2. The Initial Establishment of the Relation between Buddhist Monasteries and the Political Axis of Capitals

The clarion call for Buddhist monasteries to march on the political axis was sounded during the Northern Wei period (386–534). After the capital, Pingcheng (nowadays Datong), was established in the early Northern Wei, the relation between Buddhism and imperial power entered a new stage. The rulers of Northern Wei first developed the political philosophical concept that “the emperor is the Buddha,” which firmly tied politics and religion together (

Luo 2021, p. 244). The rulers built large Buddhist monasteries (pagodas), recruited monks, and built grottoes (such as Tanyao Five Caves in Yungang Grottos) in Pingcheng in the name of the imperial family, and brought Buddhism under the supervision of political power. Different from the White Horse Monastery outside Luoyang of the Eastern Han and the 42 monasteries in Luoyang during the Yongjia period (307–311) of the Western Jin, the pagodas and Buddhist monasteries in Pingcheng had become an organic component of the capital landscape.

When Emperor Daowu (371–409, r. 386–409) established the capital in Pingcheng, he “started to make the five-story Buddha pagoda, the Grdhrakūta Mountain and the Hall of Miru Mountain, and decorated them. Additionally, he built lecture halls, meditation halls and seats of monks. These things were prepared very well” (

Wei 2017, p. 3292). During the reign of Emperor Taiwu (408–452, r. 424–451), Buddhism in Northern Wei was severely destroyed, but it did not totally fail. After Emperor Xianwen (454–476, r. 465–471) ascended to the throne in the sixth year of the Heping period (465), he re-supported Buddhism, and successively established important Buddhist buildings such as Yongning Monastery, Tiangong Monastery, and the three-story stone pagoda in Pingcheng (

Wei 2017, p. 3300). Although archaeologists have not yet clarified the specific location of the seven-story Yongning Monastery Pagoda or carried out archaeological excavations on this building, according to the description of existing documents, the height of the pagoda of Yongning Monastery in Pingcheng reached more than 300

chi (if the total length of 1

chi is 27.868 cm, it should be above 83.7 m), totaling seven stories (

Wei 2017, p. 3300). The total height and volume of this multi-story pagoda was a record for this time. It was a civil-wood mixed structure containing a huge core in its center. Archaeological excavations have revealed the location of Siyuan Pagoda in the Yonggu Mausoleum on the mountain in the northeast of Pingcheng (

Datongshi Bowuguan 2007, pp. 4–26). Yet the specific location of the most important Buddhist architectural landscapes in Pingcheng, such as the Yongning Monastery Pagoda, are still unclear and thus the relations between such Buddhist monasteries and pagodas regarding the axis of the capital is also unclear. An exception may be the continued use of the title of Yongning Monastery Pagoda in Luoyang (

Yang 2018, p. 11), the capital of the late period of the Northern Wei (494–534). It is most likely that the distribution of large Buddhist monasteries and pagodas in Pingcheng was no longer in remote suburbs or scattered in the city, but had become an important part of the organic development of the city as a whole.

