Abstract

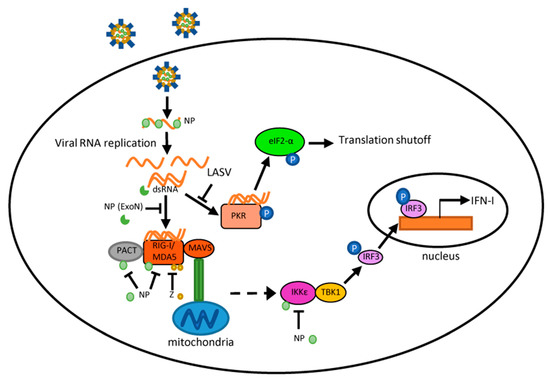

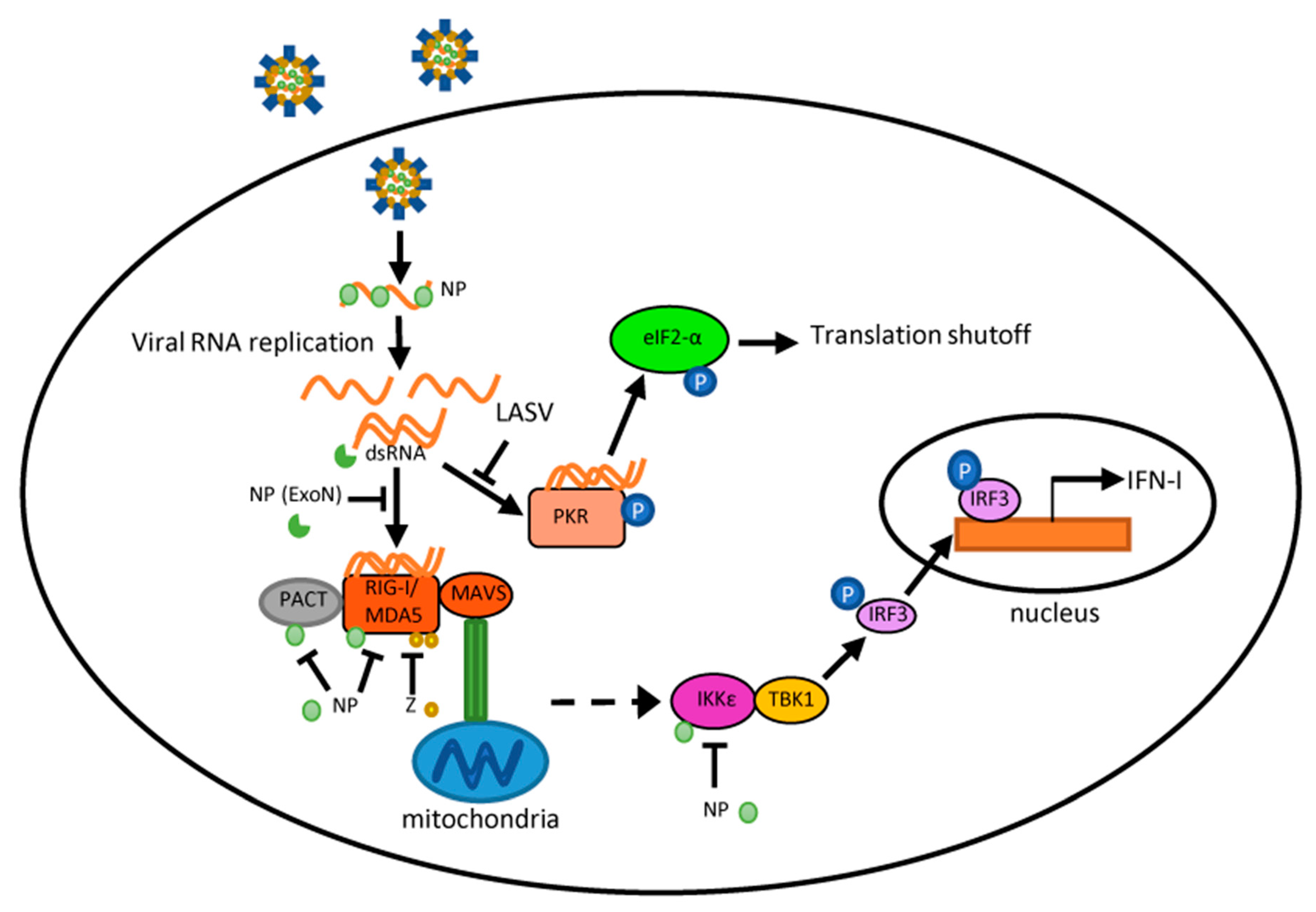

The family Arenaviridae contains several pathogens of major clinical importance. The Old World (OW) arenavirus Lassa virus is endemic in West Africa and is estimated to cause up to 300,000 infections each year. The New World (NW) arenaviruses Junín and Machupo periodically cause hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in South America. While these arenaviruses are highly pathogenic in humans, recent evidence indicates that pathogenic OW and NW arenaviruses interact with the host immune system differently, which may have differential impacts on viral pathogenesis. Severe Lassa fever cases are characterized by profound immunosuppression. In contrast, pathogenic NW arenavirus infections are accompanied by elevated levels of Type I interferon and pro-inflammatory cytokines. This review aims to summarize recent findings about interactions of these pathogenic arenaviruses with the innate immune machinery and the subsequent effects on adaptive immunity, which may inform the development of vaccines and therapeutics against arenavirus infections.

Keywords:

arenavirus; hemorrhagic fever; immunity; interferon; innate sensing; Lassa virus; Junín virus; Machupo virus 1. Introduction

Arenaviruses are enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses [1]. The family Arenaviridae currently consists of four genera, Mammarenavirus, Reptarenavirus, Hartmanivirus, and Antennavirus [2,3]. With the exception of the trisegmented Antennavirus genus, arenavirus genomes are bi-segmented, with one large (L) segment of around 7.2 kb and one small (S) segment of around 3.4 kb. Each segment contains two open reading frames (ORFs) encoding two gene products in opposite orientation, allowing the virus to assume an ambisense coding strategy. The two ORFs are separated by a highly structured intergenic region (IGR) that functions to terminate viral RNA transcription [4]. The conserved termini regions of each genomic segment form pan-handle structures and mediate viral RNA replication and transcription [5,6]. The S segment encodes the viral glycoprotein (GP) precursor, which is post-translationally cleaved into stable signal peptide (SSP) and mature GP1 and GP2 [7,8,9]. All three of these cleaved products form the glycoprotein complex and are incorporated into virions, with GP1 and GP2 forming the spikes on the surface of virions that bind to host receptors and mediate cell entry [10]. The S segment also encodes the nucleoprotein (NP), which is the most abundant viral protein produced during infection and the major structural component of the nucleocapsid [1]. The L segment encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein and a small, zinc finger protein (Z), which acts as the arenavirus matrix protein that drives the assembly and budding of virus particles [11,12,13].

