Application of Augmented Reality, Mobile Devices, and Sensors for a Combat Entity Quantitative Assessment Supporting Decisions and Situational Awareness Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Introduction to Analytical Scenario

3. Tactical Calculation Methodology and Situational Awareness Evaluation Algorithms

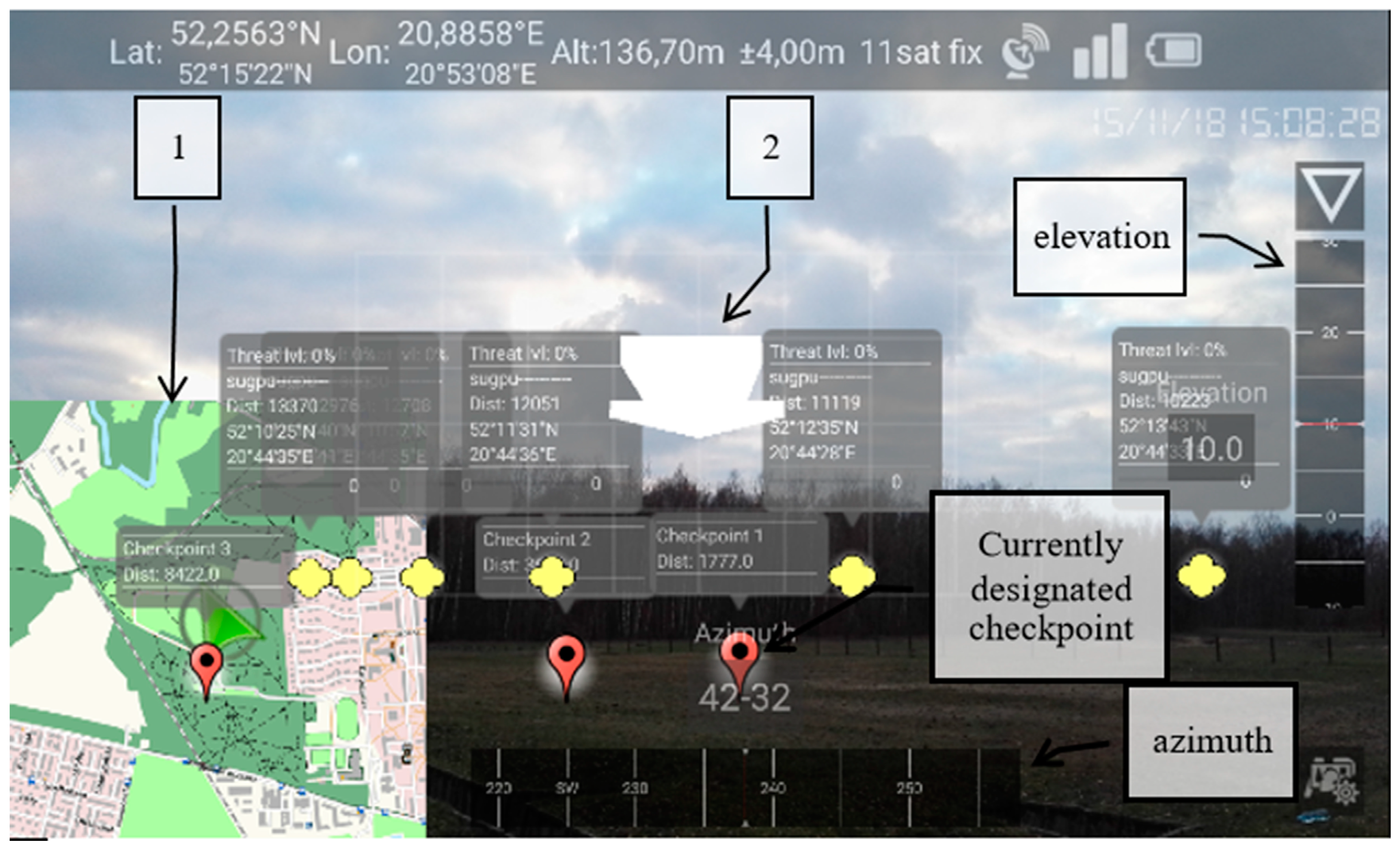

4. Threat-Level Assessment Methods

5. Task Guidance and Location Monitoring

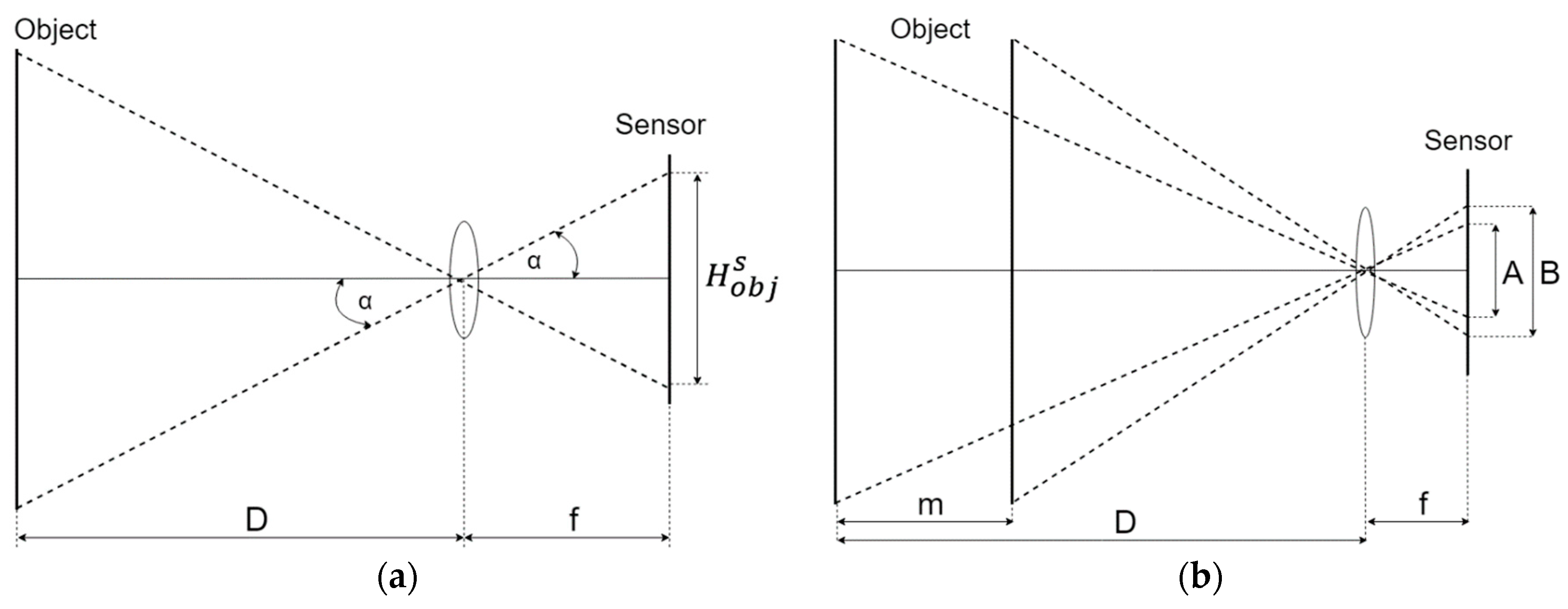

6. Methods for Reconnaissance Support

7. Measurement Data Reports

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US DoD (US Department of Defense). Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, Joint Publication 1–02; US Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Taylor, J.G. Lanchester Type Models of Warfare vol. I, Operations Research, Naval Postgraduate School Monterey. 1980. Available online: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a090842.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- NC3A. NATO Common Operational Picture (NCOP)—NC3A; NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M. Data fusion based on ontology model for common operational picture using OpenMap and Jena semantic framework. In Proceedings of the Military Communications and Information Systems Conference, Cracow, Poland, 22–24 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.L.; Llinas, J. Handbook of Multisensor Data Fusion; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Sapiejewski, K. Augmented reality mechanisms in mobile decision support systems supporting combat forces and terrain calculations-a case study. In Proceedings of the Geographic Information Systems Conference and Exhibition “GIS ODYSSEY 2018”, Perugia, Italy, 10–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Kukiełka, M.; Gutowski, T.; Pieczonka, P. Handheld combat support tools utilising IoT technologies and data fusion algorithms as reconnaissance and surveillance platforms. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Limerick, Irleand, 15–18 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Gałka, A. Semantic battlespace data mapping using tactical symbology. In Advances in Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 283, pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bonder, S. Army operations research—Historical perspectives and