Information-Seeking Behavior for COVID-19 Boosters in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

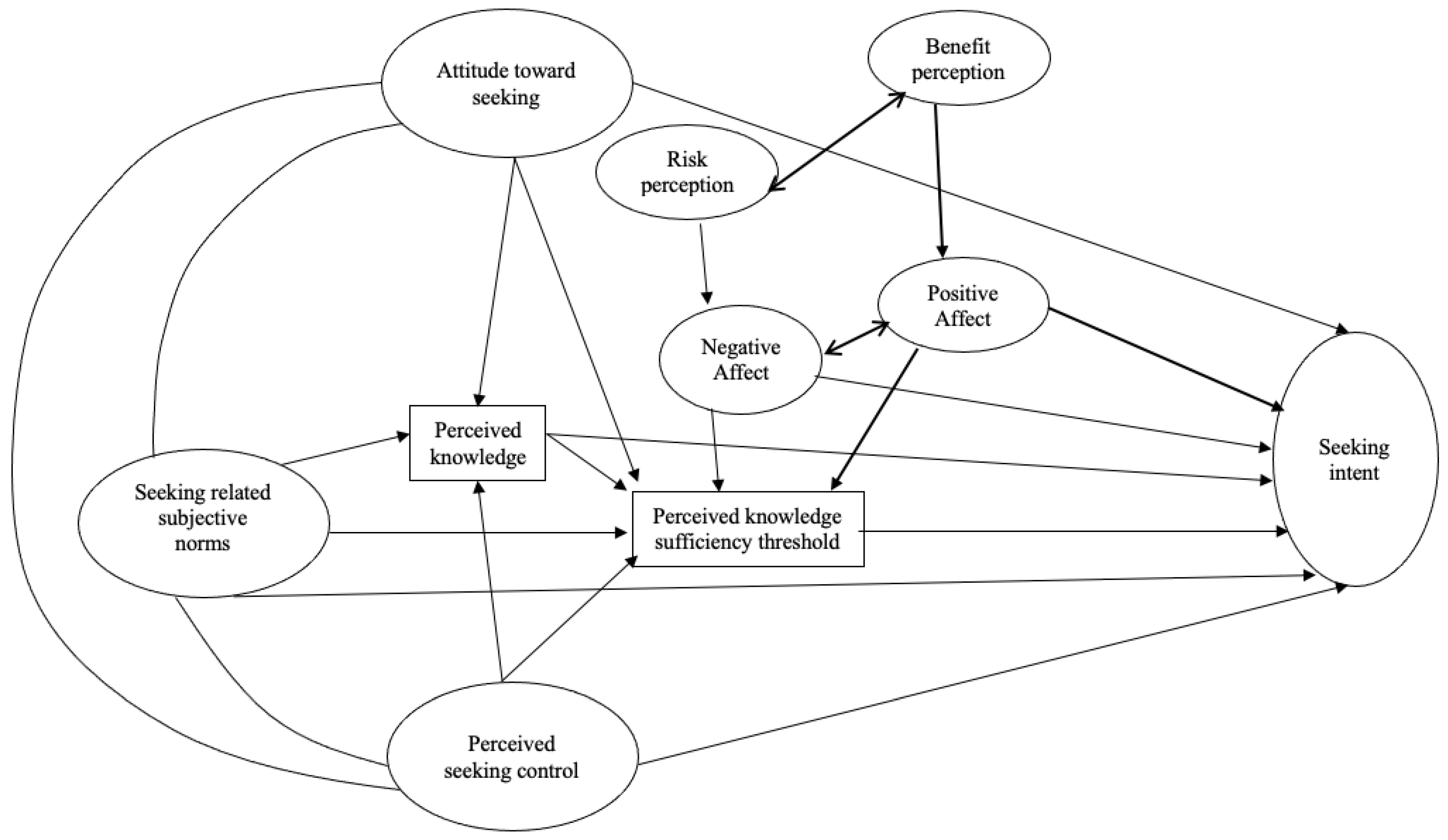

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Vaccination History

3.3. Model Fit and Relationships

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study Questionnaire

| Using the following adjective scales, please indicate to what extent you feel that seeking information about the risks and benefits posed by receiving COVID booster shots is… | |

