Evaluating Maturity Index IAD for Storability Potential in Mid-Season and Late-Season Apple Cultivars in the Light of Climate Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Cultivar | Indicator | Observed Effect | Conditions | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Golden Delicious’ | Onset dates of phenology stages | Significant linear relationships between higher air temperature and earlier onset dates | Higher air temperature | [7] |

| No specific | Risk of frost damage | Frequency of relatively rare frost events after blossom | Higher air temperature | [8] |

| No specific | Fungal fruiting date and frequency | First fungal fruiting date is earlier, last fruiting date is later. Increased frequency of reproduction twice per year | Increase in late summer temperatures and autumnal rains | [9] |

| ‘Fuji’, ‘Tsugaru’ | Quality attributes | Decreases in fruit firmness and acid concentration. Some cases of higher soluble solids concentration | Higher air temperatures | [10] |

| ‘Cox’ Orange Pippin’, ‘Granny Smith’ | Chlorophyll concentration in apple skin | Higher temperatures up to ca 25 °C gave faster chlorophyll degradation, but above ca 30 °C the rate went down. | Higher air temperatures | [36] |

| ‘Gala’, ‘Fuji’ | Red skin color | More red skin area in cooler sites than in warmer | Air temperatures | [37] |

| ‘Galaxy’, ‘Cripps Pink’, ‘Braeburn’ | Red skin color | More red skin area in cooler sites than in warmer | Air temperatures | [38] |

| ‘Mondial Gala’ | Anthocyanin concentration Gene expression | Higher anthocyanin concentration in a cooler climatic area than in a warmer. Changes in gene expression | Air temperatures above 20 °C | [39] |

| ‘Iwai’, ‘Sansa’, ‘Tsugaru’, ‘Homei-Tsugaru’, ‘Akane’ | Anthocyanin accumulation Gene expression | Higher anthocyanin concentrations and increase in gene expression at low temperatures | Air temperatures | [40] |

| Various cv. | Firmness | Higher temperatures led to lower firmness in some cultivars but not for all | Higher air temperatures | [37,38] |

| ‘Delicious’, ‘Northern Spy’, ‘Macintosh’ | Starch degradation | Low temperatures favored the conversion of starch to sugar, and high temperatures the reverse | Higher air temperatures | [41] |