lessons learned. Oper. Res. 2002, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M. Situation awareness tools supporting soldiers and low level commanders in land operations. Application of GIS and augmented reality mechanisms. In Proceedings of the Geographic Information Systems Conference and Exhibition “GIS ODYSSEY 2017”, Trento, Italy, 4–8 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.; Hartman, J.; Parry, S.; Washburn, A.; Youngren, M. Aggregated Combat Models. Operations Research Department—Naval Postgraduate School Monterey. 2000. Available online: https://faculty.nps.edu/awashburn/Washburnpu/aggregated.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- UK MoD (UK Ministry of Defence), 2005, Network Enabled Capability, Joint Service Publication 777. Available online: http://barrington.cranfield.ac.uk/resources/papers/JSP777 (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- Endsley, M.R.; Garland, D.J. Situation Awareness, Analysis and Measurement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CEN. Disaster and Emergency Management—Shared Situation Awareness—Part1: Message Structure; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Kulas, W.; Kukiełka, M.; Frąszczak, D.; Bugajewski, D.; Kędzior, J.; Rainko, D.; Stąpor, I.P. Development of Operational Picture in DSS Using Distributed SOA Based Environment, Tactical Networks and Handhelds; Information Systems Architecture and Technology: Selected Aspects of Communication and Computational Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-83-7493-856-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Kukiełka, M.; Frąszczak, D.; Bugajewski, D. Military and crisis management decision support tools for situation awareness development using sensor data fusion. In International Conference on Information Systems Architecture and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, M.; Kukielka, M. Applications of RFID technology in dismounted soldier solution systems—Study of mCOP system capabilities. In MATEC Web of Conferences; Edp Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołejszo, J. Ways of Calculating Combat Potential of Unit, Formation and Command (Sposoby Obliczania Potencjału Bojowego Pododdziału, Oddziału i Związku Taktycznego); National Defense Academy: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Polish General Staff. 