Featured Application

The method proposed can be used for the identification and control of multivariable nonlinear systems.

Abstract

A novel dynamic inverse control method based on a dynamical neural network (DNN) is proposed for the trajectory tracking control of a flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle (FAHV). Firstly, considering that the accurate model of FAHV is difficult to obtain, the FAHV is regarded as a completely unknown system, and a DNN is designed to identify its nonlinear model. On the basis of Lyapunov’s second law, the weight vectors of the DNN are adaptively updated. Then, a dynamic inverse controller is designed based on the identification model, which avoids the transformation of the nonlinear model of FAHV, thereby simplifying the controller design process. The simulation results verify that the DNN can identify FAHV accurately, and velocity and altitude can track the given reference signal accurately with the proposed dynamic inverse control method. Compared with the back-stepping control method, the proposed method has better tracking accuracy, and the amplitude of the initial control law is smaller.

1. Introduction

Hypersonic Vehicles (HVs) refer to a new type of aircraft flying at a speed of more than Mach 5, which has received widespread attention in the civilian and military fields because of its advantages of global fast arrival and efficient cost [1,2]. The unknown aerodynamic parameters, actuator saturation limitations, and integrated airframe/engine design make the dynamics of the HV uncertain, nonlinear, and strongly coupled, which brings great difficulties to the controller design [3,4,5]. In addition, these unfavourable factors seriously affect the flight performance of HVs and even can lead to system instability.

With the above-mentioned challenges, the design of the guidance and control system for HV has attracted a great deal of attention in the past few years. In terms of trajectory planning, researchers have conducted extensive research on guidance laws under special constraints and made important achievements. In the design of guidance law, the most wide studies are the optimal guidance method. The idea is to transform the design of the guidance law into an optimal control problem and obtain an explicit guidance equation by reasonable assumption and simplification [6,7]. The optimal guidance law method can establish the mathematical model according to different constraint conditions. However, due to the influence of external disturbance, measurement error, and high manoeuvrability of the target in the flight process of HV, there will be a large error in the mathematical model, which can greatly reduce the guidance accuracy [8]. To deal with the disadvantages of optimal guidance, Ref. [9] proposed a search-resampling-optimization (SRO) framework. Numerical simulations demonstrate that the SRO framework is efficient and robust even with narrow accessible tunnels for autonomous dispatch trajectory planning on the flight deck. The SRO is inherently flexible and can be easily extended to the trajectory planning problem for HVs. In addition, Wang et al. [10] proposed a comprehensive investigation of techniques and research progress for the carrier aircraft’s dispatch path planning on the deck, and they provided an exploratory prospect of the knowledge or method learned from other fields. These solutions also can provide some reference for the trajectory planning of HVs.

In terms of trajectory tracking and attitude control, scholars have proposed many control methods for the characteristics of HVs. Considering the constraints of HVs and their complex external disturbances, a predictive control method based on various types of disturbance observers was proposed [11,12,13]. Additionally, considering that sliding mode control is insensitive to parameter variations and external disturbance, sliding mode control for HVs has been extensively studied [14,15,16]. In addition, to improve the anti-interference performance of HVs, reinforcement learning methods [17,18,19] are proposed to estimate various uncertain disturbances of HVs. These methods are conceptually intuitive and improve the robust tracking performance from different aspects, but they are based on the approximate linearization around specified trim conditions or input–output linearization techniques.

However, due to the complex flight environment and unique dynamic characteristics of HVs, accurate models of HVs are difficult or even impossible to obtain. Therefore, in order to expand the practicality of the control methods, the fuzzy logic system [20] and neural network [21,22,23,24,25,26] are proposed to approximate unknown dynamics of HVs. By taking the nonlinear model and external disturbance as an unknown system, a radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) is employed to approximate them [21,22,23]. Moreover, based on RBFNN, Ref [24] takes the FAHV model as an unknown nonaffine system and designs an adaptive neural controller. Additionally, fuzzy wavelet neural network (FWNN) is proposed to estimate the unknown model of HVs to improve the transient performance [25,26]. These methods have been proven to have good control performance, but the adaptive law is related to the control law needed to be designed together with the control law, which will lead to inconvenience in some cases.

The dynamical neural network identifier, proposed by George A. Rovithakis, can not only approximate unknown nonlinear dynamic systems well, but also dynamically adjust weighted parameters independent of control law [27,28]. And it has been applied in DC motors [27,28], unmanned quadrotor formation flight [29], wastewater treatment bioprocess [30], etc. Inspired by this, a dynamic inverse tracking control design method for a FAHV based on DDN is proposed. The main contributions of this paper include the following:

- (1)

- A DNN is used to identify the FAHV model. The weighted parameters of the neural network are updated by the adaptive law and compared with conventional system identification techniques, such as maximum likelihood estimation method [31,32] and Kalman filtering method [33], this approach does not require the exact mathematical model of the object.

- (2)

- Compared with the widely used adaptive neural network control [21,22,23,24], the DNN system identification method adopted in this paper is independent of the control law design, which is convenient for system identification and control law design.

- (3)

- A dynamic inverse controller is designed based on the identification model, which avoids complex model transformations; thus, the controller design process is simplified.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the FAHV model and preliminaries. The neural network identification model and the dynamic inverse controller are developed in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively. Simulation studies are made in Section 5 and the conclusions are presented in Section 6.

2. Problem Description

2.1. FAHV Model Description

The model adopted in this study is developed by Bolender and Doman for the longitudinal dynamics of a FAHV [34]. The nonlinear equations of the longitudinal motion, derived from Lagrange’s equations, including flexible effects by modeling the fuselage as a free beam and the vehicle as a single flexible structure with mass-normalized mode shapes [35], are formulated as

This FAHV model is composed of eleven flight states, i.e., for the five rigid-body states with velocity , flight-path angle (FPA) , altitude , the angle of attack (AOA) , pitch rate , and the flexible modes . Here, and denote the gravitational acceleration and the moment of inertia, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the vehicle mass and the modal frequencies of the flexible structure are different at different fuel levels. It is also seen from Table 1 that the modal frequencies increase as the vehicle mass decreases with the fuel consumption, but, in fact, the vehicle mass decreases on a slower timescale than the velocity and altitude during hypersonic cruise flight [36]. Therefore, nominal values of mass and modal frequencies at the 50% fuel level are considered. While for all flexible modes, the damping ratio is constant, and that is .

Table 1.

Vehicle mass and modal frequencies at different fuel levels.

Besides, the definitions of and that are given by [36,37]:

where .

The correlation coefficients under nominal operating conditions in Equation (2) are

There are three control inputs , , and which are defined as the fuel equivalence ratio, the canard deflection, and the elevator deflection. The canard deflection is ganged with the elevator deflection with a negative gain , i.e., . Therefore, the actual control input that needs to be designed is . Here, , , and denote the reference area, thrust moment arm, and mean aerodynamic chord, respectively. The dynamic pressure is calculated as , where the air density is modeled as with kg/m3 and = 7315.2 m. The meaning of the coefficients and the specific values are referred to [35]. Additionally, from the aerodynamic parameter Formulas (2) and (3) of FAHVs, it can be seen that the various states of FAHVs are highly coupled, and the elastic modes have great influences on its thrust, lift, drag, and pitch moment.

2.2. Model Conversion and Control Objective

The nonlinear dynamic model of FAHV (1) can be written as the following matrix form:

where is the measurable output and z is the controlled output.

Remark 1.

In order to accurately identify all states of the nonlinear system (4), it is assumed that all states of the FAHV system are measurable.

The control objective is to design a control law so that the velocity and the altitude of the FAHV track given reference signals when the motion model of the FAHV is completely unknown.

3. Establishment of Adaptive Identification Model for Flexible Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicle

3.1. Dynamical Neural Network

Dynamical neural networks are recurrent, fully interconnected nets containing dynamical elements in their neurons [27,28]. By dynamically adjusting the weighting coefficients of the neural network, it has been proven that the approximation of a nonlinear function can be achieved with high precision [27,28].

The nonlinear dynamic system of the form (4) can be described by the following system of coupled the first-order differential equation [27,28]

where is an estimation of the state of the FAHV, the input , the output , is a matrix of adjustable synaptic weights, is a diagonal matrix of adjustable synaptic weights, is a diagonal matrix with negative eigenvalues , and is a diagonal matrix with scalar elements , i.e.,

is a 11-dimensional vector with elements of , and is a matrix with elements of . and are represented by sigmoids of the form

where and are constants representing the bound and slope of the sigmoid’s curvature and is a constant that shifts the sigmoid, such that .

3.2. Online Updating for DNN

Assume there exists weight values and such that the system (4) can be approximated by the model

Define the error between (5) and (8) as . Assuming is zero, we obtain

where and which are undated by the adaptive law (15) and (16) derived later.

To obtain the stable updating laws, the Lyapunov second law is used. Considering the following Lyapunov function

where and are positive constant which is referred to as the learning rate of the DNN, and is the ith row vector of matrix and , respectively, i.e. . And because is a diagonal matrix, then .

The derivative of the Lyapunov function is

When Substituted (9) into (11), we obtain

where satisfies the Lyapunov equation .

Since and are scalars, that is

Hence, Equation (12) will be

where .

If , i.e.,

and , i.e.,

is a diagonal matrix,

where is the ith row vector of matrix .

Then,

The above equation illustrates that is negative semidefinite and the identification error is convergent. Using Barbalat’s lemma [38,39], it can be seen that as and .

4. Dynamic Inverse Controller Design Based on the DNN Model

In order to realize the tracking control of FAHV velocity and altitude, a controller is designed based on the DNN model (5).

Assume that the reference signal is , the output tracking error is

Taking time derivative of and using (5), we have

Design the linearizing feedback control law as

where .

Then, substituting (21) into (20), we obtain

Therefore, the error will converge to the origin exponentially.

Remark 2.

To apply the control law (21), we have to assure the existence of .

To analyze the existence of , the learning laws (15) and (17) can be written in matrix form as

where , B, and P are as listed in Equations (6) and (14), respectively.

For our problem, expand matrix , and we have

Since B and are diagonal matrices and , and because the outputs of the FAHV are the velocity and the altitude, we only need to meet the condition and . A projection algorithm was proposed to assure the condition [27,28,40], but it needs to know the optimal value of , and this is difficult to obtain.

As can be seen from (24), to guarantee that is reversible, one can make the elements and equal to zero when generating matrix . Additionally, it is seen from (23) that the condition and can be satisfied by adjusting the parameters and .

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

To illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive identification model and dynamic inverse control, simulation studies were carried out under stochastic constant control and dynamic inverse control. The parameters of the identification model are selected as ,, , , , , , and . The initial velocity and altitude errors of the real system and identification system are taken as 10 and 30, respectively.

