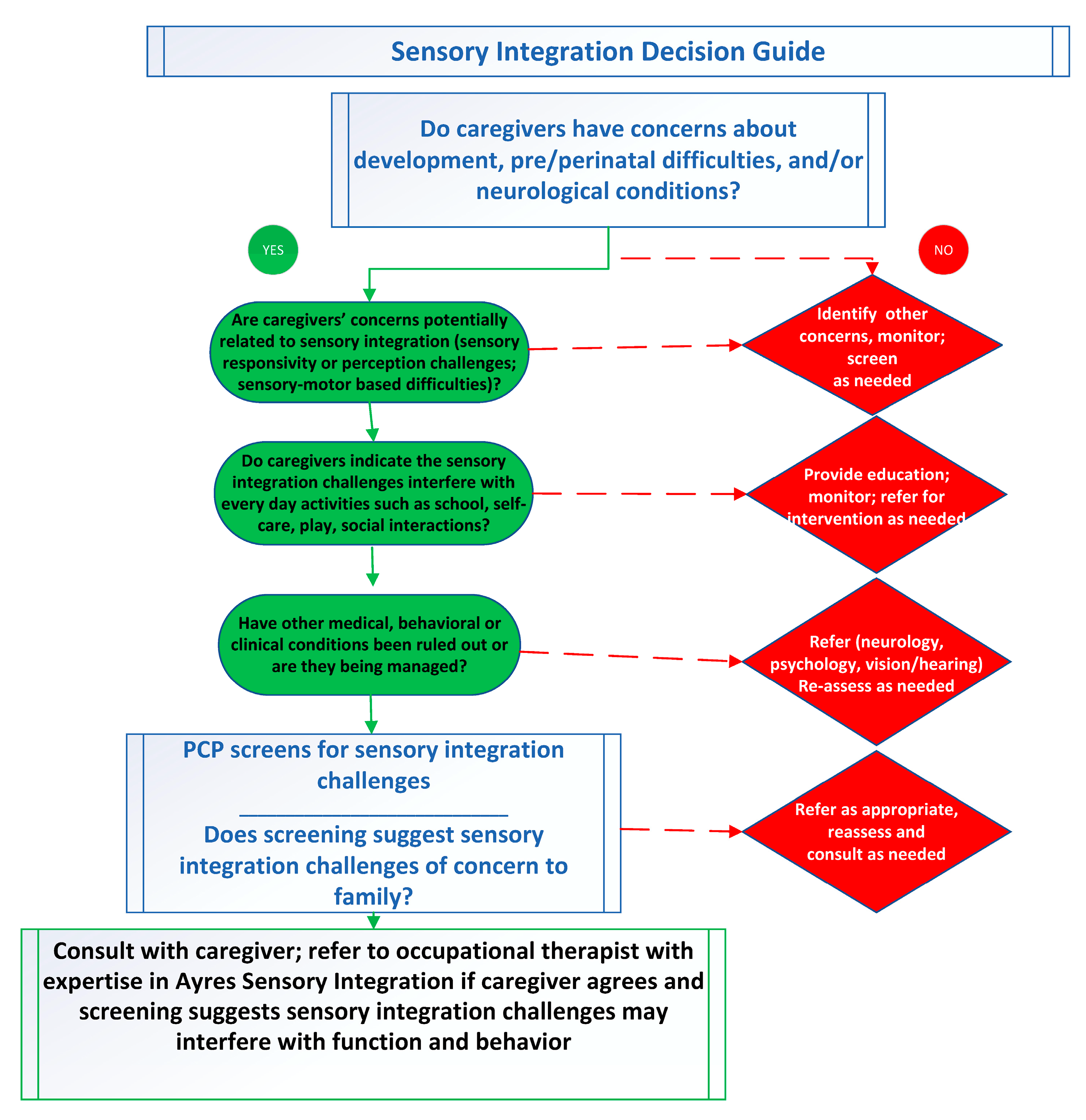

Supporting Clinical Identification of Children with Sensory Integration Challenges: A Decision Guide for Primary Care Providers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- All population terms + screening;

- (2)

- All population terms +all referral terms;

- (3)

- (All population terms + screening) + all primary care terms;

- (4)

- (All population terms +all referral terms) + all primary care terms;

- (5)

- (All population terms + all referral terms) + all occupational therapy terms;

- (6)

- ((All population terms + all referral terms) + (all occupational therapy terms) + (all primary care terms)).

3. Results

3.1. Understanding Sensory Integration

3.2. Screening and Referral

3.3. The Need for a Sensory Integration Decision Guide

- Is the child picky about certain tastes or textures when eating?