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

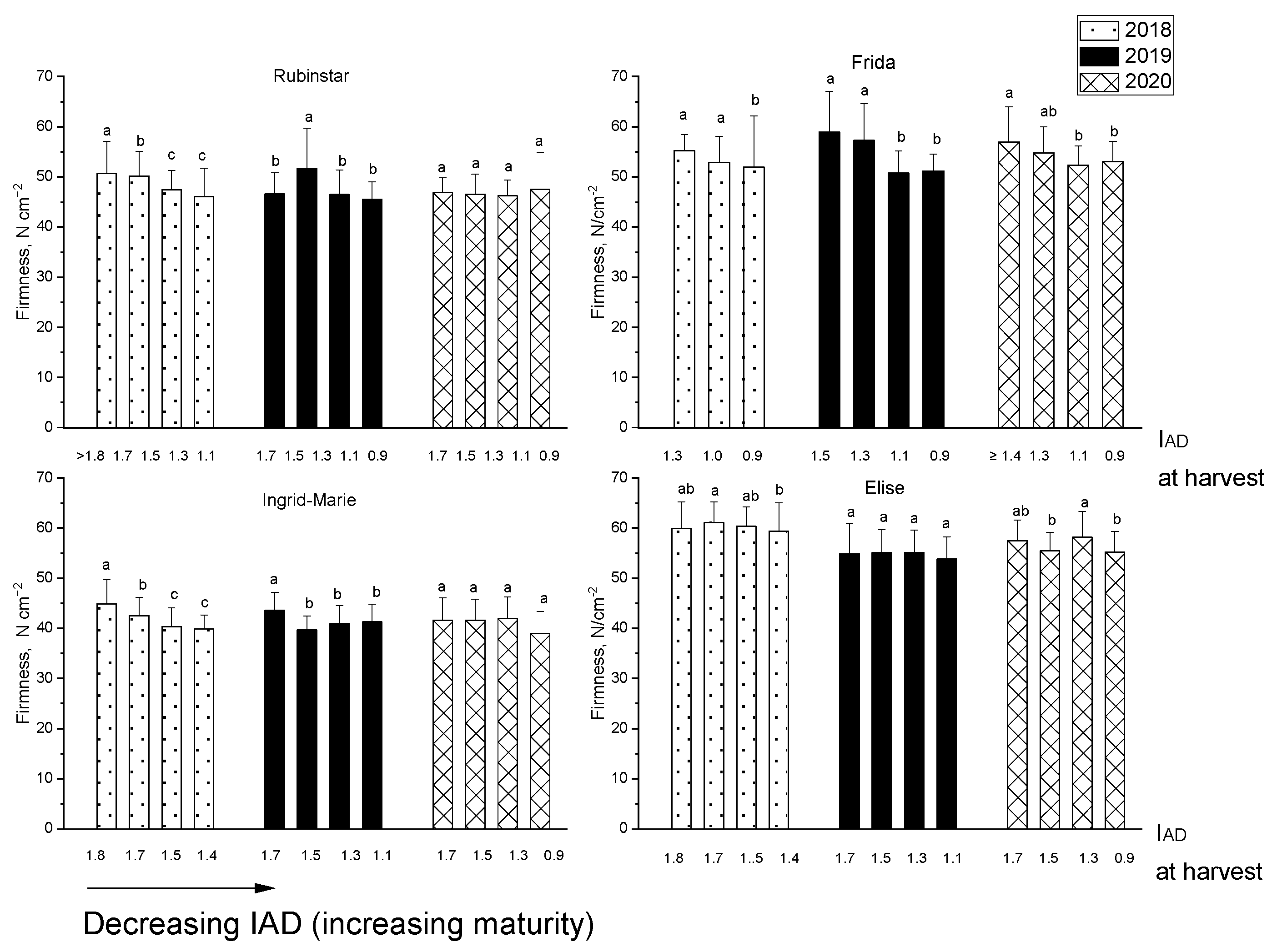

3.1. IAD and Firmness at Harvest Related to Other Parameters After Storage

3.2. Correlations Between IAD and Other Maturity Indices and Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IAD | Index of adsorption difference |

References

- Scialabba, N. FAO, Poster at Conference UNFCCC COP. 2015. Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7fffcaf9-91b2-4b7b-bceb-3712c8cb34e6/content (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture—Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Ao, X. Impacts of Global Climate Change on Agricultural Production: A Comprehensive Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, T.A.; Seixas, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Jägermeyr, J. Severity of drought and heatwave crop losses tripled over the last five decades in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 065012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Offermann, F.; Söder, M.; Frühauf, C.; Finger, R. Extreme weather events cause significant crop yield losses at the farm level in German agriculture. Food Policy 2022, 112, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitu, E.; Paltineanu, C. Timing of phenological stages for apple and pear trees under climate change in a temperate-continental climate. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfleiderer, P.; Menke, I.; Schleussner, C.F. Increasing risks of apple tree frost damage under climate change. Clim. Change 2019, 157, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gange, A.C.; Gange, E.G.; Sparks, T.H.; Boddy, L. Rapid and Recent Changes in Fungal Fruiting Patterns. Science 2007, 316, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, T.; Ogawa, H.; Fukuda, N.; Moriguchi, T.X. Changes in the taste and textural attributes of apples in response to climate change. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, D. World production, trade, consumption and economic outlook for apples. In Apples: Botany, Production and Uses; Ferree, D.C., Warrington, I.J., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassénius, E.; Porkka, M.; Nyström, M.; Jørgensen, P.S. A global analysis of potential self-sufficiency and diversity displays diverse supply risks. Glob. Food Secur. 2023, 37, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E. Quantitative study of ethylene production in apple varieties. Plant Physiol. 1945, 20, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.B. Ethylene synthesis, mode of action, consequences and control. In Fruit Quality and Its Biological Basis; Knee, M., Ed.; Sheffield Academic Press Ltd.: Sheffield, UK, 2002; pp. 180–224. [Google Scholar]