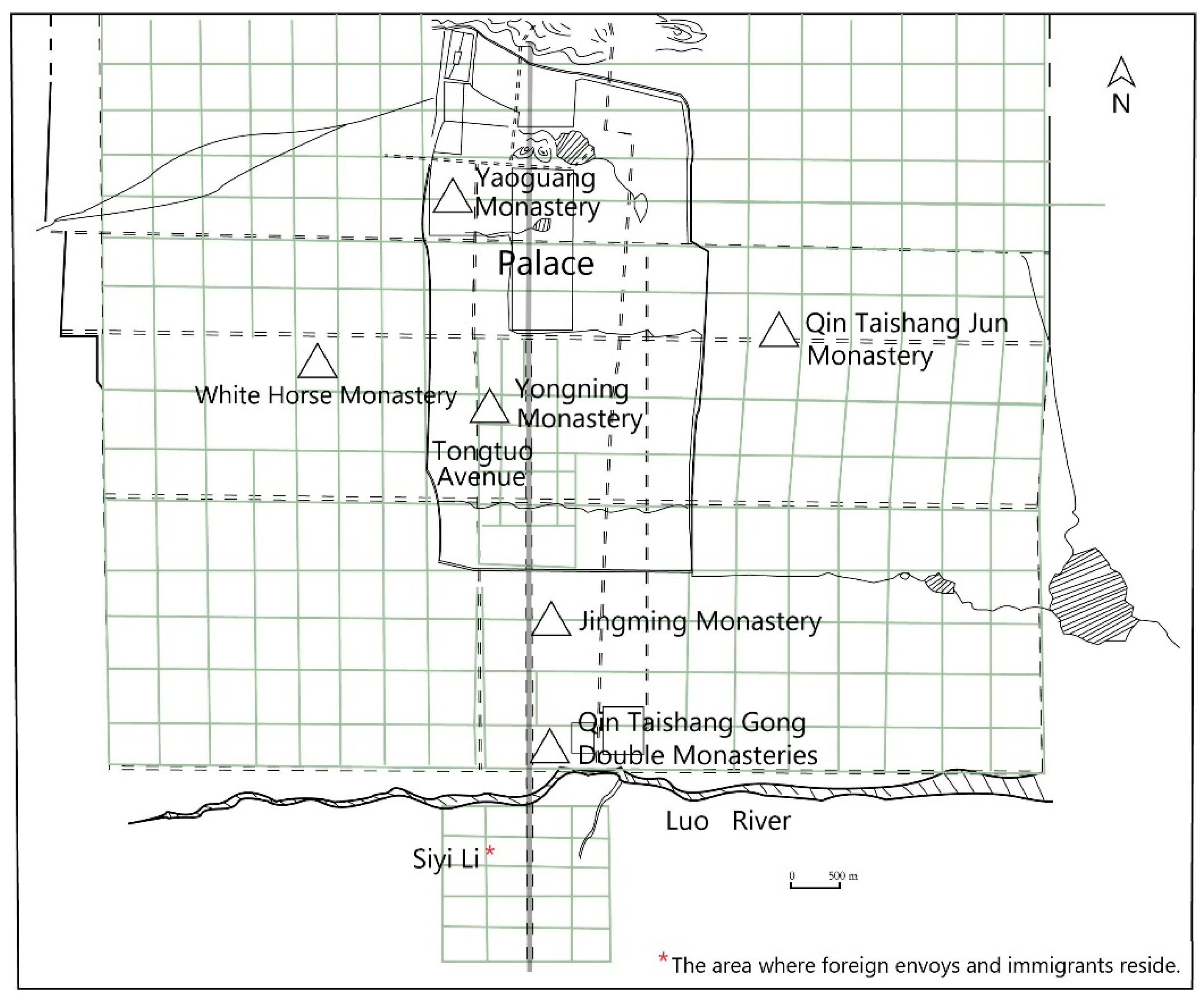

That the locations of Buddhist monasteries, especially the imperial monasteries, were close to the central axis of power in the capital in the late Northern Wei is demonstrated by the arrangement of Yongning Monastery, Jingming Monastery, and Qin Taishang Gong Double Monasteries in Luoyang, flanking the sides of Bronze Camel (

Tongtuo) Avenue, the central axis of power in the capital of the Northern Wei.

1 The five-story double towers of Qin Taishang Gong Monastery, seven-story Jingming Monastery Pagoda, and nine-story Yongning Monastery Pagoda from south to north formed one arithmetically balanced sequence of stories of Buddhist buildings.

2 The arithmetically balanced sequence gradually increased as the distance decreased between these pagodas and Taiji Hall, the center of absolute power. In terms of the south-to-north spatial layout of Luoyang in the Northern Wei, it followed the following distribution: (1)

Siyi Li,

Siyi Fang (the area where foreign envoys and immigrants reside), and the

Sitong Market to the south of the Luo River; (2) a regular block (

Lifang) district, a large area of residents in the south of Xuanyang Gate; (3) the Ancestral Shrine, the Altar of Land and Grain, and the districts of official buildings on both sides of

Tongtuo Street, the axis of the previous city of Han and Jin (the so-called inner city); and (4) the palace in the north part of the inner city. Luoyang in the Northern Wei showed a unidirectional layered tandem structure on the axis from the palace in the north to the Altar of Heaven in the south. With the exception of the Altar of Heaven in the south end of this axis, the distribution unfolded from barbarians to Chinese, from the outside to the inside, and from low status to high status. However, the monasteries established by Buddhism from the Western Regions (

xiyu) were not totally located in

Siyi Fang and

Siyi Li to the south of the Luo River because of their foreign religious status, but were located in the

Lifang district and the official institutes district to the north of the Luo River. In other words, compared to the White Horse Monastery located in the western suburbs of the capital in the Eastern Han, the grand monasteries with imperial backgrounds such as Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery at this time had already approached the inner area of the palace to symbolize the highest imperial power. Yongning Monastery was the only imperial Buddhist monastery in the city that was planned according to the “Capital Planning” of Emperor Xiaowen (467–499, r. 471–499), who moved to Luoyang (

Wei 2017, p. 3306). Jingming Monastery was built by his son, Emperor Xuanwu (483–515, r. 499–515), with a slightly lower status in being located farther away from the palace (

Yang 2018, p. 133). In addition, the Qin Taishang Gong Double Monasteries built by Empress Ling (?–528) and her sister Hu Xuanhui (?–556)

3 for their father, Hu Guozhen (438–518), were located in the south of Jingming Monastery and north of the Luo River, farther away from the palace.

