The Presence of Periodontitis in Patients with Von Willebrand Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

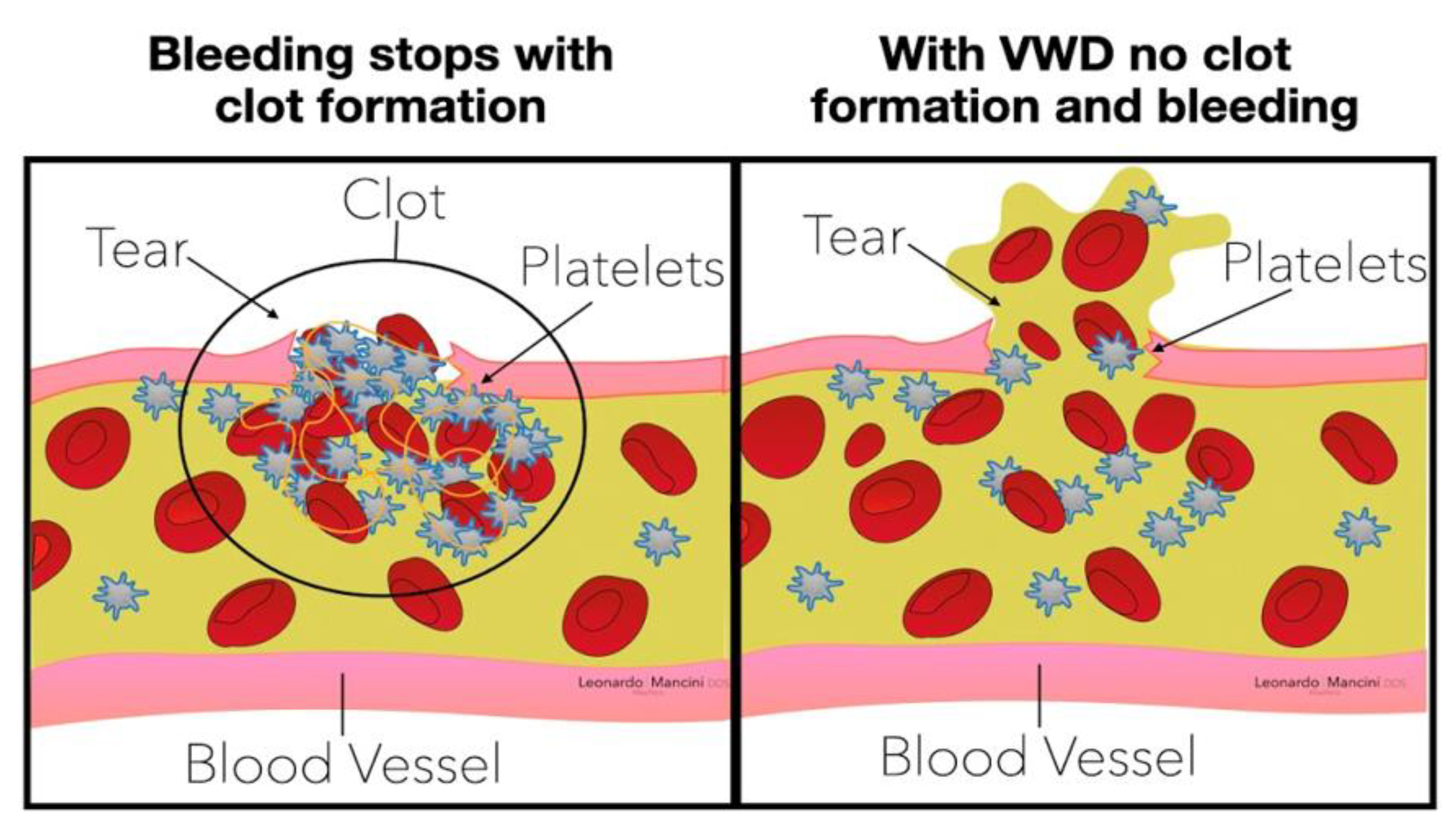

:1. Introduction

- Type 1.

- A quantitative deficiency of VWF, the most common autosomal dominant form.

- Type 2.

- A qualitative alteration of VWF synthesis, which can result from various genetic abnormalities with autosomal dominant inheritance.

- Type 3.

- A rare autosomal recessive disease in which homozygotes have no detectable von Willebrand factor activity.

