Lean Maturity Assessment in ETO Scenario

Abstract

:1. Introduction

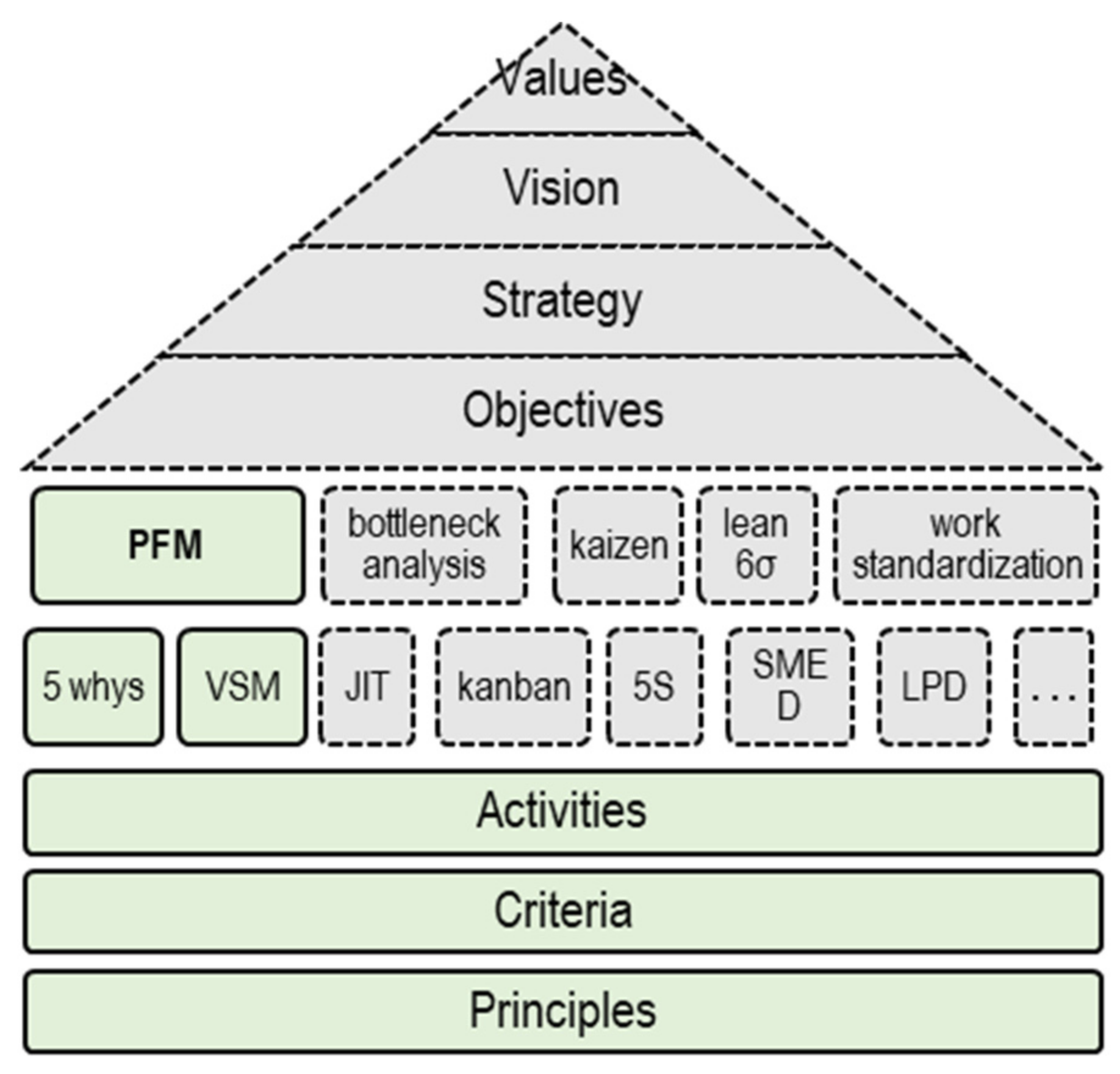

1.1. Lean Manufacturing

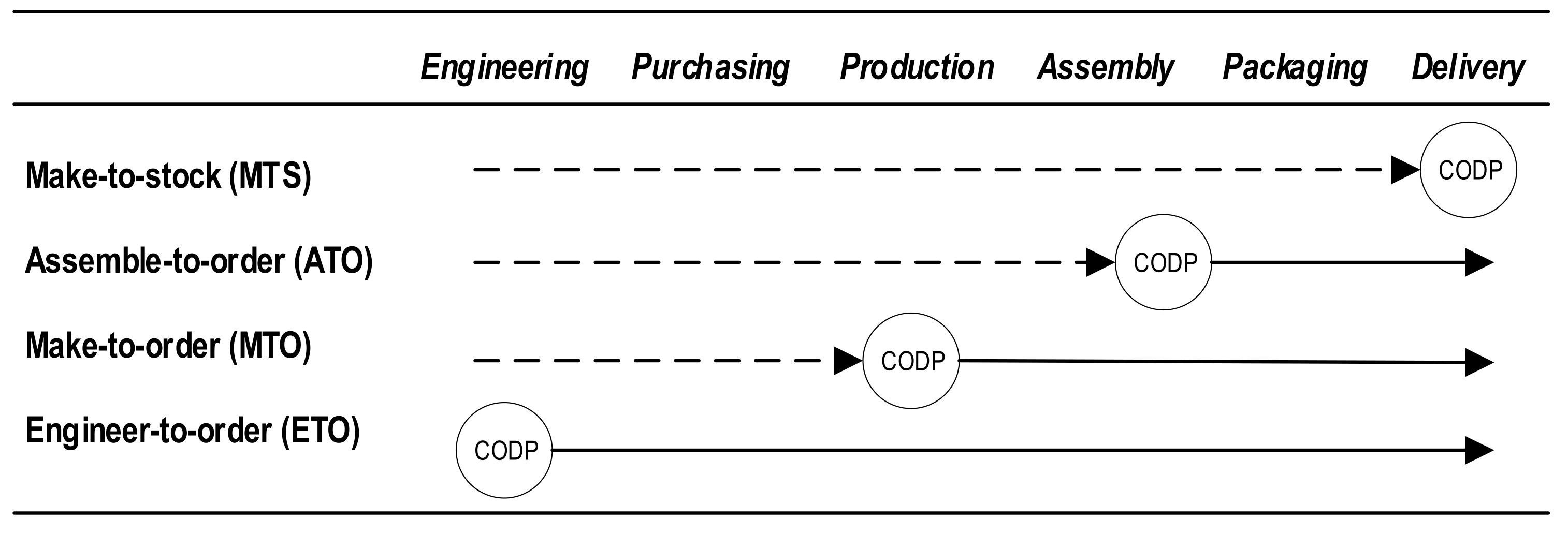

1.2. Engineer to Order (ETO)

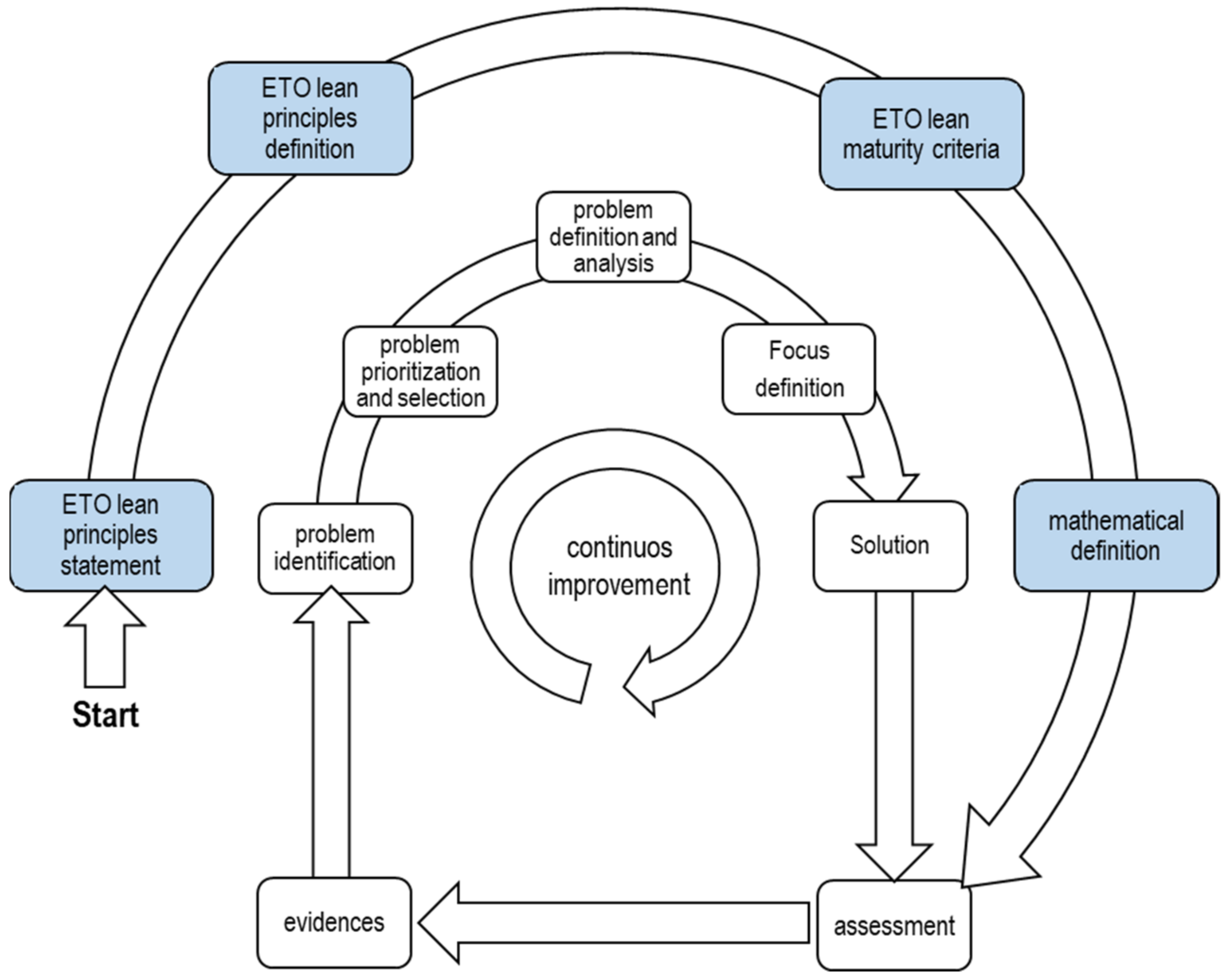

1.3. ETO Lean Assessment

2. Methodology

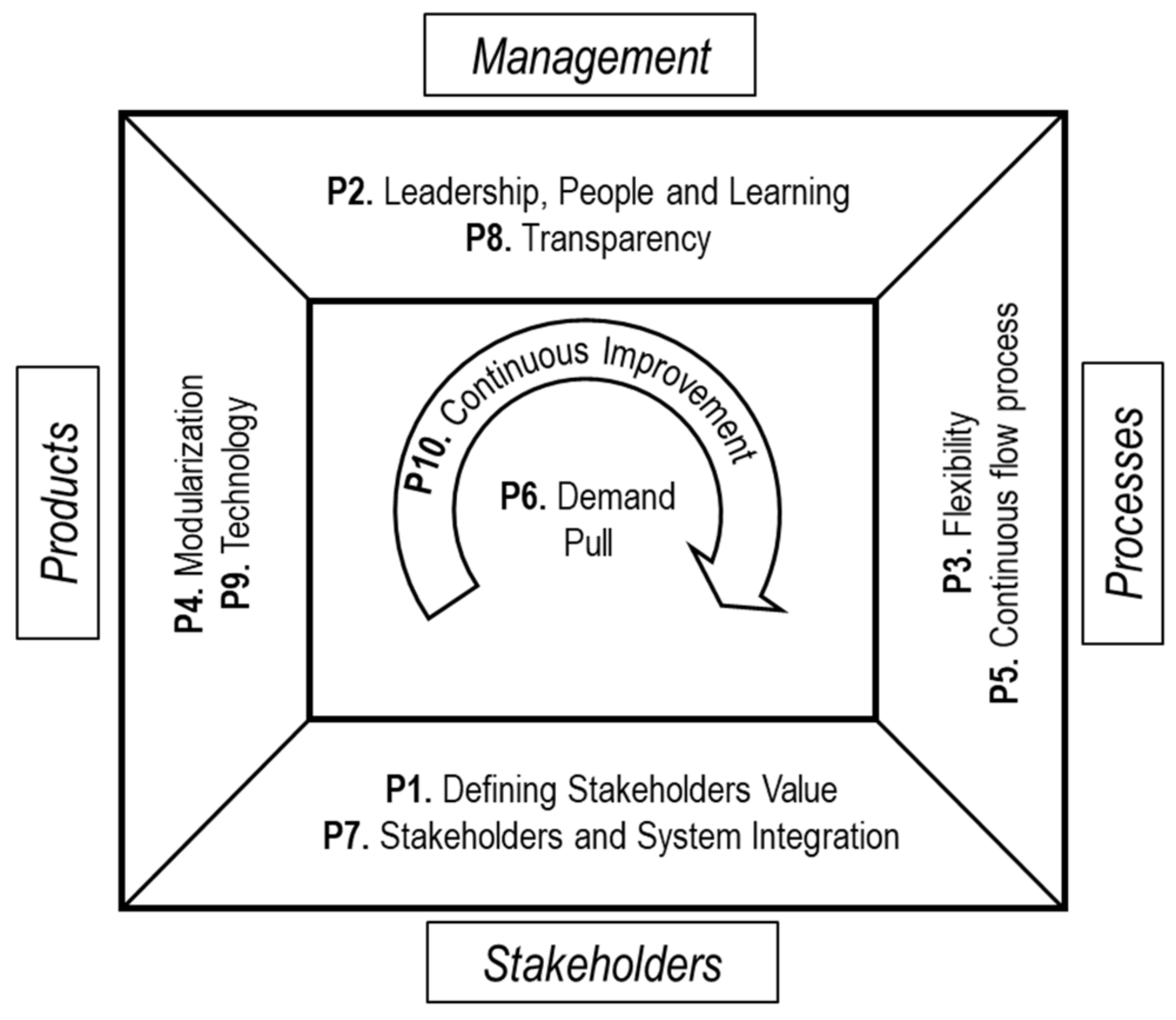

2.1. ETO Lean Principles Definition

2.1.1. P1. Defining Stakeholders Value

- Identification of relevant stakeholders, including external (e.g., customers) and internal (e.g., employees and company owners) stakeholders. The identification process may result in a long list.

- Identification and assignment of (key) performance attributes, called values, to the stakeholder group. In this step, the main values in which the stakeholders’ groups are interested are defined.

- Definition of value weights through the pairwise comparison model, stakeholders cluster method, or others. Weights for an attribute are determined simply, by comparing pairs of attributes one at a time.

- Computation of a total value index for each option being assessed by the analysis. A cumulative score for each option is calculated.

- Research an option that satisfies most of the main concerns of the stakeholders. Create of a new option, as well, possibly based on those originally considered.

2.1.2. P2. Leadership, People and Learning

- Transformation and change management,

- Product development, and

- Procedures for infrastructures.

