Sulfonated Polyethersulfone Membranes for Brackish Water Desalination: Fabrication, Characterization, and Electrodialysis Performance Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

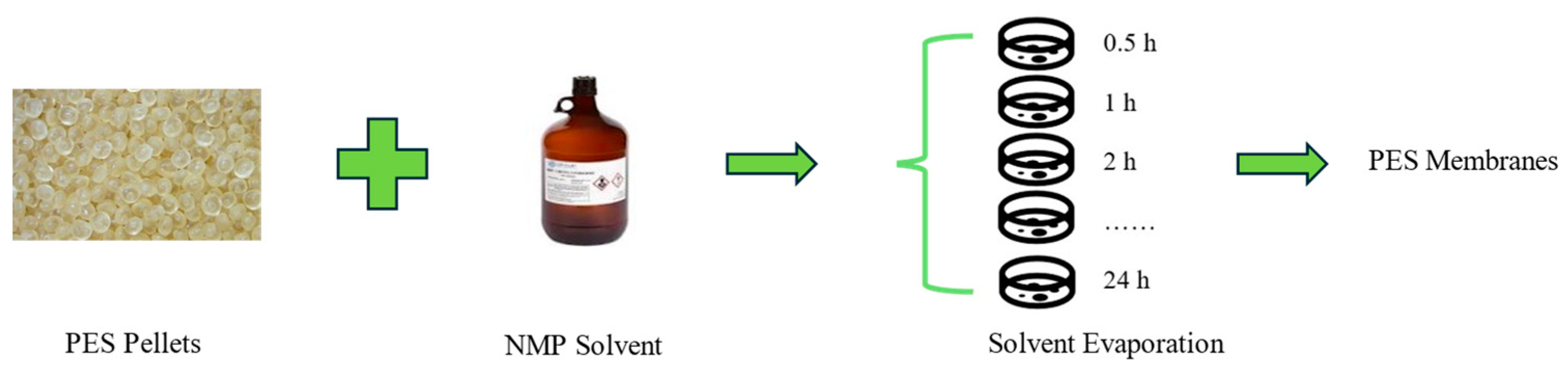

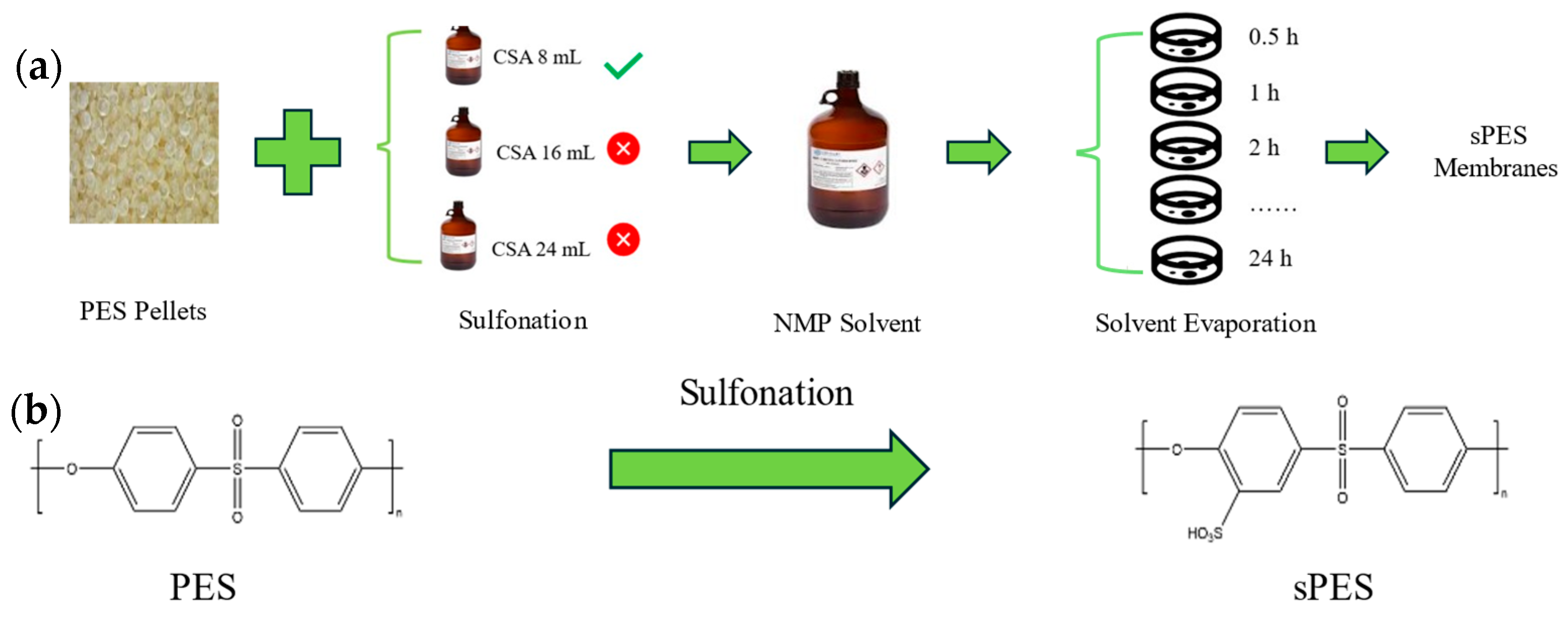

2.2. Fabrication of PES and sPES Membranes

2.2.1. Fabrication of PES Membranes

