Physiological Control Law for Rotary Blood Pumps with Full-State Feedback Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

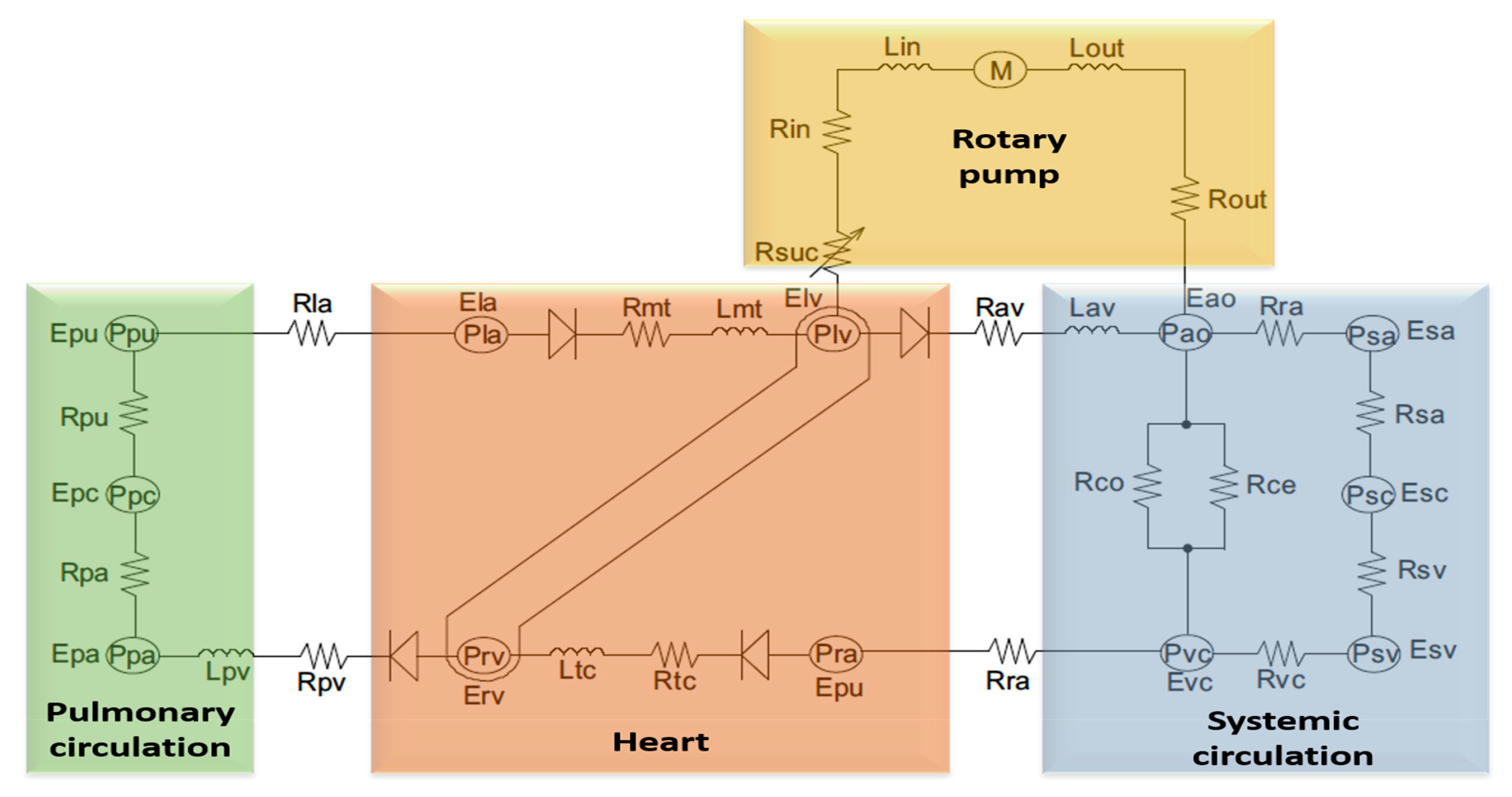

2.1. A Model of Cardiovascular System Environment with a Left Ventricular Assist Device

- Electrical equation of motor winding:where is the motor terminal voltage, is the electrical speed, is the motor winding resistance, is the motor phase current, is the motor winding inductance, and is the constant.

