Effectiveness and Safety of Etanercept in Paediatric Patients with Plaque-Type Psoriasis: Real-World Evidence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Medications

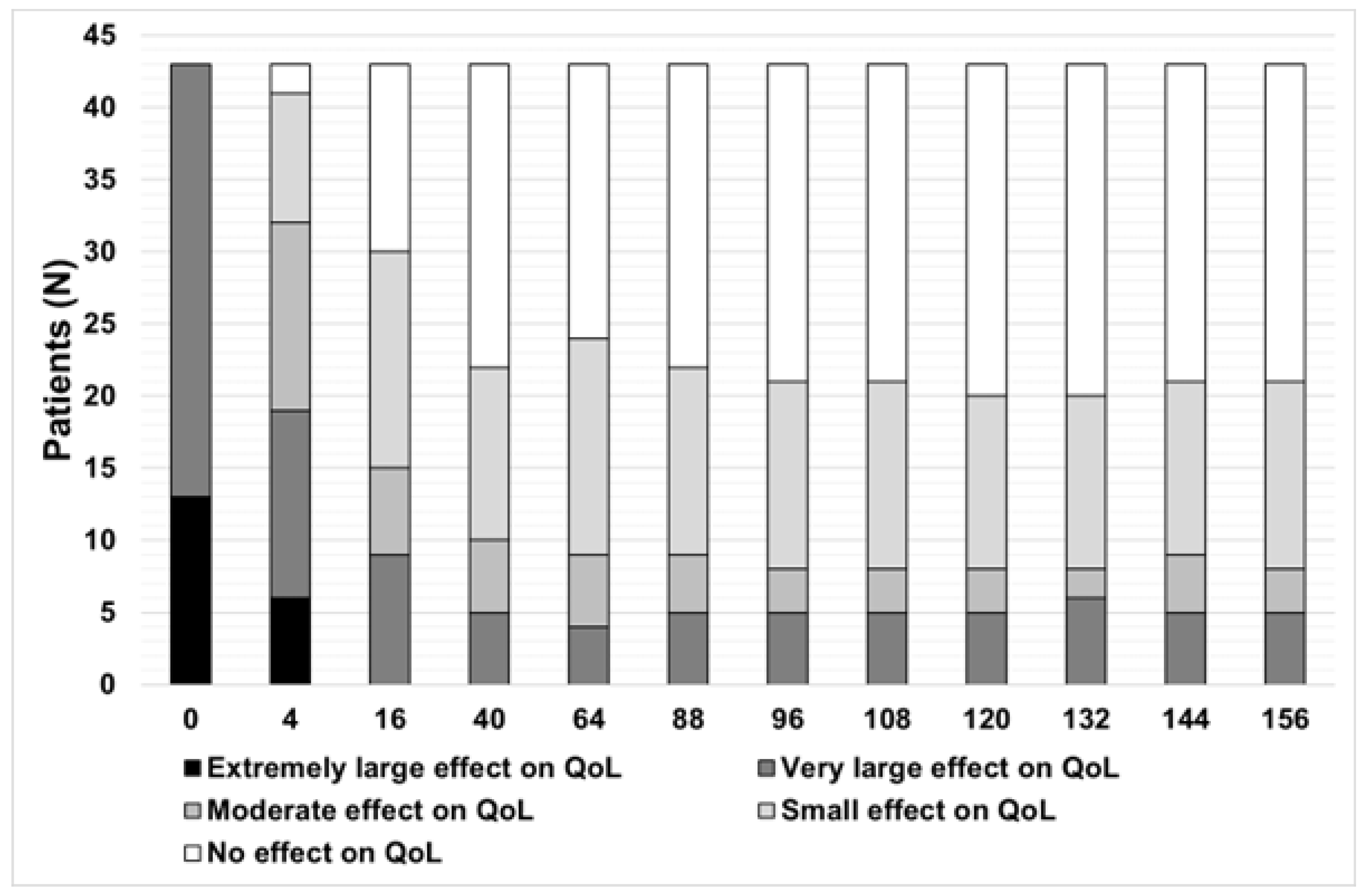

