Abstract

Post-stroke sequelae, spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis are the most common and disabling diseases of upper motor neurons. These diseases cause functional limitations and prevent patients from performing activities of daily living. This review aims to identify the potential of functional electrical stimulation (FES) for locomotor rehabilitation and daily use in upper motor neuron diseases. A systematic search was conducted. For the search strategy, MeSH terms such as “stroke”, “functional electrical stimulus*” and “FES”, “post-stroke”, “multiple sclerosis”, and “spinal cord injury*” were used. Of the 2228 papers from the raw search results, 14 articles were analyzed after inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Only four articles were randomized clinical trials, but with low numbers of participants. RehaMove, Microstim and STIWELL were reported in three independent studies, whereas Odstock was used in four articles. The results of the studies were very heterogeneous, although for lower extremity stimulation (11 out of 14 papers), walking speed was reported only in 6. Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up and Go, Functional Ambulation Category, 6-Minute Walk Test, 10-Meter Walk Test, Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Motricity Index and Action Research Arm Test were reported for functional assessment. For clinical assessment, the Modified Barthel Index, the Rivermead Mobility Index and the Stroke Impact Scale were used. Four studies were spread over 6 months, two investigated the effects of FES during one session, and the other eight were conducted for 3 to 8 weeks. Improvements were reported related to gait speed, functional ambulation, hand agility and range of motion. FES can be considered for large-scale use as a neuroprosthesis in upper neuron motor syndromes, especially in patients with impaired gait patterns. Further research should focus on the duration of the studies and the homogeneity of the reported results and assessment scales, but also on improvements to devices, accessibility and quality of life.

1. Introduction

The initiation and control of voluntary movements in the human body are possible through an extensive neural network in the cortex, cerebral trunk and spinal cord. Upper motor neuron (UMN) lesions cause a characteristic set of clinical symptoms known as UMN syndrome. The most common symptoms may include muscle weakness, spasticity, and clonus. UMN lesions may be caused by stroke, traumatic brain injuries, malignancies, infections, inflammatory disorders, neurodegenerative disorders and metabolic disorders [1,2]. This scoping review aims to identify the benefits and limitations of using functional electrical stimulation in patients with post-stroke, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury, as these diseases are significant causes of disability worldwide [3,4] and require a review like the present one to gather together and present compact conclusions. Thus, medical practitioners and researchers shall be presented different perspectives so as to start new practice methods and trials.

Stroke and SCI have common motor loss manifestations on human body extremities, such as muscle weakness in distal segments. In addition, muscle overactivity can be encountered, altering activities of daily living (ADL) task performance and gait pattern [5]. Following a stroke or other UMN injury, the nervous system takes intrinsic repair actions, modifying neural circuits by suppressing some existing ones and forming new ones; it may also redesign cortical and spinal cord regions. In addition to the restoring blood flow, the neuroplasticity may cause a surprising level of spontaneous recovery in the UMN following post-traumatic events or brain injuries. Rehabilitation training and pharmacological interventions could modify and boost these neuronal processes, especially within the first three months after stroke onset, with significant improvements in neuromotor function [6,7]. The results of previous research suggest that neuroplasticity is more pronounced during the first 3–6 months after stroke. At the same time, in the chronic stage, its intensity decreases over time and with the formation of new patterns [8]. Moreover, individuals who have suffered incomplete spinal cord injuries (SCI) can regain some motor functionality in the 6 months following the incident, determined mainly by neuroplasticity. However, rehabilitation can take several years [9] and new research suggests that the rehabilitation window should be extended to at least one year after the onset of stroke or SCI event [10,11,12]. Although the symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) vary depending on its subtype, patients have neuromotor manifestations similar to those of post-stroke patients or SCI, related to the distal segment of the lower limbs. Therefore, patterns of muscle spasticity of the ankle and foot and dropped foot are usually encountered. Walking is also strained to a considerable extent; as a result, patients depend on walking assistive devices or wheelchairs. The impairment in the functioning of the upper extremities is not as pronounced as in the lower ones; the patient basically preserves motor function of the upper limbs [13,14,15,16]. Unlike post-stroke or SCI conditions, neuroplasticity in MS can manifest adaptively and improve motor motion performance, or manifest a maladaptive pattern, influenced by the localization of various injuries, inflammation, and the progressive nature of the disease. [17]. Therefore, the time-window of intervention from outside the central nervous system, through physiotherapy, is essential for the complete and complex rehabilitation [9]. Furthermore, rehabilitation techniques or devices are usually used in physical recovery to improve motor functions [18].

The beneficial role of physical exercise is well known regarding UMN disorders. However, besides performing physical training, the sensory-motor loss cannot always be fully restored, and recent research suggest that motor imagery of the movement seems to have a crucial role in brain plasticity. Therefore, any tool facilitating human body movement can play an essential role alongside motor imagery in increasing functional locomotor independence [19,20].