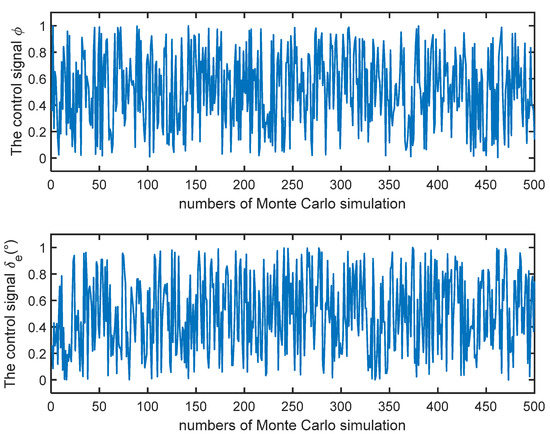

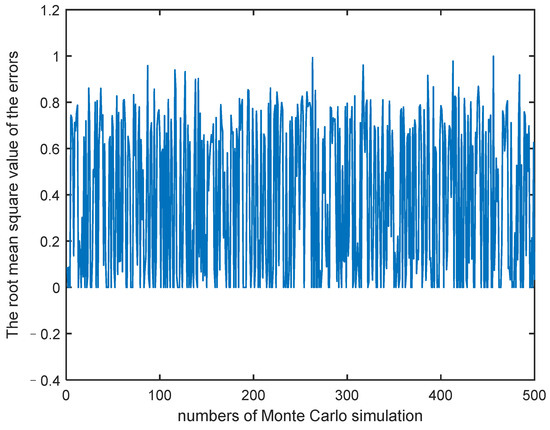

5.1. System Identification under Stochastic Constant Control

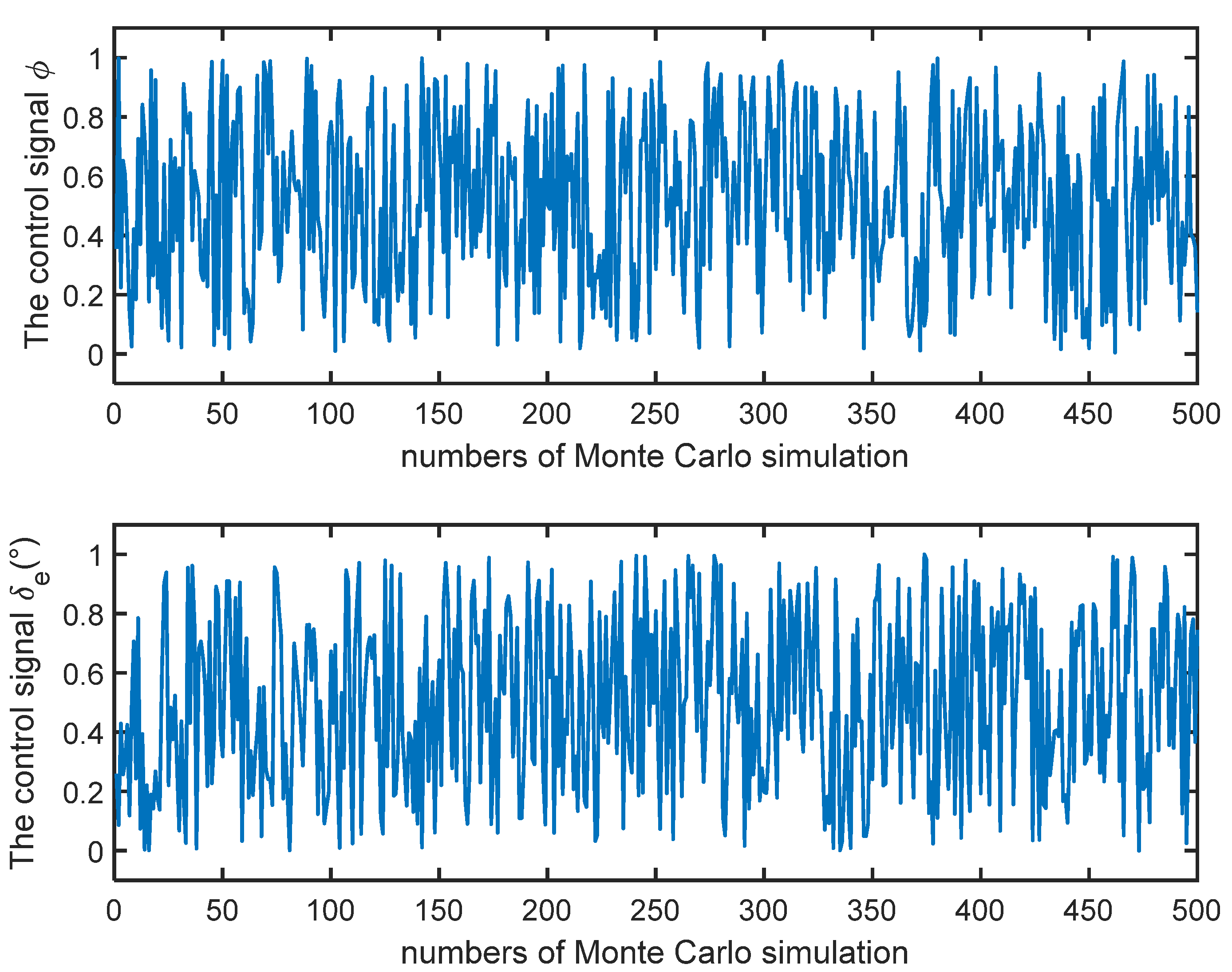

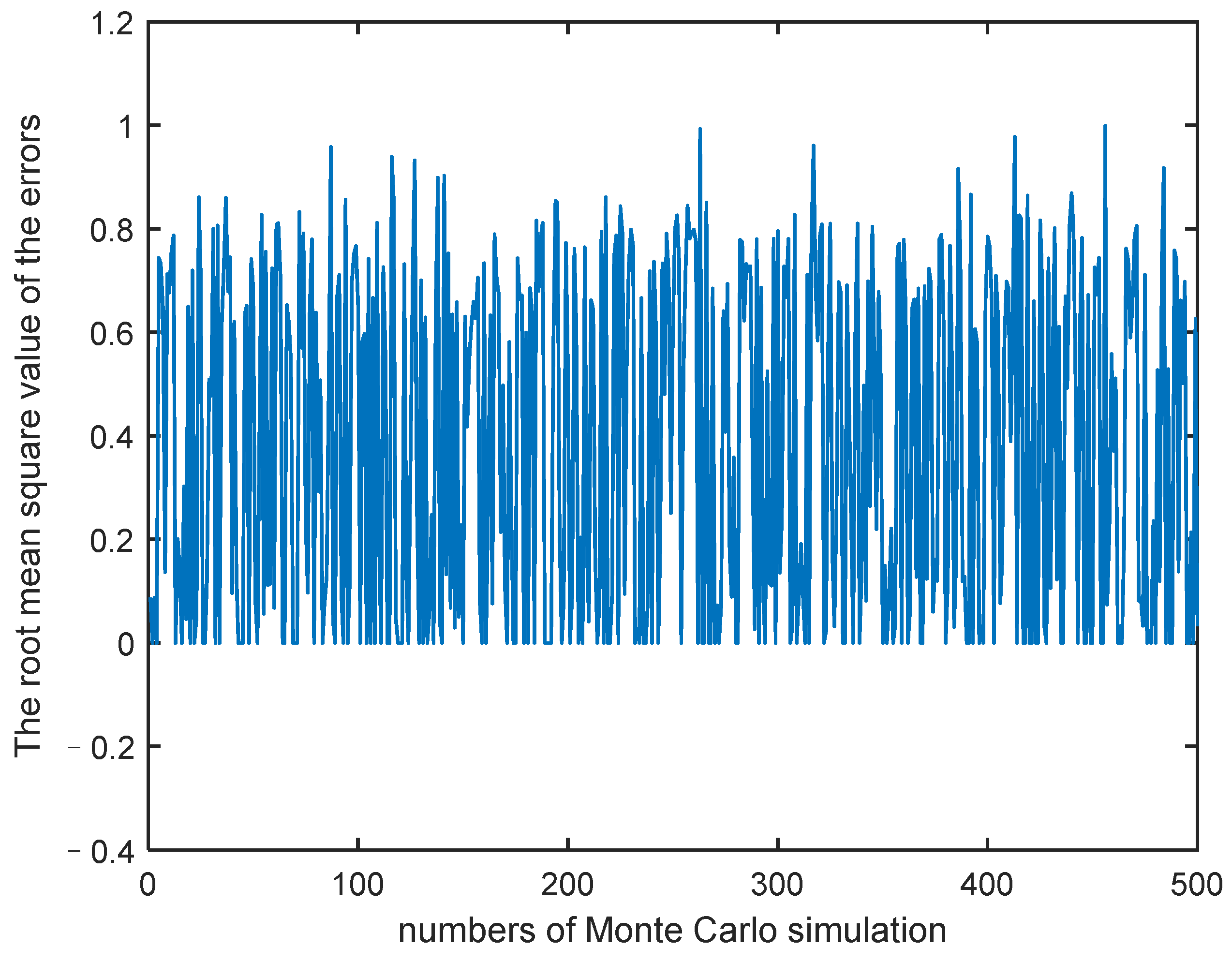

Firstly, in order to verify the effectiveness of the identification method, simulation analysis is carried out under the randomly generated constant control signals. A total of 500 times Monte Carlo simulations is performed. The constant control quantity of 500 times is shown in Figure 1, and the root mean square (RMS) values of the errors of the true system and identification system are shown in Figure 2. It is seen from Figure 2 that the RMS value of the final error is less than one, indicating that the identification model has high precision.

Figure 1.

500 times random control signals.

Figure 2.

The root mean square values of the errors of true system (TS) and identification system (IS).

