Abstract

This research article examines the impact of economic, health, environmental, and social-economic factors on diverse forms of pro-environmental consumption: energy conservation, water conservation, and recycling. Primary data concerning these variables were collected from 430 individuals using a structured questionnaire following the cluster sampling methodology. Results indicate that one unit increase in environmental, economic, and health concerns improve pro-environment behavior by 52, 64, and 25 units, respectively. In contrast, a 1 unit increase in income deteriorates pro-environment behavior by 0.01 units. Education, age, gender, and owning a home have an insignificant impact on pro-environmental habits. The model explains a 52% variation in pro-environmental habits. The study recommends that effective electronic and social media campaigns increase environmental, economic, and health concerns and improve green behavior. More courses on environmental sustainability in schools and universities can effectively increase ecological knowledge and concerns.

1. Introduction

Human behavior is at the root of most environmental issues we face today. A significant change in how we conduct ourselves across all levels of society, from individuals to leaders, is needed to meet sustainability goals and ensure an environmentally healthy environment for the people living on Earth [1]. Pro-environmental sentiment appears to be growing by the day, with recent polls showing that more than 60% of people worldwide now acknowledge climate change as a severe threat to humanity [2]. However, there has been no discernible trend toward more sustainable lifestyles. People resist change due to various harmful ecological practices and are enslaved by powerful habits that constantly override the latest information and plans [3]. It is not only the choices we make now that form the fundamental base of our unsustainable behavior but also the choices that we took in the past that is become ingrained in our strong habits and lifestyles [3,4,5].

The environmental problems of Pakistan are mainly linked to the poor handling of limited environmental resources. Pakistan is exposed to waste management problems, environmental pollution, and is vulnerable to environmental calamities [4]. Like other developed and developing nations, Pakistan also attained economic growth at the cost of environmental losses, and it is among those nations that are most vulnerable to environmental changes. Agriculture, biodiversity, and civic facilities are the most affected areas. According to Eckstein et al. [5], Pakistan ranks fifth in the ranking of countries most at risk of climate change. The ongoing industrialization, urbanization, and transportation models are responsible for these environmental calamities. However, the pro-environmental behavior that underpins all these activities has not been studied extensively in Pakistan. Despite the mounting global evidence of an association between pro-environmental habits and the wastage of environmental resources, policymakers have paid little attention to it.

There are studies around the globe investigating the determinants of pro-environmental habits and exploring the socioeconomic, cultural, and demographic factors contributing to pro-environmental habits [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Most of the above studies have been carried out in high- or middle-income countries. Meanwhile, in the case of Pakistan, hardly any comprehensive surveys that encompass the socioeconomic determinants of pro-environmental habits are available. In recent years, studies such as Fatima and Azhar [15]; Nisar, Khan, and Khan [16]; and Ahmad et al. [17] examined the pro-environmental behaviors of firms and their determinants in different sectors of the economy. While Saleem et al. [18] and Moon et al. [19] studied the environmental behavior of students and employees in the education sector.

The primary contribution of this research is that it is the first study that focuses on the need for research into the behavioral dimensions of the environment in Pakistan. The complicated environmental problems of Pakistan require people’s participation from the micro to the macro level to curtail the severity of the problem. This is a minimally researched area, as individual actions to protect the environment at the individual level have not yet been studied comprehensively. There is an urgent need for comprehensive research to understand which socio-economic factors influence individual environmental behavior in Pakistan.

Another significant aspect of this research is that it provides an addition to the research in the field of pro-environmental behavior. This understanding can be beneficial in designing policies to encourage environmentally friendly behavior and encourage citizens to be environmentally conscious in Pakistan. The specific objectives of the studies are: (1) to analyze the effect of socioeconomic characteristics on pro-environmental habits; (2) to analyze the effect of environmental concern on pro-environmental habits; (3) to analyze the effect of health concern on pro-environmental habits; and lastly, (4) to analyze the effect of economic concern on pro-environmental habits in Pakistan.

2. Literature Review

Pro-environmental attitude is a strong predictor of pro-environmental behavior, which is supported by the theory of planned behavior [15,20]. Given the relevance of this topic, we conducted a comprehensive literature review of the determinants of pro-environmental behavior. We discovered that despite the diversity of causes, the most prevalent and relevant elements that influence pro-environmental behavior are: (1) socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, (2) environmental concerns, (3) economic concerns, and (4) health concerns [21,22]. We find limited empirical investigations on this issue that provide a fertile ground for additional analysis; moreover, previous research mostly has focused on specific forms of green behavior.

The environmental concern (E.C.) begins from individuals’ biological traits and feelings, information, mentalities, morals, and practices [23]. Environmental concerns can also be attributed to one’s schooling level, age, information, morals, individual standards, and mindfulness about environmental responsibility. A meta-investigation by Bruley et al. [24] revealed that E.C. is one of the chief indicators supporting ecological responsibility. Landry et al. [25] tracked a positive connection between environmental awareness, well-being cognizance, and utilization of environmental resources responsibility. Moreover, Chaudhary [26] announced a positive association between self-evaluated natural responsible and appropriate spending conduct. Environmentalists have frequently warned against the overutilization of natural resources on the planet. E.C. encourages the use of recycled furniture, and garments, and fixing, instead of supplanting, environmental issues [27,28].

