Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with a Religious Focus: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Survey Instrument

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

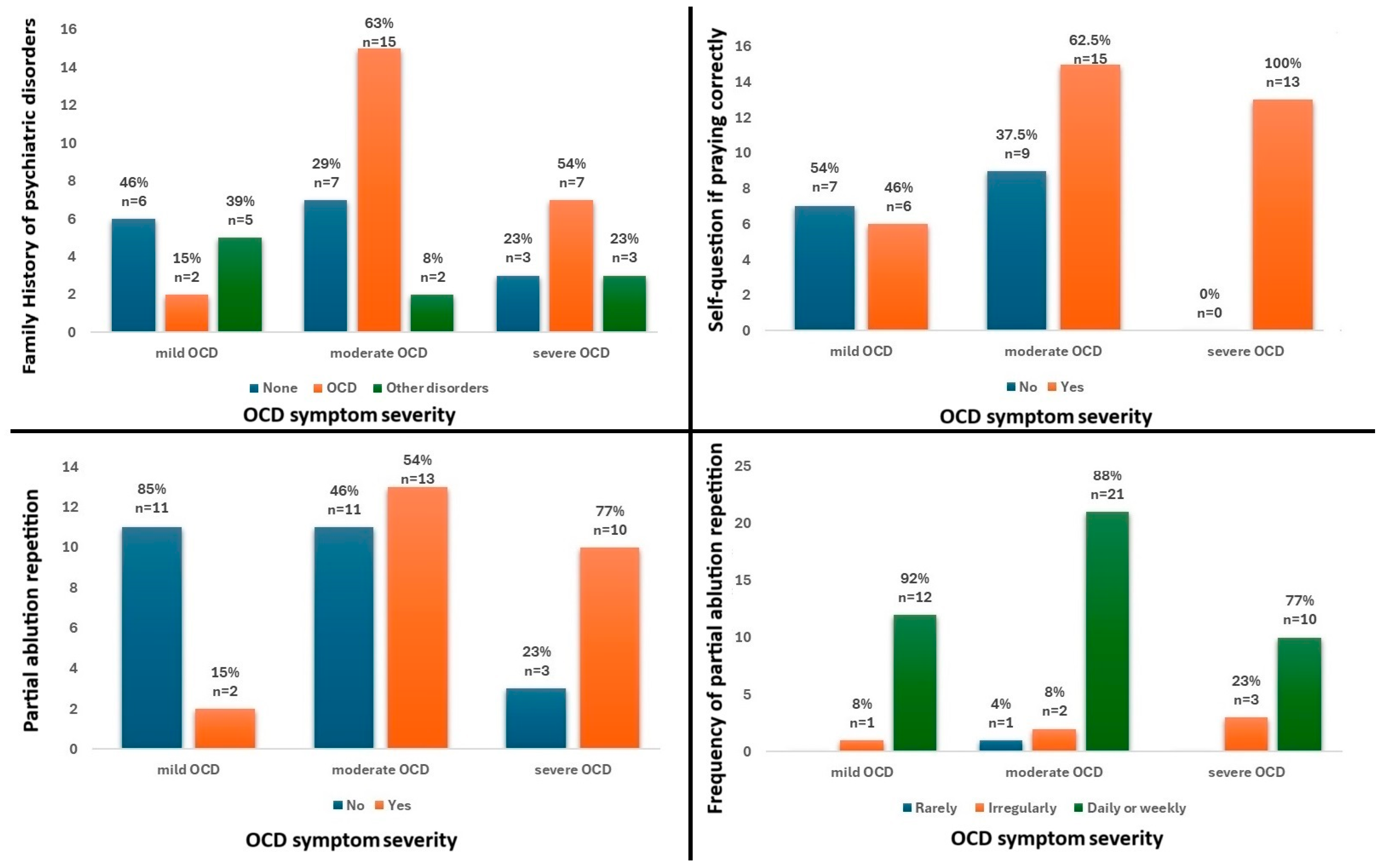

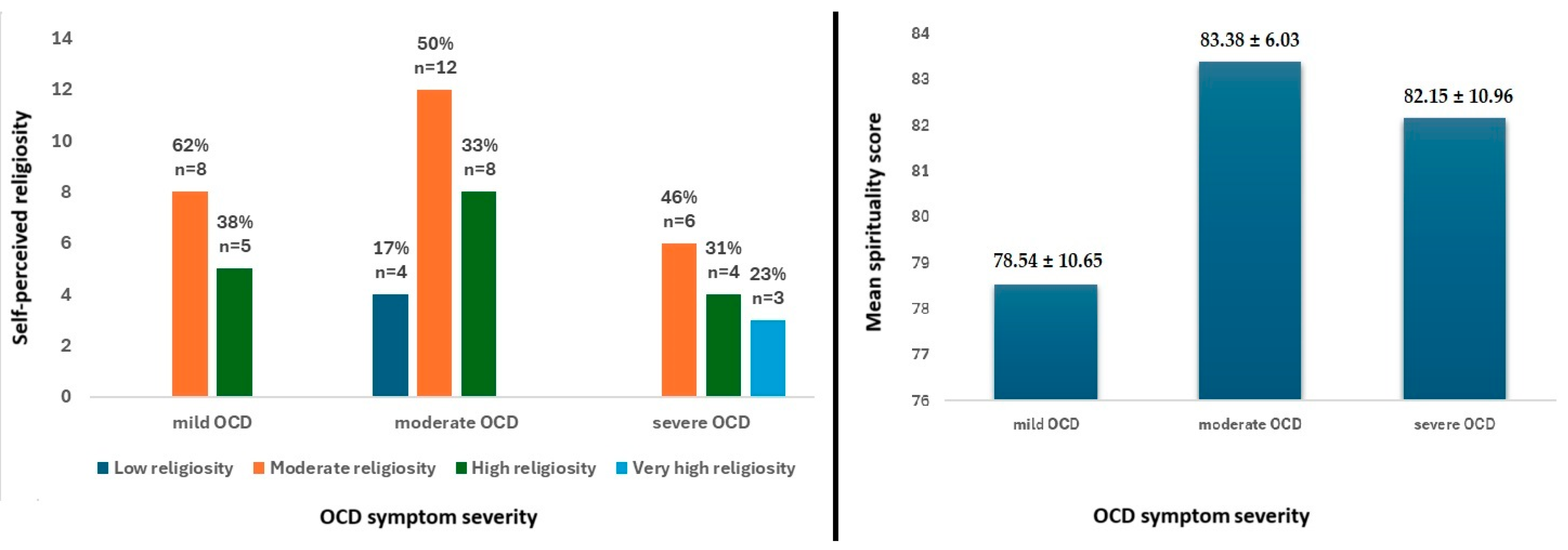

3.2. Bivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

4.2. Religiosity and Spirituality

4.3. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirschtritt, M.E.; Bloch, M.H.; Mathews, C.A. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 2017, 317, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chalah, M.A.; Ayache, S.S. Could Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Join the Therapeutic Armamentarium in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, D.J.; Costa, D.L.C.; Lochner, C.; Miguel, E.C.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Shavitt, R.G.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; Simpson, H.B. Obsessive–Compulsive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, H.; Hany, M. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorsders, 5th ed.; text rev; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, E.G.; Mneimneh, Z.N.; Karam, A.N.; Fayyad, J.A.; Nasser, S.C.; Chatterji, S.; Kessler, R.C. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in Lebanon: A national epidemiological survey. Lancet 2006, 367, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani, Z.; Rahimi, C.; Mohammadi, N. Birth Order and Sibling Gender Ratio of a Clinical Sample Predicting Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Subtypes Using Cognitive Factors. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2016, 11, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palermo, S.; Marazziti, D.; Baroni, S.; Barberi, F.M.; Mucci, F. The Relationships Between Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Psychosis: An Unresolved Issue. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, A.L.; Kvale, G.; Hansen, B.; van den Heuvel, O.A. Symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder as predictors of neurobiology and treatment response. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2018, 5, 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, B.P.; Wang, D.; Li, M.; Perriello, C.; Ren, J.; Elias, J.A.; Van Kirk, N.P.; Krompinger, J.W.; Pope, H.G.; Haber, S.N.; et al. Use of an Individual-Level Approach to Identify Cortical Connectivity Biomarkers in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2019, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Martiadis, V.; Pessina, E.; Martini, A.; Raffone, F.; Besana, F.; Olivola, M.; Cattaneo, C.I. Brexpiprazole Augmentation in Treatment Resistant OCD: Safety and Efficacy in an Italian Sample. Psychiatr. Danub. 2024, 36 (Suppl. S2), 396–401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martiadis, V.; Pessina, E.; Martini, A.; Raffone, F.; Cattaneo, C.I.; De Berardis, D.; Pampaloni, I. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors augmentation with cariprazine in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: A retrospective observational study. CNS Spectr. 2024, 1–4, epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Deacon, B.J.; Woods, C.M.; Tolin, D.F. Association between Protestant re-ligiosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms and cognitions. Depress. Anxiety 2004, 20, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, T.B.; Özçelik, H.N. Psychotherapies for the treatment of scrupulosity: A systematic review. