Abstract

Background: The increased popularity and ubiquitous use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for the treatment of diabetes, heart failure, and obesity has led to significant concern for increased risk for perioperative aspiration, given their effects on delayed gastric emptying. This concern is highlighted by many major societies that have published varying guidance on the perioperative management of these medications, given limited data. We conducted a scoping review of the available literature regarding the aspiration risk and aspiration/regurgitant events related to GLP-1 RAs. Methods: A librarian-assisted search was performed using five electronic medical databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science Platform Databases, including Web of Science Core Collection, KCI Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, and Preprint Citation Index) from inception through March 2024 for articles that reported endoscopic, ultrasound, and nasogastric evaluation for increased residual gastric volume retained food contents, as well as incidences of regurgitation and aspiration events. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full text of articles to determine eligibility. Data extraction was performed using customized fields established a priori within a systematic review software system. Results: Of the 3712 citations identified, 24 studies met eligibility criteria. Studies included four prospective, six retrospective, five case series, and nine case reports. The GLP-1 RAs reported in the studies included semaglutide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide, and exenatide. All studies, except one case report, reported patients with confounding factors for retained gastric contents and aspiration, such as a history of diabetes, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, psychiatric disorders, gastric reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, Parkinson’s disease, dysphagia, obstructive sleep apnea, gastric polyps, prior abdominal surgeries, autoimmune diseases, pain, ASA physical status classification, procedural factors (i.e., thyroid surgery associated with risk for nausea, ketamine associated with nausea and secretions), and/or medications associated with delayed gastric emptying (opioids, anticholinergics, antidepressants, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, DPP-IV inhibitors, and antacids). Of the eight studies (three prospective and five retrospective) that evaluated residual contents in both GLP-1 users and non-users, seven studies (n = 7/8) reported a significant increase in residual gastric contents in GLP-1 users compared to non-users (19–56% vs. 5–20%). In the three retrospective studies that evaluated for aspiration events, there was no significant difference in aspiration events, with one study reporting aspiration rates of 4.8 cases per 10,000 in GLP-1 RA users compared to 4.6 cases per 10,000 in nonusers and the remaining two studies reporting one aspiration event in the GLP-1 RA user group and none in the non-user group. In one study that evaluated for regurgitation or reflux by esophageal manometry and pH, there was no significant difference in reflux episodes but a reduction in gastric acidity in the GLP-1 RA user group compared to the non-user group. Conclusions: There is significant variability in the findings reported in the studies, and most of these studies include confounding factors that may influence the association between GLP-1 RAs and an increased risk of aspiration and related events. While GLP-1 RAs do increase residual gastric contents in line with their mechanism of action, the currently available data do not suggest a significant increase in aspiration and regurgitation events associated with their use and the withholding of GLP-1 RAs to reduce aspiration and regurgitation events, as is currently recommended by many major societal guidelines. Large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) may be helpful in further elucidating the impact of GLP-1 RAs on perioperative aspiration risk.

1. Introduction

The increased popularity and ubiquitous use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for the treatment of diabetes, heart failure, and obesity has led to significant concern for increased risk for perioperative aspiration and regurgitation events, given their most notable side effect of delayed gastric emptying which increases gastric contents [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, the data on the extent of their impact on gastric contents and clinically significant regurgitation and aspiration events remains conflicting. This concern about regurgitation and aspiration is important because regurgitation can lead to aspiration events, which are associated with significant perioperative morbidity and mortality. These complications include acute respiratory failure, multiple organ failure, prolonged and unexpected hospital stays—often requiring intensive care—and even death [11,12,13]. This has led to speculation about whether these medications, many of which have long half-lives on the orders of a week, should be held for prolonged periods of time prior to procedures requiring anesthesia and the potential need to delay elective procedures to mitigate risks associated with aspiration [9,10]. This concern raised by anesthesiologists and other healthcare providers is highlighted by many major societies that have published varying guidance on the perioperative management of these medications [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. This guidance is variable and mostly based on expert opinion and limited evidence. Current guidance on GLP-1 RAs by various societies ranges from no significant changes required in the perioperative management of these medications to an abundance of caution with a low threshold to delay cases. Such delays may significantly impact many overstretched healthcare systems struggling to provide quality patient care in a timely fashion. Thus, there is a need for a comprehensive review of the literature regarding the aspiration risk and aspiration events related to GLP-1 RAs.

Here, we provide the most comprehensive scoping review of the literature to date regarding GLP-1 RAs, particularly semaglutide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, tirzepatide, and exenatide, and their associated risks for patients undergoing anesthesia. We examine the literature on endoscopic, ultrasound, and nasogastric(NGT)/orogastric(OGT) evaluation for increased gastric contents suggestive of increased aspiration risk and increased regurgitation and aspiration events. We also examine confounding factors that may be associated with these findings observed in the studies of GLP1 agonists. This scoping review summarizes the rapidly expanding and sometimes conflicting literature in this area to inform practitioners to optimize clinical decision-making and improve patient safety.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted by a team with expertise in anesthesiology, critical care, and systematic review methodology to ensure a comprehensive review of the existing evidence regarding the use of GLP-1 RAs and their effects on delayed gastric emptying and aspiration risk with the aim to inform and guide clinical practice in the management of patients requiring anesthesia. The review adhered to the review methodology outlined by Grant and Booth and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [31,32]. Of note, a review protocol was published prior to starting our study. Covidence systematic review software (Melbourne, VIC, Australia; https://www.covidence.org) was accessed on 10 March 2024 to import studies and employed throughout the review process for title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction.

The review focused on the impact of GLP-1 RAs on delayed gastric emptying and the risk of aspiration or delayed gastric emptying in adult patients, particularly as able to be assessed by endoscopic evaluation for retained gastric food contents, ultrasound evaluation for aspiration risk, and nasogastric tube (NGT) suctioning of gastric contents to evaluate for high gastric residuals. The aim was to summarize the available literature up to 10 March 2024, to understand (1) how GLP-1 RA therapy influences the risk of delayed gastric emptying and aspiration as evaluated by using evidence obtained from endoscopic, ultrasound, and/or NGT/OGT procedures suggesting elevated gastric food content and/or high residual gastric contents and (2) the reported aspiration and/or regurgitation events and outcomes of patients receiving GLP-1 RAs.

2.1. Search Strategy

A librarian-assisted search was conducted from inception to 10 March 2024, across multiple databases, including PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science Platform Databases, including Web of Science Core Collection, KCI Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, and Preprint Citation Index. This search aimed to cover all relevant literature available up to that date, utilizing a detailed set of keywords and phrases associated with GLP-1 RAs and their potential impact on gastric emptying and aspiration risk. The search strategy used the following terms: (semaglutide OR ‘GLP-1 receptor agonist’ OR ‘GLP-1 agonist’ OR ‘GLP1 receptor agonist’ OR ‘GLP1 agonist’ OR Ozempic OR Wegovy OR Rybelsus OR Saxenda OR Victoza OR Trulicity OR Byetta OR Bydureon OR Adlyxine OR Tanzeum OR liraglutide OR dulaglutide OR exenatide OR lixisenatide OR albiglutide) AND (‘gastric emptying’ OR ‘gastric residual’ OR residual OR aspirated OR suctioned OR ‘residual gastric’ OR residue OR suctioned OR ‘gastric volume’ OR ‘retained gastric content’ OR ‘cross-sectional area’ OR CSA OR ‘ultrasound’ OR aspiration OR aspirated OR regurgitation OR regurgitated). The strategy was designed to capture the broadest range of clinical research available through 10 March 2024 regarding aspiration risk and aspiration/regurgitant events related to GLP-1 RAs.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (1) investigations into the association between GLP-1 RA therapy and the risk of aspiration or delayed gastric emptying in adult patients, specifically through endoscopic, ultrasound, and/or NGT/OGT evaluation for retained gastric food and/or high residual gastric contents; and (2) reported aspiration events of patients taking GLP-1 RAs undergoing anesthesia. Exclusion criteria included articles not in English and formats where original research was not presented (e.g., reviews, editorials without original research, conference proceedings, and abstracts). Communications and editorials presenting case series and reports were included in this review.

2.3. Data Abstraction

Two reviewers (MGC, EAB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified articles to determine eligibility. The same two reviewers then performed full-text reviews, with conflicts resolved by an independent third reviewer (EL). Covidence was customized for this project’s specific aims and tested on a subset of references to ensure uniform application of the criteria noted above. Data extracted included details related to the publication, including authors, year of publication, journal of publication, type of study, patient demographics, confounding factors, details of the GLP-1 RA medication regimen, symptoms present at the time of procedural evaluation, methods and findings related to gastric emptying or aspiration risk (endoscopic, ultrasound, and nasogastric evaluation for increased residual gastric volume retained food contents), details of aspiration and regurgitation events, and any notable outcomes.

