What Will We Learn if We Start Listening to Women with Menses-Related Chest Pain?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- General information—age, medical history of endometriosis, including family history, and presence of chest pain during menstrual cycle. Patients were also asked whether they had been previously diagnosed with pelvic and/or thoracic and/or diaphragmatic endometriosis, and how the diagnosis had been obtained (‘intraoperatively’, ‘radiologically’, ‘other test’, or ‘not applicable’).

- Fertility-related section—history of infertility and pregnancies, including miscarriages.

- Status of hormonal therapy—history of hormonal therapy treatment, hysterectomy and adnexectomy.

- Symptoms present during the menstrual cycle—including chest pain, dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, numbness of a limb, and sensation of irregular heartbeat, during the last 6 menstrual cycles. In the case of receiving hormonal therapy, patients were asked to refer to the period prior to treatment. Patients were also able to provide information about other presented symptoms and the exact age of their onset.

- Regularity of symptoms during menstruation—patients were asked to assess the regularity of previously mentioned symptoms (from 1 to 6 times, or not applicable) during the last 6 menstruations.

- Regularity of symptoms during ovulation—patients were asked to assess the regularity of previously mentioned symptoms (from 1 to 6 times, or not applicable) during the last 6 ovulations. Information that ovulation usually occurs on the 14th day of the cycle was provided.

- Additional questions about chest pain during the menstrual cycle—history of cholelithiasis, correlation with meals or dietary mistakes.

- Characteristics of chest pain during menstrual cycle—pain intensity, pain frequency, painkiller usage, pain-related physical activity limitation, aggravating and alleviating factors.