Within the family Arenaviridae, all human pathogens are members of the Mammarenavirus genus [2]. Mammarenaviruses are further separated into two groups based on geography and phylogeny: the Old World (OW) arenaviruses and the New World (NW) arenaviruses [14]. Lassa virus (LASV) is endemic in West Africa and is therefore classified as an OW arenavirus. The prototypic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is also classified as an OW arenavirus based on similar phylogeny [15]. Meanwhile, NW arenaviruses are endemic to South America and can be further divided into four clades (A–D). Clade B contains all the pathogenic NW arenaviruses, including Junín (JUNV) and Machupo viruses (MACV), the causative agents of Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF) and Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), respectively. Notably, clade A contains the prototypic Pichinde virus that, while non-pathogenic to humans, causes hemorrhagic disease in rodents that is similar to Lassa fever (LF) in humans [16,17].

Mammarenavirus (with the exception of Tacaribe virus) are rodent-borne viruses, which usually infect specific rodent species. Therefore, the geographic distribution of each arenavirus is defined by the range of the habitat of its host rodent species. Mastomys natalensis, the reservoir for LASV, is found across much of Africa, though most LASV infections occur in M. natalensis monophylogenetic group A–I in West Africa [18,19]. NW arenaviruses likewise each primarily infect a single species of rodent in the Americas. Arenaviruses often persistently infect their natural hosts without overt disease signs and are shed via excreta from infected animals. The transmission of pathogenic arenaviruses to humans occurs largely through aerosol exposure to rodent excreta or consumption of rodent meat [1,20]. Most infections occur in a rural setting, often during cyclical outbreaks. However, nosocomial transmission of LASV, JUNV, and MACV has been reported [1,21,22].

Within endemic areas, both OW and NW arenaviruses are responsible for significant human disease. Among the highly pathogenic arenaviruses, LASV is the most prevalent and clinically important, with an estimated 100,000–300,000 infections and 5000 deaths in West Africa each year [23]. While most LASV infections are asymptomatic, severe LF can have case fatality rates ranging from 9.3–18% among hospitalized patients [24]. For pathogenic NW arenaviruses (JUNV and MACV), the case fatality rates can be as high as 15–35% [25,26].

