1. Introduction

The three middle ear ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which are the smallest bones of the human body, are organized as a sound-conducting chain that connects the tympanum to the cochlea [

1]. Trauma, cancer surgery, or congenital malformations may lead to partial hear loss or total deafness, requiring ossicles replacement. Due to the highly personalized anatomy of these ossicles and of the surrounding tissues, finding cadaveric (or, even less available, from living donors) replacements to match them for heterologous transplantation is very difficult [

2]. Besides using ossicles from humans, the most widely utilized method to restore conductive hearing is currently their total or partial replacement with a biocompatible metal implant [

3], the most commonly used being titanium implants [

4]. However, the choices of commercial prothesis for ossicle replacement are limited to a few standard shapes and sizes, determined by the manufacturers.

Besides metal bars, ceramic bridges have also been considered, showing good initial benefits but a high failure rate [

5]. However, there is substantial interest in working with these materials, given that albeit fragile, these are mechanically quite sturdy when compact. More importantly, porous ceramics could be incorporated into osteogenic multi-material constructs and even potentially transformed in vitro into bone-like structures [

6].

With the advent of additive manufacturing and its medical applications, new avenues have been opened to solve the issue of ossicles availability, both for prosthetics (mainly by 3D printing) and for bio-implantology (by 3D bioprinting). Yet, surprisingly, the progress on these lines has been slow and limited so far to the early steps of high-resolution image acquisition [

7] and CAD model generation [

8], as well as to additive manufacturing with plastic materials, which are useful only for modeling or surgical planning [

9].

Here, we sought to develop more realistic aspects of the additive manufacturing technology by testing the available design and implementation options using biomaterials that are likely to be of value for next-generation biological, personalized otic implants. The current study is among the first ones to explore the use of 3D printing for the generation of ossicle models from biologically relevant materials such as osteogenic ceramics and hydrogels for bioprinting (bioinks), with the potential to be used in hearing restoration applications.

This possibility was created by the availability of a printable (or ‘plottable’) calcium phosphate/hydroxyapatite cement (CPC) paste, also called ‘Osteoink’ [

6], whose composition is close to that of human bone minerals [

10]. Osteoink was specifically designed for 3D printers [

11] and thus has been already assessed for osteo-inductive properties in vivo, when printed as a porous structure [

6].

The goal of this study was to assess the suitability of solid (CPC ceramic) and soft (alginate-based) biomaterials for the 3D printing of anatomically realistic models of human ear ossicles. To the best of our knowledge, work in this field has not been published yet, although there are precedents of creating implantable ceramic bridges for ossicle chain repair [

5] or printing ossicle models with plastic materials [

9].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virtual Models of the Human Ear Ossicles

Open-source models of the human middle ear ossicles were found ready for downloading in different file formats [

12]. The models had an initial resolution of 2048 × 2048 pixels with 34.4 µm pixel and voxel size. The STL files represent a detailed 3D image of the ossicles, which we verified by comparison with other published studies [

13,

14]. As the images in these files were 100× oversized with respect to the anatomic object, to perform the scale reduction we employed either Meshmixer v3.5.474 (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA, USA;

https://www.meshmixer.com/; accessed on 20 September 2020) or BioCAM, the software of our BioFactory bioprinter (REGENHU, Villaz-St-Pierre, Switzerland) [

15].

2.2. 3D Printing of Ossicle Models with a Ceramic Paste

To create models for printing with the viscous CPC paste on a solid flat base, the first two layers of the models were removed using the BioCAD software (REGENHU), thus creating a flat bottom layer. Models were also printed directly on glass slides by splitting ossicle models in two halves then assembling them after solidification by an adhesive. To create the halves, the CAD models of the incus and malleus were separated in two parts either by applying a plane cut using Meshmixer software, or by exporting the model to BioCAD and deleting half of the layers. Due to its small size, the stapes model was not printed in halves but rather directly on glass surfaces by creating a flat bottom with sculpting tools and a plane cut within the Meshmixer software.

