A Comparison between 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate and Conventional Suturing for the Closure of Epiblepharon Incision Wounds in Children: A Retrospective Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

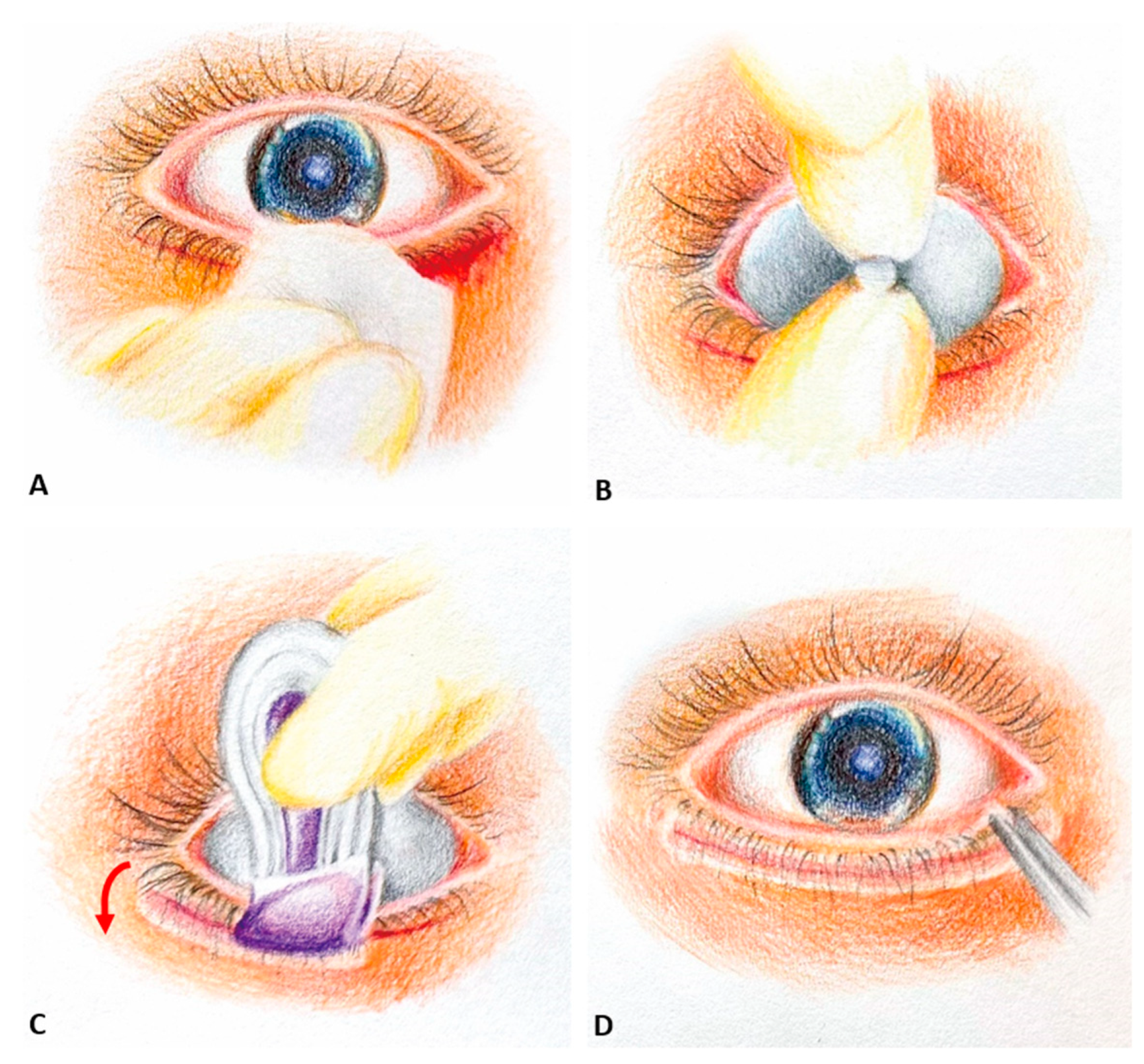

2.1. Technique

2.2. Postoperative Care Instructions

2.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, C.C. Epiblepharon. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1968, 66, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, J.M. Epiblepharon and congenital entropion. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1957, 44, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, G.; Young, S.M.; Tara, S.; Tan, A.M.; Amrith, S. Epiblepharon in East Asian patients: The singapore experience. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.M.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, H.Y. The effect of epiblepharon surgery on visual acuity and with-the-rule astigmatism in children. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 24, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khwarg, S.I.; Lee, Y.J. Epiblepharon of the lower eyelid: Classification and association with astigmatism. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 1997, 11, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quickert, M.H.; Rathbun, E. Suture repair of entropion. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1971, 85, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, D.; Koch, R.J.; Goode, R.L. Efficacy of octyl-2-cyanoacrylate tissue glue in blepharoplasty. A prospective controlled study of wound-healing characteristics. Arch. Facial Plast Surg. 1999, 1, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.Y.; Peponis, V.; Varnell, E.D.; Lam, D.S.; Kaufman, H.E. Preliminary in vitro evaluation of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (dermabond) to seal corneal incisions. Cornea 2005, 24, 998–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farion, K.; Osmond, M.H.; Hartling, L.; Russell, K.; Klassen, T.; Crumley, E.; Wiebe, N. Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, 2002, Cd003326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, S.; Smale, M.; Pacilli, M.; Nataraja, R.M. Tissue adhesive and adhesive tape for pediatric wound closure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 56, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, T.W.; Blyth, K.; Hodgkinson, P.D. Cleft lip repair without suture removal. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2009, 62, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.J.; Hollander, J.E.; Quinn, J.V. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierek, M.; Merkel, K.; Ochała-Gierek, G.; Niemiec, P.; Szyluk, K.; Kuśnierz, K. Which Suture to Choose in Hepato-Pancreatic-Biliary Surgery? Assessment of the Influence of Pancreatic Juice and Bile on the Resistance of Suturing Materials-In Vitro Research. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regula, C.G.; Yag-Howard, C. Suture Products and Techniques: What to Use, Where, and Why. Dermatol. Surg. 2015, 41 (Suppl. S10), S187–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meskin, S.W.; Ritterband, D.C.; Shapiro, D.E.; Kusmierczyk, J.; Schneider, S.S.; Seedor, J.A.; Koplin, R.S. Liquid bandage (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) as a temporary wound barrier in clear corneal cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warder, D.; Kratky, V. Fixation of extraocular muscles to porous orbital implants using 2-ocetyl-cyanoacrylate glue. Ophthalmic. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 31, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslinda, A.R.; Azhany, Y.; Noor-Khairul, R.; Zunaina, E.; Liza-Sharmini, A.T. Cyanoacrylate tissue glue for wound repair in early posttrabeculectomy conjunctival bleb leak: A case series. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2015, 8, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M.; Kitagawa, K.; Yoshida, T.; Koike, C.; Katsumoto, T.; Fujihara, E.; Nikaido, T. Application of 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate for corneal perforation and glaucoma filtering bleb leak. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 7, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, S.H.; Yen, M.T. Octyl-2-cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 21, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.I.; Yi, K.; Kim, Y.D. Surgical correction for lower lid epiblepharon in Asians. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.V.; Drzewiecki, A.E.; Stiell, I.G.; Elmslie, T.J. Appearance scales to measure cosmetic outcomes of healed lacerations. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1995, 13, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñarrocha-Oltra, D.; Candel-Martí, E.; Peñarrocha-Diago, M.; Martínez-González, J.M.; Aragoneses, J.M.; Peñarrocha-Diago, M. Palatal positioning of implants in severely atrophic edentulous maxillae: Five-year cross-sectional retrospective follow-up study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2013, 28, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Dermabond Approval Order. Available online: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf/P960052b.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Sanders, L.; Nagatomi, J. Clinical applications of surgical adhesives and sealants. