include the usage of different media, the involvement of additional persons, etc.

As none of the analyzed taxonomies provide data on systemic phishing attacks, additional actions of the same phishing attack could not be assigned as the same phishing attack and were treated as another one. This is not suitable or convenient for cybercrime investigators as without a link to or understanding of related actions, the full investigation is not possible.

Another difference compared to the existing phishing attack taxonomies is that we detail six phases of the e-mail-based phishing attack, while the phases of e-mail address selection, content creation and gathered data usage are ignored by most of the other taxonomies (just one or two taxonomies detail these phases). Existing taxonomies do not dedicate enough attention to how the attacker prepares for the attack. Without e-mail addresses, the selection phase of cybercrime investigation would not be able to identify the first actions by trying randomly selected and non-existent victim addresses (incident-notating persons would get the information from e-mail system logs). As well as gathered data usage, information would be useful for cybercrime investigators,; therefore, it is useful to add in the taxonomy. In our proposed taxonomy’s content creation phase we present personalized and not personalized e-mail content and divide personalized content into the personalized class when publicly available data are used and when the additional, secret information is used in the e-mail message. Such a description is simpler compared to spear-phishing and whaling attack titles; therefore, the taxonomy could be more intuitive to non-expert security personnel.

The most common criterion to define a phishing attack is the environment for data gathering, where a phishing attack is associated with the spoofed web page and data submission in a web-based form. This criterion and the class are mentioned in all analyzed taxonomies, and in most cases, they do not present all possible environments to obtain a user’s secret data. It is also worth mentioning that the gathered data are usually presented as secret data, and there are no details on what kinds of data are gathered during the phishing attack. Existing taxonomies do not mention phishing attacks where the attacker collects the initial data by linking the user profile and e-mail.

The inability of the reviewed taxonomies to cover the full view of the e-mail-based phishing attack phases, classification criteria and classes are highlighted by analyzing criteria and class coverage percentages. The Phishing and Anti-Phishing taxonomy [13] covered (defined similar criteria or presented classes and mentioned cases which are part of the criteria) 69% of our proposed criteria, while all the rest of the taxonomies did not reach 50% of coverage. In regard to covered classes, the maximum coverage was 38% by the same Phishing and Anti-Phishing taxonomy [13], while the taxonomies of Almomani et al. [20] and Krombholz et al. [16] covered only 13% of our detailed first-level classes (deeper classification was not analyzed).

4.2. Phishing Attack Notating by Using Proposed E-mail-based Phishing Attack Taxonomy

To evaluate the practical application of the proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy, we compared how detailed phishing attack notations were before the taxonomy and how the phishing attack descriptions changed after adapting the proposed taxonomy.