The ceramic constructs were created with the extrusion printhead of the bioprinter, using a commercially available CPC (Innotere, Radebeul, Germany). For printing the solid or halved ossicle models, a 0.20 mm internal diameter (ID) plastic conical nozzle (REGENHU) was utilized with BioCAM software material settings of 0.26 mm nozzle diameter, 4 mm/s feed rate, 0.15 mm layer height, and 100% overlapping perimeter, as well as a pressure extrusion of 169 MPa. Porous models were also printed using a 0.20 mm ID plastic conical nozzle, and the print path was generated by setting the outer perimeter loops to 0 and the infill pattern type to rectilinear at 36% infill density. Porous models were printed using BioCAM software’s material settings of 0.25 mm nozzle diameter, 3 mm/s feed rate, 0.25 mm layer height, 15% overlapping perimeter, and a pressure extrusion of 169 MPa. To inspect the accuracy of the porous grid pattern in the printed structures, the porous models were visualized with the 4× objective of an Eclipse TS 100 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Embedded Printing of the Ceramic Paste in a Supporting Hydrogel

Printing with a viscous paste such as Osteoink on a solid support raised the issue of shape preservation (given the rather complex anatomic structure of the ossicles required for implantation [

8]). To address this problem, we employed a bioprinting method in a supporting bath [

16], preferring the transparent hydrogel Carbopol to the granular gelatin [

17]. The subsequent high-temperature curing of the constructs allowed us not only to create the desired objects, but also to reduce the curing time of the CPC from several days to less than an hour.

Thus, the models which were printed directly on a glass slide were cured using two methods: either by maintenance in a tissue culture incubator as recommended by the provider, or by baking in an electric oven submerged in Carbopol. The Carbopol hydrogel was prepared by slowly adding 1 g of Carbopol 980 NF polymer (Lubrizol, Wickliffe, OH, USA) to 100 mL of distilled water under continuous mixing. Sodium hydroxide (Fisher Chemical, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) was slowly added to the mixture under stirring until a neutral pH was achieved. The gel pH was measured using Whatman indicator strips in the range 4.5–10 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The gel was then put into two 50 mL centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 751× g (2000 RPM) using the Sorvall Legend X1R centrifuge (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 20 min, or until air bubbles within the gel were no longer visible.

For incubation, the constructs were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for five days in a HERAcell 150i CO2 incubator (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The stapes model only re-quired three days to be fully solidified via this method due to its smaller volume as compared to the malleus and incus models. Alternatively, we devised a quicker curing method by use of the myBlock 2B Dual Chamber, 115 V electric oven (Benchmark Scientific, Sayreville, NJ, USA). The blocks of the oven were removed so that the constructs could be placed flat in the oven with the lid closed. A small volume of Carbopol was applied over the printed models, and the constructs were placed in the electric oven at 75 °C for 15–30 min. Thereafter, the prints were hardened enough to be safely manipulated and extracted with a forceps. The remaining dried gel was removed by application of the Gibco 10× HBSS solution (Thermo Fischer Scientific), followed by a brief rehydration and a gentle washing with distilled water to achieve a final anatomically correct model. The models printed directly in a supporting Carbopol bath were also cured in the electric oven for 30–45 min.

To assemble the constructs printed in halves, we used either the Loctite® cyanoacrylate superglue (Hisco, Huston, TX, USA) or, with equal efficacy, the Carbopol gel which was dehydrated between the halves. When using Carbopol to attach the halves, a small volume was applied between the two halves, and the construct was placed in the electric oven at 75 °C for approximately 10 min of dehydration. This attachment could also be reversed by rehydration of the construct. Selected constructs were weighted using a precision balance (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. MicroCT Analysis of 3D Printed Porous Ceramic Models

To prevent brittle fracturing of the porous ceramic ossicle model details, which were rather fragile due to the small anatomical model size, a solution of 4% wt/vol alginate (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied with a pipette on the models’ top, following the contours of the prints, before removing them from the glass support. To allow for the complete diffusion of alginate into the pores of the constructs, these were left to soak in this solution for 30 min. The gel was then crosslinked with either 10% wt/vol CaCl

2 or BaCl

2. BaCl

2 was preferred for microCT scanning, due to the increased contrast in x-ray imaging [

18]; however, only CaCl

2 will be considered for in vitro implantation due to the possible BaCl

2 cytotoxicity [

19]. The crosslinking solution was applied over the gel for 30 min to allow for the full crosslinking of the hydrogel. To keep the hydrogel hydrated after crosslinking, the models were stored in distilled water until scanning.