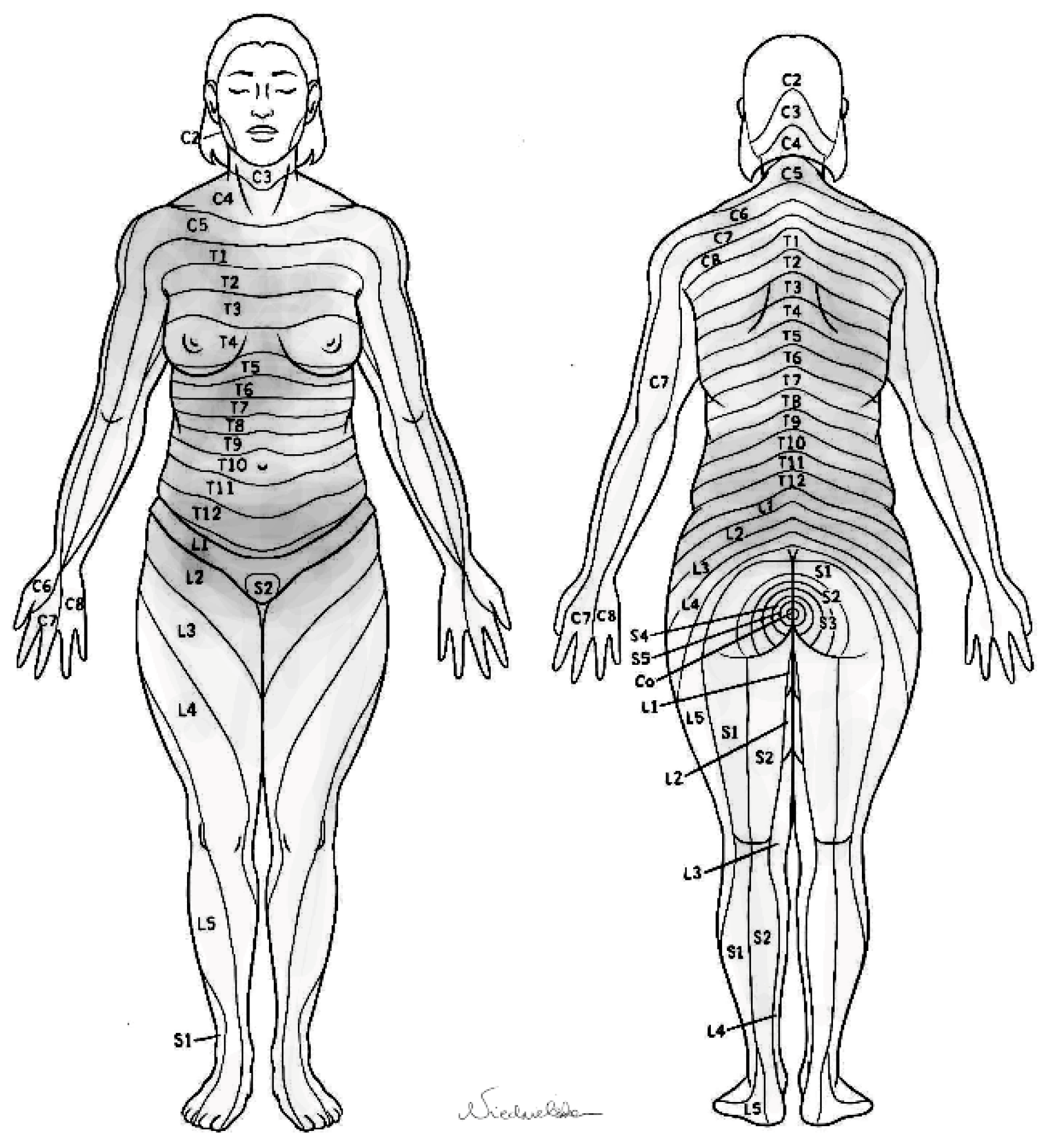

- Pain location—patients were asked to graphically depict the areas that become painful during the menstrual cycle, using a provided dermatome map. Precise instructions were included concerning methods of marking the painful areas and submitting the scheme.