| Attitude toward Seeking (1–5 scale) | 1. Bad…………………………. Good 2. Harmful……………………. Beneficial |

| 3. Unhelpful ……………………Helpful | |

| 4. Foolish …………………………………. Wise | |

| 5. Unproductive ………………Productive | |

| Please read the following statements and indicate your level of agreement or disagreement. Circle one answer for each item. Scale 1–5, strongly disagree to strongly agree | |

| Seeking-related Subjective Norms (1–5 scale) |

|

| |

| Please read the following statements and indicate your level of agreement or disagreement. Scale 1–5, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. | |

| Perceived Seeking Control (1–5 scale) |

|

| |

| Risk Perception (1–5 scale) | Please rate the overall level of risk posed to you by receiving COVID-19 booster shots. Use a scale of 1–5. 1 = not at all likely/serious, 5 = extremely likely/serious |

| |

| |

| |

| Please read the following statements and indicate your level of agreement or disagreement. Scale 1–5, from strongly disagree/not at all beneficial to strongly agree/extremely beneficial. | |

| Benefit Perception (1–5 scale) |

|

| The following statements describe my feelings about receiving booster shots. When I think about COVID booster shots, I get… (scale 1–7, from not at all to extremely) | |

| Affect Responses (1–7 scale) |

|

| Please read the following statements and indicate your level of agreement or disagreement. Scale 1–5, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. | |

| Information Seeking Intent (1–5 scale) |

|

| Perceived Knowledge | Rate your knowledge of the potential risks and benefits posed by receiving COVID booster shots on a scale of 0–100, where zero means knowing nothing about the topic and 100 means knowing everything you could possibly know about the potential risks and benefits. |

| Perceived Knowledge Insufficiency | Think of that same 0–100 scale again. This time, estimate how much knowledge you need to deal adequately with the potential risks/benefits posed by receiving COVID booster shots. |

References

- The Atlantic. China’s COVID Wave Is Coming. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2022/12/china-zero-covid-wave-immunity-vaccines/672375/ (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- The New York Times. China’s Looming ‘Tsunami’ of Covid Cases Will Test Its Hospitals. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/10/world/asia/china-covid-hospitals.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqjzqk/202212/6ff905b731de421f96a6228546fb848e.shtml (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- The New York Times. It Doesn’t Hurt at All’: In China’s New Covid Strategy, Vaccines Matter. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/business/china-covid-zero-vaccines.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Nature Breifing. China’s First mRNA Vaccine Is Close—Will That Solve Its COVID Woes? Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01690-3 (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Dervin, B. Information as a User Construct: The Relevance of Perceived Information Needs to Synthesis and Interpretation. In Knowledge Structure and Use: Implications for Synthesis and Interpretation; Ward, S.A., Reed, L.J., Eds.; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983; pp. 155–183. [Google Scholar]

