Strategic Combination of Theory, Plain Language, and Trusted Messengers Contribute to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: Lessons Learned from Development and Dissemination of a Community Toolkit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. About the Toolkit

2.2. Workbook Content Selection Using Health Behavior Theory

2.3. Workbook Content Development

2.4. Workbook Content Plain Language Assessment

2.5. Workbook Field Testing

2.6. Toolkit Supplementary Materials Development

2.7. Toolkit Dissemination

3. Results

3.1. Toolkit Materials Assessment

3.2. Community Health Worker Survey Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Literacy—Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/health-literacy (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Kutner, M.; Greenburg, E.; Jin, Y.; Paulsen, C.; White, S. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker, Trends in United States COVID-19 Hospitalizations, Deaths, and Emergency Visits by Geographic Area. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklyhospitaladmissions_select_00 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker, Trends in United States COVID-19 Hospitalizations, Deaths, and Emergency Visits by Geographic Area. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklydeaths_select_00 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Mueller, A.L.; McNamara, M.S.; Sinclair, D.A. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect the elderly? Aging 2020, 12, 9959–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, E.M.; Szefler, S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- King, N. Coronavirus Updates. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2021/01/07/954324536/december-was-pandemics-deadliest-month-vaccine-process-has-been-slow (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- COVID Vaccination Insights. Available online: https://nrc.infogram.com/detailed-1220-covid-19-vaccination-insights-oct-dec-2020-1hnq410071n3p23 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social Learning Theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, B.A.; Leath, K.J.; Watson, J.C. COVID-19 consumer health information needs improvement to be readable and actionable by high-risk populations. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.; Toledo, P.; Belton, T.B.; Testani, E.J.; Evans, C.T.; Grobman, W.A.; Miller, E.S.; Lange, E.M.S. Readability, content, and quality of COVID-19 patient education materials from academic medical centers in the United States. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmuda, T.; Özdemir, C.; Ali, S.; Singh, A.; Syed, M.T.; Słoniewski, P. Readability of online patient education material for the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A cross-sectional health literacy study. Public Health 2020, 185, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, N.S.; Ottosen, T.; Fratta, M.; Yu, F. A health literacy analysis of the consumer-oriented COVID-19 information produced by ten state health departments. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2021, 109, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, A.K.; Browne, S.; Srivastava, T.; Kornides, M.L.; Tan, A.S.L. Trusted messengers and trusted messages: The role for community-based organizations in promoting COVID-19 and routine immunizations. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichelt, M.; Cullen, J.P.; Mayer-Fried, S.; Russell, H.A.; Bennett, N.M.; Yousefi-Nooraie, R. Addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in rural communities: A case study in engaging trusted messengers to pivot and plan. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1059067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibe, C.A.; Hickman, D.; Cooper, L.A. To advance health equity during COVID-19 and beyond, elevate and support community health workers. JAMA Health Forum. 2021, 2, e212724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretz, P.J.; Islam, N.; Matiz, L.A. Community health workers and COVID-19—Addressing social determinants of health in times of crisis and beyond. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, D.J.; Gomez, O.; Meraz, R.; Pollitt, A.M.; Evans, L.; Lee, N.; Ignacio, M.; Garcia, K.; Redondo, R.; Redondo, F.; et al. Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) against COVID-19 disparities: Academic-community partnership to support workforce capacity building among Arizona community health workers. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1072808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immunize Arkansas. Vaccine Workshop Toolkits. Available online: https://www.immunizear.org/vaccine-workshop-toolkits (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Tip 6. Use Caution with Readability Formulas for Quality Reports. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/resources/writing/tip6.html (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Kincaid, J.; Fishburne, R.; Rogers, R.; Chissom, B. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Inst. Simul. Train. 1975, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, G.H. SMOG grading: A new readability formula. J. Read. 1969, 12, 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, E. A readability formula that saves time. J. Read. 1968, 11, 513–516. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, S.J.; Wolf, M.S.; Brach, C. The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications2/files/pemat_guide_0.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W.; Castro, K.M.; DeWalt, D.A.; Pignone, M.P.; Mockbee, J.; Hale, F.A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The health belief model as an explanatory framework for communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Gautam, R.K. How well the constructs of the health belief model predict vaccination intention: A systematic review on COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker, COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-booster-percent-total (accessed on 23 May 2023).

