1. Introduction

The nature of relationship between tourism and agricultural sectors has always been one of the main concerns in tourism development. Since tourism destinations are generally subject to rapid changes particularly in developing tourism spots, balancing the relationship between the tourism and agricultural sectors from a competitive and contrasting state to an interactive and complementary state is a complex issue in spatial planning. In rural and suburban areas, which face the growth of tourist activities, the local community experiences the benefits of tourist activities in addition to agricultural activities, and in the maturity stages of tourism growth, this can cause the choose of one instead of the other. In fact, the purpose is to abandon agricultural activities because of the perceived benefits of tourism [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In some cases, the conflict between these two sectors is such that even if tourism grows in the form of agro-tourism, it can still cause farmers to give up their activities [

5]. Additionally, as Sun et al. [

6] argued many traditional agricultural systems are now under severe pressure from globalization and inadequate government intervention which has led to loosing more farms and unwilling of the farmers to developing agro-tourism activities due to unfamiliarity as well as lack of government support [

6]. In this regard, in Europe, especially since the 1980s, attempts have been made to optimize the balance between tourism and agriculture through the strategy of agro-tourism [

7]. However, in some countries such as Greece, in a few cases, agro-tourism has led to the weakening and destruction of agriculture [

7]. In China the disappearance of longstanding agricultural heritage systems due to economic shifting from agriculture sector to service sector, mainly tourism development, has been a main concern during the last decade [

6] because of the resource policies in China that has prioritized service and industrial sectors as economic development driving forces. For Zuo and Zhong [

8] the market price reform together with the privatization on coal mining are the most important driving forces that have had positive effect on provincial economic growth in China [

8]. They examined impacts of resource policies on the resource growth relation in China that reverse of the resource curse [

8]. As regards resource curse and its effects on agriculture sector, Behera and Mishra [

9] investigated interrelationship between the abundance of natural resources and economic development in India and concluded that the resource curse exists in the Indian states because of weak institutions and policies that has had detrimental effects on agriculture sector as a natural resource abundance [

9].

Nevertheless, a series of related research show that the relationship between tourism and agriculture is more complex and affected by a set of multifaceted structural and individual factors [

10], so that this relationship ranges from a state of conflict (competition on water resources, land and labor force) to a state of complementation (supply of crops and agricultural landscapes to tourists) [

11,

12].

Although less research has been done in recent years to examine the causes of conflict between tourism and agriculture, this issue has been the focus of studies for the past decade along with the growth of tourist activities and the intensification of its negative environmental consequences.

Studies by Weaver and Lawton [

13] and Belisle [

14] on the relationship between tourism and agriculture in the Caribbean show that farmers have not been able to adapt agricultural products to meet the specific needs of the tourism sector and benefit from the tourism sector [

13,

14]. This was also confirmed by Koutsouris et al. in the mountainous regions of Greece [

15]. In this regard, Belisle [

14] pointed out several barriers hindering the growth of local agricultural production in line with the growth of tourist activities. He divided these factors into five main categories, including physical, behavioral, economic, technological, and marketing barriers [

14].

Fleischer and Tchetchik [

16], reviewing previous research, showed that the relationship between tourism and agriculture is weakening in several destinations around the world. Therefore, the growth of tourist activities has led to decrease of agricultural lands and reduced agricultural labor force [

16]. Compared to tourism, the low capacity of the agricultural sector in terms of creating job opportunities and generating income for the local community is one of the main weaknesses emphasized in most of the studies [

1,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. As an instance, tourism has been at the center of land use conflicts on the Mediterranean coast of Spain [

22]. Tyrakowski’s study showed that the problem of reducing high-yield (high-quality) agricultural land as a result of the growth of tourism in that area is a serious matter. Thus, the agricultural labor force abandoned the farms and preferred working in the tourism-related services [

22].

Latimer [

23] believes that tourism attracts land, labor force and capital from other activities, including agriculture, which faces many problems in creating local employment. Regarding the competition on land, he refers to cases in Nusa Dua Basin in Bali, Indonesia and Cancun in Mexico, which have become important tourist destinations by abandoning traditional agriculture. This has been confirmed in the research of Su et al. [

24] on the historical-agricultural area of Huaba in Hebei Province, China. “Small farmers can earn more money by engaging in tourism, and in some cases, make windfall profits by selling well-located lands to land brokers”, wrote Sunyer [

25] about reducing the agricultural lands in Cape Loic, Catalonia, Spain [

19,

25,

26].

Land brokers in the field of tourism are key players in realizing the change of agricultural land use to tourism as soon as possible by encouraging farmers to sell land and offer it in a profitable market for the construction of tourism facilities. This has been confirmed in Ibza’s research [

27] on the northern coasts of the Mediterranean [

22] and in McTagart’s research in Bali, Indonesia [

28]. The rapid rise in land prices makes it possible for farmers, who are always faced with a variety of risks in their activities, to earn millions of overnight incomes (as a chance) [

18]. On the other hand, increasing the rent of agricultural lands and, consequently, increasing the cost of agricultural production is another issue related to this subject [

29].