- Marchionini, G. Information Seeking in Electronic Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021726118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoneim, S.A.; Sallam, M.; Hafez, D.M.; Elrewany, E.; Mousli, H.M.; Hammad, E.M.; Elkhadry, S.W.; Adam, M.F.; Ghobashy, A.A.; Naguib, M. COVID-19 vaccine booster dose acceptance: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Jing, R.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Guo, J.; Fang, H. Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: A cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlor, L. PRISM: A planned risk information seeking model. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovick, S.R.; Kahlor, L.; Liang, M.-C. Personal cancer knowledge and information seeking through PRISM: The planned risk information seeking model. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, J.F.; Myrick, J.K. Does context matter? Examining PRISM as a guiding framework for context-specific health risk information seeking among young adults. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlor, L.A.; Wang, W.; Olson, H.C.; Li, X.; Markman, A.B. Public perceptions and information seeking intentions related to seismicity in five Texas communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 37, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhai, G.; Zhou, S.; Fan, C.; Wu, Y.; Ren, C. Insight into the earthquake risk information seeking behavior of the victims: Evidence from Songyuan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahlor, L.A.; Yang, Z.J.; Liang, M.-C. Risky politics: Applying the planned risk information seeking model to the 2016 US presidential election. Mass. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.-H.; Fan, X. Response rates and mode preferences in web-mail mixed-mode surveys: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Internet. Sci. 2007, I2, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Bianca, M.D.; Harris, M.P. Men’s attitudes toward mask-wearing during COVID-19: Understanding the complexities of mask-ulinity. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, N.N.K.; Rahmayanti, P.L.D.; Telagawathi, N.L.W.S.; Witarsana, I.G.A.G.; Liestiandre, H.K. COVID-19 perceptions, subjective norms, and perceived benefits to attitude and behavior of continuous using of medical mask. LingCuRe 2021, 5, 1259–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, A.B.; Elliott, M.H.; Gatewood, S.B.; Goode, J.-V.R.; Moczygemba, L.R. Perceptions and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm 2022, 18, 2593–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Kim, S.; Young, S.; Steptoe, A. Positive affect and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 35, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Health information—Seeking behavior. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakami, A.S.; Slovic, P. A psychological study of the inverse relationship between perceived risk and perceived benefit. Risk Anal. 1994, 14, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covello, V.T. The perception of technological risks: A literature review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1983, 23, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Messina, F. Attitudes towards organic foods and risk/benefit perception associated with pesticides. Food Qual. Prefer 2003, 14, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G.; Roth, C. Salient value similarity, social trust, and risk/benefit perception. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Rational Actors or Rational Fools: Implications of the Affect Heuristic for Behavioral Economics. J. Socio-Econ. 2002, 31, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Detenber, B.H.; Rosenthal, S.; Lee, E.W. Seeking information about climate change: Effects of media use in an extended PRISM. Sci. Commun. 2014, 36, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC. The 47th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; Chinese Internet Network Information Centre: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.A.; Hamvas, L.; Rice, J.; Newman, D.L.; DeJong, W. Perceived social norms, expectations, and attitudes toward corporal punishment among an urban community sample of parents. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, J. The analysis of tendency of transition from collectivism to individualism in China. Cross-Cult. Commun. 2009, 5, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.H.; Davis, D.L.; Allen, J.W. Fostering corporate entrepreneurship: Cross-cultural comparisons of the importance of individualism versus collectivism. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1994, 25, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.R.; Gonçalves, A.M.; Maddux, J.E.; Carneiro, L. The intention-behaviour gap: An empirical examination of an integrative perspective to explain exercise behaviour. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 16, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Conner, M. The theory of planned behavior and exercise: Evidence for the mediating and moderating roles of planning on intention-behavior relationships. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; de Bruijn, G.J. How big is the physical activity intention–behaviour gap? A meta-analysis using the action control framework. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. An integrated behavior change model for physical activity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 42, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—Behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Org. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.W.; Selltiz, C. A multiple-indicator approach to attitude measurement. Psychol. Bull. 1964, 62, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, R.H. Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. Attitude Strength Anteced. Conseq. 1995, 4, 247–282. [Google Scholar]

| M (SD) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 31.53 (6.59) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 293 (47.6) | |

| Female | 323 (52.4) | |

| Education | ||

| General education | 2 (0.3) | |

| High school | 18 (2.9) | |

| Some college | 66 (10.7) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 486 (78.9) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 44 (7.1) | |

| Location | ||

| Northeast China | 16 (2.6) | |

| North China | 125 (20.3) | |

| Central China | 77 (12.5) | |

| East China | 201 (32.6) | |

| South China | 125 (20.3) | |

| Northwest China | 19 (3.1) | |

| Southwest China | 53 (8.6) | |

| Overseas | 0 (0) | |

| Area | ||

| Rural | 18 (2.9) | |

| Municipal | 158 (25.6) | |

| Metropolitan | 413 (67) | |

| Suburb | 27 (4.4) | |

| Income | ||

| ≤5000 | 98 (15.9) | |

| 5000–10,000 | 260 (42.2) | |

| 10,000–15,000 | 185 (30) | |

| ≥15,000 | 73 (11.9) | |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed/student/full-time caregiver | 54 (8.8) | |

