Calculation Method for Settlement Deformation of Existing Tunnel Induced by Underpass Construction

Abstract

1. Introduction

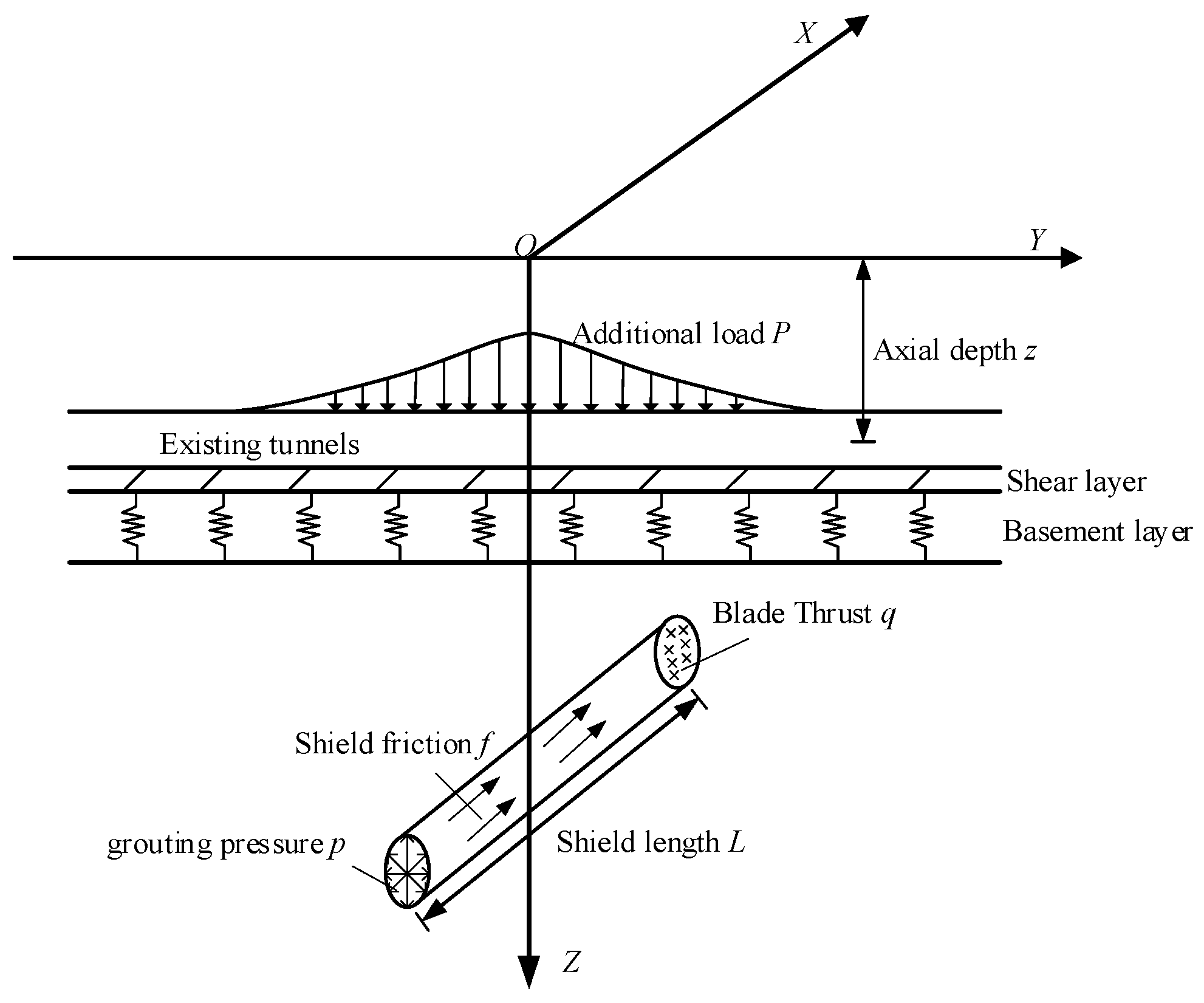

2. Settlement Calculations for Existing Tunnels

2.1. Model Assumptions

2.2. Energy Method

3. Calculation of Additional Stresses in Tunnel Undercutting

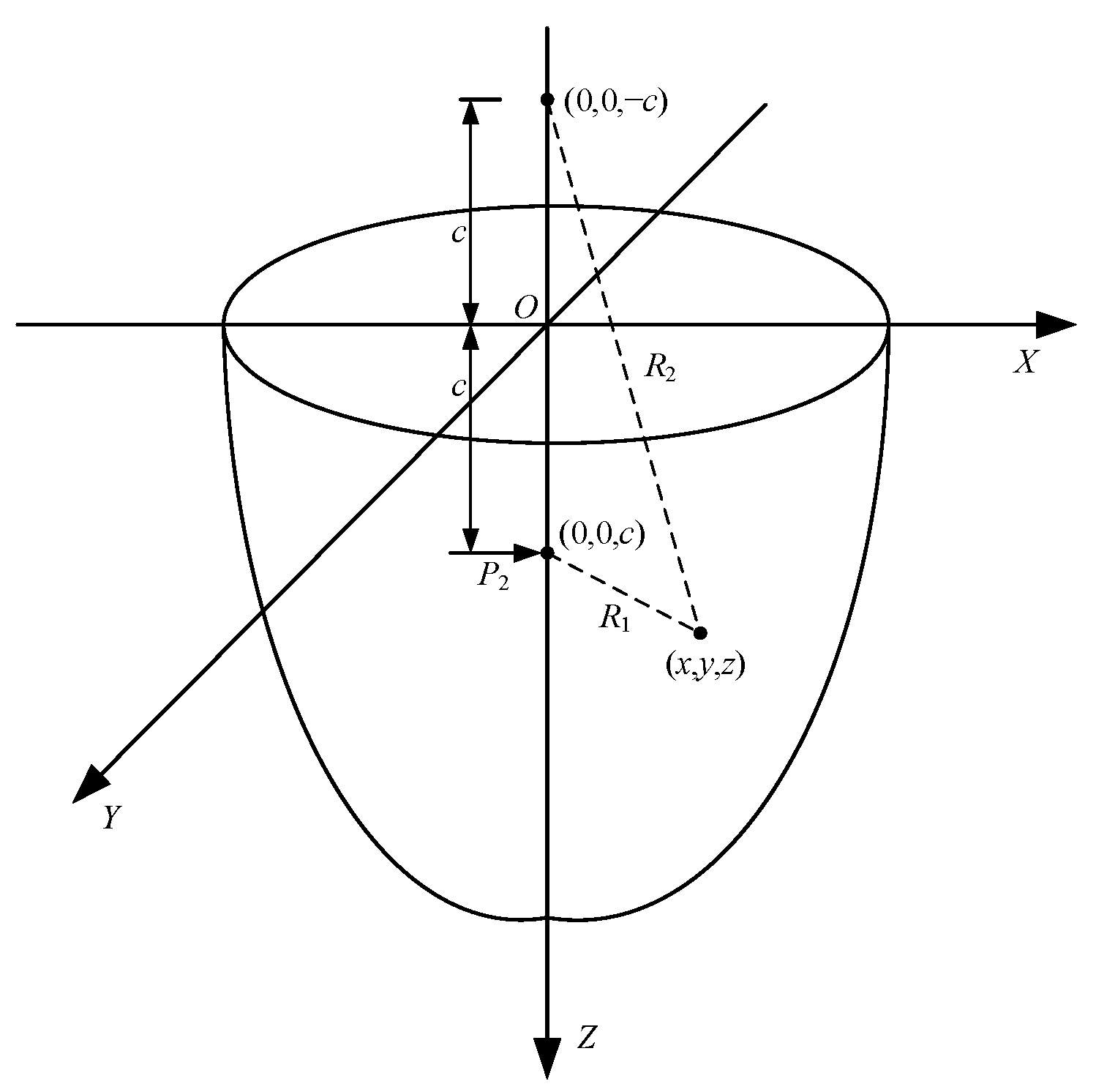

3.1. Mindlin’s Solution for Additional Stresses

3.2. Additional Stresses Caused by Shield Cutter Thrusts

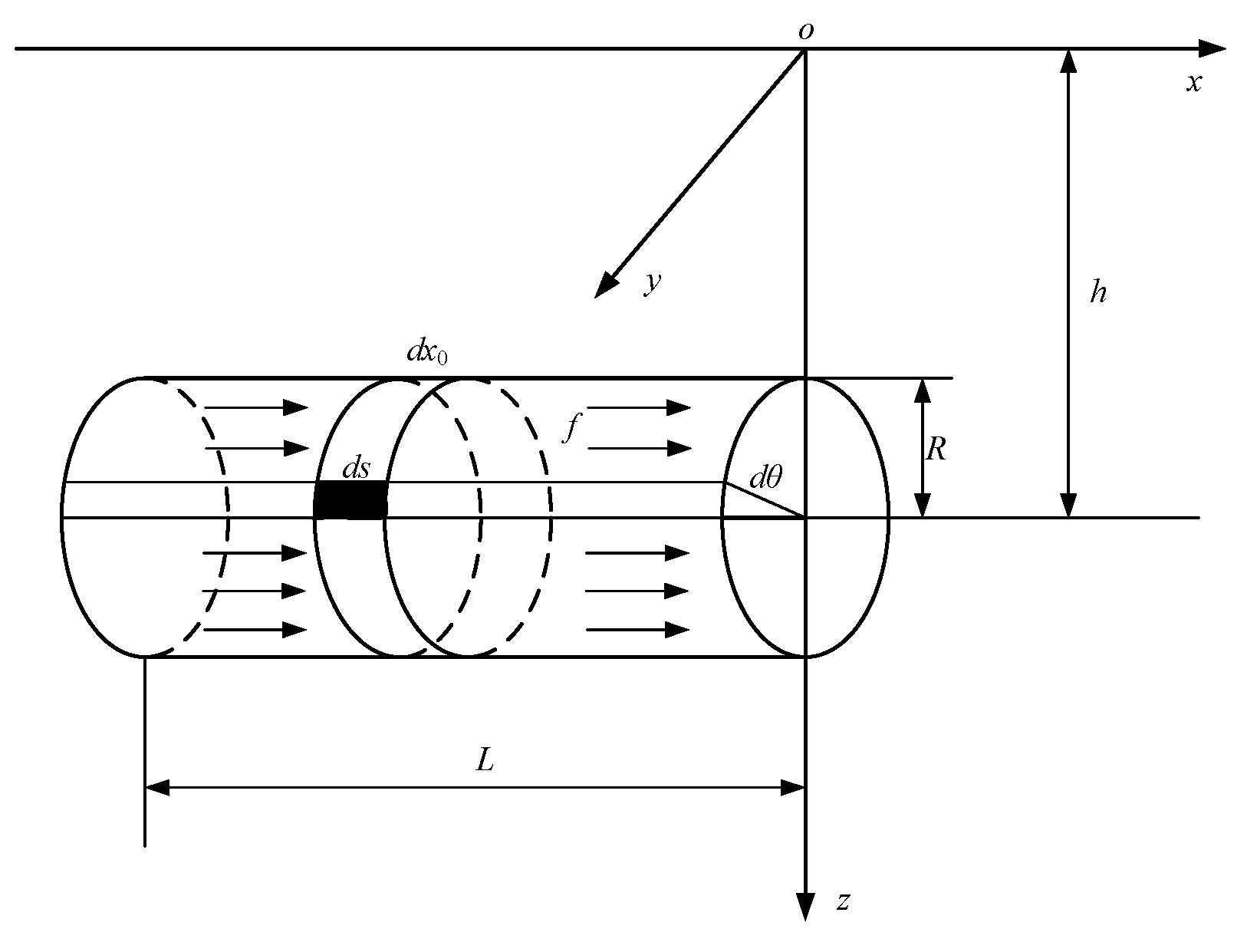

3.3. Additional Stress Caused by Shield Shell Friction

3.4. Additional Stress Caused by Grouting Pressure

3.5. Additional Stresses due to Strata Loss

3.6. Calculation Flow Chart

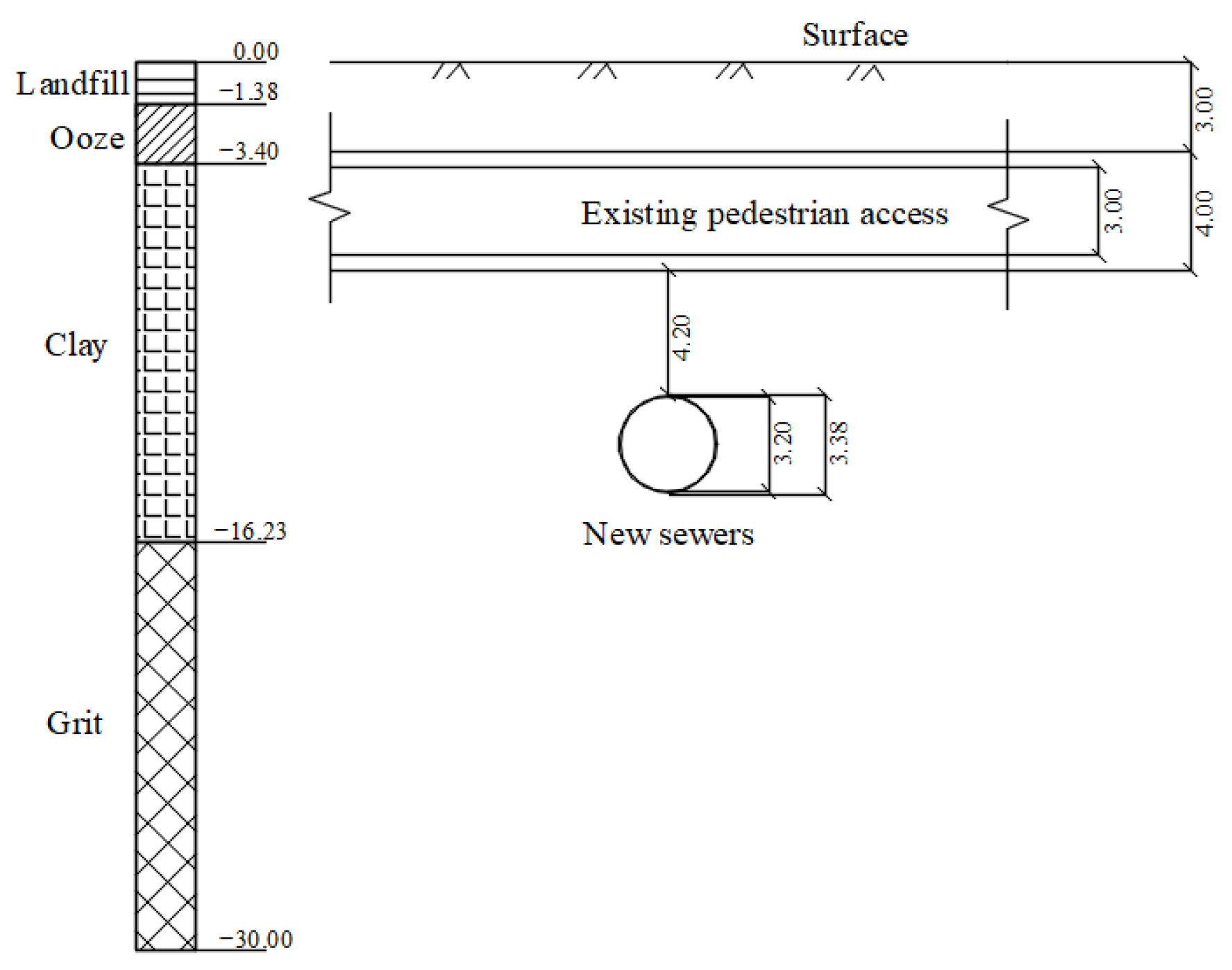

4. Engineering Case Comparison

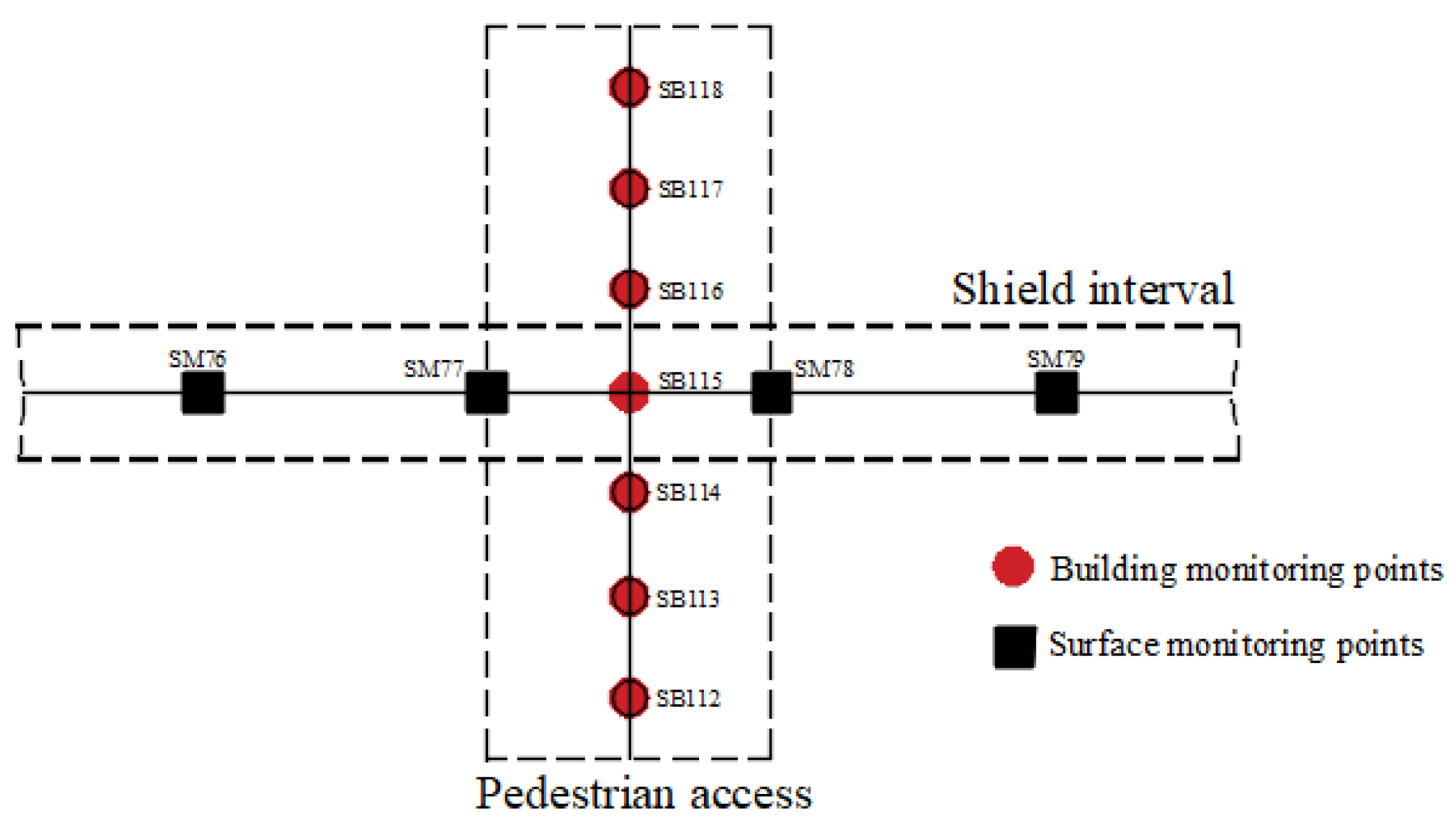

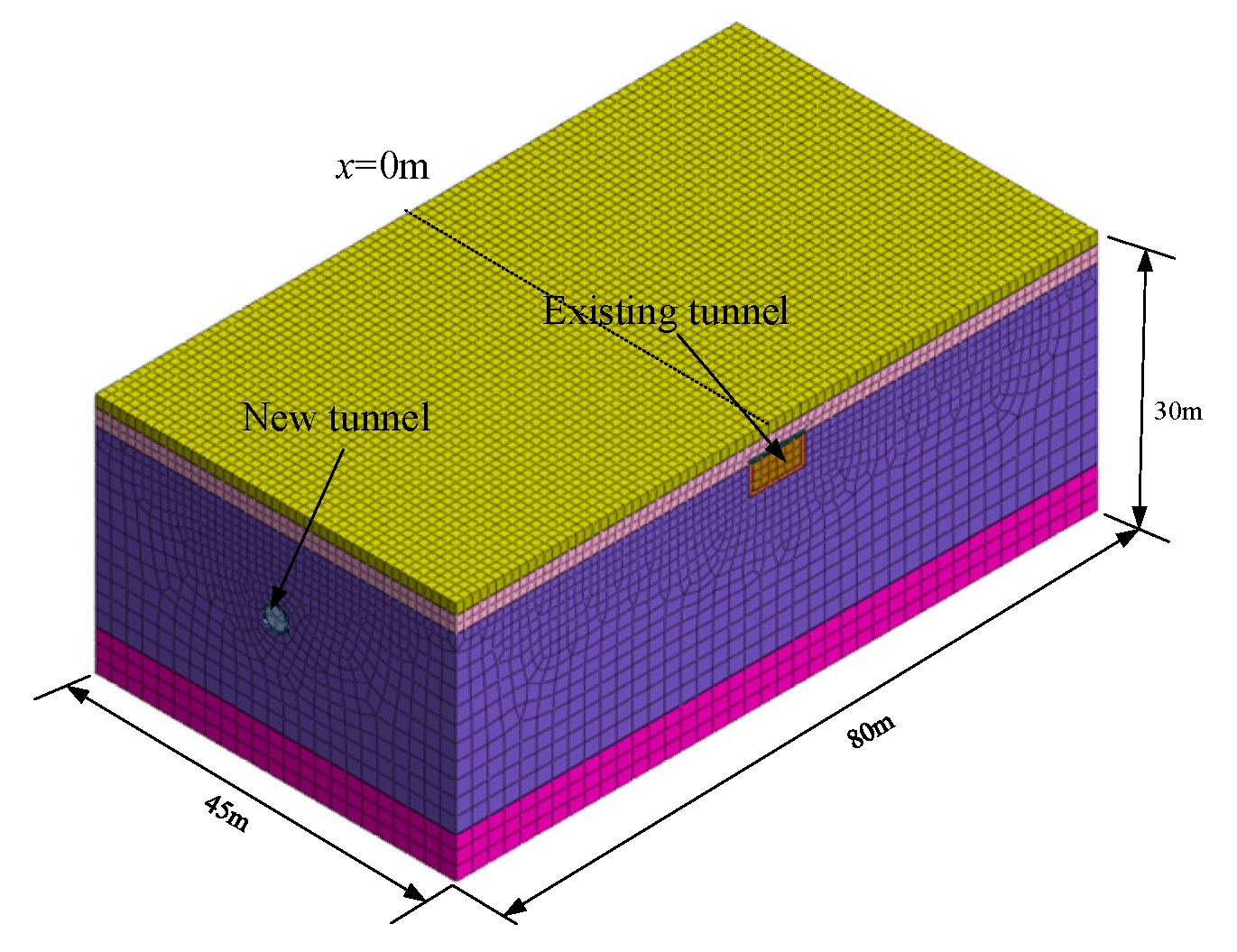

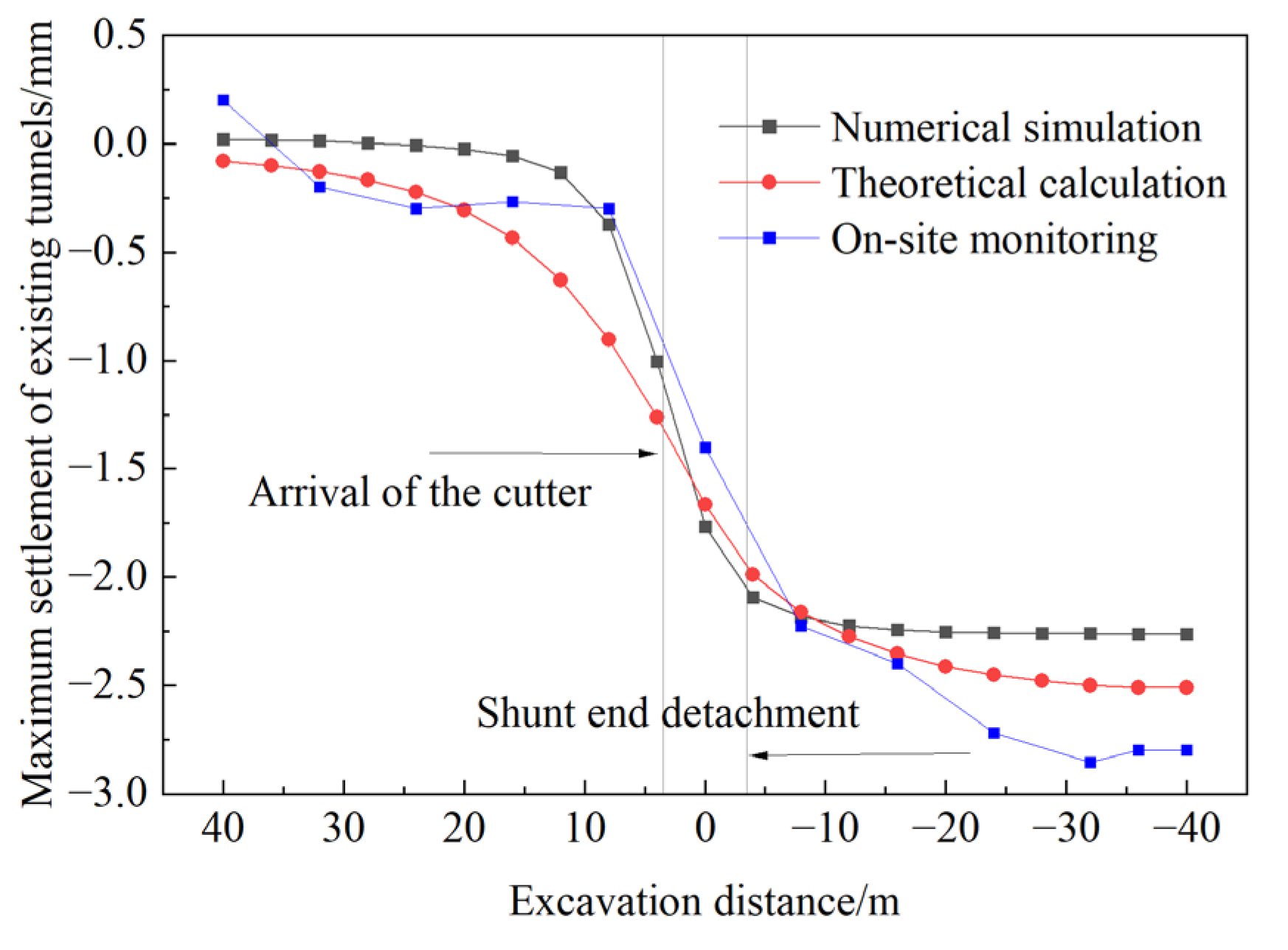

4.1. Engineering Measurements and Numerical Simulations

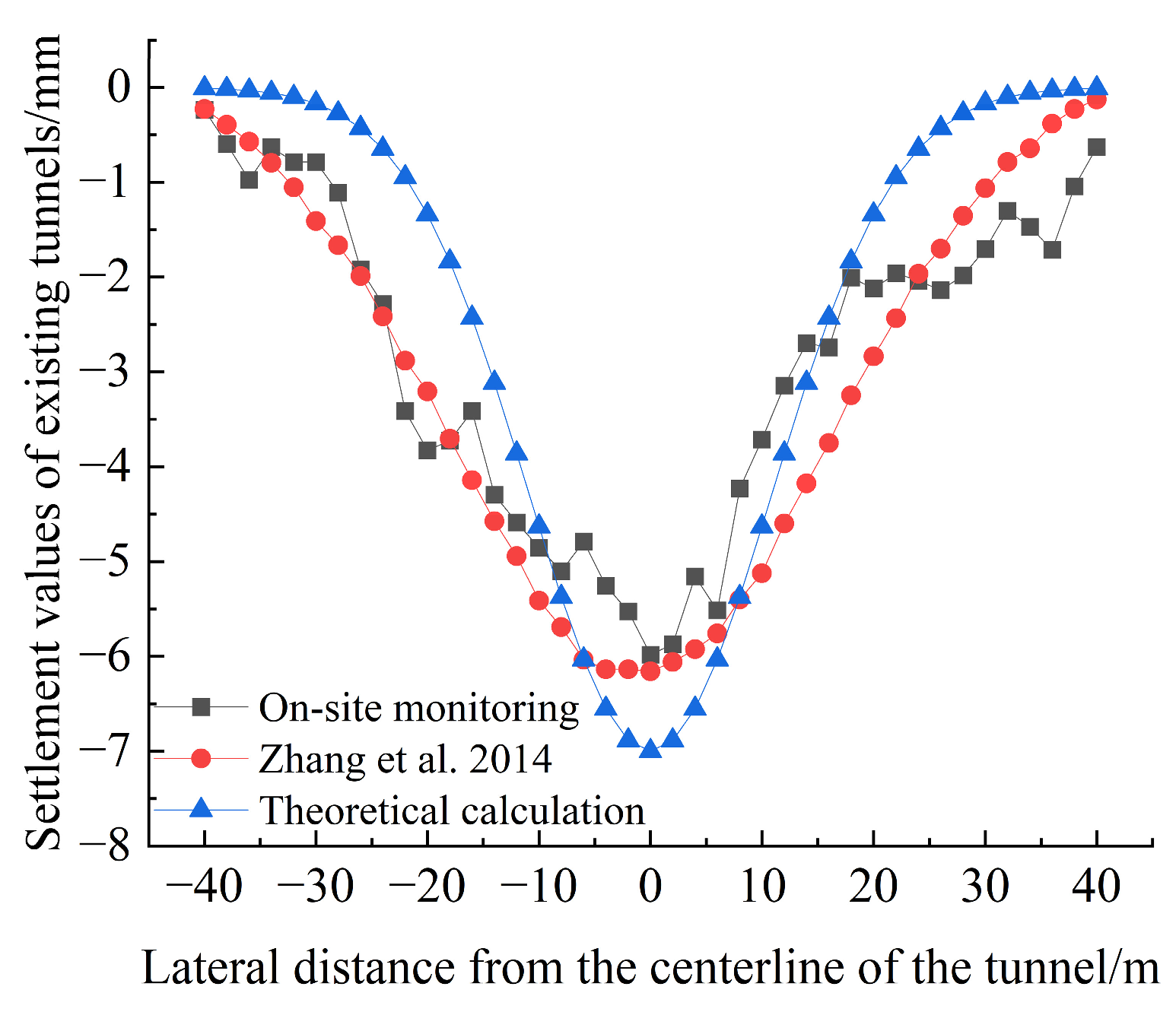

4.2. Engineering Case 2

5. Analysis of Influencing Factors

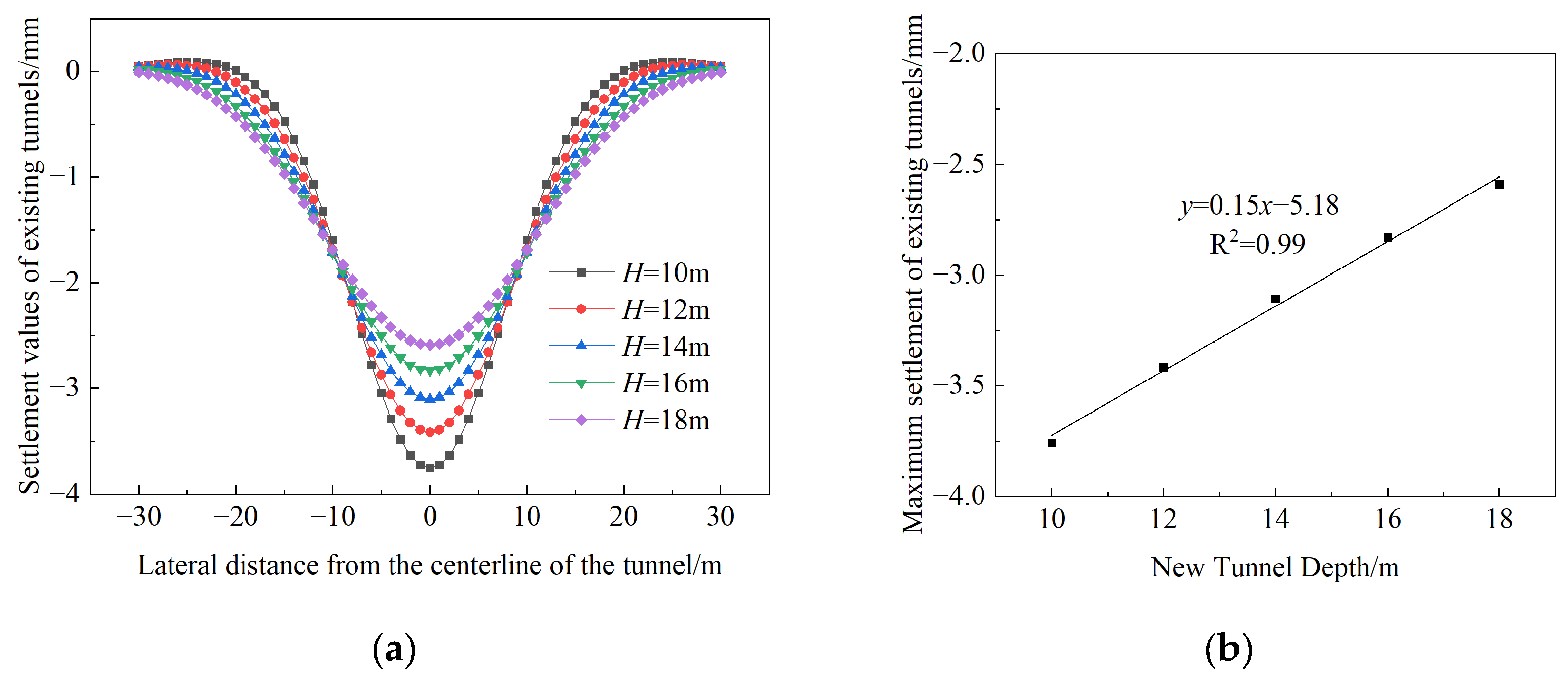

5.1. New Tunnel Depth

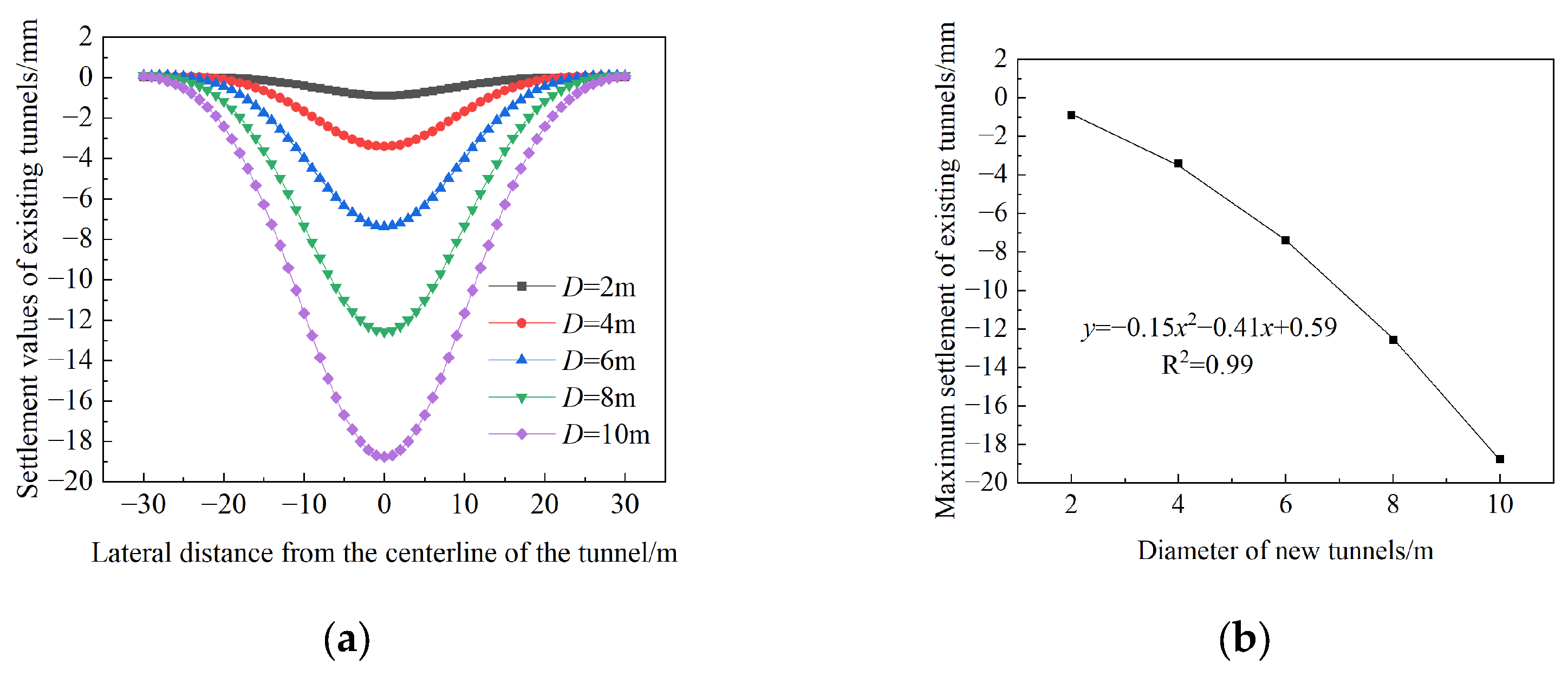

5.2. New Tunnel Diameter

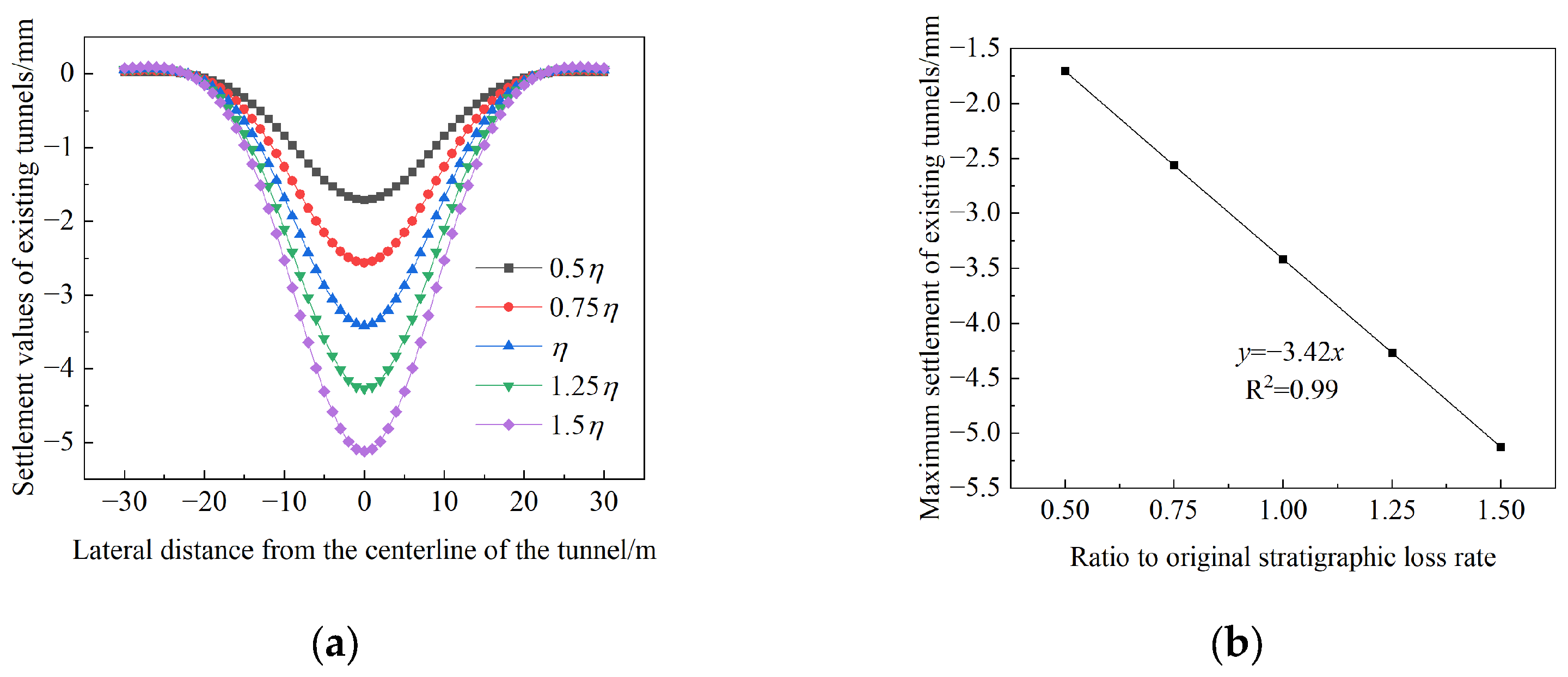

5.3. Stratigraphic Loss Rate

6. Engineering Optimization Recommendations