3. Results

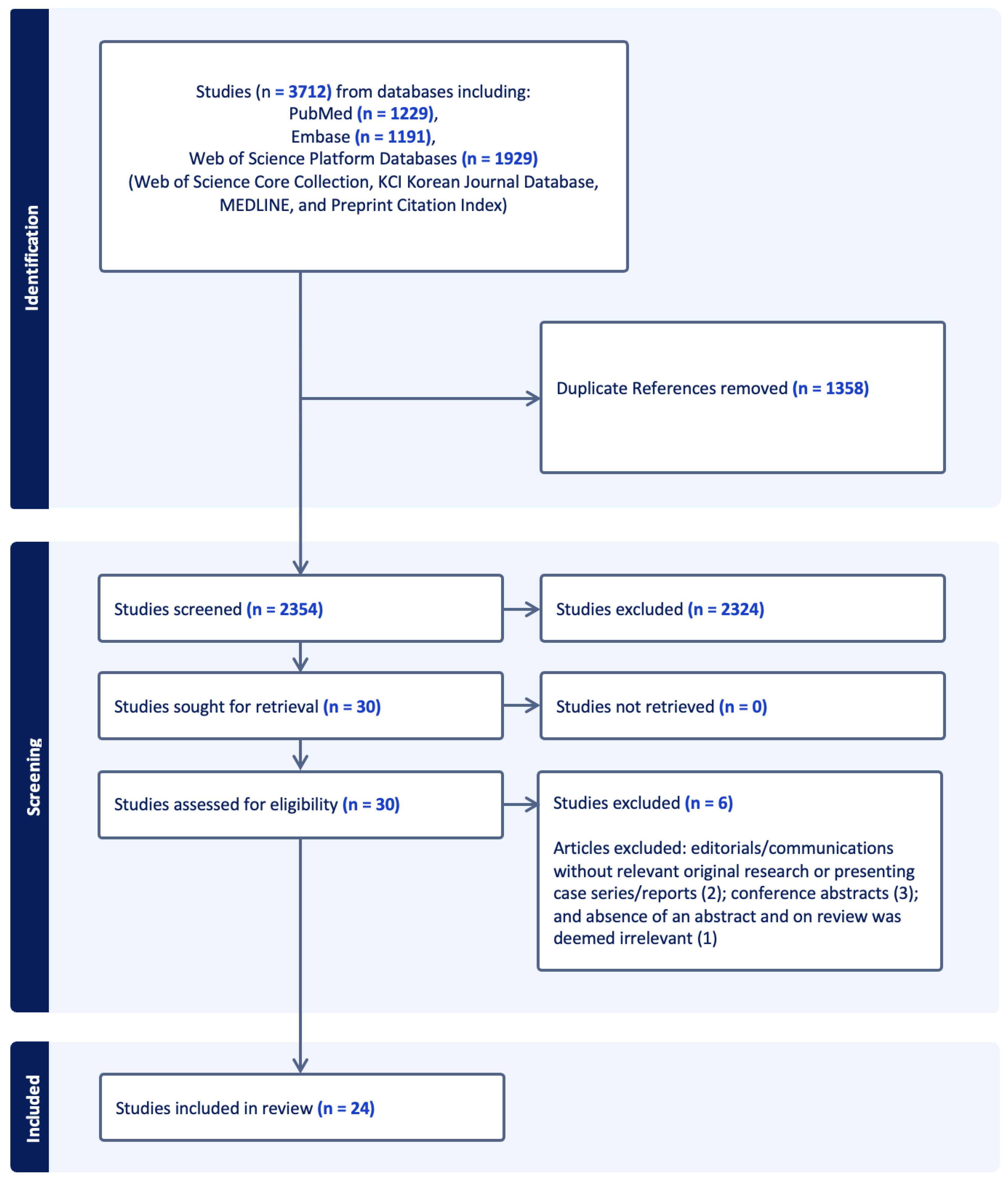

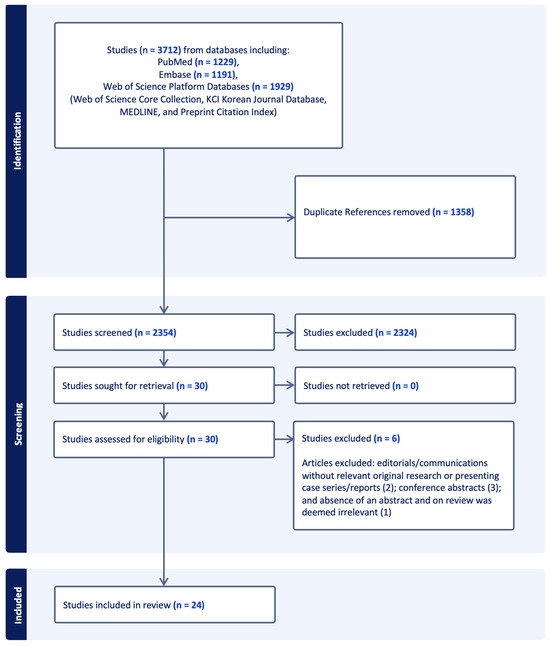

The combination of search terms with selection criteria and limits yielded 3712 articles. Of these articles, 1358 duplicates were removed, leaving 2354 articles for title and abstract screening (Figure 1). Of these, 2324 were excluded for not meeting initial inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in 30 articles for full-text screening. After the full-text screening, 6 articles were excluded (2 excluded given editorial, 1 one was reviewed due to the absence of an abstract and was deemed irrelevant, and 3 were conference abstracts), resulting in 24 articles being included in the final review, comprising 4 prospective studies [33,34,35,36], 6 retrospective studies [37,38,39,40,41,42], 5 case series [43,44,45,46,47], and 9 case reports [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

Figure 1.

Study extraction and inclusion diagram. EMBASE = Excerpta Medica dataBASE.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 24 articles that met inclusion and exclusion criteria, including author, year of publication, study type, patient demographics, confounding factors, details of the GLP-1 RA medication regimen, symptoms present at the time of procedural evaluation, methods and findings related to gastric emptying or aspiration risk, details of aspiration events, and any notable outcomes [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. These studies were published from as early as 2017 to as recently as March 2024, all by separate authors.

Table 1.

Summary of studies with reported endoscopic, ultrasound, and nasogastric evaluation for increased residual gastric volume retained food contents, as well as incidences of regurgitation and aspiration events.

We summarize below in detail the type and scale of studies, confounding factors, GLP-1 agonist holding duration, gastrointestinal symptoms, and endoscopic, ultrasound, and nasogastric evaluation for increased residual gastric volume retained food content, as well as aspiration or regurgitant events and outcomes, reported in these studies and also described in Table 1. The Supplementary Text S1 summarizes the detailed information on these studies found in Table 1 related to age and sex demographics, BMI distribution, medication regimens, medication dosing regimens and durations, indication of GLP-1 RA, and fasting time prior to procedures.

3.1. Types and Scale of Studies

The article included four prospective studies (one randomized, bicentric, investigator-blinded, parallel group prospective study, two prospective observational studies, and one prospective cross-sectional study) [33,34,35,36], six retrospective studies (one retrospective matched pair case-control study, one retrospective cohort study with matched controls, two retrospective observational studies, and two retrospective cohort studies) [37,38,39,40,41,42], five case series [43,44,45,46,47], and nine case reports [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

The size and details of the studies varied significantly across the various types of studies. Of the prospective studies, the cross-sectional study by Sen et al. was the largest prospective study with 124 participants (62 each in GLP-1 RA user and control non-user groups), which compared residual gastric contents measured by gastric ultrasound in GLP-1 RA users and non-user patients presenting for elective surgery, as well as examining the association between duration of interruption of GLP-1 RA and residual gastric contents [35]. Gastric ultrasound was also used to evaluate the effects of GL1-RA on gastric emptying in a study by Sherwin et al., who performed a prospective observational study of 20 volunteer participants (10 on GLP-1 RAs and 10 non-user controls) [36]. Nakatani et al. performed a prospective observational study with 15 patients and investigated the effects of gastric motility using capsule endoscopy prior to and after GLP-1 RA use in patients with diabetes and compared their effects on patients with and without diabetic neuropathy [33]. Quast et al. conducted a randomized, investigator-blinded study with 57 patients involving esophageal manometry studies performed prior to and after starting GLP-1 RAs and reported the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux episodes and pH [34].

