Finite Element Analysis of the Contact Pressure for Human–Seat Interaction with an Inserted Pneumatic Spring

Abstract

:1. Introduction

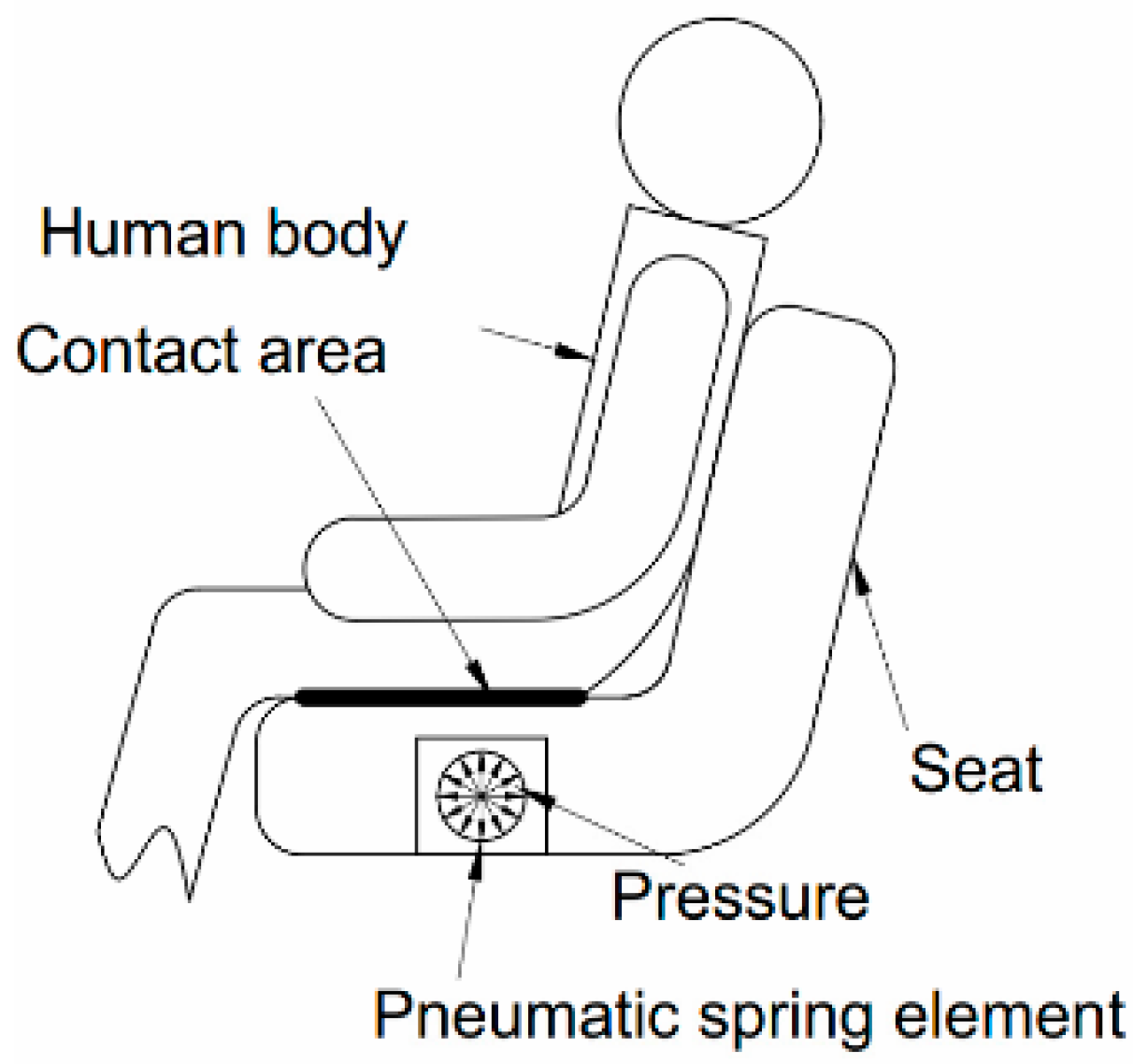

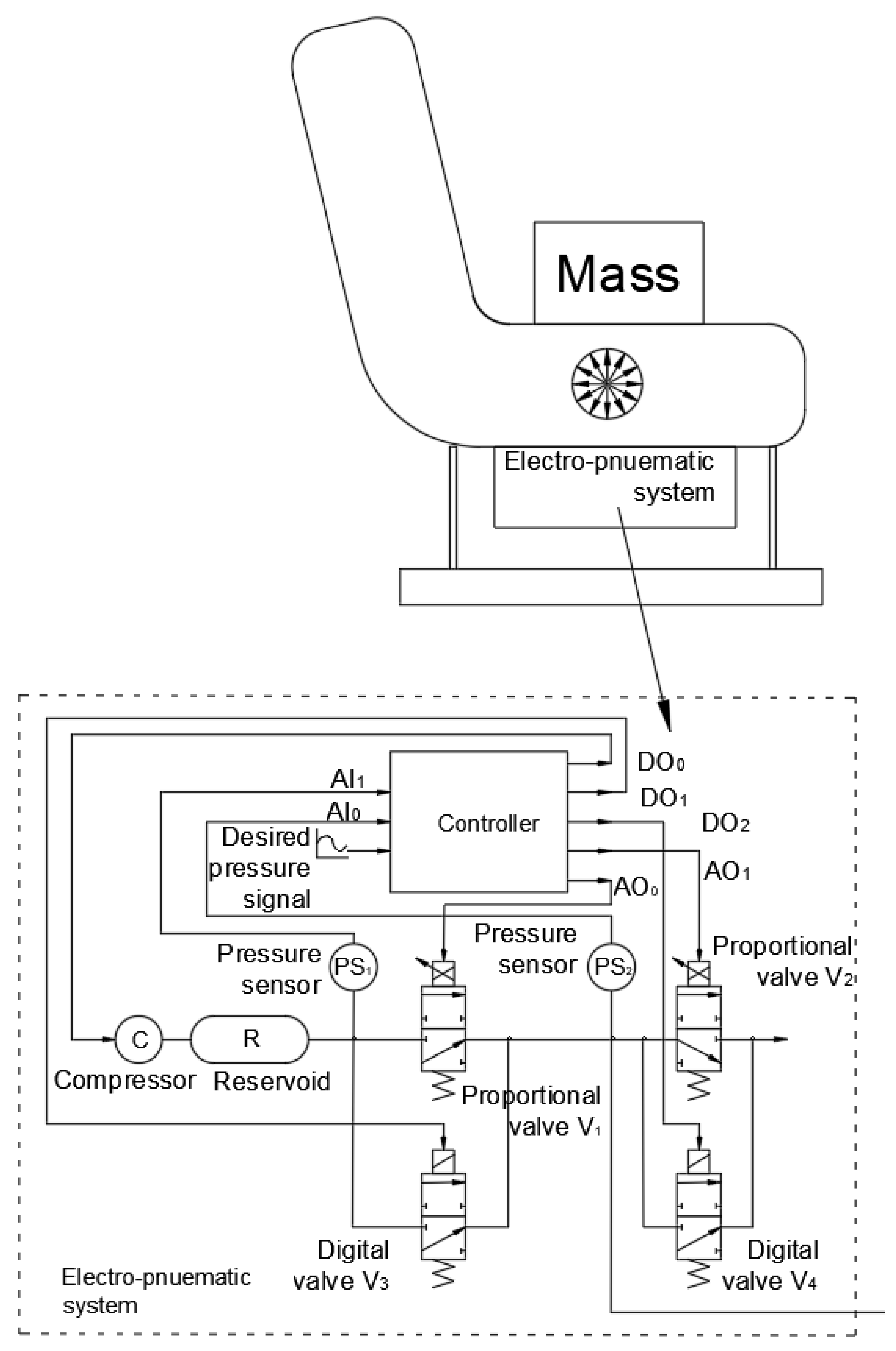

2. Preview of the Car-Seat Model with an Integrated Pneumatic Spring Device