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) is used as an adjunct therapy in stroke rehabilitation, but also for SCI patients, used either to assist in the voluntary rehabilitation of motor activity (early stages after stroke or incomplete SCI) or as a neuroprosthesis (when voluntary motor activity can no longer be restored) [21,22,23,24]; it is also an assistive technology with a beneficial effect for patients with MS with leg involvement (presence of leg drop syndrome) [25]. Functional electrostimulation is divided into two categories: assistance FES for the complete replacement of the motor function, and therapy FES. Therapy FES helps rehabilitate patients with central motor neuron damage (stroke, SCI, MS); it also plays a vital role in preventing muscle atrophy and maintaining the health of the muscular system. Assistive FES aims to restore motor function in patients with upper motor neuron syndrome by completely replacing motor signals. Evidence shows that FES uses brain plasticity to restore the ability to perform voluntary movements after spinal cord injury and stroke [26,27].

The parameters used to optimize FES effects are the duration, frequency and amplitude of electrical pulses. These parameters are precisely adjusted according to the patient’s rehabilitation goals. The pulse duration of FES devices is typically between 300 and 600 microseconds, and these variations can have different effects on the targeted muscles. Electrical stimulation with a wide pulse width of 500–1000 microseconds associated with low frequency has been shown to cause additional muscle fatigue compared to a smaler pulse width. The frequency of the pulses varies between 20 and 50 Hz and is adjusted according to the goal pursued; the low frequency is used to achieve muscle contractions at a lower level of force, thus preventing the onset of early muscle fatigue. The intensity of the pulses varies between 0 and 100 mA; an amplitude value is selected according to the patient’s needs and the targeted muscles. The selection of the amplitude interval is influenced by the pattern and the total simulation time [26]. When high-frequency ESF is applied, patients may experience a tingling sensation in addition to slow muscle contraction.

In this view, this scoping review shall underline the effectiveness of FES in the rehabilitation of neurological patients, either as a single therapy or in combination with other therapies. Different stimulation devices and parameter settings will be approached, according to tailored rehabilitation interventions. We also wanted to identify the latest research insights, therefore we conducted a scoping review of FES published over the last five years to provide valuable insight into the current state of research in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search of MEDLINE, PsychINFO, EMBASE, CENTRAL, ISRCTN, and ICTRP databases was carried out. For the search strategy, MeSH terms such as “stroke”, “functional electrical stimul *” and “FES”, “post-stroke”, “multiple sclerosis”, and “spinal cord injur *” were used. The database inquiry was performed in April 2022.

