Impact of Cultivar, Processing and Storage on the Mycobiota of European Chestnut Fruits †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

2.2. General Inspection of Chestnut Samples

2.3. Isolation of Fungi from Chestnuts

2.4. Molecular Identification of Fungal Isolates

2.5. Fungi Guild Classification

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

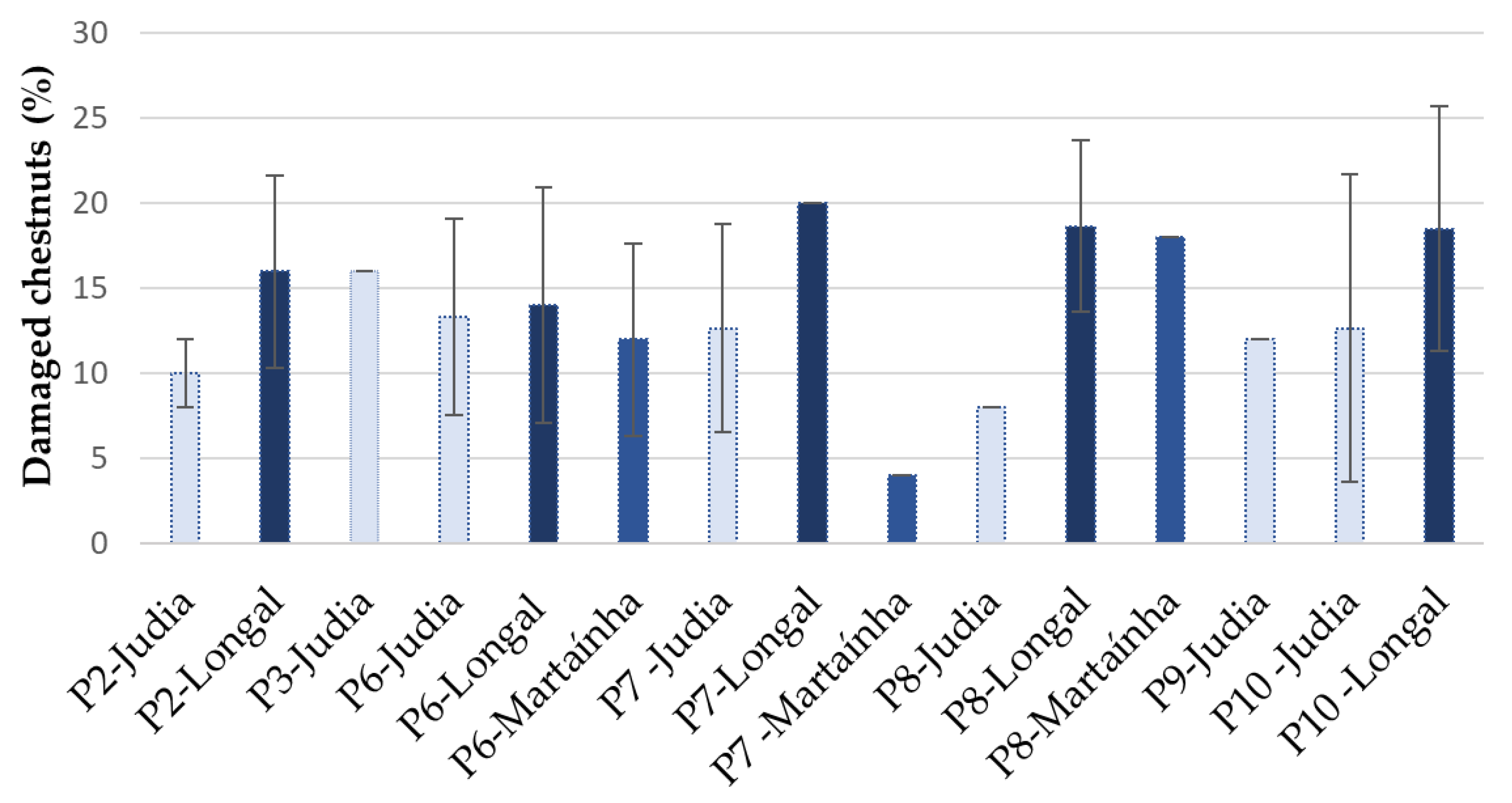

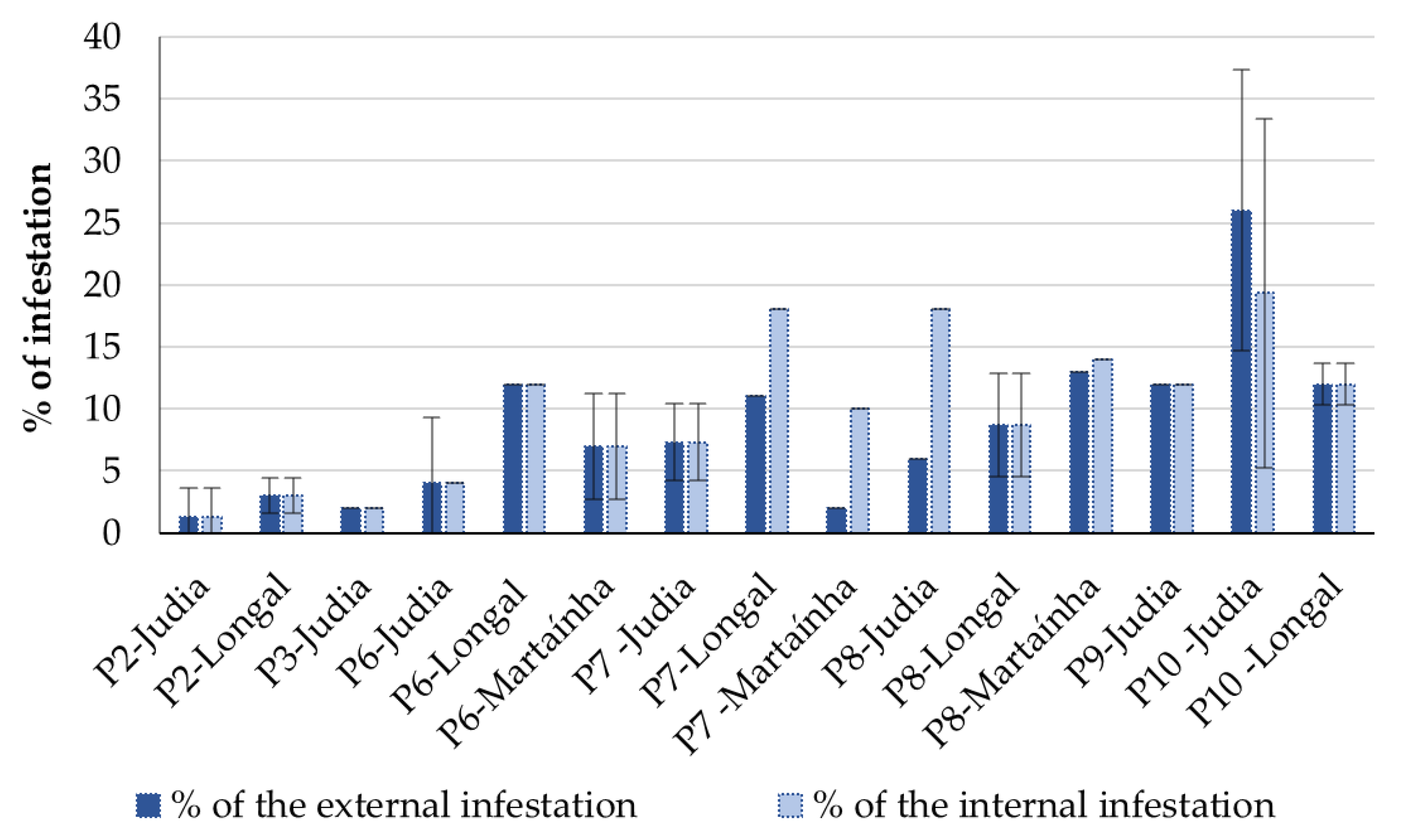

3.1. Chestnut Overall Inspection

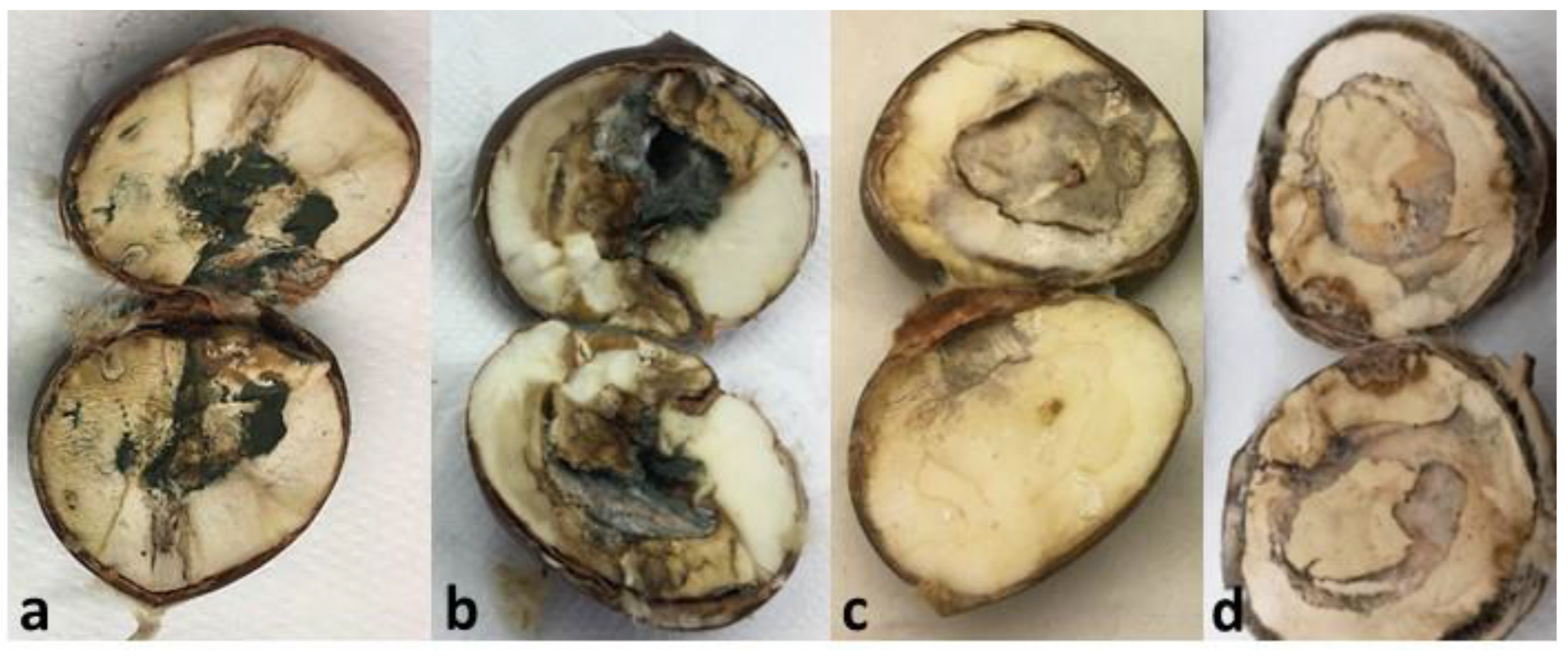

3.2. Level of Chestnut Rot

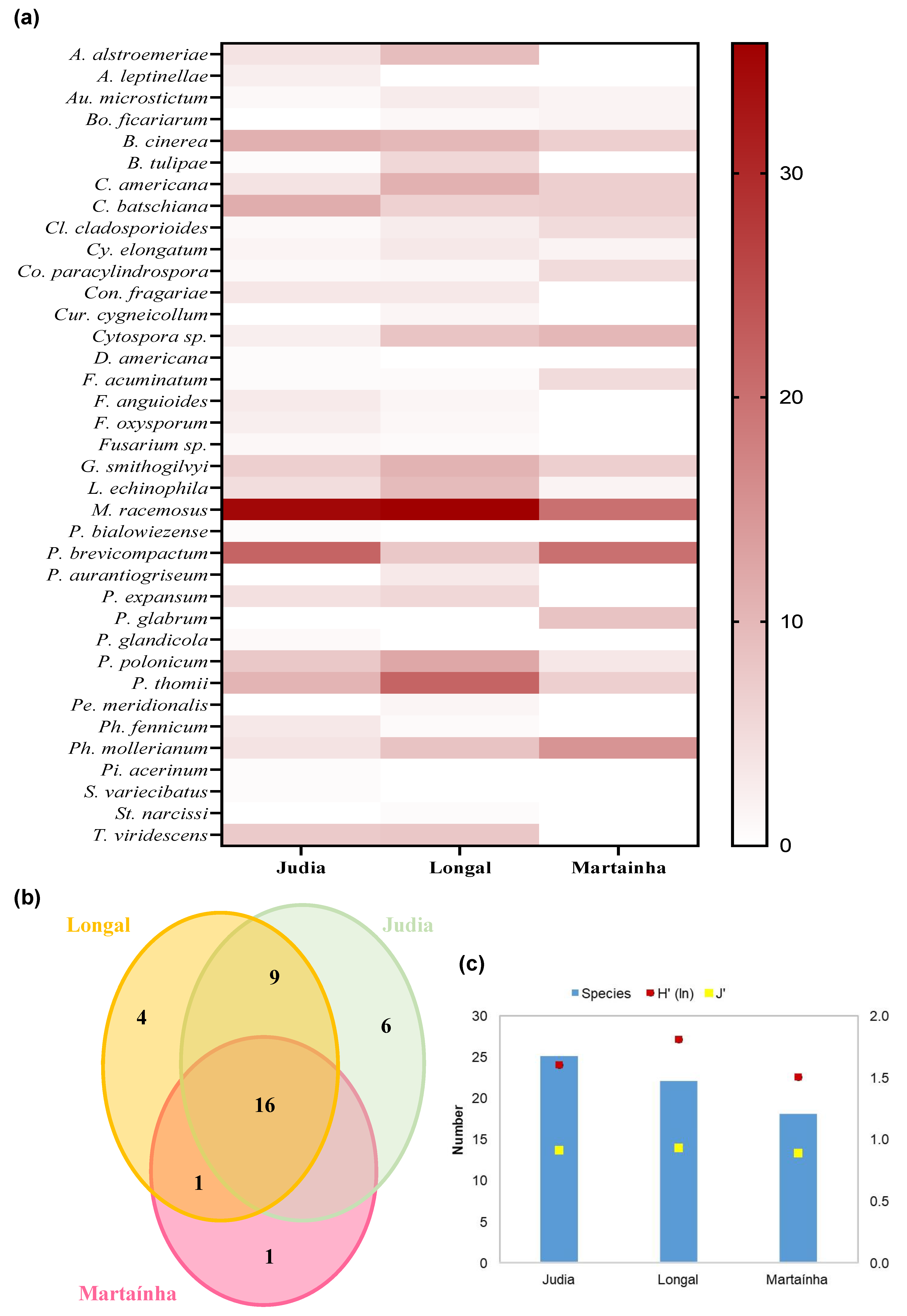

3.3. Fungal Species Frequency and Incidence

3.4. Fungal Species Richness and Diversity among Chestnut Varieties

3.5. Mold Guilds According to Stage Processing and Chestnut Variety

3.6. Mold Community Analysis According to Processing Stage and Chestnut Variety

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves, B.; Borges, O.; Costa, H.S.; Bennett, R.; Santos, M.; Silva, A.P. A metabolite of chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) upon cooking: Proximate analysis, fiber, organic acids, and phenolics. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.C.B.M.; Bennett, R.N.; Rosa, E.A.S.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V. The composition of European chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) and association with health effects: Fresh and processed products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE. Estatísticas Agrícolas 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N. Mycobiota and mycotoxins of almonds and chestnuts with special reference to aflatoxins. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N. Incidence and diversity of the fungal genera Aspergillus and Penicillium in Portuguese almonds and chestnuts. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 137, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wells, J.M.; Payne, J.A. Toxigenic Aspergillus and Penicillium Isolate from Weevil-Damaged Chestnuts. Appl. Microbiol. 1975, 30, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lione, G.; Danti, R.; Fernandez-Conradi, P.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V.; Lefort, F.; Marques, G.; Meyer, J.B.; Prospero, S.; Radócz, L.; Robin, C.; et al. The emerging pathogen of chestnut Gnomoniopsis castaneae: The challenge posed by a versatile fungus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 153, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, W.S.; Allen, A.D.; Dooley, L.B. Preliminary studies on Phomopsis castanea and other organisms associated with healthy and rotted chestnut fruit in storage. Australas. Plant Pathol. 