These findings predicted that consumers’ apprehensions about the environment would probably decrease the utilization of new items. An undeniable degree of worry about the climate seems to change the everyday extravagant activities of managers [29]. Brieger [30] found that E.C. was among the central points to expanding the awareness and motivation for reusing and recycling. Moreover, worry about wasteful spending gave a more particular route to generate a positive connection between E.C. and reusing and recycling conducted Tam and Chan [31]. Likewise, Armstrong and Stedman [32] found that E.C. increases customer productivity and endorsed ecological practices, such as buying natural items and avoiding items harming others and the climate.

Although existing literature has established a clear relationship between emotions about environmental behavior and willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, it has not focused on the role of ecological concerns in engaging in pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, the current study has formulated the following hypothesis to examine empirically.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is no significant effect of environmental concerns on pro-environmental habits.

Economic concerns are another important determinant of pro-environmental behavior. Economic concerns include the monetary security, price, and value consciousness; thriftiness; and mindfulness of the consumers. The dominance of these concerns in buyers’ decisions play a role in green purchasing [33]. According to Chuang et al. [34], consumers are more motivated by discrete financial worries. Following ecological concerns, the expense of energy is the second most impressive factor for energy saving [35,36].

Likewise, in this survey, Dharmesti et al., concluded that economic concern promotes ecological practices through cautious and careful spending. Aguilera et al. [27] demonstrated that low-pay families have solid impetuses to save spending on rising energy costs. Additionally, the energy utilization of shoppers is considerably associated with the price of petroleum gas, fuel oil, and electricity. Foo et al. [37] concluded that monetary motivation is critical in restricting energy saving. They estimated a positive connection between financial concern and energy-saving conduct. It is natural that financial concerns lead to purchasing recycled items instead of buying new things [38]. Fiorillo and Sapio [39] noted that economic concern is a critical factor of natural behavior toward green purchasing. Therefore, the study formulated the following hypothesis for examination.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is no significant effect of economic concerns on pro-environmental habits.

Health concern is another essential feature of pro-environmental behavior, which reflects well-being-related issues, such as awareness, significance, or stress of those who might be healthy but are nevertheless indirectly affected, such as the families of patients or medical care staff. Climate change is now widely acknowledged as one of the most severe risks to human health today. Overt examples of projected health implications include differences in cold-related mortality, heat, zoonotic diseases, parasitic, infectious, and the consequences of extreme events. Chronic, insidious effects of climate change are not well understood, but they are likely to be significant and increase with time. Moreover, secondary impacts, such as tertiary impacts and restricted freshwater flow, are associated with rising resource conflicts.

According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) newest assessment, climate change is expected to cause around 250,000 more unequally distributed deaths yearly between 2030 and 2050 [40]. However, these values are likely to be underestimated because longer-term secondary and tertiary effects are not considered. As a result, both health experts and the general population are unaware of the problem. As a result, there have been insufficient investments in preparing for the health effects of climate change and a lack of awareness of the critical need for interactive cooperation among the health, behavioral, and environmental sectors.

On the other hand, health effects due to climate change have become more apparent, and this problem is receiving significant attention in the health sector and policy discussions. A few studies have also looked into how well the general public understands the health effects of climate change. This highlights the importance of explaining the health hazards that our unsustainable behavior causes. Climate change has been suggested to be reframed as a public health issue in order to comprehend our reliance on healthy ecosystems better. Even though there are various ecological issues, such as contamination (e.g., water, air, soil), environmental change has become an impressive wellspring of general medical conditions through various illnesses [41]. People who see ecological issues as a genuine danger to their health and well-being have more natural habits, such as reusing, water protection, and buying items harmless to the ecosystem [42]. Apparently, clients with a significant degree of well-being concern are relied upon to have a more grounded empathy for ecological practices. Flores-Ferrer et al. [43] found that well-being mindfulness positively correlated with the support of environmental practices. Furthermore, well-being as an individual aspect has been found to be a driver for the buying of green items [44].

Thus, the literature suggests that buyers with a significant degree of worry about health concerns will purchase more green items. Based on the above discussion, this study formulated the following hypothesis,

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is no significant effect of health concerns on pro-environmental habits.

Sherif et al. [45] defined pro-environmental socioeconomic norms as “recognized or implied standards on how members of a society act and should act.” Likewise, Hadiputro and Handayani [46] found that socioeconomic standards significantly impacted pro-environmental behavior. The existing literature is clear that perceived socioeconomic norms significantly impact pro-environmental behavior. When people perceive less favorable socioeconomic norms, affect is more likely to be related to behavior than when they perceive more accepted norms. When people sense more normative support for a behavior, the norms are more likely to be the driving force behind their actions.

However, when people do not perceive normative support, other factors are more likely to lead to their behavior, such as mood [47]. According to studies, patterns may arise only for certain types of behavior. For example, pro-environmental social norms modify the association between positive affect and fundamental pro-environmental behavior, but not between positive affect and proactive pro-environmental behavior. Social norms are linked to normal behavior, which translates to basic pro-environmental behavior. People who engage in aggressive pro-environmental behavior act unexpectedly or differently to the inferred behavioral requirements of pro-environmental societal norms [44]. In other words, people who perceive more positive pro-environmental socioeconomic standards should display stronger positive connections between socioeconomic characteristics and pro-environmental behavior [48]. As a result of the preceding discussion, this study suggests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There is no significant effect of socioeconomic characteristics on pro-environmental habits.