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 22361–22375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Huppert, J.D.; Cohen, A.B.; Tolin, D.F.; Cahill, S.P. Religious obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample: The Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS). Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, B.O.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Williams, N.L.; Connolly, K.M.; Lohr, J.M. Scrupulosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Confirmatory factor analysis and validity of the Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.A.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Whiteside, S.P.; Deacon, B.J. Scrupulosity in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: Relationship to clinical and cognitive phenomena. J. Anxiety Disord. 2006, 20, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.L.; Abramowitz, J.S. The cognitive mediation of thought-control strategies. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 1949–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Whiteside, S.; Kalsy, S.A.; Tolin, D.F. Thought control strategies in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A replication and extension. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, J.L.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Riemann, B.C.; Reuman, L.; Blakey, S.M.; Leonard, R.C.; Thompson, K.A. Scrupulosity, Religious Affiliation and Symptom Presentation in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2019, 47, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himle, J.A.; Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Nguyen, A. The relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder and religious faith: Clinical characteristics and implications for treatment. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2011, 3, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.; Huppert, J.D. Scrupulosity: A unique subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2010, 12, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolini, H.; Salin-Pascual, R.; Cabrera, B.; Lanzagorta, N. Influence of Culture in Obsessive-compulsive Disorder and Its Treatment. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2017, 13, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siev, J.; Baer, L.; Minichiello, W.E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with predominantly scrupulous symptoms: Clinical and religious characteristics. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siev, J.; Rasmussen, J.; Sullivan, A.D.W.; Wilhelm, S. Clinical features of scrupulosity: Associated symptoms and comorbidity. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siev, J.; Steketee, G.; Fama, J.M.; Wilhelm, S. Cognitive and Clinical Characteristics of Sexual and Religious Obsessions. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2011, 25, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, D.F.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Kozak, M.J.; Foa, E.B. Fixity of belief, perceptual aberration, and magical ideation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2001, 15, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besiroglu, L.; Karaca, S.; Keskin, I. Scrupulosity and obsessive compulsive disorder: The cognitive perspective in Islamic sources. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorulmaz, O.; Gençöz, T.; Woody, S. OCD cognitions and symptoms in different religious contexts. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinker, M.; Jaworowski, S.; Mergui, J. Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in the ultra-orthodox community—Cultural aspects of diagnosis and treatment. Harefuah 2014, 153, 463–466, 498, 497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoubila, A.; Kadri, N. Religious obsessions and religiosity. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Badaan, V.; Richa, R.; Jost, J.T. Ideological justification of the sectarian political system in Lebanon. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytiyeh, H. Has the Educational System in Lebanon Contributed to the Growing Sectarian Divisions? Educ. Urban Soc. 2017, 49, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. The development and validation of the Arabic Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Eur. J. Psychol Assess. 1998, 14, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Manual of the Arabic Scale of Obsession-Compulsion; The Anglo-Egyptian Bookshop: Cairo, Egypt, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. The construction and validation of the revised Arabic Scale of Obsession-Compulsion (ASOC). Online J. Neurol. Brain Disord. 2018, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally Elsayed, M.; Ahmed Ghazi, G. Fear of COVID-19 pandemic, obsessive-compulsive traits and sleep quality among first academic year nursing students, Alexandria University, Egypt. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, R.L.; Burg, M.A.; Naberhaus, D.S.; Hellmich, L.K. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale. Development and testing of a new instrument. J Fam Pract. 1998, 46, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musa, A.S. Psychometric Evaluation of an Arabic Version of the Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale in Jordanian Muslim College Nursing Students. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The Need to Report Effect Size Estimates Revisited. Trends Sport Sci. 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, B.M.; Morabito, D.M.; Schmidt, N.B. Epidemiological and Clinical Gender Differences in OCD. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benatti, B.; Girone, N.; Celebre, L.; Vismara, M.; Hollander, E.; Fineberg, N.A.; Stein, D.J.; Nicolini, H.; Lanzagorta, N.; Marazziti, D.; et al. The role of gender in a large international OCD sample: A Report from the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) Network. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 116, 152315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, M.A.; Alvarenga, P.D.; Funaro, G.; Torresan, R.C.; Moraes, I.; Torres, A.R.; Torres, A.R.; Zilberman, M.L.; Hounie, A.G. Gender differences in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A literature review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassan, W.; El Hayek, S.; de Filippis, R.; Eid, M.; Hassan, S.; Shalbafan, M. Variations in obsessive compulsive disorder symptomatology across cultural dimensions. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1329748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balachander, S.; Meier, S.; Matthiesen, M.; Ali, F.; Kannampuzha, A.J.; Bhattacharya, M.; Nadella, R.K.; Sreeraj, V.S.; Ithal, D.; Holla, B.; et al. Are There Familial Patterns of Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 651196. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.H.; Cheng, C.M.; Tsai, S.J.; Bai, Y.M.; Li, C.T.; Lin, W.C.; Su, T.-P.; Chen, T.-J.; Chen, M.-H. Familial coaggregation of major psychiatric disorders among first-degree relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A nationwide study. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 680–687. [Google Scholar]