1997, 26, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Paolacci, A.; Vannini, A. Endophytism of Sclerotinia pseudotuberosa: PCR assay for specific detection in chestnut tissues. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jermini, M.; Conedera, M.; Sieber, T.; Sassella, A.; Schärer, H.; Jelmini, G.; Höhn, E. Influence of fruit treatments on perishability during cold storage of sweet chestnuts. J. Sci. Food Agri. 2006, 86, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N.; Jermini, M.; Conedera, M. Effects of the harvest method on the infestation of chestnuts (Castanea sativa) by insects and molds. J. Phytopathol. 2007, 155, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis-González, I.R.; Guyer, D.E.; Fulbright, D.W. Quantification and identification of microorganisms found on shell and kernel of fresh edible chestnuts in Michigan. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4514–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.C.; Agri, M. The life cycle, pathology, and taxonomy of two different nut rot fungi in chestnut. Austral. Nutgrow. 2008, 22, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.C.; Ogilvy, D. Nut rot in chestnuts. Austral. Nutgrow. 2008, 2, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, S.; Valentino, D.; Visentin, I.; Tamietti, G. An epidemic of Gnomonia pascoe on nuts of Castanea sativa in the Cuneo area. In Proceedings of the 1st European Congress on Chestnut—Castanea 2009. Eds. G. Bounous and G.L. Beccaro. Acta Hortic. 2010, 866, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, I.; Gentile, S.; Valentino, D.; Gonthier, P.; Tamietti, G.; Cardinale, F. Gnomoniopsis castanea sp. nov. (Gnomoniaceae, Diaper- Thales) as a causal agent of nut rot in sweet chestnut. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 94, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Maresi, G.; Oliveira Longa, C.M.; Turchetti, T. Brown rot on nuts of Castanea sativa Mill: An emerging disease and its causal agent. iForest 2013, 6, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shuttleworth, L.A.; Liew, E.C.Y.; Guest, D.I. Survey of the incidence of chestnut rot in south-eastern Australia. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2013, 42, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, M.A.; Rai, M. Biological and phylogenetic analyses evidencing the presence of Gnomoniopsis sp. in India causing canker of chestnut trees: A new report. Indian For. 2013, 139, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dennert, F.G.; Broggini, G.A.L.; Gessler, C.; Storari, M. Gnomoniopsis castanea is the main agent of chestnut nut rot in Switzerland. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2015, 54, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, L.A.; Guest, D.I. The infection process of chestnut rot, an important disease caused by Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) in Oceania and Europe. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overy, D.P.; Seifert, K.A.; Savard, M.E.; Frisvad, J.C. Spoilage fungi and their mycotoxins in commercially marketed chestnuts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 88, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, H.H. Influence of soil temperature and moisture on infection of wheat seedlings by Helminthosporium sativum. J. Agric. Res. 1923, 26, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N. Toxic reagents and expensive equipment: Are they really necessary for the extraction of good quality fungal DNA? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 66, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- White, T.J.; Burns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocol: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfald, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molec. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. Primer v5: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E Ltd., Ed.; Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- StatSoft. STATISTICA (Data Analysis Software System); Version 10; StatSoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.statistica.com/en/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Costa, R.; Ribeiro, C.; Valdiviesso, T.; Afonso, S.; Costa, R.; Borges, O.; Carvalho, J.S.; Costa, H.A.; Assunção, A.; Fonseca, L.; et al. Variedades de Castanha Das Regiões Centro e Norte de Portugal; Instituto Nacional dos Recursos Biológicos: Oeiras, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barreira, J.C.M.; Casal, S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Pereira, J.A. Nutritional, fatty acid and triacylglycerol profiles of Castanea sativa Mill. Cultivars: A Compositional and Chemometric Approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2836–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.C.; Bennett, R.N.; Rosa, E.A.S.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V. Industrial processing effects on chestnut fruits (Castanea sativa Mill.). 