2.1. Studies about Pakistan

In Pakistan, research studies started to record green behaviors from 2010 onward [49,50,51,52]. These studies found social and environmental concerns and perceptions regarding environmental problems are the main drivers of green behaviors. Recently, Sana Tariq [53] examined the interaction between pro-environmental behavior and corporate social responsibility perceptions in three business schools in Peshawar. Cleanliness, plantation, waste decrease, and energy preservation were taken as pro-environmental aspects of CSR. They found that CSR shaped pro-environmental attitudes through ecological awareness. Moin et al., [19], from a survey of university students, concluded that the perceived seriousness of environmental problems was the main determinant of green behavior.

2.2. Research Gap

The comprehensive literature review reveals a huge contextual and practical gap in the case of the socio-economic determinants of pro-environmental behavior in Pakistan. We require a comprehensive study examining the impact of economic, health, environmental, and socio-economic factors on pro-environmental behavior in Pakistan specifically. In a developing economy, such as Pakistan, which is one of the nations most affected by climate change, a research study determining the contributing factors to responsible ecological behavior is urgently needed.

3. Theoretical Discussion

Moreover, early research on pro-environmental behavior is scant and generally focuses on its determinants. They typically examined the predictive power of one or more determinants but did not encompass a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain why people engage in certain behaviors [54,55]. The development of psychological theories provides references for studies on pro-environmental conduct that take into account an individual’s internal psychological process prior to engaging in the behavior. The theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory is the psychological theory most frequently used to examine pro-environmental behavior [56].

The theory of planned behavior serves as an important theoretical foundation to explain pro-environmental behavior as the successor to the theory of reasoned action. Additionally, it is a popular topic for research [56,57,58]. Scholars have examined the influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control on intentions to engage in pro-environmental activity based on this theoretical framework [59] and confirmed their predictive importance [60].

Additionally, this is a popular topic in various studies [56,57,58]. Scholars have examined the influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control on intentions to engage in pro-environmental activity based on this theoretical framework [59] and confirmed their predictive importance [60]. Researchers tried to broaden their study horizons as pro-environmental behavior research. Based on sociological ideas, some researchers looked at how people behave in favor of the environment, highlighting the importance of social contact, social capital, and other elements [61]. This is very important to find the influential nodes in any big network, such as social me-dia networks to propagate the information in a useful way [62,63]. As a result, social interaction theory has emerged as a critical theoretical framework for understanding how social context shapes pro-environmental behavior. Previous research demonstrated that social interaction gives people valuable information [64], increases their knowledge of environmental issues and protection, and encourages them to engage in environmental protection practices [61].