2.2. Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

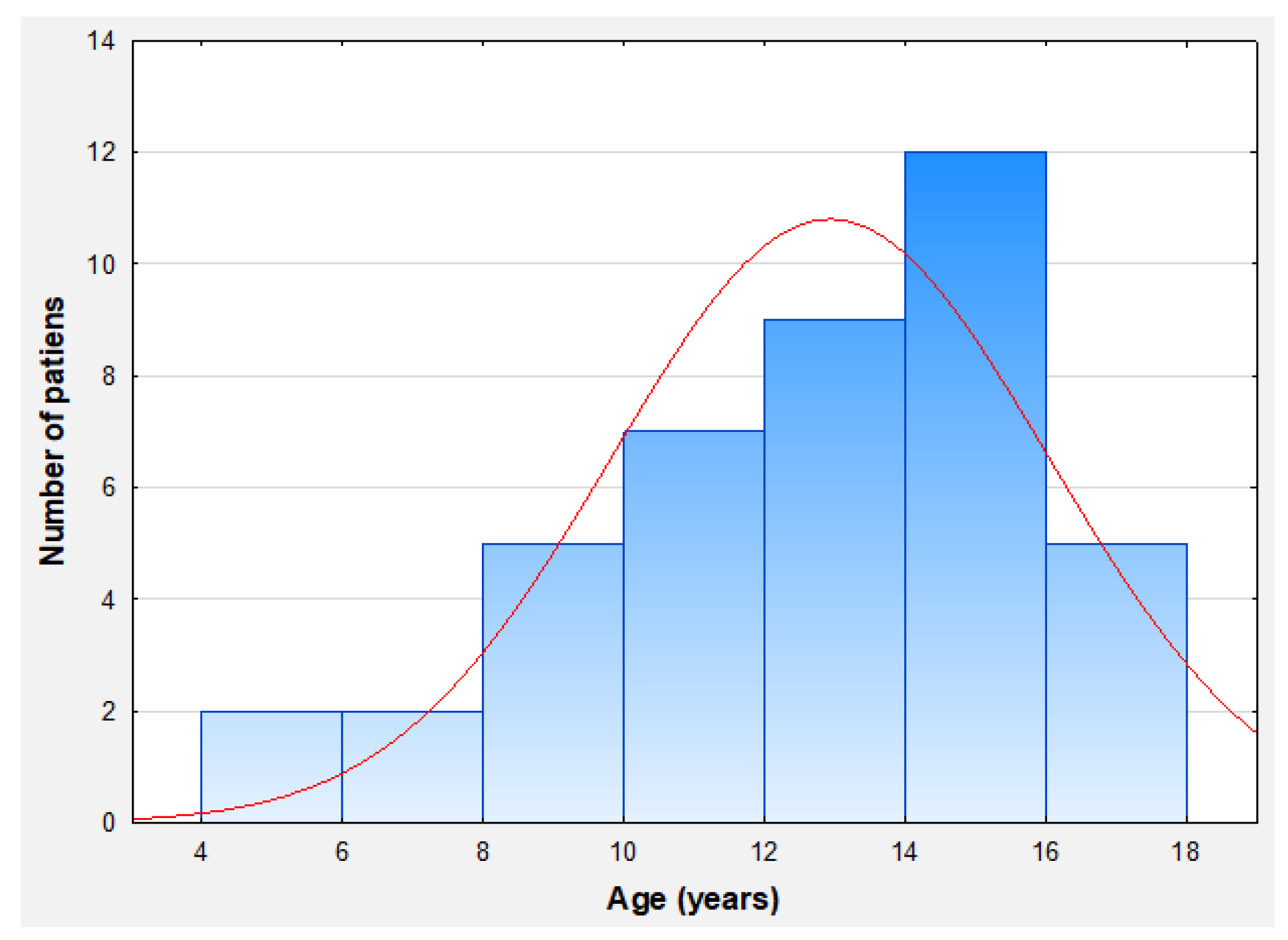

3.1. Patients Characteristics

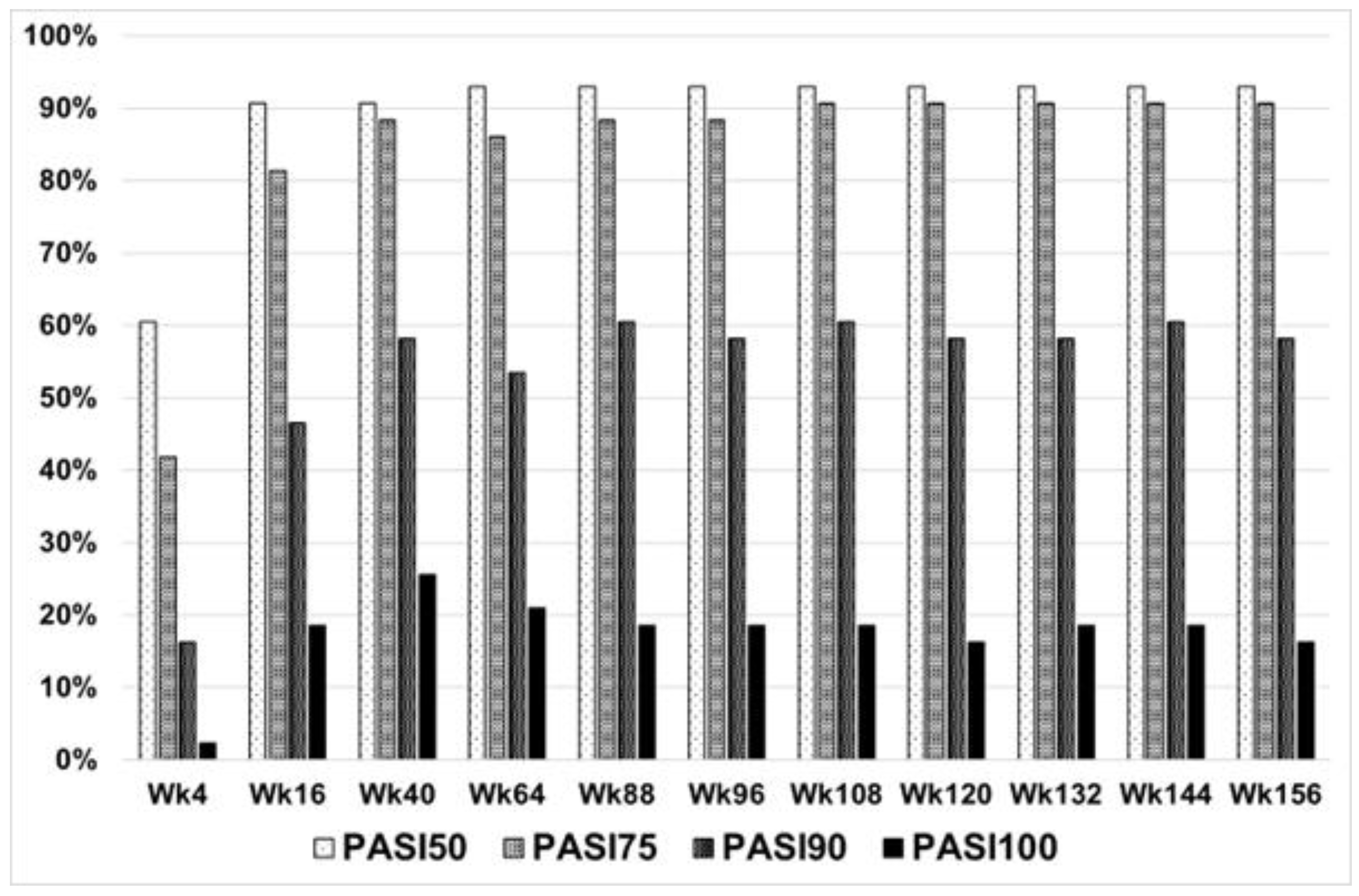

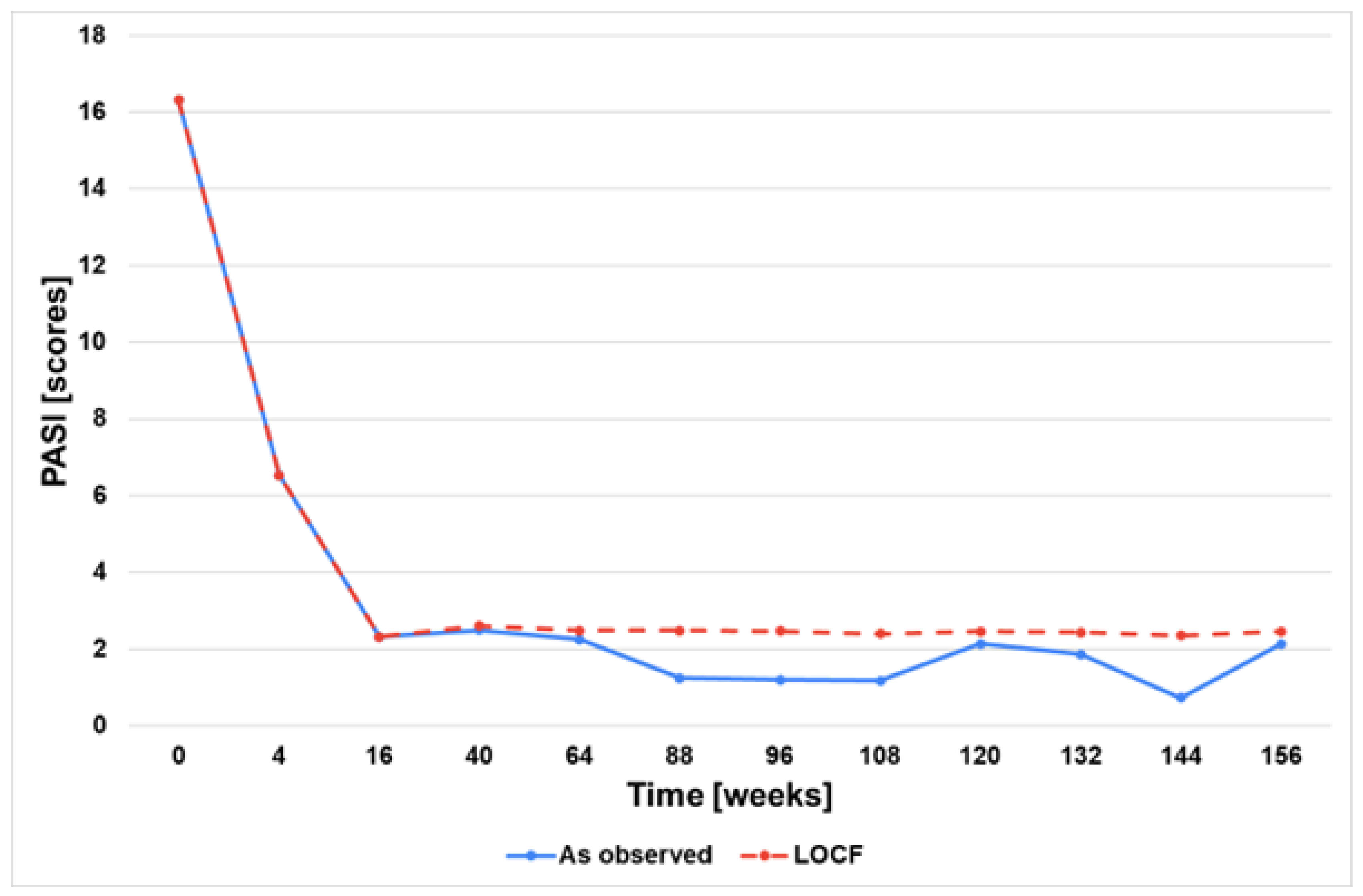

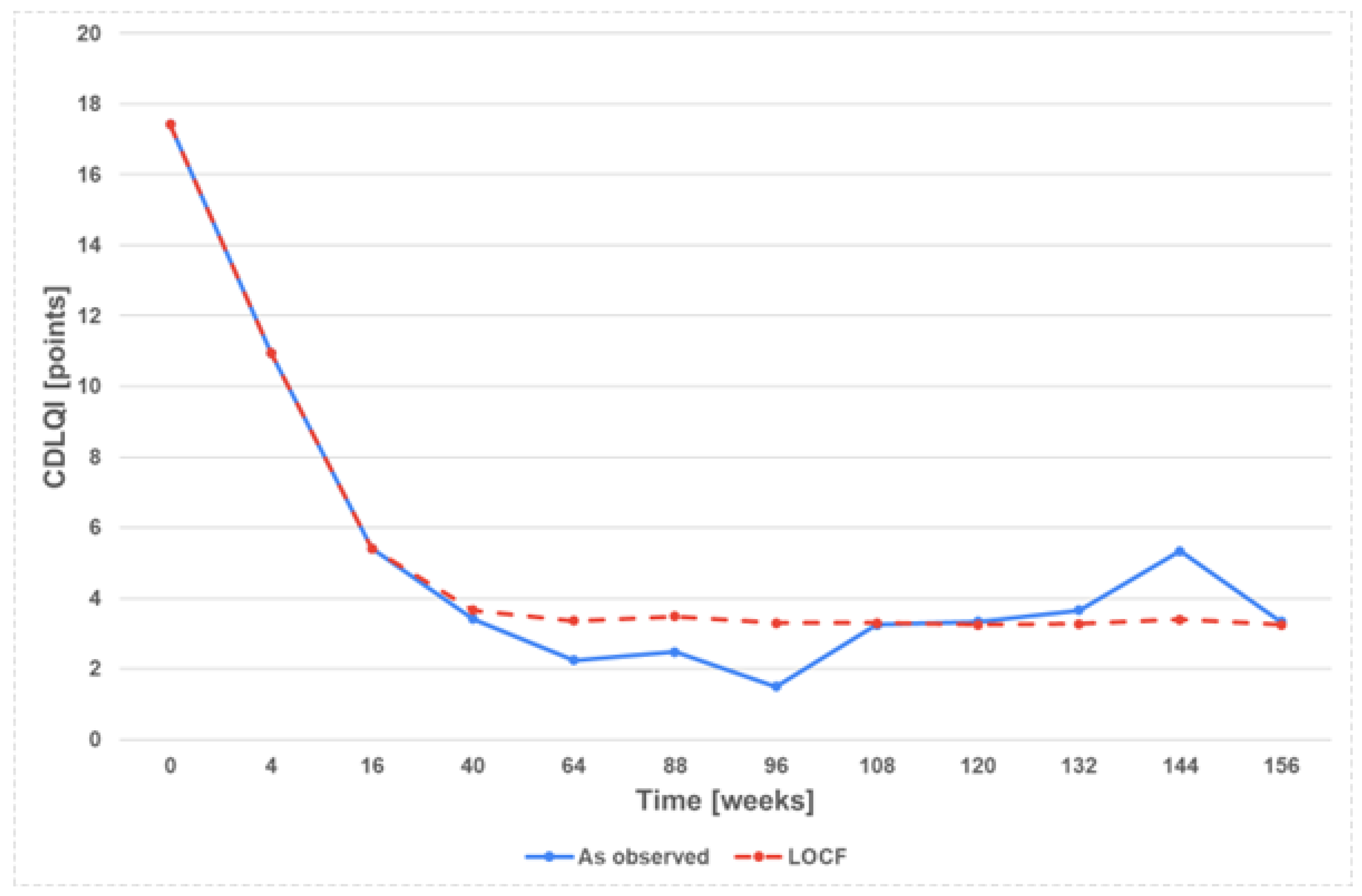

3.2. Effectiveness and Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weigle, N.; McBane, S. Psoriasis. Am. Fam. Physician 2013, 87, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diotallevi, F.; Simonetti, O.; Rizzetto, G.; Molinelli, E.; Radi, G.; Offidani, A. Biological treatments for paediatric psoriasis: State of the art and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.E.; Barker, J.N. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet 2007, 370, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, D.; Sarkar, R.; Podder, I. Parental stress and quality of life in chronic childhood dermatoses: A review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021, 14, S19. [Google Scholar]