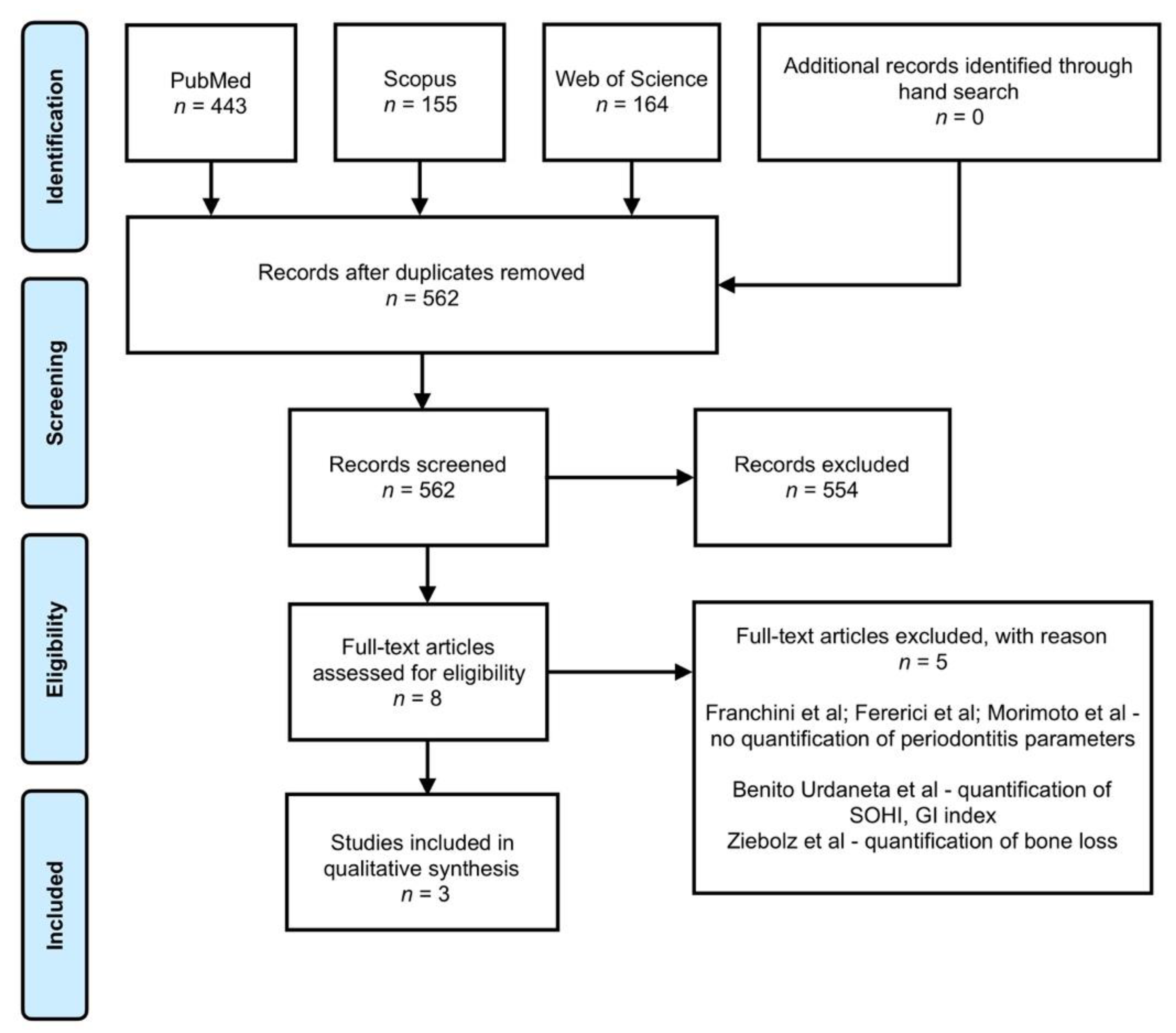

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria (PECO Framework)

- (a)

- Population, adult patients >18 years;

- (b)

- Exposure, patients with VWD;

- (c)

- Comparison, patients without VWD;

- (d)

- Outcome, Primary periodontal parameters (probing pocket depth (PPD), bleeding on probing (BOP), gingival bleeding index (GBI), and periodontal inflamed surface area (PISA)).

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- (a)

- Animal in vitro studies; not clinical trial, cross-sectional, or cohort studies; reviews; case reports; letters to the editor;

- (b)

- Missing data regarding periodontal parameters (PPD, BOP, GBI, and PISA) and Von Willebrand parameters (von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen and VWF activity);

- (c)

- Predictive and prognostic studies;

- (d)

- Insufficient data that could not be used for the meta-analysis;

- (e)

- Studies published in other languages than English.