2.1. Design and Integration of the Pneumatic Spring

2.2. Functionality of the Pneumatic Spring

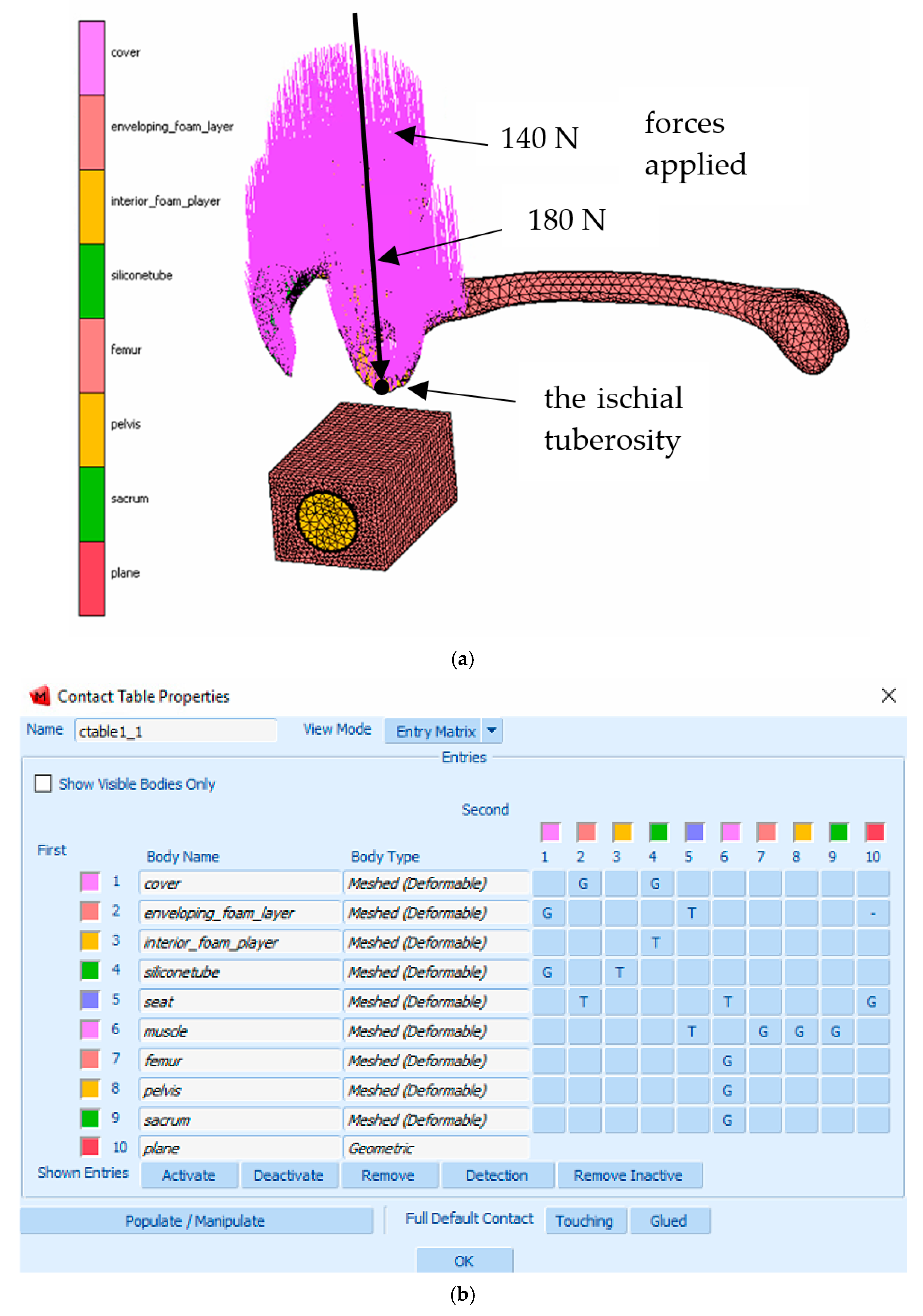

3. Finite Element Modeling (FEM) of Human–Seat Interactions

3.1. Human Modeling

| Young’s Modulus (E/MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio (µ) | Density (ρ/kg.m3) |