- Nybom, H.; Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Sehic, J.; Hertog, M. DNA marker-assisted evaluation of fruit firmness at harvest and post-harvest fruit softening in a diverse apple germplasm. Tree Genet. Genomes 2012, 9, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.W.; Hewett, E.W.; Hertog, M.L.A.T.M. Postharvest softening of apple (Malus domestica) fruit: A review. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2002, 30, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homutová, I.; Blažek, J. Differences in fruit skin thickness between selected apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) cultivars assessed by histological and sensory methods. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 33, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leide, J.; de Souza, A.X.; Papp, I.; Riederer, M. Specific characteristics of the apple fruit cuticle: Investigation of early and late season cultivars ‘Prima’ and ‘Florina’ (Malus domestica Borkh.). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Tahir, I.; Nybom, H. Impact of harvesting time and fruit firmness on the tolerance to fungal storage diseases in an apple germplasm collection. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prange, R.; DeLong, J.; Nichols, D.; Harrison, P. Effect of fruit maturity on the incidence of bitter pit, senescent breakdown, and other post-harvest disorders in ‘Honeycrisp’(TM) apple. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 86, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstrand, J.; Tahir, I.; Hovmalm, H.P.; Stridh, H.; Olsson, M.E. Multiple factors affecting occurrence of soft scald and fungal decay in apple during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 201, 112344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.B.; Erkan, M.; Nock, J.E.; Iungerman, K.A.; Beaudry, R.M.; Moran, R.E. Harvest date effects on maturity, quality, and storage disorders of ‘Honeycrisp’ apples. HortScience 2005, 40, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millerd, A.; Bonner, J.; Biale, J.B. The climacteric rise in fruit respiration as controlled by phosphorylative coupling. Plant Physiol. 1953, 28, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirs, A.; Lammertyn, J.; Ooms, K.; Nicolai, B.M. Prediction of the optimal picking date of different apple cultivars by means of VIS/NIR-spectroscopy. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2001, 21, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, S.M.; Parker, M.; Unrath, C.R. Use of maturity indices for predicting poststorage firmness of ‘Fuji’ apples. HortScience 1997, 32, 909–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannok, P.; Kamitani, Y.; Kawano, S. Development of a common calibration model for determining the Brix value of intact apple, pear and persimmon fruits by near infrared spectroscopy. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2014, 22, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Padfield, C.; Watkins, C.; Harman, J. Starch iodine pattern as a maturity index for Granny Smith apples: 1. Comparison with flesh firmness and soluble solids content. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 1982, 25, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streif, J. Optimum harvest date for different apple cultivar in the ‘Bodensee’ area. In Proceedings of the Working Group on Optimum Harvest Date COST 94, Lofthus, Norway, 9–10 June 1996; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong, J.; Prange, R.; Harrison, P.; Nichols, D.; Wright, H. Determination of optimal harvest boundaries for Honeycrisp (TM) fruit using a new chlorophyll meter. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasordzi, J.; Friedman, H.; Schmilovitch, Z.; Ignat, T.; Weksler, A.; Rot, I.; Lurie, S. Utilizing the IAD index to determine internal quality attributes of apples at harvest and after storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 77, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, J.M.; Harrison, P.A.; Harkness, L. Determination of optimal harvest boundaries for ‘Ambrosia’ apple fruit using a delta-absorbance meter. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lecourt, J.; Bishop, G. Advances in Non-Destructive Early Assessment of Fruit Ripeness towards Defining Optimal Time of Harvest and Yield Prediction—A Review. Plants 2018, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, C.; Yang, H.; Jiang, H.; Li, L.; Yang, G. Non-destructive and in-site estimation of apple quality and maturity by hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 195, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötze, E.; Bergh, O. Evaluating the Streif index against commercial subjective predictions to determine the harvest date of apples in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2012, 29, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Jacob, S.; Siddiqui, M.W. Chapter 2-Fruit Maturity, Harvesting, and Quality Standards. In Preharvest Modulation of Postharvest Fruit and Vegetable Quality; Siddiqui, M.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Hewett, E. Temperature affects postharvest change of apples. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1998, 123, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenta, L.C.; do Amarante, C.V.T.; de Freitas, S.T.; Brancher, T.L.; Nesi, C.N.; Mattheis, J.P. Fruit quality of ‘Gala’ and ‘Fuji’ apples cultivated under different environmental conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuri, J.A.; Moggia, C.; Sepulveda, A.; Poblete-Echeverría, C.; Valdés-Gómez, H.; Torres, C.A. Effect of cultivar, rootstock, and growing conditions on fruit maturity and postharvest quality as part of a six-year apple trial in Chile. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 253, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Wang, K.U.I.; Micheletti, D.; Palmer, J.; Volz, R.; Lozano, L.; Espley, R.; Allan, A.C. High temperature reduces apple fruit colour via modulation of the anthocyanin regulatory complex. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 34, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubi, B.E.; Honda, C.; Bessho, H.; Kondo, S.; Wada, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Moriguchi, T. Expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in apple skin: Effect of UV-B and temperature. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.B.; Lougheed, E.C.; Franklin, E.W.; McMillan, I. The starch iodine test for determining stage of maturation in apples. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1979, 59, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; Vangdal, E. Determination of optimum harvest maturity for five apple cultivars using the chlorophyll absorbance index. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1261, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-C.; Park, Y.-S.; Jeong, H.-N.; Kim, J.-H.; Heo, J.-Y. Temperature Changes Affected Spring Phenology and Fruit Quality of Apples Grown in High-Latitude Region of South Korea. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxin, P.; Weber, R.W.S.; Pedersen, H.L.; Williams, M. Control of a wide range of storage rots in naturally infected apples by hot-water dipping and rinsing. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 70, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I. What spoils Swedish apples during storage? Acta Hortic. 2019, 1256, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiuskaite, A.; Kvikliene, N.; Kviklys, D.; Lanauskas, J. Post-harvest fruit rot incidence depending on apple maturity. Agron. Res. 2006, 4, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Di Francesco, A.; Placì, N.; Scialanga, B.; Ceredi, G.; Baraldi, E. Ripe indexes, hot water treatments, and biocontrol agents as synergistic combination to control apple bull’s eye rot. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, I.L.; Vangdal, E.; Børve, J. Effect of Different Maturity (Measured as IAD Index) on Storability of Apples in CA-Bags. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1071, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel, S.; Meinshausen, N.; Fischer, E.M.; Székely, E.; Knutti, R. Climate change now detectable from any single day of weather at global scale. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO (World Metrological Organization). State of the Global Climate 2023, WMO-No 1347. ISBN 978-92-63-11347-4. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/68835-state-of-the-global-climate-2023 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Sjöstrand, J.; Tahir, I.; Persson Hovmalm, H.; Garkava-Gustavsson, L.; Stridh, H.; Olsson, M.E. Comparison between IAD and other maturity indices in nine commercially grown apple cultivars. Sci. Horticult. 2024, 324, 112559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMHI (The Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute). Skånes klimat. Available online: https://www.smhi.se/kunskapsbanken/klimat/klimatet-i-sveriges-landskap/skanes-klimat (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Houston, L.; Capalbo, S.; Seavert, C.; Dalton, M.; Bryla, D.; Sagili, R. Specialty fruit production in the Pacific Northwest: Adaptation strategies for a changing climate. Clim. Change 2018, 146, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotelli, D.; Montagnani, L.; Andreotti, C.; Tagliavini, M. Water and carbon fluxes in an apple orchard during heat waves. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 134, 126460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vielma, M.S.; Matta, F.B.; Silval, J.L. Optimal harvest time of various apple cultivars grown in Northern Mississippi. J. Am. Pomol. Soc. 2008, 62, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Børve, J.; Røen, D.; Stensvand, A. Harvest Time Influences Incidence of Storage Diseases and Fruit Quality in Organically Grown ‘Aroma’ Apples. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 78, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andani, Z.; Jaeger, S.R.; Wakeling, I.; MacFie, H.J.H. Mealiness in Apples: Towards a Multilingual Consumer Vocabulary. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, F.R.; Kupferman, E.M.; Marin, A.B.; Gunson, F.A.; Triggs, C.M. Eating quality standards for apples based on consumer preferences. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 50, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadar, N.; Zanella, A. A Study on the Potential of IAD as a Surrogate Index of Quality and Storability in cv. ‘Gala’ Apple Fruit. Agron. 2019, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.W.; Gunaseelan, K.; Pidakala, P.; Wang, M.; Schaffer, R.J. Co-ordination of early and late ripening events in apples is regulated through differential sensitivities to ethylene. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2689–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitt, B.D.; McCartney, H.; Walklate, P. The role of rain in dispersal of pathogen inoculum. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1989, 27, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Cholodowski, D.; Bompeix, G. Adhesion and germination of waterborne and airborne conidia of Penicillium expansum to apple and inert surfaces. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 67, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Ehret, G.; Meyer, M.; Shane, W. Occurrence of bitter rot on apple in Michigan. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golias, J.; Mylova, P.; Nemcova, A. A comparison of apple cultivars regarding ethylene production and physico-chemical changes during cold storage. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 35, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Lee, J.; Kwon, S.I.; Chung, K.H.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, I.M.; Kang, I.K. Differences in ethylene and fruit quality attributes during storage in new apple cultivars. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2016, 34, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagné, D.; Dayatilake, D.; Diack, R.; Oliver, M.; Ireland, H.; Watson, A.; Tustin, S. Genetic and environmental control of fruit maturation, dry matter and firmness in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Hortic. Res. 2014, 1, 14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migicovsky, Z.; Yeats, T.H.; Watts, S.; Song, J.; Forney, C.F.; Burgher-MacLellan, K.; Somers, D.J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Vrebalov, J.; et al. Apple Ripening Is Controlled by a NAC Transcription Factor. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 671300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Year | Harvest | SSC °Brix | Respiration, | Ethylene Production, | Physiological Disorders, % | Fungal Decay, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAD | vol% h−1 | ppm h−1 | |||||