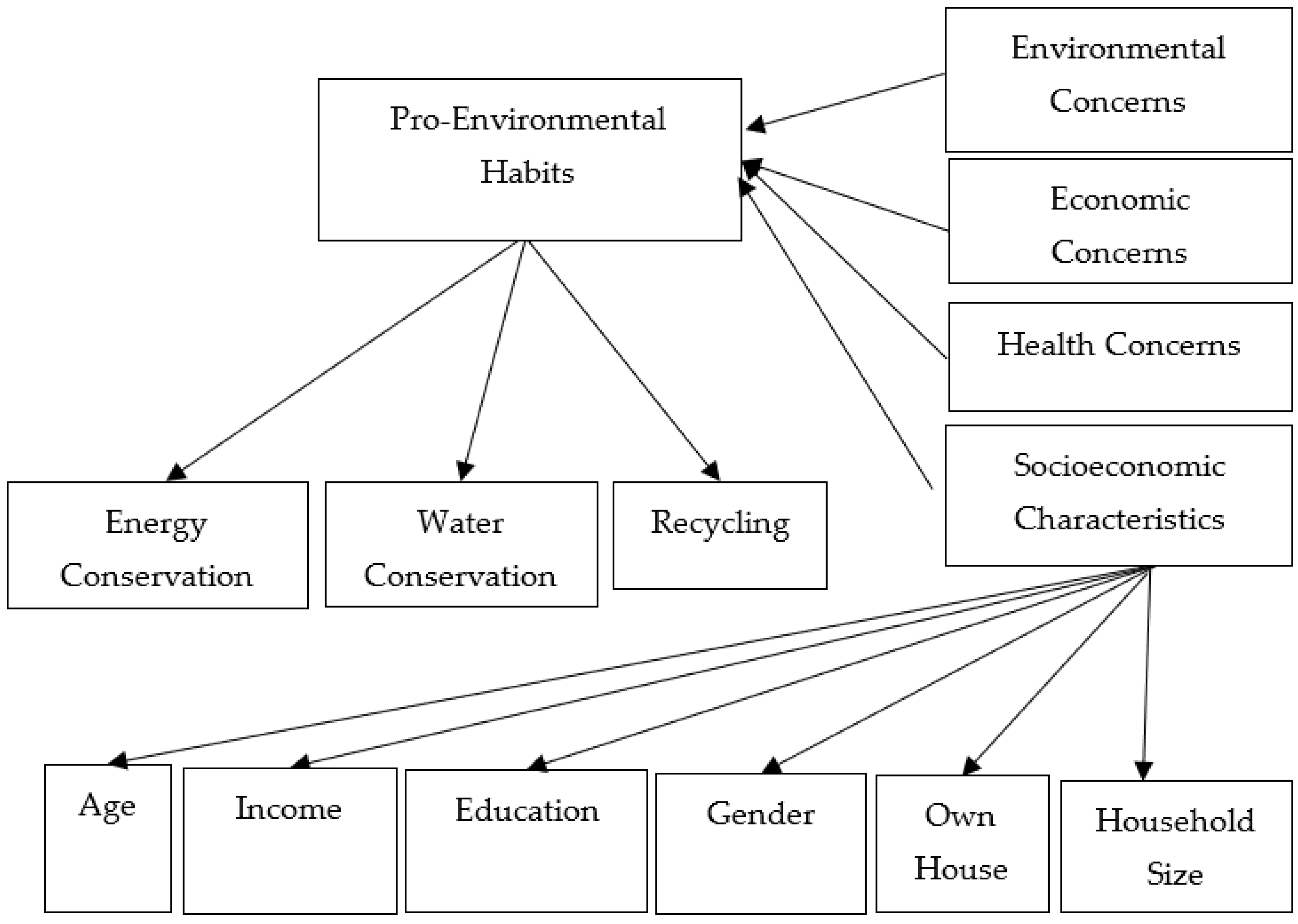

When examining pro-environmental behavior, economists pay greater attention to the influence of external factors, such as price and income, than psychologists and sociologists, which offers a more grounded perspective for research [65]. According to conventional and neoclassical economic theories, people are rational and aim to maximize their utility. According to this line of thought, economic incentives are a powerful tool for encouraging people to practice environmental protection [66]. Rational choice theory is primarily used in pertinent studies to explain the above link [67]. However, experimental data reveal that people frequently stray from the rational choice theory’s claim and are not always rational when making decisions [68]. In this instance, academics have expanded the rational choice model and reexamined the connection between economic incentives and pro-environmental conduct. Based on the above discussion, the current study has developed the research framework as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

4. Methodology

This study analyzes the factors affecting pro-environmental habits in Pakistan. Pro-environmental habit: water and energy conservation and recycling are dependent variables, whereas independent variables are an environmental concern, health concern, economic concern, and socioeconomic characteristics. Primary data concerning these variables were collected from 430 individuals using a structured questionnaire, a method which is known to have the advantages of obtaining data proficiently in terms of cost, time, and energy. The questionnaire consists of five (5) sections overall. Section (A) consists of 19 items geared toward respondents’ pro-environmental habits, such as energy conservation, water conservation, and recycling. Section (B) of the questionnaire is about environmental concerns or education about the environment. Section (C) asked about health concerns and their environmental thoughts. Section (D) raises the question of economic concern, while section (E) gathers information about socioeconomic characteristics, such as income, education, household size, house age, and gender.

The infrastructure developed throughout the Punjab and Sindh province are almost uniform; however, southern Punjab (Bahawalpur and Multan divisions) is considered less developed as compared to the other parts of Punjab. Moreover, the energy and water prices and availability are also almost the same throughout the country as energy prices and availability are regulated by the federal government instead of provincial governments. Therefore, the data related to energy and water usage as well as their prices are almost the same in both provinces.

Based on these facts a multi-stage sample technique has been applied for data collection from both provinces. In the first stage, two provinces in Pakistan, Punjab and Sindh, were selected randomly. In the second stage, two distracts from each province were selected randomly. District Bahawalpur and Multan were selected from Punjab province and District Sukkur and Hyderabad were selected from Sindh province, as shown in Figure 2. In the third and last stage, an almost equal number of individuals residing in urban areas were selected for sample size using convenience sampling. The main reason to use the questionnaires for data collection was to gather more first-hand information through structured interviews. According to Krejcie and Morgan’s methodf [69], when the population size is 1,000,000 and above (or unknown), a sample size of 382 is considered adequate to obtain appropriate representative results. Therefore, the study used a sample of 430 participants through the convenience sampling method because the total population in localities was not precisely known; thus, in this last stage, the non-probability sample is considered more appropriate.

Figure 2.

Study Area.

Econometric Model

The current study employs the following econometric model to analyze the determinants of pro-environmental habits in Pakistan.

where PEH = pro-environmental habits; EC = environmental concern; HC = health concern; ECOC = economic Concern; SEC = socioeconomic characteristics; and µi is the model’s error term (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurements of the variables.

Firstly, the study applied multiple linear regression to analyze the determinants of pro-environmental habits in Pakistan. Meanwhile, as most of the primary data is prone to the problem of heteroscedasticity, White’s test was applied in order to analyze the heteroscedasticity of the data. Based on the finding of White’s test, the study applied generalized least squares (GLS) to the current analysis to estimate the coefficients of explanatory variables as a robustness analysis, because the GLS is assumed to produce efficient and generalizable estimates even in heteroscedasticity. GLS contains ordinary least squares (OLS) as a particular instance, as its name suggests. After A. Aitken, GLS is sometimes known as “Aitken’s estimator” [70]. The possible covariance among independent variables or variances across these observations is the primary reason for choosing the GLS [71].