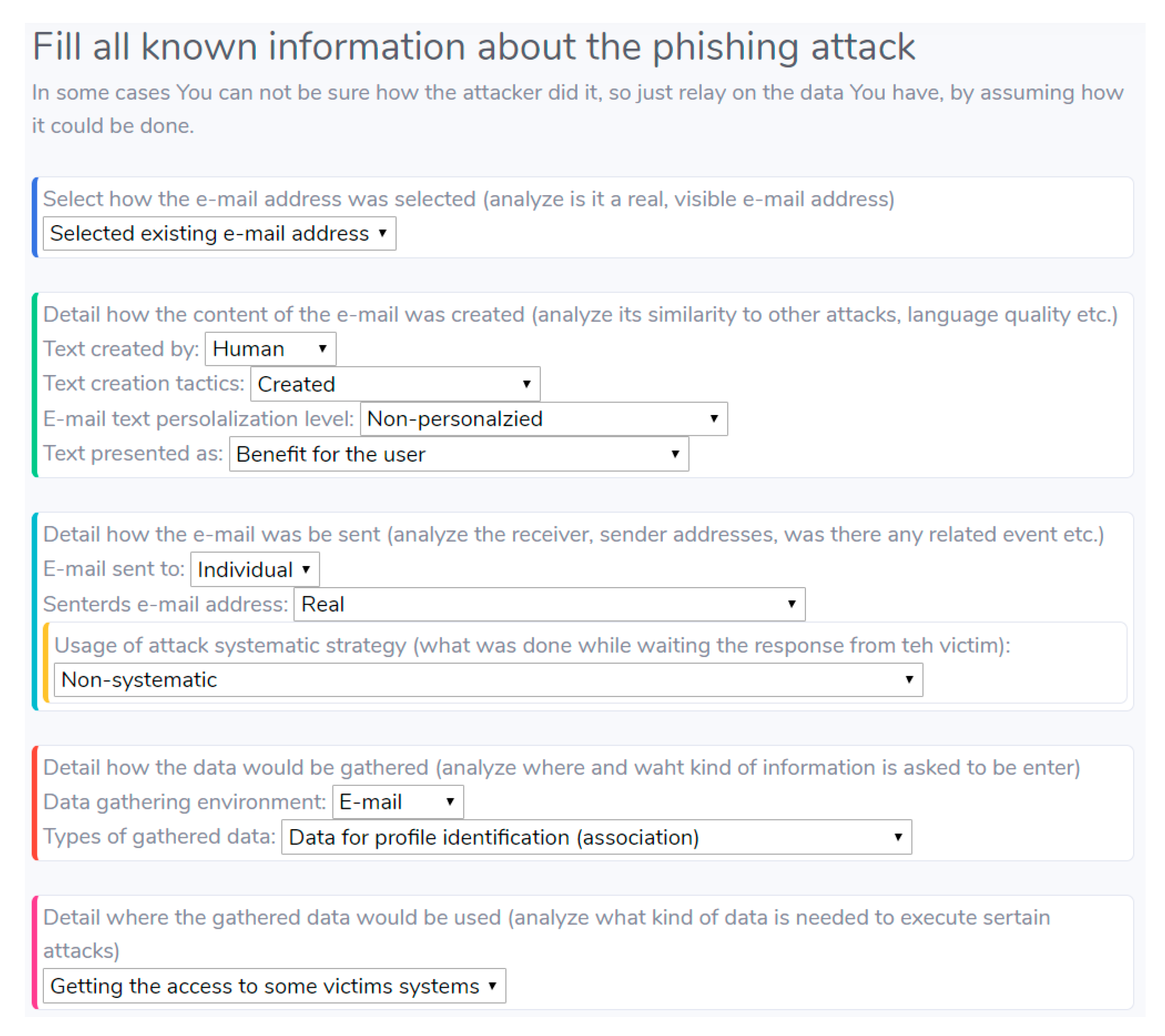

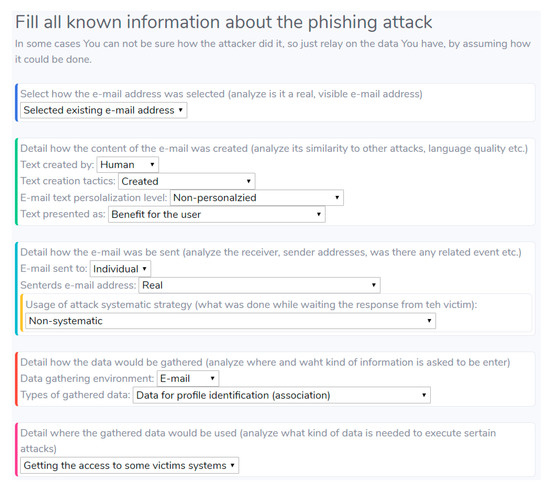

Vilnius Gediminas Technical University has an Information Technology Management Department (ITMD). One of the responsibilities of this department is to investigate cyber-attacks against VGTU and its employees. Information about e-mail-based phishing attacks is gathered from the e-mail system (filtering out undesired e-mails) and emails received from employees in the HelpDesk system. Each incident is categorized and detailed, notated by systemically presenting the known information about the attack. E-mail-based phishing attacks are notated manually by the employees of ITMD. Several persons do the notation, as there are several phases (initial notation, detail confirmation, modification after incident investigation) with different notators and multiple persons can be used in each of the phases. After proposing the e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy, a form to notate e-mail-based phishing attacks (see Figure 5) is presented and used as a template for incident notating.

Figure 5.

Form for e-mail-based phishing attack notating.

For comparison purposes, to define how the usage of the proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy changes the notation of phishing attacks, we took the last 50 phishing attacks, which were notated in a free form and asked to do the notation once again but by using the provided notation form (based on the proposed taxonomy). The attacks were the same, and the persons who notated them were the same (the same employees were used in this process, but a specific incident can be notated by different persons). Therefore, we were able to compare how the notations differed depending on the notation form.