2.1.3. P3. Flexibility

2.1.4. P4. Modularization

2.1.5. P5. Continuous Process Flow

2.1.6. P6. Demand Pull

2.1.7. P7. Stakeholders and Systems Integration

2.1.8. P8. Transparency

2.1.9. P9. Technology

2.1.10. P10. Continuous Improvement

2.2. ETO Lean Assessment Criteria

2.3. Alternative Mathematical Definition

2.3.1. P3. Flexibility

2.3.2. P4. Modularization

2.3.3. P5. Continuous Process Flow

2.3.4. P6. Demand Pull

3. Case Study

3.1. Tool Validation

3.1.1. P3. Flexibility

3.1.2. P4. Modularization

3.1.3. P5. Continuous Flow Process

3.1.4. P6. Demand Pull

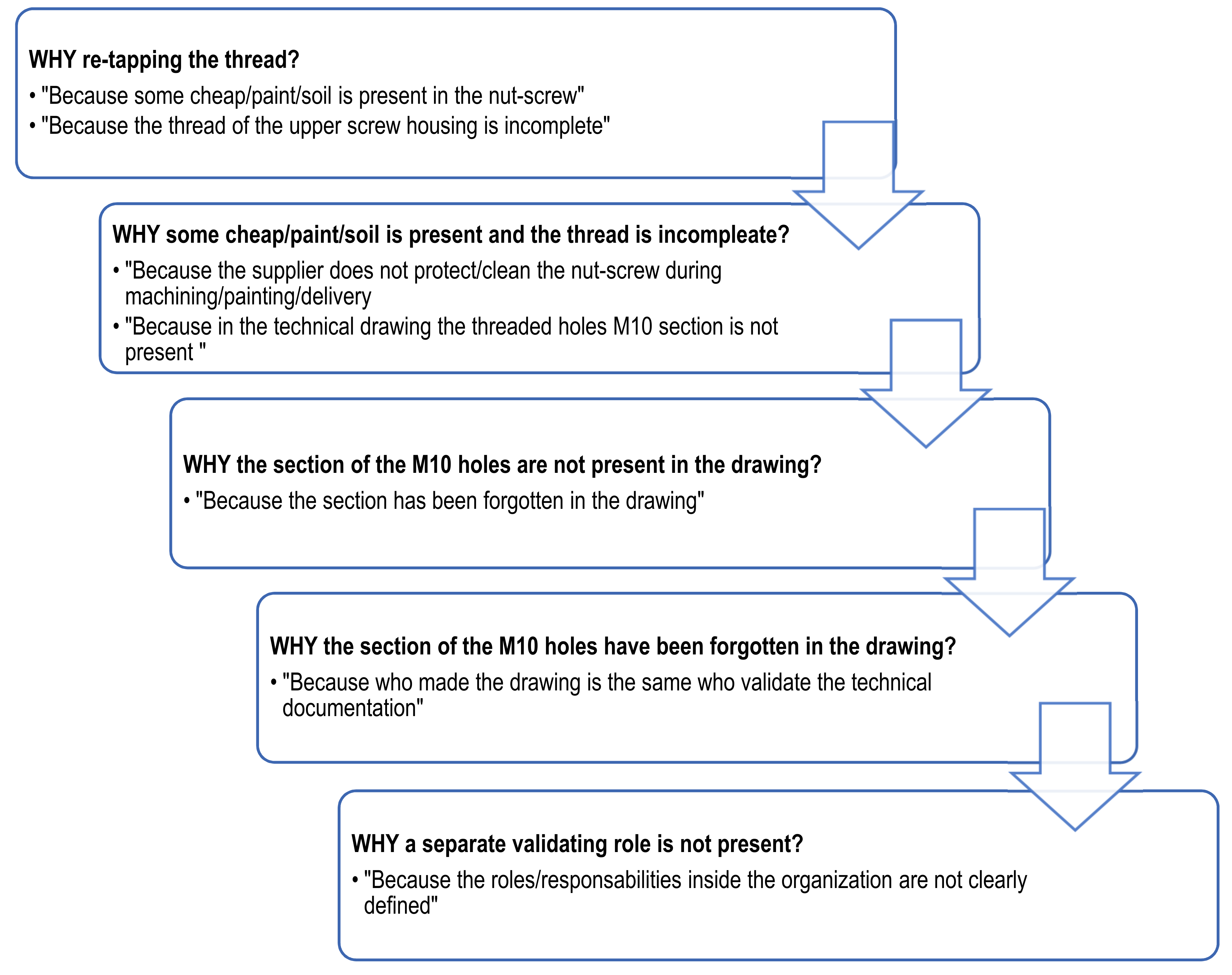

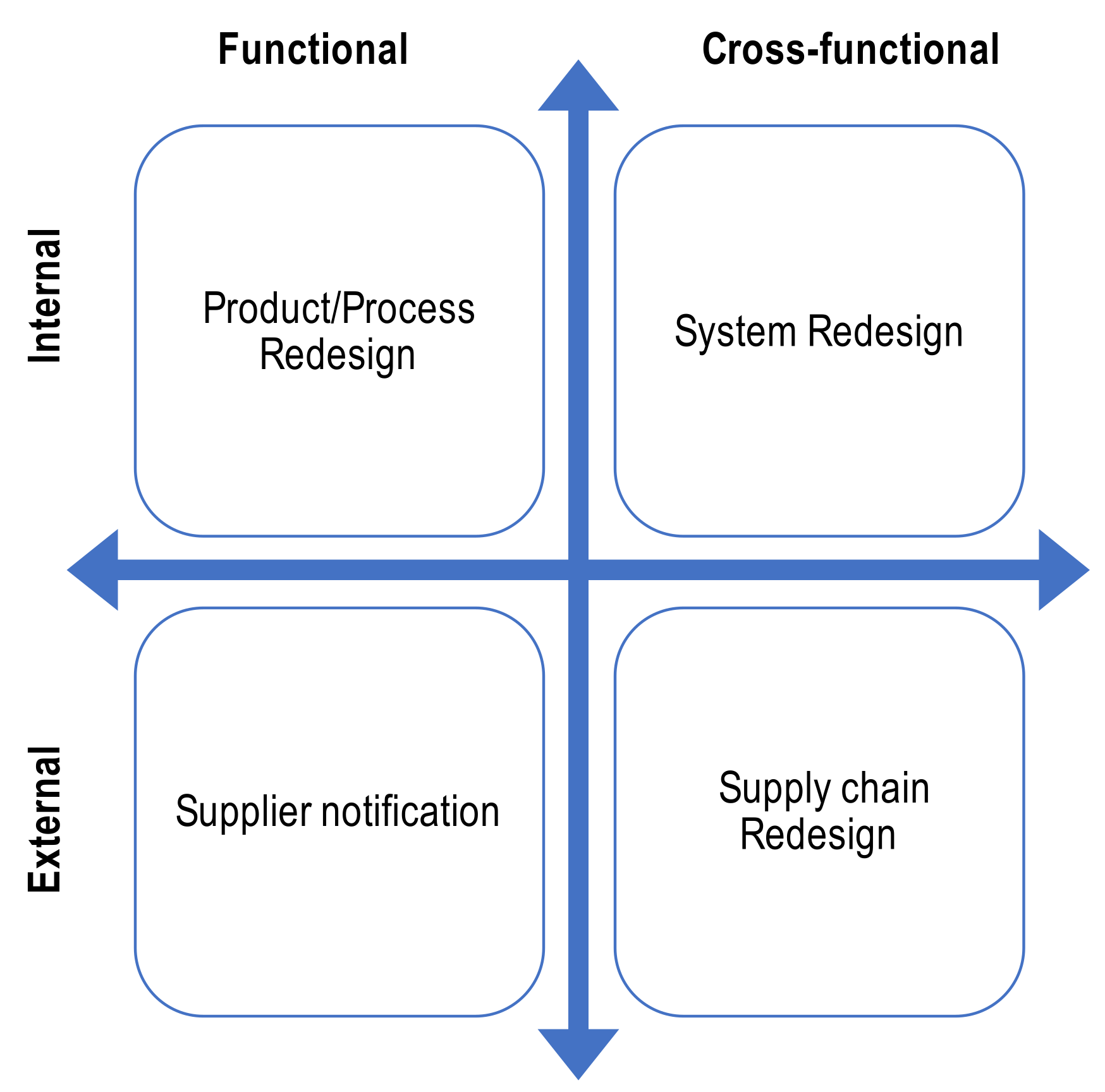

3.2. Problem Solving

3.2.1. Problem Identification

3.2.2. Problem Prioritization and Selection

3.2.3. Problem Definition

3.2.4. Problem Analysis

- (a)

- External: generated by the supplier (because the supplier does not protect/clean properly the nut-screw during manufacturing/painting/delivery).