Of the retrospective studies, the retrospective, multiple hospital cohort study by Anazco et al. was the largest retrospective study, which assessed the aspiration rate in 2968 unique patients who underwent a total of 4134 endoscopy procedures where GLP-1 RAs were prescribed prior to endoscopies and compared their aspiration rate in GLP-1 RA users to previously published data for non-users [37]. A retrospective study by Bi et al. included a comprehensive cohort of 2150 patients, studying the effects of various medications known to impair gastric emptying (GLP-1 RAs, antacids, cardiovascular medications, and others) on retained gastric food observed on endoscopy [38]. Of note, GLP-1 RAs comprised only a small and unspecified fraction of the patients in the study. A retrospective matched pair case-control study by Kobori et al. involved 1128 individuals, offering an in-depth comparative analysis between the GLP-1 RA and non-user control groups [39]. Additionally, Stark et al. presented findings from a retrospective cohort study with matched controls, comprising 177 individuals (59 patients on GLP-1 RAs and 118 non-user controls), on retained food content and need for gastric lavage or repeat endoscopies due to inadequate visualization on prior endoscopies [41]. Silveira et al. performed a retrospective observational study of 404 patients (33 in the GLP-1 RA group and 371 in the non-user group) that studied gastric residual content volume during endoscopy [40]. Wu et al. performed a retrospective cohort study to assess the residual gastric content on endoscopy of 64 patients on GLP-1 RAs and non-user controls at the time of the endoscopy; the control group patients all started GLP-1 RAs within 1000 days after their endoscopy [42].

The five case series reported were of small size, with one reporting a series of three patients and the other four reporting two patients, including one clinical communication to the editor [43,44,45,46,47]. There were nine case reports included in our review, of which one was a communication to the editor [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

3.2. Confounding Factors

With the exception of the case report by Weber et al. [56], all of the studies (23 of 24) reported confounding factors for the included patients, which included medical conditions, surgical history, medications, and procedural related influences that may be associated with delayed gastric emptying, aspiration, and regurgitation events. These confounding factors included a history of diabetes, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, psychiatric disorders, gastric reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, Parkinson’s disease, dysphagia, obstructive sleep apnea, gastric polyps, prior abdominal surgeries, autoimmune diseases, pain, ASA physical status classification, procedural factors (i.e., thyroid surgery associated with risk for nausea, ketamine associated with nausea and secretions), and/or medications associated with delayed gastric emptying (opioids, anticholinergics, antidepressants, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, DPP-IV inhibitors, and antacids). While all of the retrospective and prospective studies had exclusion criteria that addressed some, but not all, of the confounding factors mentioned above, each study included patients with at least one of these confounding factors [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. The case report by Weber et al. contained limited information regarding the patient’s past medical condition; however, it did specifically note that the patient did not have diabetes [56].

Most studies (19 out of 24) considered diabetes a confounding factor. All prospective and retrospective studies included patients with diabetes and did not exclude all diabetic patients from their GLP-1 RA user group, except for the study by Bi et al., which excluded patients with diabetes from their GLP-1 RA analysis group [38]. In the prospective study by Sherwin et al., which evaluated the effects of GLP-1 RAs on gastric emptying using ultrasound, the GLP-1 agonist group included one patient with diabetes, while the control group had no diabetic patients. Notably, patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyloidosis, and scleroderma were not specifically excluded from the study [36]. Moreover, in the study by Quast et al., which used esophageal pH and manometry to evaluate the frequency and severity of reflux episodes in patients before and after GLP-1 RA treatment, all participants took GLP-1 RAs for type 2 diabetes. The exclusion criteria included patients with decompensated diabetes (hemoglobin A1c > 10%) and those with concomitant diseases associated with severe diabetes, such as liver, renal, and hepatic disease [34]. The prospective study by Nakatani et al. included patients with type 2 diabetes, but the exclusion criteria comprised patients with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes on insulin, and marked dysautonomia [33]. All case series, except for two, included patients with a history of type 2 diabetes. The exceptions were the study by Avraham et al., which included only one of two patients with diabetes, and the study by Raven et al., which featured one patient with a history of esophagitis and hypothyroidism, and another patient with a history of gastric reflux and autoimmune disease [43,44,45,46] All of the case reports included patients with diabetes, except for four studies: Weber et al., Gulak et al., Klein et al., and Espinoza et al. [49,50,51,52,54,55,56] The latter three studies involved aspects of the patients’ medical and medication histories that served as confounding factors. Although the study by Weber et al. did not report any confounding factors, it provided very few details about the patient’s medical history, noting only that the patient had recently started the GLP-1 RA for weight loss and did not specifically have diabetes [56].

3.3. Holding GLP-1 Agonist Duration

Of the four prospective studies, the GLP-1 RA holding time in the two studies by Quast et al. and Sherwin et al. was not specifically mentioned [34,35,36]. In the study by Naktani et al., the GLP-1 RA was not withheld and was taken on the day of the capsule endoscopy [33]. Lastly, in the study by Sen et al., all but 7 of the 62 patients taking GLP-1 RAs had taken the medication within the last 7 days, while the remaining patients withheld their GLP-1 RAs for 8 to 15 days [35].

Of the six retrospective studies, the GLP-1 RA holding time in the study by Silveira et al. was a mean of 10 days, with patients being instructed to hold the GLP-1 RA for 10–14 days. However, some could not follow instructions for various reasons (i.e., last minute notice to fill case cancelation) [40]. The five remaining studies by Kobari et al., Stark et al., Bi et al., Anazco et al., and Wu et al. did not specifically mention the GLP-1 RA holding time, with Wu et al. specifically noting that no instructions were given to patients to withhold GLP-1 RAs prior to the procedure [37,38,39,41,42].

For the five case series, the duration of holding GLP-1 RA was not mentioned in the study by Weber et al. [56]; one patient had their semaglutide for 6 days, and the other patient held their semaglutide for 4 days prior to the procedure in the study by Abraham et al. [43]. One patient only held the oral semaglutide on the morning of surgery, while the other patient had taken his dulaglutide injection in the past week in the study by Wilson et al. [47]. The GLP-1 RA was not held in all three patients taking weekly subcutaneously semaglutide in the study by Kittner et al. [45], and the GLP-1 RA was taken the day before surgery in one patient where solid food was found on initial esophagogastoduodenoscopy (EGD) and then withheld his GLP-1 RA for 3 weeks prior to repeat EGD, which revealed empty stomach, with the other patient with unspecified GLP-1 RA holding time in the study by Raven et al. [46].

Of the nine case reports, the duration of holding the GLP-1 agonist was not mentioned in the five studies by Almustanyir et al., Rai et al., Ishihara et al., Klein et al., and Weber et al. [48,53,54,55,56]. In contrast, four studies by Fujino et al., Gulak et al., Espinoza et al., and Giron-Arango et al. [49,50,51,52] reported that the medication was not withheld and was taken as prescribed. Notably, in the study by Fujino et al., the patient underwent a repeat endoscopy after the initial upper EGD was aborted due to the presence of food residue in the stomach. For the repeat endoscopy, the patient took semaglutide seven days earlier and was instructed to follow a liquid diet for 36 h before the procedure [50].

3.4. GI Symptoms on Presentation

Of the four prospective studies, the gastrointestinal symptoms in the study by Quast et al. were reported to include heartburn, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or loose stools in both patient groups treated with lixisenatide and liraglutide, and no differences between the two groups [34]. The three studies by Sherwin et al., Nakatani et al., and Sen et al. did not evaluate or mention symptoms on the day of the procedure, with the Nakatani et al. study reporting that digestive symptoms induced by liraglutide such as nausea and diarrhea were not severe and did not require discontinuation of the drug in any patients [33,34,35,36]. In the six retrospective studies, gastrointestinal symptoms in the study by Silveira et al. were present in 27.3% of patients in the GLP-1 RA group and 4.5% in the non-user group [40]. In the study by Wu et al., they were present in 12% of patients in the GLP-1 RA group and 2% in the non-user group [42], and they were not specifically mentioned in the four studies by Kobori et al., Stark et al., Bi et al., and Anazco et al., where the indication for endoscopies was not specifically mentioned except in the Stark et al. study, which specifically mentioned that the indications included anemia, gastric reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, dysphagia, abdominal pain, history of gastric polyps, surgical screening, and other [37,38,39,41]. Of the five case series, gastrointestinal symptoms in the two studies by Kittner et al. and Kalas et al. were present and included nausea, vomiting, abdominal bloating, fullness, and/or postprandial epigastric pain [44,45]. The study by Wilson et al. had both patients without gastrointestinal symptoms [47]. The study by Avraham et al. specifically mentioned no nausea and vomiting in one patient and did not specifically mention gastrointestinal symptoms in the other patient [43], and in the study by Raven et al., it was not specifically mentioned. However, one patient’s endoscopy was routine follow-up for esophagitis and the second patient’s indication for endoscopy was reflux [46]. Of the nine case reports, gastrointestinal symptoms—such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, decreased appetite, and weight loss—were present in three studies [48,53,55]. In two studies, these symptoms were specifically reported as absent [50,51,52], and in four studies, gastrointestinal symptoms were not specifically mentioned [49,50,51,54,55,56].