Among those 50 phishing attack e-mails, all of them were collected by ITMD (registered by VGTU employees or obtained from system monitoring logs). About 74% of them were written in English, while 26% were written in (or translated into) Lithuanian. It is worth mentioning that one e-mail was generated by VGTU itself, as a testing tool to evaluate employees’ credulity to phishing attacks [23].

The benefit of used taxonomy for phishing e-mail notation can be evaluated by several criteria:

- Unambiguity of assigned description—whether the description is understandable and needs additional explanation to another person or even machine to understand the description. The unambiguity can be evaluated by measuring whether the description is clear or uses blurry expressions.

- The detail level in the description—whether the description reflects all properties of the phishing attack and there is no need to analyze the e-mail again. The detail level can be evaluated by measuring how many different properties or categories are assigned to the phishing attack.

In our experiment, the first evaluation criterion (unambiguity) is clearly expressed as free form notating and has no dictionary or clear requirements, while taxonomy-based phishing e-mail notation allows selection of possible properties from a discrete list. As the free form description is not standardized, sometimes the same person notates two identical phishing e-mail by using different text (“won a lottery” and “fake information about possible profit”). With taxonomy-based notation, the same keywords are selected, and the variety of similar e-mails are noted by missing some values because of the inability to identify them.

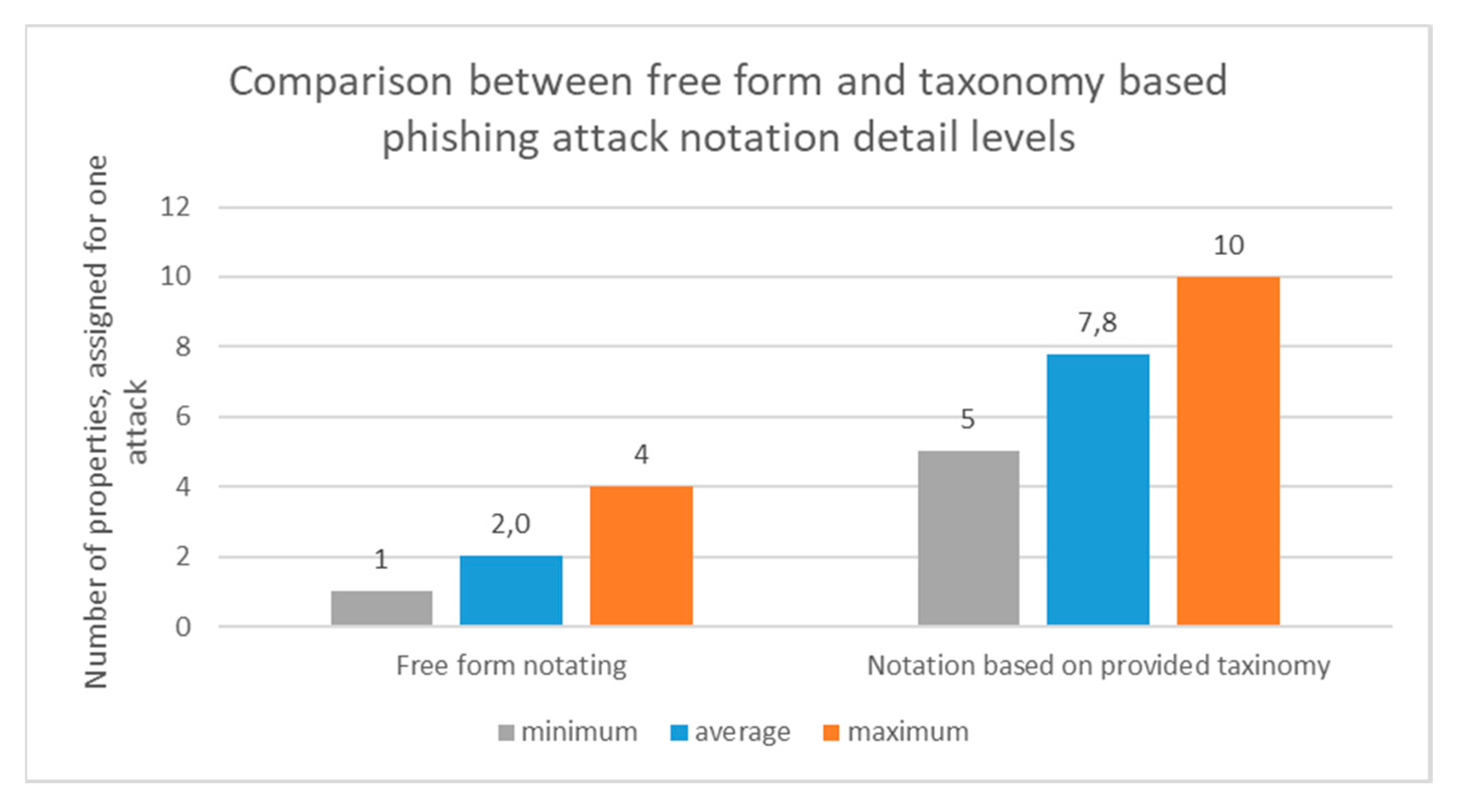

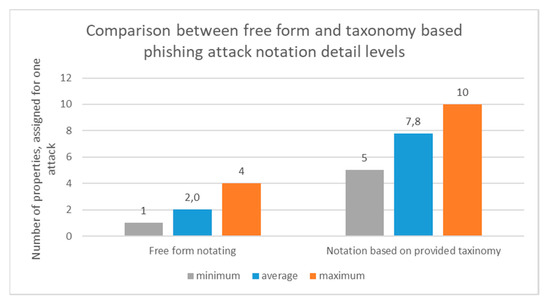

The results of the detail level comparison between the notation using a free form and proposed taxonomy-based phishing attack notation form are presented in Figure 6. The free form notation was very short and mentioned just the main properties such as “fake request to change password”, “won a lottery”, “need help to spend money”, “attached file”, “fake website for password change”, etc. Meanwhile, by using the notation form based on the proposed taxonomy, the minimum number of assigned classes (employee selected something other than “unknown”) for one phishing attack is five. This is more properties per one attack than the maximum number of properties among all free form notation records. On average, 7.8 classes were assigned for one phishing attack by using a proposed notation form. The higher numbers in the taxonomy-based phishing e-mail notating show that the notating person can identify more properties of the phishing attack by providing more information about the attack. Therefore, the investigator of the phishing attack gets more data to assign priorities, a responsible person or even to investigate the attack.