The porous, gel-infused ossicle models were then analyzed by Micro CT using the Skyscan 1176 (Accela, San Ramon, CA, USA). The samples were scanned at 2000 × 1336 pixels, with an AL 0.5 mm filter and a 0.80° rotation angle. The scans were reconstructed and analyzed using software provided with the Skyscan system (Bruker, Billercia, MA, USA) consisting of NRecon v1.7.4.6, DataViewer v1.5.6.2, and CTVox v3.3.0.0. Model reconstruction was performed using NRecon software with smoothing enabled (level 2), ring artifact reduction enabled (level 8), beam-hardening correction enabled (30%), and a Gaussian smoothing kernel. The reconstructed scans were analyzed using DataViewer software to inspect virtual cross sections of the models. Using color visualization of grayscale threshold, the distribution of crosslinked gel within the model could be visualized. 3D reconstructions were also generated using CTVox software for further visual observation of the printed model and gel distribution.

To determine the pore size distribution, 12 central pores were selected and measured by ImageJ software v1.8.0 (

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html; accessed on 1 February 2022). The scale of the image was set by use of a provided scale bar from DataViewer images. A rectangular measuring tool was utilized to record the estimated height and width of each selected pore. These values were averaged, and the standard deviation was calculated to determine the average size and variance of the pores.

2.5. 3D Printing of Ossicle Models with Bioinks

The alginate models were printed using a 7.5% wt/vol alginate solution in Carbopol as the support hydrogel [

17]. A 0.25 mm ID metal needle tip (REGENHU), 12.7 mm-long, was utilized using extrusion bioprinting. The models were printed using these BIOCAM material settings: needle diameter 0.25 mm, feed rate of 8 mm/s, infill density of 80%, overlapping perimeter of 100%, layer height of 0.25 mm, strand width of 0.25 mm, and velocity of 0.0300 mm/s. The print volume of the ossicle model was 0.2 mL.

Ossicle models were also printed with an alginate-nanocellulose bioink (Cellink, San Carlos, CA, USA) loaded with human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC, from RoosterBio, Frederick, MD, USA). To this end, after trypsinization, the MSC were washed once with alpha-MEM plus 1% serum in a 5 mL Eppendorf centrifuge tube, then the pellet was collected and re-centrifuged in a sterile test tube to obtain a final concentrated (‘dry’) pellet. For printing, the bioink was prepared as nine parts of hydrogel plus one of part cell pellet, to obtain a concentration of 106 cells/mL. Then, the hydrogel models were maintained in the tissue culture incubator for visual observation and imaging.