In addition to the severe acute disease and high mortality rates in humans, long-term sequelae are common but often neglected among survivors. Patients recovering from AHF and BHF often experience a protracted convalescence period, with hair loss and neurological symptoms such as dizziness and headaches lasting up to several months after the acute infection [1,25,26]. Neurological sequelae have also been reported in LF cases [27]. Recently, the prevalence and impact of LASV-induced hearing loss is becoming increasingly recognized as a significant social and economic burden in affected areas [28]. Approximately 33% of LF survivors develop unilateral or bilateral sudden-onset sensorineural deafness that may be permanent [29]. The exact mechanisms behind the development of long-term sequelae after infection by highly pathogenic arenaviruses remain to be determined, but cell-mediated immunity may be involved. Currently, vaccines and treatments are very limited for these hemorrhagic fever-causing arenaviruses. The World Health Organization has listed LF in the Blueprint list of priority diseases for which there is an urgent need for accelerated research and development.

7. Impacts of the Adaptive Cellular Immune Response on Post-Infection Sequelae

Survivors of pathogenic arenavirus infection often develop post-infection sequelae in the months following the acute stage of illness. Neurological symptoms are common during NW arenavirus infection. This correlates with robust viral replication in neurological tissues as evidenced by high viral titers in the brains of infected animals [52,102]. MACV antigen can also be preferentially detected within neurons [52]. Interestingly, treatment of AHF and BHF with convalescent serum increases the likelihood of developing a long-term neurologic syndrome [43,103]. Whether neurological damage is directly caused by the virus infection or through an immune-mediated mechanism is still unknown.

In LASV infection, accumulating evidence has raised the possibility that the neurological sequelae are likely caused by virus-induced immunological injury. A recent study using NHPs as a model for LASV infection demonstrated that NHP survivors developed pathological findings consistent with autoimmune-associated vasculitis [104]. Two out of three NHP survivors also developed sensorineural hearing loss similar to that observed in human cases. Histopathological examination of the inner ear revealed inflammation of vessels and perivascular tissue at 45 days post-infection, long after the acute infection had subsided. Furthermore, serological analysis revealed that survivors developed elevated C-reactive protein and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, which are indicators of autoimmune disease [104]. These findings in NHPs indicate that hearing loss acquired after LF may be due to chronic inflammation.

Studies using a rodent model of LASV-induced hearing loss have provided further evidence that hearing loss may be caused by a cell-mediated immune response rather than through direct viral damage [105]. STAT1 knockout mice infected by clinical LASV isolates develop sensorineural hearing loss, though IFNαβ/γ receptor knockout mice do not. Interestingly, while LASV antigen can be detected in the inner ears of both types of mice, tissue damage was only observed in the STAT1 knockout mice concomitant with profound CD3-positive lymphocytic infiltration [105]. It would be interesting to determine if depletion of T cells could prevent hearing loss in this model.

One study using guinea pigs as a model for LASV infection determined that anterior uveitis was common during both fatal and nonfatal LASV infections [106]. This ocular inflammation was largely T-cell-mediated. However, low levels of LASV RNA were detected in the eyes of all guinea pigs who succumbed to infection as well as 3 of the 7 survivors. While viral antigen was not detected in the eye during this study [106], immunohistochemical staining has revealed the persistent presence of LASV in the smooth muscle of arteries in both a guinea pig and NHP model of infection, likely contributing to the long-lasting vasculitis [104,107]. Thus, it is currently hypothesized that persistently low levels of LASV replication trigger a chronic activation of the adaptive cellular immune response that leads to long-lasting inflammation.

8. Conclusions

Arenaviruses represent a continuing emerging threat as humans increasingly come into contact with their rodent reservoirs. Data from both clinical and animal model studies demonstrate that pathogenic OW and NW arenaviruses elicit vastly different immune responses, which have implications in viral pathogenesis. LASV infection is characterized by weak or delayed IFN-I/ cytokine induction and T-cell responses, while pathogenic NW arenaviruses (JUNV and MACV) trigger a robust IFN-I and pro-inflammatory cytokine response. Though the mechanisms behind these differences remain poorly defined, several observations have been noted. JUNV and MACV infections activate a variety of PRRs likely through dsRNA accumulation, while LASV seems to evade PRR detection. For all arenaviruses tested so far, arenaviral NP and Z proteins are capable of interfering with PRR activation and blocking innate immune signaling in expression studies. Nevertheless, their activity during viral infection remains to be determined. Differences in the innate immune response likely account for the differences seen in the adaptive response to hemorrhagic fever-causing arenaviruses. Overall, LASV clearance is associated with an early and strong cellular immune response, while recent findings have implicated the cellular immune response as a key contributor to the chronic inflammation and sequelae seen in LF survivors. This has profound implications in LASV vaccine development, particularly for those LASV vaccine candidates that are based on a T-cell response. Protection and recovery from pathogenic NW arenavirus infection are mediated by the humoral response. However, pathogenic NW arenaviruses that invade the immune-privileged central nervous system may evade clearance, which potentially causes neurological sequelae. This knowledge may inform the development of a neutralizing antibody-based therapy to treat AHF and BHF patients. Appreciation of the differential immune response to highly pathogenic NW and OW arenaviruses should facilitate the rational design of targeted therapeutics and vaccines.

