Use of Consumer Neuroscience in the Choice of Aromatisation as Part of the Shopping Atmosphere and a Way to Increase Sales Volume

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Retail Atmospherics

1.2. Olfactory Atmospherics

1.3. Consumer Neuroscience

2. Materials and Methods

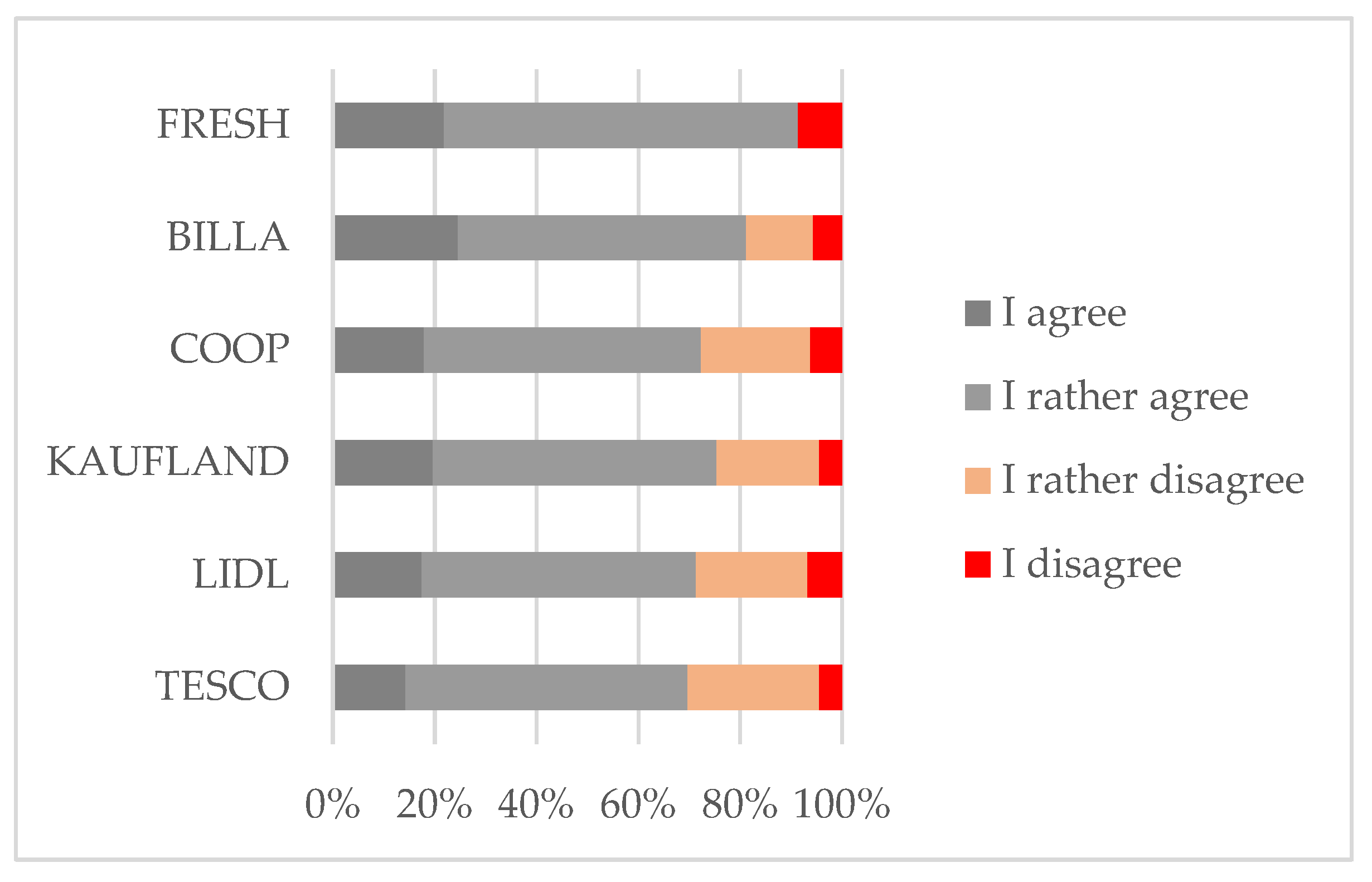

2.1. Stage 1—Quantitative Survey of Perception of Shopping Atmosphere in Slovakia