|---|---|---|

| 16,700 | 0.3 | 1700 |

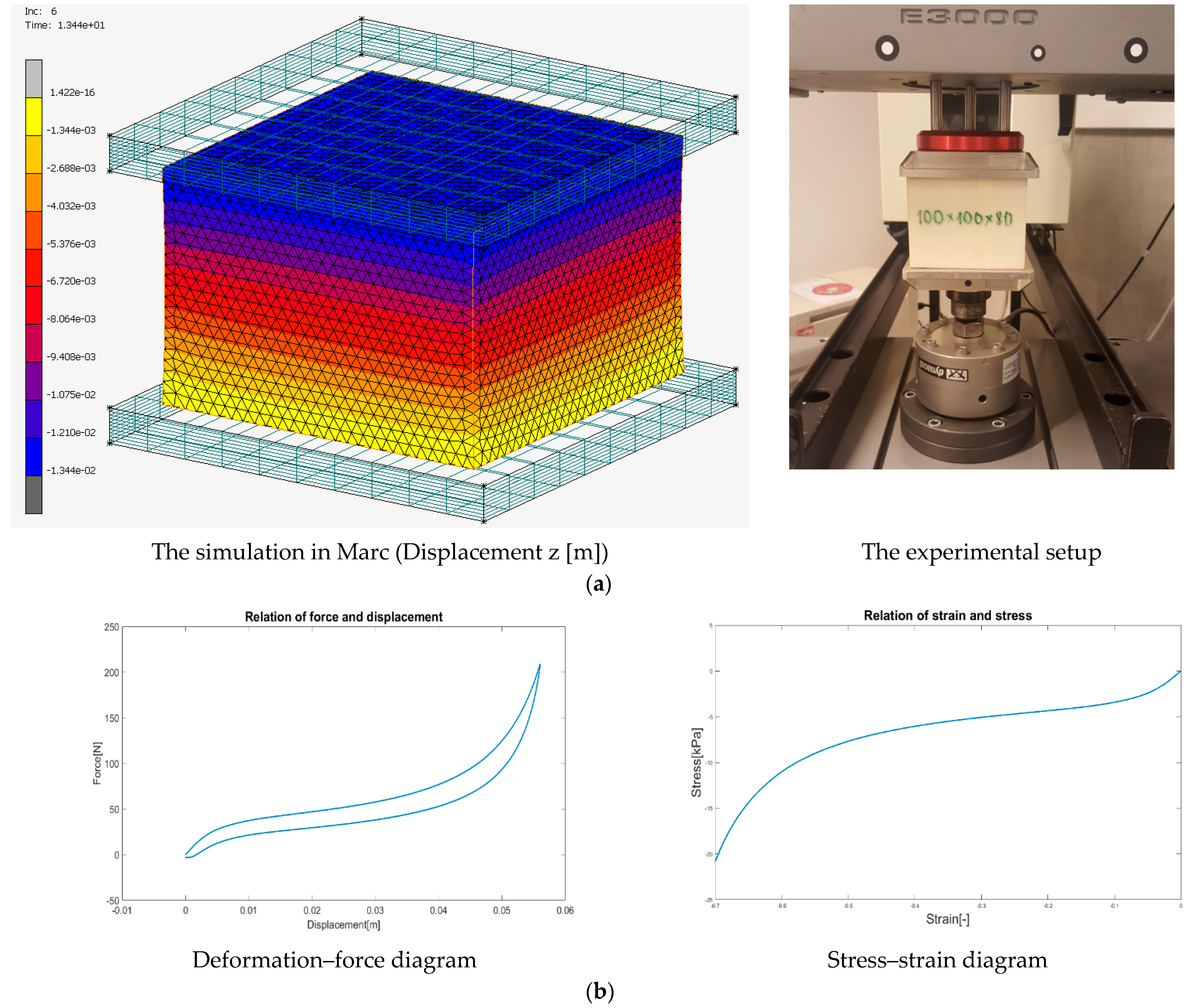

3.2. Seat Cushion Modeling

3.3. Material Modeling and Challenges

3.3.1. Hyperelastic Modeling of Polyurethane Foam

3.3.2. Viscoelasticity of the Polyurethane Foam

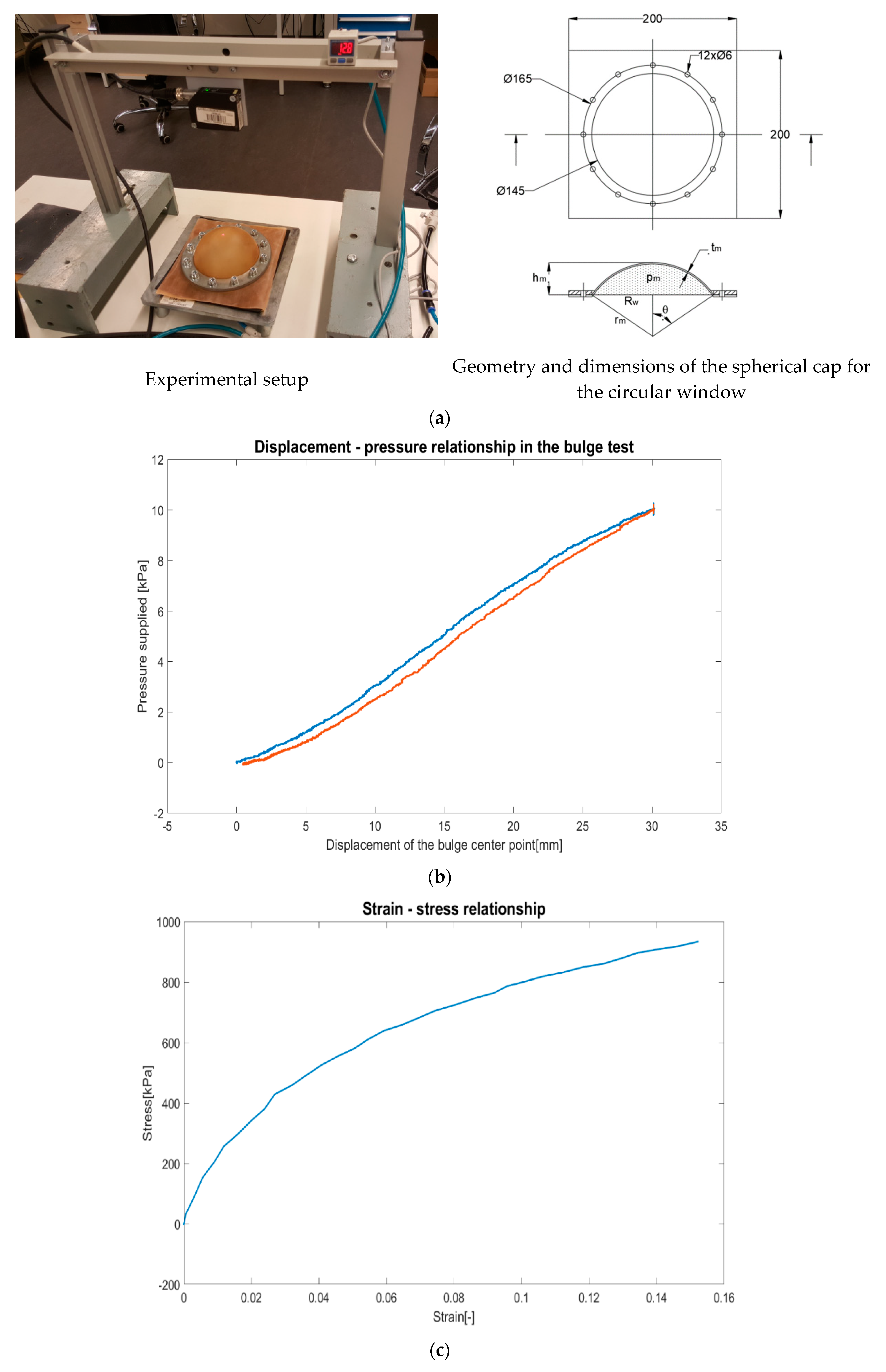

3.3.3. Material Modeling for Latex and Fabric Adhesive Tape

- Material Characterization of Latex Using Circular Membrane Inflation Test

- b.