- Electromagnetic torque equation:where is the input electromagnetic torque, is the pump flow rate; and is the moment of inertia of the impeller.

- Pump hydraulic equation:where is the differential pressure across the pump, and , and are constant.

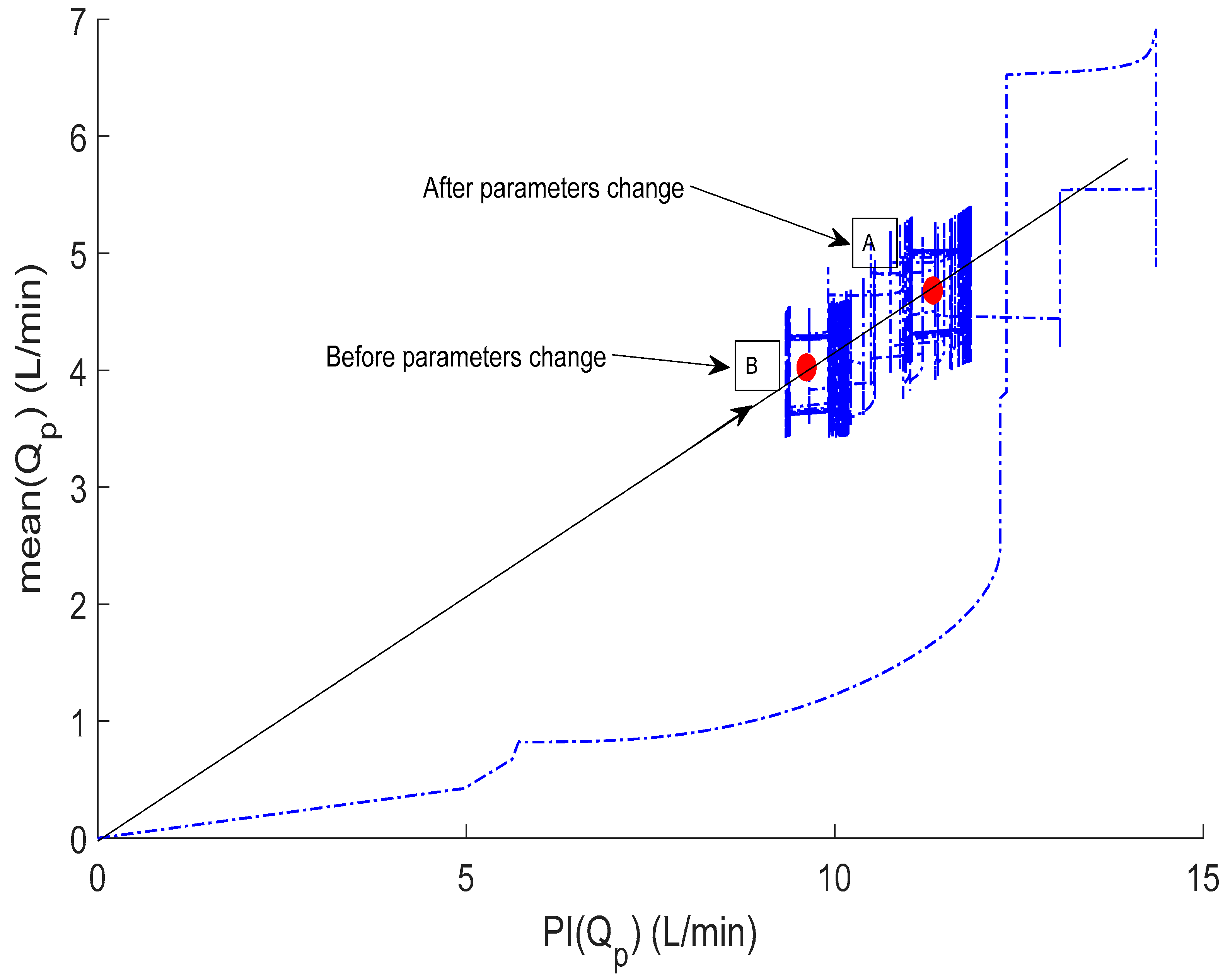

2.2. Hemodynamic Characteristics of the Model

2.3. Control Strategy with a Pulsatile of Pump Flow

2.4. Pulsatility Controller Design

2.5. Simulation Protocols

3. Results

3.1. Immediate Reactions to Short-Term Changes in Circulation

3.2. Controller Adaptive Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cowie, M.R. The heart failure epidemic: A UK perspective. Echo Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowie, M.R.; Wood, D.A.; Coats, A.J.; Thompson, S.G.; Poole-Wilson, P.A.; Suresh, V.; Sutton, G.C. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur. Heart J. 1999, 20, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.; Cowie, M.; Wood, D.; Coats, A.; Gibbs, J.; Underwood, S.; Turner, R.; Poole-Wilson, P.; Davies, S.; Sutton, G. Coronary artery disease as the cause of incident heart failure in the population. Eur. Heart J. 2001, 22, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Schmitto, J.D. The evolution of mechanical circulatory support (MCS): A new wave of developments in MCS and heart failure treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10 (Suppl. 15), S1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, O.H. Mechanical cardiac assistance: Historical perspectives. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000, 12, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granegger, M.; Schima, H.; Zimpfer, D.; Moscato, F. Assessment of Aortic Valve Opening During Rotary Blood Pump Support Using Pump Signals. Artif. Organs 2013, 38, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topilsky, Y.; Pereira, N.L.; Shah, D.K.; Boilson, B.; Schirger, J.A.; Kushwaha, S.S.; Joyce, L.D.; Park, S.J. Left ventricular assist device therapy in patients with restrictive and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlOmari, A.H.; Savkin, A.V.; Stevens, M.; Mason, D.G.; Timms, D.L.; Salamonsen, R.F.; Lovell, N.H. Developments in control systems for rotary left ventricular assist devices for heart failure patients: A review. Physiol. Meas. 2012, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, S. Physiologic outcome of varying speed rotary blood pump support algorithms: A review study. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2016, 39, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Dokos, S.; Salamonsen, R.; Rosenfeldt, F.; Ayre, P.; Lovell, N. Numerical Optimization Studies of Cardiovascular-Rotary Blood Pump Interaction. Artif. Organs 2012, 36, E110–E124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakouri, M.A.; Salamonsen, R.F.; Savkin, A.V.; AlOmari, A.H.; Lim, E.; Lovell, N.H. A Sliding Mode-Based Starling-Like Controller for Implantable Rotary Blood Pumps. Artif. Organs 2014, 38, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollkron, M.; Schima, H.; Huber, L.; Benkowski, R.; Morello, G.; Wieselthaler, G. Development of a Reliable Automatic Speed Control System for Rotary Blood Pumps. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005, 24, 1878–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boston, J.; Antaki, J.; Simaan, M. Hierarchical control of heart-assist devices. