Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Relevant Literature

2.1. Overview of Rural Displacement

2.2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

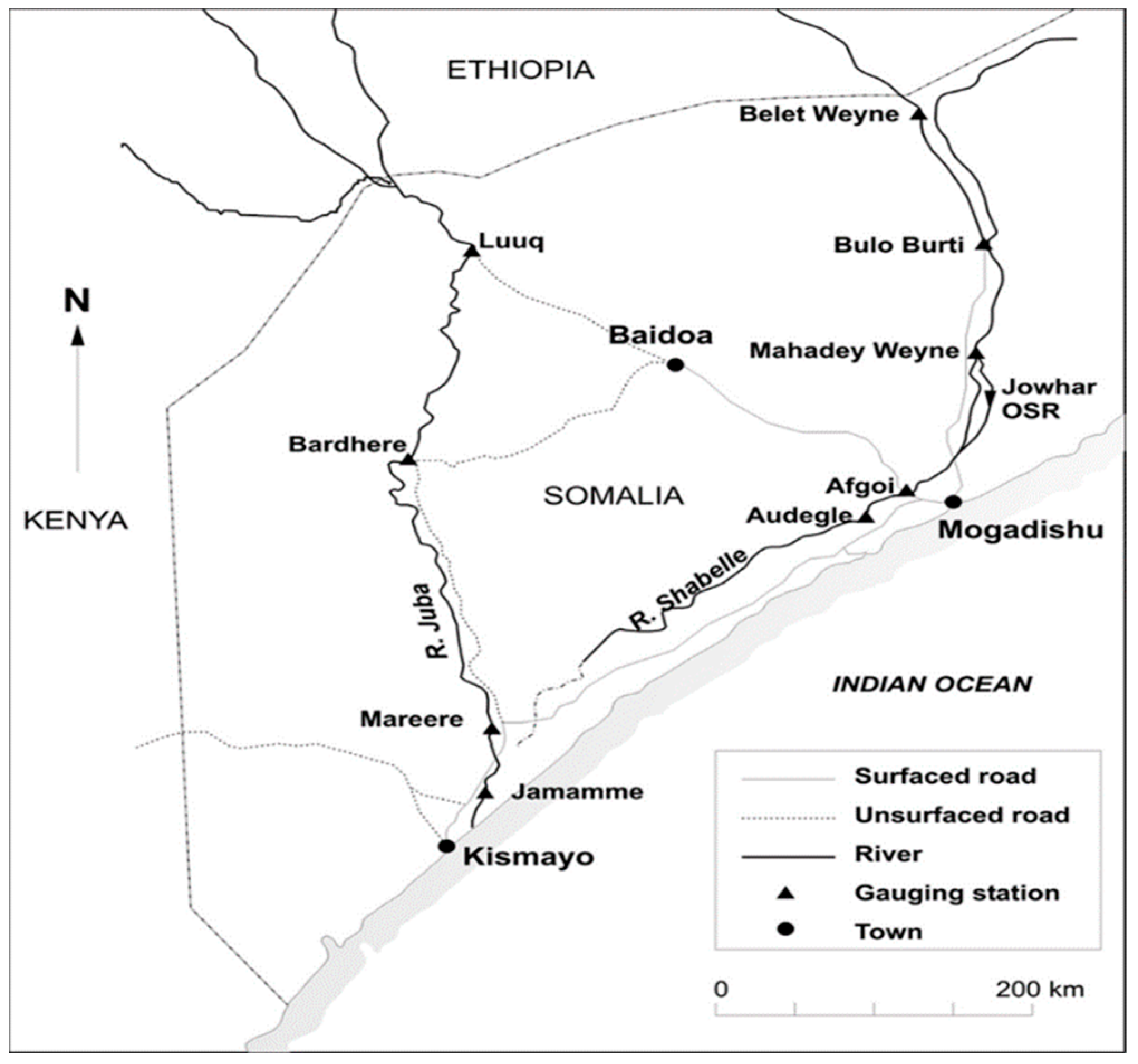

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Research Design

4. Research Findings and Discussion

4.1. Historical Patterns of Displacement in Somalia

4.1.1. Major Crises in Somalia and Their Causes and Consequences

4.1.2. Clan Dynamics and Social Relations in Somalia

4.2. Emprical Evdience

4.2.1. Impacts of Displacement on Livelihoods

4.2.2. Survival Strategies of IDPs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- A.

- FGD guide

- 1.