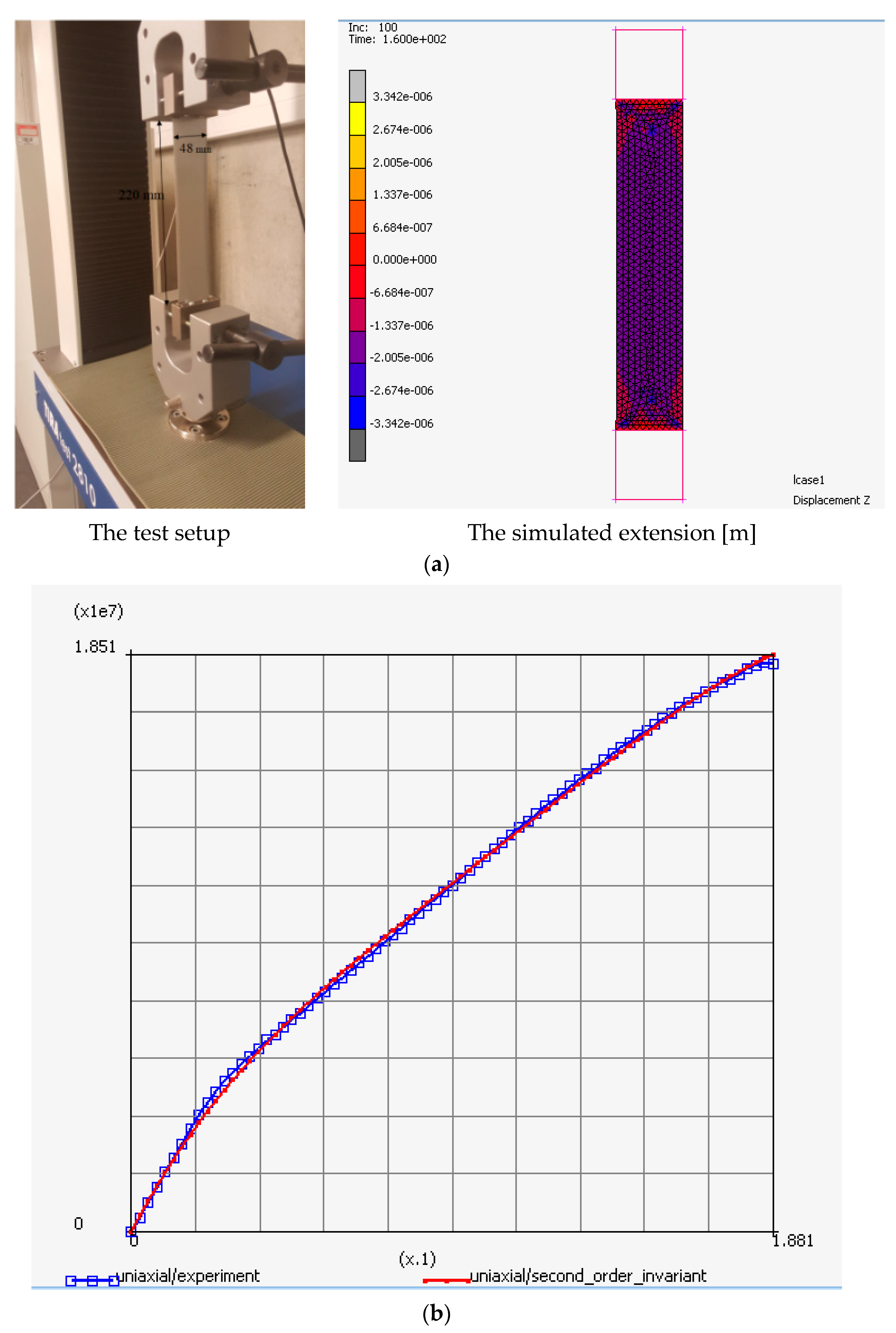

- Material Characterization of Fabric Adhesive Tape Using Uniaxial Tensile Test

3.4. Boundary Conditions and Initial Setup for Simulation

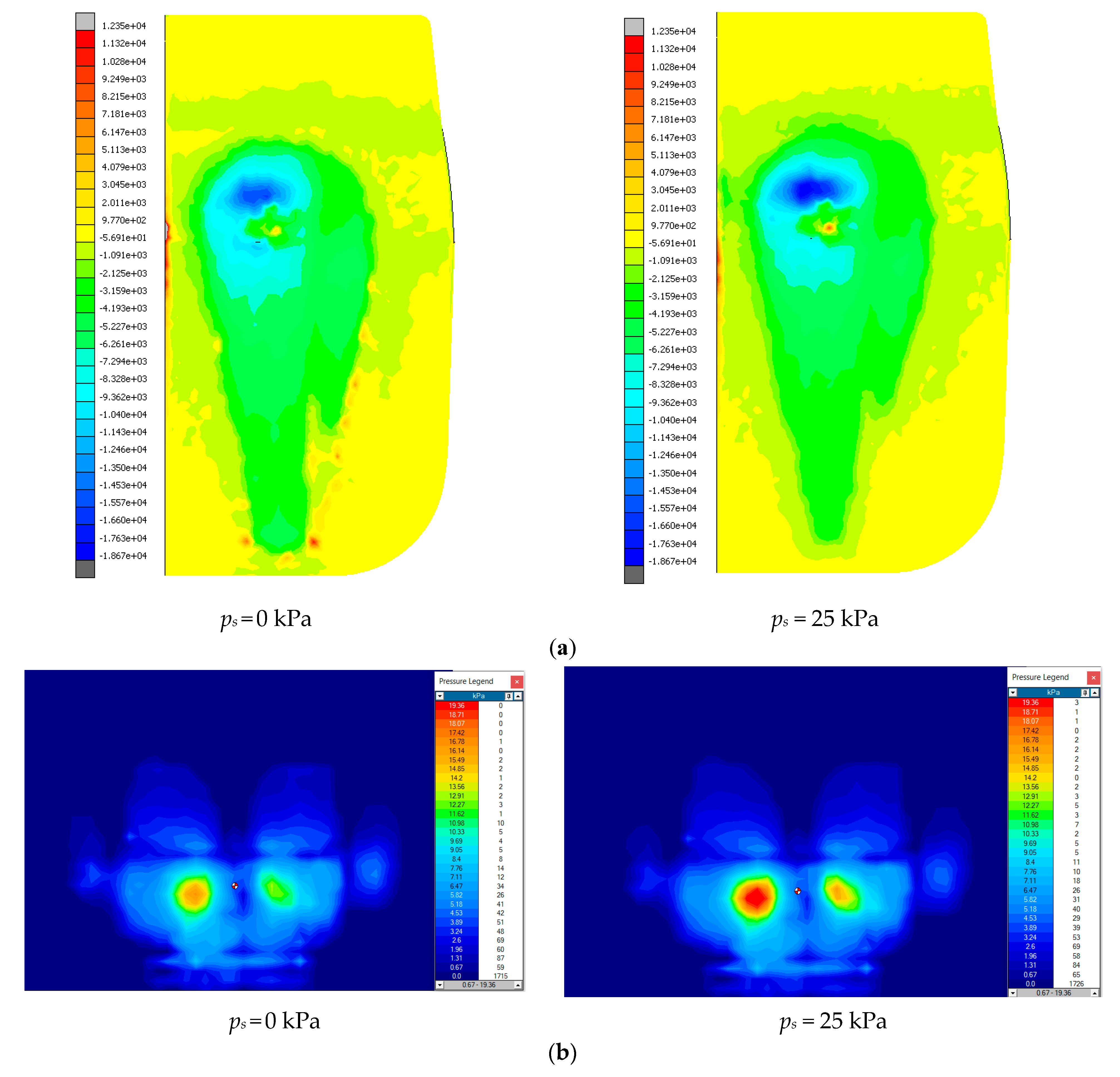

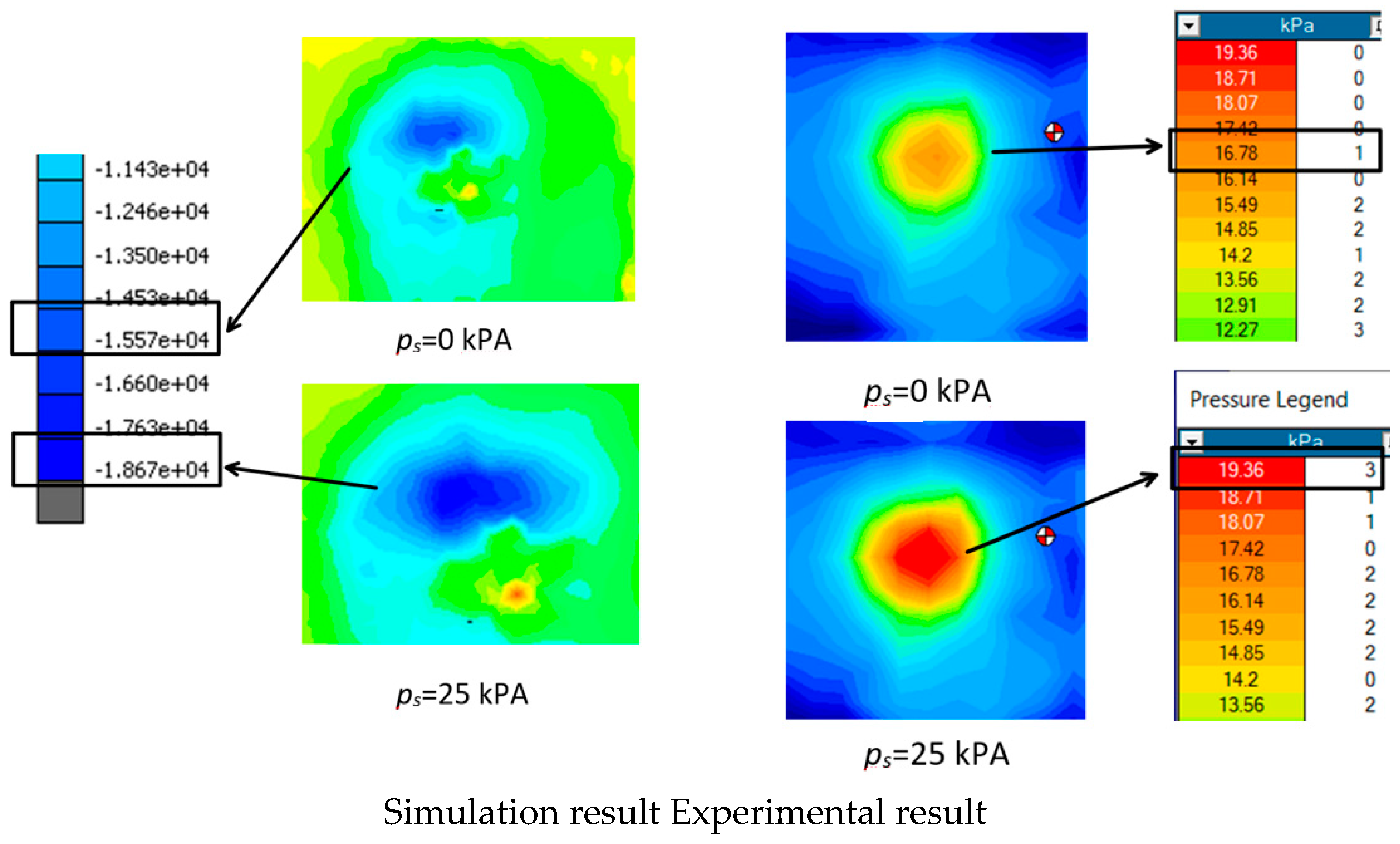

4. Simulation and Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mergl, C.; Klendauer, M.; Mangen, C.; Bubb, H. Predicting Long Term Riding Comfort in Cars by Contact Forces Between Human and Seat; SAE Technical Paper 2005-01-2690; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, G.; Nussbaum, M.A. Driver sitting comfort and discomfort (part II): Relationships with and prediction from interface pressure. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2008, 38, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirkl, D.; Xuan, T.T. Simulation model of seat with implemented pneumatic spring. Vibroengineering Procedia 2016, 7, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, T.T.; Cirkl, D. FEM model of pneumatic spring assembly. Vibroengineering Procedia 2017, 13, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.T.; Cirkl, D. Modelling of dynamical behavior of pneumatic spring—Mass system. Eng. Mech. 2018, 2018, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.T.; Cirkl, D. The effect of system improvement on regulation of pressure inside pneumatic spring element and on transmission of acceleration. Vibroengineering Procedia 2019, 27, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.T.; Phu, D.N. The mathematical model of the improved system of the seat with adjustable pressure profile. Math. Model. Eng. 2020, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyen, T.-T.; Nguyen, D.-T. Improving parameters for achieving uniform cylindrical cup wall thickness in two-step deep drawing processes with SPCC sheet material. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 09544089241285182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, Q.-H.; Luyen, T.-T.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Bui, N.-T. A Study on Yield Criteria Influence on Anisotropic Behavior and Fracture Prediction in Deep Drawing SECC Steel Cylindrical Cups. Materials 2024, 17, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyen, T.T.; Mac, T.B.; Banh, T.L.; Nguyen, D.-T. Investigating the impact of yield criteria and process parameters on fracture height of cylindrical cups in the deep drawing process of SPCC sheet steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 2059–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.-H.-L.; Luyen, T.-T.; Nguyen, D.