| Constructs of the Health Belief Model | Key Messages |

|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility (Perception of disease risk) | Older and minority groups are at an increased at risk of getting a COVID-19 infection. |

| Perceived severity (Perception of the severity of the disease) | COVID-19 infections can cause a range of symptoms, sometimes leading to hospitalization, death, or permanent health problems. Older adults and minorities are at an increased risk of these severe outcomes. No individual can predict how severely a COVID-19 infection will affect them. |

| Perceived barriers (Perception of barriers to getting the vaccine) | The methods for developing and authorizing COVID-19 vaccines were expedited but no steps were skipped in the process. Testing for safety was carried out and included older adults and minorities. COVID-19 vaccines are free for everyone in the United States, regardless of insurance status or U.S. citizenship |

| Perceived benefits (Perception of benefits of getting a vaccine) | Getting a COVID-19 vaccine can protect not only the individual receiving the vaccine but also family and friends. This includes protecting those who are unable to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Getting a COVID-19 vaccine can limit the need to miss work or school, thus supporting financial and academic goals. |

| Survey Question | Survey Response Options |

|---|---|

| What is your practice location type? |

|

| Your Organization/Clinic/Pharmacy Information |

|

| Name of person who used the Workbook (First and Last Name) | (Free Text) |

| Date Workbook was used | (Free Text) |

| Title of person who used the Workbook |

|

| Which language version of the Workbook was used? |

|

| How was the Workbook used? (please complete a separate survey for different uses of the Workbook) |

|

| How many people did you speak with during this event? (an event can be an individual conversation with someone) |

|

| Did using the Workbook help you feel more confident in talking to people about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines? |