2.2. Selection of Studies

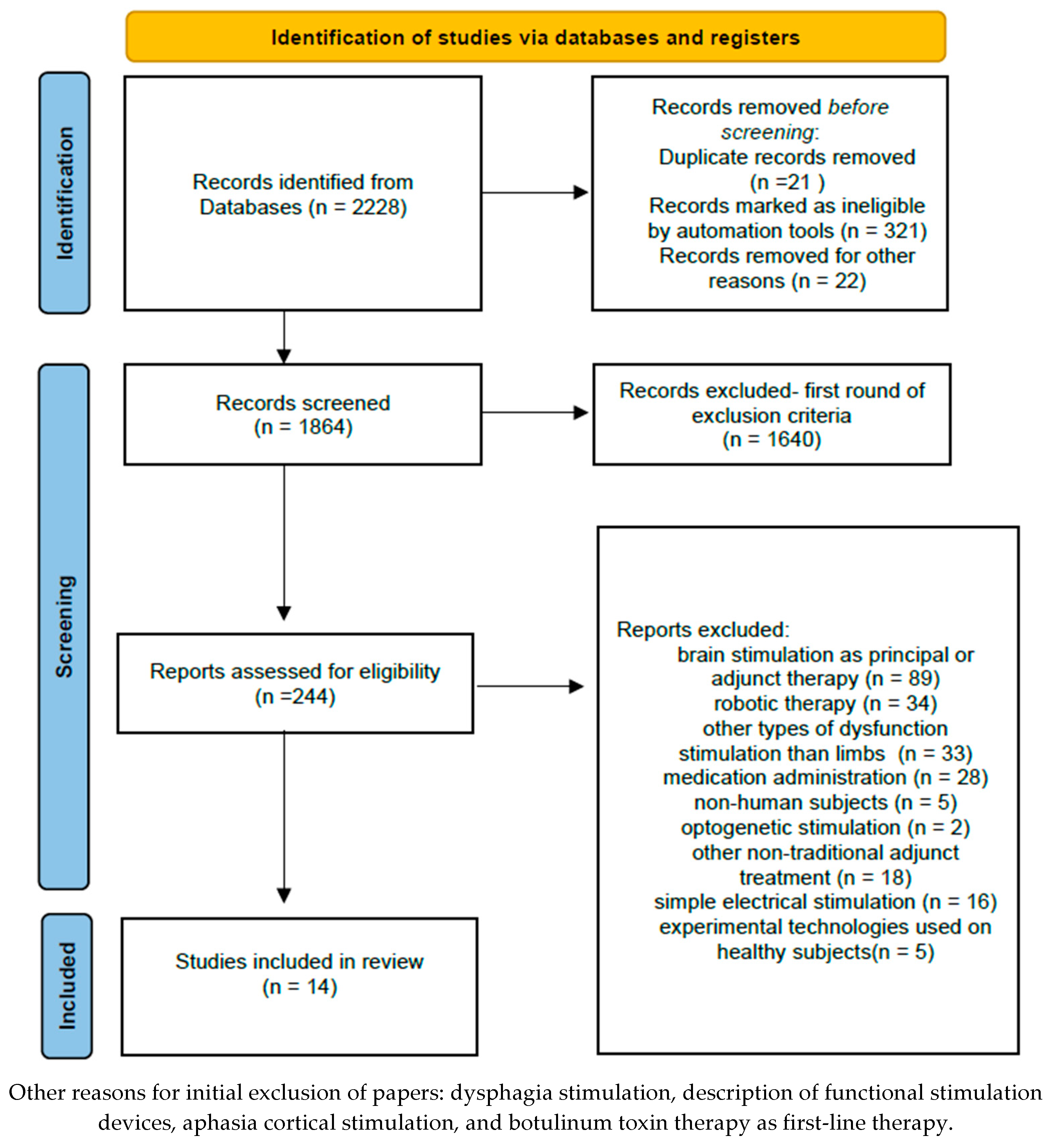

After using the aforementioned keywords, 2288 articles emerged. After applying the first set of inclusion and exclusion criteria (years of publication 2018–2022; article document type; excluding fields unrelated to rehabilitation such as chemistry, electrical engineering, veterinary medicine, dentistry, applied mathematics, psychology, pharmacology, etc.), 244 papers remained.

For secondary processing of the papers, additional inclusion criteria were used: (a) articles were original scientific reports of studies, (b) articles focused on post-stroke, multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injuries diagnosed by using paraclinical methods (e.g., magnetic resonance, functional magnetic resonance, computed tomography), (c) surface FES technology only, (d) articles were published in peer-reviewed journals in English, and (e) articles were available in full-text.

Secondary exclusion criteria included: (a) brain stimulation as a principal or adjunctive therapy, (b) other types of non-limb-dysfunction stimulation (e.g., dysphagia), (c) administration of drugs (e.g., botulinum toxin), (d) non-human subjects, (e) optogenetic stimulation, (f) other non-traditional adjunctive treatment (e.g., stem cells), (g) simple electrical stimulation (without functional training), and (h) new experimental technologies used on healthy subjects.

2.3. Charting Data

First, once the suitable papers were identified, Mendeley Reference Manager was used to gather the articles; it is also a tool which helped easily detect review research elements in every paper.

Therefore, the articles considered eligible for inclusion in the review were identified, and data related to FES application, type of population, and type of study (either randomized clinical trial (RCT) or clinical were extracted by the lead author (NAR) and reviewed by the second author (IVT). Subsequently, data related to the duration of the FES application, parameters used, types of evaluations and results were extracted. All the pieces of information were systematically synthesized by using the data table form in Microsoft Excel.

2.4. Gathering, Outlining and Reporting Results

The data graph organized the information on the research topic by splitting FES use into the three major UMN disorders with locomotor sequelae. The typology of the essential data on the type of population, duration of treatment, devices used, stimulation parameters and outcomes were extracted and structured.

After screening all 244 papers and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14 articles were included in the research. After analyzing them, a critical investigation regarding research methodology, statistical analysis, outcomes and limitations was performed, for a transparent framework on the use of FES. No further statistical analysis could be performed due to the heterogeneity of assessments and outcomes across the studies reviewed.

Accordingly, after reviewing the abstract or the integral texts of the selected papers and applying the exclusion criteria also by using PRISMA flowchart, fourteen studies were considered for review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3. Results

3.1. FES Results on Patients with Post-Stroke Sequelae

The studies carried out on patients who had suffered a stroke included groups of 6 to 48 subjects, as presented in Table 1. The duration of these studies was between 3 and 8 weeks, or even 6 months, depending on the objectives pursued.

In the included studies, 133 participants were reported in the post-stroke category, from which 30 were assigned to the control (post-stroke patients) groups. The left side was affected in 67 patients, and the right side in 66. In the analyzed studies, the time since stroke was very heterogeneous, some considering an onset of 14 days [28] up to an average of 5.8 years [29]. The mean age of the participants was 61.58 years, with a standard deviation of 11.91 (weighted to their count) for six of the seven studies; unfortunately, one study [30] did not report the age or gender of the subjects; the other six studies included 68 men and 45 women.

Table 1.

FES in post-stroke patients.

Table 1.