Author Contributions

E.M., S.P. and C.H. compiled and wrote the paper.

Funding

C.H. was supported by UTMB Commitment Fund P84373 and UTMB IHII grant P84501. S.P. was supported by Public Health Service grant RO1AI093445 and RO1AI129198.

Acknowledgments

C.H. would like to acknowledge Galveston National Laboratory (supported by the UC7 award 5UC7AI094660) for support of research activity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Buchmeier, M.J.; Bowen, M.D.; Peters, C.J. Arenaviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology; Knipe, H.P., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Wolter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 1791–1827. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, P.; Adkins, S.; Alkhovsky, S.V.; Avsic-Zupanc, T.; Ballinger, M.J.; Bente, D.A.; Beer, M.; Bergeron, E.; Blair, C.D.; Briese, T.; et al. Taxonomy of the order bunyavirales: Second update 2018. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.D.; Chen, X.; Tian, J.H.; Chen, L.J.; Li, K.; Wang, W.; Eden, J.S.; Shen, J.J.; Liu, L.; et al. The evolutionary history of vertebrate rna viruses. Nature 2018, 556, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortorici, M.A.; Albariño, C.G.; Posik, D.M.; Ghiringhelli, P.D.; Lozano, M.E.; Rivera Pomar, R.; Romanowski, V. Arenavirus nucleocapsid protein displays a transcriptional antitermination activity in vivo. Virus Res. 2001, 73, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.J.; Southern, P.J. Sequence heterogeneity in the termini of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus genomic and antigenomic rnas. J. Virol 1994, 68, 7659–7664. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzusch, P.J.; Schenk, A.D.; Rahmeh, A.A.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Bavari, S.; Walz, T.; Whelan, S.P. Assembly of a functional machupo virus polymerase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20069–20074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmeier, M.J.; Oldstone, M.B. Protein structure of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: Evidence for a cell-associated precursor of the virion glycopeptides. Virology 1979, 99, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, O.; ter Meulen, J.; Klenk, H.D.; Seidah, N.G.; Garten, W. The lassa virus glycoprotein precursor gp-c is proteolytically processed by subtilase ski-1/s1p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12701–12705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.; Romanowski, V.; Lu, M.; Nunberg, J.H. The signal peptide of the junín arenavirus envelope glycoprotein is myristoylated and forms an essential subunit of the mature g1-g2 complex. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10783–10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihothram, S.S.; York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Role of the stable signal peptide and cytoplasmic domain of g2 in regulating intracellular transport of the junín virus envelope glycoprotein complex. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5189–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Craven, R.C.; de la Torre, J.C. The small ring finger protein z drives arenavirus budding: Implications for antiviral strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12978–12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djavani, M.; Lukashevich, I.S.; Sanchez, A.; Nichol, S.T.; Salvato, M.S. Completion of the lassa fever virus sequence and identification of a ring finger open reading frame at the l rna 5’ end. Virology 1997, 235, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strecker, T.; Eichler, R.; Meulen, J.; Weissenhorn, W.; Dieter Klenk, H.; Garten, W.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus z protein is a matrix protein and sufficient for the release of virus-like particles [corrected]. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10700–10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, H.; Lange, J.V.; Webb, P.A. Interrelationships among arenaviruses measured by indirect immunofluorescence. Intervirology 1978, 9, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Bào, Y.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Charrel, R.N.; Clawson, A.N.; Clegg, C.S.; DeRisi, J.L.; Emonet, S.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. Past, present, and future of arenavirus taxonomy. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 1851–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Hesse, R.A.; Rhoderick, J.B.; Elwell, M.A.; Moe, J.B. Pathogenesis of a pichinde virus strain adapted to produce lethal infections in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 1981, 32, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Connolly, B.M.; Jenson, A.B.; Peters, C.J.; Geyer, S.J.; Barth, J.F.; McPherson, R.A. Pathogenesis of pichinde virus infection in strain 13 guinea pigs: An immunocytochemical, virologic, and clinical chemistry study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 49, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demby, A.H.; Inapogui, A.; Kargbo, K.; Koninga, J.; Kourouma, K.; Kanu, J.; Coulibaly, M.; Wagoner, K.D.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Peters, C.J.; et al. Lassa fever in guinea: Ii. Distribution and prevalence of lassa virus infection in small mammals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2001, 1, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryseels, S.; Baird, S.J.; Borremans, B.; Makundi, R.; Leirs, H.; Goüy de Bellocq, J. When viruses don’t go viral: The importance of host phylogeographic structure in the spatial spread of arenaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.B. Epidemiology and control of lassa fever. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1987, 134, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Monath, T.P.; Mertens, P.E.; Patton, R.; Moser, C.R.; Baum, J.J.; Pinneo, L.; Gary, G.W.; Kissling, R.E. A hospital epidemic of lassa fever in zorzor, liberia, march-april 1972. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 22, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinebaugh, B.J.; Schloeder, F.X.; Johnson, K.M.; Mackenzie, R.B.; Entwisle, G.; De Alba, E. Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. A report of four cases. Am. J. Med. 1966, 40, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.B.; Webb, P.A.; Krebs, J.W.; Johnson, K.M.; Smith, E.S. A prospective study of the epidemiology and ecology of lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 155, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunther, S.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2004, 41, 339–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enria, D.A.; Briggiler, A.M.; Sánchez, Z. Treatment of argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral. Res. 2008, 78, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Grant, A.; Paessler, S. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 5, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmeier, M.J. Lassa fever: Central nervous system manifestations. J. Trop. Geo. Neurol. 1991, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mateer, E.J.; Huang, C.; Shehu, N.Y.; Paessler, S. Lassa fever-induced sensorineural hearing loss: A neglected public health and social burden. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, D.; McCormick, J.B.; Bennett, D.; Samba, J.A.; Farrar, B.; Machin, S.J.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P. Acute sensorineural deafness in lassa fever. JAMA 1990, 264, 2093–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, N.E.; Walker, D.H. Pathogenesis of lassa fever. Viruses 2012, 4, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Bausch, D.G.; Thomas, R.L.; Goba, A.; Bah, A.; Peters, C.J.; Rollin, P.E. Low levels of interleukin-8 and interferon-inducible protein-10 in serum are associated with fatal infections in acute lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 183, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, S.C.; Saavedra, M.C.; Ceccoli, C.; Falcoff, E.; Feuillade, M.R.; Enria, D.A.; Maiztegui, J.I.; Falcoff, R. Endogenous interferon in argentine hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1984, 149, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levis, S.C.; Saavedra, M.C.; Ceccoli, C.; Feuillade, M.R.; Enria, D.A.; Maiztegui, J.I.; Falcoff, R. Correlation between endogenous interferon and the clinical evolution of patients with argentine hemorrhagic fever. J. Interferon. Res. 1985, 5, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozner, R.G.; Ure, A.E.; Jaquenod de Giusti, C.; D’Atri, L.P.; Italiano, J.E.; Torres, O.; Romanowski, V.; Schattner, M.; Gómez, R.M. Junín virus infection of human hematopoietic progenitors impairs in vitro proplatelet formation and platelet release via a bystander effect involving type i ifn signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baize, S.; Kaplon, J.; Faure, C.; Pannetier, D.; Georges-Courbot, M.C.; Deubel, V. Lassa virus infection of human dendritic cells and macrophages is productive but fails to activate cells. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2861–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Carnec, X.; Reynard, S.; Mateo, M.; Picard, C.; Pietrosemoli, N.; Dillies, M.A.; Baize, S. Lassa virus activates myeloid dendritic cells but suppresses their ability to stimulate t cells. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannetier, D.; Faure, C.; Georges-Courbot, M.C.; Deubel, V.; Baize, S. Human macrophages, but not dendritic cells, are activated and produce alpha/beta interferons in response to mopeia virus infection. J. Virol 2004, 78, 10516–10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Reynard, S.; Carnec, X.; Pietrosemoli, N.; Dillies, M.A.; Baize, S. Non-pathogenic mopeia virus induces more robust activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells than lassa virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, A.K.; Akondy, R.S.; Harmon, J.R.; Ellebedy, A.H.; Cannon, D.; Klena, J.D.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A.; Mehta, A.K.; Kraft, C.S.; et al. A case of human lassa virus infection with robust acute t-cell activation and long-term virus-specific t-cell responses. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1862–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.B.; Marzi, A.; Safronetz, D.; Robertson, S.J.; Feldmann, H.; Best, S.M. Immunobiology of ebola and lassa virus infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Frame, J.D.; Rhoderick, J.B.; Monson, M.H. Endemic lassa fever in liberia. Iv. Selection of optimally effective plasma for treatment by passive immunization. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 79, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Seregin, A.; Huang, C.; Kolokoltsova, O.; Brasier, A.; Peters, C.; Paessler, S. Junín virus pathogenesis and virus replication. Viruses 2012, 4, 2317–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiztegui, J.I.; Fernandez, N.J.; de Damilano, A.J. Efficacy of immune plasma in treatment of argentine haemorrhagic fever and association between treatment and a late neurological syndrome. Lancet 1979, 2, 1216–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, L.E.; Smith, M.A.; Geisbert, J.B.; Fritz, E.A.; Daddario-DiCaprio, K.M.; Larsen, T.; Geisbert, T.W. Pathogenesis of lassa fever in cynomolgus macaques. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baize, S.; Marianneau, P.; Loth, P.; Reynard, S.; Journeaux, A.; Chevallier, M.; Tordo, N.; Deubel, V.; Contamin, H. Early and strong immune responses are associated with control of viral replication and recovery in lassa virus-infected cynomolgus monkeys. J. Virol 2009, 83, 5890–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestereich, L.; Lüdtke, A.; Ruibal, P.; Pallasch, E.; Kerber, R.; Rieger, T.; Wurr, S.; Bockholt, S.; Pérez-Girón, J.V.; Krasemann, S.; et al. Chimeric mice with competent hematopoietic immunity reproduce key features of severe lassa fever. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, C.B.; Ayerra, B.L.; Teyssié, A.R. Interferon response in the guinea pig infected with junín virus. J. Med. Virol 1987, 23, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, R.H.; McKee, K.T.; Zack, P.M.; Rippy, M.K.; Vogel, A.P.; York, C.; Meegan, J.; Crabbs, C.; Peters, C.J. Aerosol infection of rhesus macaques with junin virus. Intervirology 1992, 33, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Smith, S.; Hesse, R.A.; Rhoderick, J.B. Pathogenesis of lassa virus infection in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 1982, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, R.H.; Green, D.E.; Peters, C.J. Effect of immunosuppression on experimental argentine hemorrhagic fever in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 1985, 53, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, T.M.; Shaia, C.I.; Bunton, T.E.; Robinson, C.G.; Wilkinson, E.R.; Hensley, L.E.; Cashman, K.A. Pathology of experimental machupo virus infection, chicava strain, in cynomolgus macaques (macaca fascicularis) by intramuscular and aerosol exposure. Vet. Pathol. 2015, 52, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.M.; Bunton, T.E.; Shaia, C.I.; Raymond, J.W.; Honnold, S.P.; Donnelly, G.C.; Shamblin, J.D.; Wilkinson, E.R.; Cashman, K.A. Pathogenesis of bolivian hemorrhagic fever in guinea pigs. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissenbacher, M.C.; Avila, M.M.; Calello, M.A.; Merani, M.S.; McCormick, J.B.; Rodriguez, M. Effect of ribavirin and immune serum on junin virus-infected primates. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1986, 175, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateer, E.J.; Paessler, S.; Huang, C. Visualization of double-stranded rna colocalizing with pattern recognition receptors in arenavirus infected cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.; Thomsen, A.R. Sensing of RNA viruses: A review of innate immune receptors involved in recognizing rna virus invasion. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2900–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gack, M.U. Mechanisms of rig-i-like receptor activation and manipulation by viral pathogens. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5213–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Gao, C. Regulation of mavs activation through post-translational modifications. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 50, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habjan, M.; Andersson, I.; Klingström, J.; Schümann, M.; Martin, A.; Zimmermann, P.; Wagner, V.; Pichlmair, A.; Schneider, U.; Mühlberger, E.; et al. Processing of genome 5’ termini as a strategy of negative-strand RNA viruses to avoid rig-i-dependent interferon induction. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Kolokoltsova, O.A.; Yun, N.E.; Seregin, A.V.; Ronca, S.; Koma, T.; Paessler, S. Highly pathogenic new world and old world human arenaviruses induce distinct interferon responses in human cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 7079–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Kolokoltsova, O.A.; Yun, N.E.; Seregin, A.V.; Poussard, A.L.; Walker, A.G.; Brasier, A.R.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, B.; de la Torre, J.C.; et al. Junín virus infection activates the type i interferon pathway in a rig-i-dependent manner. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, H.; Moller, R.; Fedeli, C.; Gerold, G.; Kunz, S. Comparison of the innate immune responses to pathogenic and nonpathogenic clade b new world arenaviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, E.; Paessler, S.; Huang, C. Confocal imaging of double-stranded rna and pattern recognition receptors in negative-sense rna virus infection. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.A.; Meurs, E.F.; Esteban, M. The dsrna protein kinase pkr: Virus and cell control. Biochimie 2007, 89, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, A.J.; Williams, B.R. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Kolokoltsova, O.A.; Mateer, E.J.; Koma, T.; Paessler, S. Highly pathogenic new world arenavirus infection activates the pattern recognition receptor protein kinase r without attenuating virus replication in human cells. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.R.; Hershkowitz, D.; Eisenhauer, P.L.; Weir, M.E.; Ziegler, C.M.; Russo, J.; Bruce, E.A.; Ballif, B.A.; Botten, J. A map of the arenavirus nucleoprotein-host protein interactome reveals that junín virus selectively impairs the antiviral activity of double-stranded rna-activated protein kinase (pkr). J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Lan, S.; Wang, W.; Schelde, L.M.; Dong, H.; Wallat, G.D.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 2010, 468, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, K.M.; Kimberlin, C.R.; Zandonatti, M.A.; MacRae, I.J.; Saphire, E.O. Structure of the lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsrna-specific 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2396–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. Structures of arenaviral nucleoproteins with triphosphate dsrna reveal a unique mechanism of immune suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16949–16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Shao, J.; Lan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xing, J.; Dong, C.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. In vitro and in vivo characterizations of pichinde viral nucleoprotein exoribonuclease functions. J Virol. 2015, 89, 6595–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnec, X.; Mateo, M.; Page, A.; Reynard, S.; Hortion, J.; Picard, C.; Yekwa, E.; Barrot, L.; Barron, S.; Vallve, A.; et al. A vaccine platform against arenaviruses based on a recombinant hyperattenuated mopeia virus expressing heterologous glycoproteins. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pythoud, C.; Rodrigo, W.W.; Pasqual, G.; Rothenberger, S.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Arenavirus nucleoprotein targets interferon regulatory factor-activating kinase ikkε. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 7728–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, W.W.; Ortiz-Riaño, E.; Pythoud, C.; Kunz, S.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. Arenavirus nucleoproteins prevent activation of nuclear factor kappa b. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8185–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Di, D.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. Arenaviral nucleoproteins suppress pact-induced augmentation of rig-i function to inhibit type i interferon production. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, K.H.; Lui, P.Y.; Ng, M.H.; Siu, K.L.; Au, S.W.; Jin, D.Y. The double-stranded RNA-binding protein pact functions as a cellular activator of rig-i to facilitate innate antiviral response. Cell Host Microbe. 2011, 9, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, P.; Ramanan, P.; Mire, C.E.; Weisend, C.; Tsuda, Y.; Yen, B.; Liu, G.; Leung, D.W.; Geisbert, T.W.; Ebihara, H.; et al. Mutual antagonism between the ebola virus vp35 protein and the rig-i activator pact determines infection outcome. Cell Host Microbe. 2013, 14, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawaratsumida, K.; Phan, V.; Hrincius, E.R.; High, A.A.; Webby, R.; Redecke, V.; Häcker, H. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the influenza a virus nonstructural proteins ns1 and ns2 during natural cell infection identifies pact as an ns1 target protein and antiviral host factor. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9038–9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, K.L.; Yeung, M.L.; Kok, K.H.; Yuen, K.S.; Kew, C.; Lui, P.Y.; Chan, C.P.; Tse, H.; Woo, P.C.; Yuen, K.Y.; et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus 4a protein is a double-stranded rna-binding protein that suppresses pact-induced activation of rig-i and mda5 in the innate antiviral response. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4866–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, C.; Lui, P.Y.; Chan, C.P.; Liu, X.; Au, S.W.; Mohr, I.; Jin, D.Y.; Kok, K.H. Suppression of pact-induced type i interferon production by herpes simplex virus 1 us11 protein. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13141–13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.C.; Sen, G.C. Pact, a protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase, pkr. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 4379–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.E.; Zorzetto-Fernandes, A.L.; Radoshitzky, S.; Chi, X.; Dallari, S.; Marooki, N.; Lèger, P.; Foscaldi, S.; Harjono, V.; Sharma, S.; et al. Ddx3 suppresses type i interferons and favors viral replication during arenavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. The z proteins of pathogenic but not nonpathogenic arenaviruses inhibit rig-i-like receptor-dependent interferon production. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2944–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I. Z proteins of new world arenaviruses bind rig-i and interfere with type i interferon induction. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Cerny, A.M.; Zacharia, A.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Finberg, R.W. Induction and inhibition of type i interferon responses by distinct components of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9452–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Bowman, J.W.; Jung, J.U. Autophagy during viral infection—A double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, J.S.; Candurra, N.A.; Colombo, M.I.; Delgui, L.R. Junín virus promotes autophagy to facilitate the virus life cycle. J. Virol. 