Luoyang’s Buddhist architectural landscape in the late period of the Northern Wei created a new pattern completely different from the Eastern Han, Wei, and Jin periods both in terms of its relation with the political axis and its interaction with the power center. With the construction of remarkably high pagodas and grand imperial monasteries (such as Jingming Monastery and Yongning Monastery) occupying one fang (the standard block in the capital of the Northern Wei) and a half fang on the both sides of the central axis of the capital as new power monuments, the urban landscape of Luoyang had undergone fundamental changes. The importance of Buddhist architecture in the construction of the political landscape of the capital and the display of power had been unprecedentedly strengthened, dwarfing the declining ritual buildings in the southern suburbs.

A detailed evolution of the spatial distribution of Luoyang monasteries in the late Northern Wei Dynasty is provided in four stages, according to the research results of Hu Manli’s M. A. dissertation, “Buddhist Monasteries and Urban Space in Luoyang of Northern Wei (495–534): based on

Luoyang Qielan Ji”

4:

The first stage was from the eighteenth year of the Taihe period of Emperor Xiaowen (494) to the first year of the Zhengshi period of Emperor Xuanwu (504). There were 12 Buddhist monasteries built by the records of

Luoyang Qielan Ji, two in the inner city and two in the east area of the inner city, five in the south area of the inner city, three in the west area of the inner city, and none in the north. There were relatively more Buddhist monasteries built in the south of the city. Yongning Monastery on the west side of the central axis of the Official Institutes District and Jingming Monastery on the east side of the central axis of

Lifang District, located in the south area of the inner city, had been built at this time, but the pagodas of these two monasteries had not yet been built. The three monasteries of Baode, Longhua, and Zhuisheng, built in

Quanxue Li in the south area of the inner city, had approached or even invaded the traditional space of Confucian ritual architecture, reflecting the deep involvement of Buddhist architecture in the political core area of the capital. In terms of pagoda construction, there were three pagodas with three or more stories built in Luoyang at that time by the records in

Luoyang Qielan Ji, one each in the inner city, the east area of the inner city, and the west area of the inner city. The tallest pagoda in Yaoguang Monastery

5 was located to the northwest of the inner city, close to Jinyong Fortresses. Judging from the location of the commanding heights of the capital, according to the information provided by

Shuijing Zhu,

Taiping Yulan,

Henan Zhi, and other documents, the inherent commanding heights of Luoyang in the Han and Jin Dynasties should be located in the Jinyong Fortresses and

Baichilou (a one-hundred-

chi-high pavilion)

6 area, located to the northwest of the inner city. The construction of the five-story pagoda of Yaoguang Monastery at the beginning of Luoyang as the new capital of the Northern Wei did not change this basic pattern. Therefore, in the early years of the reign of Emperor Xuanwu, the grand Buddhist monasteries in the Luoyang of the Northern Wei (such as Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery) had been lined up on the both sides of the political axis. However, because the pagodas of Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery were not built, in the three-dimensional space, the remarkably high pagodas still had not much influence or disturbance on the political and cultural landscape along the central axis of the capital. The progressive city gates and palace gates were still the main buildings of this axis.

The second stage was the ten years from the first year of the Zhengshi period to the third year of the Yanchang period (514), mainly during the reign of Emperor Xuanwu. There was no significant change in the Buddhist landscape near Luoyang’s political axis. Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery were still the remarkable cores of the Buddhist landscape in Luoyang. The commanding height of the city was still the five-story pagoda of Yaoguang Monastery to the south of Jinyong Fortresses and to the northwest of the inner city. Compared with the first ten years after moving the capital to Luoyang, there was no significant transformation. With the development of the outer city area, a series of emerging Buddhist monasteries, such as Pingdeng Monastery, Zhengshi Monastery, Yongming Monastery, and Dajue Monastery, had indeed appeared in the east and west of the city. However, these monasteries were far away from the political axis of Luoyang and did not remarkably disturb it.

The third stage was from the third year of the Yanchang period to the fifth year of the Zhengguang period (524) of Emperor Xiaoming (510–528, r. 515–528), mainly during the reign of Empress Ling. This period was a stage of vigorous development for Buddhist monasteries in Luoyang, and it was also a peak for the construction of high and super-high pagodas. According to my statistics, there were only two large-scale pagodas with nine or seven stories in Luoyang, the new capital of the Northern Wei, all of which were built during the reign of Empress Ling. Among the eight five-story medium-sized pagodas, there were also two pagodas in Qin Taishang Jun Monastery and Qin Taishang Gong West Monastery built by Empress Ling, and Hutong Monastery and Qin Taishang Gong East Monastery were built by her aunt and younger sister. These four monasteries already accounted for 50% of the total number of monasteries with five-story pagodas. If Chongjue Monastery and Rongjue Monastery, which were roughly built in the same period or later, related to Yuan Yi (487–520), were added to this list, then the number of monasteries with five-story pagodas actually accounted for three-quarters of the total at that time. Only the pagoda of Yaoguang Monastery (

Yang 2018, p. 48), built in the time of Emperor Xuanwu, and the five-story pagoda built in Pingdeng Monastery (

Yang 2018, p. 109)

7 after Emperor Xiaowu (Yuan Xiu, 510–535, r. 532–535) ascended the throne, were not established in the period of Empress Ling. Additionally, I prefer not to analyze the three-story pagodas recorded in

Luoyang Qielan Ji because of their small volume and the difficulty in determining their construction date clearly. In summary, most of the large and medium-sized pagodas with more than five stories in Luoyang in the Northern Wei were built during the period of Empress Ling (see

Table 1).