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2003, 10, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, V.; Rydén, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; Crijns, H.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Halperin, J.L.; Le Heuzey, J.Y.; Kay, G.N.; Lowe, J.E.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation–executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation). Eur. Heart J. 2007, 48, 854–906. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J.; Wallukat, G. Patients who Have Dilated Cardiomyopathy Must Have a Trial of Bridge to Recovery (Pro). Heart Fail. Clin. 2007, 3, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giridharan, G.; Skliar, M. Control Strategy for Maintaining Physiological Perfusion with Rotary Blood Pumps. Artif. Organs 2003, 27, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Allaire, P.; Tao, G.; Olsen, D. Modeling, Estimation, and Control of Human Circulatory System with a Left Ventricular Assist Device. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2007, 15, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamonsen, R.; Mason, D.; Ayre, P. Response of Rotary Blood Pumps to Changes in Preload and Afterload at a Fixed Speed Setting Are Unphysiological When Compared with the Natural Heart. Artif. Organs 2011, 35, E47–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Antaki, J.F.; Amin, D.V.; Boston, J.R.; Kerrigan, J.P.; Mandarino, W.A.; Litwak, P.; Yamazaki, K.; Macha, M.; Butler, K.C.; et al. Controller for an Axial Flow Blood Pump. Artif. Organs 1996, 20, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, K.; Oshikawa, M.; Onitsuka, T.; Nakamura, K.; Anai, H.; Yoshihara, H. Detection of Total Assist and Sucking Points Based on Pulsatility of a Continuous Flow Artificial Heart: In Vitro Evaluation. ASAIO J. 1998, 44, M708–M711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshikawa, M.; Araki, K.; Endo, G.; Anai, H.; Sato, M. Sensorless Controlling Method for a Continuous Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device. Artif. Organs 2000, 24, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakouri, M.A.; Savkin, A.V.; Alomari, A.H. Nonlinear modelling and control of left ventricular assist device. Electron. Lett. 2015, 51, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Evenson, A.; Chin, B.J.; Kunselman, A.R.; Ündar, A. Evaluation of conventional nonpulsatile and novel pulsatile extracorporeal life support systems in a simulated pediatric extracorporeal life support model. Artif. Organs 2015, 39, E1–E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucy, K.G.; Giridharan, G.A.; Choi, Y.; Sobieski, M.A.; Monreal, G.; Cheng, A.; Schumer, E.; Slaughter, M.S.; Koenig, S.C. Rotary pump speed modulation for generating pulsatile flow and phasic left ventricular volume unloading in a bovine model of chronic ischemic heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Boston, J.R.; Antaki, J.F. Hemodynamic controller for left ventricular assist device based on pulsatility ratio. Artif. Organs 2007, 31, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, B.C.; Kleinheyer, M.; Smith, P.A.; Timms, D.; Cohn, W.E.; Lim, E. Pulsatile operation of a continuous-flow right ventricular assist device (RVAD) to improve vascular pulsatility. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamonsen, R.F.; Lim, E.; Gaddum, E.; Alomari, A.H.; Gregory, S.D.; Stevens, M.; Mason, D.G.; Fraser, J.F.; Timms, D.; Karunanithi, M.K.; et al. Theoretical foundations of a Starling-like controller for rotary blood pumps. Artif. Organs 2012, 36, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, G.F.; Powell, J.D.; Emami-Naeini, A. Feedback Control of Dynamic Systems; Prentice Hall Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bakouri, M. Evaluation of an advanced model reference sliding mode control method for cardiac assist device using a numerical model. IET Syst. Biol. 2018, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakouri, M. Physiological Control Approach for Heart Pump. In Proceedings of the 2019 18th European Control Conference (ECC), Naples, Italy, 25–28 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Shekar, K.; Gregory, S.D.; Fraser, J.F. Mechanical circulatory support in the new era: An overview. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Koenig, S.C.; Wu, Z.; Slaughter, M.S.; Giridharan, G.A. Sensor-based physiologic control strategy for biventricular support with rotary blood pumps. ASAIO J. 2018, 64, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, J.P.; Stevens, M.C.; Bartnikowski, N.; Fraser, J.F.; Gregory, S.D.; Tansley, G. Evaluation of physiological control systems for rotary left ventricular assist devices: An in-vitro study. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollkron, M.; Schima, H.; Huber, L.; Benkowski, R.; Morello, G.; Wieselthaler, G. Development of a Suction Detection System for Axial Blood Pumps. Artif. Organs 2004, 28, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakouri, M.A.; Savkin, A.V.; Alomari, A.H. A method for physiological control of a cardiac assist device. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 31 May–3 June 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, G.; Araki, K.; Kojima, K.; Nakamura, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Onitsuka, T. The Index of Motor Current Amplitude Has Feasibility in Control for Continuous Flow Pumps and Evaluation of Left Ventricular Function. Artif. Organs 2001, 25, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Unit | Healthy | Heart Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricle contractility () | mm Hg/mL | 3.5443 | 0.7100 |

| Right ventricle contractility () | mm Hg/mL | 1.7235 | 0.5322 |

| Systemic peripheral resistance () | mm Hg*s/mL | 0.7411 | 1.1100 |

| Total blood volume () | mL | 5300 | 5800 |

| Variable | Symbol | Unit | Healthy | Heart Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-diastolic left ventricle volume | mL | 133.35 | 183.21 | |

| End-systolic left ventricle volume | mL | 63.05 | 150.00 | |

| End-diastolic left ventricle pressure | mmHg | 7.11 | 22.23 | |

| End-systolic left ventricle pressure | mmHg | 130.00 | 89.56 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakouri, M. Physiological Control Law for Rotary Blood Pumps with Full-State Feedback Method. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214593

Bakouri M. Physiological Control Law for Rotary Blood Pumps with Full-State Feedback Method. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214593

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakouri, Mohsen. 2019. "Physiological Control Law for Rotary Blood Pumps with Full-State Feedback Method" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4593. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214593