- What is your major source of livelihood? (please describe in detail)

- 2.

- How has displacement affected your livelihood activities so far?

- 3.

- What are your current livelihood activities?

- 4.

- What are some of the causes of your displacement?

- 5.

- Are some of these causes, the reason why you’ve become IDP? (please elaborate)

- 6.

- How did you use your land before displacement? (only for those who had land or access to land before displacement)

- 7.

- What was your livelihood activity before losing land?

- 8.

- How did you cope before displacement/what were your coping mechanisms?

- 9.

- Why did you seek shelter in alternative areas or camps as IDPs?

- 10.

- Do the camps offer you a safe heaven? And what are your general experiences at the IDP camp?

- 11.

- How do you cope at the camps or in your current place of settlement?

- 12.

- How has displacement affected your household assets and living conditions?

- B.

- Interview questions for gatekeepers

- 1.

- How long have the IDPs have been living in this camp?

- 2.

- What kind of services do you provide to the IDPs?

- 3.

- How is your relationship with the IDPs?

- 4.

- Do they deal with aid agencies directly or aid comes to them through you?

- 5.

- Who gave the IDPs this plot of land to occupy?

- 6.

- What are some of the main challenges IDPs face in this camp?

- 7.

- Do you help them address conflict within the IDP communities?

- 8.

- How is the security of the camp maintained?

- 9.

- Are the IDPs independent for running the day-to-day issues of the camp

- C.

- Interview questions for humanitarian organizations:

- 1.

- What are the major forces that displaced these people from their original residences?

- 2.

- What kind of assistance do you provide with them?

- 3.

- How often do you receive new arrivals?

- 4.

- Do they talk about going back to their places of origin?

- 5.

- What kind of support do you give to those who are willing to return to their places?

- 6.

- Do humanitarian organizations get overburdened to provide assistance?

- 7.

- How do you integrate new migrants and the host communities?

- 8.

- What kind of obstacles do you encounter in your line of duties?

- 9.

- Are humanitarian organizations prepared to respond to influx of new arrivals of IDPs?

- 10.

- Do you think about the perception of the people toward to the support you provide?