FES in post-stroke patients.

| Authors | Body Part | Description | Subjects | Intervention | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ha et al. [30] | Lower Extremity/RCT |

|

|

|

|

| Zheng et al. [31] | Lower Extremity/RCT |

|

|

|

|

| Smith et al. [32] | Upper extremity |

|

|

|

|

| Ambrosini et al. [28] | Lower Extremity |

|

|

|

|

| Hakakzade et al. [33] | Lower Extremity |

|

|

|

|

| Tenniglo. J ett al. [29] | Lower Extremity |

|

|

|

|

| Schick et al. [34] | Upper extremity/RCT |

|

|

|

|

FMA = Fugl-Meyer Assessment, PASS = Postural Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients, BBS = Berg Balance Score, BBA = Brunel Balance Assessment, MBI = Modified Barthel Index, TUG = Timed Up and Go, 6MWT = 6-Minute Walk Test, 10 mWT = 10 m Walk Test, FRT = Functional Reach Test, MI = Motricity Index MI, FIM = Functional Independence Measure, FAC = Functional Ambulation Category, BBT = Block and Box Test, WMF–FAS = Wolf Motor Function Test Functional Ability Scale, MAS = Modified Ashworth Scale, RMI = Rivermead Mobility Index RMI, DET = Duncan-Ely Test, AFO = Ankle Foot Orthosis, SIS = Stroke Impact Scale.

3.2. FES in Multiple Sclerosis

In the MS category, 215 subjects were investigated in three studies, as presented in Table 2; with 86 patients in the control groups, including 5 [35] with passive cycling and 81 using ankle foot orthosis [36,37]. In the studies carried out by Jukes et al. [36] and Renfrew et al. [37] there were 78 men and 126 women; the mean age of the participants was 51.68 years with a standard deviation of 11.50 (weighted to their count). Among all the 215 subjects, mean MS diagnosis age was 14.23 years, and the Expanded Disability Status Scale mean score was 5.82. Jukes et al. [36] and Renfrew et al. [37] reported 95 subjects with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, 48 subjects with SPMS, and 39 subjects with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, whereas 21 subjects had an undefined MS subtype.

Table 2.

FES in Multiple Sclerosis.

3.3. FES in Spinal Cord Injuries

The SCI subsection of the analysis included 48 subjects in four studies, plus four subjects with post-stroke sequelae [38], as depicted Table 3. With the exception of Street et al. [39], the acquired data suggest that the spinal lesion was diagnosed with a mean of 7.04 years and the average age of the participants was 36.54 years, with a standard deviation of 11.78 (weighted to their count). Street et al. [39] did not report the genders of the participants nor the cause of SCI. Additionally, the participants’ scores on the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale were not specified; the authors only reported that the analyzed group matched the C and D scores. Furthermore, the study had gaps and missing data regarding the average age of the investigated participants after dropout. In the other three papers, 18 subjects had spinal injuries due to trauma (n = 18), and 6 caused by infection (n = 2), degeneration (n = 2) and tumor (n = 2); 9 participants scored A on the ASIA scale whereas 2 of the participants were evaluated with B, 11 with C, 1 with D and 1 with E [38,40,41].

Table 3.

FES in spinal injury.

4. Discussion

4.1. Current State of the Use of FES in UMN Diseases

The studies in this scoping review report the main findings on the practice and use of FES for the functional rehabilitation of the upper or lower extremities in patients with post-stroke disorders, SCI or MS. Although the analyzed studies were carried out with different devices, on different pathologies, and using various durations of therapy, the review describes the current state of the use of FES in upper motor neuron disease.

Regarding the quality of the analyzed papers (Table 4), two of them do not provide detailed information on the statistical analysis, in particular on the baseline comparison to control groups, sample sizes and effect. If such an in-depth analysis is not carried out, the final results may not be statistically significant. Only six out of the fourteen papers reported the verification of the normality of the data distribution. On the other hand, the other eight articles, even if they used non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon, Mann–Whitney, Friedman), did not specify anything about the normality of the distribution of data. In one study, the power of the sample size and effect size was reported, both a priori and a posteriori [34]. Although in five pieces of research ANOVA was used to identify pre- and post-therapy modifications, none of the authors reported the effect size for every measured parameter. However, partial eta squared can be obtained within ANOVA and provide an effect size of the data.

Table 4.

Quality of reviewed papers.

With regard to the process of blinding in physiotherapy or rehabilitation, it is often challenging to use since many participants may be used to the techniques or procedures of applying electrophysical agents. However, most of the analyzed papers provided sufficient information for the reproducibility of the intervention and the use of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, the therapists can identify the groups by carefully analyzing the patients’ exercise protocols.

A significant obstacle in post-stroke rehabilitation reviews and meta-analysis is linked to the research outcomes. As can be seen in Table 4, for SCI and MS, ASIA and EDSS are used. However, for post-stroke rehabilitation, numerous statistically validated scales with good psychometric properties are available, making the extraction of specific data into a more robust framework or statistical analysis challenging. A higher-qualitative and specific design for more types of post-stroke rehabilitation assessment is needed.