Government and land management authorities play an important role in the relationship between the tourism and agricultural sectors. Weakness and inefficiency of land management systems, especially in developing countries with the lack of support of the agricultural sector and inability to manage tourism development are among the fundamental reasons for the squeeze of the agricultural sector and widespread changes in the agricultural land use to tourism [

30,

31]. Moreover, reduced marketing activities and storage facilities for agricultural products due to the lack of government support should be added to these factors [

21]. The results of the research by Wang and Yatsumoto [

32] in three different provinces of central China show that the one-sided action of local governments in confiscating the lands of poor farmers for tourism development has led many of these farmers to change their jobs. Thus, it has led to deep contradictions between the agrarian economy and the tourism-based industry in the three villages studied in central China [

32]. Analyzing the Chinese government’s policies, Scott et al. [

33] consider the lack of attention to the living of poor farmers in the process of developing tourism and neglecting the need of their participation as other important factors affecting the farmers’ reluctance in continuing agricultural activities, reducing agricultural lands and increasing tourist activities. In this regard, other important factors that researchers have emphasized are the lack of coordination between the organizations in charge of tourism and agriculture planning and the lack or inefficiency of policies to support the land resources causing the abuse of tourism developers and land brokers [

31,

34,

35].

In some cases, contrary to the above policies, strong government support of the agricultural sector has led to its continued survival in competition with tourism [

34]. Pinto-Correia et al. [

34] in their research in the Southeast Europe and Portugal concluded that due to the conservative views of farmers against the protection of natural landscapes and the existence of strong laws regarding the protection of agricultural lands, the tourism sector has lost the competition to the agricultural sector. Based on their field research, government financial support of the agricultural sector, farmers’ confidence in the government’s ability to protect them, securing the agricultural land ownership, and controlling the land use change through a strong planning system have caused this to happen [

34].

Apart from government attitude to agriculture and tourism sectors, local communities’ perception towards tourism development is important contributing factor in the relationship between tourism and agriculture, since the positive perceptions might be detrimental for agriculture sector. In this regard, using descriptive statistics and principal component analysis, Harun et al. [

36] analyzes the attitudes and perceptions of the local residents from the Kurdistan Regional Government and concluded that tourism is seen as a development sector during the last years. Its positive impacts are better perceived than the negative ones, mainly because it offers more recreational opportunities [

36]. The issue of importance of local community’s attitude and perception is confirmed by Abdel Maksoud et al. [

37] and by Michael et al. in their research from Dubai region, UAE [

38].

Developing tourism facilities such as expansion of second homes is amongst other contributing factor in transformation of agriculture sector to the tourism sector. For instance, in his research on 213 land use conflicts in the coastal areas of Denmark, Hjalager [

39] concluded, that the expansion of second homes as well as the construction of hotels and tourist accommodation centers were the most important factors in changing the agricultural and horticultural use in the coastal areas of the country supported by the municipalities and government officials of Denmark [

39]. Consistent with the results of the above study, Benge and Neef [

40], focusing on the conflict between tourism and traditional water-based agriculture on the Indonesian island of Bali, concluded that diverting water from agricultural areas to tourist hubs using political and economic power has led to growing injustice in the distribution of water between economic sectors, especially agriculture. This issue, along with the extreme and unregulated exploitation of water resources by the tourism sector, has caused the water consumption rate to be much higher than its renewable capacity. As a result, the land potential of this island, which has flourished for centuries with fertile soils and has been prosperous for the past 10 years has changed in favor of the tourism sector. Subsequently, these factors have led to a decline in agricultural production and lack of farmers’ motivation in favor of the development of tourist activities by influential economic and political companies in Indonesia [

40]. The results of Kuvan and Akan’s research on Belek coastal area in Antalya, Turkey [

41] also confirm the key role of governmental organizations in managing land and water resources between agricultural and tourism sectors [

41].

In relation to the weakness of the agricultural sector against the attractions of the tourism sector, the dispersion of land ownership and the prevalence of the retail ownership system and consequently the low access to technology for small farmers can be another effective variable [

25]. In fact, the small size farmlands with low revenue-generating capacity are extremely vulnerable to rapid external changes such as a large wave of tourism demand and related constructions.

Examining the causes of the conflict between tourism and agriculture in the countries on the northern coasts of the Mediterranean, Hermans [

26] argued that although tourism has caused the increase of income and attracted labor force from other sectors such as agriculture, the younger generation’s reluctance to work in agricultural sector cannot be under the influence of tourism. According to Hermans, this issue is rooted in a more general phenomenon, which is “degradation in the status (prestige) of agricultural activity” [

26]. In this regard, Su et al. [

24] in a study on the reasons for the downfall of the agricultural sector against the increased motivation for tourism or migration to cities in Hebei Province, China, found that the lack of motivation of the young generation to continue their family (agricultural) activities is one of the effective factors in reducing the agricultural activities and, consequently, their replacement with tourism uses [

24]. In addition, the reluctance of parents to continue agricultural activities by their children has been another factor intensifying this process.

In addition, in some studies, the structure of international tourism organizations has been identified as one of the barriers to local agricultural suppliers. Hotels owned or operated by foreigners may have strong links with trans-regional and international agricultural suppliers, and as a result, tend to rely on trans-regional and even transnational suppliers rather than local suppliers [

17].