3. Results

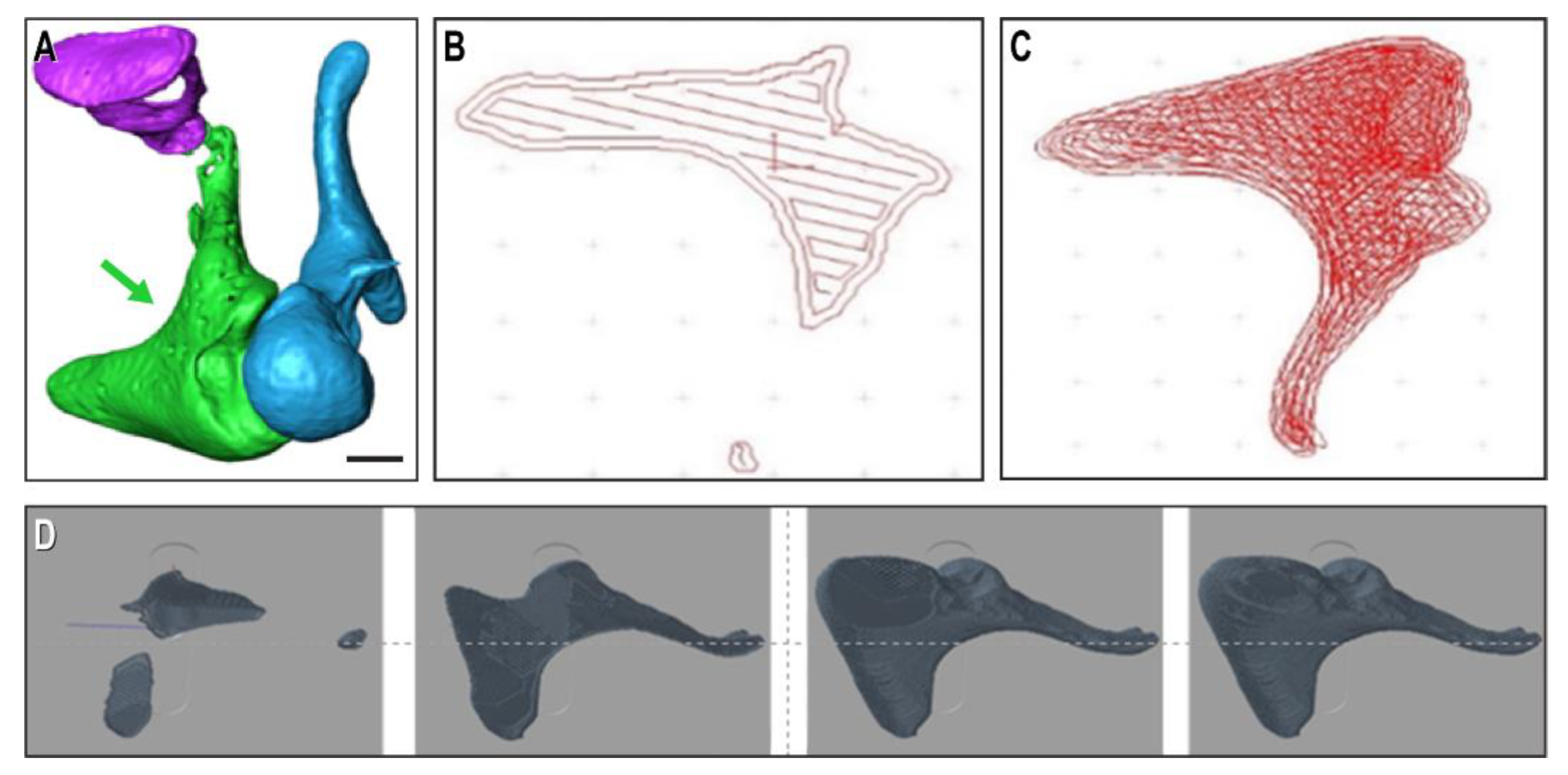

We extracted virtual models of human ossicles from a high-quality open-source database of animal ossicle chains (

Figure 1A), which was imported in the bioprinter’s BioCAD program. The printable files are shown here at single-layer level (

Figure 1B), layer-filling trajectory (

Figure 1C), and as the progression of several layers on top of each other (

Figure 1D) of an incus print.

For printing, we first used the plottable CPC of calcium phosphate/hydroxyapatite paste. Initially, a flat base was required to support this soft material, which was obtained by omitting the bottom layers of the constructs. In this way, we printed in triplicate the malleus and incus on glass slides, showing that the constructs retained the desired structure and external texture (

Figure 2A). The models were cured by heating at 37 °C in 100% humidity for five days for hardening, as recommended by the CPC provider. Due to this treatment, the material became solid, with no discernible changes in structure or exterior texture of the printed ossicle models (

Figure 2B). The stapes was the most challenging to print, as it is the smallest of the three ossicles. For this reason, the stapes model was also made flat on the bottom and printed directly on a glass plate (

Figure 2C). Despite its small size, all four anatomical characteristics of the stapes still appeared visible: the head, anterior crus, posterior crus, and footplate. Due to the small volume of material, the stapes model only required three days of curing at 37 °C in 100% humidity. The model was then strong enough to be removed from the support without fracturing. Additionally, there were no discernable changes to the surface exterior after curing (

Figure 2D).