|

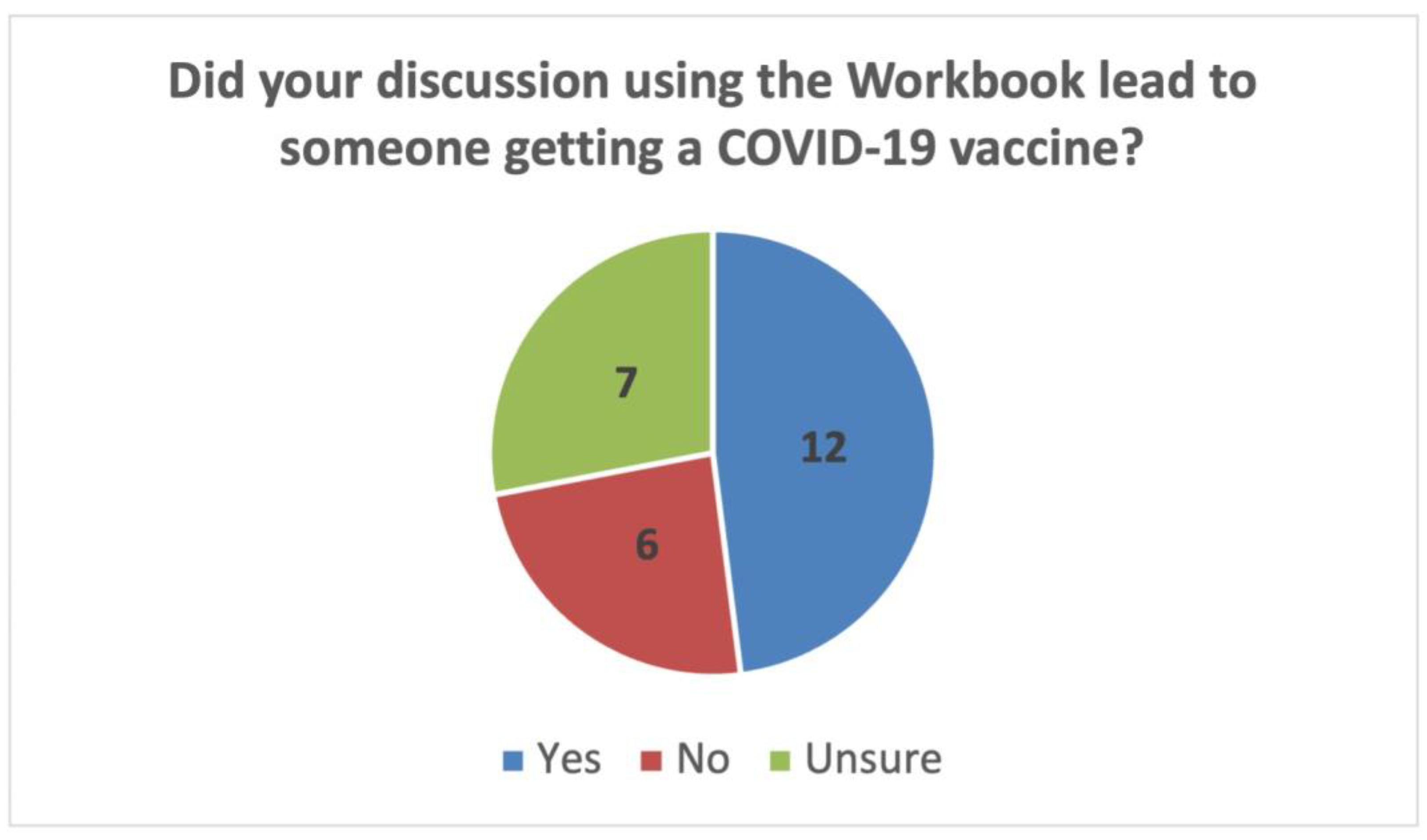

| Did your discussion using the Workbook lead to someone getting a COVID-19 vaccine? |

|

| How many people received a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine after you spoke with them? (please type “0” if no people received a dose after you spoke with them) | (Free text) |

| Were you asked any questions during the event that you felt unprepared to answer? If yes, please specify. |

|

| Do you have any suggestions for improving the COVID-19 Workbook/Toolkit? Please answer honestly if you have a suggestion. We welcome constructive criticism. | (Free text) |

| Success Stories: If you have a specific success story you would like us to know about, please feel free to share it with us. | (Free text) |

| Learning Experience: If you have a specific experience that you learned from and would like us to know about, please feel free to share it with us. | (Free text) |

| Other Comments: If you have other comments for our team, please feel free to share them below. | (Free text) |

| Document Title | Grade Level Readability Range | Level of Difficulty | Pemat-P Understandability Score | Pemat-P Actionability Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Vaccine: Learn the Facts to Stay Safe and Protect Others—Workbook | 4th to 7th | Easy to read | 100% | 100% |

| COVID-19 Vaccine: Learn the Facts to Stay Safe and Protect Others—Leader Guide | 6th to 8th | Average difficulty | 100% | 100% |

| COVID-19 Vaccine: Learn the Facts to Stay Safe and Protect Others—Leader Script | 5th to 8th | Average difficulty | 100% | 100% |

| Learn the Risk of Getting Sick with COVID-19–Data Sheet | 5th to 9th | Average difficulty | 92.3% | 100% |

| Survey Question | Responses (n = 24) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Response Options | Frequency | Percentage | |