- Cromer, K.R.; Schmidt, N.B.; Murphy, D.L. An investigation of traumatic life events and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosso, G.; Albert, U.; Asinari, G.F.; Bogetto, F.; Maina, G. Stressful life events and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Clinical features and symptom dimensions. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 197, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murayama, K.; Nakao, T.; Ohno, A.; Tsuruta, S.; Tomiyama, H.; Hasuzawa, S.; Mizobe, T.; Kato, K.; Kanba, S. Impacts of Stressful Life Events and Traumatic Experiences on Onset of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 561266. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.L.; Brock, R.L. The effect of trauma on the severity of obsessive-compulsive spectrum symptoms: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2017, 47, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mahgoub, O.M.; Abdel-Hafeiz, H.B. Pattern of obsessive-compulsive disorder in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1991, 158, 840–842. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Buchholz, J.L. Chapter 4—Spirituality/religion and obsessive–compulsive-related disorders. In Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rakesh, K.; Arvind, S.; Dutt, B.P.; Mamta, B.; Bhavneesh, S.; Kavita, M.; Navneet, K.; Shrutika, G.; Priyanka, B.; Arun, K.; et al. The Role of Religiosity and Guilt in Symptomatology and Outcome of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2021, 51, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inozu, M.; Ulukut, F.O.; Ergun, G.; Alcolado, G.M. The mediating role of disgust sensitivity and thought-action fusion between religiosity and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.D.; Lau, G.; Grisham, J.R. Thought-action fusion as a mediator of religiosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2013, 44, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassin, E.; Muris, P.; Schmidt, H.; Merckelbach, H. Relationships between thought-action fusion, thought suppression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A structural equation modeling approach. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000, 38, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.E.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siev, J.; Cohen, A.B. Is thought-action fusion related to religiosity? Differences between Christians and Jews. Behav Res Ther. 2007, 45, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siev, J.; Chambless, D.L.; Huppert, J.D. Moral thought-action fusion and OCD symptoms: The moderating role of religious affiliation. J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, N.C.; Stark, A.; Ramsey, K.; Cooperman, A.; Abramowitz, J.S. Prayer in Response to Negative Intrusive Thoughts: Closer Examination of a Religious Neutralizing Strategy. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2014, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J.; Siev, J.; Abramovitch, A.; Wilhelm, S. Scrupulosity and contamination OCD are not associated with deficits in response inhibition. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.J.; Berman, N.C.; Graziano, R.; Abramowitz, J.S. Examining Attentional Bias in Scrupulosity: Null Findings From the Dot Probe Paradigm. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 29, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, J.D.; Siev, J. Treating scrupulosity in religious individuals using cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2010, 17, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.H.; Hedges, D.W. Scrupulosity disorder: An overview and introductory analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, J.D.; Siev, J.; Kushner, E.S. When religion and obsessive-compulsive disorder collide: Treating scrupulosity in Ultra-Orthodox Jews. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mild (n = 13) | Moderate (n = 24) | Severe (n = 13) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.489 | |||