2.3. Information Source and Search Process

2.4. Data Extraction

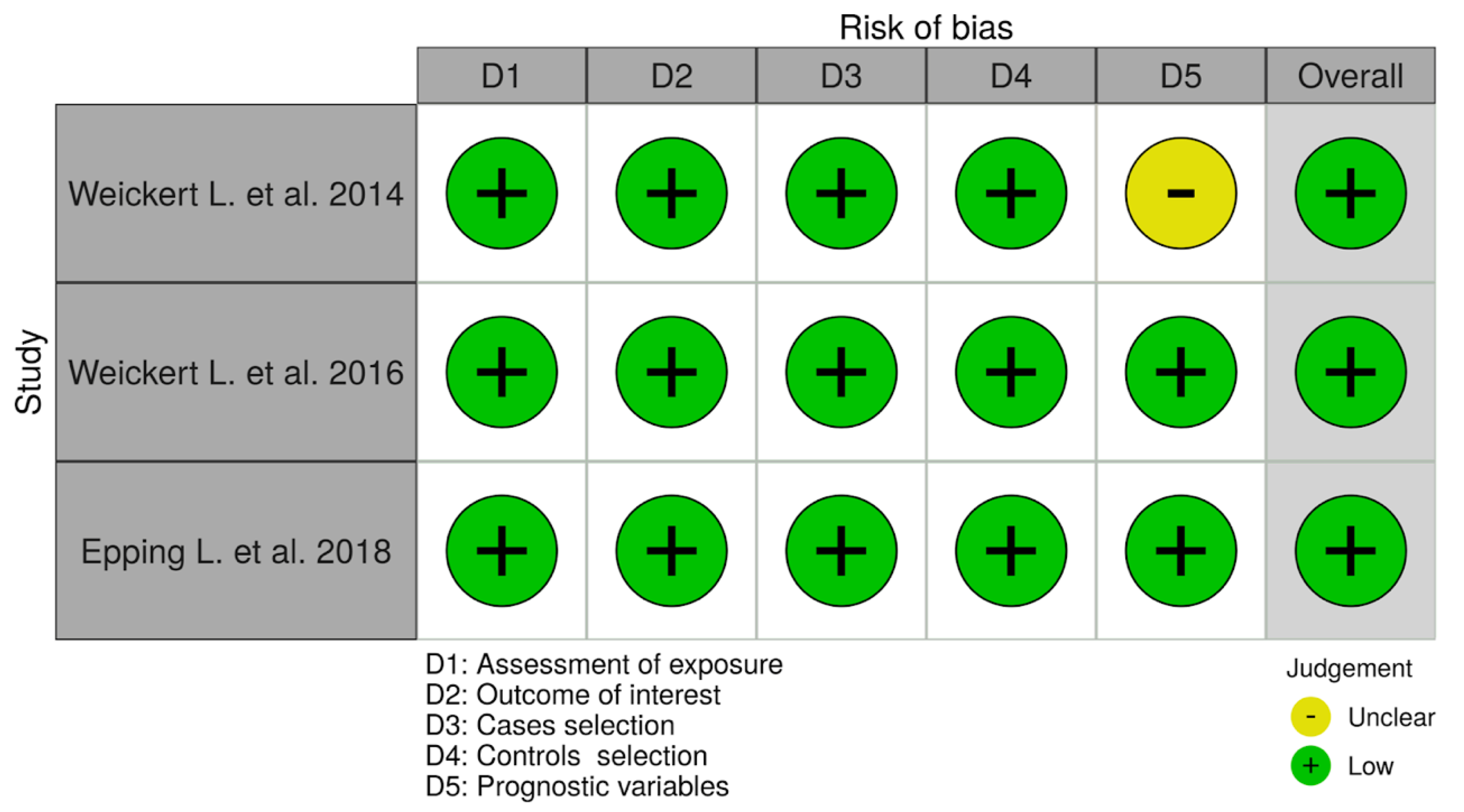

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

- (a)

- Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

- (b)

- Can we be confident that cases had developed the outcome of interest and controls had not?

- (c)

- Were the cases (those who were exposed and developed the outcome of interest) properly selected?

- (d)

- Were the controls (those who were exposed and did not develop the outcome of interest) properly selected?

- (e)

- Were cases and controls matched according to important prognostic variables or was statistical did adjustment carry out for those variables?