| Frida | 2018 | 1.27 | 13.18 ± 0.96 a | N/A | N/A | 6.6 | 0 |

| 0.99 | 13.41 ± 0.93 a | N/A | N/A | 8.3 | 0.8 | ||

| 0.89 | 13.54 ± 0.78 a | N/A | N/A | 2.5 | 0 | ||

| 2019 | 1.4–1.6 | 12.34 ± 1.48 b | 0.13 ± 0.05 b | 6.16 ± 2.04 c | 1.7 | 0 | |

| 1.2–1.4 | 12.39 ± 1.04 b | 0.14 ± 0.02 b | 6.79 ± 1.06 bc | 1.7 | 3.3 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 12.74 ± 0.94 ab | 0.18 ± 0.05 a | 8.27 ± 1.72 b | 0.8 | 3.3 | ||

| 0.8–1.0 | 12.99 ± 0.84 a | 0.18 ± 0.06 a | 7.24 ± 1.85 b | 3.3 | 0.8 | ||

| 2020 | 1.4–1.7 | 12.44 ± 1.04 b | 0.17 ± 0.03 b | 8.54 ± 1.69 a | 0 | 0 | |

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.08 ± 0.84 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 a | 8.30 ± 2.11 a | 4.2 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 12.74 ± 0.80 ab | 0.18 ± 0.03 ab | 8.35 ± 1.60 a | 8.3 | 0 | ||

| 0.8–1.0 | 12.72 ± 0.65 ab | 0.19 ± 0.06 ab | 8.52 ± 4.32 a | 4.2 | 0 | ||

| Ingrid Marie | 2018 | 1.5–2.0 | 14.05 ± 1.19 a | N/A | N/A | 2.5 | 9.2 |

| 1.5–1.8 | 13.22 ± 1.03 b | N/A | N/A | 0 | 5.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 14.43 ± 1.05 a | N/A | N/A | 2.5 | 19.2 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.98 ± 0.70 a | N/A | N/A | 0.8 | 15.8 | ||