6.1. Analysis Method

6.2. Optimization Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, J.W.; Hao, S.; Cui, W.; Li, M.Y. Investigation of Underpass and Railway Track Settlements Induced by Shield Tunneling Through In Situ Test and 3D FEM Simulation. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 21, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pei, X.K.; Yang, C.; Zhu, B.Z. Dynamic response analysis of the process of the utility shield tunnel under-passing the operating subway tunnel. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 2023, 23, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Lu, S.D.; Yang, G.L.; Zhang, P.R.; Shuai, J.G.; Fu, X. Field experimental study on construction mechanical characteristics of shallow buried biased pressure multi-cavity tunnel portal section. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 54, 4720–4731. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Long, Y.H.; Ou, X.D.; Xing, X.W.; Zhang, T. Settlement analysis of existing tunnels caused by underpass construction of shield tunnel for new curved subway. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2023, 55, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhou, K.; Wei, J.; Liu, X.C.; Lin, Y.L.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Q. Analysis on the excavation influence of triangular-distribution tunnels for the wind pavilion group of a metro station. J. Cent. South Univ. 2020, 27, 3852–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.H.; Zhang, D.B.; Lian, C.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Yin, H.D. Study on the influence of an under-crossing parallel double-line shield tunnel on the existing tunnel structure. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.L.; Yu, J.L.; Gong, X.N.; Zhu, M. Characteristics and countermeasures of tunnel heave due to large-diameter shield tunneling underneath. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2020, 34, 04019081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.L.; Yu, H.F.; Niu, H.S.; Hu, J.B.; Han, W.W.; Huang, X.M. Interactive effects of crossing tunnel construction on existing tunnel: Three-dimensional centrifugal test and numerical analyses. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 35, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Lin, L.Q.; Xu, J.N.; Qin, J.J. Mechanical analysis of expansion soil tunnel construction under humidified condition with close penetration of existing subway station. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.P.; Zheng, H.W.; He, Q.M.; Liu, H.Y. Research on optimization of construction parameters of shield tunnel construction with small angle slanting down through existing tunnel in sandy soil stratum. China J. Highw. 