3.5. Endoscopic, Ultrasound, and Gastric Volume Findings

Of the four prospective studies, capsule endoscopy was used to evaluate gastric time in patients prior to and after GLP-1 RAs in one study by Nakatani et al. [33]. Gastric ultrasound was used to assess the effects of gastric emptying in patients taking GLP-1 RAs and control non-users in two studies by Sherwin et al. and Sen et al. [35,36]. There was no evaluation for retained gastric contents or increased gastric residual content by endoscopic, ultrasound and/or nasogastric or orogastric evaluation in the study by Quast et al. [34]. In the study by Nakatani et al., gastrointestinal residue rates were significantly increased post-liraglutide compared prior to starting liraglutide in both the diabetic neuropathy (90.0 ± 9.1% vs. 32.1 ± 24%, p < 0.001) and non-diabetic neuropathy (78.3 ± 23.9% vs. 32.1 ± 35.3%, p < 0.001) groups, while gastric, duodenal, and small intestine transit times were significantly increased after liraglutide administration compared to before starting liraglutide in patients with non-diabetic neuropathy but not in patients with diabetic neuropathy [33]. In the Sherwin et al. study, which involved assessing for solid gastric contents using gastric ultrasound, 70% and 90% of GLP-1 RA participants compared to 10 and 20% of non-user participants in the supine and lateral positions, respectively, showed solid gastric contents after an 8 h fast; participants subsequently had a gastric ultrasound study performed two hours after clear liquid intake which revealed no difference in the lateral position but a significant difference in the supine position, where 90% of controls had an empty stomach compared to 30% of the GLP-1 RA group [36]. On gastric ultrasound imaging, the semaglutide group’s gastric solids were noted to have a layered/yogurt-like consistency. In the study by Sen et al., retained gastric contents evaluated by preprocedural gastric ultrasound were higher in the GLP-1 RA group compared to the non-user group (56% versus 19%), and there was no significant association between the duration of withholding GLP-1 RA and prevalence of retained gastric contents [35]. The study by Quast et al., which did not evaluate for retained gastric contents or increased gastric residual content by endoscopic, ultrasound, and/or nasogastric or orogastric evaluation, involved esophageal pH and manometry studies that evaluated for reflux episode frequency, which is detailed in the following section [34].

Of the six retrospective studies, two found that the occurrence of gastric residue was significantly higher in GLP-1 RA users compared to non-users. Specifically, Kobori et al. reported a prevalence of 5.4% in users versus 0.49% in non-users (p = 0.004), while Wu et al. reported 19% in users compared to 5% in non-users (p = 0.004) [39,40,41,42]. In the study by Silveira et al., the residual gastric content (defined in their study as any amount of solid content, or >0.8 mL/Kg measured from aspiration/suction canister) was higher in GLP-1 RAs users compared to non-users (24.2% vs. 5.1%, p < 0.001) but not the subjective amount of residual gastric contents found on EGD by visual estimation (small, medium, large) [40]. Moreover, the retained gastric content was not statistically significantly higher between the GLP-1 RA users and non-users in the two studies by Stark et al. and Bi et al. Of note, in the latter study, the retained gastric content was found only to be significant on univariate but not multivariate analysis [38,39,40,41]. In the study by Anazco et al., retained gastric contents were not rigorously assessed in the GLP-1 RA user group except in the context of patients with definite pulmonary aspiration events [37]. Notably, in the study by Kobori et al., which found a higher occurrence of gastric residue in GLP-1 RA users compared to non-users, patients with gastric residue were significantly younger and were taking a weekly dose of semaglutide at 1.0 mg. No gastric residue was reported in patients treated with lower doses of liraglutide (≤1.5 mg), lower doses of semaglutide (<0.25 mg), or any dose of oral semaglutide, lixisenatide, or exenatide [39]. In the Wu et al. study, the GLP-1 RA group had 4 of 71 procedures starting as monitored anesthesia care (MAC) with documented residual gastric contents resulting in emergent endotracheal intubation. One of these cases involved a pulmonary aspiration event that led to a transfer to the ICU; the patient was extubated four hours later and discharged the next day. In contrast, no such events were reported in the non-user group [42]. The Stark et al. study, which found that retained gastric content was not statistically different between GLP-1 RA users and non-users, also found that there was no difference in the necessity to perform gastric lavage and undergo a repeat EGD due to inadequate visualization in the GLP-1 RA users compared to non-users [41]. In the Silveira et al. study, propensity weighted analysis revealed increased risk for residual gastric contents with factors such as the use of semaglutides (Prevalence Ratio (PR) = 5.15, 95% CI (1.92–12.92), p < 0.001), preoperative digestive symptoms (including nausea/vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal distension) (PR = 3.56. 95% CI 2.25–5.78, p < 0.001), semaglutide use and digestive symptoms (PR = 16.5, 95% CI 9.08–34.91, p < 0.001), semaglutide use and no digestive symptoms (PR = 9.68, 95% CI 5.6–17.66, p < 0.001), and no semaglutide use and digestive symptoms (PR = 4.94, 95% CI 1.32–15.77, p = 0.0098), while patients undergoing both EGD and colonoscopy showed a protective effect against residual gastric contents (PR = 0.25, 95% CI 0.16–0.39, p < 0.001) [40]. In the same study by Silveira et al., while the pre-endoscopy digestive symptoms were associated with increased retained gastric contents, the duration of preoperative semaglutide cessation did not impact the presence or absence of retained gastric content [40]. In the study by Anazco et al., which did not rigorously assess gastric residues except in the context of two confirmed pulmonary aspiration events among the 4134 reviewed endoscopic procedures following GLP-1 RA prescriptions, one of the patients with an aspiration event was found to have retained food content in the stomach and duodenum during an upper endoscopy performed under monitored anesthesia care (MAC). The other patient who experienced an aspiration event was noted to have ectasia with bleeding and subsequently underwent argon plasma coagulation (APC) [37].

Of the five case series studies, endoscopy revealed solid food in two patients in the study by Raven et al., with one of the patients in the same study having a repeat endoscopy that revealed an empty stomach after holding their GLP-1 RA for 3 weeks and fasting for 12 h [46]. An endoscopy revealed no obstruction in two patients presenting with gastrointestinal side effects consistent with gastroparesis in the study by Kalas et al. [44]. Gastric ultrasound revealed all three patients with residual solid food for patients presenting for orthopedic procedures (also mentioned data from same institution where seven out of eight patients presenting for non-orthopedic procedures had retained solid food on ultrasound evaluation) in the study by Kittner et al. [45], and there was no mention of endoscopic, ultrasound, or gastric findings in the two studies by Wilson et al. and Avraham et al., with the latter study by Avraham et al. reporting nasogastric suctioning following regurgitant epsidoes in two patients without reporting the actual gastric volume suctioned [43,44,45,46,47]. Of note, in the Kalas et al. study, both patients reported gastrointestinal side effects consistent with gastroparesis and had symptom resolution and normalization of the gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) studies after their GLP-RA agonist was held for 4–6 weeks [44].

Of the nine case reports, the five of the case reports by Almustanyir et al., Rai et al., Fujino et al., Ishihara et al., and Klein et al. involved endoscopies, of which two of the studies, by Rai et al. and Ishihara et al., had NGTs placed prior to the procedures with reported residuals [48,49,50,53,54,55]. Two of the case reports by Gulak et al. and Weber et al. reported gastric residuals measured by orogastric tube placed following an aspiration and/or regurgitant episode under anesthesia [52,53,54,55,56]. The case report by Giron-Arango et al. reported increased gastric volumes assessed by gastric ultrasound consistent with full stomach [51], and the case report by Espinoza et al. did not assess gastric residuals using ultrasound or nasogastric tube in this patient presenting for ECT [49]. Of the five studies that reported endoscopic findings, three studies, by Alustanyir et al., Rai et al., and Ishihara et al., reported no obstructing lesion [48,53,55], and the two studies by Fujino et al. and Klein et al. revealed food residue in the stomach, with the study by Fujino et al. leading to abortion of EGD and a repeat EGD a month later with no food residue after a prolonged 36 h liquid fast and patient having taken their semaglutide 7 days prior [50,51,52,53,54]. Of the two studies by Rai et al. and Ishihara et al., which had NGTs placed prior to the procedures, the reported suctioned gastric residuals were 1 L and 600 mL, respectively [53,54,55]. Of the two studies which reported gastric residuals following an orogastric tube placed after an aspiration and/or regurgitant episode under anesthesia, the reported residual amounts were minimal in the study by Gulak et al. and increased (750 mL) in the study by Weber et al. [52,53,54,55,56]. Of the three studies by Almustanyir et al., Rai et al., and Ishihara et al., which reported gastrointestinal symptoms, all four patients had resolution of their symptoms with conservative management, which included discontinuation of the GLP-1 RA, NGT placement, antiemetics, and/or prokinetic medications [48,49,50,51,52,53,55].