8The distribution of Buddhist monasteries in the two-dimensional space made the east side of the political axis from the north bank of the Luo River to Xuanyang Gate almost entirely occupied by Buddhist monasteries. This area was originally the location of “Three

Yong” buildings (

Lingtai,

Mingtang (The Bright Hall) and

Piyong), traditional Confucian ritual buildings in the southern suburbs during the Eastern Han Dynasty. At that time, the

Lingtai and

Piyong had long been abandoned, and the

Mingtang was rebuilt after the coup by Yuan Cha (

Wei 2017, p. 283). The decline of the ritual architecture area in the southern suburb of the capital at that time was obvious, and could not compete with the architecture of increasingly glorious imperial Buddhist monasteries. Looking north from the south bank of the Luo River, the visual landscape that greeted the viewer was no longer ritual architecture but the magnificent three pagodas of Qin Taishang Gong Double Monasteries and Jingming Monastery in a triangular arrangement (

Xie Forthcoming, p. 24). The latter had become a new visual center in the southern area of the capital and even on both sides of the central city’s political axis.

The fourth stage dated from the fifth year of the Zhengguang period (524) to the third year of the Yongxi period (534), which was the year when Yongning Monastery was burned and of the division of the Eastern and Western Wei. Additionally, it was also the final stage of Luoyang as the capital of the Northern Wei. Monasteries inside and outside the inner city continued to grow, particularly after the massacre in 528, and as more nobles died, tributary monasteries were built. However, the new Wei court seemed unable to build giant, super-high pagodas, such as the pagodas of Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery. Buddhist monasteries were no longer part of a unified city plan (see

Figure 1).

Nonetheless, changes in the number of Buddhist monasteries were minimal. With the division of the Eastern Wei (534–550) and Western Wei (535–556) and the transfer of the capital of the empire to Yecheng and Chang’an in 534, I use Yecheng, the capital of the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi (550–577), to exemplify changes in the dynamics between political expediency and Buddhist influences. In recent years, the site of Zhaopengcheng Buddhist Monastery and Da Zhuangyan Monastery was unearthed by the Yecheng Team of the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The two were located on the east side of Zhuming Gate Avenue along the central axis of Yecheng.

10 The relative position of the Zhaopengcheng Buddhist Monastery was almost exactly the same as that of Jingming Monastery in Luoyang during the Northern Wei. The pagodas of Zhaopengcheng Monastery (Da Zongchi Monastery)

11 and Da Zhuangyan Monastery may have had seven stories, not reaching the height of the nine-story Yongning Monastery pagoda, but important landmarks in the three-dimensional landscape of Yecheng. The relative position and landscape continued the construction logic and visual effects of the Buddhist pagodas of Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery in Luoyang of the Northern Wei (see

Figure 2).

An excellent case of Buddhist influences occupying the axis of the capital concerns the performance activity on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month (the birthday of Buddha in Chinese tradition). A few days before the birthday, Buddha statues from the entire city left their monasteries and gathered on the square of Jingming Monastery in the south of Luoyang, surrounded by guards of honors and believers. On that special day, the parade line of statues departed from Jingming Monastery and went north until they received the emperor’s flowers and respect in front of Changhe Gate, the main gate of the palace (

Yang 2018, pp. 133–34). During this period, the division caused by the well-ordered

Lifang system of the capital in Medieval China was briefly broken, as Buddhist influences maintained the most important and political symbolic axis from Taiji Hall, Changhe Gate to Xuanyang Gate, on this special day. The political axis of the capital profoundly reflected the integration of Buddhism with imperial power. Yet there were limitations: Firstly, there was no permanent Buddhist architecture on the central axis, and the emergence of Buddhist influences (the parade of Buddhist statues) on it was still temporary. Secondly, the parade of Buddhist statues stopped in front of Changhe Gate, without entering the core area of the imperial palace.

As represented by Luoyang, the capital of the late period of the Northern Wei, Buddhist monasteries and pagodas, whether in two or three dimensions, effectively interacted with the political axis of the capital in an orderly distribution on both sides of it, showing a trend of continuous growth in influence on the capital landscape. In the performance activities on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, Buddhist influence even temporarily occupied the political axis of the capital itself.