2018, 31, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Lei, S.X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Fang, Z.C.; Wang, C.; Xu, S. Improved stochastic medium theory model for prediction of deformation of existing tunnels and strata caused by tunnel underpass construction. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, R.Z.; Zong, M.F.; Kang, C.; Wu, W.B.; Fan, Y.X.; Xia, T.D.; Cheng, K. Longitudinal impact of tunnel underpass on existing shield tunnel considering tunnel shear effect. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2018, 52, 420–430+472. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, D.L. Mechanical responses of existing tunnel due to new tunnelling below without clearance. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 80, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.L.; Yu, J.L.; Gong, X.N.; Zhu, M.; Cheng, K. Study on the impact of new double-lane tunnels on existing shield tunnels. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 3586–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Z.G.; Wei, G.; Wu, Z.T.; Lu, Z. Analysis of longitudinal deformation of existing discontinuous tunnel induced by shield penetration based on Kerr foundation model. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Q.; Liang, F.Y.; Zhang, H.; Chu, F. Energy variational analysis method for vertical displacement of underground pipeline caused by tunnel crossing. Rock Soil Mech. 2014, 35, 217–222+231. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Cui, C.H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.H. Calculation of pipeline settlement caused by double-circle shield construction based on energy method. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2019, 15, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.Y.; Luo, W.J.; Yan, J.W.; Jiang, X.H. Settlement study of twin-lane underpass existing tunnels based on energy method. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2024, 56, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, I.E.; Morfidis, K. Bending of beams on three-parameter elastic foundation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, C.R.; Huang, M.S. Foundation modulus of buried pipelines under passive condition. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Study on Longitudinal Settlement of Shield Tunnel in Soft Soil; Tongji University: Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Bian, X.W.; Peng, H.; Zhu, B.Q.; Zhou, Y.L. Additional Stress of Soil