3.6. Aspiration or Regurgitant Events and Outcomes

Of the four prospective studies, the study by Quast et al. revealed that regurgitant events as evaluated by reflux episode frequency and severity, as well as esophageal motility and lower esophageal sphincter functionality using esophageal pH and manometry, were not significantly different between GLP-1 agonist users and non-users despite gastric emptying as evaluated by octanoate acid breath test being more significantly prolonged in the GLP-1 agonist user group compared to the non-user group [34]. In the other three studies, by Nakatani et al., Sherwin et al., and Sen et al., aspiration or regurgitant events were not applicable given that the primary interventions or evaluations were capsule endoscopy (Nakatani et al.) or gastric ultrasound (Sherwin et al. and Sen et al.), and the patients did not receive anesthesia [33,35,36].

Of the six retrospective studies, the three studies by Kobori et al., Stark et al., and Bi et al. did not specifically mention aspiration or regurgitation events [38,39,41]. One study by Anazco et al. reported an aspiration rate of 4.8 cases per 10,000 endoscopies in patients after GLP-1 prescription compared to 4.6 cases per 10,000 endoscopies reported previously in patients presenting for elective endoscopies from 2000 to 2016 using the same previously validated automatic search algorithm of the electronic medical record system by Bohman et al. [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. One study by Wu et al. reported one case of pulmonary aspiration in the GLP-1 RA group (total of 90 procedures from 64 patients) and none in the control group (total of 102 procedures from 69 patients) consisting of patients undergoing endoscopies [42], and the study by Silveira et al. reported one case (0.24%) of pulmonary aspiration under deep sedation in patients undergoing elective endoscopies [40]. For the studies by Anazco et al., Wu et al., and Silveira et al., which reported aspiration events, the patient characteristics and outcomes following the aspiration event were reported as follows [37,40,42]. In the study by Anazco et al., the two aspiration events occurred in one patient who was a 47-year-old woman, ASA III, with normal weight, on dulaglutide (3.0 mg weekly, started 30 months ago) for diabetes (HbA1c 6.7) and who had an upper endoscopy for abdominal pain and diarrhea to rule out celiac disease and was found to have retained food contents in the stomach and duodenum during upper endoscopy, had massive vomiting upon scope removal with direct visualization of aspirated contents in the airways and chest imaging compatible with aspiration, and required intubation, ICU admission for 3 days, and vasopressors and was discharged from the hospital after 5 days with oxygen. The other patient was a 72-year-old woman, ASA III, with obesity (class II) and GERD, taking semaglutide (0.5 mg weekly, started 3 months ago) for obesity and had no symptoms on initiation of GLP-1 RA. She had presented for upper endoscopy for iron deficiency anemia and possible GAVE and was found to have diffuse gastric antral vascular ectasia and bleeding requiring APC; she did not have visualization of retained food contents in stomach and duodenum, had persistent hypoxemia after the procedure with imaging compatible with aspiration, did not require ICU admission, and was discharged home after 8 days of hospitalization [37]. In the study by Wu et al., the past medical history and comorbidities of the one patient in the GLP-1 RA group who aspirated was a 42-year-old man with obesity (BMI 37), prior history of Barrett’s esophagus on PPI and histamine receptor agonist, OSA on CPAP, mixed anxiety and depressive disorder on medications with anticholinergic effects (paroxetine), and prior history of lung abscess likely secondary to aspiration in the setting of heavy alcohol use (now sober for 4 years), who had fasted for more than 18 h, with the last dose of GLP-1 RA and gastrointestinal symptoms not reported. He had a pulmonary aspiration event which resulted in emergent intubation and bronchoscopy, revealing food remains in trachea and bronchi; he was transferred to the ICU, extubated 4 h later, and discharged the following day [42]. In the study by Silveira et al., the one reported patient who aspirated in the GLP-1 RA group was a 63-year-old man with obesity (BMI 37.7), prior history of gastric bypass, and semaglutide use (last taken 11 days prior), who had adequately fasted (12.4 h for solids and clear fluids) and reported no digestive symptoms prior to his endoscopy and was not specifically reported to have any negative sequelae following his aspiration event [40].

Of the five case series, two studies by Wilson et al. and Avraham et al. both described two patients who had regurgitant or aspiration events in the perioperative period [43]. One study by Kittner et al. reported postponing the cases of three patients presenting for orthopedic surgery after gastric ultrasound revealed solid food residue [45]. Two studies by Raven et al. and Kalas et al. did not specifically mention an aspiration or regurgitant event during upper endoscopies which revealed residual gastric food content in the Raven et al. study and an absence of obstruction and no specific mention of residual gastric content in the study by Kalas et al. [44,45,46]. In the study by Wilson et al., which described two patients who had regurgitant or aspiration events in the perioperative period, one patient developed orpharyngeal secretions and labored respirations after regional anesthesia and monitored anesthesia care for foot arthrodesis with fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, and ketamine and, following intubation, had significant bilious particulate matter suctioned from the oropharynx and was discharged after 2 h in recovery; the other patient had projectile vomiting with bile-tinted particulate matter following extubation after a thyroidectomy and was discharged the following day per protocol for thyroidectomy procedures [47]. In the study by Avraham et al., one patient had a large volume of regurgitant contents with particular food noted during laryngoscopy following RSI for ERCP, with bilateral infiltrates noted on CXR, and required transfer to ICU, was extubated the following day, and was discharged from the hospital after a week; the other patient had regurgitation of solids and liquids following LMA removal after completion of surgery for I&D of breast abscess, with head tilted and suctioned, rapid sequence intubation, and then extubation awake, and was then transferred to the PACU, with reportedly normal CXR and observation that was normal [43].

Of the nine case reports, an aspiration or regurgitant event was not specifically mentioned in the five studies by Giron-Arango et al., Amustanyir et al., Rai et al., Ishihara et al., and Kobori et al. [39,48,51,53,55], and was noted to not have occurred in two studies, one by Fujino et al. after food residue was found in the stomach during upper endoscopy and the procedure was aborted, and another study by Espinoza et al., where ECT was performed after a risk and benefit discussion with a patient who had last taken his semaglutide days prior [49,50]. Regurgitation or aspiration was noted to have occurred in the three studies by Gulak et al., Klein et al., and Weber et al., where the patients underwent procedures under anesthesia [52,54,56]. The patient in the Gulak et al. case report regurgitated 200 mL of clear fluid after 30 s of gentle mask ventilation following induction of anesthesia; a fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed no evidence of aspiration and an orogastric tube placed prior to extubation had minimal output [52]. Klein et al. reported a large volume solid and liquid aspiration event during an upper endoscopy; fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed food remains in the trachea and bronchi. Of note, this was the only aspiration event that was noted in the retrospective study by Wu et al. [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. In the study by Weber et al., a large volume of gastric aspirate was noted in the oropharynx after supraglottic airway placement for hysterscopy procedure, necessitating tracheal intubation, and orogastric tube placed afterwards revealed approximately 750 cc undigested food and gastric contents [56]. All of the patients reported by Gulak et al., Klein et al., and Weber et al. who had large volume regurgitant or aspiration events were discharged home the following day (of note, they were 42M, 48F, and 59F), with the patient in the Klein et al. study requiring ICU admission [52,54,56].

4. Discussion

We present the first comprehensive scoping review of the impact of GLP-1 RA on the incidence of retained gastric food contents or high gastric residuals assessed by endoscopic, ultrasound, nasogastric and/or orogastric evaluation, as well as reported regurgitation and aspiration events. This review includes findings from a diverse array of studies, including four prospective studies [33,34,35,36], six retrospective studies [37,38,39,40,41,42], five case series [43,44,45,46,47], and nine case reports [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], to synthesize the best available evidence and clinical implications of GLP-1 RA use in patients requiring anesthesia. The majority of the studies were case reports and case series with small sample sizes and low-quality evidence, and many of the studies had significant uncontrolled confounding factors that made it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. From the higher quality of evidence provided by prospective and retrospective studies included in this review, there appears to be insufficient evidence that GLP-1 RAs are consistently associated with an increased incidence of retained gastric contents or regurgitation and aspiration events in the patient populations studied.