2.2.2. Fabrication of sPES Membranes

2.3. Characterization of PES and sPES Membranes

2.3.1. Degree of Sulfonation (DS) Measurements

2.3.2. Ion-Exchange Capacity (IEC) Measurements

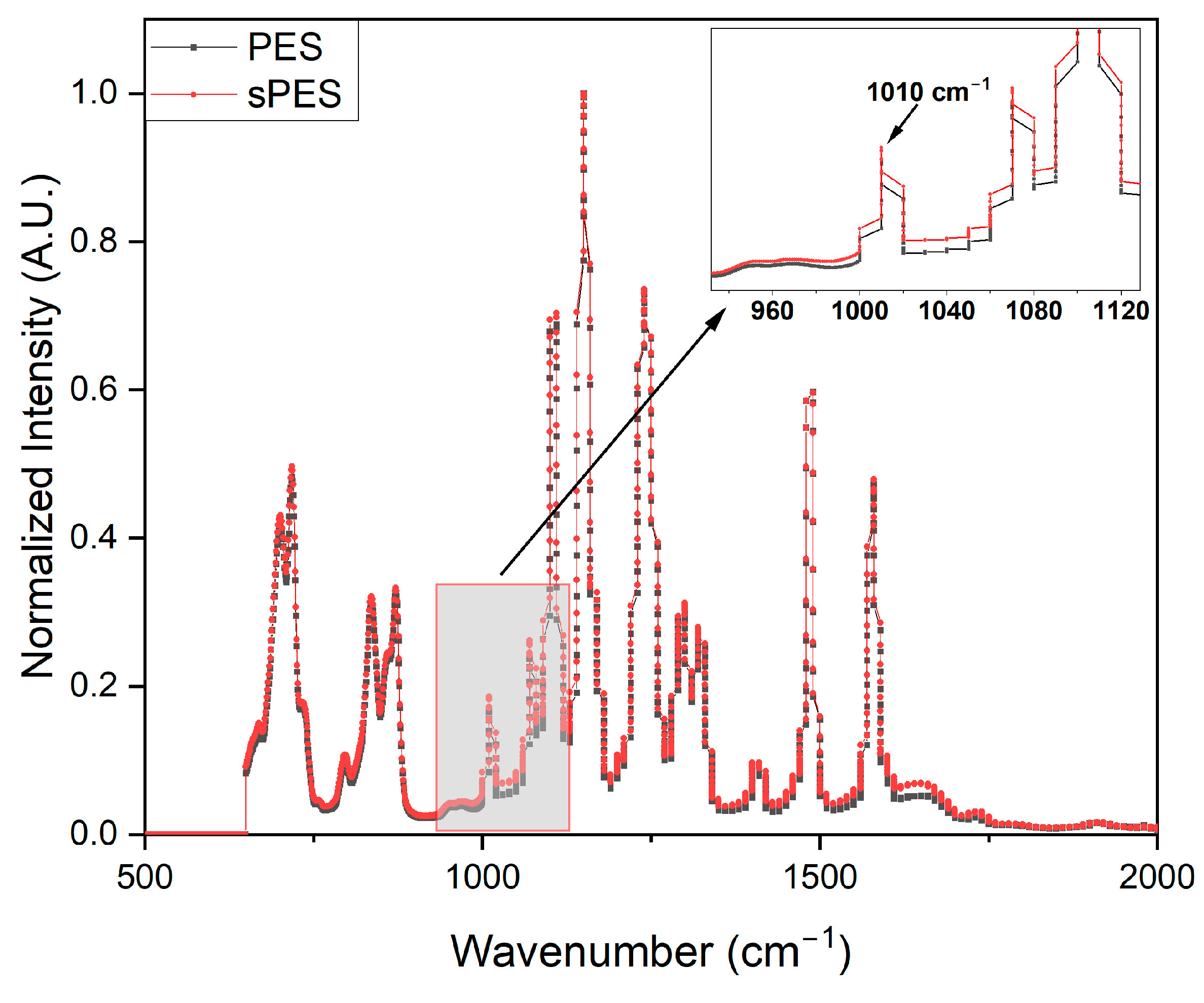

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared-Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR) Measurements