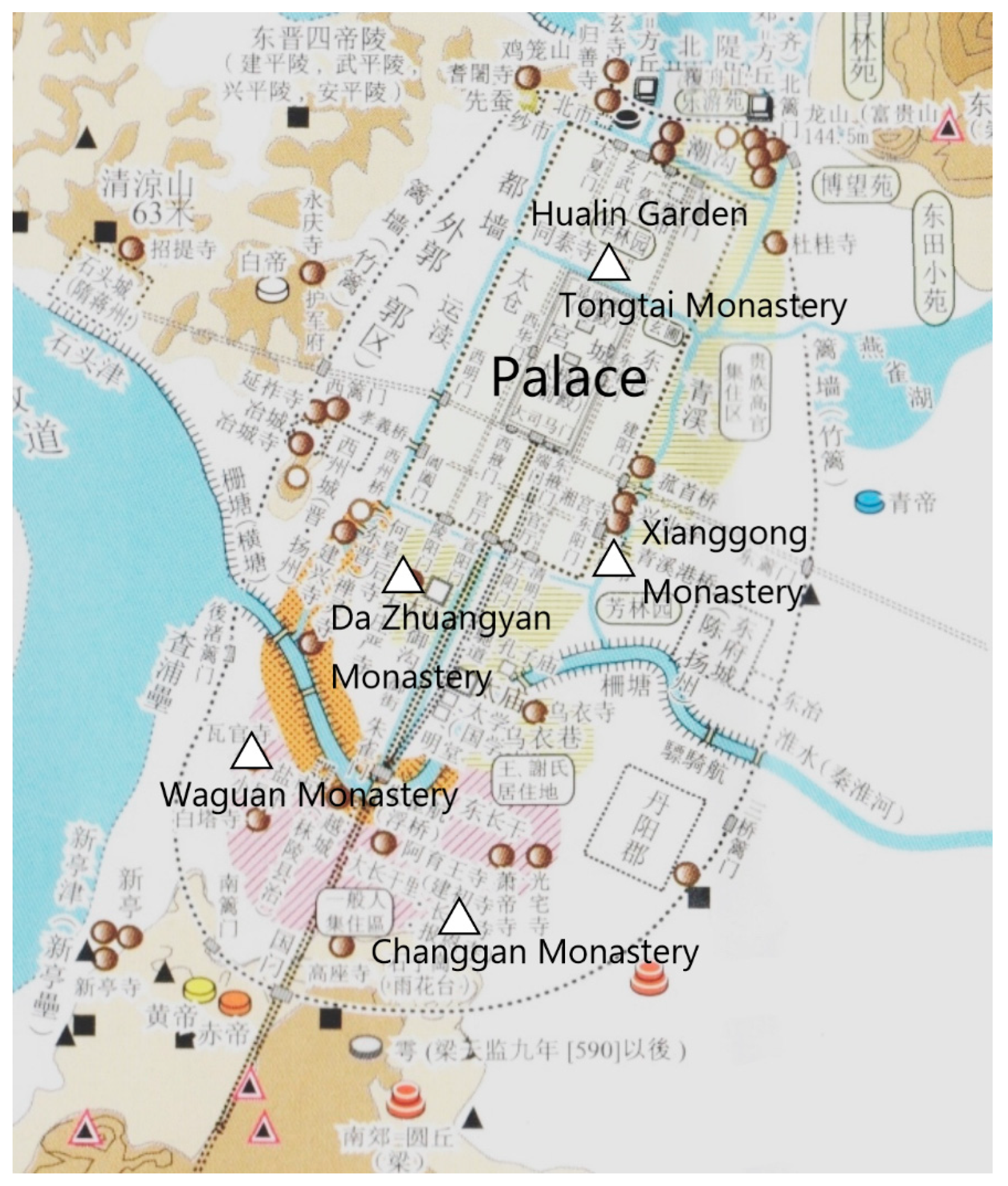

3. The Development of Buddhist Architecture in the Capital of the Southern Dynasties (420–589) and the Breakthrough of Tongtai Monastery

Buddhism during the Southern Dynasties integrated with the political culture of the capital. Due to the large number of monasteries in the capital, Jiankang (nowadays Nanjing), the title of “four hundred and eighty monasteries of the Southern Dynasties” was coined. According to the historical records, Jiankang City during the Eastern Jin and the Southern Dynasties was roughly composed of three areas: the palace, the inner capital city, and the outer city. From south to north, the southern part of the city consumed a broad space and was composed of a southern suburban ritual architecture area, a civilian residential area, commercial districts, and residential areas of princes and nobles on both sides of the Huai River (i.e., the Qinhuai River); to the north were the district of the official institutes, the palace, the Hualin Imperial Garden, and other imperial gardens. The important monasteries during the Eastern Jin, Changgan Monastery (originally Jianchu Monastery) and Waguan Monastery, were arranged on the east and west sides of the capital city axis, namely, the

Changgan Li area in the broad sense, defined by Xu Zhiqiang (

Seo 2019, Figure 75;

Zhang 2021, pp. 340–54). Changgan Monastery had an especially sacred status due to the bone relics of the Buddha unearthed there and thus was recognized as one of the most significant monasteries of Jiankang Buddhism in the Eastern Jin to the early Southern Dynasties periods. This was also where the Ashoka Pagoda was located.