- Does the child have difficulty getting dressed or finding comfortable clothing?

- Has the child been sensitive to sounds?

- Does the child withdraw when there is noisy group play?

- Do sensory experiences like these interfere with social or academic functioning?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lane, S.J.; Mailloux, Z.; Schoen, S.; Bundy, A.; May-Benson, T.A.; Parham, L.D.; Smith Roley, S.; Schaaf, R.C. Neural Foundations of Ayres Sensory Integration®. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, A.J. Sensory Integration and Learning Disorders; Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, L.D.; Cohn, E.S.; Spitzer, S.; Koomar, J.A.; Miller, L.J.; Burke, J.P.; Brett-Green, B.; Mailloux, Z.; May-Benson, T.A.; Smith Roley, S.; et al. Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 61, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parham, L.D.; Roley, S.S.; May-Benson, T.A.; Koomar, J.; Brett-Green, B.; Burke, J.P.; Cohn, E.S.; Mailloux, Z.; Miller, L.J.; Schaaf, R.C. Development of a fidelity measure for research on the effectiveness of the Ayres Sensory Integration intervention. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Mailloux, Z. A Clinician’s Guide for Implementing Ayres Sensory Integration: Promoting Participation for Children with Autism; AOTA Press: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Toth-Cohen, S.; Johnson, S.L.; Outten, G.; Benevides, T.W. The everyday routines of families of children with autism: Examining the impact of sensory processing difficulties on the family. Autism 2011, 15, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, E.; Brown, T. An investigation of the association between school-aged children’s sensory processing and their self-reported leisure activity participation and preferences. J. Occup. Ther. Schls. Early 2022, 16, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, A.G.; McKendry, S.; Soehner, A.; Bodison, S.; Akcakaya, M.; DeAlmeida, D.; Bendixen, R. Characterizing sleep differences in children with and without sensory sensitivities. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 875766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.J.; Leão, M.A.; Spielmann, V. Sleep, sensory integration/processing, and autism: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 877527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliotti, F.; Giovannone, F.; Belli, A.; Sogos, C. Atypical sensory processing in neurodevelopmental disorders: Clinical phenotypes in preschool-aged children. Children 2024, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, S.Y.; Ee, S.I.; Marret, M.J. Sensory processing and its relationship to participation among childhood occupations in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Exploring the profile of differences. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 69, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.C.; Tseng, M.H.; Fu, C.P.; Chuang, I.C.; Lu, L.; Shieh, J.Y. Exploring sensory processing dysfunction, parenting stress, and problem behaviors in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 73, 7301205130p1–7301205130p10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Z.A.M.; Boulton, K.A.; Thapa, R.; DeMayo, M.M.; Ambarchi, Z.; Thomas, E.; Pokorski, I.; Hickie, I.B.; Guastella, A.J. Atypical sensory processing features in children with autism, and their relationships with maladaptive behaviors and caregiver strain. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Zisserman, A. Sensory family accommodation for autistic and sensory overresponsive children: The mediating role of parenting distress tolerance. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2025, 79, 7903205110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourley, L.; Wind, C.; Henninger, E.M.; Chinitz, S. Sensory processing difficulties, behavioral problems, and parental stress in a clinical population of young children. JCFS 2013, 22, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.V.; Dickie, V.A.; Baranek, G.T. Sensory experiences of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: In their own words. Autism 2015, 19, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L.M.; Ausderau, K.; Freuler, A.; Sideris, J.; Baranek, G.T. Caregiver strategies to sensory features for children with autism and developmental disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 905154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, A.; Lane, S.J. Sensory integration: A Jean Ayres theory revisited. In Sensory Integration Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Bundy, A., Lane, S.J., Eds.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cermak, S.A.; May-Benson, T. Praxis and dyspraxia. In Sensory Integration Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Bundy, A., Lane, S.J., Eds.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Mackintosh, V.H.; Myers, B.J. Parental reports on the efficacy of treatments and therapies for their children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disorder 2009, 3, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, V.A.; Pituch, K.A.; Itchon, J.; Choi, A.; O’Reilly, M.; Sigafoos, J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.E.; Baron-Cohen, S. Sensory perception in autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino-Alarcón, J.; Robles-Bello, M.A.; Valencia-Naranjo, N.; Sarhani-Robles, A.A. Systematic review of treatment for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The sensory processing and sensory integration approach. Children 2024, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Mailloux, Z.; Ridgway, E.; Berruti, A.S.; Dumont, R.L.; Jones, E.A.; Leiby, B.E.; Sancimino, C.; Yi, M.; Molholm, S. Sensory phenotypes in autism: Making a case for the inclusion of sensory integration functions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 4759–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, L.; Duchier, A.; Gauld, C.; Hénault, L.; Giroudon, C.; Fourneret, P.; Cortese, S.; Nourredine, M. Sensory processing in individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder compared with control populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 64, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, R.R.; Miller, L.J.; Milberger, S.; McIntosh, D.N. Prevalence of parents’ perceptions of sensory processing disorders among kindergarten children. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 58, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouze, K.R.; Hopkins, J.; LeBailly, S.A.; Lavigne, J.V. Re-examining the epidemiology of sensory regulation dysfunction and comorbid psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussila, K.; Junttila, M.; Kielinen, M.; Ebeling, H.; Joskitt, L.; Moilanen, I.; Mattila, M.L. Sensory abnormality and quantitative autism traits in children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder in an epidemiological population. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.S.; Ben-Sasson, A.