| 18–29 years | 5 | 13 | 8 | |

| 30–49 years | 7 | 11 | 5 | |

| ≥50 years | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sex | 0.162 | |||

| Females | 5 | 17 | 9 | |

| Males | 8 | 7 | 4 | |

| Educational level | 0.057 | |||

| Middle school | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| High school | 2 | 9 | 0 | |

| University degree | 10 | 14 | 12 | |

| Relationship status | 0.713 | |||

| Single | 6 | 13 | 4 | |

| Married | 6 | 10 | 8 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Area of living (childhood) | 0.897 | |||

| Outside the capital | 10 | 20 | 11 | |

| Within the capital | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Area of living (current) | >0.999 | |||

| Outside the capital | 10 | 19 | 11 | |

| Within the capital | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| Monthly living income (Lebanese pounds and equal rates in USD) <2 millions (~22 USD) Between 2 and 5 millions (~22–56 USD) Between 5 and 10 millions (56–112 USD) Between 10 and 20 millions (112–224 USD) >20 millions (>224 USD) | 0 3 4 2 4 | 3 14 2 3 2 | 2 6 1 2 2 | 0.240 |

| Attended school | 0.913 | |||

| Religious | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| Non-religious | 6 | 13 | 5 | |

| Both | 4 | 6 | 4 | |

| Parents’ relationship status | 0.65 | |||

| Married | 12 | 18 | 11 | |

| Divorced | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Traumatic life events | 0.662 | |||

| No | 7 | 9 | 5 | |

| Yes | 6 | 15 | 8 | |

| Age of diagnosis | 0.184 | |||

| Before 12 years | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 12–18 years | 0 | 8 | 1 | |

| 18–25 years | 6 | 9 | 7 | |

| >25 years | 5 | 6 | 4 | |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | 0.043 | |||

| None | 6 | 7 | 3 | |

| OCD | 2 | 15 | 7 | |

| Others | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Current OCD medications | 0.119 | |||

| Untreated | 7 | 10 | 10 | |

| Treated | 6 | 14 | 3 | |

| Current or past psychotherapy | 0.482 | |||

| None | 9 | 12 | 6 | |

| Past | 1 | 7 | 5 | |

| Current | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| Praying frequency | 0.702 | |||