2. Crude protein, free amino acids and phenolic phytochemicals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 2613–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nagar, A.; Elzaawely, A.A.; Taha, N.A.; Nehela, Y. The antifungal activity of gallic acid and its derivatives against Alternaria solani, the causal agent of tomato early blight. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shahir, A.A.; El-Wakil, D.A.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Youssef, N.H. Bioactive compounds and antifungal activity of leaves and fruits methanolic extracts of Ziziphus spina-christi L. Plants 2022, 11, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.M.; Payne, J.A. Mycoflora and Market Quality of Chestnuts Treated with Hot Water to Control the Chestnut Weevil. Plant Dis. 1980, 64, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morales-Rodriguez, C.; Sferrazza, I.; Aleandri, M.P.; Valle, M.D.; Mazzetto, T.; Speranza, S.; Contarini, M.; Vannini, A. Fungal community associated with adults of the Chestnut gallwasp Dryocosmus kuriphilus after emergence from galls: Taxonomy and functional ecology. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yang, S.; Litao, P.; Zeng, K.; Feng, B.; Jingjing, Y. Compositional shifts in fungal community of chestnuts during storage and their correlation with fruit quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 191, 111983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodriguez, C.; Bastianelli, G.; Caccia, R.; Bedini, G.; Massantini, R.; Moscetti, R.; Thomidis, T.; Vannini, A. Impact of ‘brown rot’ caused by Gnomoniopsis castanea on chestnut fruits during the post-harvest process: Critical phases and proposed solutions. Fungal Biol. 2022, 102, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prencipe, S.; Siciliano, I.; Gatti, C.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Botta, R.; Spadaro, D. Several species of Penicillium isolated from chestnut flour processing are pathogenic on fresh chestnuts and produce mycotoxins. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciegler, A. Fungi that produce mycotoxins: Conditions and occurrence. Mycopathologia 1978, 65, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.A.I.; de Felice, D.V.; Ianiri, G.; Pinedo-Villa, C.; De Curtis, F.; Castoria, R. Two rapid assays for screening of patulin biodegradation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coton, M.; Dantigny, P. Mycotoxin migration in moldy foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 29, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4899-8409-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tziros, G.T.; Diamandis, S. Sclerotinia pseudotuberosa as the cause of black rot of chestnuts in Greece. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 100, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shuttleworth, L.A.; Guest, D.I.; Liew, E.C.Y. Fungal Planet Description Sheet 107: Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi. Persoonia 2012, 28, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A.; Gorton, C.; Rees, H.; Webber, J.; Pérez-Sierra, A. First report of Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi causing lesions and cankers of sweet chestnut in the United Kingdom. New Dis. Rep. 2017, 35, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coleine, C.; Stajich, J.E.; Pombubpa, N.; Zucconi, L.; Onofri, S.; Selbmann, L. Sampling strategies to assess microbial diversity of Antarctic cryptoendolithic communities. Polar Biol. 2020, 43, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M.; Escosura-Muñiz, A.; Merkoçi, A. Biosensors for plant pathogen detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 93, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ventura-Aguilar, R.I.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Mendoza-Acevedo, S.; Bosquez-Molina, E. Nanomaterials for designing biosensors to detect fungi and bacteria related to food safety of agricultural products. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 195, 112116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Krewer, G.W.; Ji, P.; Scherm, H.; Kays, S.J. Gas sensor array for blueberry fruit disease detection and classification. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 55, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquanta, L.; Albanese, D.; De Curtis, F.; Malvano, F.; Crescitelli, A.; Di Matteo, M. Rapid assessment of gray mold (Botrytis cinerea) infection in grapes with a biosensor system. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Liang, G.; Tian, H.; Sun, J.; Wan, C. Electronic Nose-Based Technique for Rapid Detection and Recognition of Moldy Apples. Sensors 2019, 19, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chalupowicz, D.; Veltman, B.; Droby, S.; Eltzov, E. Evaluating the use of biosensors for monitoring of Penicillium digitatum infection in citrus fruit. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 311, 127896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-H.; Li, X.-M.; Zhu, D.-H.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, L.