The reliance on FES as a potential tool for lower extremity impairment in UMN injuries was related to gait, primarily to improve gait parameters, as recent research also suggests [36,37]. The recorded results showed improvement in gait parameters, especially in the study where the patients were trained on an FES-assisted cycle ergometer. Additionally, improved balance and decreased spasticity were identified in the FES-assisted training progress in gait parameters [37].

The connection point in the studies carried out on post-stroke patients is represented by the research of gait parameters after the application of FES. The results are promising, with a significant increase in gait speed, but not all the studies use the same types of tests and measurements, and the results cannot be generalized. Another obstacle in data collection and interpretation is the small number of participants.

For the patients with MS and SCI, the duration of FES therapy was longer than for post-stroke patients. Although the sample sizes of patients and the primary disease are different, after six months of use in MS [30] and incomplete SCI [33] for lower extremity dysfunctions, the results of these two studies suggest that FES could be used to improve gait speed by daily use in both MS or incomplete SCI patients.

Recent research on SCI suggests that lumbar and incomplete SCIs have better rehabilitation outcomes than cervical or thoracic injuries, either complete or incomplete [42]. The analyzed papers, although FES was used on A to E grade ASIA impairments, showed that even for a complete SCI, a motor response can be obtained during FES. The therapy parameters used a frequency of 35 to 40 Hz, and a pulse width between 300 and 400 microseconds for the lower extremity was used. The intensity of the FES device was adjusted from 20 mA to 130 mA and to visible contraction [25].

An essential feature of FES in SCI is described in the research carried out by Casabona et al. [41]. Their results show that a 20 min FES therapy session can determine the increase of muscle stiffness, but in 40 min sessions, fatigue appears and negatively influences motor response; therefore, maladaptive feedback seems to manifest in complete SCI patients when FES is overused, somehow depicting a similar response of the upper motor neuron response as in MS [17], with hyperstimulation of the central nervous system or motor deficit units recruiting in a long repetitive task. Moreover, recent research also suggests the need to adjust FES parameters according to muscle fatigue and type of UMN injury, by lowering the frequency of stimuli [35]. Therefore, the duration of an FES session, either as therapy for rehabilitation of normal movement pattern or as neuroprosthesis for UMN locomotor impairments, should be carefully considered in future research, especially in clinical practice. Otherwise, results suggest that clinicians should identify the optimal duration of the FES training session in SCI patients. A limitation of the studies carried out on patients with incomplete SCI is that every study pursues a specific objective (walking speed, grasping ability of the upper extremity, reduction of spasticity); furthermore, there is heterogeneity regarding ASIA scoring in subjects which used FES. Consequently, the evaluation scales and tests are different, the severity of the spine injuries are mixed, and comparison of the results is difficult.

In chronic post-stroke patients, no modification of muscle spasticity was observed during ten therapy sessions of 10 min done over 6 weeks [27]. However, in the research performed on incomplete SCI [29] (eight of ten participants had a C score or higher on ASIA), where 30 min of FES were applied, the results suggested a significant change in hip abductors and knee extensors within four hours after therapy. Recent research on the effects of FES on SCI spasticity suggests that twenty sessions of FES combined with cycling decrease spasticity [38]; therefore, the results of the two studies in our review may be influenced by the FES research and therapy protocol and not by efficacy.

4.2. New Approaches to the Use of FES in UMN Diseases

For the upper extremities, a new system was investigated for the use of FES with biofeedback [43] for 21 post-stroke patients with severe upper extremity impairment, over five weeks, with movement improved with a FES device. However, in a group comparison for moderate upper extremity impairment, no significant difference was found during three weeks of FES and conventional therapy, respectively [27]. Whereas in the research carried out by Hodkin et al. [38] regarding the use of FES for chronic post-stroke and moderate or severe SCI, while the ARAT score improved for both groups, there was a better outcome in the ARAT score for post-stroke patients than for SCI survivors.

The Berg Balance Scale, Time Up and Go, Functional Ambulation Category, 6-Minute Walk Test, 10-Meter Walk Test, Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Motricity Index and Action Research Arm Test were reported for functional assessment. For clinical assessment, the Modified Barthel Index, Rivermead Mobility Index and Stroke Impact Scale were used. Four studies spread over six months, two investigated the effects of FES for one session, and the other eight were carried out for three to eight weeks. The outcomes of the analyzed papers were very heterogeneous, although gait speed was reported in 6 for the lower extremity stimulation (11 out of 14 papers). Further research should focus on the length of the research in time and the homogeneity of the reported outcomes and assessment scales [44].

For post-stroke FES users, the pulse duration was from 250 µs to 475 µs. Four studies used 40 Hz as the primary frequency, whereas one reported 20 Hz, and another, frequencies of 30 Hz and 35 Hz. The intensity used varied from 20 mA to visible contraction. Although FES orthotic devices should not allow skin irritations or injuries, skin erythema was reported in some cases. Nevertheless, we must emphasize that FES should not produce skin injuries if the electrodes are applied without error following the manufacturers’ indications and if FES is performed by medical personnel trained and experienced in electrical stimulation.