To test the reproducibility of the procedure with this material, we printed 10 incus models and solidified them as before, then assessed their size both by visual inspection and by mass. We found the models to be reproducible, although minor differences in the external texture could be occasionally observed, and with a relative standard variation of the weight within 6% (

Table S1).

To generate whole constructs by direct printing on a substrate, the CADs of incus and malleus were split in two, and the individual halves were printed facedown directly on a glass plate (

Figure 3A,B). The prints were cured under the same conditions as previously described and assembled by adhesion with a superglue, re-forming the full ossicle models (

Figure 3C,D).

As a more straightforward way to generate whole ossicle models, we also printed the models by an ‘embedding’ method using Carbopol as the supporting hydrogel [

17]. The shape of the printed objects was properly maintained within the Carbopol hydrogel bath, with the additional advantage of easy visual monitoring during and after printing due to its robustness and transparency. The objects were printed within the wells of a 12-well plate (

Figure 4A) and also in a gel support directly placed on a glass slide for high-temperature curing (

Figure 4B). This method allowed the easier extraction and solidification of the models as well (

Figure 4C). The models printed directly on a glass plate could also be cured by using Carbopol to achieve their quicker solidification. To this end, the prints were covered with Carbopol, then placed in an electric oven at 70 °C, allowing the extraction of the hardened models within 15 to 30 min. However, it was observed that models cured in Carbopol on a glass slide may have a rougher surface as compared to models cured for longer in the tissue culture incubator.

Next, we also sought to impart porosity to the 3D printed models, given the subsequent intended in vitro colonization with osteogenic cells, which would benefit from the presence within the implants of a hydrogel containing growth factors. Moreover, the implementation in the construct of a microvascular network within pre-designed channels could be essential for the long-term in vivo success of these implants [

20]. To this end, we developed a porous incus model based on the halved incus design (

Figure 5A) containing large pores derived from an infilling design with more distantly spaced CPC lines (

Figure 5B). The printed model exhibited visible porosity (

Figure 5C), but the constructs expectedly lacked mechanical robustness: in fact, the porous prints that we attempted to remove from the glass support lost some of the surface details because of fracture (

Figures S1A and S2A).

To prevent this brittle fracture, alginate was directly applied over the model after curing before removing it from the glass plate, and the gel was subsequently crosslinked. Although this is not intended to be done in actual in vivo situations, it allowed for the removal without fracture of the model from the glass plate, as well as for the construct manipulation. Excess alginate gel was then removed with a blade, cutting around the porous structure, to retrieve a final porous ceramic gel model (

Figure 5D). This hybrid structure has the potential to act as a scaffold for cells that may be loaded into the alginate hydrogel.

The porous models were inspected under 4× magnification, which revealed an accurate grid pattern achieved by the REGENHU bioprinter (

Figure S1B,C). Alternative porosification options were explored by including in the two-halve incus model several manually designed macroscopic pores (

Figure S1D,E).

Additionally, the pore size distribution of a porous model was analyzed by measuring 12 distinct pores of a coronal cross section reconstruction (

Figure S2B,C). Using ImageJ, the average edge of the rectangular pores was estimated to be 0.259 ± 0.040 mm (

Table S2). We also generated 3D models of the scanned objects by using CTVox software without an alginate coating (

Figure S2D) and with a 6% alginate coating, helping the visualization by microCT of the hydrogel around the model (

Figure S2E). This was consistent with the observation that the brittle porous models could be handled without fracture by containing the model within the crosslinked hydrogel.