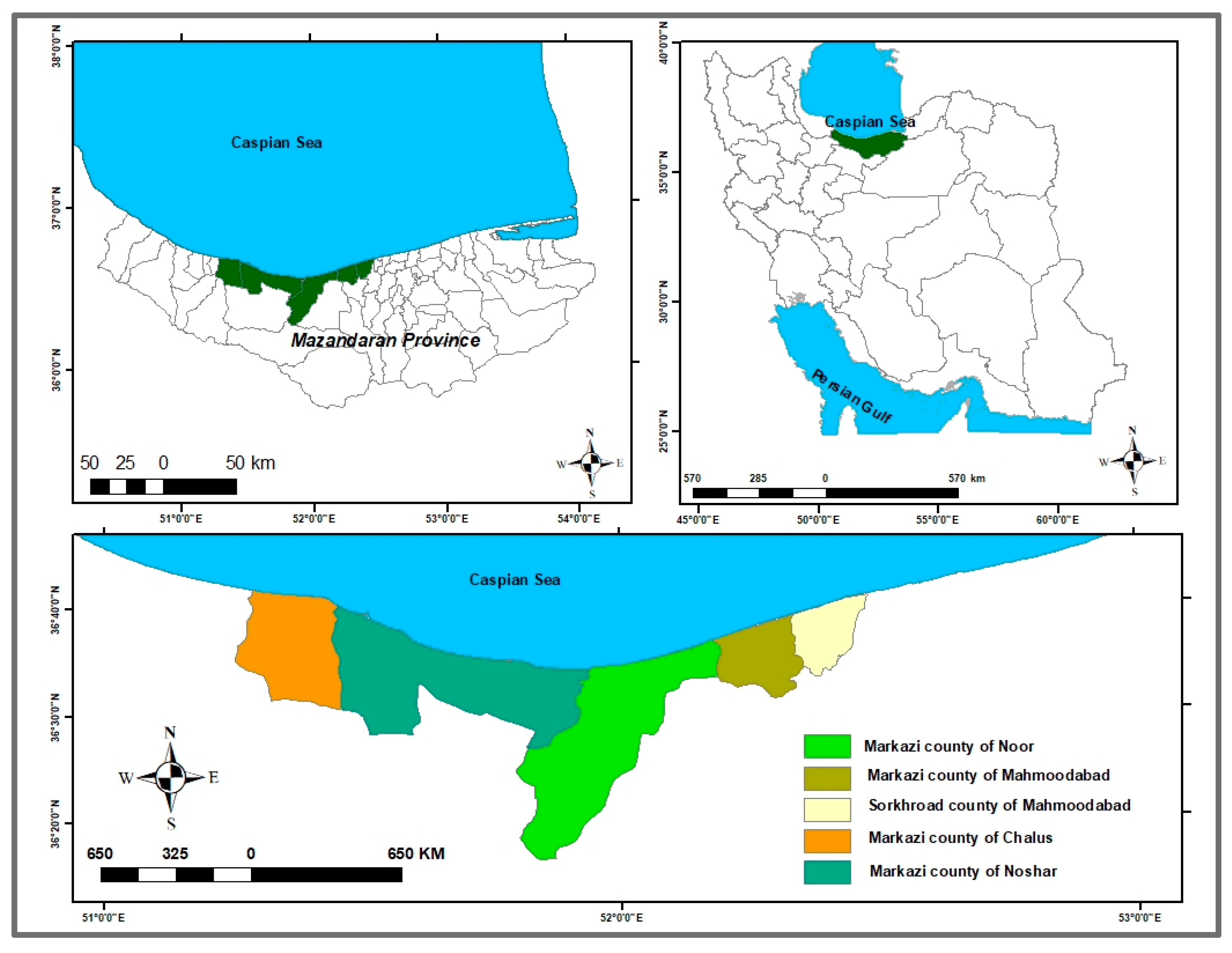

In sum, reviewing of the current literature shows that the nature of the relationship between tourism and agriculture is different, depending on the political, administrative, and socio-cultural contexts. This issue is highly sensitive in developing countries since the share of agriculture sector is considerably high and the land use management system is weak. Therefore, the farming community is extremely vulnerable to any external changes such as the growth of tourism. Given the wide range of changes in the agricultural land use to the other competing uses such as tourism is a serious challenge to achieving the goals of sustainable national and global development. Therefore, addressing the fundamental factors affecting the relationship between tourism and agriculture is one of the main research concerns in developing countries like Iran. At the same time, due to the lack of research on the causes of conflict between the agriculture and tourism sectors, especially in the Middle East, this study attempts to investigate this controversial relationship and provide evidence from a different political and social context, namely an Islamic developing country, Iran. Based on the abovementioned problem, the main purpose of this study is to investigate the reasons of changing the agricultural land use to tourism and the abandonment of the labor force from agricultural activities in areas that have quickly become tourist destinations. In doing so, the main research questions are: what are the main factors in the changes of agriculture land use to tourism? Why did the farmers sell their farms or abandon their job? What is the role of the regulation and executive systems in the process of land use change? This article consists of the following sections: In the

Section 1, the previous research is reviewed, the research problem and objectives are stated. In the

Section 2, the study area and methods and techniques of data collection and analysis are described. In the next parts of the article, the most important research results are presented and discussed, and finally in the

Section 5, while summarizing the results and synthesizing them, referring to the limitations of the research, topics are suggested for further research.

3. Results

The interviewed population of this study, including farmers and government organization experts in charge of land management in the agricultural administration of the studied areas described the key factors and areas causing the sale of agricultural lands and change of land use from agriculture to tourism. Their descriptions are categorized in the following.