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Diagnostic Tests

Descriptive statistics aim to check the variations in data and variables. In Table 2, the standard deviation from the mean and the range is the difference between minimum and maximum, indicating widespread dispersion in all measured variables. The missing data can significantly affect the conclusions drawn from the regression analysis. We applied the mean imputation test to find missing values in the data. The results indicate no missing values in the data. A datum that deviates irregularly from the mean value in a population’s random sample is referred to as an outlier. An information point that differs significantly from possible explanations is also known as an outlier in statistics. An outlier may indicate an investigative error or be the result of measurement inconsistencies. In this study, Cook’s D test was applied to detect outliers. The test results show that no outliers exist in the data. The data, therefore, can be used for further processes, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Date cleaning and diagnostic tests.

Furthermore, Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to determine whether a dataset is well-modeled by normal distribution and compute how likely it is for a random variable underlying the dataset to be normally distributed. The findings of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicate that all the variables are normally distributed, as the results are significant at a one percent level of significance. Similar results were observed in the case of the Shapiro–Wilk test, where all the variables are significant at a one percent level of significance. Moreover, the regression analysis on primary data can be prone to the problem of multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity. This problem can make the interpretation and generalization of the coefficients unreliable. We employed the variance inflation factor (VIF) to examine the multicollinearity problem in the regression: “VIF measures the amount of multicollinearity in a set of multiple regression variables”. The value of this test is less than 10, indicating that the problem of multicollinearity is manageable.

However, in our case, VIF is far less than 10, indicating no problem of multicollinearity at all. As the data are free from the problems of normality, outliers, and multicollinearity, we can comfortably apply regression analysis to find the estimates of the determinants of the pro-environmental behavior. Table 2 shows the results of diagnostic tests. Lastly, to avoid the common method bias issue, the principal component analysis was applied to all items used in constructs. According to Wooldridge [73], if the total variance extracted by one factor exceeds 50%, common method bias is present. Meanwhile, there is no problem with common method bias in these data, since the total variance extracted by one factor is less than the recommended threshold of 50%.

5.2. Regression Analysis

The regression results in Table 3 reveal an R-square value of 0.52. This implies that the model explains a 52% variation in pro-environmental habits, while significant F-statistics indicate a good model fit to the data. However, as the cross-section data are mostly prone to the problem of heteroscedasticity, this makes the inference of the results unreliable; therefore, we applied the commonly used White’s test to detect this problem. The test statistics, with a probability value of 0.00, reject the null hypothesis of no heteroskedasticity in the regression model. An alternative hypothesis is therefore accepted, where the regression model has the problem of heteroscedasticity.

Table 3.

Regression analysis.

5.3. Robust Analysis

In the robust analysis, R-squared and Akaike info criterion (AIC) indicates that the model is an excellent fit for the data, as shown in Table 4. The explanatory variable explains substantial variation in the criterion variable: pro-environmental behavior. However, White’s test indicates the heteroscedasticity problem, and we cannot generalize the results shown in Table 5. We, therefore, precede to the generalized least square (GLS) GLS estimation method. The results of GLS are more reliable even in the presence of heteroscedasticity.

Table 4.

Robust statistics.

Table 5.

Heteroscedasticity and White’s test.

5.4. Generalized Least Square (GLS)

This study used the generalized least square (GLS) estimation method to deal with the heteroscedasticity problem. GLS is a technique for assessing the unidentified parameters in a linear regression model when there is a certain degree of correlation between the residuals in a regression model and when the data have the problem of heteroscedasticity. The results of the GLS regression are given in Table 6. The environmental concerns, economic concerns, health concerns, and household size have a significant positive impact, while income significantly negatively affects pro-environmental habits. Education, owning one’s own home, gender, and age have insignificant impacts.

Table 6.

Generalized Least Square (GLS).

These results imply that more economic concern improves pro-environmental habits. Economic concern suggests more correction in spending money and resources on products and services. Several studies, such as [14,74,75], also have comparable findings. Similarly, Abrar ul Haq et al. [76] discovered that a readiness to make economic sacrifices to safeguard the environment had a beneficial impact on the amount of attention devoted to (unspecified) eco-labeled goods, resulting in pro-environmental purchasing intentions.

According to the results of our sample data, if economic concern increased by 1 unit, then the pro-environmental habits will be improved by 64 units measured on the scale of this study. These findings are similar to the results of some earlier studies [14,75,77,78,79]. According to Dube and Casale [80], environmental concern comes from political discourse and refers to “the entire range of ecologically connected perceptions, emotions, knowledge, attitudes, values, and behaviors” (p. 21). Environmental concern was previously described as a broad or specific perception of an environmental problem. The current study’s findings indicate that environmental concerns have a positive and significant impact on pro-environmental habits. If environmental concern increases by one unit, pro-environmental practices will be improved by 52 units. These results align with the findings of Kim et al. [81], Longhi [82], Nguyen et al. [83], and Rajapaksa et al. [7].

Health concerns also have a positive and significant impact on pro-environmental habits. Results indicate that when health concerns increased by 1 unit, then pro-environmental habits also improved by 25 units. Environmental problems are a danger to health; therefore, health-conscious people are inclined to display more pro-environmental behavior, such as recycling, water, energy conservation, and buying eco-friendly goods [84]. Liobikiene [48] found that health awareness positively correlates with pro-environmental behavior. Our findings are similar to those of the existing literature [85,86,87,88].

The income of the individuals has been found to harm their pro-environmental practices. These results align with the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) theory that people move towards a resource-intensive lifestyle as income grows in developing countries. According to the results, if income increases by one unit, pro-environmental habits will deteriorate by 0.01 units. These findings align with Binder et al. [89] and Turnbull et al. [90].