- (b)

- Internal: generated by the technical office (because the section of the M10 holes is not present in the technical drawing).

3.2.5. Focus Definition

3.2.6. Solution Implementation

- (a)

- “The supplier does not properly protect/clean the nut-screw during manufacturing/painting/delivery”.Solution: in the case of an external and circumscribed problem like this, the resolution is a simple notification to the supplier to request a preventive action for the regenerating of that NC. Improved communication could help speed up this process.

- (b)

- “The section of the M10 holes is not present in the technical drawing”:Solution: Focusing on the internal cause, two actions were adopted: the correction of the technical drawing, and the removal of the root cause—the absence of defined roles/responsibilities. The responsible-accountable-consultant-informed (RACI) tool was a simple and effective way to avoid the repetition of similar issues caused by the absence of formal separation of duties inside the company.

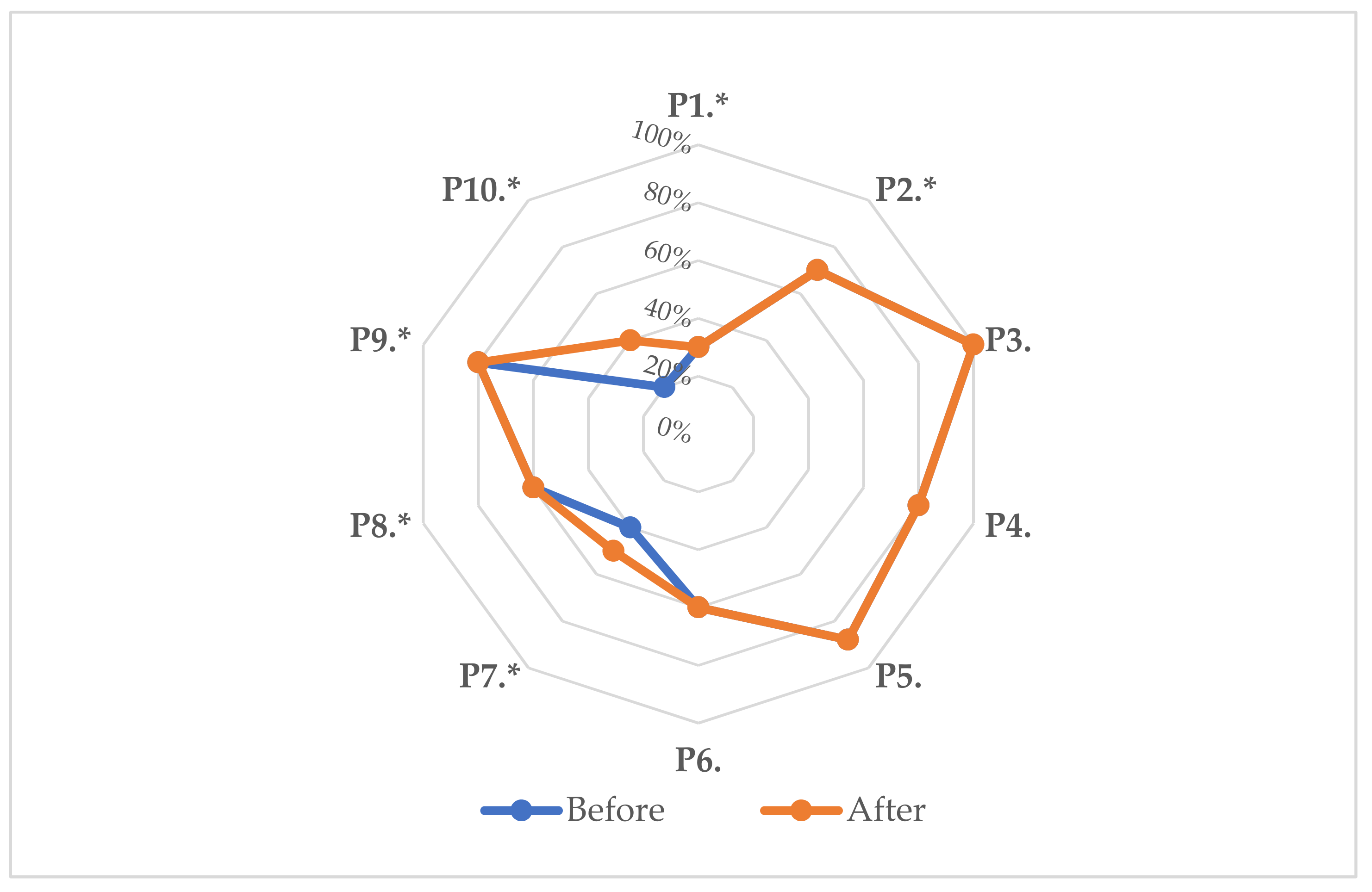

4. Results

5. Discussion

- -

- In (a), it facilitated collaboration within the company throughout the value chain.