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias for Individual Studies

3.4. Qualitative Synthesis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Data and Statistics on Oral Health. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/oral-health/data-and-statistics (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Nazir, M.A. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, N.P.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontal health. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. S1), S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fogarty, H.; Doherty, D.; O’Donnell, J.S. New developments in von Willebrand disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalot, M.A.; Al-Khatib, M.; Connell, N.T.; Flood, V.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; James, P.; Mustafa, R.A. An international survey to inform priorities for new guidelines on von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia 2020, 26, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metjian, A.D.; Wang, C.; Sood, S.L.; Cuker, A.; Peterson, S.M.; Soucie, J.M.; Konkle, B.A. Bleeding symptoms and laboratory correlation in patients with severe von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia 2009, 15, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghaie, H.; Forrest, B.; Shukla, K.; Liu, T. Dental extraction in a patient with undiagnosed Von Willebrand’s Disease: A case report. Aust. Dent. J. 2021, 66, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouides, P.A.; Phatak, P.D.; Burkart, P.; Braggins, C.; Cox, C.; Bernstein, Z.; Belling, L.; Holmberg, P.; MacLaughlin, W.; Howard, F. Gynaecological and obstetrical morbidity in women with type I von Willebrand disease: Results of a patient survey. Haemophilia 2000, 6, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, M. Gastrointestinal bleeding in von Willebrand disease. Thromb. Res. 2006, 118, S13–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaie, P.; Shaygan Majd, H.; Ziaee, M.; Sharifzadeh, G.; Osmani, F. Evaluation of gum health status in hemophilia patients in Birjand (a case-control study). Am. J. Blood Res. 2020, 10, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ibsen Olga, P.J. Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienis, 6th ed.; Saunders Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781455748266. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A.M.; Brewer, A.; Creagh, D.; Hook, S.; Mainwaring, J.; McKernan, A.; Yee, T.T.; Yeung, C.A. Guidance on the dental management of patients with haemophilia and congenital bleeding disorders. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 215, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shastry, S.P.; Kaul, R.; Baroudi, K.; Umar, D. Hemophilia A: Dental considerations and management. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2014, 4, S147–S152. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benford, D.; Halldorsson, T.; Jeger, M.J.; Knutsen, H.K.; More, S.; Naegeli, H.; Noteborn, H.; Ockleford, C.; Ricci, A.; Rychen, G.; et al. The principles and methods behind EFSA’s Guidance on Uncertainty Analysis in Scientific Assessment. EFSA J. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2018, 16, e05122. [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel, P.T. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weickert, L.; Miesbach, W.; Alesci, S.R.; Eickholz, P.; Nickles, K. Is gingival bleeding a symptom of patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease? A case-control study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickert, L.; Krekeler, S.; Nickles, K.; Eickholz, P.; Seifried, E.; Miesbach, W. Gingival bleeding and mild type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis Int. J. Haemost. Thromb. 2017, 28, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epping, L.; Miesbach, W.; Nickles, K.; Eickholz, P. Is gingival bleeding a symptom of type 2 and 3 von Willebrand disease? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azhar, S.; Yazdanie, N.; Muhammad, N. Periodontal status and IOTN interventions among young hemophiliacs. Haemophilia 2006, 12, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Hussain, S.B.; Zehra, S.A.; Proença, L.; Orlandi, M.; Mendes, J.J.; D’Aiuto, F. Periodontitis and circulating blood cell profiles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Hematol. 2021, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, H.; Ainousa, A. Dental management of patients with inherited bleeding disorders: A multidisciplinary approach. Gen. Dent. 2017, 65, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, M.E.; Paulo, S. Guidelines for Dental Treatment of Patients with Inherited Bleeding Disorders; World Federation of Hemophilia: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vinckier, F.; Vermylen, J. Dental extractions in hemophilia: Reflections on 10 years’ experience. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985, 59, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Brewer, A.K.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; Key, N.S.; Kitchen, S.; Llinas, A.; Ludlam, C.A.; Mahlangu, J.N.; Mulder, K.; Poon, M.C.; et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia 2013, 19, e1–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author. Year. Country. Reference | Study Type | Participants | Characteristics of Participants | Hematology Analysis | Periodontal Disease Parameters | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weickert, 2014, Germany, [17] | Prospective case control | Control (n = 40) VWD Type 1 (n = 50) | Control: Female (n = 34) Male (n = 6) Gingivitis (n = 13) Periodontitis (n = 27) VWD: Female (n = 43) Male (n = 7) Gingivitis (n = 13) Periodontitis (n = 37) | VWF antigen Ristocetin cofactor Factor VIII | BOP GBI PPD PCR | BOP (VWD 14.5 ± 10.1%, control 12.3 ± 5.3%) GBI (VWD 10.5 ± 9.9%, control 8.8 ± 4.8%) PPD (VWD 1.8 ± 0.9 mm, control 1.9 ± 0.5 mm) PCR (VWD 53. ± 24.1%, control 49.5 ± 15.9%) VWF antigen (VWD 62.6 ± 15.4%, control 111.8 ± 27.4%) Ristocetin cofactor (VWD 47.2 ± 10.0%, control: 91.6 ± 26.0%) Factor VIII (VWD 84.6 ± 17.7%, control 108.6 ± 21.1%) | VWD is not associated with pronounced inflammatory response to oral biofilm (in terms of GBI, BOP). |