We used microCT scanning to further analyze the distribution of alginate within the pores of the scaffold. The porous models were initially soaked within 6% wt/vol alginate (

Figure S2A); however, the microCT analysis revealed that the gel did not completely penetrate the pores of the scaffold within the time aliquoted, perhaps due to the density of the alginate solution. For this reason, we also exposed the incus models to 4% wt/vol alginate and then crosslinked it with CaCl

2. The porous incus top-half model was then scanned via the Skyscan1176 (

Figure 6A) and reconstructed via the NRecon program. Using Dataviewer software, color filters were applied to virtual cross sections of the model to visualize the hydrogel and the CPC structure (

Figure 6B). To determine if the alginate was distributed through the pores, a transaxial cross section was taken in the body of the incus (

Figure 6C). A different color filter was applied to the cross section to visualize the hydrogel and the printed construct, revealing alginate within the pores of the constructs, not only on the surface (

Figure 6D).

The two larger ossicle models were also printed in the Carbopol support bath either with alginate alone (

Figure 7A) or with an MSC-containing alginate–nanocellulose bioink (

Figure 7B). MSC were used as they have been shown capable to undergo in vitro chondrogenic [

21] and osteogenic differentiation [

22]. In both cases, we obtained an excellent rendering of the ossicle’s shapes, as encoded by their CAD (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

Extrusion bioprinting, or the generation of 3D structures from cells and/or biomaterials through layer-by-layer deposition, is emerging as a powerful new technology of tissue engineering [

23]. So far, the applications of 3D printing to the human auditory chain have been prudently considered mostly for modeling purposes [

24]. However, the biofabrication of such individualized medical implants is suitable for an additive manufacturing approach, due to the irregular (anatomic) shape and variable dimensions of the ossicles, as well as to the lower costs of this technique (compared to those of other methods). In spite of its anticipated usefulness [

7], currently there is no established procedure for making ossicles from biomaterials and/or cells.

Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility of using bioprinting to create anatomically realistic human ossicles models. We also sought to ‘push the envelope’ towards the creation of more realistic details with this technology, by testing the available design and implementation options using biomaterials likely to be of value for such next-generation personalized biological implants.

The challenge of creating bone-like ossicle constructs consists in finding the best combination of design, printing methods, and materials. Accurate 3D models of the malleus, incus, and stapes have been previously created from CT scans [

25]. These models were modified for patient-specific anatomy using high-resolution 3D image reconstitution by micro-grinding and by computer-assisted redesign [

20]. Models could be directly obtained from microCT scans of the actual patient’s middle ear and designed from scratch. However, since this process is time-consuming and expensive, a better alternative might be to first determine the patient’s ossicles size and shape and then edit a pre-existing CAD model accordingly. This could be particularly useful for cases of bone degeneration leading to age-related hearing loss.

Our studyis among the first examples of 3D printing of a ceramic paste by a gel-suspending method [

16], adapted for the use of the transparent medium Carbopol [

26]. To solidify the CPC constructs thus made for extraction, we tested both the provider-recommended long-term incubation at 37 °C at a saturating humidity (followed by high-salt solution washing) and an original, expedited curing at 70 °C in room atmosphere (followed by water sprinkling for re-hydration).

We also compared the constructs printed in the supporting gel Carbopol with those of half-models made by printing directly on glass slides, followed by solidification and adhesion. The former approach is more straightforward, and the constructs were more robust than those obtained by the bonding of the halves (which also often left behind imperfectly matched edges); however, the former approach was more prone than the latter to losing smaller surface details. The ‘superglue’ method could be preferable for implantation purposes, since it would hold the model together more firmly than the dehydrated Carbopol, which may rehydrate once implanted. The superglue for mounting together the two halves of the constructs was based on cyanoacrylate, but other options may be considered. In this regard, it is useful to note that cyanoacrylates have become widely used in intra- and extraoral surgical procedures [

27], based on their safety, efficacy, and ease of application [

28], in spite of earlier findings of cytotoxicity in certain tissues [

29]. Moreover, new formulations of these material are being continuously investigated [

30].