- -

- The use of the responsible-accountable-consultant-informed (RACI) tool in (b) defined roles and responsibilities within the organization matrix by focusing on the interested parties within the organization.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T.; Roos, D. The Machine That Changed the World; Free Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; Volume 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamu, J.; Sangwan, K.S. Lean Manufacturing: Literature Review and Research Issues. In International Journal of Operations and Production Management; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 876–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production-Taiichi Ohno. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?hl=it&lr=&id=7_-67SshOy8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&ots=YpRxz9wcDZ&sig=UIHS3U_qLIireW7mspYhdunOJ2w&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Basu, R. Six Sigma to Fit Sigma. IIE Solut. 2001, 33, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgaard, J.J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M. Lean Production, Six Sigma Quality, TQM and Company Culture. TQM Mag. 2006, 18, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, R.; Balaji, A.N.; Satheesh Kumar, R.M. A Review on Lean Manufacturing Implementation Techniques. In Procedia Engineering; Elsevier Ltd: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 97, pp. 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sugimori, Y.; Kusunoki, K.; Cho, F.; Uchikawa, S. Toyota Production System and Kanban System Materialization of Just-in-Time and Respect-for-Human System. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1977, 15, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yazdani, B. Toyota Production System: An Integrated Approach to Just-in-Time; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perico, P.; Arica, E.; Powell, D.J.; Gaiardelli, P. MES as an Enabler of Lean Manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaki, K. New Manufacturing Challenge: Techniques for Continuous Improvement. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?hl=it&lr=&id=6EHtJE8NHD0C&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&ots=BMlbLEXGjX&sig=a-iDbwTHa5JFKRHhku40ABGBc0s&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Acero, R.; Torralba, M.; Pérez-Moya, R.; Pozo, J.A. Value Stream Analysis in Military Logistics: The Improvement in Order Processing Procedure. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar Sharma, R.; Gopal Sharma, R. Integrating Six Sigma culture and TPM framework to improve manufacturing performance in SMEs. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2014, 30, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumapayi, O.M.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Mwema, F.M.; Ogbonna, O.S. Six Sigma versus Lean Manufacturing—An Overview. In Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier Ltd: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 26, pp. 3275–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, H.S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B.J. A Conceptual Examination of Lean, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma Models for Managing Waste in Manufacturing SMEs. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 17, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.; Ferreira, L.P.; Fernandes, N.O.; Sá, J.C.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Silva, F.J.G. Improving the Machining Process of the Metalworking Industry Using the Lean Tool SMED. In Procedia Manufacturing; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 41, pp. 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leming-Lee, T.S.; Polancich, S.; Pilon, B. The Application of the Toyota Production System LEAN 5S Methodology in the Operating Room Setting. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 54, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Lin, P.; Guo, D.; Huang, G.Q. Towards Zero-Warehousing Smart Manufacturing from Zero-Inventory Just-In-Time Production. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 64, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, A.; Ducq, Y. Lean Practices Implementation in Aerospace Based on Sector Characteristics: Methodology and Case Study. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 1313–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marodin, G.; Frank, A.G.; Tortorella, G.L.; Netland, T. Lean Product Development and Lean Manufacturing: Testing Moderation Effects. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 203, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, R.T. Identifying and Eliminating the Seven Wastes or Muda; Asian Institute of Management: Makati, Philippines, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Carrillo-Gutiérrez, T.; Ravelo, G. Applying the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle to Reduce the Defects in the Manufacturing Industry. A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinodh, S.; Arvind, K.R.; Somanaathan, M. Tools and Techniques for Enabling Sustainability through Lean Initiatives. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2011, 13, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehin, A.; Zwolinski, P.; Brissaud, D. A Tool to Implement Sustainable End-of-Life Strategies in the Product Development Phase. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Luthra, S.; Huisingh, D.; Mangla, S.K.; Narkhede, B.E.; Liu, Y. Development of a Lean Manufacturing Framework to Enhance Its Adoption within Manufacturing Companies in Developing Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao, R.; Sarache, W.; Gómez, I. Lean Manufacturing and Sustainable Performance: Trends and Future Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, T. The Benefits of Lean Manufacturing: What Lean Thinking Has to Offer the Process Industries. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2005, 83, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azzi, A.; Battini, D.; Faccio, M.; Persona, A. Mixed model assembly system with multiple secondary feeder lines: Layout design and balancing procedure for ATO environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 5132–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olhager, J. Strategic Positioning of the Order Penetration Point. In International Journal of Production Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 85, pp. 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.G.; Gallego-García, S.; García-García, M. Development of a Pull Production Control Method for ETO Companies and Simulation for the Metallurgical Industry. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, D.; Strandhagen, J.O.; Tommelein, I.; Ballard, G.; Rossi, M. A New Set of Principles for Pursuing the Lean Ideal in Engineer-To-Order Manufacturers. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 17, pp. 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.; Khalid, Q.S.; Abas, M.; Li, H.; Azim, S.; Babar, A.R.; Saleem, W.; Khan, R. Implementation of POLCA Integrated QRM Framework for Optimized Production Performance—A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, F.; Dallasega, P. Barriers to lean implementation in engineer-to-order manufacturing with subsequent assembly on-site: State of the art and future directions. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Moghadam, M.; Safari, H.; Maleki, M. A Novel Model for Business Process Maturity Assessment through Combining Maturity Models with EFQM and ISO 9004: 2009. Int. J. Bus. Process Integr. Manag. 