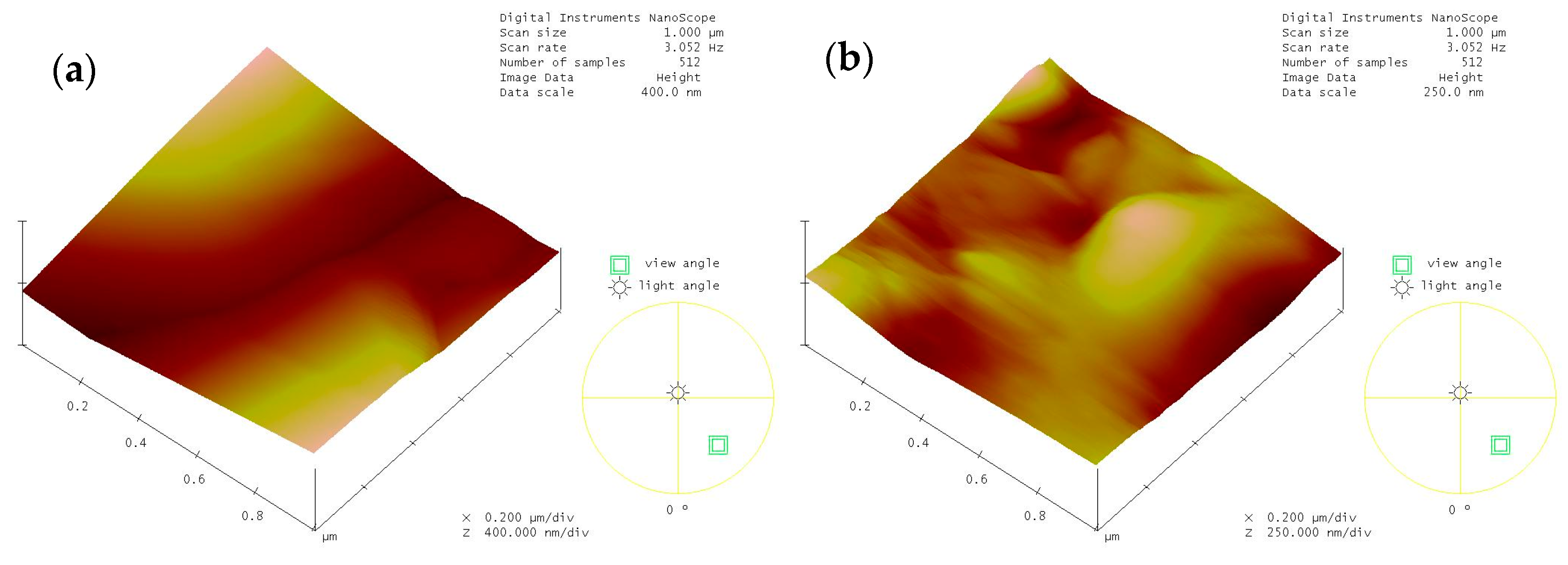

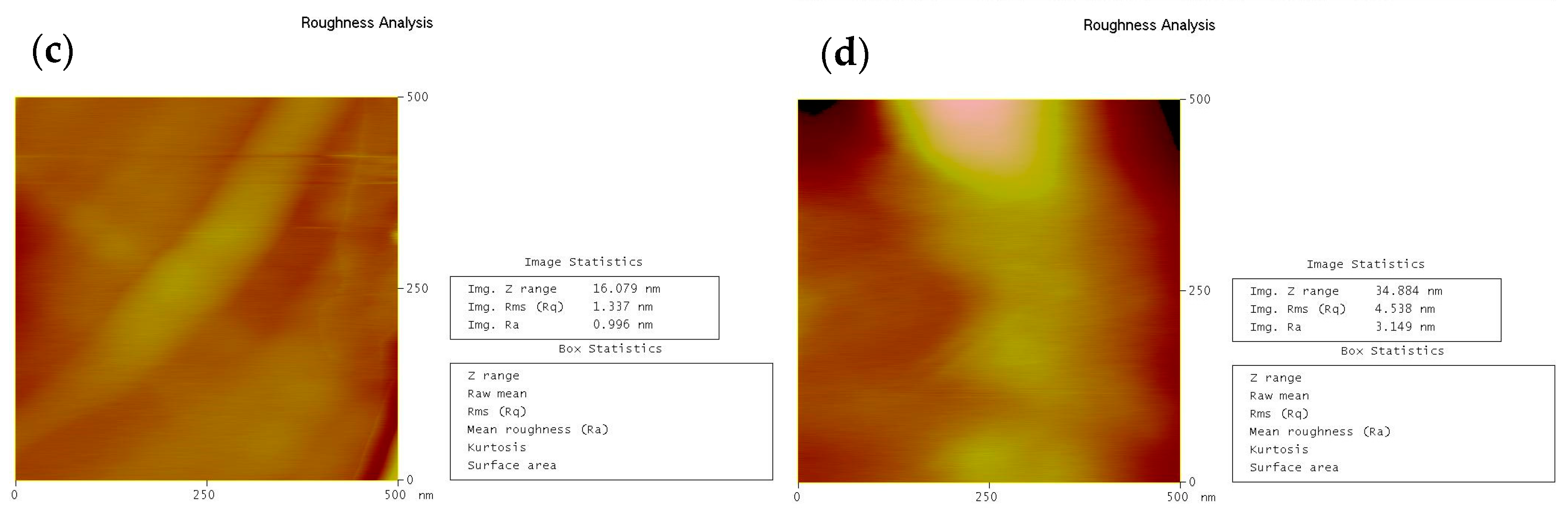

2.3.4. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Measurements

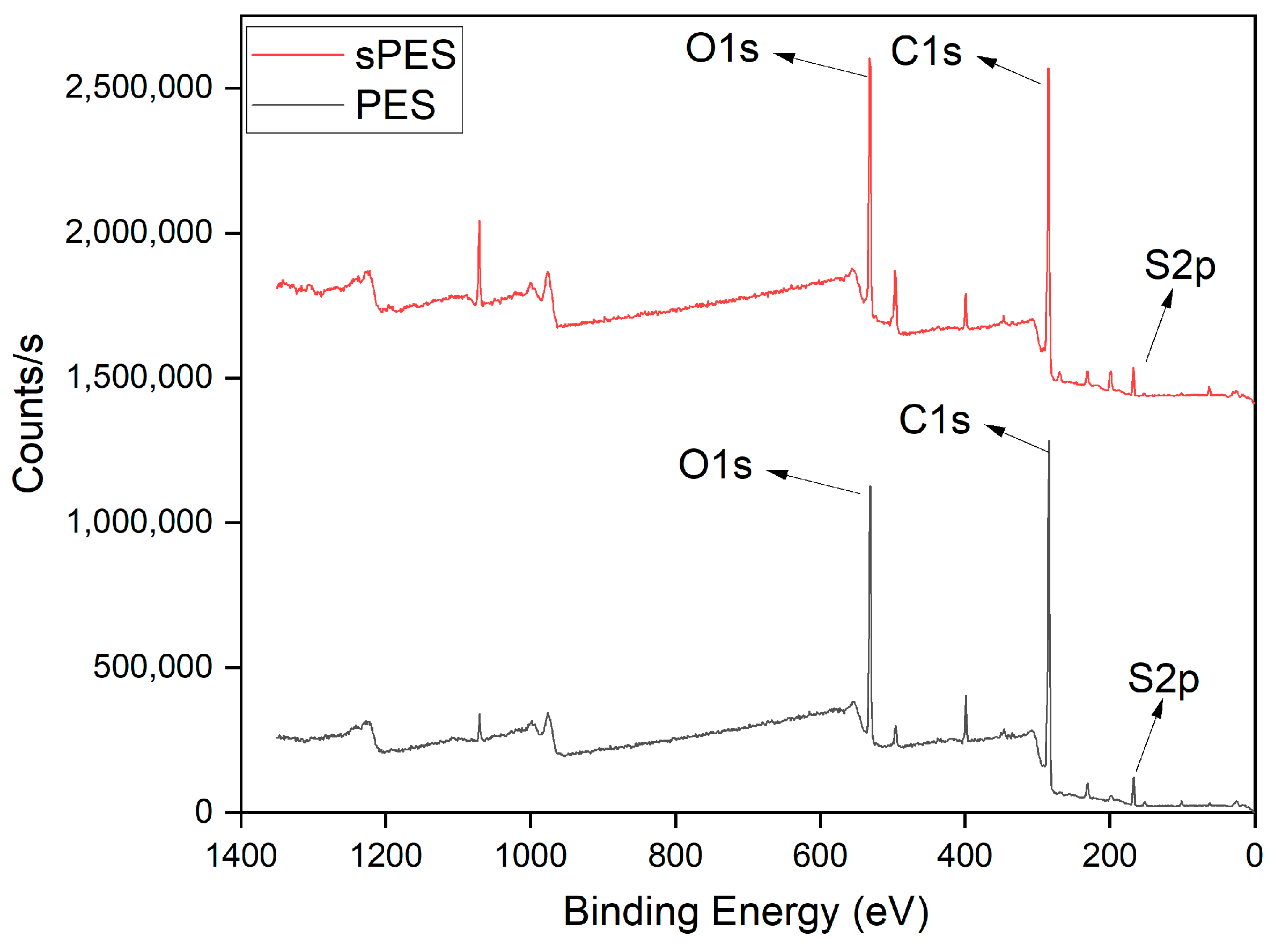

2.3.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Measurements

2.4. Electrodialysis Desalination Performance Testing

3. Results and Discussions

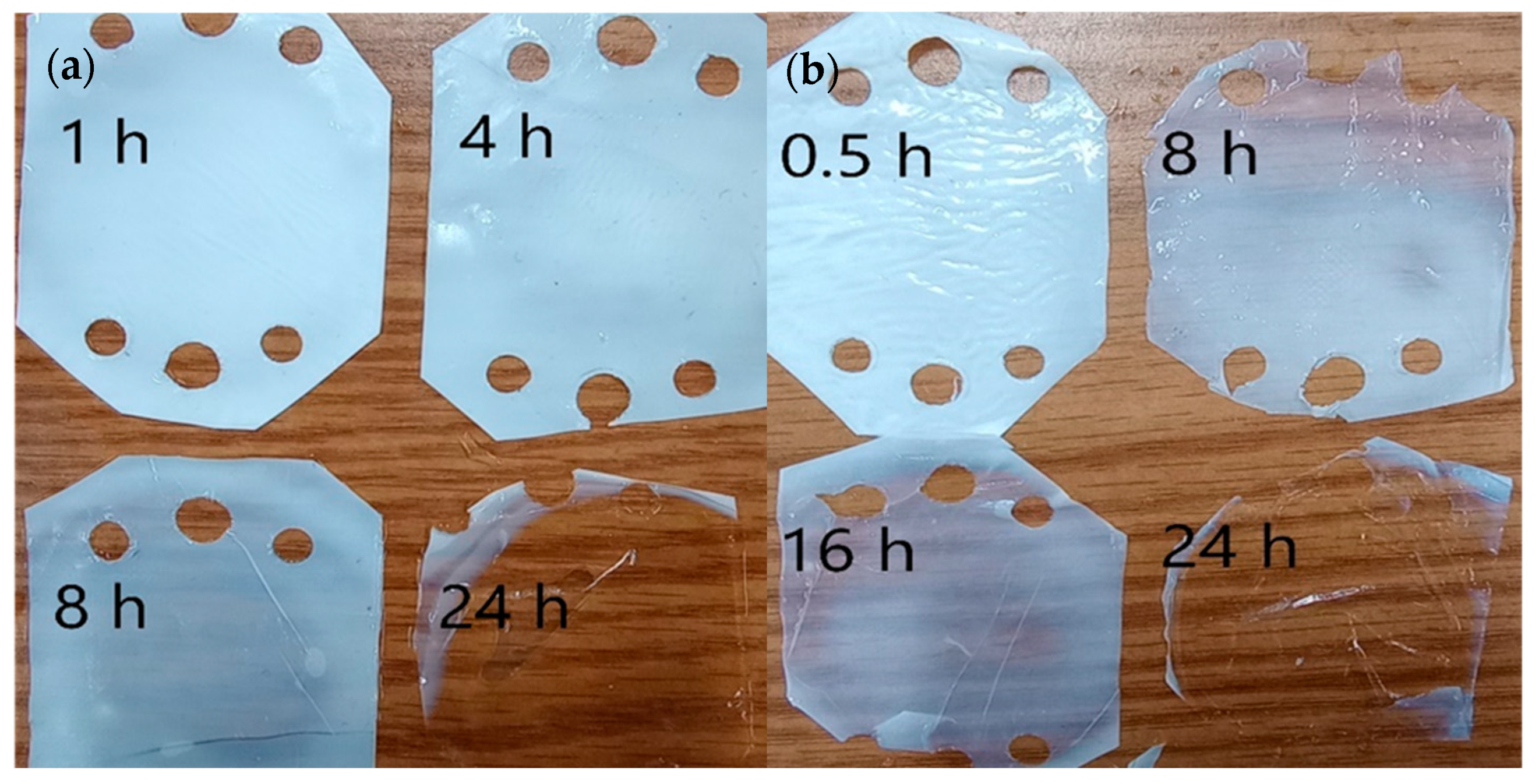

3.1. Examples of Fabricated Membranes

3.2. Membrane Fabrication Condition Optimization

3.3. Membrane Characterization

3.4. Performance Testing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, Y.J.; Goh, K.; Goto, A.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R. Uranium and lithium extraction from seawater: Challenges and opportunities for a sustainable energy future. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 22551–22589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinis, A.; Papadopoulos, A.I.; Seferlis, P. Optimal Operational Profiles in an Electrodialysis Unit for Ion Recovery. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 88, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juve, J.M.A.; Christensen, F.M.S.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Z. Electrodialysis for metal removal and recovery: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.M.; Porada, S.; Elimelech, M.; Dykstra, J.E. Tutorial review of reverse osmosis and electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Trindade, L.G.; Zanchet, L.; Souza, J.C.; Leite, E.R.; Martini, E.M.A.; Pereira, E.C. Enhancement of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone)-based proton exchange membranes doped with different ionic liquids cations. Ionics 2020, 26, 5661–5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solonchenko, K.; Kirichenko, A.; Kirichenko, K. Stability of Ion Exchange Membranes in Electrodialysis. Membranes 2023, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Fabrication of PVDF cation exchange membrane for electrodialysis: Influence and mechanism of crystallinity and leakage of co-ions. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 695, 122389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubenko, D.V.