| Rarely | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Irregularly | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Daily or weekly | 12 | 21 | 10 | |

| Self-question if praying correctly | 0.005 | |||

| No | 7 | 9 | 0 | |

| Yes | 6 | 15 | 13 | |

| Self-question if prayers are accepted by God | 0.111 | |||

| No | 4 | 10 | 1 | |

| Yes | 9 | 14 | 12 | |

| Frequency of prayers repetition if questioning | 0.162 | |||

| None | 9 | 14 | 5 | |

| Once | 1 | 2 | 5 | |

| Twice | 1 | 6 | 3 | |

| Three of more | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Praying location | 0.830 | |||

| No preference | 7 | 16 | 6 | |

| As long as the setting is available | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Home only | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Home and praying place | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Frequency of partial ablution | 0.404 | |||

| Daily 3–5/day | 12 | 18 | 12 | |

| More than 5/day | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| Partial ablution repetition | 0.006 | |||

| No | 11 | 11 | 3 | |

| Yes | 2 | 13 | 10 | |

| Frequency of partial ablution repetition | 0.041 | |||

| None | 11 | 11 | 3 | |

| Once | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Twice | 1 | 6 | 3 | |

| Three or more | 0 | 5 | 3 | |

| Partial ablution location | 0.058 | |||

| No preference | 6 | 15 | 4 | |

| Home only | 5 | 9 | 5 | |

| Home and praying place | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Full ablution repetition | 0.123 | |||

| No | 10 | 16 | 5 | |

| Yes | 3 | 8 | 8 | |

| Frequency of full ablution repetition | 0.166 | |||

| None | 10 | 16 | 5 | |

| Once | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| Twice | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Three of more | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Frequency of fasting practice | 0.252 | |||

| None | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| During the holy month | 10 | 11 | 6 | |

| 1–6 months per year | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Throughout the year during religious ceremony | 0 | 5 | 2 | |

| Self-question if fasting correctly | 0.282 | |||

| No | 10 | 16 | 6 | |

| Yes | 3 | 8 | 7 | |

| Self-question if fasting accepted by God | 0.703 | |||

| No | 9 | 15 | 7 | |

| Yes | 4 | 9 | 6 | |

| Frequency of fasting repetition | 0.495 | |||

| None | 10 | 21 | 9 | |

| Rarely | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Sometimes | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Frequency of suspecting intrusive thoughts related to ritual impurity | 0.365 | |||

| None | 6 | 6 | 2 | |

| Sometimes | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| >once per month | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| >once per week | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| >once per day | 3 | 12 | 9 | |

| Frequency of attempts to correct suspected ritual impurities | 0.445 | |||

| None | 6 | 6 | 2 | |

| Rarely | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Sometimes | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| Every time | 5 | 13 | 10 | |

| Blasphemous thoughts | 0.459 | |||

| No | 10 | 13 | 8 | |

| Yes | 3 | 11 | 5 | |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding the holy book | >0.999 | |||

| No | 11 | 19 | 11 | |

| Yes | 2 | 5 | 2 | |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding religious scripts or prophetic Hadiths | >0.999 | |||

| No | 8 | 16 | 9 | |

| Yes | 5 | 8 | 4 | |

| Perceived parents’ religiosity | 0.221 | |||

| No Practice | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Low | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| moderate | 7 | 11 | 5 | |

| High | 3 | 5 | 7 | |

| Very high | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Perceived self-religiosity | 0.104 | |||

| Low | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| moderate | 8 | 12 | 6 | |

| High | 5 | 8 | 4 | |

| Very high | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Frequency of visiting religious places/centers | 0.864 | |||

| None | 2 | 6 | 1 | |

| Rarely | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Religious occasions | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 2 | 6 | 2 | |

| Weekly | 3 | 7 | 4 | |

| Daily | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| SIBS scores | 78.54 ± 10.65 | 83.38 ± 6.03 | 82.15 ± 10.96 | 0.277 |

| Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis Test Statistics | p Value | Effect Size (r or E2R) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | H = 3.044 | 0.218 | 0.062 |

| Sex | U = 232.000 | 0.211 | 0.177 |

| Educational level | H = 2.845 | 0.416 | 0.008 |

| Relationship status | H = 0.248 | 0.884 | 0.005 |

| Area of living (childhood) | U = 180.500 | 0.921 | 0.014 |

| Area of living (current) | U = 193.000 | 0.877 | 0.024 |

| Monthly living income (Lebanese pounds) | H = 4.266 | 0.371 | 0.087 |

| Attended school | H = 0.915 | 0.633 | 0.019 |

| Parents’ relationship status | H = 0.120 | 0.942 | 0.002 |

| Traumatic life events | U = 365.500 | 0.230 | 0.170 |

| Age of diagnosis | H = 0.611 | 0.894 | 0.012 |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | H = 4.419 | 0.110 | 0.090 |

| Current OCD medications | U = 248.00 | 0.223 | 0.172 |

| Current or past psychotherapy | H = 1.665 | 0.435 | 0.034 |

| Praying frequency | H = 1.386 | 0.500 | 0.028 |

| Self-question if praying correctly | U = 390.000 | 0.014 | 0.347 |

| Self-question if prayers are accepted by God | U = 300.000 | 0.427 | 0.112 |

| Frequency of prayers repetition if questioning | H = 3.552 | 0.314 | 0.072 |

| Praying location | H = 1.506 | 0.681 | 0.031 |

| Frequency of partial ablution | U = 189.000 | 0.594 | 0.079 |

| Partial ablution repetition | U = 425.500 | 0.028 | 0.310 |

| Frequency of partial ablution repetition | H = 6.785 | 0.079 | 0.138 |

| Partial ablution location | H = 0.600 | 0.741 | 0.012 |

| Full ablution repetition | U = 13.000 | 0.560 | 0.113 |

| Frequency of full ablution repetition | H = 6.832 | 0.077 | 0.139 |

| Frequency of fasting practice | H = 1.120 | 0.772 | 0.023 |

| Self-question if fasting correctly | U = 368.500 | 0.103 | 0.230 |

| Self-question if fasting accepted by God | U = 342.000 | 0.342 | 0.134 |

| Frequency of fasting repetition | H = 1.038 | 0.595 | 0.021 |

| Frequency of suspecting intrusive thoughts related to ritual impurity | H = 3.653 | 0.455 | 0.075 |

| Frequency of attempts to correct suspected ritual impurities | H = 1.933 | 0.586 | 0.039 |

| Blasphemous thoughts | U = 338.500 | 0.379 | 0.124 |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding the holy book | U = 209.500 | 0.534 | 0.089 |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding religious scripts or prophetic hadiths | U = 289.500 | 0.854 | 0.026 |

| Perceived parents’ religiosity | H = 7.912 | 0.095 | 0.161 |

| Perceived self-religiosity | H = 3.146 | 0.370 | 0.064 |

| Frequency of visiting religious places/centers | H = 1.533 | 0.199 | 0.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayoub, W.A.R.; Dib El Jalbout, J.; Maalouf, N.; Ayache, S.S.; Chalah, M.A.; Abdel Rassoul, R. Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with a Religious Focus: An Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7575. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247575

Ayoub WAR, Dib El Jalbout J, Maalouf N, Ayache SS, Chalah MA, Abdel Rassoul R. Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with a Religious Focus: An Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(24):7575. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247575

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyoub, Wissam Al Rida, Jana Dib El Jalbout, Nancy Maalouf, Samar S. Ayache, Moussa A. Chalah, and Ronza Abdel Rassoul. 2024. "Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with a Religious Focus: An Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 24: 7575. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247575

APA StyleAyoub, W. A. R., Dib El Jalbout, J., Maalouf, N., Ayache, S. S., Chalah, M. A., & Abdel Rassoul, R. (2024). Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with a Religious Focus: An Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(24), 7575. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247575