2003, 6, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou-Llusar, J.C.; Escrig-Tena, A.B.; Roca-Puig, V.; Beltrán-Martín, I. An Empirical Assessment of the EFQM Excellence Model: Evaluation as a TQM Framework Relative to the MBNQA Model. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolen, T.L.; Hacker, M.E. A Review of Lean Assessment in Organizations: An Exploratory Study of Lean Practices by Electronics Manufacturers. J. Manuf. Syst. 2005, 24, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdil, F.; Leonard, K.M. Criteria for a Lean Organisation: Development of a Lean Assessment Tool. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 4587–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Almomani, M.; Abdelhadi, A.; Mumani, A.; Momani, A.; Aladeemy, M. A Proposed Integrated Model of Lean Assessment and Analytical Hierarchy Process for a Dynamic Road Map of Lean Implementation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 72, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cil, I.; Turkan, Y.S. An ANP-Based Assessment Model for Lean Enterprise Transformation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 64, 1113–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, D.; Mize, J. Development of a Lean Enterprise Transformation Maturity Model. Inf. Knowl. Syst. Manag. 2002, 3, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Initiative, L.A. LAI Enterprise Self-Assessment Tool (LESAT) V.2 Facilitator’s Guide; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Vaishya, R. Real-Time Monitoring System to Lean Manufacturing. In Procedia Manufacturing; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 20, pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Standard ISO Quality Management—Quality of an Organization—Guidance to Achieve Sustained Success. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9004:ed-4:v1:en (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Krijnen, A. The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer. Action Learn. Res. Pract. 2007, 4, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L.J. Application of the New Production Philosophy to Construction Construction Management in Refurbishment Projects View Project Energy and Cost Efficient Design of Buildings View Project; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Toyota Product Development System: Integrating People, Process, and ... -James Morgan, Jeffrey, K. Liker-Google Libri. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?hl=it&lr=&id=K0EHEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT12&ots=viri-SUuWu&sig=p-tbKsDErG504m7WBTMZRqVTops&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Earl, G.; Clift, R. Stakeholder Value Analysis: A Methodology for Intergrating Stakeholder Values into Corporate Enviromental Investment Decisions. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 1999, 8, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S.R.; Aziz, A.A.; Shuhidan, S.M.; Aziz, A.A.; Mokhsin, M. SMEs Maturity Model Assessment of IR4.0 Digital Transformation. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 739, pp. 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettemich, J.; Böllhoff, J.; Seifeimami, S.; Beck, S. Volume and Mix Flexibility Evaluation of Lean Production Systems. Procedia CIRP 2013, 9, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mikkola, J.H. Mdoularization Assesment of Product Architecture. In Proceedings of the DRUID Winter Conference, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 7–8 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, R.L.; Lim, S. Improving Flow to Achieve Lean Manufacturing in Shipbuilding. Prod. Plan. Control 1999, 10, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C.; Hlström, P. Assessing Changes towards Lean Production. In International Journal of Operations and Production Management; MCB UP Ltd: Bingley, UK, 1996; pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Úbeda, J.A.; de Burgos-Jiménez, J.; Carmona-Moreno, E. Measuring Stakeholder Integration: Knowledge, Interaction and Adaptational Behavior Dimensions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.; Krause, A.; Provencher, J.; Seltzer, T. Transparency Tested: The Influence of Message Features on Public Perceptions of Organizational Transparency. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundeliene, K.; Leitoniene, S. Business Information Transparency: Causes and Evaluation Possibilities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, L.T.; Cheney, G. Peering into Transparency: Challenging Ideals, Proxies, and Organizational Practices. Commun. Theory 2015, 25, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Klotz, E.; Newman, S.T. Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodh, S.; Kuttalingam, D. Computer-Aided Design and Engineering as Enablers of Agile Manufacturing: A Case Study in an Indian Manufacturing Organization. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2011, 22, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.; Riezebos, J.; Strandhagen, J.O. Lean Production and ERP Systems in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: ERP Support for Pull Production. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO-ISO 9001:2015-Quality Management Systems—Requirements. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62085.html (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Jagtap, M.; Teli, S.N. PDCA Cycle as TQM Tool-continuous improvement of warranty. Int. J. Recent Technol. Mech. Electr. Eng. (IJRMEE). 2015, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Caffyn, S. Development of a Continuous Improvement Self-Assessment Tool. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1999, 19, 1138–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, E.; Dallasega, P.; Matt, D.T. Critical Factors for Introducing Lean Product Development to Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in Italy. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 60, pp. 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mast, J.; Lokkerbol, J. An analysis of the Six Sigma DMAIC method from the perspective of problem solving. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 139, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.T.; Ogden, J.A.; Boehmke, B.C. A Quantified Kraljic Portfolio Matrix: Using Decision Analysis for Strategic Purchasing. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018, 24, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.F.; Ellram, L.M. A Portfolio Approach to Supplier Relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzetta, M.; Rossi, A.; Puppato, A. Modelling activity times by hybrid synthetic method. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Vila, Y.; Lusiani, F.; Barsotti, L.; Sani, L.; Ceccarelli, P.; Lanzetta, M. Embedded smart sensor device in construction site machinery. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Persona, A.; Sgarbossa, F.; Zanin, G. Multi-stage supply network design in case of reverse flows: A closed-loop approach. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 12, 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongrassamee, S.; Simmons, J.E.L.; Gardiner, P.D. Performance measurement tools: The Balanced Scorecard and the EFQM Excellence Model. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2003, 7, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ETO Lean Principles | |