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 42, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, P.M.; Davis, S.C.; Cazzaniga, A.L.; Drosou, A.; Eaglstein, W.H. Barrier and Antibacterial Properties of 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate-Derived Wound Treatment Films. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2003, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, T.B.; Simon, H.K.; McLario, D.J.; Sullivan, K.M.; Wood, R.J.; Anand, K.J. Laceration repair using a tissue adhesive in a children’s emergency department. Pediatrics 1996, 98, 673–675. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J.V.; Drzewiecki, A.; Li, M.M.; Stiell, I.G.; Sutcliffe, T.; Elmslie, T.J.; Wood, W.E. A randomized, controlled trial comparing a tissue adhesive with suturing in the repair of pediatric facial lacerations. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1993, 22, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, K.L.; Hick, J.L. Preliminary experience with 2-octylcyanoacrylate in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2000, 16, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taravella, M.J.; Chang, C.D. 2-Octyl cyanoacrylate medical adhesive in treatment of a corneal perforation. Cornea 2001, 20, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyniers, R.; Boekhoorn, S.; Veckeneer, M.; van Meurs, J. A case-control study of beneficial and adverse effects of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive for episcleral explants in retinal detachment surgery. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2012, 250, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, B.; Ricci, F. Octyl 2-cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in experimental scleral buckling. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2001, 79, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.K.; Edward, D.; Duffy, M.T. 2-Octyl cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and muscle attachment to porous anophthalmic orbital implants. Ophthalmic. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 17, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perin, L.F.; Helene, A., Jr.; Fraga, M.F. Sutureless closure of the upper eyelids in blepharoplasty: Use of octyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2009, 29, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.; Alejandro-Rodriquez, M.; Perez, E.; Mangel, J. 2-octyl cyanoacrylate skin adhesive for topical skin incision closure in female pelvic surgery. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 5, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Surgiseal Topical Skin Adhesive Approval. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/K161011.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Petrie, E. Cyanoacrylate Adhesives in Surgical Applications. Rev. Adhes. Adhes. 2014, 2, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.P.; Kim, S.D.; Hu, Y.J. Change of visual acuity and astigmatism after operation in epiblepharon children. J. Korean Ophthalmol. Soc. 2001, 42, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Lee, D.S.; Woo, K.I.; Chang, H.R. Changes in astigmatism after surgery for epiblepharon in highly astigmatic children: A controlled study. J. AAPOS 2008, 12, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.B.; Shin, D.M.; Roh, M.S.; Jeung, W.J.; Park, W.C.; Rho, S.H. A comparison of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate adhesives versus conventional suture materials for eyelid wound closure in rabbits. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 25, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahey, A.B.; Gottsch, J.D. Symblepharon associated with cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1993, 111, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strempel, I. Complications by liquid plastics in ophthalmic surgery. Histopathologic study. Dev. Ophthalmol. 1987, 13, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, T.B.; Gottsch, J.D. Infectious keratitis and cyanoacrylate adhesive. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1991, 111, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Huang, D.-W.; Chou, Y.-Y.; An, Y.-C.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Chen, P.-H.; Tzeng, Y.-S. Comparative Evaluation of Tissue Adhesives and Sutures in the Management of Facial Laceration Wounds in Children. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-García, R.F.; Janer, A.L.; Rullán, F.V. Octyl-2-cyanoacrylate liquid bandage as a wound dressing in facial excisional surgery: Results of an uncontrolled pilot study. Dermatol. Surg. 2005, 31, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, S.; Schiestl, C.M.; Landolt, M.A.; Staubli, G.; von Salis, S.; Neuhaus, K.; Mohr, C.; Elrod, J. A Prospective Controlled Study on Long-Term Outcomes of Facial Lacerations in Children. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 616151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmond, M.H.; Klassen, T.P.; Quinn, J.V. Economic comparison of a tissue adhesive and suturing in the repair of pediatric facial lacerations. J. Pediatr. 1995, 126, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Group A | Group B | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 5 | 5 | |