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. Sensory over-responsivity, psychopathology, and family impairment in school-aged children. JAACAP 2011, 50, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana, A.; Flores-Ripoll, J.M.; Benito-Castellanos, P.J.; Villar-Rodriguez, C.; Vela-Romero, M. Prevalence and severity-based classification of sensory processing issues. An exploratory study with neuropsychological implications. App. Neuropsychol. Child 2022, 11, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Wiggins, L.D.; Hughes, M.M.; Davis, J.; Hall-Lande, J.A.; Lee, L.C.; McMahon, W.M.; Bakian, A.V. Sensory features in autism: Findings from a large population-based surveillance system. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemant, P.; Ferzandi, Z. Ayres sensory integration for children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A mixed method study. IJAR 2020, 8, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klintwall, L.; Holm, A.; Eriksson, M.; Carlsson, L.H.; Olsson, M.B.; Hedvall, A.; Gillberg, C.; Fernell, E. Sensory abnormalities in autism. A brief report. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leekam, S.R.; Nieto, C.; Libby, S.J.; Wing, L.; Gould, J. Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, S.; Douglas, S.; Armstrong, C. Characteristics of idiopathic sensory processing disorder in young children. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J.; Schoen, S.A.; Mulligan, S.; Sullivan, J. Identification of sensory processing and integration symptom clusters: A preliminary study. Occupational Ther. Int. 2017, 2017, 2876080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomchek, S.D.; Dunn, W. Sensory processing in children with and without autism: A comparative study using the Short Sensory Profile. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 61, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, B.; Madhumita, D.; Sehgal, R. Exploring prevalence of sensory patterns among children with developmental disabilities: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2025, 12, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiris, G.; Oliver, D.P.; Washington, K.T. Defining and analyzing the problem. In Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care Building an Evidence Base; Demiris, G., Oliver, D.P., Washington, K.T., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andelin, L.; Reynolds, S.; Schoen, S. Effectiveness of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach: A multiple-baseline design study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 75, 7506205030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuona, E.; Van Jaarsveld, A.; Raubenheimer, J.; Van Heerden, R. Sensory integration intervention and the development of the premature infant: A controlled trial. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.J.; Reynolds, S. Sensory over-responsivity as an added dimension in ADHD. Fronti. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Benson, T.A.; Easterbrooks-Dick, O.; Teasdale, A. Exploring the prognosis: A longitudinal follow-up study of children with sensory processing challenges 8-32 years later. Children 2023, 10, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuiddy, V.A.; Ingram, M.; Vines, M.; Teeters, S.; Ramstetter, A.; Strain-Roggs, S. Long-term impact of an occupational therapy intervention for children with challenges in sensory processing and integration. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 78, 7804185060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J.; Anzalone, M.E.; Lane, S.J.; Cermak, S.A.; Osten, E.T. Concept evolution in sensory integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 61, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, M.J.; Lane, S.J.; Haracz, K.; Tona, J.; Palazzi, K.; Lambkin, D. Relationships between sensory reactivity and occupational performance in children with Paediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS). Aust. Ooccup. Ther. J. 2025, 72, e12999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omairi, C.; Mailloux, Z.; Antoniuk, S.A.; Schaaf, R. Occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration®: A randomized controlled trial in Brazil. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7604205160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, B.A.; Koenig, K.; Kinnealey, M.; Sheppard, M.; Henderson, L. Effectiveness of sensory integration interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Benevedies, R.; Mailloux, Z.; Faller, P.; Hunt, J.; van Hooydonk, E.; Freeman, R.; Leiby, B.; Sendecki, J.; Kelly, D. An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 447, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, R.C.; Ridgway, E.M.; Jones, E.A.; Dumont, R.L.; Foxe, J.; Conly, T.; Sancimino, C.; Misung, Y.; Mailloux, Z.; Hunt, J.M.; et al. A comparative trial of occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration and applied behavior analysis interventions for autistic children. Autism Res. 2025, 10, 2120–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, C.C.; Schoen, S.A.; Schaaf, R.C.; Auld-Wright, K.; McKeon, M.C. Guidelines for occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration® in school-based practice: A validation study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2025, 79, 7904205190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnaro, B.H.; Pauletti, M.F.; Lima, C.R.G.; Verdério, B.N.; Fonseca-Angulo, R.I.; Romão-Silva, B.; de Campos, A.C.; Rosenbaum, P.; Rocha, N.A.C.F. Relationship between sensory processing patterns and gross motor function of children and adolescents with Down syndrome and typical development: A cross-sectional study. JIDR 2024, 68, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, A.; van Rooyen, F.C.; van Biljon, A.-M.; van Rensburg, I.J.; James, K.; Böning, L.; Haefele, L. Sensory processing, praxis and related social participation of 5–12 year old children with Down Syndrome attending educational facilities in Bloemfontein, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 46, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldsted, B.; Xue, L. Sensory Processing in Young Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Phys Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2019, 39, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Martin, C.D.; Lei, A.L.; Hausknecht, K.A.; Turk, M.; Micov, V.; Kwarteng, F.; Ishiwari, K.; Ourbraim, S.; Want, A.-L.; et al. Prenatal ethanol exposure impairs sensory processing and habituation of visual stimuli, effects normalized by postnatal environmental enrichment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 46, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröring, T.; Königs, M.; Oostrom, K.J.; Lafeber, H.N.; Brugman, A.; Oosterlaan, J. Sensory processing difficulties in school-age children born very preterm: An exploratory study. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 117, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.W.; Moore, E.M.; Roberts, E.J.; Hachtel, K.W.; Brown, M.S. Sensory processing disorder in children ages birth–3 years born prematurely: A systematic review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6901220030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niutanen, U.; Harra, T.; Lano, A.; Metsäranta, M. Systematic review of sensory processing in preterm children reveals abnormal sensory modulation, somatosensory processing and sensory-based motor processing. Acta Pediatr. 2020, 109, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, O.; Kaple, M. Sensory processing differences in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A narrative review of underlying mechanisms and sensory-based interventions. Cureus 2023, 15, e48020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellapiazza, F.; Vernhet, C.; Blanc, N.; Miot, S.; Schmidt, R.; Baghdadli, A. Links between sensory processing, adaptive behaviours, and attention in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donica, D.; Beck, L.; Mumford, K. Exploring the relationship between handwriting legibility and praxis in third and fourth grade students. OJOT 2025, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeman, H.R.G.; Brown, T. An exploratory study of the relationship between typically-developing school-age children’s sensory processing and their activity participation. BJOT 2021, 85, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoen, S.A.; Lane, S.J.; Mailloux, Z.; May-Benson, T.; Parham, L.D.; Smith Roley, S.; Schaaf, R.C. A systematic review of Ayres Sensory Integration intervention for children with autism. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrenner, J.R.; Hume, K.; Odom, S.L.; Morin, K.L.; Nowell, S.W.; Tomaszewski, B.; Szendrey, S.; McIntyre, N.S.; Yucesoy-Ozkan, S.; Savage, M.N. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 4013–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, S.; Uys, K.; Van Niekerk, K.; Botha, T. The impact of occupational therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration® on a child with cochlear implants: A case study (Version 1). S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2025, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, N.; Sugi, S.; Rajendran, K. A study to identify prevalence and effectiveness of sensory integration on toilet skill problems among sensory processing disorder. IJOT 2018, 50, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.C.; da Silva Pereira, A.P.; da Silva Almeida, L.; Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I. Assessment of sensory integration in early childhood: A systematic review to identify tools compatible with family-centred approach and daily routines. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early 2023, 17, 419–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C.C.; da Silva Pereira, A.P.; da Silva Almeida, L.; Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I. Construct validity of the sensory integration infant routines questionnaire (SIIRQ). Early Years 2024, 45, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. Sensory Profile 2 User Manual; Pearson Assessments: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, L.D.; Ecker, C.L.; Kuhaneck, H.; Henry, D.A.; Glennon, T.J. Sensory Processing Measure, Second Edition (SPM-2); Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Boggett-Carsjens, J. Consider sensory processing disorders in the explosive child: Case report and review. Can. Child Adoles. Psychiatry Rev. 2005, 14, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Critz, C.; Blake, K.; Nogueira, E. Sensory processing challenges in children. JNP 2015, 11, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; du Plessis, E. Sensory processing disorder: Perceptions on the clinical role of advanced psychiatric nurses. Health SA 2019, 24, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbam, K.M. The relevance of sensory processing disorder to social work practice: An interdisciplinary approach. CASWJ 2014, 31, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.K. Sensory processing disorder: Implications for primary care nurse practitioners. JNP 2020, 16, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.W. Sensory processing disorder: Any of a nurse practitioner’s business? JAANP 2009, 21, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerink, J.S.; Oudega, R.; Hopstaken, R.; Koffijberg, H.; Kusters, R. Clinical decision rules in primary care: Necessary investments for sustainable healthcare. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, S.H.; Hall, I.J.; Massetti, G.M.; Thomas, C.C.; Li, J.; Richardson, L.C. Primary care providers’ intended use of decision aids for prostate-specific antigen testing for prostate cancer screening. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 34, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnal, S.; Panda, S.; Namrata; Chettri, A. Sensory processing, emotional and behavioral challenges in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 71, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikami, M.; Hirota, T.; Takahashi, M.; Adachi, M.; Saito, M.; Koeda1, S.; Yoshida, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kato, S.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Atypical sensory processing profiles and their associations with motor problems in preschoolers with developmental coordination disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, N.; Schiowitz, B.; Rait, G.; Vickerstaff, V.; Sampson, E.J. Decision aids to support decision-making in dementia care: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Venrooij, L.T.; Rusu, V.; Vermeiren, R.R.J.M.; Koposov, R.A.; Skokauskas, N.; Crone, M.R. Clinical decision support methods for children and youths with mental health disorders in primary care. Fam. Prac. 2022, 39, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, A.J. Sensory Integration and the Child; Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cemali, M.; Pekçetin, S.; Akı, E. The effectiveness of sensory integration interventions on motor and sensory functions in infants with cortical vision impairment and cerebral palsy: A single blind randomized controlled trial. Children 2022, 9, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.L.C.; Poon, M.Y.C.; Bux, V.; Wong, S.K.F.; Chu, A.W.Y.; Louie, F.T.M.; Wang, A.Q.L.; Yang, H.L.C.; Yu, E.L.M.; Fong, S.S. Occupational therapy using an Ayres Sensory integration® approach for school-age children–a randomized controlled trial. World Fed. Occup. Ther. Bull. 2023, 79, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakal, J.Y.; Burvenich, R.; D’hulster, E.; De Rop, L.; Van den Bruel, A.; Anthierens, S.; Coenen, S.; De Sutter, A.; Heytens, S.; Joly, L.; et al. A clinical decision tool including a decision tree, point-of-care testing of CRP, and safety-netting advice to guide antibiotic prescribing in acutely ill children in primary care in Belgium (ARON): A pragmatic, cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2025, 406, 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | (“sensory processing” or “sensory integration” or “sensory modulation” or “sensory-based motor”) AND (dysfunction or disorder or challenge or difficult *) | |