- Kivelevitch, D.; Mansouri, B.; Menter, A. Long term efficacy and safety of etanercept in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biologics. 2014, 8, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, J.M.; Weinstein, R.; Porter, S.B.; Neimann, A.L.; Berlin, J.A.; Margolis, D.J. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: A population-based study. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, M.; Glaeske, G.; Radtke, M.A.; Christophers, E.; Reich, K.; Schafer, I. Epidemiology and comorbidity of psoriasis in children. Br. J. Dermat. 2010, 162, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jager, M.E.; Van de Kerkhof, P.C.; De Jong, E.M.; Seyger, M.M. Epidemiology and prescribed treatments in childhood psoriasis: A survey among medical professionals. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2009, 20, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.B.; Lebwohl, M.G. Psoriasis: Which therapy for which patient: Focus on special populations and chronic infections. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.A.; Balogh, E.A.; Kaplan, S.G.; Feldman, S.R. Skin disease in children: Effects on quality of life, stigmatization, bullying, and suicide risk in pediatric acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis patients. Children 2021, 8, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbutt, J.; Reich, A.; Adamski, Z.; Chodorowska, G.; Kaszuba, A.; Krasowska, D.; Lesiak, A.; Maj, J.; Osmola-Mańkowska, A.; Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A.; et al. Psoriasis in children. Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society. Part 1. Dermatol. Rev./Przegl. Dermatol. 2021, 108, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbutt, J.; Reich, A.; Adamski, Z.; Chodorowska, G.; Kaszuba, A.; Krasowska, D.; Lesiak, A.; Maj, J.; Osmola-Mańkowska, A.; Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society. Part 2. Dermatol. Rev./Przegl. Dermatol. 2021, 108, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.47 Drug Programme. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/obwieszczenia-ministra-zdrowia-lista-lekow-refundowanych (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Mocci, G.; Marzo, M.; Papa, A.; Armuzzi, A.; Guidi, L. Dermatological adverse reactions during anti-TNF treatments: Focus on inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2013, 7, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Langley, R.G.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Pariser, D.; Landells, I.; Hebert, A.A.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Patel, V.; Creamer, K.; et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menter, A.; Cordoro, K.M.; Davis, D.M.R.; Kroshinsky, D.; Paller, A.S.; Armstrong, A.W.; Connor, C.; Elewski, B.E.; Gelfand, J.M.; Gordon, K.B.; et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 161–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, A.A.; Browning, J.; Kwong, P.C.; Duarte, A.M.; Price, H.N.; Siegfried, E. Managing pediatric psoriasis: Update on treatments and challenges-a review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/erelzi (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Mrowietz, U.; Kragballe, K.; Reich, K.; Spuls, P.; Griffiths, C.E.; Nast, A.; Franke, J.; Antoniou, C.; Arenberger, P.; Balieva, F.; et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: A European consensus. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Available online: https://www.jakicentyl.pl/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Reich, K.; Burden, A.D.; Eaton, J.N.; Hawkins, N.S. Efficacy of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, N.H.; Betts, K.A.; Soliman, A.M.; Joshi, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Gisondi, P.; Sinvhal, R.; Armstrong, A.W. Comparative safety and benefit-risk profile of biologics and oral treatment for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: A network meta-analysis of clinical trial data. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María Fernández-Torres, R.; Paradela, S.; Fonseca, E. Long-Term Efficacy of Etanercept for Plaque-Type Psoriasis and Estimated Cost in Daily Clinical Practice. Value Health 2015, 18, 1158–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Puya, R.; Gómez-García, F.; Amorrich-Campos, V.; Moreno-Giménez, J.C. Etanercept: Efficacy and safety. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, A.; Esposito, M.; Costanzo, A.; Chimenti, S. Efficacy and safety of etanercept in psoriasis after switching from other treatments: An observational study. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 10, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, K.A.; Bourcier, M.; Poulin, Y.; Lynde, C.W.; Gilbert, M.; Poulin-Costello, M.; Billen, L.; Isaila, M. OBSERVE-5: Comparison of Etanercept-Treated Psoriasis Patients From Canada and the United States. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2018, 22, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lernia, V.; Guarneri, C.; Stingeni, L.; Gisondi, P.; Bonamonte, D.; Calzavara Pinton, P.G.; Offidani, A.; Hansel, K.; Girolomoni, G.; Filoni, A.; et al. Effectiveness of etanercept in children with plaque psoriasis in real practice: A one-year multicenter retrospective study. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2018, 29, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Brinkley, E.; Largent, J.; Sobel, R.E.; Colli, S.; Thaçi, D.; Seyger, M.; Szalai, Z.; Lacour, J.P.; Ståhle, M. A long-term, prospective, observational cohort study of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept for the treatment of patients with paediatric psoriasis in a naturalistic setting. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2023, 33, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, L.; Camacho Martínez, F.M.; Gimeno Carpio, E.; López-Ávila, A.; García-Calvo, C. Efficacy and safety of clinical use of etanercept for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in Spain: Results of a multicentric prospective study at 12 months follow-up. Dermatology 2012, 225, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lümig, P.P.; Driessen, R.J.; Boezeman, J.B.; Van De Kerkhof, P.C.; De Jong, E.M. Long-term efficacy of etanercept for psoriasis in daily practice. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, D.J.; Reiff, A.; Ilowite, N.T.; Wallace, C.A.; Chon, Y.; Lin, S.L.; Baumgartner, S.W.; Giannini, E.H.; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. Safety and efficacy of up to eight years of continuous etanercept therapy in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, D.J.; Reiff, A.; Jones, O.Y.; Schneider, R.; Nocton, J.; Stein, L.D.; Gedalia, A.; Ilowite, N.T.; Wallace, C.A.; Whitmore, J.B.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in children with polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, D.J.; Giannini, E.H.; Reiff, A.; Cawkwell, G.D.; Silverman, E.D.; Nocton, J.J.; Stein, L.D.; Gedalia, A.; Ilowite, N.T.; Wallace, C.A.; et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Pariser, D.M.; Rice, K.C.; Trivedi, M.; Iles, J.; Collier, D.H.; Kricorian, G.; Langley, R.G. Long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 280–287.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Patients | 43 |