|---|---|

| P1. | Defining Stakeholders Value |

| P2. | Leadership, People and Learning |

| P3. | Flexibility |

| P4. | Modularization |

| P5. | Continuous flow process |

| P6. | Demand Pull |

| P7. | Stakeholders and System Integration |

| P8. | Transparency |

| P9. | Technology |

| P10. | Continuous Improvement |

| ETO Lean Principles | Lean Maturity Criteria | [Ref.], (Section) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Score | [0–20%) | [20–40%) | [40–60%) | [60–80%) | [80–100%) | |

| Level | Negligible | Low | Medium | High | Full | |

| P1. * | (i) Stakeholders identification | (i) Identification and assignment of the (key) performance attributes or values to the stakeholder group. | (i) Definition of value weights through Pairwise Comparison Model, Stakeholders Cluster Method, or others. | (i) Calculation of a total value index for each option being assessed by the analysis. | (i) Satisfaction of the main concerns of the stakeholders as well as the creation of a new option, possibly based on those originally considered. | [46], (Section 2.1.1) |

| P2. * | (i) Level of commitment among senior leaders and management is variable. Some endorse, while others may actively resist. (ii) Employee competencies are at beginner level and call for theoretical training. | (i) Senior management buys into group commitment and engages in the transformation process. (ii) Minimum knowledge of lean philosophy with applications in standard parts of the production process. | (i) Senior managers personally and visibly lead enterprise transformation. (ii) Complete knowledge of lean principles with application over entire production process, including training on the job. | (i) Senior leaders are championing the transformation within the enterprise. (ii) Conclusion training on the job and beginner implementation of lean techniques across the entire company. | (i) Senior leaders and management mentor and foster transformation champions internally and throughout the extended enterprise. (ii) Complete knowledge of lean techniques at all the company levels. | [39,40,47], (Section 2.1.2.) |

| P3. | Formula (1) | [48], (Section 2.1.3.) (Section 2.3.1.) | ||||

| (i)Long lead times for customization (ii) Low capacity of adaptation for customers’ needs. | (i) Moderate lead times for customization. (ii) Limited capacity of adaptation for customers’ needs. | (i) Average lead times for customization (high volumes and mix). (ii) Average capacity of adaptation for customers’ needs. | (i) Limited lead times for customization (ii) Moderate capacity of adaptation for customers’ needs. | (i) The lead time between customer demand dates and production dates are zero (ii) Complete flexibility of volumes and mix. | ||