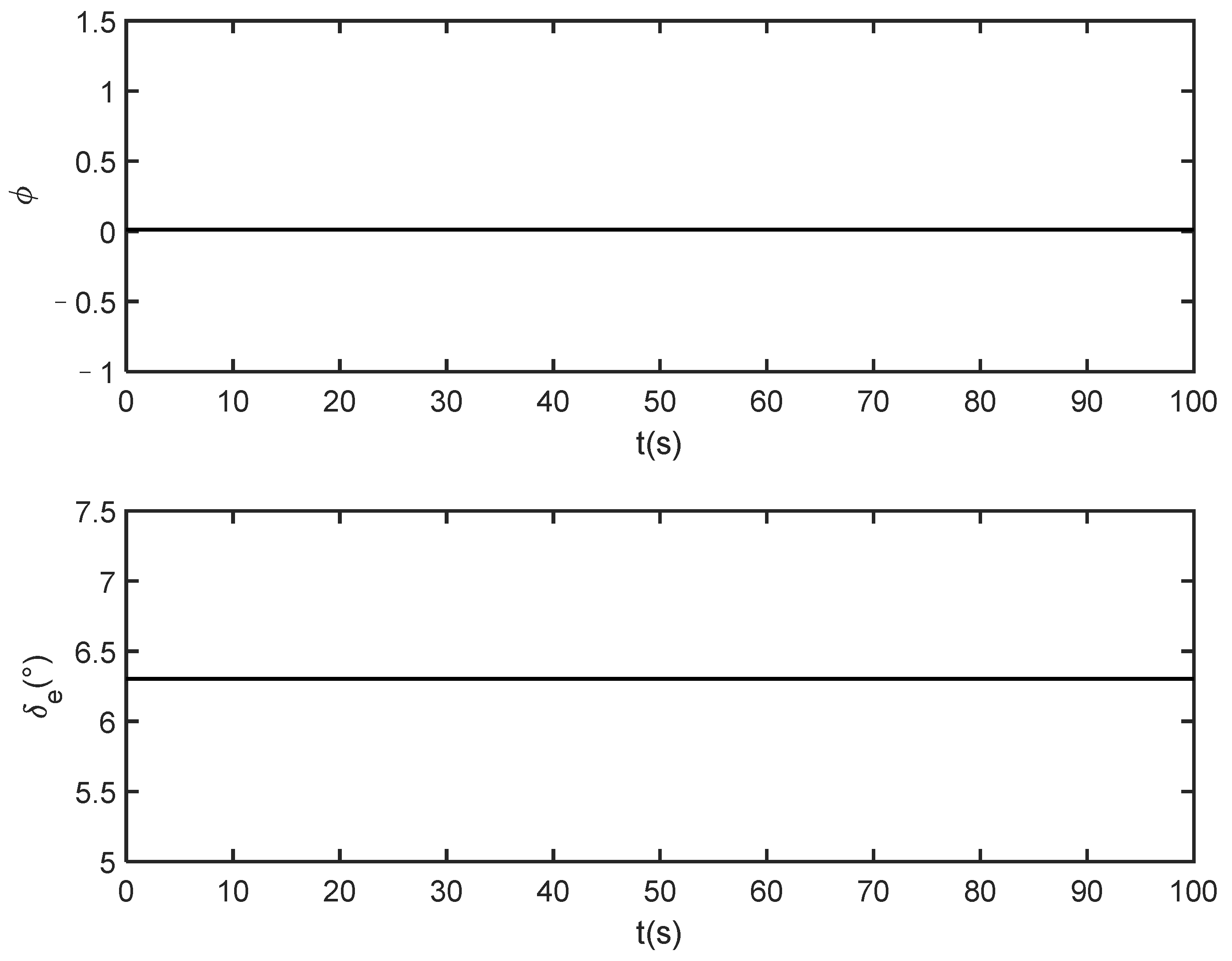

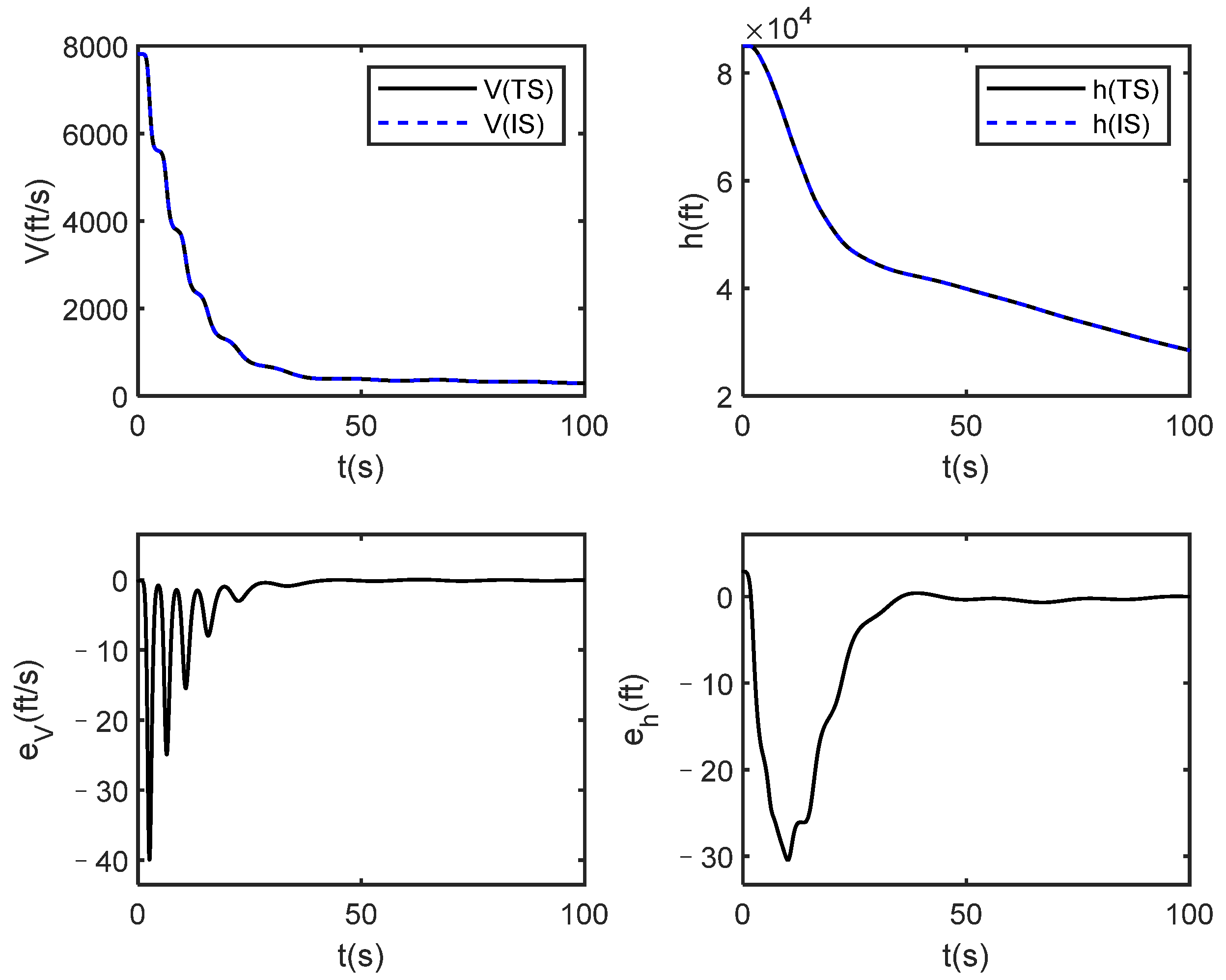

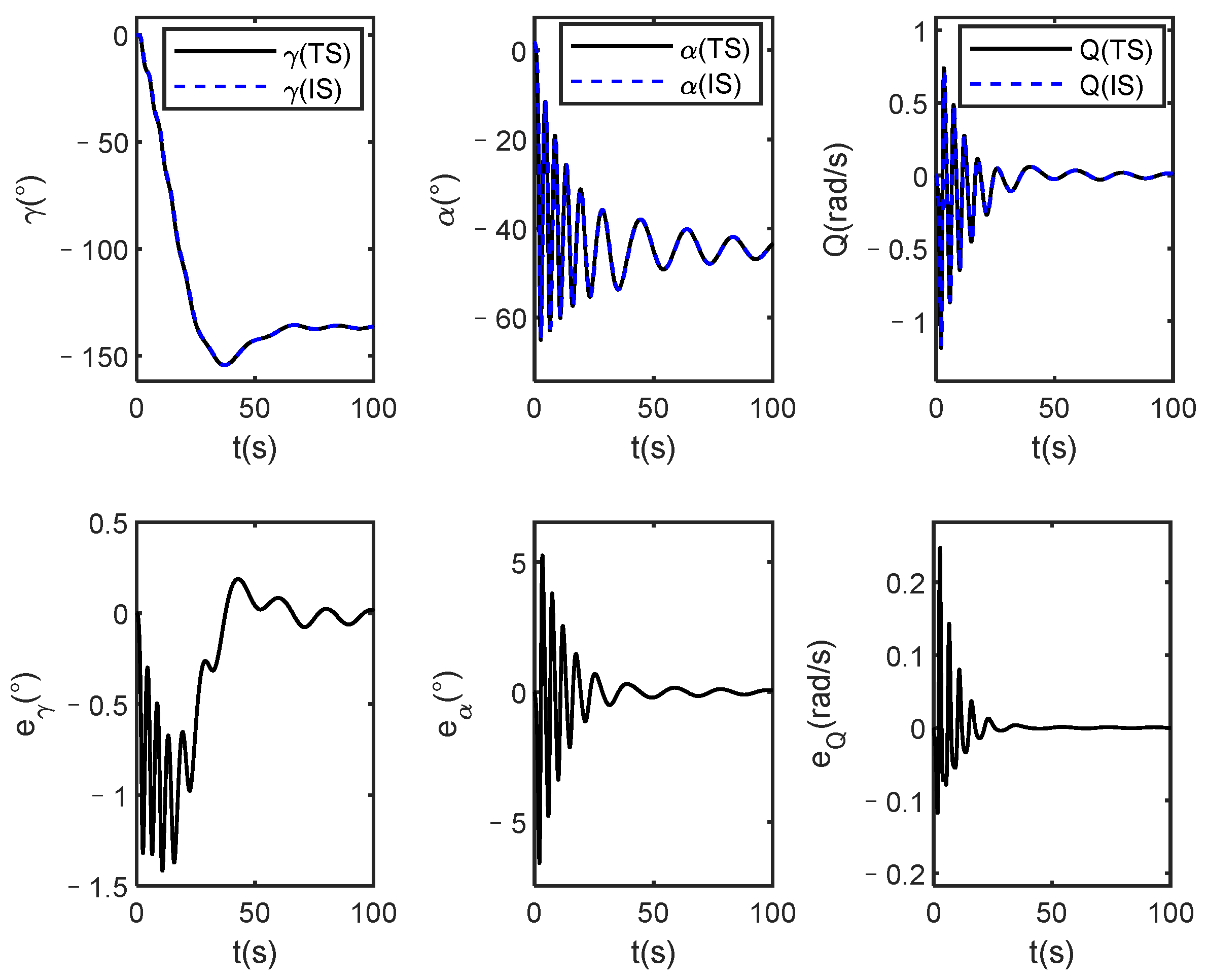

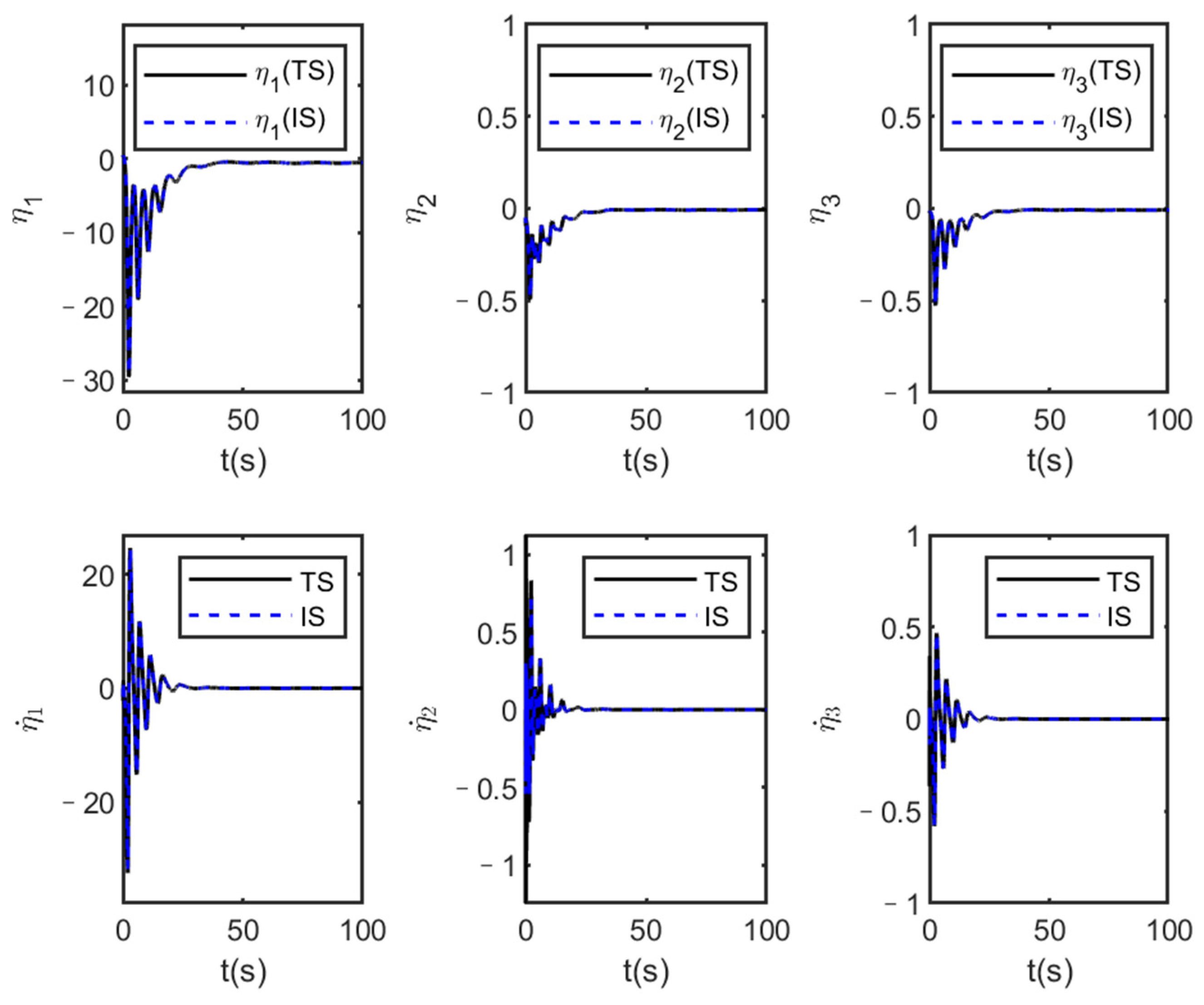

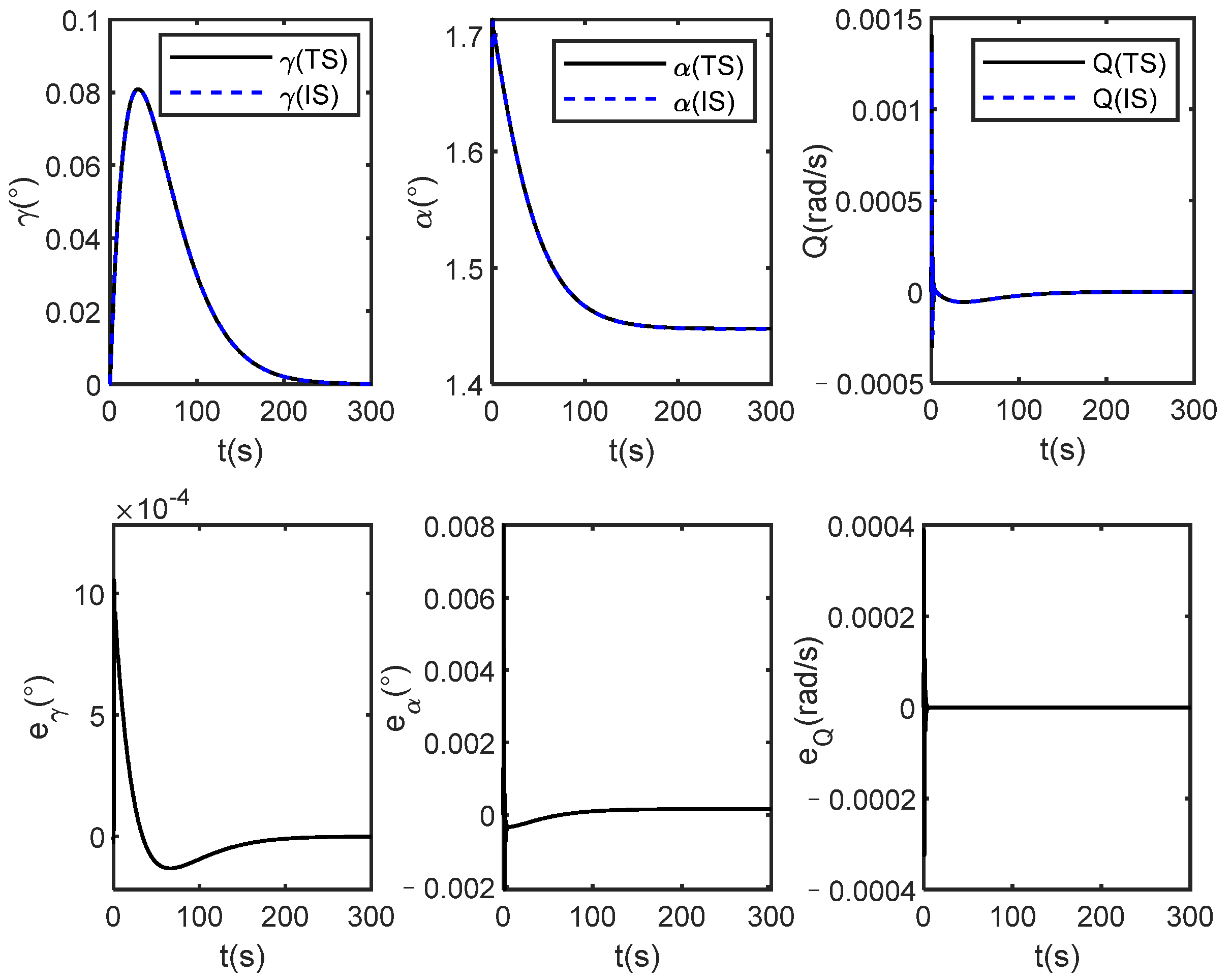

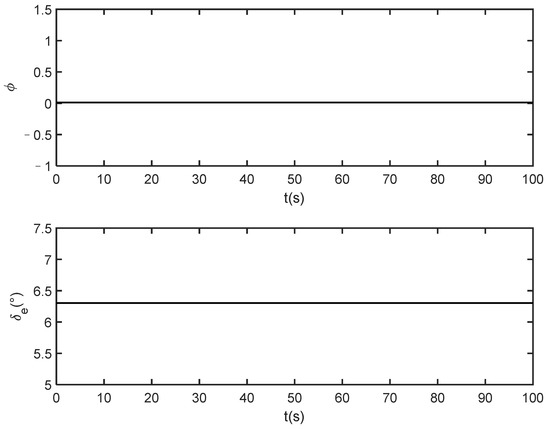

Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the simulation results under one of the constant control signals, and the control law is . In this case, since the control law is arbitrarily given, the rigid body states are divergent, but the states of the identification system are infinitely close to the actual system from the upper part of Figure 2 and Figure 3. In addition, it can be seen from the bottom half of Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 that all state errors finally converge to 0, which verifies that the proposed identification method is effective, and it is independent of the controller design.

Figure 3.

Control signals—stochastic constant control law u.

Figure 4.

Outputs and errors of true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under stochastic constant control law u.

Figure 5.

Altitude angles and errors of true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under stochastic constant control law u.

Figure 6.

The flexible states of true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under stochastic constant control law u.