|---|---|

| Males | 19 |

| Females | 24 |

| Mean age of inclusion, (SD) | 12.9 (3.1) |

| Range of age | 6–less than 18 years old |

| Mean body weight, (SD) | 61.8 kg (20.8) |

| Males—mean body weight (SD) | 56.8 kg (22) |

| Females—mean body weight (SD) | 56.6 kg (18.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Narbutt, J.; Jakubczak, Z.; Wasiewicz-Ciach, P.; Wojtania, J.; Krupa, K.; Sobolewska-Sztychny, D.; Ciążyńska, M.; Kołt-Kamińska, M.; Reich, A.; Skibińska, M.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Etanercept in Paediatric Patients with Plaque-Type Psoriasis: Real-World Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164858

Narbutt J, Jakubczak Z, Wasiewicz-Ciach P, Wojtania J, Krupa K, Sobolewska-Sztychny D, Ciążyńska M, Kołt-Kamińska M, Reich A, Skibińska M, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Etanercept in Paediatric Patients with Plaque-Type Psoriasis: Real-World Evidence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(16):4858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164858

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarbutt, Joanna, Zofia Jakubczak, Paulina Wasiewicz-Ciach, Joanna Wojtania, Katarzyna Krupa, Dorota Sobolewska-Sztychny, Magdalena Ciążyńska, Marta Kołt-Kamińska, Adam Reich, Małgorzata Skibińska, and et al. 2024. "Effectiveness and Safety of Etanercept in Paediatric Patients with Plaque-Type Psoriasis: Real-World Evidence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 16: 4858. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164858