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Yaroslavtsev, A.B. Ion exchange membranes based on radiation-induced grafted functionalized polystyrene for high-performance reverse electrodialysis. J. Power Sources 2021, 511, 230460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lim, J.; Wang, M.; Mi, B.; Miller, D.J.; McCloskey, B.D. Polyamide-Based Ion Exchange Membranes: Cation-Selective Transport through Water Purification Membranes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Mai, Z.; Ortega, E.; Shen, J.; Gao, C.; Van der Bruggen, B. Symmetrically recombined nanofibers in a high-selectivity membrane for cation separation in high temperature and organic solvent. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 20006–20012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Zheng, C.; Mondal, A.N.; Hossain, M.; Wu, B.; Emmanuel, K.; Wu, L.; Xu, T. Preparation of anion exchange membranes from BPPO and dimethylethanolamine for electrodialysis. Desalination 2017, 402, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, S.; Yadav, V.; Sharma, P.P.; Kulshrestha, V. Zn-MOF@SPES composite membranes: Synthesis, characterization and its electrochemical performance. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Lin, Y.; Ma, H.; Jia, H.; Liu, X.; Lin, J. Preparation of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone) (SPEEK) membrane using ethanol/water mixed solvent. Mater. Lett. 2016, 169, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Huang, Q.; Dong, Y.; Duan, J.; Mo, D.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Yao, H. Preparation and ion separation properties of sub-nanoporous PES membrane with high chemical resistance. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 635, 119467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Luo, B.; Qian, Y.; Sotto, A.; Gao, C.; Shen, J. Three-Dimensional Stable Cation-Exchange Membrane with Enhanced Mechanical, Electrochemical, and Antibacterial Performance by in Situ Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 16619–16628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahlot, S.; Sharma, P.P.; Gupta, H.; Kulshrestha, V.; Jha, P.K. Preparation of graphene oxide nano-composite ion-exchange membranes for desalination application. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 24662–24670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Q.B.; Wang, D.; Wang, J. A novel porous asymmetric cation exchange membrane with thin selective layer for efficient electrodialysis desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.C.; Choi, J.G.; Tak, T.M. Sulfonated Polyethersulfone by Heterogeneous Method and Its Membrane Performances. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 74, 2046–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tang, M.; Liu, F.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, C. Immobilization of silver nanoparticles onto sulfonated polyethersulfone membranes as antibacterial materials. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 81, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnikrishnan, L.; Nayak, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Sarkhel, G. Polyethersulfone membranes: The effect of sulfonation on the properties. Polym.—Plast. Technol. Eng. 2010, 49, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavangar, T.; Ashtiani, F.Z.; Karimi, M. Morphological and performance evaluation of highly sulfonated polyethersulfone/polyethersulfone membrane for oil/water separation. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.; Zou, H.; Lu, D.; Gong, C.; Liu, Y. Polyethersulfone sulfonated by chlorosulfonic acid and its membrane characteristics. Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaysom, C.; Ladewig, B.P.; Lu, G.Q.M.; Wang, L. Preparation and characterization of sulfonated polyethersulfone for cation-exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 368, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Gao, J. Developing homogeneous ion exchange membranes derived from sulfonated polyethersulfone/N-phthaloyl-chitosan for improved hydrophilic and controllable porosity. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaysom, C.; Moon, S.H.; Ladewig, B.P.; Lu, G.Q.M.; Wang, L. Preparation of porous ion-exchange membranes (IEMs) and their characterizations. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 371, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, A.G.; Morales, B.A.; Cappelle, M.A.; Percival, S.J.; Small, L.J.; Spoerke, E.D.; Rempe, S.B.; Walker, W.S. Evaluation of electrodialysis desalination performance of novel bioinspired and conventional ion exchange membranes with sodium chloride feed solutions. Membranes 2021, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenina, I.; Golubenko, D.; Nikonenko, V.; Yaroslavtsev, A. Selectivity of transport processes in ion-exchange membranes: Relationship with the structure and methods for its improvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Lin, S. Membrane Design Principles for Ion-Selective Electrodialysis: An Analysis for Li/Mg Separation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3552–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.N.; Kumar, S.S.; Thanigaivelan, A.; Tarun, M.; Mohan, D. Sulfonated polyethersulfone-based membranes for metal ion removal via a hybrid process. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, A.; Madaeni, S.S.; Ghorbani, S.; Shockravi, A.; Mansourpanah, Y. The influence of sulfonated polyethersulfone (SPES) on surface nano-morphology and performance of polyethersulfone (PES) membrane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, Q.; Lu, H.; Wang, J. Modification of cation exchange membranes with conductive polyaniline for electrodialysis applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 582, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Mondal, R.; Guha, S.; Chatterjee, U.; Jewrajka, S.K. Homogeneous phase crosslinked poly(acrylonitrile-co-2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid) conetwork cation exchange membranes showing high electrochemical properties and electrodialysis performance. Polymer 2019, 180, 121680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liao, J.; Jin, W.; Luo, B.; Shen, P.; Sotto, A.; Shen, J.; Gao, C. Effect of functionality of cross-linker on sulphonated polysulfone cation exchange membranes for electrodialysis. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 138, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Pandey, R.P.; Shahi, V.K. Preparation, characterization and thermal degradation studies of bi-functional cation-exchange membranes. Desalination 2015, 367, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, G.; Pandey, R.P.; Shahi, V.K. Temperature resistant phosphorylated graphene oxide-sulphonated polyimide composite cation exchange membrane for water desalination with improved performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 520, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Xiang, Y. Effect of side chain on the electrochemical performance of poly (ether ether ketone) based anion-exchange membrane: A molecular dynamics study. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 605, 118105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, L.; Wang, J. Synthesis of cation exchange membranes based on sulfonated polyether sulfone with different sulfonation degrees. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.P.; Yadav, V.; Rajput, A.; Kulshrestha, V. Synthesis of Chloride-Free Potash Fertilized by Ionic Metathesis Using Four-Compartment Electrodialysis Salt Engineering. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6895–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.P.; Gahlot, S.; Kulshrestha, V. One Pot Synthesis of PVDF Based Copolymer Proton Conducting Membrane by Free Radical Polymerization for Electro-Chemical Energy Applications. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 520, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Shahi, V.K. Assembly of MIL-101(Cr)-sulphonated poly(ether sulfone) membrane matrix for selective electrodialytic separation of Pb2+ from mono-/bi-valent ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.P.; Gahlot, S.; Rajput, A.; Patidar, R.; Kulshrestha, V. Efficient and Cost Effective Way for the Conversion of Potassium Nitrate from Potassium Chloride Using Electrodialysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3220–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pismenskaya, N.D.; Pokhidnia, E.V.; Pourcelly, G.; Nikonenko, V.V. Can the electrochemical performance of heterogeneous ion-exchange membranes be better than that of homogeneous membranes? J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 566, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ren, L.; Chen, Q.B.; Li, P.; Wang, J. Fabrication of cation exchange membrane with excellent stabilities for electrodialysis: A study of effective sulfonation degree in ion transport mechanism. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 615, 118539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, W.; Lafi, R.; Fauvarque, J.F.; Hafiane, A.; Sollogoub, C. New ion exchange membrane derived from sulfochlorated polyether sulfone for electrodialysis desalination of brackish water. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deemer, E.M.; Xu, P.; Verduzco, R.; Walker, W.S. Challenges and opportunities for electro-driven desalination processes in sustainable applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2023, 42, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IEC (meq/g) | SD (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| PES | 1.5 | 42 |