| Weickert, 2016, Germany, [18] | Case Control | Control (n = 40) VWD Type 1 (n = 50) | Control: Female (n = 34) Male (n = 6) Gingivitis (n = 13) Periodontitis (n = 27) VWD: Female (n = 43) Male (n = 7) Gingivitis (n = 13) Periodontitis (n = 37) | VWF antigen Ristocetin cofactor Factor VIII | BOP GBI | BOP (VWD 17.0 ± 7.2%, control 17.2 ± 7.6%) GBI (VWD 10.0 ± 5.0%, control 12.2 ± 5.5%) VWF antigen (VWD 62.6 ± 15.4%, control 111.8 ± 27.4%) Ristocetin cofactor (VWD 47.2 ± 10.0%, control 91.6 ± 26.0%) Factor VIII (VWD 84.6 ± 17.7%, control 108.6 ± 21.1%) | Gingival bleeding in VWD type 1 patients might be determined by gingival inflammation. |

| Epping, 2018, Germany [19] | Prospective case control | Control (n = 24) VWD Type 2, 3 (n = 24) | Control: Female (n = 17) Male (n = 7) Gingivitis (n = 11) Periodontitis (n = 13) VWD: Female (n = 17) Male (n = 7) Gingivitis (n = 11) Periodontitis (n = 13) | VWF antigen VWF activity Factor VIII | BOP GBI PPD PCR PISA | BOP (VWD 14.5 ± 10.1%, control 12.3 ± 5.3%) GBI (VWD 10.5 ± 9.9%, control: 8.8 ± 4.8%) PPD (VWD 1.8 ± 0.9 mm;,control 1.9 ± 0.5 mm) PCR (VWD 53. ± 24.1%, control 49.5 ± 15.9%) PISA (VWD 154.4 ± 124 mm2, control 136.1 ± 95.3 mm2) VWF antigen (VWD 44.0 ± 45.9%, control 122.1 ± 47.2%) VWF activity (VWD 24.7. ± 23.4%, control 122.1 ± 45.1%) Factor VIII (VWD 55.6. ± 46.3%, control 129.8 ± 27.5%) | VWD is not associated with a higher inflammatory response to the oral biofilm. In terms of BOP and GBI, this study failed to detect increased gingival bleeding in VWD patients. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mester, A.; Mancini, L.; Marchetti, E.; Baciut, M.; Bran, S.; Lucaciu, O.; Baciut, G.; Tomuleasa, C.; Pasca, S.; Piciu, A.; et al. The Presence of Periodontitis in Patients with Von Willebrand Disease: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146408

Mester A, Mancini L, Marchetti E, Baciut M, Bran S, Lucaciu O, Baciut G, Tomuleasa C, Pasca S, Piciu A, et al. The Presence of Periodontitis in Patients with Von Willebrand Disease: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(14):6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146408

Chicago/Turabian StyleMester, Alexandru, Leonardo Mancini, Enrico Marchetti, Mihaela Baciut, Simion Bran, Ondine Lucaciu, Grigore Baciut, Ciprian Tomuleasa, Sergiu Pasca, Andra Piciu, and et al. 2021. "The Presence of Periodontitis in Patients with Von Willebrand Disease: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 11, no. 14: 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146408

APA StyleMester, A., Mancini, L., Marchetti, E., Baciut, M., Bran, S., Lucaciu, O., Baciut, G., Tomuleasa, C., Pasca, S., Piciu, A., Voina-Tonea, A., Opris, H., Prodan, D. A., & Onisor, F. (2021). The Presence of Periodontitis in Patients with Von Willebrand Disease: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 11(14), 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146408