Figure 6.

Comparison of phishing attack notation levels in free form and taxonomy-based phishing attack form.

As the notating results might not be normally distributed, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to test the hypothesis for whether any differences between the two methods (free form and taxonomy-based notating) are due to chance (essentially based on the median of the differences). For the two-tailed hypothesis, the sample size is 50, the significance level is 0.05 and the value of W is calculated to be equal to 0. This means the distribution is approximately normal; therefore, we used the value of z, which is equal to -6.154. As the p-value is < 0.00001, the result is significant at p < 0.05. Based on this non-parametric statistical hypothesis test, we can confirm that the proposed taxonomy-based phishing attack e-mail notation produces a significantly different and larger number of notated properties compared to the free form notating process. More detailed, unified and unambiguous descriptions of e-mail-based phishing attacks allow easier analysis of notated attacks—a company can generate different phishing attack incident reports that are presented in different views and grouped by different classes, etc.

5. Conclusions

This review of existing phishing attack taxonomies highlights the lack of e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomies. Existing phishing attack taxonomies focus on highlighting the difference between social engineering and technical aspects of phishing attacks; therefore, they do not pay sufficient attention to the e-mail-based phishing attack specifics and more sophisticated, systematic strategy-based phishing attacks.

A proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy is presented as a tree structure, where first-level branches define the phases of an e-mail-based phishing attack. In the second level of the taxonomy, each phase has at least one criterion to detail the phishing attack, while classes for each criterion have one or two-level structures. Such a structure is intuitive, while text descriptions of each phase, criterion and class allow for its unambiguous understanding.