References

- George, J.; Adelaja, A. Armed Conflicts, Forced Displacement and Food Security in Host Communities. World Dev. 2022, 158, 105991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.E.; Dhamruwan, M.; Carrico, A.R. Displacement and Degradation: Impediments to Agricultural Livelihoods among Ethnic Minority Farmers in Post-War Sri Lanka. Ambio 2023, 52, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN World Food Programme WFP and UNEP Bolster Global Food and Water Security|World Food Programme. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-and-unep-bolster-global-food-and-water-security (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine Conflict on Land Use across the World. Land 2022, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnassi, M.; El Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for Global Food Security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkendal, T.; Otto, C.; Schewe, J.; Jägermeyr, J.; Konar, M.; Kummu, M.; Watkins, B.; Puma, M.J. Grain Export Restrictions during COVID-19 Risk Food Insecurity in Many Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beasley, A.M. Acts of Violence: Understanding Neoliberalism and Culturally-Constructed Fear in the History of Mexican Immigration to the United States. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Sacramento, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights Council. Global Trends Report 2022; United Nations Human Rights Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies Record 36 Million Africans Forcibly Displaced. Available online: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/record-36-million-africans-forcibly-displaced-is-44-percent-of-global-total-refugees-asylum/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- IDMC. IDMC Mid-Year Figures: Internal Displacement in 2018—World|ReliefWeb. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/idmc-mid-year-figures-internal-displacement-2018 (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Nisbet, C.; Lestrat, K.E.; Vatanparast, H. Food Security Interventions among Refugees around the Globe: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIA. Country Summary. The World Factbook; CIA: Langley, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Putman, D.B.; Noor, M.C. The Somalis: Their History and Culture; CAL Refugee Fact Sheet Series, No. 9; The Refugee Service Center for Applied Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Menkhaus, K. Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project: Somalia Case Study; DFID Stabilisation Unit: East Kilbride, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bakonyi, J.; Chonka, P.; Stuvøy, K. War and City-Making in Somalia: Property, Power and Disposable Lives. Political Geogr. 2019, 73, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakonyi, J. The Political Economy of Displacement: Rent Seeking, Dispossessions and Precarious Mobility in Somali Cities. Glob. Policy 2021, 12, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, A. Displacement in Contested Places: Governance, Movement and Settlement in the Somali Territories. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2013, 7, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruri, M.; Bennison, L.; Kirubi, S.; Galli, A. Multi-Stakeholder Approach to Urban Displacement in Somalia. Forced Migr. Rev. 2020, 63, 19–22. Available online: https://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/cities/cities.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Thalheimer, L.; Schwarz, M.P.; Pretis, F. Large Weather and Conflict Effects on Internal Displacement in Somalia with Little Evidence of Feedback onto Conflict. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2023, 79, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.; Fitzpatrick, M. The 2011 Somalia Famine: Context, Causes, and Complications. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Food Security: Definition and Measurement. Food Sec. 2009, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- IDMC. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/annual-report-2019 (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Kagwanja, P. Blaming the Environment: Ethnic Violence and the Political Economy of Displacement in Kenya; Moi University, Centre for Refugee Studies: Cheptiret, Kenya, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, J. Forced Displacement in Africa: Dimensions, Difficulties, And Policy Directions. Refug. Surv. Q. 2010, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, L. Human Rights Watch Report 2013 Somalia—Search. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?EID=MBHSN&FORM=BWGCDF&PC=W091&q=Human+Rights+Watch+Report+2013+Somalia (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Hammond, L. Somali Refugee Displacements in the Near Region: Analysis and Recommendations; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, J.; Grävingholt, J.; Ziaja, S. Foreign Aid and the Fragile Consensus on State Fragility. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 2015, 18, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, S.D.; Risse, T. External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction. Governance 2014, 27, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risse, T. Governance without a State?: Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-231-52187-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schäferhoff, M. External Actors and the Provision of Public Health Services in Somalia. Governance 2014, 27, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanock, A.M. Governance Delegation Agreements: Shared Sovereignty as a Substitute for Limited Statehood. Governance 2014, 27, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adserà, A.; Boix, C.; Guzi, M.; Pytliková, M. Political Factors as Drivers of International Migration. In Proceedings of the European Population Conference, Mainz, Germany, 31 August–3 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Laws of Migration. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1889, 52, 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, D.B. EG Ravenstein and the “Laws of Migration”. J. Hist. Geogr. 1977, 3, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, F. Aid in a City at War: The Case of Mogadishu, Somalia. Disasters 2012, 36, S105–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasuge, M.; Barnes, C.; Kiepe, T. Land Matters in Mogadishu: Settlement, Ownership and Displacement in a Contested City; Rift Valley Institute: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mukahhal, W.; Abebe, G.; Bahn, R.; Martiniello, G. Historical Construction of Local Food System Transformations in Lebanon: Implications for the Local Food System. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 870412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besteman, C. Representing Violence and “Othering” Somalia. Cult. Anthropol. 1996, 11, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, A. Class and Power in a Stateless Somalia; Social Science Research Council: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, M.H. The Plight of the Agro-pastoral Society of Somalia. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 1996, 23, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsios, A.S. Humanitarian Relief Interventions in Somalia: The Economics of Chaos. Int. Peacekeeping 1996, 3, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, A.; Haslie, A. Unlocking Protracted Displacement; Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cassanelli, L. Refworld | Hosts and Guests: A Historical Interpretation of Land Conflicts in Southern and Central Somalia; Rift Valley Institute (RVI): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cassanelli, L.V. Victims and Vulnerable Groups in Southern Somalia; Research Directorate, Documentation, Information and Research Branch: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Drumtra, J. Internal Displacement in Somalia, Brooking-LSE Project on internal displacement. Brookings Institution, Washington, 2014. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Brookings-IDP-Study-Somalia-December-2014.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Chau, D.C. Linda Nchi from the Sky? Kenyan Air Counterinsurgency Operations in Somalia. Comp. Strategy 2018, 37, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundel, J. The Migration–Development Nexus: Somalia Case Study. Int. Migr. 2002, 40, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwanga-Ntale, C.; Owino, B.O. Understanding Vulnerability and Resilience in Somalia. Jamba 2020, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, N.; McDowell, S. Hidden Dimensions of the Somalia Famine. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Zimmerman, L.; Checchi, F. Internal and External Displacement among Populations of Southern and Central Somalia Affected by Severe Food Insecurity and Famine during 2010–2012; FEWS NET: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elmi, A.A.; Barise, A. The Somali Conflict: Root Causes, Obstacles, and Peace-Building Strategies. Afr. Secur. Rev. 2006, 15, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, I.; Hussein, A.; Lind, J. Deegaan, Politics and War in Somalia; Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies: Pathumthani, Thailand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gundel, J. Clans in Somalia. Austrian Red Cross, Vienna. 2009. Available online: http://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/90_1261130976_accord-report-clans-in-somalia-revised-edition-20091215.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2012).