-T. A Study Utilizing Numerical Simulation and Experimental Analysis to Predict and Optimize Flange-Forming Force in Open-Die Forging of C45 Billet Tubes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyen, T.T.; Nguyen, D.T. Improved uniformity in cylindrical cup wall thickness at elevated temperatures using deep drawing process for SPCC sheet steel. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawneh, O.; Zhong, X.; Faieghi, R.; Xi, F. Finite Element Methods for Modeling the Pressure Distribution in Human Body–Seat Interactions: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.P.; Manary, M.A.; Schneider, L.W. Methods for Measuring and Representing Automobile Occupant Posture; SAE Technical Paper no. 724; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.P.; Manary, M.A.; Flannagan, C.A.C.; Schneider, L.W. A statistical method for predicting automobile driving posture. Hum. Factors 2002, 44, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankoke, S.; Siefert, A. Virtual Simulation of Static and Dynamic Seating Comfort in the Development Process of Automobiles and Automotive Seats: Application of Finite-Element-Occupant-Model CASIMIR; SAE Technical Paper no. 724; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefert, A.; Pankoke, S.; Hofmann, J. CASIMIR/Automotive: A Software for the Virtual Assessment of Static and Dynamic Seating Comfort; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2009; Volume 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Van Markwijk, R.; Verver, M.; Furtado, R.; Pewinski, W. Numerical Prediction of Seating Position in Car Seats; SAE Technical Paper no. 724; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Ren, J.; Sang, C.; Li, L. Simulation of the interaction between driver and seat. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2013, 26, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujicic, M.; Pandurangan, B.; Arakere, G.; Bell, W.C.; He, T.; Xie, X. Seat-cushion and soft-tissue material modeling and a finite element investigation of the seating comfort for passenger-vehicle occupants. Mater. Des. 2009, 30, 4273–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wen, H.; Ni, X.; Zhuang, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H. Optimization Study on the Comfort of Human-Seat Coupling System in the Cab of Construction Machinery. Machines 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MTanzi, C.; Farè, S.; Candiani, G. Mechanical Properties of Materials. In Foundations of Biomaterials Engineering; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassi, F.; Pantalé, O.; Zghal, A.; Rakotomalala, R. Analysis of the thinning phenomenon variations in sheet metal forming process. In Proceedings of the IX International Conference on Computational Plasticity, COMPLAS IX, Barcelone, Spain, 5–7 September 2007; pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Eriksson, A. Contact mechanics of a circular membrane inflated against a deformable substrate. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2015, 67–68, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volinsky, A.A.; Bahr, D.F.; Kriese, M.D.; Moody, N.R.; Gerberich, W. Nanoindentation Methods in Interfacial FractureTesting. Compr. Struct. Integr. 2023, 8, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirotti, S.; Pelliciari, M.; Tarantino, A.M. Effect of compressibility on the mechanics of hyperelastic membranes. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 278, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.B.; Lee, H.K.; AnfHyun-ChulPark, H.C. Measurement of mechanical properties of thin films using a combination of the bulge test and nanoindentation. Trans. Korean Soc. Mech. Eng. B 2012, 36, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, O. Thin Films: Mechanical Testing. Encycl. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 9257–9261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, J. Elasticity/Hyperelasticity. In Mechanics of Solid Polymers Theory and Computational Modeling; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlowec, J.; Wineman, A.; Hulbert, G. Elastomer bushing response: Experiments and finite element modeling. Acta Mech. 2003, 163, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Griffin, M.J. Finite element modelling of human-seat interactions: Vertical in-line and fore-and-aft cross-axis apparent mass when sitting on a rigid seat without backrest and exposed to vertical vibration. Ergonomics 2015, 58, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.C.; He, L.; Du, W.; Cao, Z.K.; Huang, Z.L. Effect of sitting posture and seat on biodynamic responses of internal human body simulated by finite element modeling of body-seat system. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 438, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefert, A.; Pankoke, S. Development of a Detailed Buttock and Thigh Muscle Model casimir. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mech. Syst. 2018, 1, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Phillips, E.; Grimshaw, P.; Portus, M.; Robertson, W.S.P. Effect of Seating Cushions on Pressure Distribution in Wheelchair Racing. ISBS Proc. Arch. 2017, 35, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. A new custom-contoured cushion system based on finite element modeling prediction. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2013, 13, 1350051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsous, M.; Lim, D.; Hendrix, R.; Bankard, J.; Rymer, W.Z.; Lin, F. Finite element analysis for evaluation of pressure ulcer on the buttock: Development and validation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2007, 15, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; He, Y. Modeling of human model for static pressure distribution prediction. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 50, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, J. Study on Virtual Simulation Method of Driver Seat Comfort. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 493, 012096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonnet, L.; Wang, X.; Duprey, S. Finite element models of the thigh-buttock complex for assessing static sitting discomfort and pressure sore risk: A literature review. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2018, 21, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Smith, J.A.; Fleming, S.M. Considerations and Experiences in Developing a Finite Element Buttock Model for Seating Comfort Analysis; Dayton OH 45431-1289 Biosciences and Protection Division Human Effectiveness Directorate Biosciences and Protection Division Biomechanics Branch; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carfagni, M.; Governi, L.; Volpe, Y. Comfort assessment of motorcycle saddles: A methodology based on virtual prototypes. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2007, 1, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, T.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Jung, S.; Yang, D.; Hong, J. A design for seat cushion and back-supporter using finite element analysis for preventing decubitus ulcer. J. Biomech. Sci. Eng. 2017, 12, 16–00586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Reed, M. Development of a methodology for simulating seat back interaction using realistic body contours. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Mech. Syst. 2013, 6, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennestri, E.; Valentini, P.P.; Vita, L. Comfort analysis of car occupants: Comparison between multibody and finite element models. Int. J. Veh. Syst. Model. Test. 2005, 1, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stature (mm) | Body Mass (kg) | Thigh Length (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1720 | 72 | 430 |