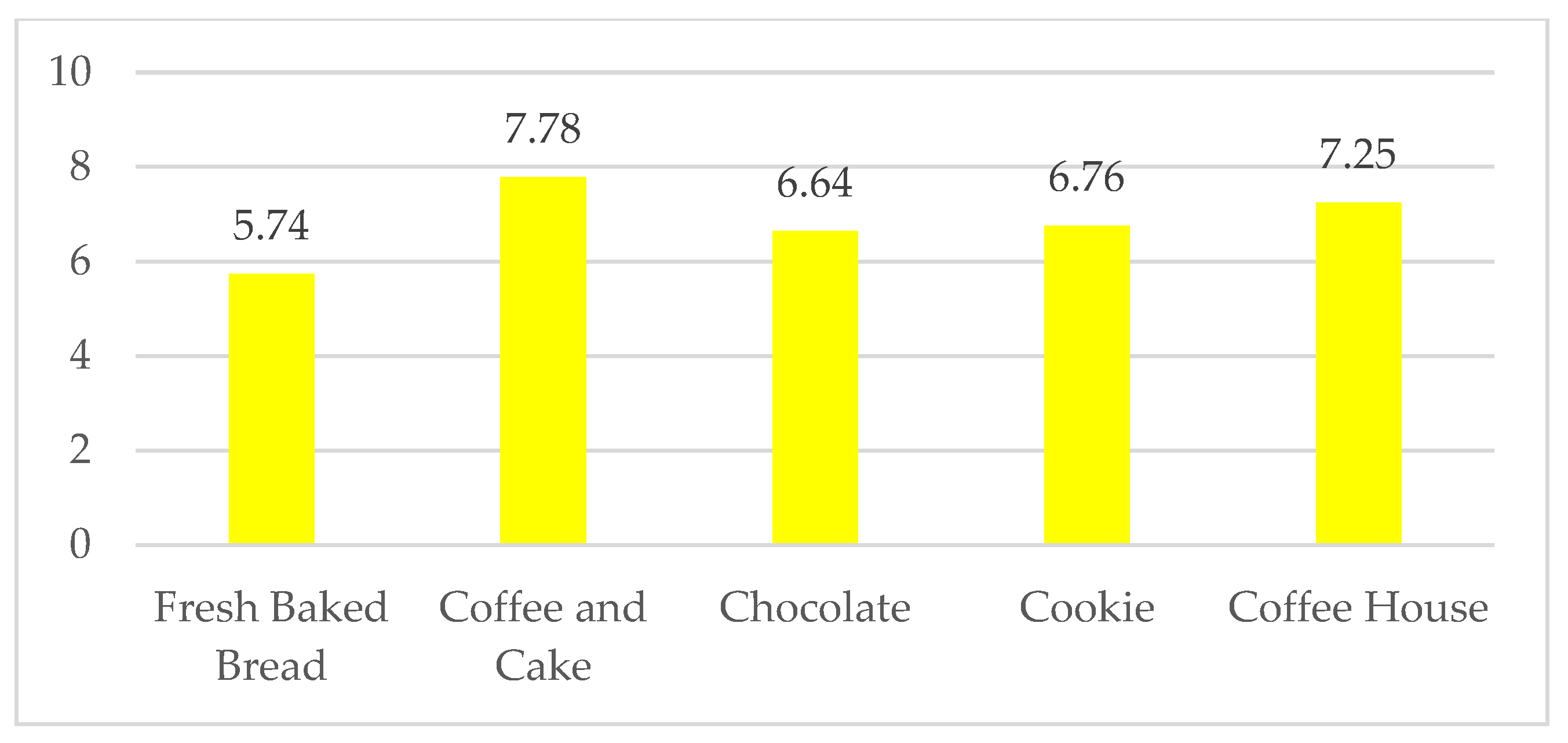

2.2. Stage 2—Testing in Laboratory Conditions Using EEG and Face Reading (FA)

- Initial instruction of respondents, completion of consent to biometric and neuroimaging testing, as well as the processing of personal data in accordance with the GDPR and the Code of Ethics of Sociological Surveys.