| 2019 | 1.6–1.8 | 12.95 ± 1.27 a | 0.15 ± 0.03 b | 6.97 ± 1.43 b | 0 | 1.7 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 13.13 ± 1.04 a | 0.19 ± 0.06 a | 7.46 ± 2.17 b | 0 | 2.5 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.07 ± 1.22 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 a | 11.33 ± 4.40 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.46 ± 1.07 a | 0.22 ± 0.12 a | 9.99 ± 5.46 a | 0 | 9.2 | ||

| 2020 | 1.6–1.8 | 13.41 ± 1.30 a | 0.18 ± 0.04 c | 7.86 ± 1.68 b | 0 | 4.2 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 13.81 ± 1.00 a | 0.29 ± 0.08 ab | 10.62 ± 4.90 a | 0 | 4.2 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.96 ± 1.24 a | 0.30 ± 0.05 a | 11.89 ± 4.70 a | 1.7 | 14.2 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.40 ± 1.34 a | 0.26 ± 0.07 b | 9.81 ± 3.14 a | 0 | 8.3 |

| Cultivar | Year | Harvest | SSC °Brix | Respiration, | Ethylene Production, | Phys. Disorders, % | Fungal Decay, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAD | vol% h−1 | ppm h−1 | |||||

| Rubinstar | 2018 | >1.8 | 14.30 ± 0.90 a | N/A | N/A | 0.8 | 3.3 |

| 1.6–1.8 | 13.99 ± 0.94 a | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1.7 | ||

| 1.4–1.6 | 13.28 ± 1.05 b | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.31 ± 0.78 b | N/A | N/A | 11.7 | 0 | ||

| 2019 | 1.6–1.8 | 12.72 ± 0.90 b | 0.14 ± 0.06 b | 10.01 ± 3.83 b | 0 | 0.8 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 14.00 ± 1.16 a | 0.22 ± 0.08 a | 12.63 ± 6.45 b | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 12.81 ± 1.01 b | 0.20 ± 0.07 a | 13.01 ± 5.81 b | 0 | 1.7 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.05 ± 0.65 b | 0.21 ± 0.09 a | 20.28 ± 10.73 a | 0.8 | 0 | ||

| 2020 | 1.6–1.8 | 13.00 ± 0.77 b | 0.17 ± 0.04 c | 11.15 ± 3.64 a | 0 | 0 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 12.63 ± 1.60 b | 0.22 ± 0.04 a | 11.44 ± 2.07 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.60 ± 0.75 a | 0.19 ± 0.04 b | 11.60 ± 3.79 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.93 ± 1.18 a | 0.20 ± 0.06 b | 11.24 ± 3.2 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| Elise | 2018 | 1.72 | 13.14 ± 0.83 a | N/A | N/A | 0.8 | 0 |

| 1.74 | 12.96 ± 1.19 a | N/A | N/A | 0 | 2.5 | ||

| 1.53 | 13.02 ± 1.34 a | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.43 | 12.70 ± 1.47 a | N/A | N/A | 1.7 | 0.8 | ||

| 2019 | 1.6–1.8 | 11.90 ± 1.10 c | 0.15 ± 0.04 a | 3.40 ± 0.74 b | 0 | 2.5 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 12.16 ± 1.25 bc | 0.17 ± 0.05 a | 4.51 ± 1.20 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 12.57 ± 0.92 ab | 0.12 ± 0.04 b | 3.71 ± 1.06 b | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.11 ± 1.37 a | 0.15 ± 0.03 a | 3.96 ± 0.89 ab | 0 | 1.7 | ||

| 2020 | 1.6–1.8 | 11.83 ± 1.02 c | 0.17 ± 0.05 b | 5.20 ± 2.53 ab | 0 | 0.8 | |

| 1.4–1.6 | 12.60 ± 1.46 b | 0.18 ± 0.03 b | 5.71 ± 3.25 a | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.2–1.4 | 13.69 ± 1.62 a | 0.18 ± 0.04 ab | 3.51 ± 1.12 c | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| 1.0–1.2 | 13.33 ± 1.27 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 a | 4.49 ± 1.13 bc | 0 | 2.5 |