13 The relative relation between its location and the axis of the capital city was also similar to the relation between Jingming Monastery and the political axis of Luoyang during the Northern Wei. However, because the city planning of Jiankang from Eastern Jin to the Southern Dynasties was not as meticulous as Luoyang in the late period of the Northern Wei, it is difficult to make clear whether the plan’s relation with the central axis concept was accidental or the result of prior planning.

The imperial monastery in Jiankang during the Southern Dynasties was Da Zhuangyan Monastery, built by Liu Jun, Emperor Xiaowu of Song (430–464, r. 453–464) (

Xiao 2017, p. 1010). The title of this monastery was also witnessed in Ye of Northern Qi and Chang’an in Sui and Tang (581–907). The prefix

da (“great”) was added to the monastery title in demonstrating its important and prominent status. During Emperor Xiaowu’s reign, the court of Song had already built a seven-story pagoda as the highest pagoda in Jiankang, earlier than the huge pagoda of Yongning Monastery with the same number of stories. In addition, its geographical location was not far from the political axis of Jiankang. It was located on the west side of the Ancestral Shrine on the north bank of the Huai River, and was adjacent to the district of official institutes on the north side.

14 Judging from this location, to compare with the locations of Changgan and Waguan monasteries in

Changgan Li to the south, the location of the Da Zhuangyan Monastery was closer to the core area of imperial power and the political axis of the capital (see

Figure 3).

Later, Liu Yu, Emperor Ming of Song (439–472, r. 466–472), who seized victory in the struggle for court power, desired to surpass his half-brother by building a ten-story super-high pagoda in Xianggong Monastery, his former residence on the east side of the palace in Jiankang. However, technical limitations prevented his grand plan from being fully realized. In the end, he could only take the expedient method to build two five-story pagodas to compose a conceptual ten-story pagoda. In the process of building the pagoda, Lu Yuan once bluntly persuaded him to stop the project. However, in Liu Yu’s view, the construction of the pagoda had great merits and its own important meanings and functions. It was not a “face-saving project” that wasted labor and money (

Xiao 2017, p. 1010;

Li 1975, p. 1710). Because the location of the pagoda was the old residence of Emperor Ming of the Song Dynasty, it was located to the east of the palace, and a certain distance from the political axis of the capital was maintained.

During the Liang Dynasty (502–557), Xiao Yan, Emperor Wu of the Liang (464–549, r. 502–549), named the “Bodhisattva Emperor,” greatly admired Buddhism. According to

Liangshu and

Xu Gaoseng Zhuan, Emperor Wu once built the famous Da’aijing Monastery in Mount Zhong, in the northeastern suburb of Jiankang (

Yao 1973, p. 159;

Daoxuan 2014, p. 9). According to

Jiankang Shilu, the Da’aijing Monastery was built in the first year of the Putong period (520). Based on a different text, the “

Da’aijing Si Chaxia Ming (Inscription under the spire of Pagoda of Da’aijing Monastery),” written by Xiao Gang, Emperor Jianwen (503–551, r. 549–551), a seven-story pagoda was built in Da’aijing Monastery in the third year of the Putong period (522) (

Li 1966, p. 4149a). Although the Da’aijing Monastery was built by Emperor Wu with a seven-story pagoda, and Emperor Jianwen himself wrote the inscription under the spire of its pagoda, it was located on Mount Zhong (now Zijing Mountain in Nanjing) to the northeast of Jiankang. There was a considerable distance between this monastery and the political axis of the capital and the palace. Thus, by the middle period of Emperor Wu, distance between the Buddhist architecture of the Southern Dynasties and the political axis of the capital still existed (e.g., Da Zhuangyan Monastery, Changgan Monastery, etc.).

In the first year of the Datong period (527), after completing the construction of the seven-story pagoda of Da’aijing Monastery in Mount Zhong, Emperor Wu also started construction on Tongtai Monastery in Hualin Garden to the north of the palace in Jiankang. According to the “Biography of Shi Baochang” in

Xu Gaoseng Zhuan,

“In the first year of the Datong period, the Datong Gate was opened in the north of Taicheng (in the palace), and Tongtai Monastery was established. The pavilions and halls in it were established to follow the imperial standard of palace; and the nine-story pagoda was remarkably high, [sic, as if] to float on the cloud. There were many hills, trees, gardens and ponds located in it. On the sixth day of third lunar month, the emperor came to this monastery to tribute the Buddha ritually. This had become a routine and standard”.