-Q. The diversity and dynamics of fungi in Dryocosmus kuriphilus community. Insects 2021, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačániová, M.; Sudzinová, J.; Kádasi-Horáková, M.; Valšíková, M.; Kráčmar, S. The determination of microscopic fungi from chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Fruits, leaves, crust and pollen. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2010, 58, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muñoz-Adalia, E.J.; Rodríguez, D.; Casado, M.; Diez, J.; Fernández, M. Fungal community of necrotic and healthy galls in chestnut trees colonized by Dryocosmus kuriphilus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae). iForest 2019, 12, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aragona, M.; Haegi, A.; Valente, M.T.; Riccioni, L.; Orzali, L.; Vitale, S.; Luongo, L.; Infantino, A. New-Generation Sequencing Technology in Diagnosis of Fungal Plant Pathogens: A Dream Comes True? J. Fungi 2022, 8, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, D.F.; Rossman, A.Y. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. 2022. Available online: https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Jiang, N.; Yang, Q.; Fan, X.-L.; Tian, C.-M. Identification of six Cytospora species on Chinese chestnut in China. MycoKeys 2020, 62, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scott, J.A.; Wong, B.; Summerbell, R.C.; Untereiner, W.A. A survey of Penicillium brevicompactum and P. bialowiezense from indoor environments, with commentary on the taxonomy of the P. brevicompactum group. Botany 2008, 86, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitt, J.; Hocking, A. Fungi and Food Spoilage; Blackie Academic and Professional: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Summerell, B.A.; Groenewald, J.Z. Foliar pathogens of eucalypts. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 94, 125–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Samuels, G.J.; Ismaiel, A.; Voglmayr, H. Disentangling the Trichoderma viridescens complex. Pers. Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2013, 31, 112–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possamai, G. Podridão da Castanha em Trás-os-Montes: Caracterização Morfológica, Ecofisiológica e Molecular do Agente Causal Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi. Master’s Dissertation, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Bragança, Portugal, 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10198/23171 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