3.1. Low Capacity of the Agricultural Sector in Creating Job Opportunities and Generating Income Compared to Tourism

In the northern regions of Iran, especially in the studied area, the main agricultural activities include rice cultivation, which is done traditionally in a large part of the region. This economic sector has not been able to update and modernize all the stages from cultivation to crop production. Thus, the relative income of farmers in these areas has always been less than the income of other economic sectors such as industry and services. Most of the interviewed farmers mentioned that the relatively low income of the agricultural sector was the main and first reason for selling the lands and abandoning their agricultural activity. As an interviewed father and son, who sold their farm and work (as unskilled worker) in a construction company said:

My father and grandfather and I were all farmers. Despite the hardships of traditional farming, which requires full-time and long-term work on the land, we have never been able to lead a prosperous life, and provide such a life for our children. In fact, we have always been in economic difficulties. Working on the farms never provided us with enough income. However, at the same time we had no expertise in other fields and we continued to do it traditionally.

The family size is of high in the rural areas studied, especially among farmers. Traditionally, having a son was considered a great luck because a son could be a labor force on the land in the future. Due to the traditional activity and low efficiency of agricultural activities, the per capita income of the farmer household is low against the high costs of large size households. One of the interviewees as a retired famer who sold his farm and opened a new grocery store reported:

I have six children and I had to pay for my children’s education in addition to the usual cost of living to make a better future for them. Due to rising inflation, the costs of living and the children’s education also increased. Although my children helped me with farming, this did not increase our income, as our land area was the same while our family grew. I was really under economic pressure. It really had a negative effect on my family’s peace of mind. My farmland was two hectares and I had four sons and three daughters. Despite the hard work of farming in the hot and humid summers of this region, I was struggling to meet the needs of my family, and when my children grew up and were looking for work, I saw that this limited land did not have the capacity to support our new extended family. Therefore, my children had to look for another job and I had to retire due to my age. Thus, the best decision in that situation was to sell the land at a great price to tourism investors.

According to field observations and interviews with agricultural experts, one of the reasons for the low per capita income of farming households was the small area of agricultural land, i.e., the dominance of the smallholder system. As two official experts from Nowshahr and Noor Agricultural Organizations said:

Farmers in these areas have low incomes, mainly due to the small size farms. The average farm size in these areas is less than one hectare. In fact, the low area of agricultural lands limits the income of farmers, which in turn prevents the use of new technologies in the agricultural sector, since farmers are not able to provide the necessary capital for it. On the other hand, investing in such technologies in the level of small lands has no economic justification at all. Moreover, the large size of the farming households doubles the problem, and you will find that these families are always facing economic hardships.

In our study of the reasons for the small size of the agricultural lands in the study area, three experts from Noor, Nowshahr and Mahmoud Abad Agricultural Organizations point to the Law of Inheritance in Iran derived from Islamic Law:

According to the Law of Inheritance (Ghanoone-Ers) in Iran, the father’s property is divided between the sons (with a larger share) and daughters (with a smaller share than the sons) in a certain proportion. In the agrarian society, land is the main property divided between the children. We see that the land area is being fragmented from one generation to the next, and this causes the agricultural lands to shrink and, consequently, the farmers’ incomes to decrease to a level where there is no economic justification for working on the agricultural land.

According to interviews with experts of land management in the agricultural administrations of Chalous, Nowshahr and Mahmoud Abad, the agricultural sector in the study area has a much lower capacity in terms of creating job opportunities and generating income compared to the tourism sector. According to one interviewee with decades of experience from the land management department of Chalous, “selling land and investing in tourism or investing in financial markets is much more profitable than farming which is generally traditional and hard and requires experience and capital. Tourism services, on the contrary, do not require long expertise and large capital, and the work is much easier and more profitable than the agricultural activities”.

3.2. Lax Land Use Laws and Lack of Inter-Organizational Coordination in Law Enforcement

The beginning of domestic mass tourism activities and the demand for a second home in Iran dates back to the years after the end of the 8-year war between Iraq and Iran [

52]. Especially since the 1990s, one of the main reasons for the destruction of agricultural lands and turning them into second homes or bare lands has been the defect and weakness of land use management laws. In an interview, two experts from the Agricultural Organization of Noor and Nowshahr explained that:

In 1995, to manage and control the growth of demand for second homes and prevent the land use change from the agricultural lands and orchards to tourism sectors, the ‘Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards’ was approved by the parliament. Contrary to the title and purpose of this law, the results of its implementation severely changed and destroyed the use of agricultural lands and orchards. According to this law, the requirements of the implementation of Land Reform Law (1962), considered as important deterrents in maintaining land integrity in the Land Reform Law, were abolished, while under the Land Reform Law, farmers received land reform documents and in the transaction of buying and selling lands, the seller (farmer) had only the right to transfer his land to another farmer and not for any other activity. The only exception was for the clause of Article 19 of the Land Reform Law, mentioning that if a public benefit project had a greater socio—economic benefit than agriculture, the relevant commission would agree to change the agricultural use and implement the project. The removal of this clause from the Land Reform Law of 1962 significantly intensified the process of changing the land use and selling the agricultural lands to non-farmers and tourism construction.

Explaining the weaknesses of land management laws and regulations, two experts from the Department of Agriculture of Mahmoud Abad and Noor explained:

Existence of deficiencies in the laws has effectively prevented the Department of Agriculture from taking action to abandon the change of the agricultural lands. One of these deficiencies can be seen in Article 147 of the amendment on the Law on Registration of Documents and Properties. According to this law, all agricultural lands and orchards on which construction has taken place before 1990 can receive a title deed. Thus, the profiteers first segregated their agricultural lands or orchards overnight (illegally). They built a wall around it and constructed a small warehouse on the land, then made preliminary agreement with fake dates before 1990 and traded the land. Therefore, such lands were not considered under the 1995 Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards, and their owners could apply for a title deed and a construction preliminary agreement.