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Vidakovics, M.L.A.; Ure, A.E.; Arrías, P.N.; Romanowski, V.; Gómez, R.M. Junín virus induces autophagy in human a549 cells. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillet, N.; Krieger, S.; Journeaux, A.; Caro, V.; Tangy, F.; Vidalain, P.O.; Baize, S. Autophagy promotes infectious particle production of mopeia and lassa viruses. Viruses 2019, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jounai, N.; Takeshita, F.; Kobiyama, K.; Sawano, A.; Miyawaki, A.; Xin, K.Q.; Ishii, K.J.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S.; Suzuki, K.; et al. The atg5 atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14050–14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, F.; Kobiyama, K.; Miyawaki, A.; Jounai, N.; Okuda, K. The non-canonical role of atg family members as suppressors of innate antiviral immune signaling. Autophagy 2008, 4, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Green, D.R. Autophagy-independent functions of the autophagy machinery. Cell 2019, 177, 1682–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Raulet, D.H.; Moretta, A.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Zitvogel, L.; Lanier, L.L.; Yokoyama, W.M.; Ugolini, S. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 2011, 331, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russier, M.; Reynard, S.; Tordo, N.; Baize, S. Nk cells are strongly activated by lassa and mopeia virus-infected human macrophages in vitro but do not mediate virus suppression. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russier, M.; Reynard, S.; Carnec, X.; Baize, S. The exonuclease domain of lassa virus nucleoprotein is involved in antigen-presenting-cell-mediated nk cell responses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 13811–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauquier, N.; Petitdemange, C.; Tarantino, N.; Maucourant, C.; Coomber, M.; Lungay, V.; Bangura, J.; Debré, P.; Vieillard, V. Hla-c-restricted viral epitopes are associated with an escape mechanism from kir2dl2. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, A.; Saavedra, M.; Mariani, M.; Gamboa, G.; Maiza, A. Argentine hemorrhagic fever vaccines. Hum. Vaccin. 2011, 7, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koma, T.; Patterson, M.; Huang, C.; Seregin, A.V.; Maharaj, P.D.; Miller, M.; Smith, J.N.; Walker, A.G.; Hallam, S.; Paessler, S. Machupo virus expressing gpc of the candid#1 vaccine strain of junin virus is highly attenuated and immunogenic. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Carrion, R., Jr.; Salvato, M.S.; Mansfield, K.; Brasky, K.; Zapata, J.; Cairo, C.; Goicochea, M.; Hoosien, G.E.; Ticer, A.; et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the ml29 reassortant vaccine for lassa fever in small non-human primates. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5246–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Patterson, J.; Carrion, R.; Moshkoff, D.; Ticer, A.; Zapata, J.; Brasky, K.; Geiger, R.; Hubbard, G.B.; Bryant, J.; et al. A live attenuated vaccine for lassa fever made by reassortment of lassa and mopeia viruses. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 13934–13942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbert, T.W.; Jones, S.; Fritz, E.A.; Shurtleff, A.C.; Geisbert, J.B.; Liebscher, R.; Grolla, A.; Stroher, U.; Fernando, L.; Daddario, K.M.; et al. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of lassa fever. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Hutwagner, L.; Brown, B.; McCormick, J.B. Effective vaccine for lassa fever. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6777–6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.; Yun, N.E.; Poussard, A.L.; Smith, J.N.; Smith, J.K.; Kolokoltsova, O.A.; Patterson, M.J.; Linde, J.; Paessler, S. Effect of ribavirin on junin virus infection in guinea pigs. Zoonoses Public Health 2012, 59, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, G.A.; Wagner, F.S.; Scott, S.K.; Mahlandt, B.J. Protection of monkeys against machupo virus by the passive administration of bolivian haemorrhagic fever immunoglobulin (human origin). Bull. World Health Organ. 1975, 52, 723–727. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, K.A.; Wilkinson, E.R.; Zeng, X.; Cardile, A.P.; Facemire, P.R.; Bell, T.M.; Bearss, J.J.; Shaia, C.I.; Schmaljohn, C.S. Immune-mediated systemic vasculitis as the proposed cause of sudden-onset sensorineural hearing loss following lassa virus exposure in cynomolgus macaques. MBio 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, N.E.; Ronca, S.; Tamura, A.; Koma, T.; Seregin, A.V.; Dineley, K.T.; Miller, M.; Cook, R.; Shimizu, N.; Walker, A.G.; et al. Animal model of sensorineural hearing loss associated with lassa virus infection. J. Virol. 2015, 90, 2920–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, J.M.; Welch, S.R.; Ritter, J.M.; Coleman-McCray, J.; Huynh, T.; Kainulainen, M.H.; Bollweg, B.C.; Parihar, V.; Nichol, S.T.; Zaki, S.R.; et al. Lassa virus targeting of anterior uvea and endothelium of cornea and conjunctiva in eye of guinea pig model. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Perry, D.L.; DeWald, L.E.; Cai, Y.; Hagen, K.R.; Cooper, T.K.; Huzella, L.M.; Hart, R.; Bonilla, A.; Bernbaum, J.G.; et al. Persistence of lassa virus associated with severe systemic arteritis in convalescing guinea pigs (cavia porcellus). J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).