The proposed e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy has a wider range of classification criteria compared to the existing phishing attack taxonomies, while the number of classes (first level, not including the subclasses) is more than two times larger than any existing phishing attack taxonomy. The higher number of phases, criteria and classes in the proposed taxonomy allows for more specific notation of existing e-mail-based phishing attacks. Therefore, the number of assigned classes for one phishing attack incident increased on average from two to eight properties.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to taxonomy design, analysis of existing e-mail-based phishing attack taxonomies, experiment planning and execution, data analysis and writing the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cybersecurity Threatscape: Q3 2019. Available online: https://www.ptsecurity.com/ww-en/analytics/cybersecurity-threatscape-2019-q3/?sphrase_id=70070 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Salahdine, F.; Kaabouch, N. Social engineering attacks: A survey. Future Internet 2019, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garshol, L.M. Metadata? Thesauri? Taxonomies? Topic maps! Making sense of it all. J. Inf. Sci. 2004, 30, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medelyan, O.; Witten, I.H.; Divoli, A.; Broekstra, J. Automatic construction of lexicons, taxonomies, ontologies, and other knowledge structures. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2013, 3, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah-Boateng, E.O.; Amanor, P.M. Phishing, SMiShing & Vishing: An assessment of threats against mobile devices. J. Emerg. Trends Comput. Inf. Sci. 2014, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Grégio, A.R.A.; Afonso, V.M.; Filho, D.S.F.; Geus, P.L.D.; Jino, M. Toward a taxonomy of malware behaviors. Comput. J. 2015, 58, 2758–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloslavskaya, N.; Tolstoy, A.; Zapechnikov, S. Taxonomy for unsecure digital information processing. In Proceedings of the 2016 Third International Conference on Digital Information Processing, Data Mining, and Wireless Communications (DIPDMWC), Moscow, Russia, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.M.; Siang, S.S.; San, O.Y.; Hashimah, N.; Malim, A.H.; Shariff, A.R.M. Security attacks taxonomy on bring your own devices (BYOD) model. Int. J. Mob. Netw. Commun. Telemat. (IJMNCT) 2014, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanti, S.; Chithralekha, T. Classification of Anti-phishing Solutions. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Turab Mirza, H.; Rasool, G.; Hussain, I.; Kaleem, M. Spam Review Detection Techniques: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Tewari, A.; Jain, A.K.; Agrawal, D.P. Fighting against phishing attacks: State of the art and future challenges. Neural Comput. Appl. 2017, 28, 3629–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lang, B. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods for Intrusion Detection Systems: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disha, D.N.; Rachana, N.B.; Kumari Deepika, N.S.G. Phishing & Anti-Phishing: A Review. Int. J. Eng. Tech. Res. (IJETR) 2014, 2, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Narwal, B.; Mohapatra, A.K.; Usmani, K.A. Towards a taxonomy of cyber threats against target applications. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2019, 22, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Foozy, F.; Ahmad, R.; Abdollah, M.F.; Yusof, R.; Mas’ud, M.Z. Generic Taxonomy of Social Engineering Attack and Defence Mechanism for Handheld Computer Study. J. ICACT 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krombholz, K.; Hobel, H.; Huber, M.; Weippl, E. Advanced social engineering attacks. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2015, 22, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaturi, K.; Janczewski, L. A taxonomy for social engineering attacks. In International Conference on Information Resources Management; Centre for Information Technology, Organizations, and People; Association for Information Systems, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pienta, D.; Thatcher, J.B.; Johnston, A.C. Taxonomy of Phishing: Attack Types Spanning Economic, Temporal, Breadth, and Target Boundaries. In Proceedings of the 13th Pre-ICIS Workshop on Information Security and Privacy, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13 December 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, B.B.; Arachchilage, N.A.; Psannis, K.E. Defending against phishing attacks: Taxonomy of methods, current issues and future directions. Telecommun. Syst. 2018, 67, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, A.; Gupta, B.B.; Atawneh, S.; Meulenberg, A.; Almomani, E. A survey of phishing e-mail filtering techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 15, 2070–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleroud, A.; Zhou, L. Phishing environments, techniques, and countermeasures: A survey. Comput. Secur. 2017, 68, 160–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, M.; DeLiema, M.; Deevy, M. Framework for a Taxonomy of Fraud; Stanford Longevity Center/FINRA Financial Investor Education Foundation/Fraud Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 25, p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rastenis, J.; Ramanauskaitė, S.; Janulevičius, J.; Čenys, A. Credulity to Phishing Attacks: A Real-World Study of Personnel with Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2019 Open Conference of Electrical, Electronic and Information Sciences (eStream), Vilnius, Lithuania, 25 April 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).