Tongtai Monastery had a competitive relationship with Yongning Monastery in

Weishu and

Luoyang Qielan Ji on three levels (

Wei 2017, p. 3306;

Yang 2018, pp. 11–13). Firstly, the number of stories of the Tongtai Monastery pagoda was also nine, which was the same as the pagoda of Yongning Monastery in Luoyang; secondly, the pavilions and halls followed the imperial standard of the palace; and thirdly, Emperor Wu, as Empress Ling and Emperor Xiaoming did in the Northern Wei, visited Tongtai Monastery after its completion. According to

Nanshi and

Jiankang Shilu, the title of Tongtai Monastery was the inverted word “Datong” in Chinese (

Li 1975, p. 205;

Xu 1986, p. 477); thus, it was directly related to the new reigning title of Emperor Wu and had distinctly political attributes. In the following two decades,

16 Tongtai Monastery became famous for the four times of ordination rituals of Emperor Wu of the Liang, and became the most important imperial monastery in the Liang Dynasty. Every time Emperor Wu of the Liang went to Tongtai Monastery to give up his secular life, he was accompanied not only by large-scale Buddhist activities such as Pañcavārṣika Assemblies (

Chen 2006, pp. 43–103), but also by steps for amnesty and a change in a new reigning title.

The Tongtai Monastery was in the Hualin Garden adjacent to the Datong Gate in the south, which was the north gate of the palace of the Liang. Although it has not been clearly excavated, based on historical records and the hypothesis of Seo Tatsuhiko and others, Tongtai Monastery was located on the political axis of Jiankang, the capital of the Liang (

Seo 2019, Figure 75). This pagoda was similar in number of stories to the pagoda of Yongning Monastery in the Northern Wei, yet it was located closer to the core of power of the capital. Although the location of Yongning Monastery had moved to the area of institutions next to the palace, it was still located on the side of the political axis of Luoyang in the Northern Wei; Tongtai Monastery had completely and permanently occupied the northern part of the political axis of Jiankang, the capital of the Liang, located in the imperial garden behind the palace, as the representative and symbolic axis of power-sharing with Taiji Hall, the highest power symbol of imperial authority. From the perspective of the capital landscape, the pagoda of Tongtai Monastery was like a “background version” of the palace. Its huge volume and shocking height reflected supremacy amidst imperial monasteries, on the same power axis landscape as Taiji Hall in front of it.

On one night in 546, as Emperor Wu explained Buddhist sutras and held Buddhist rituals at Tongtai Monastery, a fire broke out, and the pagoda of Tongtai Monastery burned to the ground (

Yao 1973, p. 90). Nonetheless, Emperor Wu did not abandon his grand ambition to build a higher and larger landmark building on the most important political axis. The construction plan for a twelve-story pagoda was put on the agenda. This remarkably high pagoda was not completed in time, ending because of Hou Jing’s rebellion and Emperor Wu’s tragic palace confinement (

Xu 1986, p. 478). For Emperor Wu, the positions of Tongtai Monastery and its pagoda were comparable to Taiji Hall in symbolizing supreme power. They served as permanent fixtures on the political axis of the capital and as one of the most important political landscapes.

This model may also have affected the construction and site selection of

Queli (Cakra) Buddhist Monastery in Ye, the capital of the Northern Qi. The word

Queli is related to the giant skyscraper built during the Kaniṣka period of the Kushan Empire (127–150), the Kaniṣka Stupa, which was the so-called “Queli Futu,” as recorded in the biography of Faxian and the biographies of Song Yun and Daorong (and quoted in the

Luoyang Qielan Ji and

Datang Xiyu Ji;

Faxian 2008, p. 33;

Yang 2018, pp. 228–29;

Xuanzang and Bianji 2000, pp. 60–61). In September 1908 and November 1910, Dr. D. B. Spooner led a team to excavate the ruins of Cakri Stupa in Shaqikiteri, outside Peshawar (

Sun and He 2018, p. 433). According to Sun Yinggang, “The so-called

Queli Futu means the stupa of Cakravartin. Queli means Cakri, which means the Wheel Treasure” (

Sun 2015a, p. 126;

Sun 2019, pp. 30–44). According to his argument, the so-called

Queli Futu thus signifies the stupa of Cakravarti-raja.

The title of

Queli Foyuan (Cakra Buddhist Monastery), located in Hualin Garden (

Li 1972, p. 173;

Sima 1956, p. 5281), the imperial Garden of Yecheng in the Northern Qi, directly copied the word

Queli, meaning “Cakravarti-raja.” Different from the location of the pagoda of Yongning Monastery in the Northern Wei, this Buddhist monastery was also located in Hualin Garden

17 to the north of the palace in Ye, and thus on the imperial and political axis. The location of Queli Buddhist Monastery was like the location of Tongtai Monastery in the Liang, and different from the location pattern of Yongning Monastery and Jingming Monastery in the Northern Wei. Whether the appearance of this form at the end of the Northern Dynasties was directly affected by the model of Tongtai Monastery in the Liang is still hypothetical. However, judging from the close contacts and interactions between the northern regime and the southern regime from the late period of the Northern Wei to the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi periods, there is the possibility that the builders of the Northern Qi were influenced by the Southern Liang.