The enactment of the 1995 Law on the Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Garden, especially in the study area, was a deterrent to preserve of the agricultural land use. Moreover, due to the lack of proper implementation and enforcement of a reasoned and firm sentence against violators, this law intensified the process of land use change. In the Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards (1995), in addition to abolishing the restrictions of the Land Reform Law of 1962, according to Article 3, a person who changes the use of agricultural lands and orchards and performs construction must pay taxes determined in Article 4 in cash, and also pay fine up to three times as much as the certified cost of the land (expert-determined price). One of the experts of the Department of Agriculture of Chalous explains the negative dimension of this law as follows:

The problem of this law, in addition to its nature, which is the possibility of buying the law, has also been in its implementation. In this way, the violators introduced by the county Department of Agriculture to the court were either forgiven by the judges or the amount of the fine was always set less than 3 times. The judges’ justification for determining the fine less than three times as much as the current price was that the law states ‘up to three times’, meaning that an amount can be set up to three times as much as the amount of the fine.

An expert from the Department of Agriculture of Nowshahr, with 20 years of experience and a master’s degree in agriculture explains:

Many experts and I from the Department of Agriculture and related researchers disagree with the content of Article 3 of the 1995 Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards. This article actually makes it possible for the law to be bought and sold. If changing the use of valuable agricultural lands causes irreparable damage to the environment and the economy, and then serious legal barriers should be considered, not by making it possible to buy. The cheapness of the law and even the bribery paved the way for the widespread activity of land dealers, which has become a loophole for many dealers to bribe the judicial experts and judges to impose lesser fines and even change the court judgment in their own favor.

According to another expert from Noor, another problem between the Department of Agriculture and the court was with the land use assessment by certified experts who were sent to the site by the court to determine the type of land use being claimed. Most of the relevant experts had non-agricultural expertise, and the results of the assessments on the type of land use were mostly wrong and reported in favor of the violator. In practice, the complaint of the Department of Agriculture was deadlocked.

In the case of agricultural lands within the urban areas, the issue of weak law enforcement is again problematic since an easy way is there for purchasing the law or lowering the fines. In this regard, the Law on Article 100 of the Municipalities Commission has the same nature as Article 3 of the 1995 Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards, providing the possibility of paying fines for construction violations and land use changes within urban areas. In this regard, some researches show that a large part of the municipal revenues is related to constructions and land use violations, and this figure sometimes constitutes more than 70% of the municipal reve nues [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Therefore, despite the numerous laws preventing the land use change and construction violations (such as Article 100 of the Municipal Law), there is no practical and serious obstacle against the land use violators. The experience of one of the interviewed experts from Department of Agriculture of Nowshahr is as follows:

Municipalities are heavily dependent on construction revenue, mainly land segregation, land use change and construction related violations. Therefore, they do not pose a serious obstacle to violators. However, officials encourage brokers and developers to do so by issuing light fines. Unfortunately, I have to say that this is not the end of the matter. Real estate brokers and land developers bribe the officials for escaping heavy fines and expanding their illegal activities, thereby making huge profits. In fact, this law has greatly encouraged the development of corruption and the purchase of land use legislators and lawmakers. I think this issue has deeper negative consequences than the issue of land use change itself.

The above findings show that in addition to the shortcomings of the existing laws, lack of policy and consistent cooperation between the bodies involved, especially the Department of Agriculture and the judiciary, the influence of brokers and the spread of corruption have been other key factors in changing the agricultural lands to tourism.

3.3. Weakness of the System of Registration of Documents and Properties

Another factor intensifying the change of the agricultural lands in the studied areas are the weakness of the official registration system of documents and properties and the lack of timely cadastral maps throughout the country, especially in the study area. In general, in Iran and specifically in the study area, an integrated cadastral system has not been built and many lands and real estate transactions are done in the form of a preliminary agreement, i.e., a temporary contract between the buyer and the seller without official registration in the Real Estate Registration Office. It should be noted that this document is the first stage of transferring real estate and land from the seller to the buyer, and in the next stage, the buyer is obliged to refer to the Real Estate Registration Office to receive the official title deed. However, many transactions between the real estate brokers and land developers are done only on the basis of preliminary agreements. Therefore, due to the lack of official registration of the agreement, both parties are allowed to buy and sell multiple properties informally without paying taxes or cash duties. It is important to note that the preliminary agreement (although it is an unofficial form of transaction) is trusted and widely used by major real estate brokers and even ordinary people.

The problem posed by this method of property transfer in the fight against agricultural land use change is described by one of the interviewees:

According to the Law on Preservation of Agricultural Lands and Orchards, in lawsuits between the Department of Agriculture and the defendant in the court, one must first prove one’s ownership of the land (i.e., determine the owner of the land). In many cases due to lack of access to the official land title deeds and due to failure to register one’s ownership in the official database of the registration of documents and properties, the Department of Agriculture cannot prove the ownership of the offender to the court, and the offender, taking advantage of this legal vacuum, claims that he is not the owner of the land at all. Hence, the court session and the subject of the complaint is practically canceled because the ownership of the land owner cannot be proven. Only in this way, many of the complaints of the Department of Agriculture from people who have tried to change the use of agricultural land and make it barren failed.