| What is your practice location type? | Clinic | 0 | 0% |

| Pharmacy | 12 | 50.0% | |

| AFMC | 12 | 50.0% | |

| Other | 0 | 0% | |

| Title of person who used the Workbook | CHW | 19 | 79.2% |

| Nurse | 0 | 0% | |

| Physician | 0 | 0% | |

| Pharmacist | 3 | 12.5% | |

| Other | 2 | 8.3% | |

| Which language version of the Workbook was used? | English | 23 | 95.8% |

| Spanish | 0 | 0% | |

| Marshallese | 1 | 4.2% | |

| How was the Workbook used? (please complete a separate survey for different uses of the Workbook) * | Individual discussion with someone in the clinic/pharmacy setting | 12 | 50% |

| Individual discussion with someone outside of the clinic/pharmacy setting | 3 | 12.5% | |

| Discussions with people at a community event | 10 | 41.7% | |

| Hosted a COVID-19 Presentation using the Workbook | 3 | 12.5% | |

| Other | 3 | 12.5% | |

| How many people did you speak with during this event (an event can be an individual conversation with someone)? | 1 | 6 | 25% |

| 2 to 5 | 7 | 29.2% | |

| 6 to 9 | 1 | 4.2% | |

| 10 to 19 | 5 | 20.8% | |

| 20 or more | 5 | 20.8% | |

| Did using the Workbook help you feel more confident in talking to people about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines? | Yes | 22 | 91.7% |

| No (please explain) ** | 2 | 8.3% | |

| Did your discussion using the Workbook lead to someone getting a COVID-19 vaccine? | Yes | 12 | 50.0% |

| No | 5 | 20.8% | |

| Unsure | 7 | 29.2% | |

| Were you asked any questions during the event that you felt unprepared to answer? If yes, please specify. | Yes (please explain) | 1 (Not always able to answer extreme conspiracy theory driven questions) | 4.2% |

| No | 23 | 95.8% | |

| Survey Question | Responses (Frequency) | Representative Quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| How many people received a dose of a COVID-19 vaccine after you spoke with them? (please type “0” if no people received a dose after you spoke with them) | 0 (10) 1 (3) 3 (1) 4 (1) 5 (1) 15 (1) 16 (1) 18 (1) 25 (1) Unsure/unknown (4) | N/A |

| Do you have any suggestions for improving the COVID-19 Workbook/Toolkit? Please answer honestly if you have a suggestion. We welcome constructive criticism. | N/A | “I like the workbook. I never had the opportunity to present a class but practiced a lot with it. I think people would be able to easily follow the presentation”. |

| Success Stories: If you have a specific success story you would like us to know about, please feel free to share it with us. | N/A | “Once I have had the discussion of the importance of the vaccine, I have never had anyone turn me down”. |

| Learning Experience: If you have a specific experience that you learned from and would like us to know about, please feel free to share it with us. | N/A | “I learned a lot about the workbook and the motivational aspect on how to be comfortable talking to the community”. |

| Other Comments: If you have other comments for our team, please feel free to share them below. | N/A | “I think the workbook is a great tool. Very easy to use, read and understand. Great information in it”. “Valuable tool and very useful for seminars and educational gatherings”. “I learned a lot with the vaccine webinars. It made me comfortable and happy with talking to the community”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero, A.; Leath, K.J.; Staton, A.D. Strategic Combination of Theory, Plain Language, and Trusted Messengers Contribute to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: Lessons Learned from Development and Dissemination of a Community Toolkit. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061064

Caballero A, Leath KJ, Staton AD. Strategic Combination of Theory, Plain Language, and Trusted Messengers Contribute to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: Lessons Learned from Development and Dissemination of a Community Toolkit. Vaccines. 2023; 11(6):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061064

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero, Alison, Katherine J. Leath, and Allie D. Staton. 2023. "Strategic Combination of Theory, Plain Language, and Trusted Messengers Contribute to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: Lessons Learned from Development and Dissemination of a Community Toolkit" Vaccines 11, no. 6: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061064

APA StyleCaballero, A., Leath, K. J., & Staton, A. D. (2023). Strategic Combination of Theory, Plain Language, and Trusted Messengers Contribute to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: Lessons Learned from Development and Dissemination of a Community Toolkit. Vaccines, 11(6), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061064