| sPES | 2.67 | 83 |

| Sample | Membrane Material | IEC (meq/g) | CE (%) | Salt Removal (%) | Feed Solution (mol/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDP-2.0 | PPTA/DS/PPTA | 1.6 | - | 95.1 | 0.08 Na2SO4 | [10] |

| 60SPSF-C2 | SPSF/Acrylic crosslinker | 1.6 | 95.7 | 91.7 | 0.1 NaCl | [11] |

| Z-2 | Zn-MOF/sPES | - | 75.8 | 94.1 | 0.1 NaCl | [12] |

| SPEEK/PGO-8 | SPPEK/PGO | 2.16 | 78.2 | 67.6 | 0.7 NaCl | [13] |

| Sub-nanoporous PES | PES | - | - | - | 0.1 LiCl, NaCl, KCl, MgCl2 | [14] |

| SPSU-60 | SPSF/AgNP | 1.55 | 96.9 | 67.5 | 0.5 NaCl | [15] |

| SG-10 | sPES/GO | 1.27 | 97.4 | 99.1 | 0.1 NaCl | [16] |

| 40% sPES-PES | sPES/PES/PVP | 0.52 | 127.5 | 91.9 | 0.1 NaCl | [17] |

| S/P/PANi-0.6 | sPES/PVP/PANi | 0.47 | 94.3 | - | 0.1 NaCl | [31] |

| PAN-PAMPS-2 | PAN/PAMPS | 1.65 | 91 | - | 0.35 NaCl | [32] |

| DES-5 | sPES/S-MoS2 | 1.42 | 69.5 | - | 0.1 NaCl | [33] |

| PVA/BFC-70 | PVA/DVB/AMPS | 1.3 | 87.5 | - | 0.85 NaCl | [34] |

| SPI/PGO-8 | SPI/PGO | 2.37 | 76.4 | - | 0.1 NaCl | [35] |

| SPK/IGO-8 | SPEEK/IGO | 2.23 | 82.9 | - | 0.85 NaCl | [36] |

| SGO-5 | sPES/SGO | 1.7 | 93.1 | - | 0.1 NaCl | [37] |

| S-25/P | sPES/PVP | 0.65 | - | - | 0.1 NaCl | [38] |

| 70% S-PVDF | SPVDF/PVDF | 0.7 | - | - | 0.1 NaCl | [39] |

| MIL-10 | sPES/MIL-101 | 1.04 | 85 | - | 0.1 NaCl | [40] |

| PM-5 | PVC/St/DVB/SGO | 1.76 | 82.3 | - | 0.085 NaCl | [41] |

| CEM-3 | PAN/PStSO3Na/PnBA | 1.47 | 76.8 | - | 0.085 NaCl | [42] |

| S/P K30 | sPES/PVP | 0.54 | 80 | 90 | 0.86 NaCl | [43] |

| ClNH2 | Cl-PES/NH2-PES | 2.2 | - | 93.8 | 0.05 NaCl | [44] |

| PES | PES | 1.5 | 50 | 24 | 0.05 NaCl | (This work) |

| sPES | sPES | 2.67 | 48 | 33 | 0.05 NaCl | (This work) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Deemer, E.M.; Li, X.; Walker, W.S. Sulfonated Polyethersulfone Membranes for Brackish Water Desalination: Fabrication, Characterization, and Electrodialysis Performance Evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010216

Chen L, Deemer EM, Li X, Walker WS. Sulfonated Polyethersulfone Membranes for Brackish Water Desalination: Fabrication, Characterization, and Electrodialysis Performance Evaluation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(1):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010216

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Li, Eva M. Deemer, XiuJun Li, and W. Shane Walker. 2025. "Sulfonated Polyethersulfone Membranes for Brackish Water Desalination: Fabrication, Characterization, and Electrodialysis Performance Evaluation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 1: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010216

APA StyleChen, L., Deemer, E. M., Li, X., & Walker, W. S. (2025). Sulfonated Polyethersulfone Membranes for Brackish Water Desalination: Fabrication, Characterization, and Electrodialysis Performance Evaluation. Applied Sciences, 15(1), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010216