| Code | Processing Stage | Storage Period (Days) | Sampled Varieties (Replicas) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2 | sterilized by hydrothermal bath (45 °C, 30 min) and immediately sampled | 0 | Judia (3) Longal (2) |

| P3 | sterilized by hydrothermal bath (45 °C, 30 min) after storage | 15 | Judia (1) |

| P6 | sampled immediately after reception, without sterilization | 0 | Judia (3) Longal (3) Martaínha (2) |

| P7 | stored without sterilization and sampled after storage | 15 | Judia (3) Longal (1) Martaínha (1) |

| P8 | stored without sterilization and sampled after storage | 30 | Judia (1) Longal (3) Martaínha (1) |

| P9 | stored without sterilization and sampled after storage | 45 | Judia (2) |

| P10 | sterilized by hydrothermal bath (45 °C, 30 min) but rejected after manual selection | 0 | Judia (3) Longal (4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, P.; Driss, J.O.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Sampaio, A. Impact of Cultivar, Processing and Storage on the Mycobiota of European Chestnut Fruits. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111930

Rodrigues P, Driss JO, Gomes-Laranjo J, Sampaio A. Impact of Cultivar, Processing and Storage on the Mycobiota of European Chestnut Fruits. Agriculture. 2022; 12(11):1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111930

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Paula, Jihen Oueslati Driss, José Gomes-Laranjo, and Ana Sampaio. 2022. "Impact of Cultivar, Processing and Storage on the Mycobiota of European Chestnut Fruits" Agriculture 12, no. 11: 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111930

APA StyleRodrigues, P., Driss, J. O., Gomes-Laranjo, J., & Sampaio, A. (2022). Impact of Cultivar, Processing and Storage on the Mycobiota of European Chestnut Fruits. Agriculture, 12(11), 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111930