It is interesting to note that GLP-1 RAs have been FDA-approved since 2005 for diabetes, and it is only recently when use has become ubiquitous that concern for aspiration has also become widespread [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Of note, concern shared by the community regarding GLP-1 RAs has not been the same for many other commonly administered medications associated with decreased gastric emptying, including opioids, cardiovascular medications (beta and calcium channel blockers), anticholinergics, antacids, and neurological and psychiatric medications.

4.1. Variable Association of GLP-1 RAs with Retained Gastric Contents

There were conflicting reports of retained gastric contents in the higher-quality-of-evidence retrospective and prospective studies reviewed. For the retrospective studies, five of six studies investigated an association of GLP-1 RAs with retained gastric contents. Of these five studies, three studies (Wu et al., Kobori et al., and Silveira et al. [39,40,42]) showed a positive association while the remainder did not (two studies by Stark et al. and Bi et al. [38,39,40,41]). For the prospective studies, only three of the four studies investigated retained gastric contents. All three of these studies showed significant increase in gastric residue rates on either capsule endoscopy after starting GLP-RAs (in the case of the study by Nakatani et al. [33]) or on gastric ultrasound in the GLP-1 user group compared to non-user groups (in the cases of the studies by Sherwin et al. and Sen et al. [35,36]); of note, all three studies reported significant residue rates in the non-GLP-1 RA user groups as high as 32.1 ± 24% and 32.1 ± 35.3% in the diabetic neuropathy and non-diabetic neuropathy groups, respectively, reported in the study by Nakatani et al. [33]. Furthermore, retained gastric contents were found in up to 20% of the non-GLP-1 RA user group assessed by ultrasound in the study by Sherwin et al. and in 19% of the non-GLP-1 RA user group assessed by gastric ultrasound in the Sen et al. study [35,36]. Thus, the high gastric residue rates found in the groups of patients not taking GLP-1 RAs must be considered as a significant confounding factor in the noncontrolled case reports and series reporting increased gastric food contents and increased gastric residuals; the medical conditions and medications associated with delayed gastric emptying in many of these studies also serve as significant confounding factors. It is also important to note that only the study by Bi et al. excluded patients with diabetes in their analysis of GLP-1 RA and retained gastric contents [38]. This study did not identify a statistically significant association between GLP-1 and retained gastric food during upper endoscopy in their multivariate analysis, while opioids, antacids, and cardiovascular medications were associated with retained gastric contents.

4.2. Variable Association of GLP-1 RAs with Aspiration and Regurgitant Events

The literature reflects significant variability regarding the association of GLP-1 RAs with regurgitant events and aspiration on review of the higher-quality retrospective and prospective studies. For the retrospective studies, three of the six studies assessed aspiration events. Among these, the study by Anazco et al. revealed a similar aspiration rate of 4.8 cases per 10,000 endoscopies in patients taking GLP-1 RA compared with the 4.6 cases per 10,000 endoscopies previously reported in a prior Mayo Clinic study [37]. In this study, Anazco et al. used a previously validated automatic search algorithm of the electronic medical record system and reported two aspiration events in patients after receiving GLP-1 RA prescription, both of whom had significant confounding factors for aspiration including diabetes (HbA1c 6.7%) in one patient and gastric reflux with diffuse gastric antral vascular ectasia and bleeding requiring APC in the other patient [37]. The remaining retrospective reviews by Wu et al. and Silveira et al. each had a report of a single aspiration event during endoscopy, with the patients who aspirated having significant risk factors for aspiration [40,41,42]. All the patients on GLP-1 RA who aspirated in the retrospective studies survived, with two of the four patients requiring ICU admission (1 and 3 days total), one patient requiring non-ICU hospitalization and one patient being discharged on oxygen.

Only one (Quasi et al. [34]) of the four prospective studies studied regurgitant events evaluated by reflux episode frequency using esophageal pH and manometry. In this study, there was no significant difference for reflux episode frequency between GLP-1 RA users and non-users despite a significant prolonged gastric emptying time on the octanoate acid breath test, suggesting that their risk for reflux or regurgitation associated aspiration events may not be increased with GLP-1 RA use [34]. This is important because reflux is a significant risk factor for aspiration and regurgitant events and an important factor anesthesia providers use to determine the need for rapid sequence induction; however, it is important to note that a regurgitant event does not necessarily lead to a significant aspiration event [11]. It is also important to note that the case reports and case series reporting aspiration and/or regurgitant events reported patients that had confounding medical, surgical, anesthesia-related, procedural, and medication-related factors associated with delayed gastric emptying, increased secretions, and post-operative nausea and vomiting. None of the patients in the case reports and series reported any long-term negative sequelae of the aspiration or regurgitant events. All patients that suffered aspiration or regurgitant events were discharged by the following day with the exception of one patient (in the case series by Avraham et al. [43]), who was discharged from the hospital after a week.

Interestingly, we queried the clinicaltrial.gov database for all completed and terminated studies that involved GLP-1 RAs reported in our study (liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide, and exenatide) and had reported study results, which revealed a total of 399 studies (372 completed and 27 terminated), of which 12 of the completed studies and none of the terminated studies specifically mentioned aspiration, aspiration pneumonitis, aspiration pneumonia, and foreign body aspiration as an adverse event in their study results; of these 12 studies, 9 of the studies had a control drug or placebo group to compare with the GLP-1 RA group’s incidence of reported adverse events. Our query revealed one study with equal incidence of reported aspiration pneumonia in both the GLP-1 RA and placebo groups (clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT01147250); six studies had higher rates of aspiration and/or aspiration pneumonia in GLP-1 RA group compared to placebo/control (clinicaltrials.gov IDs NCT04184622, NCT03574597, NCT01720446, NCT01144338, NCT02692716, and NCT01621178); and two studies had higher incidences of reported aspiration and/or foreign body aspiration in the placebo group compared to the GLP-1 RA group. (clinicaltrails.gov IDs NCT01179048 and NCT01394952). We also queried the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), which revealed that the GLP-1 RAs reported in our study (liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide, and exenatide) reported aspiration, aspiration pneumonitis, and aspiration pneumonia in a total of 146 cases out of 252,418 total adverse event cases reported (0.058%), which was less than that for other medication typically continued in the perioperative period, particularly aspirin, simvastatin, atorvastatin, metoprolol, and carvedilol, which reported aspiration, aspiration pneumonitis, and aspiration pneumonia in a total of 205 cases out of 258,429 total adverse event cases reported (0.079%). It is important to note that the reported data from FAERS does not reflect actual incidence rates, and may be subject to underreporting and reporting bias. Nevertheless, the low number of aspiration-related cases reported in both groups and the results from our scoping review suggests that the risk may be lower than initially perceived and possibly overstated. Further studies are necessary to determine the risk for aspiration and/or regurgitant events relative to other medications and medical/surgical conditions associated with delayed gastric emptying.

4.3. Potential Impact of Diabetes and the Severity of Disease

From the larger prospective studies by Nakatani et al., Sherwin et al., and Sen al., it is evident that the gastric residual contents are relatively high even in the non-GLP-1 receptor agonist analysis groups [33,35,36]. These studies did not exclude diabetics in the user and non-user groups, which is informative because the study populations are representative of the real world patient populations often using GLP-1 receptor agonists and undergoing anesthetic procedures. Only the retrospective study by Bi et al. excluded diabetics as part of their GLP-1 receptor agonist and gastric residue analysis, finding no significant association with GLP-1 receptor agonists with retained gastric food during upper endoscopy on multivariate analysis [38]. However, the small number of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists in the study may have been a limiting factor in the ability to detect a difference. In the same study by Bi et al., the authors reported that opioids, antacids, and cardiovascular medications were associated with retained gastric food [38]. It is noteworthy to compare the findings from these studies with the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZA) guidance indicating that discontinuing GLP-1 receptor agonists does not alter the risk of delayed gastric emptying that is inherently associated with diabetes [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