5.2. System Identification and Tracking under Dynamic Inverse Control

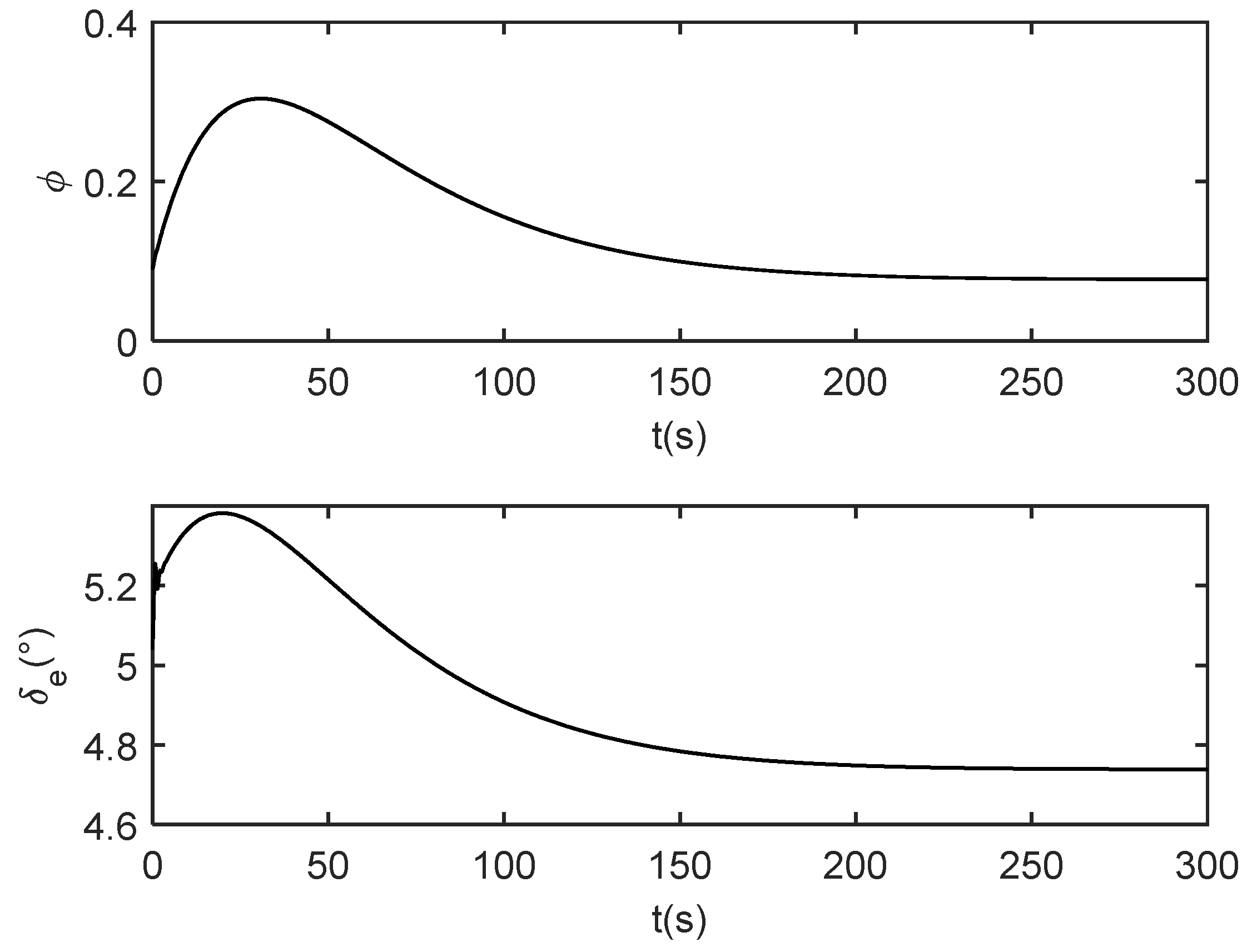

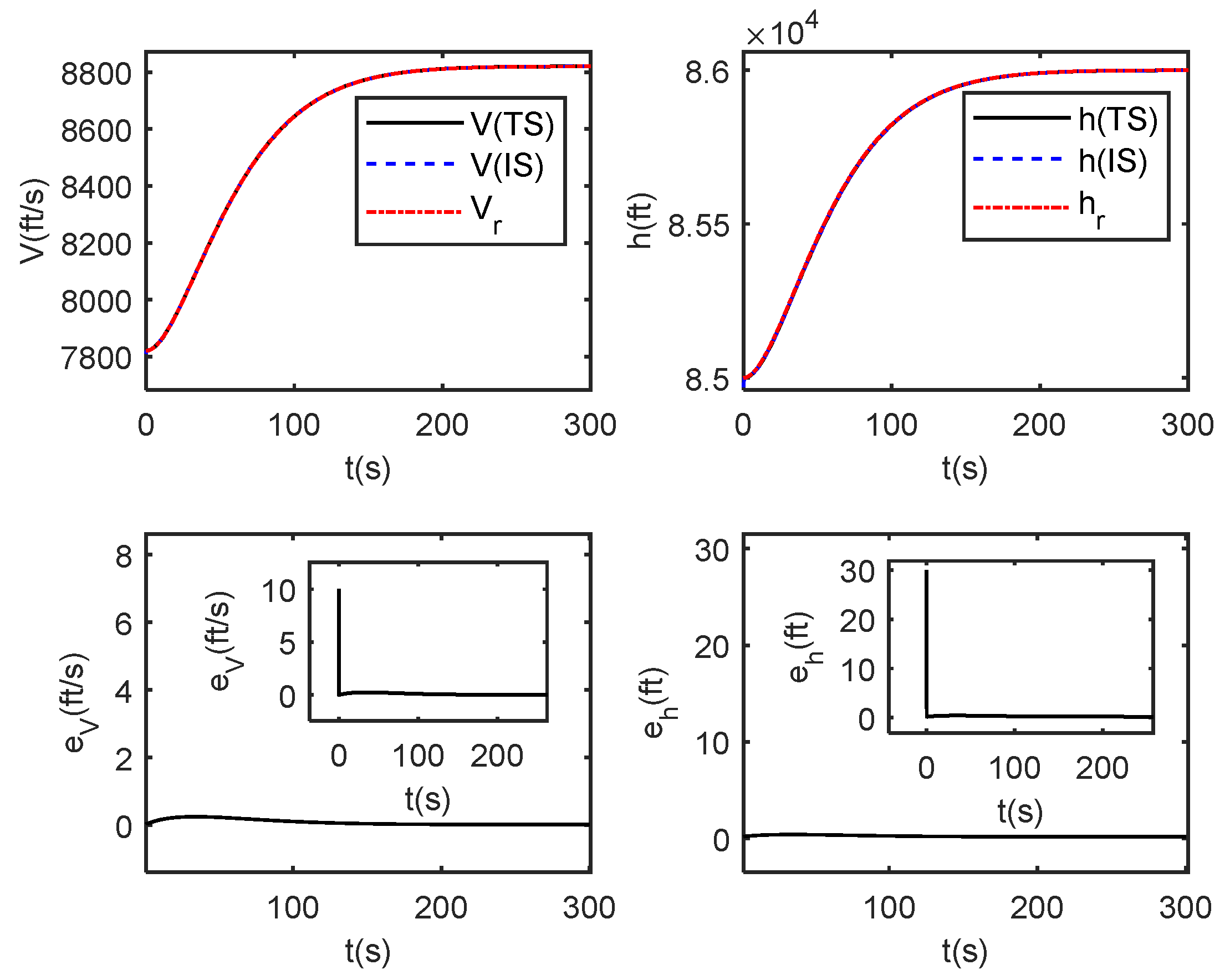

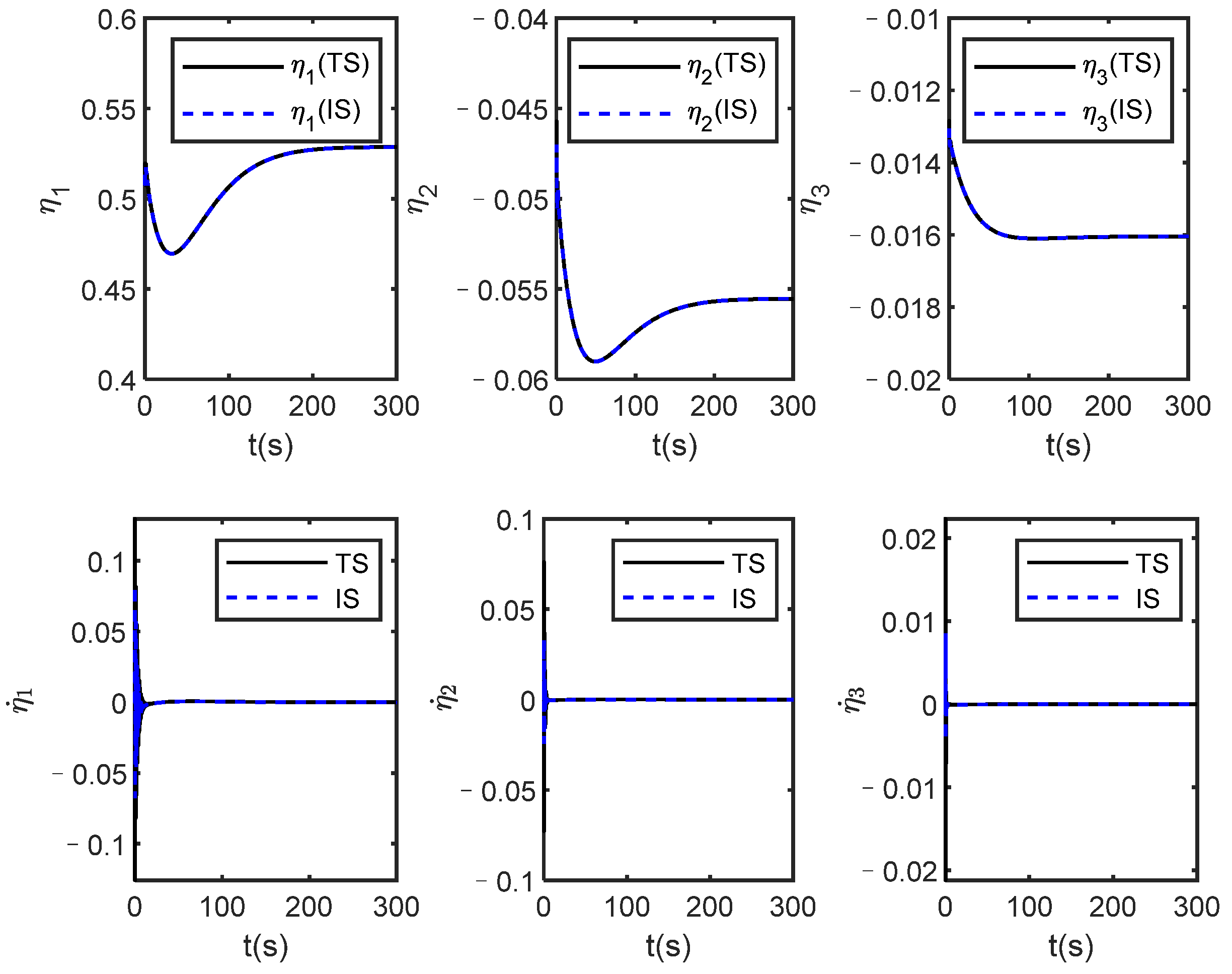

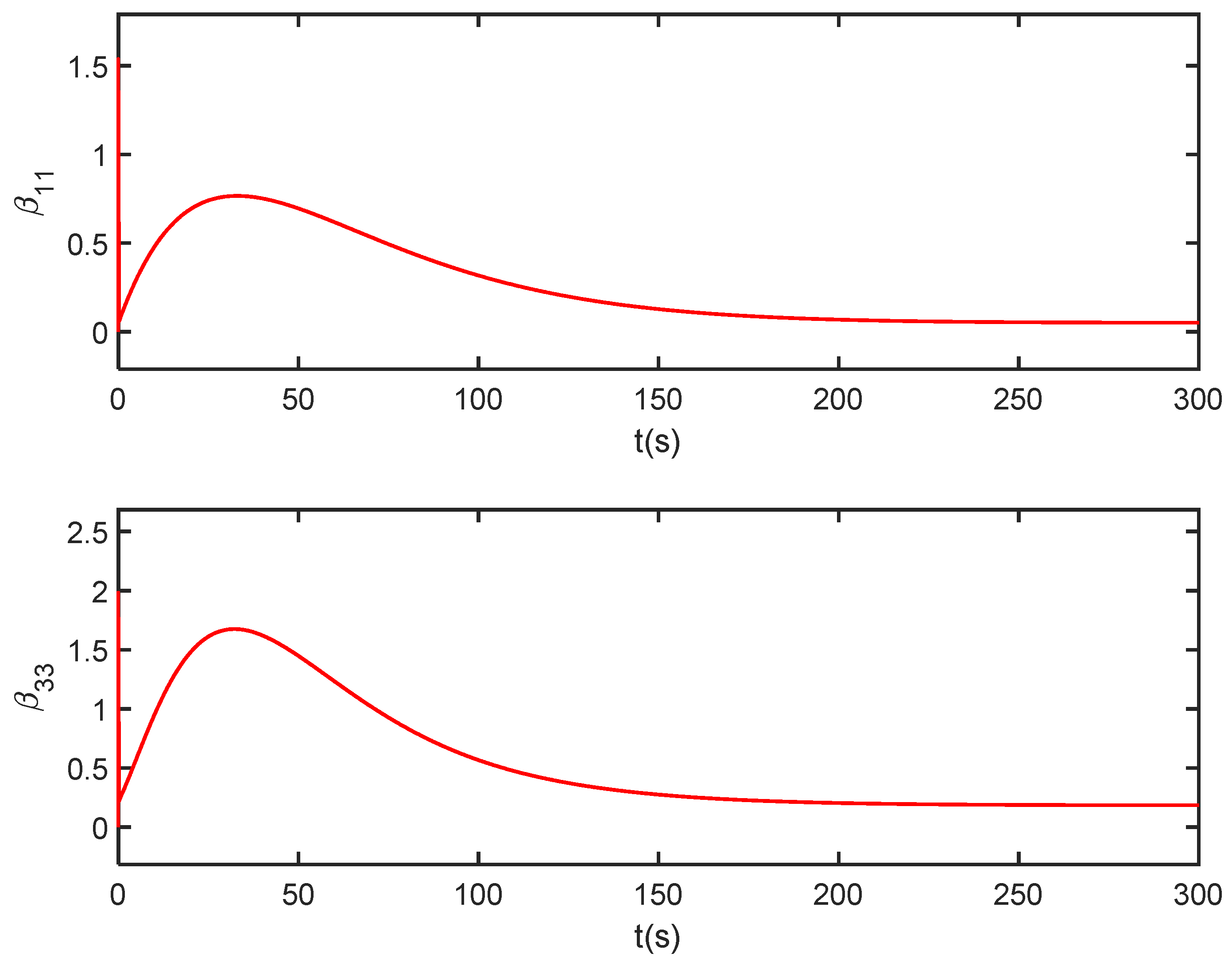

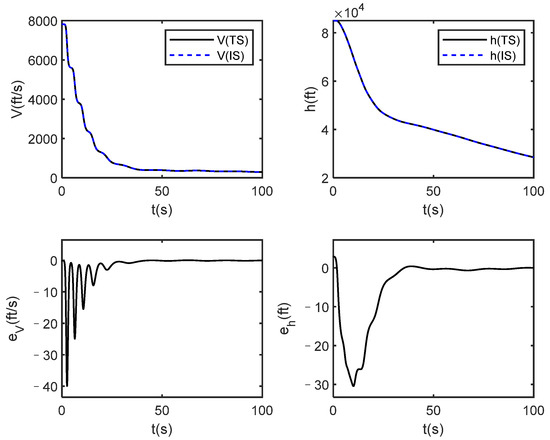

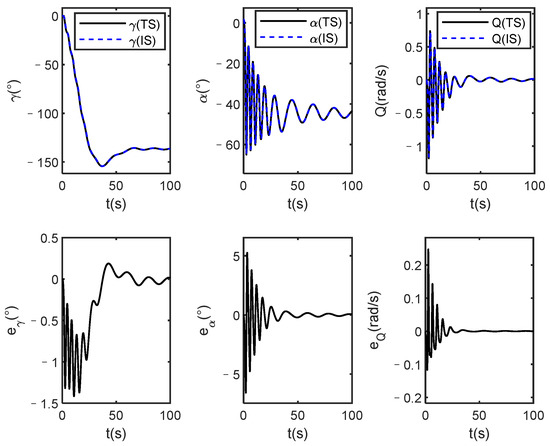

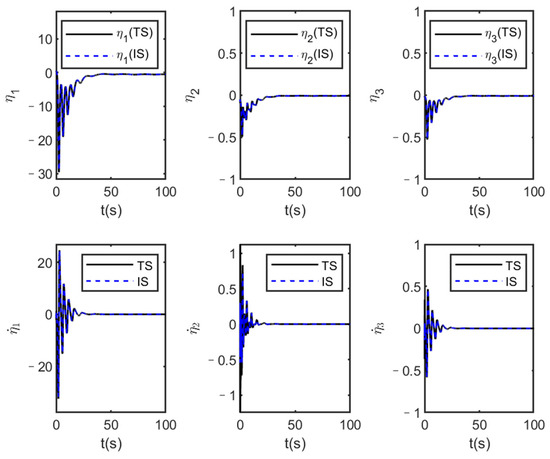

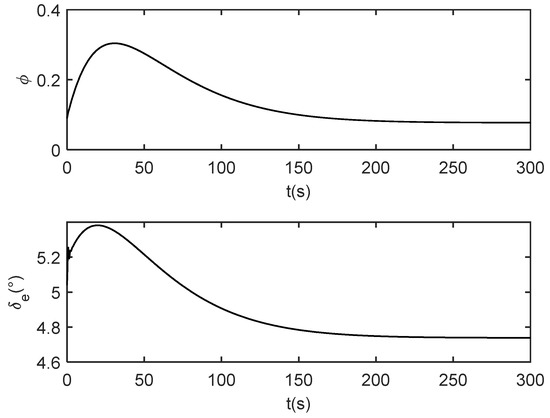

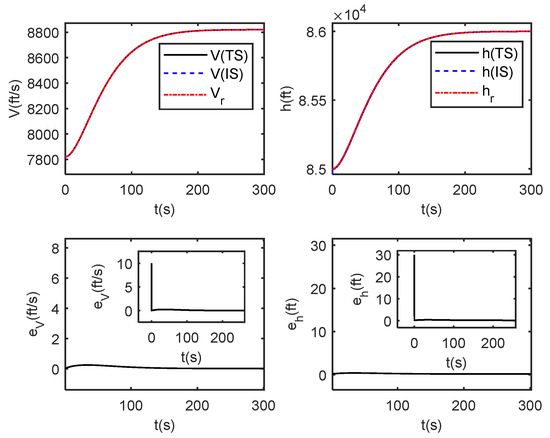

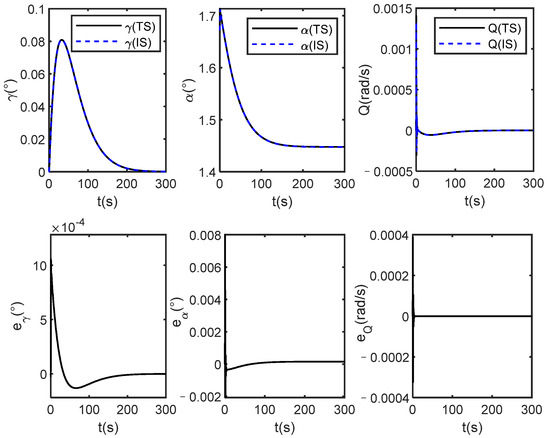

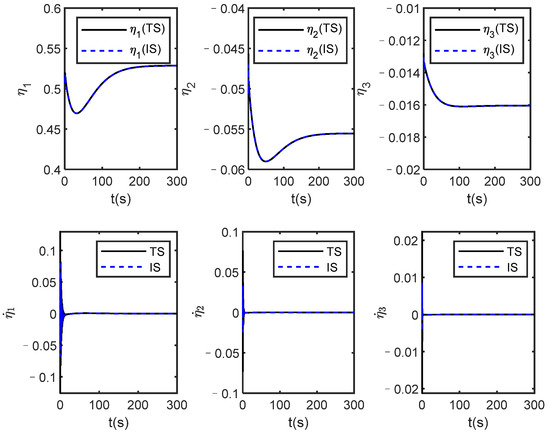

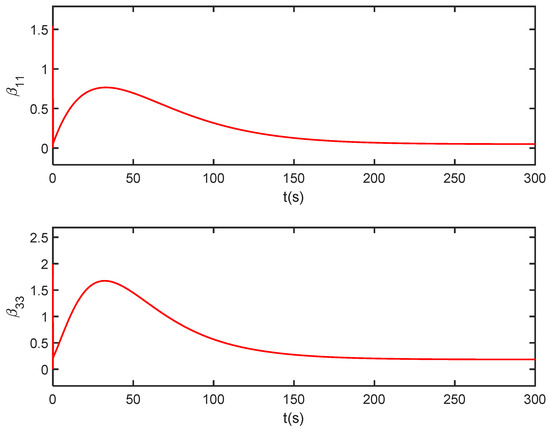

Secondly, in order to verify the effectiveness of the dynamic inverse control based on the identification model. The simulation results under dynamic inverse control law are given, as shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, and the curves of the estimated parameter and are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 7.

Dynamic inverse control law.

Figure 8.

Output tracking curves and errors between true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under dynamic inverse control.

Figure 9.

Altitude angles and errors of true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under dynamic inverse control.

Figure 10.

The flexible states of true system (TS) and identification system (IS) under dynamic inverse control.

Figure 11.

Curves of the estimated parameter and under dynamic inverse control.

In this case, the vehicle starts at initial trim conditions as listed in Table 2. and tracks the reference trajectories of velocity and altitude generated by the second-order filters with natural frequency and the damping ratio .

where the final reference commands are and .

Table 2.

States at initial trim conditions.

It is seen from Figure 8 that both the output of the actual system and the identification system track the given reference signal, and it is also seen that the identification system state quickly follows the actual system state. In addition, the attitude angle and elastic state of the identification system can also quickly converge to the state of the actual system as shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. These show that the designed adaptive DNN identification method and dynamic inverse controller are effective. Additionally, from Figure 11, it is seen that the estimated values of the parameter and are not equal to 0 throughout the flight process which indicates that the selected parameters are valid.