1299/87, (PGS, 1988), Podstawowe Kalkulacje Operacyjno-Taktyczne (Basic Operational-Tactical Calculations); Polish General Staff: Warszawa, Poland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.G. Lanchester Type Models of Warfare vol. II, Operations Research, Naval Postgraduate School Monterey. 1980. Available online: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a090843.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Codenames, Tags, and Build Numbers. Available online: https://source.android.com/setup/start/build-numbers (accessed on 8 January 2018).

| Unit (Type) Name | Potential | Estimated Time of Arrival (ETA) | Threat Level (THL) | Distance | Bearing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motorized infantry battalion | 143.17 | 25 min | 0% | 11.821 m | 236.44 |

| Mechanized infantry battalion | 130.93 | 32 min | 0% | 15.103 m | 315.25 |

| (Armored) tank battalion | 138.7 | 18 min | 0% | 8376 m | 293.13 |

| Name | Quantity | Potential | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Type: Motorized Infantry Battalion | |||

| APC KTO Rosomak | 53 | 0.92 | armor |

| UKM-2000 | 36 | 0.4 | infantry |

| PKT Machine gun | 7 | 0.3 | infantry |

| sniper rifle | 13 | 0.5 | infantry |

| 0.50 rifle | 4 | 0.55 | infantry |

| Recon Vehicle | 3 | 0.45 | armor |

| RPG-7 | 43 | 0.12 | infantry |

| 60-mm Mortar | 12 | 0.56 | artillery |

| 98-mm Mortar | 6 | 0.58 | artillery |

| PPK SPIKE | 6 | 0.75 | artillery |

| Mk-19 | 12 | 4.0 | infantry |

| Unit Type: Mechanized Infantry Battalion | |||

| Machine gun | 41 | 0.3 | infantry |

| sniper rifle | 13 | 0.5 | infantry |

| 0.50 rifle | 4 | 0.55 | infantry |

| Mk-19 | 12 | 4.0 | infantry |

| RPG-7 | 53 | 0.12 | infantry |

| Recon Vehicle | 3 | 0.45 | armor |

| BWP-1 | 53 | 0.8 | armor |

| 120-mm Mortar | 6 | 0.97 | artillery |

| 9P133 malyutka | 6 | 1.0 | artillery |

| Unit Type: (Armored) Tank Battalion | |||

| machine gun | 2 | 0.3 | infantry |

| RPG-7 | 5 | 0.12 | infantry |

| PT-91 tank | 58 | 2.35 | armor |

| BWR-1D | 3 | 0.4 | armor |

| Finding Distance to the Nearest Unit (s) | Finding Closest Allied Unit for Support (s) | Topographical Orientation (s) | Tactical Situation Orientation (s) | Finding Point of Interest (POI) (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Experience | Map | mCOP | Map | mCOP | Map | mCOP | Map | mCOP | Map | mCOP |