| Concept | (screening or “early detection” or “early diagnosis” or “early identification”) | (referral or “referral process” or “referral pathway” or “decision guide”) |

| Context | (“primary care provider” or “primary health care provider” or “primary healthcare provider”) | (“occupational therapy” or “occupational therapist” or “occupational therapists” or ot) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lane, S.J.; Schoen, S.A.; Schaaf, R.; Bundy, A.; Mailloux, Z.; Roley, S.S.; May-Benson, T.A.; Parham, L.D. Supporting Clinical Identification of Children with Sensory Integration Challenges: A Decision Guide for Primary Care Providers. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15111184

Lane SJ, Schoen SA, Schaaf R, Bundy A, Mailloux Z, Roley SS, May-Benson TA, Parham LD. Supporting Clinical Identification of Children with Sensory Integration Challenges: A Decision Guide for Primary Care Providers. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15111184

Chicago/Turabian StyleLane, Shelly J., Sarah A. Schoen, Roseann Schaaf, Anita Bundy, Zoe Mailloux, Susanne Smith Roley, Teresa A. May-Benson, and L. Diane Parham. 2025. "Supporting Clinical Identification of Children with Sensory Integration Challenges: A Decision Guide for Primary Care Providers" Brain Sciences 15, no. 11: 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15111184

APA StyleLane, S. J., Schoen, S. A., Schaaf, R., Bundy, A., Mailloux, Z., Roley, S. S., May-Benson, T. A., & Parham, L. D. (2025). Supporting Clinical Identification of Children with Sensory Integration Challenges: A Decision Guide for Primary Care Providers. Brain Sciences, 15(11), 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15111184