- Comment section—patients could leave additional remarks and comments regarding their condition.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giudice, L.C. Clinical Practice. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttlies, F.; Keckstein, J.; Ulrich, U.; Possover, M.; Schweppe, K.; Wustlich, M.; Buchweitz, O.; Greb, R.; Kandolf, O.; Mangold, R.; et al. ENZIAN-Score, eine Klassifikation der tief infiltrierenden Endometriose. Zentralbl. Gynakol. 2005, 127, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Chvatal, R.; Habelsberger, A.; Wurm, P.; Schimetta, W.; Oppelt, P. Comparison of revised American Fertility Society and ENZIAN staging: A critical evaluation of classifications of endometriosis on the basis of our patient population. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1574–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keckstein, J.; Becker, C.M.; Canis, M.; Feki, A.; Grimbizis, G.F.; Hummelshoj, L.; Nisolle, M.; Roman, H.; Saridogan, E.; Tanos, V.; et al. Recommendations for the surgical treatment of endometriosis. Part 2: Deep endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa002. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhat, C.; Main, J.; Paka, C.; Nezhat, A.; Beygui, R.E. Multidisciplinary treatment for thoracic and abdominopelvic endometriosis. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2014, 18, e2014-00312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhat, C.; Lindheim, S.R.; Backhus, L.; Vu, M.; Vang, N.; Nezhat, A.; Nezhat, C. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: A review of diagnosis and management. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2019, 23, e2019-00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, M.; Roviglione, G.; Farulla, A.; Bertoglio, P.; Clarizia, R.; Viti, A.; Mautone, D.; Ceccarello, M.; Stepniewska, A.; Terzi, A.C. Minimally invasive treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis: A 15-year single referral center’s experience on 215 patients. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 6807–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraín, D.; Suárez, F.; Braun, H.; Chapochnick, J.; Diaz, L.; Rojas, I. Thoracic and diaphragmatic endometriosis: Single-institution experience using novel, broadened diagnostic criteria. J. Turk Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2018, 19, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Koga, K.; Kai, K.; Katabuchi, H.; Kitade, M.; Kitawaki, J.; Kurihara, M.; Takazawa, N.; Tanaka, T.; Taniguchi, F.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of extragenital endometriosis in Japan, 2018. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 2474–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naem, A.; Roman, H.; Martin, D.C.; Krentel, H. A bird-eye view of diaphragmatic endometriosis: Current practices and future perspectives. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1505399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channabasavaiah, A.D.; Joseph, J.V. Thoracic endometriosis: Revisiting the association between clinical presentation and thoracic pathology based on thoracoscopic findings in 110 patients. Medicine 2010, 89, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjański, T.; Sowa, K.; Czapla, A.; Rzyman, W. Catamenial pneumothorax: A review of the literature. Kardiochir. Torakochirurgia Pol. 2016, 13, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visouli, A.N.; Zarogoulidis, K.; Kougioumtzi, I.; Huang, H.; Li, Q.; Dryllis, G.; Kioumis, I.; Pitsiou, G.; Machairiotis, N.; Katsikogiannis, N.; et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 6, S448–S460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, M.; Berg, L.; Gamaleldin, I.; Vyas, S.; Vashisht, A. The management of women with thoracic endometriosis: A national survey of British gynaecological endoscopists. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn. 2021, 12, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Chamié, L.P.; Ribeiro, D.M.F.R.; Tiferes, D.A.; Macedo Neto, A.C.; Serafini, P.C. Atypical sites of deeply infiltrative endometriosis: Clinical characteristics and imaging findings. Radiographics 2018, 38, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobbio, A.; Canny, E.; Mansuet Lupo, A.; Lococo, F.; Legras, A.; Magdeleinat, P.; Regnard, J.-F.; Gompel, A.; Damotte, D.; Alifano, M. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome other than pneumothorax: Clinical and pathological findings. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2017, 104, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quercia, R.; De Palma, A.; De Blasi, F.; Carleo, G.; De Iaco, G.; Panza, T.; Garofalo, G.; Simone, V.; Costantino, M.; Marulli, G. Catamenial pneumothorax: Not only VATS diagnosis. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1156465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augoulea, A.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Christodoulakos, G. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome. Respiration 2008, 75, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, P.O.; Adeniran, A.S.; Adesina, K.T.; Ige, O.A.; Akanbi, O.R.; Imhoagene, A.; Ibrahim, O.; Ezeoke, G.G. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome at University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 24, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, F.; Schwander, A.; Vaineau, C.; Knabben, L.; Nirgianakis, K.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D. True prevalence of diaphragmatic endometriosis and its association with severe endometriosis: A call for awareness and investigation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, T.; Oliveira, M.A.; Panisset, K.; Habib, N.; Rahman, S.; Klebanoff, J.S.; Moawad, G.N. Diaphragmatic endometriosis and thoracic endometriosis syndrome: A review on diagnosis and treatment. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2022, 43, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehade, A.E.H.; Nasir, A.B.; Peterson, J.E.G.; Ramseyer, T.; Bhardwaj, H. Thoracic endometriosis presenting as hemopneumothorax. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2023, 93, 12–16. Available online: https://www.monaldi-archives.org/index.php/macd/article/view/2401 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Pratomo, I.P.; Putra, M.A.; Bangun, L.G.; Soetartio, I.M.; Maharani, M.A.P.; Febriana, I.S.; Soehardiman, D.; Prasenohadi, P.; Kinasih, T. Video-assisted surgical diagnosis and pleural adhesion management in catamenial pneumothorax: A case and literature review. Respirol. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e01123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, A.; Coker, A.; Stamenkovic, S.A. Robotic-assisted thoracic surgery approach to thoracic endometriosis syndrome with unilateral diaphragmatic palsy. Case Rep. Surg. 2023, 2023, 5493232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.Y.; Jung, Y.W.; Shin, W.; Park, M.; Lee, G.W.; Jeong, S.; An, S.; Kim, K.; Ko, Y.B.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Endometriosis-related chronic pelvic pain. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, P.; Gregory, J.; Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Hugon-Rodin, J.; Regnard, J.F.; Chapron, C.; Coste, J.; Golfier, F.; Revel, M.-P. MR diagnosis of diaphragmatic endometriosis. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 3968–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, M.R.; Schenk, W.B.; Nassar, A.; Maimone, S. Thoracic endometriosis presenting as a catamenial hemothorax with discordant video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020, 15, 1419–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillington, G.A. Catamenial pneumothorax. JAMA 1972, 219, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanski, T.; Czapla-Iskrzycka, A.; Pietrzak, K.; Grzybowska, M.E.; Kowalski, J.; Sworczak, K. History of catamenial pneumothorax may increase the risk of pneumothorax related to delivery. Kardiochir. Torakochirurgia Pol. 2024, 21, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigueras Smith, A.; Cabrera, R.; Kondo, W.; Ferreira, H. Diaphragmatic endometriosis minimally invasive treatment: A feasible and effective approach. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 41, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaichies, L.; Blouet, M.; Comoz, F.; Foulon, A.; Heyndrickx, M.; Fauvet, R. Non-traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with liver herniation due to endometriosis: A rare evolution of the disease requiring multidisciplinary management. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 48, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Presentation | Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|

| Age | Median 37 years (22–48) |

| Diagnosed with endometriosis | 96% (88/92) |

| Diagnosed with thoracic endometriosis | 20% (18/92) |

| Diagnosed with diaphragmatic endometriosis | 18% (17/92) |

Method of diagnosis of endometriosis:

| 53% (49/92) 32% (23/92) 21% (19/92) |

| Age of diagnosis of endometriosis | 31.5 (18–46) |

| Presence of chest pain during menstrual cycle | 98% (90/92) |

| Presence of other symptoms but not chest pain or hemoptysis during menstrual cycle | 2% (2/92) |