3.4. Lack of Effective Government Support of the Agricultural Sector

According to field interviews with farmers, most of them believed that one of the main factors leading to the weakening of the agricultural sector in the region was the variable and inefficient policies of the government in support of agriculture. In this regard, one of the interviewees from Nowshahr, who sold main parts of his farm, explains:

Every four years, a government with a new cabinet takes the power (even if the president is the same for eight years). We are faced with new policies every four years. For example, the main policy of one government is to support domestic production and prevents the excessive import of agricultural products, especially rice, and urges the farmers to develop arable lands and invests more in agricultural infrastructure. In another government, due to the problem of water shortage and drought, the cultivation of high-water consuming crops, such as rice should be limited since it is not cost-effective at all, and it is better to import such crops from abroad. Now imagine that the farmers have got loans from the banks and bought new agricultural equipment, and now the government’s policy is against them.

Two interviewed farmers from Chalous, who sold their land and opened a domestic food restaurant, explain that:

In addition to natural risks, we are always worried about the agricultural policies of the next government or the next minister. It seems that we are trifled. A minister imports a lot of agricultural products from abroad, which is much cheaper than the price of our products, and this is a kind of struggle against the local farmers, isn’t it? Shall we compete with the government? Or should the government support us to make the agriculture sustainable? What can a small farmer like us do against the government’s policies? Finally, we sold our lands like the rest, and by the way, we are now in better prosperity than before. Now let the government think about providing the products demanded by the country.

According to field observations and interviews, farmers in the region find government policies inefficient and inconsistent. Many farmers believe that increasing the prices of agricultural inputs (raw materials for production), insufficient bank loans, lack of storage facilities for agricultural products, lack of proper distribution channels for agricultural products and the dominance of profiteers of agricultural products that really benefit from the agricultural sector are the samples of government’s inefficient policies.

3.5. Rapid Rise in Land Prices

With the growth of tourist activities, especially the construction of the second homes, land prices will rocket [

52,

58]. In the study area have increased rapidly so that land prices have risen by 40,000 times as much as their previous prices between 1996 and 2006 [

35]. The sudden rise in land prices, driven by growing demand for a second home on the Caspian coasts, has discouraged many farmers from continuing to work on the land. As a farming family who sold their farm, deposited in bank (with 20% interest rate), and bought two taxies, explained in an interview:

We worked on the farms for years with an income that never covered our living expenses. Now that the land is getting more expensive, if we only sell a part of our land, which has no legal restrictions, we can use it to start a new business in services, or even in the worst case, if we only deposit it in the bank and use its interest, we can earn at least 5 times as much as our annual income from agriculture.

It is noteworthy that bank deposits, which usually give people an annual interest rate of about 18 to 20%, are one of the popular options for conservative investors in Iran. It can be said that most of the interviewed farmers referred to the rapid and significant rise in land prices as an important factor in abandoning the agricultural activities and selling the farmlands. According to field observations, many farmers sold farmlands, built modern homes for themselves and their children, bought expensive cars, and deposited large sums of money in banks.

3.6. Farmers and Their Children’s Attitudes towards Agricultural Activity and Welfare Level

Since the 1990s, the influx of millions of domestic tourists and the construction of thousands of tourist complexes and second homes in the study area have not only led to widespread spatial changes but have also profoundly affected the local community’s attitude towards their life style. Interviews with farmers who have sold their land to tourists or are willing to sell it show that the head of the household is under pressure from the economic needs of his children and is dissatisfied with his income compared to working on the land. Another interviewed group mentioned that people’s rising expectations and changing lifestyles in the area are motivations for the sale of lands. In an interview with a farmer and his children from Sorkhroud County, who opened a grocery store and bought two modern cars and a new house by selling their farm, they explained:

We have been farmers for many years with hard work and low income. When we compared our lives with the prosperous tourists who traveled here, we realized that we were always in trouble. While there is another way than agriculture and it is possible to live more comfortably with the same prosperity as tourists, why shouldn’t we live in a modern house? Why shouldn’t we have a good car? How long shall we live in difficulty? The price of land has increased so much that by selling it, we can provide a prosperous life for ourselves and our families just like the tourists. Why should we be in trouble? The government and officials who do not care about us. We need to be supported and our national production and economy should be considered. Why don’t we care for ourselves?

Field observations and interviews with young job seekers in the region show that the young generation and job seekers in the region are not even willing to make their lives on the basis of agricultural activities and live like their fathers. One of the young job seekers from a farmer family in Chalous explained his attitude towards agricultural activity as follows:

What I have experienced in my family as a farmer family and what I have seen around me is that farming has never brought me to the level of well-being that I imagined. Although this job has problems and difficulties, it does not generate income even at the level of very simple service and tourism jobs. It also has a low social prestige. I have never been proud of my family because of having such a low-prestige job in the Iranian society. I do not want such a future for myself and my children.