- Olfactory sensitivity threshold test.

- Entry-driven interview in the form of CAPI.

- Tests of selected aromas using consumer neuroscience and aromatising box tools.

- Interview in the form of CAPI.

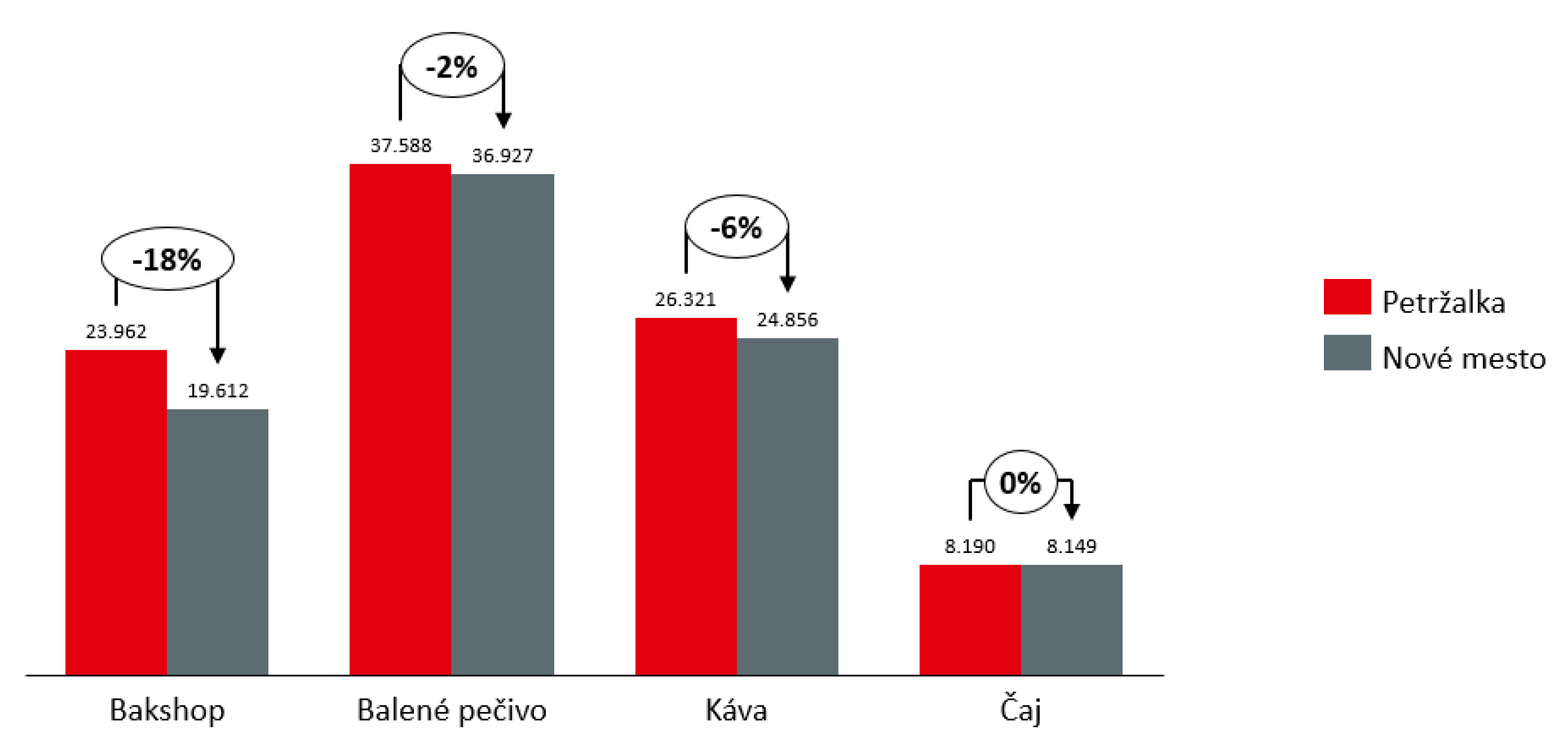

2.3. Stage 3—Experiment on the Influence of Aromas on Consumer Behaviour in Real Conditions

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moon, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Determinants of consumers’ online/offline shopping behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L.; Nordfält, J. The Future of Retailing. J. Retail. 2017, 93, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angula, E.; Zulu, V.M. Tackling the ‘death’ of brick-and-mortar clothing retailers through store atmospherics and customer experience. Innov. Mark. 2021, 17, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecointre-Erickson, D.; Adil, S.; Daucé, B.; Legohérel, P. The role of brick-and-mortar exterior atmospherics in post-COVID era shopping experience: A systematic review and agenda for future research. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I.; Gilboa, S.; Mitchell, V. Experiencing atmospherics: The moderating effect of mall experiences on the impact of individual store atmospherics on spending behavior and mall loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschk, H.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Breitsohl, J. Calibrating 30 Years of Experimental Research: A Meta-Analysis of the Atmospheric Effects of Music, Scent, and Color. J. Retail. 2017, 93, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puccinelli, N.M.; Goodstein, R.C.; Grewal, D.; Price, R.; Raghubir, P.; Stewart, D. Customer Experience Management in Retailing: Understanding the Buying Process. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, B.; Aradhya S, G.B.; Kumar TK, S.; Kumar, B.S.; Shankar, M.S. Impact of Consumer Behavior Based on Store Atmospherics. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 480–492. [Google Scholar]