Household size also has a positive and significant association with pro-environmental habits. If the household size increases by 1 unit, then pro-environmental practices also improve by 18 units. Delavari Edalat and Abdi [91] also found a significant and positive relationship between household size and the acceptance of water-saving technologies. These findings align with the results of Delavari Edalat and Abdi [91], White et al. [92], and Zhang et al. [93]. However, in contrast, some literature also advocates that the vertical growth of the houses and cities creates more significant savings of environmental resources than the horizontal expansion of the towns [94]. Meanwhile, education, age, gender, and owning a home had an insignificant impact on our sample’s pro-environmental habits. This implies that we cannot generalize these coefficients.

6. Practical and Theoretical Implications of Findings

Environmental issues are the biggest threats facing humanity in the 21st century. Global warming, climate change, and air and water pollution seriously impact human life. Pakistan is also facing severe environmental problems. Social scientists are researching the human behavioral aspect of environmental issues. In recent years, research concerning how people’s everyday actions can impact the environment and ways to motivate people to adopt environmentally responsible measures has increased. The psychological and social factors of environmental behaviors of individuals have been extensively studied in recent years. The research into environmental behaviors in Pakistan is in its infancy phase.

The key findings of the study that economic, health, and environmental concerns promote green behaviors have significant theoretical and practical implications. Pakistan is among the most populous nations in the world regarding population. The last 15 years have seen a considerable change in Pakistani society. Exposure to social media has increased the impacts of global consumerism. There is a noticeable change in the social structure, especially in urban areas of Pakistan. The consumption of fast food and packaging of food delivered to home has increased. Electronic devices, such as mobile phones, printers, computers, and computers have changed how we think about everyday production and dispose of waste.

Thus: economic concerns—correction in spending money and resources on products and services; environmental concerns—perception of ecological problems; health concerns—health-consciousness can improve the environmental behavior, which is very encouraging. This knowledge can be utilized in design programs and policies encouraging environmentally responsible behavior and promoting ecologically responsible citizenship in Pakistan. Moreover, these findings significantly contribute to the literature, as this is one of the limited studies conducted in a country in its early stage of economic development and where the environment is not the main priority of the people (EKC Theory).

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This study concludes that people’s environmental, economic, and health concerns can significantly improve their pro-environment behavior. Effective electronic and social media campaigns can increase ecological, economic, and health concerns. More courses on environmental sustainability in schools and universities can effectively increase ecological knowledge and concerns. Standard theories on the link between income and the environment suggest that more income in the early stages of economic development leads to a more resource-intensive lifestyle. The findings of this study also confirm this theory. However, if individuals are well informed about the environmental consequences of their consumption, they can move to energy and water-efficient appliances.

Awareness about the environmental impact of our daily activities is exceptionally minimal in Pakistan. At an individual level, the recognition of ecological challenges facing Pakistan and its citizens and the likely challenges that could likely arise in the future is very limited. The national policy on environmental protection of Pakistan recognizes the importance of raising public awareness about environmental concerns at the individual level.