| P4. | Formula (2) | [49], (Section 2.1.4.) (Section 2.3.2.) | ||||

| Product architecture is composed of new components with low replacement, allowing customer minimum mixing and matching. | Product architecture is composed of higher numbers of new components and lower numbers of standard components, with limited replacement degrees. | Product architecture is composed of both new components and standard components with average replacement degrees. | Product architecture is composed of lower number of new components and higher numbers of standard components, with moderate replacement degrees. | Product architecture is composed of standard components with higher replacement degrees, allowing clients higher opportunities for mixing and matching. | ||

| P5. | Formula (3) | [50], (Section 2.1.5.) (Section 2.3.3.) | ||||

| Elevated WIP and defects. | Moderate level WIP and defects | Average level WIP and defects. | Low level WIP and defects | No WIP. The process flow is continuous without obstacles or waste. | ||

| P6. | Formula (4) | [51], (Section 2.1.6.) (Section 2.3.4.) | ||||

| Order triggers delivery. The prior activities are forecast-based. | Order triggers packaging. The prior activities are forecast-based | Order triggers assembly. The prior activities are forecast-based | Order triggers purchasing. The prior activities are forecast-based | Order triggers engineering; zero activities are forecast-driven | ||

| P7. * | (i) The company identified all the stakeholders. (ii) The company frequently has meetings with thestakeholders. | (i)The company consults the stakeholders and asks them for information before making decisions. | (i) The company’s formal or informal cooperation with the stakeholders is intense (commitments, collaboration agreements, etc.) | (i) Stakeholder participation in the company’s decisions is formal and includes quantitatively relevant information. | The company: (i) strives to develop new contacts with all stakeholders, and (ii) dedicates time and resources to assessing and prioritizing the demands of the different stakeholders. | [51,52], (Section 2.1.7.) |

| P8. * | (i) Information divulgations are lacking. (ii) Stakeholders lack a clear message and comprehension. | (i) Starting communication between various stakeholders and departments of the company (exchange of elementary information). | (i) Average level of information disclosure, clarity, and accuracy among all the interested parties. | (i) High level of information disclosure, clarity, and accuracy among all the interested parties (informal). | (i) Formal disclosure to all stakeholders through complete clarity as well as accuracy of information. | [53,54,55], (Section 2.1.8.) |

| P9. * | (i) Understand i4.0 enablers. (ii) Research on technology applications. | (i) Promotion and implementation of i4.0 project for digitalization (hardware/software) | (i) Average digitalization of the processes through the product life cycle (CAE). | (i) Managerial systems (e.g., ERP). (ii) Smart factory systems (MES) | (i) Avant-garde technology, as well as a degree of automation. (ii) Extensive cover of i4.0 enablers | [56,57,58], (Section 2.1.9.) |

| P10. * | (i) Senior leaders and management understand the continuous improvement philosophy. (ii) Awareness of current situation | (i) Study of tools and techniques proposed by continuous improvement and lean methodologies as well (e.g., problem-solving). | (i) Structured objective, goal-oriented continuous improvement. | (i) Proactive continuous improvement, including application and monitoring of lean tools and methodologies. | (i) Senior leaders spread the continuous improvement philosophy and methodologies throughout the organization. | [51,59,61], (Section 2.1.10.) |

| ETO Lean Principle | Evidences | Lean Maturity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Score | ||

| P1. * | Little clarity in the stakeholders’ roles in the company emerged. Absence of an organizational chart. | 2 | 30% |

| P2. * | The management is responsibly committed to the achievement of goals and promotes active training on the job. | 4 | 70% |

| P3. | The company adapts to customer requests easily. Result from (1) | 5 | 100% |

| P4. | The reuse of standard solutions or parts to produce special machines is common practice. Result from (2) | 5 | 80% |

| P5. | Result from (3) | 5 | 88% |

| P6. | For the machines analyzed, the assembly process starts after receiving the customer orders. Result from (4) | 4 | 60% |

| P7. * | The company consults the interested parties before making decisions. Meetings are by department, not collective. | 3 | 40% |

| P8. * | Average level of disclosure. There is no standard, tested system for information disclosure. | 4 | 60% |

| P9. * | The company uses a specific management software (anonymized). The management software includes the customer orders, insertion of the bills of materials and the purchase of the materials necessary for production. Commercial CAD software is implemented. | 5 | 80% |

| P10. * | Senior leaders and management are aware of the continuous improvement philosophy, but lean tools and methods are not actually implemented. | 2 | 20% |

| OVERALL | Ten criteria average value | 4 | 63% |

| Product Type | di | pi |

|---|---|---|

| Model A | 13 | 13 |

| Model B | 16 | 16 |

| Model C | 10 | 10 |

| Model D | 15 | 15 |

| Subcircuits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Vacuum Switch | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Sensor | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Big Case | 1 | 10 | 10 | 1 |

| Motor | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Mechanical Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Head | 26 | 13 | 2 |

| Rear Head | 15 | 10 | 1.5 |

| Vacuum Switch Support | 21 | 17 | 1.25 |

| Micro Support | 34 | 17 | 2 |

| Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT |

| Percentage [%] | WIP [pcs] |

|---|---|

| 100 | 1 |

| 80 | 1.2 |

| 60 | 1.4 |

| 40 | 1.6 |

| 20 | 1.8 |

| 0 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiera, M.; Lupi, F.; Rossi, A.; Lanzetta, M. Lean Maturity Assessment in ETO Scenario. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11093833

Chiera M, Lupi F, Rossi A, Lanzetta M. Lean Maturity Assessment in ETO Scenario. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(9):3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11093833

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiera, Mariastella, Francesco Lupi, Andrea Rossi, and Michele Lanzetta. 2021. "Lean Maturity Assessment in ETO Scenario" Applied Sciences 11, no. 9: 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11093833

APA StyleChiera, M., Lupi, F., Rossi, A., & Lanzetta, M. (2021). Lean Maturity Assessment in ETO Scenario. Applied Sciences, 11(9), 3833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11093833