It is possible that diabetes severity may play a role in the differential response to GLP-1 RA intake and overall risk profile. The prospective study by Nakatani et al. found that, using capsule endoscopy, the gastric, duodenal, and small intestine transit times were significantly increased after liraglutide administration compared to before starting liraglutide in diabetic patients with non-diabetic neuropathy but not in patients with diabetic neuropathy despite showing a significantly increased gastric residue in both nondiabetic neuropathy and diabetic neuropathy diabetic patients [33]. This may reflect increased gastrointestinal side effects in patients without severe diabetes who have not developed gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy and are taking GLP-1. It is unclear whether this leads to a clinically significant increase in gastric residuals that may place the patient at risk for aspiration. In the Silveira et al. study, the authors found that the perioperative use of GLP-1 RAs was associated with increased residual gastric content, which they defined as any amount of solid content or >0.8 mL/Kg measured from aspiration or suction canister compared to non-users (24.2% vs. 5.1%, p < 0.001), but not the subjective amount of residual gastric content found on EGD by visual estimation (small, medium, large) [40]. For a 70 kg person, this threshold for residual gastric content would equate to just 56 mL measured from aspiration or suctioned from the canister. This is well below the 500 mL threshold used in critical care settings, where gastric residuals above this amount raise concerns for ileus and often result in the discontinuation of tube feeds [59]. While many of the case reports did report high gastric residuals of greater than 500 mL when assessed with nasogastric or orogastric tube, many of the patients had diabetes and/or did not specifically mention the presence or absence of the patient’s other medical history that may serve as potential confounding factor. The study by Gulak et al. was the only case report or case series where the patient was noted not to be diabetic, specifically mentioned the patient’s other medical issues, and reported regurgitation or gastric residual volumes [52]. In this report, the patient exhibited regurgitation of 200 mL of clear fluid during induction of anesthesia, with minimal gastric content observed after orogastric tube placement. Additionally, the patient has a history of hypothyroidism, which may contribute as a confounding factor for high residual volumes. The remaining case reports and series by Rai et al., Ishihara et al., and Weber et al. evaluated gastric residuals through orogastric or nasogastric tube placement. Both Rai et al. and Ishihara et al. included patients with diabetes, while the patient in the correspondence from Weber et al. did not have diabetes. However, Weber et al. did not provide specific details about the patient’s other medical history, which could also have acted as confounding factors [53,55,56]. Higher-quality retrospective and prospective studies are needed to clarify the risk of clinically significant increases in gastric residuals associated with GLP-1 RAs.

Importantly, withholding GLP-1 RAs in the perioperative period may lead to significant elevations in blood glucose, particularly in patients using GLP-1 RAs for hyperglycemia management. Elevated blood glucose levels are associated with increased perioperative morbidity and mortality and include complications such as impaired wound healing and increased surgical site infection [60,61,62]. Thus, careful consideration of both glycemic control and aspiration risk is critical, and future guidelines should consider balancing these competing risks, providing evidence-based recommendations that prioritize patient safety and optimal surgical outcomes.

4.4. Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Risk for Retained Gastric Contents

The impact of gastrointestinal symptoms on retained gastric contents was evaluated in one retrospective study, four case series, and five case reports. In the retrospective study of patients undergoing upper endoscopies by Silveira et al., propensity weighted analysis revealed a significant increased risk for residual gastric contents when patients had preoperative digestive symptoms (including nausea/vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal distension) both in semaglutide users and non-users [40]. There was one reported case (0.24%) of pulmonary aspiration under deep sedation in the GLP-1 RA group; however, it was not reported if this patient had gastrointestinal symptoms prior to his procedure and it was noted that he had confounding factors including history of gastric bypass. Thus, this study by Silveira et al. suggests that pre-endoscopy digestive symptoms may be helpful in identifying higher risk patients, particularly those using GLP-1 RAs. Interestingly, patients undergoing both EGD and colonoscopy showed a protective effect against residual gastric content, possibly secondary to the prolonged (for as long as a day or two prior to the procedures) clear liquid colon preparations prescribed for patients undergoing colonoscopies [40]. This has caused some institutions, including the authors’ own institution, to recommend consideration of a clear liquid diet for 24 h prior to scheduled arrival to the hospital for all patients prescribed GLP-1 RAs. In the four case series and five case reports where gastrointestinal symptoms were evaluated, there was not a consistent relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms and gastric residuals or regurgitant and aspiration events, as detailed in Supplementary Text S2. The case series and report studies where gastrointestinal symptoms were evaluated had patients with confounding factors for increased gastric content, residual food content, and aspiration.

Many major organizations, including the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), recognize that gastrointestinal symptoms can significantly influence anesthesia management. This can lead to the cancellation or postponement of procedures, the withholding of certain medications, the use of gastric ultrasound for additional evaluation, and decisions regarding the type and induction of anesthesia [14,22,23]. More prospective and retrospective studies are needed to clarify the role of gastrointestinal symptoms, both in general and specifically in patients receiving GLP-1 RAs, in relation to the risk of retained gastric contents.

4.5. Holding of Medications Prior to Procedure

There is significant variation in the guidelines and recommendations from major societies regarding the withholding of GLP-1 RAs before a procedure. For example, the ASA advises that patients should pause weekly injections of GLP-1 RAs for one week prior to the procedure and refrain from taking daily oral doses on the day of the procedure. In contrast, several other organizations, including the Association of Anesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGB) and Centre for Perioperative Care (CPOC), recommend that patients do not need to hold GLP-1 RAs before the procedure [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,23,24]. The AGA recommends an individualized approach regarding the withholding of doses before endoscopy for patients taking GLP-1 RAs solely for weight loss [22]. While this practice may carry little risk, there is uncertainty about its effectiveness in restoring normal gastric motility, so it should not be considered mandatory or evidence based. For patients using GLP-1 RAs for diabetes management, the AGA notes a lack of compelling evidence to support withholding doses, emphasizing that maintaining proper glycemic control is essential before undergoing sedation, anesthesia, and endoscopy procedures [22]. It is important to note that the half-life these medications varies, from daily for daily oral dosing medications to weekly for weekly injection dosing, leading some to suggest that they should be withheld for at least three half-lives to fully allow the medications to clear. There are no prospective studies examining the impact of withholding GLP1 RAs for a set period of time prior to their procedures. Two of the four prospective studies included in our review specifically mentioned when the GLP-1 RA was last taken. The study by Nakatani et al., which specifically mentioned that the GLP-1 RA liraglutide was taken on the day of the capsule endoscopy, and the Sen et al. study, which mentioned that the majority of all 62 patients taking GLP-1 RAs, with the exception of 7 patients, had taken their GLP-1 RAs semaglutide, dulaglutide, or tirzepatide in the last 7 days, with the remaining 7 patients having withheld their GLP-1 RA for 8–15 days [33,34,35]. In the Sen et al. study, there was no significant association between the duration of withholding GLP-1 RA and prevalence of retained gastric contents [35]. In the Nakatani et al. study, there was no significant difference in the gastric, duodenal, and small intestine transit time after GLP-1 RA use compared to before starting GLP-1 RAs in diabetic patients with neuropathy; however, the gastrointestinal transit time was significantly increased after GLP-1 RA administration compared to before starting the GLP1 analogue liraglutide in diabetic patients without neuropathy [33]. The gastric residue rate was significantly higher following the use of GLP-1 RA compared to baseline in diabetics with and without neuropathy. This suggests that holding GLP-1 RAs in diabetics is likely to reduce the risk for gastric residues in diabetic patients with and without neuropathy but is unlikely to affect gastrointestinal transit times in patients with significant diabetic neuropathy. This is consistent with the guidance provided by major societies such as the ASA, AANA, ISMP, and Columbian Society of Anesthesiology and Reanimation (SCARE), which recommend that GLP-1 RAs be held irrespective of the indication of use [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,28,29,30]. The results by Nakatani et al. may be contrary to guidance provided by major societies such as the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA), who state that holding GLP-1 RAs does not alter the risk of delayed gastric emptying that is inherently associated with diabetes [14,15,16]. Only one of the six retrospective studies included in our review specifically examined the impact of the timing of when the last GLP-1 RA administration was last taken, which was the study by Silveira et al., which reported a mean GLP-1 RA interruption time of 10 days prior to endoscopy, with patients being instructed to hold the GLP-1 RA for 10–14 days prior, but some were unable to follow the instructions for a variety reasons (i.e., last minute notice to fill case cancelation) [40]. They reported GLP-1 RA users had a significant increase in the residual gastric content (defined in their study as any amount of solid content or >0.8 mL/Kg measured from aspiration/suction canister) compared to non-users, but not the subjective amount of residual gastric content found on EGD by visual estimation (small, medium, large). This may suggest that holding the drug for 10–14 days may not be clinically sufficient if the goal is to reduce the residual gastric content to minimize risk for aspiration; however, as mentioned above, it is unclear whether an amount of 0.8 mL/kg is considered clinically significant particularly when the residual gastric content could not be subjectively visually assessed. Despite the qualitative increase in residual gastric content for GLP-1 RA users, there was only one reported case of pulmonary aspiration (0.24%) in the Silveira et al. study, and the patient had last taken his semaglutide 11 days prior and had a prior history of gastric bypass, a significant confounding factor for aspirations [40]. Thus, withholding the drug for 10–14 days appears to result in minimal risk for aspiration despite increased residual gastric content; there are no prospective or retrospective studies assessing patients who have held the drug for just a week, or even 3–4 weeks as others have suggested. Of the case reports and series, only two studies, by Wilson et al. and Raven et al., had patients where the GLP-1 RAs were held according to the ASA guidelines of at least a week for weekly injectables and on the day of surgery for daily oral GLP-1 RAs [14,46,47]. In the case series by Wilson et al., one of the two patients held their oral semaglutide on the morning of surgery and had multiple episodes of bile-tinted projectile vomiting post-extubation [47]. The confounding factor for this regurgitant event was the type of surgery (thyroidectomy), which is often associated with significant post-operative nausea and vomiting. In the other study, by Raven et al., one of the patients in the case series had an initial upper endoscopy which revealed a stomach full of solid food when the patient did not hold his semaglutide; follow-up upper endoscopy after withholding the patient’s GLP-1 RA for 3 weeks revealed an empty stomach [46]. Of note, this patient had multiple confounding factors, including a history of esophagitis on PPI and hypothyroidism on thyroxine at stable doses. From the studies included in our review, there is limited evidence to guide the optimal duration that the GLP-1 receptor should be held prior to procedures.