and Surface Settlement during Tunnel Shield Construction. Buildings 2023, 13, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindlin, R.D. Force at a point in the interior of a semi-infinite solid. Physics 1936, 7, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X. Soil-pressure balance shield cutter plate crowding effect and cutter plate opening rate on shield frontal contact pressure. J. Civ. Eng. 2009, 42, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.H.; Xu, Q.W.; Liao, S.M.; Yu, N.; Fu, D.M.; Wu, X.S. Experimental study on jacking thrust modeling for soil-pressure balance shield construction. Geotech. Mech. 2007, 28, 1587–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Z.; Dai, X.Y.; Sun, K.; Ai, G.P.; Lei, T. Calculation method of longitudinal deformation of metro shield tunnel overpassing existing line at short distance. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 831–842. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.J. Analysis of Soil Deformation Caused by Shield Tunneling; Zhejiang University: Hangzhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Huang, M.S.; Xu, C.; Jiang, Y.J.; Wang, W.D. Simplified solution for tunnel-soil-pile interaction in Pasternak’s foundation model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 78, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.M.; Zong, X.; Huang, H.W. Study on longitudinal deformation of built tunnel above caused by shield tunnel boring. Geotechnics 2014, 35, 2659–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Analysis of surface settlement and its sensitivity caused by shield construction of a two-lane tunnel under soft ground. Build. Struct. 2021, 51, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, T.; Huang, F.; Li, S.; Ouyang, T.Y.; Ying, J.; Zhao, H.R. Optimization of pre-grouting construction and evaluation of grouting effect in a deeply buried silt-filled shield tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Type | Ontological Relationship | Thicknesses/m | Modulus of Compression/MPa | Capacity/(kN/m2) | Cohesive Force/kPa | Angle of Internal Friction/° | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| landfill | Mohr-Coulomb | 1.38 | 9 | 19 | 10 | 28 | 0.25 |

| ooze | Mohr-Coulomb | 2.02 | 2 | 16.5 | 7.5 | 25 | 0.32 |

| silty clay | Mohr-Coulomb | 21.6 | 7.5 | 19.1 | 14 | 26 | 0.35 |

| grit | Mohr-Coulomb | 5 | 20 | 20 | 26 | 31.5 | 0.28 |

| shield | elastic | 0.09 | 2.1 × 105 | 78 | - | - | 0.3 |

| Lining Pipe Sheets | elastic | 0.2 | 2.88 × 104 | 25 | - | - | 0.2 |

| Grouting (before hardening) | elastic | 0.1 | 1 | 22 | - | - | 0.28 |

| Grouting (after hardening) | elastic | 0.1 | 100 | 22 | - | - | 0.25 |

| Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| New Tunnel Depth | 12 | 0.53 | |

| Diameter of new tunnels | 4 | 1.87 | |

| Stratigraphic loss rate | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J.-H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Yang, G.-L. Calculation Method for Settlement Deformation of Existing Tunnel Induced by Underpass Construction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052430

Cao L, Zhang J, Xie J-H, Lin Y-L, Yang G-L. Calculation Method for Settlement Deformation of Existing Tunnel Induced by Underpass Construction. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(5):2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052430

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Lan, Jie Zhang, Jia-Hua Xie, Yu-Liang Lin, and Guo-Lin Yang. 2025. "Calculation Method for Settlement Deformation of Existing Tunnel Induced by Underpass Construction" Applied Sciences 15, no. 5: 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052430

APA StyleCao, L., Zhang, J., Xie, J.-H., Lin, Y.-L., & Yang, G.-L. (2025). Calculation Method for Settlement Deformation of Existing Tunnel Induced by Underpass Construction. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052430