Further observation of the simulation results under constant control law and dynamic inverse control, and it can be seen that under dynamic inverse control, the states of the identification system approach the states of the real system faster, because the weighting coefficient of the DNN is affected by the control law as shown in Equation (16).

In summary, although the DNN identification method is independent of the control law design, its performance will be affected by the control law.

5.3. Comparison with Back-Stepping Control Method

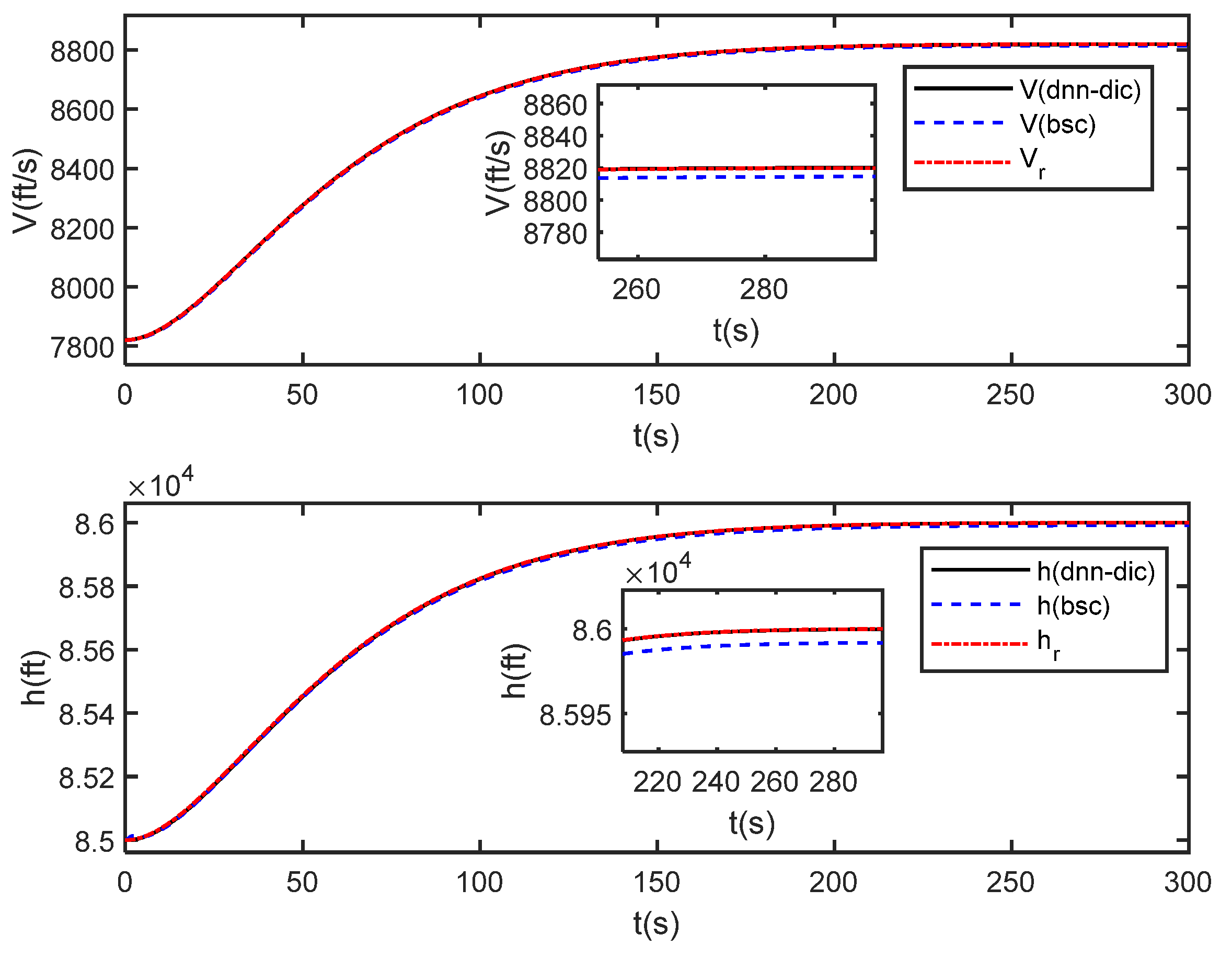

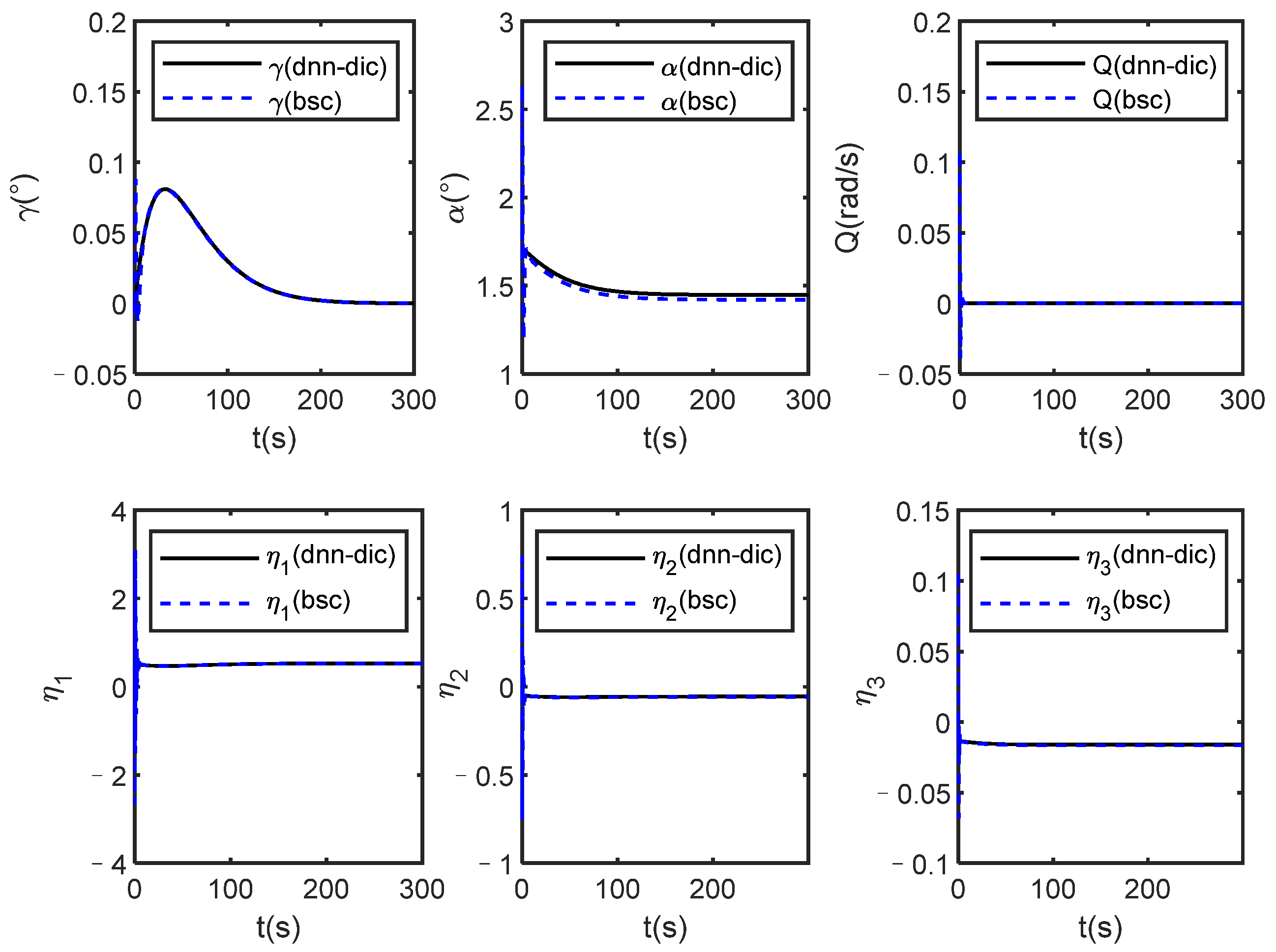

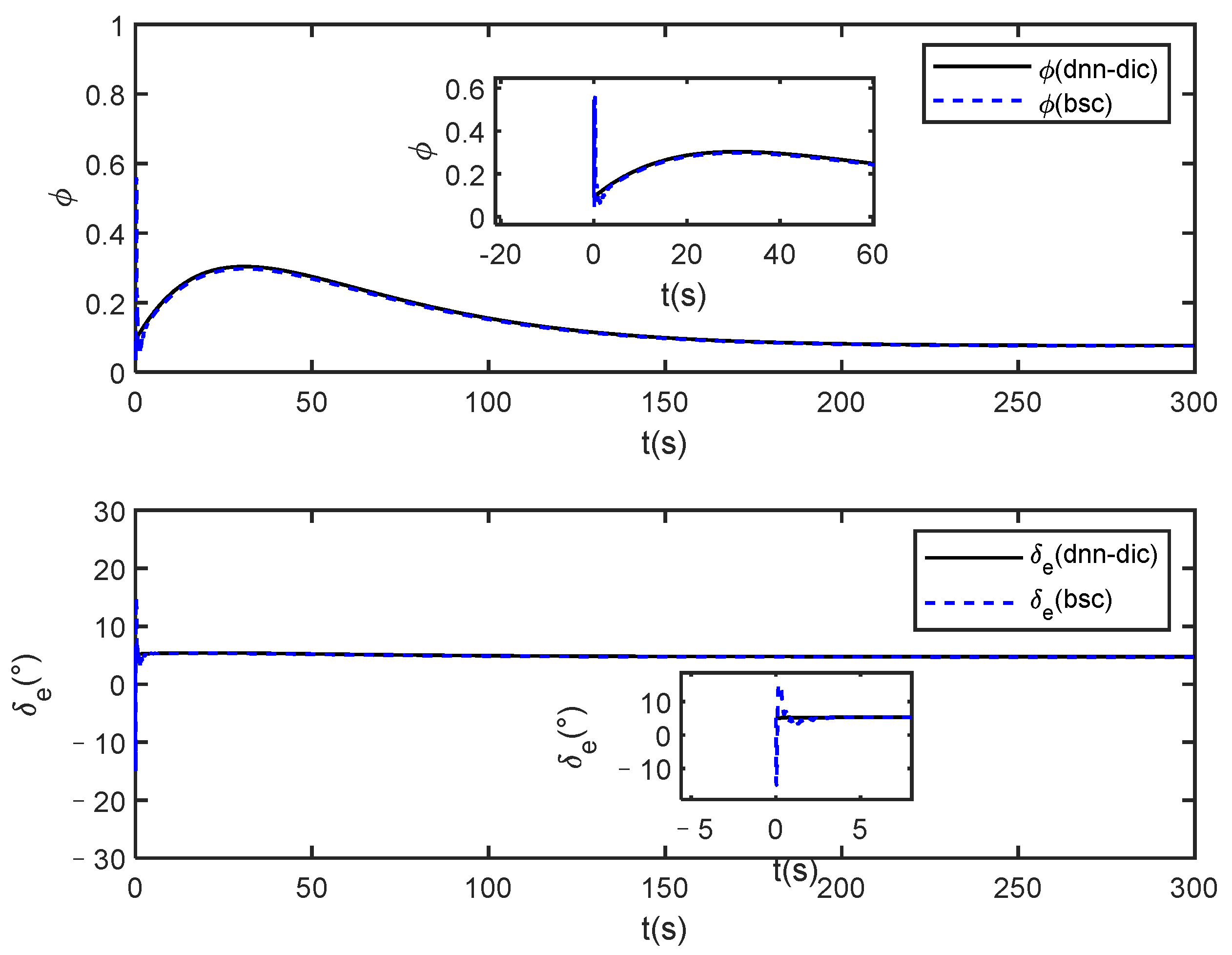

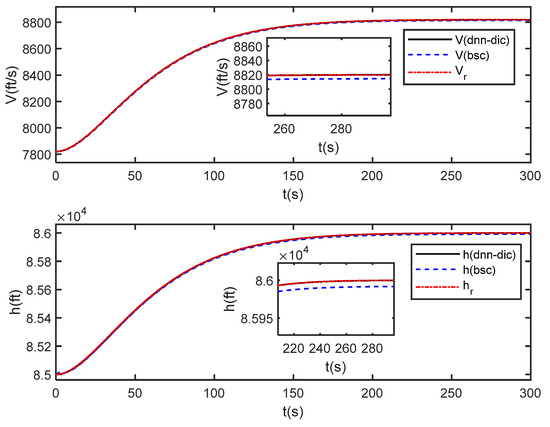

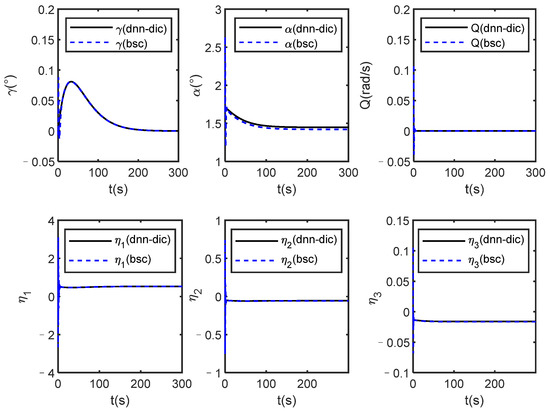

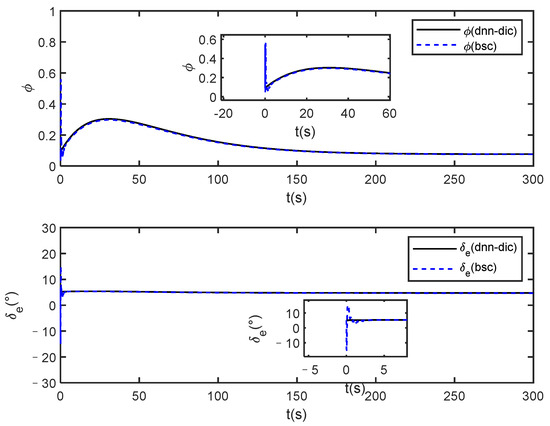

In order to illustrate the advantages of the proposed method, the proposed method is compared with the back-stepping control method [41]. The simulation conditions are set the same as Section 5.2, and the comparison curves of simulation results are shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 12.

Comparison of trajectory tracking curves under dynamic neural network based dynamic inverse control (dnn-dic) and back-stepping control (bsc).

Figure 13.

Comparison curves of other states under dnn-dic and bsc.

Figure 14.

Control law comparison curve.

It can be seen from Figure 12 that both methods can track the given reference signals, and the local magnifications show that the proposed method has smaller steady-state tracking errors. The states of the HVs all converge under the two methods from Figure 13, and the back-stepping control method requires greater control initially from the local magnification of Figure 14.

6. Conclusions

In this article, a dynamic inverse control method based on DNN is proposed to achieve the trajectory tracking control for a FAHV. The designed DNN identification model does not need to know the motion equation of FAHV, and the parameters can be designed independently of the control law which is beneficial to engineering applications. The dynamic inverse control law is designed based on the identification model, the complex model transformations are avoided, and the controller design process is simplified which can be verified by the simulation. In future research, more practical problems faced by FAHV, such as constraints, external interference, and unpredictable elastic modes, will be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G. and W.T.; methodology, H.G. and W.T.; software, Z.C.; validation, Z.C.; formal analysis, H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.; writing—review and editing, H.G. and W.T.; supervision, H.G. and W.T.; project administration, H.G. and W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62063018 and the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province under Grant 22JR5RA225.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zehong, D.; Yinghui, L.; Maolong, L.; Renwei, Z. Adaptive accurate tracking control of HFVs in the presence of dead-zone and hysteresis input nonlinearities. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 642–651. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.T.; Serrani, A.; Yurkovich, S.; Bolender, M.A.; Doman, D.B. Control-oriented modeling of an air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2007, 30, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewei, Z.; Rui, L. Typical adaptive neural control for hypersonic vehicle based on higher-order filters. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2020, 31, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z. Robust adaptive neural control of nonminimum phase hypersonic vehicle model. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 51, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Lei, H.; Gao, Y. Robust tracking control of hypersonic flight vehicles: A continuous model-free control approach. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 161, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Kim, S.-H.; Tahk, M.-J. Optimality of linear time-varying guidance for impact angle control. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 2802–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Dou, J. The design of optimal guidance law with multi-constraints using block pulse functions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibo, D.; Xiaokui, Y.; Guangshan, C.; Jiashun, S. Review of control and guidance technology on hypersonic vehicle. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Su, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, C. Autonomous dispatch trajectory planning on flight deck: A search-resampling-optimization framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 119, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinwei, W.; Jie, L.; Xichao, S.; Haijun, P.; Xudong, Z.; Chen, L. A review on carrier aircraft dispatch path planning and control on deck. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 3039–3057. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Lv, W.; Mi, H.; Hu, C.; Hu, Y. Tube-MPC Control via Notch Filter for Flexible Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicle with Actuator Fault. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4474884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W. Offset-free trajectory tracking control for hypersonic vehicle under external disturbance and parametric uncertainty. J. Franklin Inst. 2018, 355, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cai, Y. A fuzzy model predictive control based upon adaptive neural network disturbance observer for a constrained hypersonic vehicle. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 5927–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Bai, W.; Xie, Y. Fractional-order PI λ D sliding mode control for hypersonic vehicles with neural network disturbance compensator. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 103, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Y.; Xu, B.; Liang, X.; Yang, D. Aerodynamic/reaction-jet compound control of hypersonic reentry vehicle using sliding mode control and neural learning. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, W.; Wei, C.; Xu, T. Nonlinear disturbance observer based adaptive super-twisting sliding mode control for generic hypersonic vehicles with coupled multisource disturbances. Eur. J. Control 2021, 57, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z. Barrier Lyapunov function based reinforcement learning control for air-breathing hypersonic vehicle with variable geometry inlet. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Cheng, Z.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y. Online policy iteration ADP-based attitude-tracking control for hypersonic vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Ni, Z.; Sun, C.; He, H. Air-breathing hypersonic vehicle tracking control based on adaptive dynamic programming. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.F.; Wang, J.; Bu, X.W.; Jia, Y.J. Adaptive fuzzy tracking control for a constrained flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle based on actuator compensation. Int. J. Adv. Rob. Syst. 2016, 13, 1729881416671115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, R.; Huang, J. Novel auxiliary error compensation design for the adaptive neural control of a constrained flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. Neurocomputing 2016, 171, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, R. Novel adaptive neural control of flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicles based on sliding mode differentiator. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2015, 28, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, X.; He, G.; Huang, J. Novel adaptive neural control design for a constrained flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle based on actuator compensation. Acta Astronaut. 2016, 120, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Lei, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, C. A new adaptive neural control scheme for hypersonic vehicle with actuators multiple constraints. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 100, 3529–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, B. A simplified finite-time fuzzy neural controller with prescribed performance applied to waverider aircraft. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 30, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Jiang, B.; Lei, H. Nonfragile quantitative prescribed performance control of waverider vehicles with actuator saturation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 3538–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovithakis, G.A.; Christodoulou, M.A. Adaptive control of unknown plants using dynamical neural networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 1994, 24, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovithakis, G.A.; Christodoulou, M.A. Direct adaptive regulation of unknown nonlinear dynamical systems via dynamic neural networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 1995, 25, 1578–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Deng, X. Recurrent neural network-based model predictive control for multiple unmanned quadrotor formation flight. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 2019, 7272387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, E.; Selişteanu, D.; Şendrescu, D.; Ionete, C. Neural networks-based adaptive control for a class of nonlinear bioprocesses. Neural Comput Appl. 2010, 19, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Mili, L. Sparse state recovery versus generalized maximum-likelihood estimator of a power system. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 1104–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thüne, P.; Enzner, G. Maximum-likelihood approach with Bayesian refinement for multichannel-Wiener postfiltering. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2017, 65, 3399–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Lai, C.; Kar, N.C. Expectation-maximization particle-filter-and Kalman-filter-based permanent magnet temperature estimation for PMSM condition monitoring using high-frequency signal injection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2016, 13, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolender, M.A.; Doman, D.B. Nonlinear longitudinal dynamical model of an air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. J. Spacecr Rockets 2007, 44, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, L. Nonlinear Adaptive Controller Design for Air-Breathing Hypersonic Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yu, Z. Adaptive neural network disturbance observer based nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control for a constrained flexible air-breathing hypersonic vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 233, 2642–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Yuan, R.; Tan, X.; Yi, J. Active robust control of uncertainty and flexibility suppression for air-breathing hypersonic vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 42, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, N.; Saratchandran, P.; Li, Y. Fully Tuned Radial Basis Function Neural Networks for Flight Control; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-X. Stable adaptive fuzzy control of nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 1993, 1, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G.C.; Mayne, D.Q. A parameter estimation perspective of continuous time model reference adaptive control. Automatica 1987, 23, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yi, J.; Pu, Z.; Tan, X. Fixed-time sliding mode disturbance observer-based nonsmooth backstepping control for hypersonic vehicles. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 4377–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).