| Term k | Relaxation Time | Prony Coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.733073 | 0.0181693 |

| 2 | 0.799137 | 0.0725529 |

| 3 | 6.81538 | 0.0914753 |

| 4 | 10.2102 | 0.0695494 |

| 5 | 17.0064 | 0.00251894 |

| 6 | 251.667 | 0.0251244 |

| 7 | 8890.97 | 0.00165894 |

| 8 | 16,063.3 | 0.14635 |

| 9 | 17,171.8 | 0.000349927 |

| Sensor Matrix | Sensor Spacing | Technology | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48 × 48 | 0.5 inch | capacitive | 0 ÷ 27 kPa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, X.-T.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Nguyen, D.-T. Finite Element Analysis of the Contact Pressure for Human–Seat Interaction with an Inserted Pneumatic Spring. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2687. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052687

Tran X-T, Nguyen V-H, Nguyen D-T. Finite Element Analysis of the Contact Pressure for Human–Seat Interaction with an Inserted Pneumatic Spring. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(5):2687. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052687

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Xuan-Tien, Van-Ha Nguyen, and Duc-Toan Nguyen. 2025. "Finite Element Analysis of the Contact Pressure for Human–Seat Interaction with an Inserted Pneumatic Spring" Applied Sciences 15, no. 5: 2687. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052687

APA StyleTran, X.-T., Nguyen, V.-H., & Nguyen, D.-T. (2025). Finite Element Analysis of the Contact Pressure for Human–Seat Interaction with an Inserted Pneumatic Spring. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2687. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052687