| low | 7.66 1.02 | 2.18 0.44 | 3.90 1.16 | 4.13 0.83 | 5.99 0.93 | 2.30 0.52 | 16.63 0.64 | 13.59 1.39 | 3.48 0.97 | 3.56 0.45 |

| medium | 10.47 0.68 | 3.24 0.31 | 6.14 0.44 | 5.55 0.32 | 8.27 0.48 | 3.25 0.11 | 18.49 0.56 | 16.58 0.78 | 5.53 0.44 | 5.01 0.40 |

| high | 12.37 1.02 | 4.31 0.36 | 7.89 0.64 | 7.11 0.68 | 10.84 1.34 | 4.10 0.42 | 21.48 1.53 | 20.33 1.39 | 7.22 0.86 | 6.79 0.66 |

| all | 10.28 2.24 | 3.29 0.98 | 6.07 1.89 | 5.66 1.43 | 8.48 2.30 | 3.28 0.91 | 19.01 2.39 | 17.03 3.26 | 5.49 1.79 | 5.20 1.49 |

| Group Experience | Finding Distance to the Nearest Unit | Finding Closest Allied Unit for Support | Topographical Orientation | Tactical Situation Orientation | Finding POI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low | −71.5% | +5.9% | −61.6% | −18.3% | +2.3% |

| medium | −69.1% | −9.6% | −60.7% | −10.3% | −9.4% |

| high | −65.2% | −9.9% | −62.2% | −5.4% | −6% |

| All | −68% | −6.8% | −61.3% | −10.4% | −5.3% |

| No | D (m) | MA (m) | MB (m) | m (m) | X (m) | Y (m) | δA (%) | δB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.05 | 22.90 | 23.90 | ~2 [1.96] | 22.96 | 23.50 | 0.65% | 3.69% |

| 2 | 22.37 | 22.33 | 18.99 | ~2 [1.88] | 22.35 | 21.24 | 0.18% | 9.88% |

| 3 | 15.15 | 15.06 | 14.65 | ~2 [2.01] | 15.04 | 14.87 | 0.59% | 3.30% |

| 4 | 14.12 | 13.95 | 12.99 | 2 | 13.97 | 14.10 | 1.20% | 8.00% |

| 5 | 6.05 | 5.98 | 5.95 | ~2 [1.95] | 5.97 | 5.96 | 1.16% | 1.65% |

| 6 | 6.09 | 5.97 | 5.95 | ~2 [2.06] | 5.98 | 5.96 | 1.97% | 2.30% |

| 7 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0% | 0% |

| 8 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0% | 0% |

| Operation Delays | Measurement Method A | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Operation Time (s) | Distance D (m) | ||

| 1 | 900 | 3.02 | 800 | 2025.97 |

| 2 | 800 | 3.16 | 900 | 1800.87 |

| 3 | 700 | 3.42 | 1000 | 1620.78 |

| 4 | 600 | 3.81 | 1001 | 1619.16 |

| 5 | 500 | 4.24 | 1002 | 1617.55 |

| 6 | 400 | 4.93 | 1003 | 1615.93 |

| 7 | 300 | 5.87 | 1200 | 1350.65 |

| 8 | 200 | 7.08 | 1500 | 1080.52 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmielewski, M.; Sapiejewski, K.; Sobolewski, M. Application of Augmented Reality, Mobile Devices, and Sensors for a Combat Entity Quantitative Assessment Supporting Decisions and Situational Awareness Development. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214577

Chmielewski M, Sapiejewski K, Sobolewski M. Application of Augmented Reality, Mobile Devices, and Sensors for a Combat Entity Quantitative Assessment Supporting Decisions and Situational Awareness Development. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214577

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmielewski, Mariusz, Krzysztof Sapiejewski, and Michał Sobolewski. 2019. "Application of Augmented Reality, Mobile Devices, and Sensors for a Combat Entity Quantitative Assessment Supporting Decisions and Situational Awareness Development" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214577

APA StyleChmielewski, M., Sapiejewski, K., & Sobolewski, M. (2019). Application of Augmented Reality, Mobile Devices, and Sensors for a Combat Entity Quantitative Assessment Supporting Decisions and Situational Awareness Development. Applied Sciences, 9(21), 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214577