| Cultivar | Year | Respiration | Ethylene | Firmness | Soluble Solids | Total Losses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Conc. | |||||

| Frida | 2018 | N/A | N/A | ns | −0.154 * | 0.248 *** |

| 2019 | −0.320 *** | −0.170* | 0.479 *** | −0.159 * | −0.168 * | |

| 2020 | −0.285 *** | ns | 0.273 *** | −0.181 ** | −0.455 *** | |

| Ingrid Marie | 2018 | N/A | N/A | 0.412 *** | −0.135 * | −0.372 *** |

| 2019 | −0.222 ** | −0.363 *** | 0.151* | −0.142 * | −0.540 *** | |

| 2020 | −0.386 *** | −0.210 ** | ns | ns | −0.592 *** | |

| Rubinstar | 2018 | N/A | N/A | 0.426 *** | 0.398 *** | −0.699 *** |

| 2019 | −0.394 *** | −0.386 *** | ns | ns | −0.215 ** | |

| 2020 | ns | ns | ns | −0.405 *** | −0.302 *** | |

| Elise | 2018 | N/A | N/A | ns | ns | −0.267 *** |

| 2019 | ns | ns | ns | −0.362 *** | −0.280 *** | |

| 2020 | −0.321 *** | 0.208 * | ns | −0.401 *** | −0.665 *** |

| Cultivar | Year | Daily Min. Temp. °C | Daily Aver. Temp. °C | No Days Max. Temp. ≥ 25 °C | Relative Humidity % | Rainfall (Total) L/m2 | Solar Radiation MJ/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frida | 2018 | 12.78 | 17.58 | 38 | 79.62 | 188 | 23.44 |

| 2019 | 12.50 | 16.15 | 7 | 87.91 | 398 | 16.51 | |

| 2020 | 13.21 | 15.67 | 13 | 81.00 | 175 | 20.75 | |

| Ingrid Marie | 2018 | 12.30 | 18.84 | 52 | 71.46 | 125 | 29.62 |

| 2019 | 11.75 | 16.10 | 26 | 81.7 | 326 | 21.41 | |

| 2020 | 11.12 | 15.91 | 21 | 77.03 | 160 | 20.91 | |

| Rubinstar | 2018 | 12.78 | 17.58 | 52 | 79.62 | 188 | 23.44 |

| 2019 | 11.32 | 15.59 | 26 | 82.08 | 335 | 20.70 | |

| 2020 | 11.45 | 15.57 | 21 | 81.54 | 192 | 20.17 | |

| Elise | 2018 | 11.47 | 17.58 | 38 | 79.62 | 188 | 23.44 |

| 2019 | 11.89 | 15.29 | 7 | 86.21 | 398 | 19.22 | |

| 2020 | 11.47 | 15.59 | 13 | 81.45 | 187 | 20.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sjöstrand, J.; Tahir, I.; Stridh, H.; Olsson, M.E. Evaluating Maturity Index IAD for Storability Potential in Mid-Season and Late-Season Apple Cultivars in the Light of Climate Change. Agriculture 2025, 15, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080889

Sjöstrand J, Tahir I, Stridh H, Olsson ME. Evaluating Maturity Index IAD for Storability Potential in Mid-Season and Late-Season Apple Cultivars in the Light of Climate Change. Agriculture. 2025; 15(8):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080889

Chicago/Turabian StyleSjöstrand, Joakim, Ibrahim Tahir, Henrik Stridh, and Marie E. Olsson. 2025. "Evaluating Maturity Index IAD for Storability Potential in Mid-Season and Late-Season Apple Cultivars in the Light of Climate Change" Agriculture 15, no. 8: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080889

APA StyleSjöstrand, J., Tahir, I., Stridh, H., & Olsson, M. E. (2025). Evaluating Maturity Index IAD for Storability Potential in Mid-Season and Late-Season Apple Cultivars in the Light of Climate Change. Agriculture, 15(8), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080889