| Female | 5 | 5 | |

| Mean age at operation (years) | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 7.2 ± 4.2 | 0.303 |

| Average body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.97 ± 4.18 | 17.55 ± 4.85 | 0.335 |

| Side of epiblepharon | |||

| Unilateral | 0 | 2 | |

| Bilateral | 10 | 8 | |

| Mean operation time (per eye) (minutes) | 27.6 ± 7.7 | 30.9 ± 10.0 | 0.334 |

| Associated ocular disease (eyes) | |||

| Amblyopia | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | |

| Strabismus | 0 | 2 (4) | |

| Congenital ptosis | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Astigmatism (>1 diopter) | 6 (10) | 8 (15) | |

| High astigmatism (>3 diopter) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Myopia | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | |

| Preoperative BCVA (logMAR) | 0.19 ± 0.21 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.568 |

| Postoperative BCVA (logMAR) | 0.05 ± 0 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.442 |

| Mean follow-up time (months) | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 5.8 ± 6.9 | 0.463 |

| Group A | Group B | Z * | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esthetic outcomes | 9 ± 0.82 | 8.9 ± 0.74 | −0.284 | 0.776 |

| Symptom relief | 9.6 ± 0.52 | 9.5 ± 0.53 | −0.438 | 0.661 |

| Ease of postoperative care | 9.1 ± 0.74 | 6.9 ± 0.99 | −3.629 | <0.001 |

| General satisfaction | 9.1 ± 0.32 | 8.1 ± 0.57 | −3.482 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, C.-C.; Lee, L.-C.; Chang, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsieh, M.-W.; Chien, K.-H. A Comparison between 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate and Conventional Suturing for the Closure of Epiblepharon Incision Wounds in Children: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13123475

Hsu C-C, Lee L-C, Chang H-C, Chen Y-H, Hsieh M-W, Chien K-H. A Comparison between 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate and Conventional Suturing for the Closure of Epiblepharon Incision Wounds in Children: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(12):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13123475

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Chia-Chen, Lung-Chi Lee, Hsu-Chieh Chang, Yi-Hao Chen, Meng-Wei Hsieh, and Ke-Hung Chien. 2024. "A Comparison between 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate and Conventional Suturing for the Closure of Epiblepharon Incision Wounds in Children: A Retrospective Case–Control Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 12: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13123475

APA StyleHsu, C.-C., Lee, L.-C., Chang, H.-C., Chen, Y.-H., Hsieh, M.-W., & Chien, K.-H. (2024). A Comparison between 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate and Conventional Suturing for the Closure of Epiblepharon Incision Wounds in Children: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(12), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13123475