| Part time | 12 (1.9) | |

| Full time | 546 (88.6) | |

| On leave | 1 (0.2) | |

| Retired | 3 (0.5) |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | ||

| None | 8 | 1.3 |

| Partial | 17 | 2.8 |

| Fully | 130 | 21.1 |

| Booster | 461 | 74.8 |

| Booster | ||

| 1 | 213 | 34.6 |

| 2 | 26 | 4.2 |

| 3 | 210 | 34.1 |

| 4 | 12 | 1.9 |

| Reason | ||

| Not convenient | 29 | 12.50% |

| Not safe | 20 | 8.60% |

| Lack instructions | 56 | 24.10% |

| Don’t care | 33 | 14.20% |

| Not efficient | 26 | 11.20% |

| Location unclear | 52 | 22.40% |

| Medical restriction | 11 | 4.70% |

| Other | 5 | 2.20% |

| Brand | ||

| BIBO | 302 | 30.50% |

| SinoVac | 457 | 46.10% |

| CanSino | 55 | 5.50% |

| Pfizer | 78 | 7.90% |

| Moderna | 16 | 1.60% |

| Janssen | 48 | 4.80% |

| AstraZeneca | 26 | 2.60% |

| Others | 9 | 0.90% |

| Model | X2 | df | CFI | TLI | Rmsea [90% C.I.] | Srmr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit–Positive affect | ||||||

| Measurement model | 933.98 | 532 | 0.946 | 0.941 | 0.037 [0.034, 0.040] | 0.036 |

| Structural model | 1286.534 | 677 | 0.957 | 0.953 | 0.038 [0.035, 0.041] | 0.053 |

| Relationships | β | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward seeking is positively related to information-seeking intent | −0.04 | 0.55 |

| Seeking-related subjective norms are positively related to information-seeking intent | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| Perceived seeking control is positively related to information-seeking intent | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Risk perception is positively related to affective (negative) risk response | 0.61 | 0.00 |

| Benefit perception is positively related to affective positive affective response | 0.86 | 0.00 |

| Affective (negative) risk response is positively related to perceived knowledge sufficiency threshold | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Positive affective response is positively related to perceived knowledge sufficiency threshold | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Affective (negative) risk response is positively related to information-seeking intent | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Positive affective response is positively related to information-seeking intent | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Attitude toward seeking is positively related to perceived knowledge | 0.05 | 0.44 |

| Seeking-related subjective norms are positively related to perceived knowledge | −0.15 | 0.01 |

| Perceived seeking control is positively related to perceived knowledge | 0.42 | 0.00 |

| Attitude toward seeking is positively related to perceived knowledge sufficiency threshold | 0.01 | 0.47 |

| Seeking-related subjective norms are positively related to perceived knowledge sufficiency threshold | −0.001 | 0.01 |

| Perceived seeking control is negatively related to perceived knowledge sufficiency threshold | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Perceived knowledge insufficiency is positively related to information-seeking intent | 0.10 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.A.; Wu, Q.L.; Hubbard, K.; Hwang, J.; Zhong, L. Information-Seeking Behavior for COVID-19 Boosters in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2023, 11, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020323

Li XA, Wu QL, Hubbard K, Hwang J, Zhong L. Information-Seeking Behavior for COVID-19 Boosters in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2023; 11(2):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020323

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaoshan Austin, Qiwei Luna Wu, Katharine Hubbard, Jooyun Hwang, and Lingzi Zhong. 2023. "Information-Seeking Behavior for COVID-19 Boosters in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Vaccines 11, no. 2: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020323

APA StyleLi, X. A., Wu, Q. L., Hubbard, K., Hwang, J., & Zhong, L. (2023). Information-Seeking Behavior for COVID-19 Boosters in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines, 11(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020323