- Luling, V. Genealogy as Theory, Genealogy as Tool: Aspects of Somali ‘Clanship’. Soc. Identities 2006, 12, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W. Shifting Borders: Africa’s Displacement Crisis and Its Security Implications; Africa Center for Strategic Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S.; Catley, A.; Sheik, H. Livestock and Livelihoods In Protracted Crisis: The Case of Southern Somalia. eLief 2008, 127, 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bryld, E.; Kamau, C.; Sinigallia, D. Analysis of Displacement in Somalia; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Mutavi, T.; Mburu, J.M.; Mathai, M. Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression among Internally Displaced Persons in Mogadishu-Somalia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musisi, S.; Kinyanda, E. Long-Term Impact of War, Civil War, and Persecution in Civilian Populations—Conflict and Post-Traumatic Stress in African Communities. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, J.C.; Eyerman, R.; Giesen, B.; Smelser, N.J.; Sztompka, P. Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity; Univ. of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fanning, E. Drought, Displacement and Livelihoods in Somalia/Somaliland: Time for Gender-Sensitive and Protection-Focused Approaches; Concern Worldwide: Dublin, Ireland, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78748-284-5. [Google Scholar]

- Le Sage, A.; Majid, N. The Livelihoods Gap: Responding to the Economic Dynamics of Vulnerability in Somalia. Disasters 2002, 26, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, K. Livelihoods in Conflict: The Pursuit of Livelihoods by Refugees and the Impact on the Human Security of Host Communities. Int. Migr. 2002, 40, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via Campesina Food Sovereignty | Explained. Available online: https://viacampesina.org/en/food-sovereignty/ (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Patel, R. Food Sovereignty. J. Peasant. Stud. 2009, 36, 663–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Groups (FG) | Characteristics | Age Category (Year) | Livelihood Activities | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG1 to 3 | Community elders | 55 to 70 | Farmers before displaced, currently unemployed | No formal education |

| FG4 to 5 | Men, household heads | 35 to 55 | Most were farmers before displaced but currently work as porters, construction workers, and petty traders | No formal education |

| FG6 to 8 | Women | 30 to 55 | Most engaged in manual labor and petty trading | No formal education |

| FG9 to 10 | Youth | 20 to 30 | Some do manual labor; some go to schools, and some are unemployed | Some with no formal education and others with some primary level education |

| FGD Questions | FGD Response Summary |

|---|---|

| What is your major source of livelihood? |

|

| How has displacement affected your livelihood activities so far? |

|

| What are your current livelihood activities? |

|

| What are the main of the causes of your displacement? |

|

| How did you use your land before displacement? |

|

| How did you cope after displacement/what were your coping mechanisms? |

|

| Why did you seek shelter in alternative areas or camps as IDPs? |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osman, A.A.; Abebe, G.K. Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071444

Osman AA, Abebe GK. Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia. Agriculture. 2023; 13(7):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071444

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsman, Alinor Abdi, and Gumataw Kifle Abebe. 2023. "Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia" Agriculture 13, no. 7: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071444

APA StyleOsman, A. A., & Abebe, G. K. (2023). Rural Displacement and Its Implications on Livelihoods and Food Insecurity: The Case of Inter-Riverine Communities in Somalia. Agriculture, 13(7), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13071444