In general, the results of interviews in the study area clearly show that farmers have a negative attitude towards their job and they cannot provide the desired welfare for themselves and their families. This issue is more prominent among young people because for many of them, agriculture is a hard job with low income and at the same time with low social prestige. Therefore, they do not want to base their future on this job (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The result of this study showed that the nature of the relationship between tourism and agriculture (complementary or competitive) is influenced by a network of factors rooted in the macro features of land management system, government policies and the influence of tourism brokers and developers. Simultaneously, as Plana-Farran and Gallizo [

58] concluded, it is influenced by micro and individual factors such as the attitude of farmers’ families, especially the young labor force [

58]. The findings of this study, in contrast to studies emphasizing the complementary and constructive relationship between tourism and agriculture in the form of agro-tourism, have provided evidence on the destructive effect of tourism on agricultural activities. A review of the past research has shown that although this is more common in many developing countries, research from European destinations has reported on the destructive impact of tourism on agriculture, even with pro-agro-tourism policies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

7,

13,

14,

15].

The main results of this study showed that the factors affecting the relationship between tourism and agriculture can be divided into three main categories, including: 1. Factors related to the land management system and government development policies, 2. Tourism developers and brokers, and 3. Characteristics of local agriculture and farmer families. According to the research findings, the traditional and small-scale agricultural sector has been weakening for decades in the absence of effective government support. In this regard, shrinking land size (under the influence of inheritance law), increasing family size and stable efficiency had a negative impact on the capacity of the agricultural sector to create job opportunities and generate income. This feature, as the weakness of agriculture at the time of the growth of tourism in the region, has played an important role in abandoning the agricultural activity and even selling the farmlands to tourism developers. Such a serious competition between the tourism and agricultural sectors over labor and other resources such as land and water has been reported in other studies from different European regions to the Caribbean [

1,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Analyzing the government’s policies in causing a conflict between the agricultural and tourism sectors, research studies by Al Haija in Oman [

31], Kuvan and Akan in Antalya, Turkey [

41], Wang and Yotsumoto in China [

32], Scott et al. in China [

33], Benge and Neef [

40] in Bali [

33] and Roman et al. in Poland [

59], showed that the government’s commitment to the agricultural sector, especially for small lands managed by poor farmers, has been superficial. This is in line with the findings of this research. They also added that governments have supported investment on tourism with the aim of developing rural areas, and regardless of traditional agricultural activities, they have weakened this economic sector at the time of the growth of tourism. In contrast, the results of the research by Pinto-Correia et al. (2014) in Southeastern Europe and Portugal showed the effective role of government support of the agricultural sector, leading to the protection of agricultural lands from being changed to tourism sectors [

34].

In the study area, the low capacity of the traditional agricultural sector in creating job opportunities and generating income has been one of the most important factors affecting the change of agricultural land use or reducing the rate of activity in the agricultural sector. Meanwhile, the tourism sector has been welcomed by the local community with the potential to generate higher income and create more job opportunities. While agricultural activity has been more difficult and required more capital and experience, tourism services with less capital and less experience and hard work quickly became the focus of farmer families, especially the young job seekers. Similar results have been reported by Tyrakowski (1986) off the coasts of Spain, Latimer (1985) in Nusa Dua Basin in Bali and Cancun in Mexico, Saxena and Ilbery (2008) in the Caplioc Basin, and Su et al. (2018) in China.

In addition, the results showed that the nature of land use laws, and how to implement and monitor them (as key features of the land management system) can affect the process of land use change (from agriculture to tourism). In the cases investigated in this study, changing the nature of the regulations, despite their predefined goals, not only failed to protect valuable land resources, but also provided a way for rapid changes in agricultural land use to tourism. In this regard, by presenting the results of research on 213 contradictions between the agricultural and tourism sectors off the coast of Denmark, Hjalager showed that the weakening of laws or changes in the regulations in favor of tourism development led to the dominance of investment in tourism and extensive land use changes off the coast of Denmark [

39].

Other features of the land management system in the study cases are the lack of alignment and cooperation between organizations involved in land management, the lack of an integrated land ownership registration system, the prevalence of preliminary note transactions without official registration, and insignificant fines for violators, which make the land use change easier. The dependence of urban and rural management organizations on revenue from land use change tariffs and related fines was another factor creating a serious obstacle to controlling the destruction of agricultural lands. Another aspect of the results of this study showed that corruption along with the influence of tourism brokers and developers in decision-making have played a serious role in the process of changing the use of agricultural lands to tourism sectors. Similar reports have been presented by Almeida et al. in their research off the coast of Troia-Melides. In their study, the role of trading firms and construction companies influencing decisions made on the development of tourism at the cost of destroying, and weakening the agricultural sector was explained and confirmed [

35].

In the cases studied in this research, the growth of land prices, among other factors, had a serious impact on the attitude of farmers, especially young people, to continue agricultural activities. This issue, which occurred due to the growth of tourists’ demand and the widespread activity of tourism brokers and developers, accelerated the process of selling agricultural lands and leaving agricultural activity in the communities. This finding was confirmed in the studies by Bryden (1973) in the Caribbean, Hermans (1981) on the northern coasts of the Mediterranean, Kuvan and Akan in Belek coastal region of Antalya, and Almeida et al. on the coasts of Troia-Melides [

35]. In line with the above issue, another factor affecting the abandonment of agricultural activities and the sale of agricultural lands was the attitude of the local community, especially the youth, toward the need for higher welfare in life and their negative attitude toward agricultural activity as a job with low social prestige.

This issue has also been approved in the studies by Hermans (1981) [

26] and Su et al. (2018) [

24], showing that the lack of motivation of young people for doing agricultural activities against the attractiveness of tourist activities is a serious factor weakening the agricultural sector at the time of the growth of tourism.