Laterality of symptoms

| 42% (39/92) 21% (19/92) 37% (34/92) |

| Family history of endometriosis | 25% (23/92) |

Fertility

| 59% (54/92) 21% (19/92) 21% (19/92) |

| Treated for infertility | 34% (31/92) |

How many times was pregnant

| 30% (28/92) 34% (31/92) 24% (22/92) 12% (11/92) |

How many miscarriages

| 76% (70/92) 16% (15/92) 5% (5/92) 2% (2/92) |

| Current hormonal treatment of endometriosis | 57% (40/70) |

Surgical treatment for pelvic endometriosis

| 13% (9/71) 87% (62/71) |

| Diagnosed with gallstones | 5% (5/92) |

| Association of symptoms with food intake | 8% (7/92) |

| Symptoms During Menstruation | Number of Patients with Symptom (%) | Mean Age in Women with Pain [Years] (SD) | Number of Patients Without Pain (%) | Mean Age Women Without Symptom [Years] (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest pain | 88 (96%) | 36.7 (5.2) | 4 (4%) | 31.3 (10.9) | 0.053 * |

| Shoulder pain | 8 (9%) | 36.6 (3.2) | 84 (91%) | 36.5 (5.7) | 0.933 |

| Scapular pain | 10 (11%) | 38.7 (4.3) | 82 (89%) | 36.2 (5.6) | 0.179 |

| Arm pain | 4 (4%) | 35.6 (2.2) | 88 (96%) | 36.3 (5.6) | 0.656 |

| Neck pain | 4 (4%) | 36.5 (6.9) | 88 (96%) | 36.5 (5.5) | 0.990 |

| Numbing | 2 (2%) | 33.5 (0.7) | 90 (98%) | 36.5 (5.6) | 0.447 |

| Dyspnea | 62 (67%) | 36.7 (5.6) | 30 (33%) | 36.1 (5.4) | 0.609 |

| Cough | 48 (52%) | 36.6 (5.1) | 44 (58%) | 36.3 (6.0) | 0.749 |

| Hemoptysis | 5 (5%) | 41.0 (5.1) | 87 (95%) | 36.2 (5.5) | 0.059 * |

| Tension in the chest | 4 (4%) | 36.5 (5.1) | 88 (96%) | 36.5 (5.6) | 0.995 |

| Stunned limb | 30 (33%) | 38.4 (5.4) | 62 (67%) | 35.5 (5.4) | 0.021 ** |

| Pouring liquid sensation | 12 (13%) | 38.8 (5.3) | 80 (87%) | 36.1 (5.5) | 0.126 |

| Popping sensation | 11 (12%) | 38.5 (4.6) | 81 (88%) | 36.2 (5.6) | 0.186 |

| Pressure | 2 (2%) | 37.0 (4.2) | 90 (98%) | 36.4 (5.6) | 0.892 |

| Pressure and weight | 7 (8%) | 37.6 (4.5) | 85 (92%) | 36.4 (5.6) | 0.586 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marjanski, T.; Czapla, A.; Niedzielska, J.; Grono, L.; Bobula, J.; Świątkowska-Stodulska, R.; Milnerowicz-Nabzdyk, E. What Will We Learn if We Start Listening to Women with Menses-Related Chest Pain? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092882

Marjanski T, Czapla A, Niedzielska J, Grono L, Bobula J, Świątkowska-Stodulska R, Milnerowicz-Nabzdyk E. What Will We Learn if We Start Listening to Women with Menses-Related Chest Pain? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092882

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarjanski, Tomasz, Aleksandra Czapla, Julia Niedzielska, Lena Grono, Jagoda Bobula, Renata Świątkowska-Stodulska, and Ewa Milnerowicz-Nabzdyk. 2025. "What Will We Learn if We Start Listening to Women with Menses-Related Chest Pain?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092882

APA StyleMarjanski, T., Czapla, A., Niedzielska, J., Grono, L., Bobula, J., Świątkowska-Stodulska, R., & Milnerowicz-Nabzdyk, E. (2025). What Will We Learn if We Start Listening to Women with Menses-Related Chest Pain? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092882