Interestingly, while several US-based medical societies recommend withholding GLP-1 RAs in the perioperative period, most international guidelines do not advocate for this practice. This discrepancy likely reflects a more precautionary approach in the US, possibly driven by concerns about medico-legal liability, despite the limited evidence supporting a significant risk of aspiration. As more robust data emerge, there is a need to reevaluate these recommendations and develop a global consensus grounded in high-quality scientific evidence.

4.6. Prolonged Fasting to Reduce Retained Gastric Food and Residuals

Increased fasting times for solids and liquids are often used as a strategy to reduce gastric contents and aspiration in patients at increased risk. Currently, the majority of the major societies providing perioperative guidance, including the ASA, Institute for Safe Medication Practices in Canada (ISMP), and American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA), do not make recommendations for increasing the duration of fasting in patients taking GLP-1 RAs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,28,29]. The CAS is the only society that recommends a prolonged fasting period as a strategy to minimize the risk of aspiration; however, they do not specify the duration of fasting [19]. All of the studies in this review which reported an association with gastric residual content, high gastric residuals, aspiration, and/or regurgitant events reported fasting times exceeded standard ASA guidelines, as prolonged as 20 h for solids and 18 h for liquids in some studies. This also included the retrospective and prospective studies that had reported fasting times of at least 10 h and median of 14.5 h for solids and clear liquids of 9.3 h. Notably, in the study by Silveira et al. in which patients underwent both upper and lower endoscopies, prolonged fasting appeared to have a protective effect against residual gastric content [40]. Patients undergoing colonoscopies fast for 48 h with solids and 24 h for liquids. A prolonged fast of this magnitude may be associated with a reduced risk for residual gastric contents and aspiration/regurgitant events. Further studies are necessary to determine if and the duration of prolonged fasting reduces retained gastric food contents and residuals, and whether this is procedure-dependent.

4.7. Gastric Ultrasound Studies to Assess Aspiration Risk

Gastric ultrasound is a noninvasive tool that can be used to assess aspiration risk and guide clinical management. The CAS, ASA, ANZCA, and AGA all recognize gastric ultrasound as a potentially helpful tool to assess risk and guide perioperative management of patients on GLP-1 RAs [16,17,18,19,22,23]. Only four studies involved gastric ultrasound to assess patients with GLP-1 RAs. These studies included the two prospective studies by Sherwin et al. and Sen et al., the case series by Kittner et al., and the case report by Giron Arango et al. [35,36,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The prospective study by Sherwin et al. involved assessment for solid gastric contents using gastric ultrasound [36]. The study found that, after an 8 h fast, 70% of participants in the GLP-1 RA group displayed solid gastric contents when assessed in the supine position, while 90% showed solid contents in the lateral position. In comparison, only 10% and 20% of participants who did not use GLP-1 RAs showed solid gastric contents in the supine and lateral positions, respectively. Subsequently, participants underwent a gastric ultrasound study two hours after consuming clear liquids. The results showed no difference in gastric content in the lateral position; however, a significant difference was observed in the supine position, where 90% of the control group had empty stomachs compared to only 30% of the GLP-1 RA group. Of note, patients with medical conditions associated with delayed gastric emptying were not excluded; participants were noted to have a history of diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyloidosis, and scleroderma, all of which are associated with delayed gastric emptying. The authors also noted in their study that they have data from non-orthopedic patients who underwent gastric ultrasound during the same period at their institution and revealed seven out of eight patients on GLP-1 RAs with adequate fasting periods had retained solid food. The prospective study by Sen et al. reported higher retained gastric contents in the GLP-1 RA group compared to the non-user group (56% versus 19%) evaluated by preprocedural gastric ultrasound; of note, the patients had confounding factors, including diabetes, GERD, home opioid use, and high ASA physical status classification [35]. The case series by Kittner et al. reported retained solids in all three patients who had fasted 10–14 h and were assessed preoperatively for orthopedic procedures who had fasted 10–14 h, resulting in case postponements; of note, all three patients had type 2 diabetes [45]. The case report by Giron-Arango et al. revealed increased gastric volume assessed by gastric ultrasound consistent with a full stomach; this patient also had type 2 diabetes, which may have been a confounding factor [51]. Further studies are necessary to determine the utility of gastric ultrasound in improving clinical outcomes.

4.8. Type, Dosing, and Duration of GLP-1 RA Use

There is significant concern in the literature that differences in the type, dosing, and duration of action of individual GLP-1 RAs may be important variables impacting gastric emptying, regurgitation, and aspiration risk. Specifically, higher doses of medications may result in a significant slowing of gastric emptying compared to lower dosing of medications using indirect measurements of gastric emptying, and that the duration of GLP-1 RA use may play a role given studies suggesting tachyphylaxis after prolonged GLP-1 RA use [63,64,65,66]. None of the major societies provide guidance based on the type, dosing, and duration of GLP-1 RA aside from the duration of time that individual GLP-1 RA drugs should be held based on their duration of action [14]. From the studies included in this review, there is insufficient evidence to indicate a clear association between the type, dose, and duration of GLP-1 RA use and gastric food content, increased gastric residuals, aspiration, and/or regurgitant events. The study by Kobori et al. found that gastric residue occurrence was highest with semaglutide 1.0 mg oral dosing; of note, patients in the study took semaglutide injection doses ranging from 0.25 to 1.0 mg [39]. The study also found no gastric residue in patients treated with doses of liraglutide (≤1.5 mg), lower doses of semaglutide (0.25 mg), and any dose of oral semaglutide, lixisenatide, or exenatide. In contrast, many of the other studies showed incidences of gastric food content, increased gastric residuals, aspiration, and/or regurgitant events with these formulations and dosing. The studies included in this review had varying reports of GLP-1 RA use duration. Gastric food content increased gastric residuals, aspiration, and/or regurgitant events occurring during both shorter- and longer-term use of GLP-1 RA in the studies reviewed. In their retrospective study, Silveira et al. report that the duration of preoperative semaglutide cessation did not impact the presence or absence of residual gastric contents [40].

Nevertheless, the ASA, AANA, and ISMP provide specific guidance on the duration of withholding GLP-1 RAs beyond just the day of surgery [23,28,29]. Both the ASA and AANA suggest that for weekly dosing of GLP-1 RAs, consideration is to be given to withholding the medication a week before surgery; for GLP-1 RAs that are taken daily, consideration should be given to withholding on the day of surgery [23,24,25,26,27,28]. The ISMP suggests that consideration be given to withholding GLP-1 RAs for at least three half-lives before the procedure [29]. The ASA advises that GLP-1 RAs be withheld before surgery/procedures, regardless of the indication, dose, or type of procedure [23]. The ASA also notes that the effects on gastric emptying decrease with long-term use, likely due to tachyphylaxis from vagal nerve activation, but does not provide any details related to specific adjustments in management regarding the duration of GLP-1 RA use [23].

4.9. Limitations

There are limitations with our scoping review of the literature. Many of the studies included in our review are of low-quality evidence, including the case reports and series. The higher-quality studies, both retrospective and prospective, were often limited by small sample sizes, single institutions, and lack of blinding. Many of the studies included incomplete or the absence of details related to GLP-1 RA use (i.e., specific type, dosage, frequency, duration, timing of discontinuation), patient medical and surgical history, other potential confounding factors, and other notable findings (i.e., gastrointestinal symptoms, elevated gastric residual volume, residual gastric food contents) related to GLP-1 RA use. Finally, our review included only studies published in English and did not examine those found in the gray literature, such as technical reports and conference proceedings.

5. Conclusions