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses were performed on post-stroke, spinal cord injury or MS patients and suggested that FES was better than other methods of electrical stimulation (for instance, neuromuscular electrical stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation) for improving motor function of the upper extremities and the abilities to perform ADL in post-stroke patients and spinal cord injuries [26,45]. However, with post-stroke patients, FES combined with cycling needs further research [46].

Although much information regarding the use of FES in UMN disorders suggests patient improvements in ADL and walking, new technologies or strategies of combined therapies are needed. Recent product development research depicts that FES uses necessary adjustments, such as closed-loop operation and real-time feedback, but also emphasizes the ease of access to these devices for UMN-disabled subjects [47].

Among the papers analyzed, only Jukes et al. [36] approaches FES from the point of view of quality of life improvement and cost–benefit analysis for MS patients in a retrospective study; results suggests that although the cost is increased, efficiency and quality of life of MS patients improve compared to standard care. However, information on the costs of FES therapy is not presented in the other reviewed papers, and it represents a major gap in the existing literature and research. Therefore, future studies should also consider cost–benefit analysis in their research.

Although specific studies have investigated the effect of FES together with other rehabilitation methods such as super inductive system therapy, robotic therapy, or direct current transcranial stimulation, which have proven to be effective therapies in motor neuron pathologies [48,49,50], the purpose of this scoping review was to identify the efficiency of FES in addition to physical therapy or functional task training for UMN rehabilitation. Although the analyzed studies are heterogeneous and the evaluation methods are mixed, FES requires improvement in the methodology of clinical trials and guidelines of therapy protocols to prove its significant benefits on the quality of life and the functional independence of patients with central motor neuron diseases. Regarding future perspectives, besides the identification of therapy parameters and protocols, the potential use of FES as a neuroprosthesis, or the potential of a combination of action observation therapy alongside FES to enhance neuroplasticity, should be investigated [51]. The results of this scoping review may be heterogeneous due to the comprehensive nature of the review question, highlighting one of its limitations. In such circumstances, further actions to identify the potential use of FES in CNS disorders may be required as well; and consequently, further studies could be designed from the data based on the present findings.