8. Limitations of the Findings and Direction for Future Research

This study had only limited time and finances to conduct a comprehensive survey. The survey errors involve a trade-off with cost. The survey errors can be reduced by increasing the sampling size, interviewer training, and extending monetary incentives to respondents; however, these measures involve cost. Funding agencies should therefore support future work to obtain more comprehensive overviews of behavioral attitudes of the environment in developing countries, such as Pakistan. Moreover, new complex models must be employed to incorporate psychological factors as determinants of pro-environmental behaviors. Future investigations concerning environmental behaviors in the context of developing nations, such as Pakistan, have to scrutinize the nature of the link between diverse social, demographic, and psychological variables as they relate to the ecological behaviors of individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; Methodology, M.A.u.H.; Software, F.A.; Validation, A.R.G.; Formal analysis, M.A.u.H.; Investigation, F.A.; Resources, H.A.M.M.; Data curation, A.A.; Writing—original draft, M.A.u.H. and A.A.; Writing—review & editing, F.A., A.R.G. and H.A.M.M.; Supervision, A.R.G.; Project administration, A.A.; Funding acquisition, H.A.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was not funded by any source (individual, group, or organization).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the current study were extracted from published annual reports of selected companies listed by the Pakistan stock exchange. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Assembly, U.G. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gislason, M.; Kennedy, A.; Witham, S. The Interplay between Social and Ecological Determinants of Mental Health for Children and Youth in the Climate Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, M.; Dreyfuss-Wells, F.; Nair, A.; Pedersen, A.; Prasad, V. Evaluating Conscious Consumption: A Discussion of a Survey Development Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.Y.; Wasim, M.; Sarwar, M.S. Development of Renewable Energy Technologies in rural areas of Pakistan. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 42, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, D.; Künzel, V.; Schäfer, L.; Winges, M. Global Climate Risk Index 2020; Germanwatch: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Palupi, T.; Sawitri, D. The importance of pro-environmental behavior in adolescent. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 16–18 January 2018; Volume 31, p. 09031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksa, D.; Islam, M.; Managi, S. Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Role of Public Perception in Infrastructure and the Social Factors for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawhouser, H.; Cummings, M.; Newbert, S.L. Social Impact Measurement: Current Approaches and Future Directions for Social Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; McNeill, I.M. Increasing pro-environmental behaviors by increasing self-concordance: Testing an intervention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 102, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wen, Y.; Gao, J. What ultimately prevents the pro-environmental behavior? An in-depth and extensive study of the behavioral costs. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 158, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, S.R.; Campos, R.K.; Bergren, N.A.; Camargos, V.N.; Rossi, S.L. Emergence; Microorganisms, O. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Majid, H.A.; Michael, M.S.H. The role of environmental knowledge and mediating effect of pro-environmental attitude towards food waste reduction. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, I.; Kabadayi, E.T.; Koksal, C.G.; Tuger, A.T. Pro-environmental consumption: Is it really all about the environment? J. Manag. Mark. Logist. 2016, 3, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Azhar, S. Examining the Pro-Environmental Behavior of Employees in Private Organizations of Pakistan. Gov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nisar, S.; Khan, N.R.; Khan, M.R. Determinant analysis of employee attitudes toward pro-environmental behavior in textile firms of Pakistan: A serial mediation approach. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 1064–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.; Kamran, H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, M.; Mahmood, F.; Ahmed, F. Transformational Leadership and Pro-Environmental Behavior of Employees: Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivation. J. Manag. Res. 2019, 6, 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, M.A.; Mohel, S.H.; Farooq, A. I green, you green, we all green: Testing the extended environmental theory of planned behavior among the university students of Pakistan. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 58, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-waste recycling behaviour: An integration of recycling habits into the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimin, Z.; Chishti, M.Z. Toward Sustainable Development: Assessing the Effects of Commercial Policies on Consumption and Production-Based Carbon Emissions in Developing Economies. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211061580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Ulhas, K. Working to Reduce Food Waste: Investigating Determinants of Food Waste amongst Taiwanese Workers in Factory Cafeteria Settings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruley, E.; Locatelli, B.; Vendel, F.; Bergeret, A.; Elleaume, N.; Grosinger, J.; Lavorel, S. Historical reconfigurations of a social–ecological system adapting to economic, policy and climate changes in the French Alps. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, N.; Gifford, R.; Milfont, T.; Weeks, A. Learned helplessness moderates the relationship between environmental concern and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, A.; Haakonsson, S.; Martin, M.V.; Salerno, G.L.; Echenique, R.O. Bloom-forming cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in Argentina: A growing health and environmental concern. Limnologica 2018, 69, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Chishti, M.Z.; Alavijeh, N.K.; Tzeremes, P. The roles of technology and Kyoto Protocol in energy transition towards COP26 targets: Evidence from the novel GMM-PVAR approach for G-7 countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 181, 121756. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162522002815?casa_token=tuS0rC6a26kAAAAA:gSdxtCre7lnQXSE3X-qXHuIJDOurT_7Qb7H1v2gDMFPx1-4AsocMJTJTs_iNFUa26aFjqaqrBS4 (accessed on 26 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.; Chishti, M.Z. Will ASEAN countries be a potential choice for the export of pollution intensive goods? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 81308–81320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brieger, S.A. Social Identity and Environmental Concern: The Importance of Contextual Effects. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 828–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W. Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Stedman, R.C. Understanding Local Environmental Concern: The Importance of Place. Rural. Sociol. 2019, 84, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideologies, I.M. Ecology–Main concern for the Christian space of the 21st century? Catholic and orthodox perspectives. J. Study Relig. Ideol. 2020, 19, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, L.-M.; Chen, P.-C.; Chen, Y.-Y. The Determinant Factors of Travelers’ Choices for Pro-Environment Behavioral Intention-Integration Theory of Planned Behavior, Unified Theory of Acceptance, and Use of Technology 2 and Sustainability Values. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.M.; Manata, B. Measurement of Environmental Concern: A Review and Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, M.Z.; Dogan, E. Analyzing the determinants of renewable energy: The moderating role of technology and macroeconomic uncertainty. Energy Environ. 2022, 958305X221137567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.; McCarthy, J.; Bebbington, A. Activating landscape ecology: A governance framework for design-in-science. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen, S.; Iqbal, J.; Chishti, M.Z. Exploring the dynamic effects of shocks in monetary and fiscal policies on the environment of developing economies: Evidence from the CS-ARDL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 45665–45682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, D.; Sapio, A. Energy saving in italy in the late 1990s: Which role for non-monetary motivations? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165, 106386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M.A.; Depledge, M.H. Healthy people with nature in mind. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, A.; Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M. Consumer segmentation based on Stated environmentally-friendly behavior in the food domain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.G.; Raimi, K.T.; Wilson, R.; Arvai, J. Will Millennials save the world? The effect of age and generational differences on environmental concern. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ferrer, A.; Marcou, O.; Waleckx, E.; Dumonteil, E.; Gourbière, S. Evolutionary ecology of Chagas disease; what do we know and what do we need? Evol. Appl. 2018, 11, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Consumers’ Sustainable Purchase Behaviour: Modeling the Impact of Psychological Factors. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, C.W.; Sherif, M.; Nebergall, R.E. Attitude and Attitude Change: The Social Judgment-Involvement Approach; Saunder: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hadiputro, D.; Handayani, Y. Merti Kali: River conservation based on local wisdom. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Language, Education, and Culture (ISoLEC 2021), Online, 31 July–1 August 2021; pp. 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Steinhorst, J.; Schmitt, M. Plastic-Free July: An Experimental Study of Limiting and Promoting Factors in Encouraging a Reduction of Single-Use Plastic Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Shah, I.; Ahmad, K. Factors in environmental advertising influencing consumer’s purchase intention. J. Sci. Res. 2010, 48, 217–226. Available online: https://lahore.comsats.edu.pk/abrc2009/Proceedings/All%20papers/Factors%20in%20environmental%20advertising%20influencing%20consumer%E2%80%99s%20purchase%20intention%20(Habib%20Ahmad).pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Ali, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, I. Determinants of Pakistani consumers’ green purchase behavior: Some insights from a developing country. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 2, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Rahman, M. Consumers perception of green products: A survey of Karachi. J. Indep. Stud. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. Econ. 2011, 9, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akif, S.; Imtiaz, M.; Subhani, M.I.; Hasan, S.A.; Osman, A.; Rudhani, S.W.A. The crux of green marketing: An empirical effusive study. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. (EJSS) 2012, 27, 425–435. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/35688 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Tariq, S.; Yunis, M.; Shoaib, S.; Abdullahed, F. Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviour: Insights from business schools of Peshawar, Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 948059. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9366603/ (accessed on 2 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbuthnot, J. The Roles of Attitudinal and Personality Variables in the Prediction of Environmental Behavior and Knowledge. Environ. Behav. 1977, 9, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, J.; Shore, B.M. Conservation Behavior as the Outcome of Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1975, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, V.; Marique, A.-F.; Udalov, V. A Conceptual Framework to Understand Households’ Energy Consumption. Energies 2019, 12, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Dynamic analysis of international green behavior from the perspective of the mapping knowledge domain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6087–60989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Shi, S. Social interaction and the formation of residents’ low-carbon consumption behaviors: An embeddedness perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.A.M. Analysis of Social Media Complex System using Community Detection Algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2022, 11, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.A.M. Complex network formation and analysis of online social media systems. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2022, 130, 1737–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, M.; Wei, M. Host sincerity and tourist environmentally responsible behavior: The mediating role of tourists’ emotional solidarity with hosts. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gsottbauer, E.; Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Environmental Policy Theory Given Bounded Rationality and Other-regarding Preferences. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 49, 263–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.F.; Kotchen, M.J.; Moore, M.R. Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.H.; Vatn, A. The divisive and disruptive effect of a weight-based waste fee. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. Household energy use: Applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.; Morgan, D. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, A.C. Note on selection from a multivariate normal population. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 1935, 4, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Porter, D.C. Essentials of Econometrics; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.mheducation.com.sg/essentials-of-econometrics-9780073375847-asia (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Azeem, M.; Hassan, M.; Kouser, R. What causes pro-environmental action: Case of business graduates, Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 24, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; CENGAEG Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://economics.ut.ac.ir/documents/3030266/14100645/Jeffrey_M._Wooldridge_Introductory_Econometrics_A_Modern_Approach__2012.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Paramati, S.R.; Sinha, A.; Dogan, E. Article in Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 27, 13546–13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Knoeri, C. Exploring the psychosocial and behavioural determinants of household water conservation and intention. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 36, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.A.U.; Nawaz, M.A.; Akram, F.; Natarajan, V.K. Theoretical Implications of Renewable Energy Using Improved Cooking Stoves for Rural Households. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2020, 10, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthou, S.K.G. The Everyday Challenges of Pro-Environmental Practices. J. Transdiscipl. Environ. Stud. 2013, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, C.; Hernández, B. Self-Efficacy and Intrinsic Motivation Guiding Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, R.M.R.; Howarth, R.B.; Borsuk, M.E. Pro-environmental behavior. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1185, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, G.; Casale, D. Informal sector taxes and equity: Evidence from presumptive taxation in Zimbabwe. Dev. Policy Rev. 2019, 37, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, S.-H.; Hwang, Y. Predictors of Pro-Environmental Behaviors of American and Korean Students. Sci. Commun. 2012, 35, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, S. Individual Pro-Environmental Behaviour in the Household Context; University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER): Colchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Parker, L.; Brennan, L.; Lockrey, S. A consumer definition of eco-friendly packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothitou, M.; Hanna, R.F.; Chalvatzis, K.J. Environmental knowledge, pro-environmental behaviour and energy savings in households: An empirical study. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Herremans, I.M. Board gender diversity and environmental performance: An industries perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1449–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.E.; Civitello, D.J. Re-emphasizing mechanism in the community ecology of disease. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 2376–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. Are pro-environmental consumption choices utility-maximizing? Evidence from subjective well-being data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, M.; Blankenberg, A.-K.; Guardiola, J. Does it have to be a sacrifice? Different notions of the good life, pro-environmental behavior and their heterogeneous impact on well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106448. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, J.W.; Johnston, E.L.; Clark, G.F. Evaluating the social and ecological effectiveness of partially protected marine areas. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edalat, F.D.; Abdi, M.R. Concepts and approaches of main water managements. Int. Ser. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2018, 258, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, L. Consumers’ perceptions, purchase intention, and willingness to pay a premium price for safe vegetables: A case study of Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ye, N.; Zhang, X. The influence of environmental cognition on pro-environmental behavior: The mediating effect of psychological distance. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology, and Social Science (MMETSS 2018), Zhuhai, China, 20–30 September 2018; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).