The Carbopol-embedded printing approach was also instrumental for creating ossicle models with alginate-based bioinks, alone or loaded with MSC, the cells being able to undergo osteogenic differentiation via chondrocytes [

21] (given the endochondral nature of ossicles’ embryogenesis [

31]) either upon in vitro cultivation or directly when bioprinted in the alginate hydrogel [

22]. This finding also argues for the good cell-supporting properties of calcium-crosslinked alginate, including the maintenance of viability for the time needed by the cells to differentiate in an osteogenic medium [

22]. In vitro, the degradation of alginate varies, depending on its crosslinking [

22] and molecular composition, between two [

22] and four [

32] weeks, i.e., long enough to support the osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of MSC, respectively.

Considering that the solid ceramic implants are brittle and when tested in the clinic had a high failure rate [

5], we integrated the ceramic models with a hydrogel, as a biological material with viscoelastic properties to counteract the brittle nature of the ceramic materials. The penetration of a ceramic construct with large-enough pores by a hydrogel in vitro and/or by cells in vivo, although not immediately providing a mechanical benefit (or on the contrary), may actually lead in the long term to a better accommodation of the model to the surrounding tissues. For this reason, we also tested the printing with CPC of models with pores in the hundreds-of-microns range, by using a CAD-generated print toolpath.

These porous models could be printed in a meaningful size; however, all the anatomical shape details could not be retained through this method yet. This limitation was mainly due to the fragility and brittleness of these tiny porous models, which made small anatomical details prone to breaking during solidification and manipulation. To aid in the handling of the small and fragile porous models, the models were coated with crosslinked alginate. This result suggests that alginate embedding may improve the mechanical properties of these fragile constructs and temporarily prevent their brittle fracture until they are further solidified via in vitro ossification by the scaffold-colonizing cells. Moreover, the incorporation of the porous ceramic in the alginate solution followed by physical crosslinking with either CaCl

2 or BaCl

2 also facilitated the microCT analysis of the constructs. This was due to the high atomic mass of calcium and barium, which increased the hydrogel’s contrast [

18], making it visible simultaneously with the solid ceramic scaffold. This is another original contribution of this paper to the field of biofabrication.

Among the other limitations of this study is the lack of exploration of the physical properties of the printed objects as well as of the cultivation of cell-containing ossicle models for osteogenic differentiation. The majority of our work was conducted based on visual observations, seeking to attain both a good model reproducibility in shape and size and an acceptable printing resolution. Admittedly, the resolution of the printing for these models remains a challenge, due to the small size of the ossicles. However, the shape of the constructs may even not need to be strictly similar to their CAD, as shown by others, who needed to slightly adjust the shape of 3D printed implants to accommodate the patient’s ear, even when the CAD was made based on a specific individual’s CT-scan [

25].

In the next phase of our research, we will cultivate in the long term the cell-containing ossicle models, both with and without a CPC porous scaffold, for in vitro osteogenic differentiation. By monitoring the time-dependent changes in the construct dimensions, we will seek to determine the optimal initial cell density and the proportion of porous ceramic needed to adequately maintain the initial shape of the ossicles’ soft component.

Although the viability and proliferation of the cells contained in the alginate–nanocellulose constructs were not analyzed in this study, in the next phase of our research, we plan to perform a long-term cultivation of cell-containing ossicle models, both with and without a CPC porous scaffold, to evaluate their in vitro osteogenic differentiation. For models printed without CPC scaffolds, custom alginate hydrogel formulations may be explored to induce bone differentiation. It has been suggested that the addition of a stiff polymer to alginate bioinks such as hydroxyapatite [

33], polycaprolactone [

34], or poloxamer [

35] may increase the resolution and promote MSC differentiation to osteocytes [

36]. For models with porous CPC scaffolds, we plan to monitor the time-dependent changes in the construct dimensions to determine the optimal initial cell density and the proportion of porous ceramic needed to provide the adequate maintenance to the initial shape of the ossicles’ soft component.

In conclusion, here we demonstrated the capability of 3D printing to create ossicle models from various biocompatible materials and hydrogels, which opens the way towards the generation of anatomically inspired, personalized middle ear prostheses for implantation.