This research is of high importance for several reasons. First, in recent years, the importance of this research has been marginalized, and most of the relevant research has emphasized the complementary relationship between tourism and agriculture while the results of this study showed that in different political, administrative and cultural contexts, tourism could have a contradictory effect on the preservation of agricultural lands. On the other hand, a handful of related studies have been published in the context of Islamic countries in the Middle East, and this research can contribute to the tourism and agricultural literature by providing evidence on different political, administrative and cultural contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the factors affecting the conflicting relationship between tourism and agriculture. Although this issue has been less considered by researchers in recent years, it has been reported in numerous studies, especially in the 1990s. In order to investigate the issue in more depth, this research applied an interpretive approach along with qualitative methods in the process of data collection and analysis. Using unstructured interview technique, two main groups of the target community were interviewed. The first group included farmers who had sold all or a significant part of their arable land to the tourism sector, and the second group included experts from the Department of Agriculture who had a long expertise of working in the land management sector.

The results of this study showed that the relationship between tourism and agriculture is a complex matter under the influence of various structural and individual factors that can benefit tourist activities and weaken and even destroy the agricultural sector if neglected. In the studied cases, a set of weaknesses and inefficiencies in land management and agricultural systems has ultimately led to a widespread change of agricultural lands to tourism by affecting the living standards of farmers and their attitudes. More detailed studies from the point of view of the target community showed that the agricultural sector is in a weak position compared to the tourism sector in terms of creating job opportunities and generating income due to its traditional nature and small size feature. However, according to the results, agricultural activity requires higher initial capital, is harder, and requires more experience and knowledge than tourism services. In addition, changes in the land use laws that made it easier to change the use of arable lands to other uses, along with numerous legal loopholes that made it possible to violate the regulations caused the destroy of the agricultural lands and paved the way for tourism development. Lack of an integrated land ownership registration system throughout the country, prevalence of unregistered preliminary note transactions, light fines for violators, lack of cooperation and alignment between the courts and the agricultural administration against violators who attempt to change the land use, dependence of urban and rural municipalities on the revenues from fines for land use change and illegal constructions and corruption in the land management decision-making system have been the features of the land management system in the studied cases that facilitate the process of change of the agricultural lands to tourism. In addition to these weaknesses, the instability of government policies towards the agricultural sector has become another major factor influencing the conflict between tourism and agriculture. The results of this study revealed that the continuous change of government policy regarding the import of agricultural products, the influence and domination of agricultural traders and the lack of development of infrastructure in the agricultural sector have caused confusion and even serious financial losses. In addition to these factors, farmers also face serious environmental threats.

With the growth of tourist activities and the rapid growth of demand for the construction of second homes in the studied cases, land prices increased significantly over a five-year period. This increase in the price of land provided some farming families with the opportunity of obtaining large amounts of capital by selling the land and financing for their future and that of their children. Due to the increase in the number of tourists in the study areas and the familiarity of the local communities with the lifestyle of tourists, who were mainly from the affluent to the middle class, farmers’ attitudes toward life and welfare changed. Gradually, working on the land was no more a value for many farming families, especially young people. In contrast, agriculture was believed to be a low-level job in their community. This attracted many young workers to tourism services. Thus, they gave up agriculture job. In fact, with the provision of large-scale capital gains from land sales, people’s wishes to have a more prosperous and comfortable life and were reluctant to work on the agricultural lands. Thus, changing agricultural lands to tourism sectors intensified one more time.

The findings of this study pointed out that two economic sectors of tourism and agriculture are in competition with each other on land resources, labor and other natural resources such as water. Hence, the land management system incompetence and the neglect of the development policies of the potential competition between these two economic sectors can lead to the development of tourism at the cost of destroying the agricultural lands. Therefore, in areas with a similar political, administrative and social context to the cases studied in this research, the issue of tourism development and its link with agriculture should be presented cautiously considering the efficiency of structural factors and individual micro-characteristics. At the end, these results deliver a message to provincial authorities and policy makers that development of tourism in rural and agricultural areas involves effective coordination and cooperation between various formal and informal stakeholders. Formulating and implementing of the sustainable land-use policies or every spatial development are chiefly depend on all stakeholders’ perception and behavior.

At the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study had several limitations, e.g., restrictions in wider and longer access to the target groups and setting a time for doing the interviews. Because of the COVID-19 restrictions, the authors could not take advantage of focus group and had to meet every single target person or family separately. In addition, most of the farmers (target groups) did not have the skill of working with social media platforms such as Skype or WhatsApp to run an online meeting. Beside of the COVID-19 situation, although the snowball sampling method helped to find suitable subjects quicker but the authors found some kind of bias while in some cases just definite number of subjects were refereed by people. Furthermore, before the meeting arrangement and interview (that took days of the research) we could not make sure that the referred person will fit to the research or not. Another difficulty was even after referrals, some of the subjects were not cooperative and refused to participate in the research process. The authors spent time more than normal situation by finding proper subjects and continued data gathering process to rich a theoretical saturation level. Another point is that due to the nature of qualitative methods, a limited community was used to collect data. This limitation can be developed with the help of quantitative methods and higher participation of the target community. Therefore, other researchers are suggested to study the subject of this research in societies with different political, social and cultural contexts by combining qualitative and quantitative methods. In this regard, mix of the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, Path Analysis and Grounded Theory are suggested.