5. Conclusions

After a stroke, patients with upper central motor neuron injuries, spinal cord injuries or MS can benefit from FES therapy. However, it is necessary to establish a protocol for daily training by identifying therapy parameters and session length, but also identify costs and benefits for the use of this technology as a neuroprosthesis in progressive UMN disorders primarily through the possibility of customization. Future directions should also be considered by identifying the impact on quality of life for UMN disorders and the use of FES, but also investigate the possibility of combining FES with virtual reality training or action observation therapy to enhance brain plasticity and strengthen real-time feedback.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.R. and R.N.; methodology, N.A.R. and C.N.; validation, N.A.R.; formal analysis O.-D.G.; investigation, N.A.R., V.I.T. and O.-D.G.; data curation, N.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.R.; writing—review and editing, N.A.R., C.N. and visualization, V.I.T. and R.N.; supervision, N.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stroke Alliance for Europe. The Burden of Stroke in Europe. 2015. Available online: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/the_burden_of_stroke_in_europe_-_challenges_for_policy_makers.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Yan, L.L.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Miranda, J.J.; Luo, R.; Bettger, J.; Zhu, Y.; Feigin, V.; O’Donnell, M.; Zhao, D.; et al. Prevention, management, and rehabilitation of stroke in low-and middle-income countries. Eneurologicalsci 2016, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.S.; Johnston, S.C. Temporal and geographic trends in the global stroke epidemic. Stroke 2013, 44, S123–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madubuko, A.N. Stroke Risk Factor Knowledge, Attitude, Prevention Practices, and Stroke. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2018. 4973. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/4973 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Aguiar de Sousa, D.; von Martial, R.; Abilleira, S.; Gattringer, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Gallofré, M.; Fazekas, F.; Szikora, I.; Feigin, V.; Caso, V.; et al. Access to and delivery of acute ischaemic stroke treatments: A survey of national scientific societies and stroke experts in 44 European countries. Eur. Stroke J. 2019, 4, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinet, A.S.; Panerai, R.B.; Robinson, T.G. The longitudinal evolution of cerebral blood flow regulation after acute ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 2014, 4, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A.S.; Schwab, M.E. Finding an optimal rehabilitation paradigm after stroke: Enhancing fiber growth and training of the brain at the right moment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.P.; Szaflarski, J.P.; Allendorfer, J.; Hamilton, R.H. Induction of neuroplasticity and recovery in post-stroke aphasia by non-invasive brain stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, B.R.; Maier, M.; Duff, A.; Cameirão, M.; Bermúdez, S.; Duarte, E.; Cuxart, A.; Rodríguez, S.; San Segundo Mozo, R.M.; Verschure, P. A critical time window for recovery extends beyond one-year post-stroke. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclaus, R.S.; Roman, N.; Henter, R.; Caloian, S. Lower Extremity Rehabilitation in Patients with Post-Stroke Sequelae through Virtual Reality Associated with Mirror Therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Long, C.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J. Predicting the Severity of Neurological Impairment Caused by Ischemic Stroke Using Deep Learning Based on Diffusion-Weighted Images. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T.; Kumar, P.; Garate, V.R. A Machine Learning Model for Predicting Sit-to-Stand Trajectories of People with and without Stroke: Towards Adaptive Robotic Assistance. Sensors 2022, 22, 4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Chitsaz, A.; Zolaktaf, V.; Saadatnia, M.; Ghasemi, M.; Nazari, F.; Chitsaz, A.; Suzuki, K.; Nobari, H. Can Early Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Protocol Improve Disability after a Hemiparetic Stroke? A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, E.; Kular, L.; Fernandes, S.J.; Karathanasis, N.; Lagani, V.; Ruhrmann, S.; Tsamardinos, I.; Tegner, J.; Piehl, F.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; et al. Combining evidence from four immune cell types identifies DNA methylation patterns that implicate functionally distinct pathways during Multiple Sclerosis progression. EBioMedicine 2019, 43, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhrmann, S.; Ewing, E.; Piket, E.; Kular, L.; Cetrulo Lorenzi, J.C.; Fernandes, S.J.; Morikawa, H.; Aeinehband, S.; Sayols-Baixeras, S.; Aslibekyan, S.; et al. Hypermethylation of MIR21 in CD4+ T cells from patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis associates with lower miRNA-21 levels and concomitant up-regulation of its target genes. Mult. Scler. 2018, 24, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Küderle, A.; Gaßner, H.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M.; Kluge, F. Inertial sensor-based gait parameters reflect patient-reported fatigue in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučková, B.; Kopal, J.; Řasová, K.; Tintěra, J.; Hlinka, J. Open Access: The Effect of Neurorehabilitation on Multiple Sclerosis-Unlocking the Resting-State fMRI Data. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 662784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nay, K.; Smiles, W.J.; Kaiser, J.; McAloon, L.M.; Loh, K.; Galic, S.; Oakhill, J.S.; Gundlach, A.L.; Scott, J.W. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Beneficial Effects of Exercise on Brain Function and Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Wang, W.; Hou, Z.-G.; Liang, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, W. Enhanced Motor Imagery Based Brain- Computer Interface via FES and VR for Lower Limbs. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.; Kwon, G.H.; Lee, S.; Nam, C.S. Functional Electrical Stimulation Controlled by Motor Imagery Brain-Computer Interface for Rehabilitation. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipp, M.E.; Travis, B.J.; Henry, S.S.; Idzikowski, E.C.; Magnuson, S.A.; Loh, M.Y.; Hellenbrand, D.J.; Hanna, A.S. Differences in neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury in varying animal models and humans. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach Baunsgaard, C.; Vig Nissen, U.; Katrin Brust, A.; Frotzler, A.; Ribeill, C.; Kalke, Y.B.; León, N.; Gómez, B.; Samuelsson, K.; Antepohl, W.; et al. Gait training after spinal cord injury: Safety, feasibility and gait function following 8 weeks of training with the exoskeletons from Ekso Bionics. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Semary, M.M.; Daker, L.I. Influence of percentage of body-weight support on gait in patients with traumatic incomplete spinal cord injury. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2019, 55, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amăricăi, E.; Suciu, O.; Onofrei, R.R.; Miclăuș, R.S.; Iacob, R.E.; Caţan, L.; Popoiu, C.M.; Cerbu, S.; Boia, E. Respiratory function, functional capacity, and physical activity behaviours in children and adolescents with scoliosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060519895093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.D.; Prokopiusova, T.; Jones, R.; Burge, T.; Rasova, K. Functional electrical stimulation for foot drop in people with multiple sclerosis: The relevance and importance of addressing quality of movement. Mult. Scler. 