- Berčík, J. Príjemná Nákupná Atmosféra ako Konkurenčná Výhoda. Available online: https://www.tovarapredaj.sk/2021/06/09/jakub-bercik-prijemna-nakupna-atmosfera-ako-konkurencna-vyhoda/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Spence, C.; Puccinelli, N.M.; Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L. Store atmospherics: A multisensory perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soars, B. Driving sales through shoppers’ sense of sound, sight, smell and touch. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D. Sensory Aspects of Retailing: Theoretical and Practical Implications. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, B.M.L. Sensory Cues as Retailing Innovations: The case of Media Markt. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 1, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvari, G.; Kelemen-Erdos, A. An Exploration of Sensory Marketing in Fast-Fashion Retailing. In Proceedings of the FIKUSZ Symposium for Young Researchers, Budapest, Hungary, 30 November 2018; pp. 484–493. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Muñoz, C.; Arribas Pérez, F.; Martín Zapata, C. Sensory marketing in the women’s fashion sector: The smell of the shops in Madrid. RAN Rev. Acad. Neg. 2021, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.R.M.; Jetti, E.R. Scent Marketing—Harnessing the Power of Scents in stimulating senses of Organized Retail Consumers and Employees. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durai, T.; Stella, G. Store atmospherics: An effort to influence impulse buying in brick and mortar stores. Int. J. Sales Mark. Manag. 2020, 10, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Errajaa, K.; Legohérel, P.; Daucé, B.; Bilgihan, A. Scent marketing: Linking the scent congruence with brand image. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 402–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera-Torrell, O.; León, I.Á.; Cappai, A.; Antolín, G.S. Do ambient scents in hotel guest rooms affect customers’ emotions? Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Botelho, D. Olfactory priming on consumer categorization, recall, and choice. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gómez, F.I.; Miranda-Gonzalez, F.J.; Mayo, J.P.; González-López, Ó.R.; Pascual-Nebreda, L. The scent of art. perception, evaluation, and behaviour in amuseum in response to olfactorymarketing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Girona-Ruíz, D.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; López-Lluch, D.; Esther, S. Aromachology related to foods, scientific lines of evidence: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Kahn, B.E.; Knasko, S.C. There’s Something in the Air: Effects of Congruent or Incongruent Ambient Odor on Consumer Decision Making. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Crowley, A.E.; Henderson, P.W. Improving the store environment: Do olfactory cues affect evaluations and behaviors? J. Mark. 1996, 60, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrin, M.; Ratneshwar, S. Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.M.; Yah, X.; Yoh, E. Effects of a product display and environmental fragrancing on approach responses and pleasurable experiences. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinitzky, G.; Mazursky, D. The effects of cognitive thinking style and ambient scent on online consumer approach behavior, experience approach behavior, and search motivation. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 496–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Pierański, B.; Borusiak, B. Aromachology and customer behavior in retail stores: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Botelho, D. The unconscious perception of smells as a driver of consumer responses: A framework integrating the emotion-cognition approach to scent marketing. AMS Rev. 2021, 11, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčík, J.; Neomániová, K.; Gálová, J.; Mravcová, A. Consumer neuroscience as a tool to monitor the impact of aromas on consumer emotions when buying food. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčík, J.; Mravcová, A.; Gálová, J.; Mikláš, M. The use of consumer neuroscience in Aroma marketing of a service company. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčík, J.; Virágh, R.; Kádeková, Z.; Duchoňová, T. Aroma Marketing As A Tool To Increase Turnover In A Chosen Business Entity. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berčík, J.; Gálová, J.; Vietoris, V.; Paluchová, J. The Application of Consumer Neuroscience in Evaluating the Effect of Aroma Marketing on Consumer Preferences in the Food Market. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Casado-Aranda, L.A.; Bastidas-Manzano, A.B. Consumer neuroscience techniques in advertising research: A bibliometric citation analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țichindelean, M.; Țichindelean, M.T.; Cetină, I.; Orzan, G. A comparative eye tracking study of usability—towards sustainable web design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzani, A.; Ravaioli, S.; Trieste, L.; Faraguna, U.; Turchetti, G. Is EEG Suitable for Marketing Research? A Systematic Review. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 594566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Baharun, R.; Alharthi Rami Hashem, E.; Mansor, A.A.; Ali, J.; Abbas, A.F. Neuroimaging techniques in advertising research: Main applications, development, and brain regions and processes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Freudenreich, T.; Yu, W.; Pelowski, M.; Liu, T. Methodological structure for future consumer neuroscience research. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, A.A.; Isa, S.M. Fundamentals of neuromarketing: What is it all about? Neurosci. Res. Notes 2020, 3, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuvaran, M.; Gomathi, S. Consumer Neuroscience and its Application in Marketing. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagyová, Ľ.; Berčík, J.; Džupina, M.; Hazuchová, N.; Holotová, M.; Kádeková, Z.; Koprda, T.; Košičiarová, I.; Récky, R.; Rybanská, J. Marketing II; Slovenská Poľnohospodárska Univerzita: Nitra, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsøy, T.Z. A foundation for consumer neuroscience and neuromarketing. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 59, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedziela, M.M.; Ambroze, K. The future of consumer neuroscience in food research. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 92, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Genco, S.J.; Pohlmann, A.P.; Steidl, P. Neuromarketing for Dummies; John Wiley&Sons: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alvino, L.; Pavone, L.; Abhishta, A.; Robben, H. Picking Your Brains: Where and How Neuroscience Tools Can Enhance Marketing Research. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 577666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszkiel, S. Data Acquisition Methods for Human Brain Activity. In Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 852. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. Demystifying neuromarketing. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, N.A.; Mousikou, P.; Mahajan, Y.; de Lissa, P.; Thie, J.; McArthur, G. Validation of the Emotiv EPOC® EEG gaming systemfor measuring research quality auditory ERPs. PeerJ 2013, 1, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duvinage, M.; Castermans, T.; Petieau, M.; Hoellinger, T.; Cheron, G.; Dutoit, T. Performance of the Emotiv Epoc headset for P300-based applications. Biomed. Eng. Online 2013, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hairston, W.D.; Whitaker, K.W.; Ries, A.J.; Vettel, J.M.; Bradford, J.C.; Kerick, S.E.; McDowell, K. Usability of four commercially-oriented EEG systems. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 046018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, N.I.; Kordupleski, R.E. Good and bad market research: A critical review of Net Promoter Score. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2019, 35, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karr, D. Leveraging Al in Market Research. Available online: https://martech.zone/groupsolver-ai-nlp-market-research (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Krbot Skorić, M.; Adamec, I.; Jerbić, A.B.; Gabelić, T.; Hajnšek, S.; Habek, M. Electroencephalographic Response to Different Odors in Healthy Individuals: A Promising Tool for Objective Assessment of Olfactory Disorders. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2015, 46, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chovancová, Ľ. Vianočné Pozdravy. Prvý čuchový Test Vianočných vôní. EEG Meranie v Kombinácii s Facereaderom; Agentúra 2Muse: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ESOMAR. 36 Questions to Help Commission Neuroscience Research 2012. Available online: https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ESOMAR_36-Questions-to-hel-commission-neuroscience-research.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Electrode Position Nomenclature Committee. Guideline thirteen: Guidelines for standard electrode position nomenclature. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1994, 11, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwer, M.R.; Comi, G.; Emerson, R.; Fuglsang-Frederiksen, A.; Guerit, M.; Hinrichs, H.; Ikeda, A.; Luccas, F.J.C.; Rappelsburger, P. IFCN standards for digital recording of clinical EEG. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998, 106, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, S.; Sclocco, R.; Barbieri, R.; Reni, G.; Zucca, C.; Bianchi, A.M. EEG-based Index for Engagement Level Monitoring during Sustained Attention. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; IEEE: Glasgow, UK, 2015; Volume 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stikic, M.; Berka, C.; Levendowski, D.J.; Rubio, R.; Tan, V.; Korszen, S.; Barba, D.; Wurzel, D. Modeling temporal sequences of cognitive state changes based on a combination of EEG-engagement, EEG-workload, and heart rate metrics. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berka, C.; Levendowski, D.J.; Lumicao, M.N.; Yau, A.; Davis, G.; Zivkovic, V.T.; Olmstead, R.E.; Tremoulet, P.D.; Craven, P.L. EEG correlates of task engagement and mental workload in vigilance, learning, and memory tasks. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2007, 78, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Abler, B.; Walter, H.; Erk, S. Neural correlates of frustration. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, B.A.; Holroyd, T.; Carver, F.W.; Onelio, L.M.; Mendoza, J.K.; Cornwell, B.R.; Fox, N.A.; Pine, D.S.; Coppola, R.; Leibenluft, E. A preliminary study of the neural mechanisms of frustration in pediatric bipolar disorder using magnetoencephalography. Depress. Anxiety 2010, 27, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deveney, C.M.; Connolly, M.E.; Haring, C.T.; Bones, B.L.; Reynolds, R.C.; Kim, P.; Pine, D.S.; Leibenluft, E. Neural mechanisms of frustration in chronically irritable children. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noldus Information Technology Reference Manual—FaceReader Version 7. 2010. Available online: http://sslab.nwpu.edu.cn/uploads/1500604789-5971697563f64.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Skiendziel, T.; Rösch, A.G.; Schultheiss, O.C. Assessing the convergent validity between the automated emotion recognition software Noldus FaceReader 7 and Facial Action Coding System Scoring. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maison, D.; Pawłowska, B. Using the Facereader Method to Detect Emotional Reaction to Controversial Advertising Referring to Sexuality and Homosexuality. In Neuroeconomic and Behavioral Aspects of Decision Making; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, P.H.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Willemsen, A.; Meyer, E.S.; Noldus, L.P.J.J. The observer XT: A tool for the integration and synchronization of multimodal signals. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noldus Information Technology Reference Manual—FaceReader Version 7. 2020. Available online: https://www.noldus.com/facereader/benefits (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Panovská, Z.; Ilko, V.; Doležal, M. Air quality as a key factor in the aromatisation of stores: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Institute for Fragrance Materials. Available online: https://www.rifm.org/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- International Fragrance Association. Available online: https://ifrafragrance.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Goldkuhl, L.; Styvén, M. Sensing the scent of service success. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzharov, A.V.; Block, L.G.; Morrin, M. The cool scent of power: Effects of ambient scent on consumer preferences and choice behavior. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Principles of good practice. In Sensory Evaluation of Food; Food Science Text Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Wisenblit, J. Consumer Behavior, 12th ed.; Pearson English Readers: London, UK, 2019; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, M.; Bechara, A. The somatic marker framework as a neurological theory of decision-making: Review, conceptual comparisons, and future neuroeconomics research. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.R. Effects of ambient odors on slot-machine usage in a las vegas casino. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just for the Smell of It. Available online: www.financialperspectives.biz/perspectives-investment-blog/ygtxsmb3nrm7nkzcxs6kyykknpczxf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Builder, M. Smelling Cookies Makes You More Likely to Buy Coffee. Smelling Cookies Makes You More Likely to Buy Coffee. Available online: https://www.myrecipes.com/extracripsy/you-have-to-take-a-test-to-buy-this-145-bottle-of-coffee-liquer (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Domracheva, M.; Kulikova, S. EEG correlates of perceived food product similarity in a cross-modal taste-visual task. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 85, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, L.; Bentivegna, H.; Nicklaus, S.; Monnery-Patris, S.; Chambaron, S. Non-Conscious Effect of Food Odors on Children’s Food Choices Varies by Weight Status. Front. Nutr. 2017, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Venkatraman, V.; Dimoka, A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Vo, K.; Hampton, W.; Bollinger, B.; Hershfield, H.E.; Ishihara, M.; Winer, R.S. Predicting advertising success beyond traditional measures: New insights from neurophysiological methods and market response modeling. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stasi, A.; Songa, G.; Mauri, M.; Ciceri, A.; Diotallevi, F.; Nardone, G.; Russo, V. Neuromarketing empirical approaches and food choice: A systematic review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, I.; García-Madariaga, J.; Blasco, M.-F. What Can Neuromarketing Tell Us about Food Packaging? Foods 2020, 9, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Neuroscience-Inspired Design: From Academic Neuromarketing to Commercially Relevant Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2019, 22, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.E.; Chin, L.; Klitzman, R. Defining neuromarketing: Practices and professional challenges. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, D.; Iorga, A.; Wolter, L.; Znanewitz, J. Conducting neuromarketing studies ethically-practitioner perspectives. Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1320858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, O.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Digital Sensory Marketing: Integrating New Technologies Into Multisensory Online Experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newell, B.R.; Shanks, D.R. Unconscious influences on decision making: A critical review. Behav. Brain Sci. 2014, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Fresh Baked Bread | Coffee and Cake | Chocolate | Cookies | Coffee House | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee House | H5 | H4 | H4 | H4 | |

| Cookies | H4 | H4 | H4 | ||

| Chocolate | H4 | H4 | |||

| Coffee and Cake | H5 | ||||

| Fresh Baked Bread |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berčík, J.; Neomániová, K.; Mušinská, K.; Pšurný, M. Use of Consumer Neuroscience in the Choice of Aromatisation as Part of the Shopping Atmosphere and a Way to Increase Sales Volume. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147069

Berčík J, Neomániová K, Mušinská K, Pšurný M. Use of Consumer Neuroscience in the Choice of Aromatisation as Part of the Shopping Atmosphere and a Way to Increase Sales Volume. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(14):7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147069

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerčík, Jakub, Katarína Neomániová, Kristína Mušinská, and Michal Pšurný. 2022. "Use of Consumer Neuroscience in the Choice of Aromatisation as Part of the Shopping Atmosphere and a Way to Increase Sales Volume" Applied Sciences 12, no. 14: 7069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12147069