2021, 27, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Qu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, T.; Huang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X. Clinical Benefit of Rehabilitation Training in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine 2021, 46, E398–E410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Xu, H.; Zuo, Y.; Liu, X.; All, A.H. A Review of Functional Electrical Stimulation Treatment in Spinal Cord Injury. Neuromol. Med. 2020, 22, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, E.; Parati, M.; Peri, E.; De Marchis, C.; Nava, C.; Pedrocchi, A.; Ferriero, G.; Ferrante, S. Changes in leg cycling muscle synergies after training augmented by functional electrical stimulation in subacute stroke survivors: A pilot study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenniglo, M.J.B.; Buurke, J.H.; Prinsen, E.C.; Kottink, A.I.R.; Nene, A.V.; Rietman, J.S. Influence of functional electrical stimulation of the hamstrings on knee kinematics in stroke survivors walking with stiff knee gait. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.Y.; Han, J.H.; Ko, Y.J.; Sung, Y.H. Ankle exercise with functional electrical stimulation affects spasticity and balance in stroke patients. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2020, 16, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, D.; Yan, T.; Jin, D.; Zhuang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Wu, W. A Randomized Clinical Trial of a Functional Electrical Stimulation Mimic to Gait Promotes Motor Rehabilitation and Brain Remodeling in Acute Stroke. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 2018, 8923520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Sun, M.; Kenney, L.; Howard, D.; Luckie, H.; Waring, K.; Taylor, P.; Merson, E.; Finn, S.; Cotterill, S. A Three-Site Clinical Feasibility Study of a Flexible Functional Electrical Stimulation System to Support Functional Task Practice for Upper Limb Rehabilitation in People with Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakakzadeh, A.; Shariat, A.; Honarpishe, R.; Moradi, V.; Ghannadi, S.; Sangelaji, B.; Ansari, N.N.; Hasson, S.; Ingle, L. Concurrent impact of bilateral multiple joint functional electrical stimulation and treadmill walking on gait and spasticity in post-stroke survivors: A pilot study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021, 37, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick, T.; Kolm, D.; Leitner, A.; Schober, S.; Steinmetz, M.; Fheodoroff, K. Efficacy of Four-Channel Functional Electrical Stimulation on Moderate Arm Paresis in Subacute Stroke Patients—Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, T.; Motl, R.W.; Pilutti, L.A. Cardiorespiratory demand of acute voluntary cycling with functional electrical stimulation in individuals with multiple sclerosis with severe mobility impairment. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juckes, F.M.; Marceniuk, G.; Seary, C.; Stevenson, V.L. A cohort study of functional electrical stimulation in people with multiple sclerosis demonstrating improvements in quality of life and cost-effectiveness. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller Renfrew, L.; Lord, A.C.; McFadyen, A.K.; Rafferty, D.; Hunter, R.; Bowers, R.; Mattison, P.; Moseley, O.; Paul, L. A comparison of the initial orthotic effects of functional electrical stimulation and ankle-foot orthoses on the speed and oxygen cost of gait in multiple sclerosis. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2018, 5, 5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkin, E.F.; Lei, Y.; Humby, J.; Glover, I.S.; Choudhury, S.; Kumar, H.; Perez, M.A.; Rodgers, H.; Jackson, A. Automated FES for Upper Limb Rehabilitation Following Stroke and Spinal Cord Injury. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, T.; Singleton, C. A clinically meaningful training effect in walking speed using functional electrical stimulation for motor-incomplete spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018, 41, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, A.; Solomon, J.M.; Manikandan, N. Comparison of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and functional electrical stimulation (FES) for spasticity in spinal cord injury–A pilot randomized cross-over trial. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2018, 41, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabona, A.; Valle, M.S.; Dominante, C.; Laudani, L.; Onesta, M.P.; Cioni, M. Effects of Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling of Different Duration on Viscoelastic and Electromyographic Properties of the Knee in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasanizadeh, M.; Yousefifard, M.; Eskian, M.; Lu, Y.; Chalangari, M.; Harrop, J.S.; Jazayeri, S.B.; Seyedpour, S.; Khodaei, B.; Hosseini, M.; et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2019, 30, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Odriozola, A.; Rodríguez-de-Pablo, C.; Zabaleta-Rekondo, H. Hand dexterity rehabilitation using selective functional electrical stimulation in a person with stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e242807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaricai, E.; Onofrei, R.R.; Suciu, O.; Marcauteanu, C.; Stoica, E.T.; Negruțiu, M.L.; David, V.L.; Sinescu, C. Do different dental conditions influence the static plantar pressure and stabilometry in young adults? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.; Fang, Y. Optimal Method of Electrical Stimulation for the Treatment of Upper Limb Dysfunction After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2937–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, E.; Parati, M.; Ferriero, G.; Pedrocchi, A.; Ferrante, S. Does cycling induced by functional electrical stimulation enhance motor rehabilitation in the subacute phase after stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, T.F.; Borges, L.H.B.; Dantas, A.F.O.D.A. Development of an IoT Electrostimulator with Closed-Loop Control. Sensors 2022, 22, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciortea, V.M.; Motoașcă, I.; Borda, I.M.; Ungur, R.A.; Bondor, C.I.; Iliescu, M.G.; Ciubean, A.D.; Lazăr, I.; Bendea, E.; Irsay, L. Effects of High-Intensity Electromagnetic Stimulation on Reducing Upper Limb Spasticity in Post-Stroke Patients. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicketmueller, A.; Rose, G.; Hofmann, M. Feasibility of a Sensor-Based Gait Event Detection Algorithm for Triggering Functional Electrical Stimulation during Robot-Assisted Gait Training. Sensors 2019, 19, 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z.; Kaura, S.; Solanki, D.; Dash, A.; Srivastava, M.V.P.; Lahiri, U.; Dutta, A. Deep Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation of the Dentate Nucleus to Facilitate Standing Balance in Chronic Stroke Survivors—A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Savi, F.; Prestia, A.; Mongardi, A.; Demarchi, D.; Buccino, G. Combining Action Observation Treatment with a Brain–Computer Interface System: Perspectives on Neurorehabilitation. Sensors 2021, 21, 8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).