In Daxing City (nowadays Xi’an), newly built in Sui (581–618), the largest monasteries to occupy one

fang, such as Da Zhuangyan Monastery and Da Zongchi Monastery, stood side by side at the southwest corner of the outer city. Two pagodas standing opposite each other with a height of three hundred

chi had also become the most important religious fixtures in the southern part of the capital (

Wei 2006, pp. 69–70;

Song 1991, p. 141;

Su 1997, pp. 29–33). However, the two highest-ranking imperial monasteries were far away from the political axis of Daxing City and the main hall of the imperial palace (Taiji Hall), different from the relations amidst the monasteries of the Northern and Southern Dynasties. Da Xingshan Monastery and Jianfu Monastery in Chang’an during the Tang, however, in the capital planning of Chang’an in Sui and Tang, were imperial Buddhist monasteries close to the central axis.

18 Buddhist architecture did not follow the footsteps of Emperor Wu of the Liang and Queli Buddhist Monastery in the Northern Qi in occupying the political axis of the capital for a long time or even permanently. The basic pattern composed by the main halls of the palace and multiple main city gates, palace gates, and imperial avenues on the axis of the capital remained unchanged. The location of Buddhist buildings was still only close to this axis, not on it (see

Figure 4).

4. The Pinnacle of the Buddhist Political Landscape: The Reshaping of the Luoyang Axis Landscape during Wu Zetian’s Era (684–705)

Another dramatic change was the construction of a series of imperial ritual buildings with Buddhist elements, such as Mingtang (Bright Hall), Tiantang (Hall of Heaven), and Tianshu (Heaven Pillar) during the Wu Zetian era. According to the records of

Zizhi Tongjian, the plans to establish a Mingtang were often discussed during the reigns of emperors Taizong (598–649, r. 627–649) and Gaozong (628–683, r. 649–683). However, the Confucian scholars involved were indecisive, and came to no conclusion. The Mingtang was not completed until much later. After Gaozong died and Wu Zetian (624–705, r. 690–705) came to power, Confucian scholars following traditional Confucianism believed that the Mingtang should be built within three

li (almost 452 m) and seven

li southeast of the capital. Empress Wu considered that the distant location was too far away from the palace, so in 688, Qianyuan Hall, the main hall of Luoyang Palace in the Tang, which was the former site of Qianyang Hall in the eastern capital of the Sui, was destroyed and replaced by the Mingtang, with the monk Xue Huaiyi (662–694) as the overseer of the project (

Sima 1956, p. 6447). Controversy ensued between the Confucian group and the pro-Buddhist forces represented by Xue Huaiyi. Obviously, Wu Zetian did not act according to the suggestions of Confucian scholars, but raised a new plan, trying to build a unique new

mingtang with Buddhist elements.

In 1988, Wang Yan et al. published a brief report on the excavation of Wu Zetian’s Mingtang site (

Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo Luoyang Tangchengdui 1988, pp. 227–30, Figures 3 and 4), the location of which has been disputed (see

Yu and Li 1993, pp. 90–98;

Xin 1989, pp. 149–57;

Wang 1993, pp. 949–51;

Yang 1994a, pp. 154–61;

Yang 1994b, pp. 94–97). Since the beginning of the Tang period, especially during the Gaozong period, important court ceremonies were held at Qianyuan Hall of Luoyang Palace. Wu’s purpose for building the Mingtang here was not to build a ceremonial building, a Mingtang in the style of Wang Mang (BCE 45–CE 23) or the Eastern Han (

Liu 2009, pp. 490–94;

Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 2010, pp. 80–125) (single-story, multiple eaves, located in the southern suburbs), but to create a huge hall located in the center of the palace—the geometric center of the palace, the imperial city (

Fu 2001, p. 21;

Wang 2020, p. 137), and the center of the universe (see

Figure 5).

Buddhist characteristics of Wu’s Mingtang concern five aspects: the person who presided over the construction, the external form, the decorative elements, the internal display, and the general function.

Firstly, the person who presided over the construction, as mentioned above, was Wu’s favorite monk, Xue Huaiyi. However, only six years after this Mingtang was built, it was reduced to ashes in the unprecedented tragic fire in 695. According to

Jiu Tangshu and

Zizhi Tongjian, the fire was caused by Xue’s grievances and subsequent arson when he discovered Shen Nanqiu, an imperial physician who was patronized by Wu Zetian. Wu was ashamed and kept silent about the reason for the fire (

Liu 1975, p. 4743;

Sima 1956, p. 6499). In an earlier record,

Chaoye Qianzai by Zhang Zhuo, it is simply stated that Gongde Hall (the Hall of Heaven) was on fire, which extended to the Mingtang, without saying that it was caused by Xue’s arson (

Zhang 1979, pp. 115–16). To be sure, Wu did not intend to hold Xue Huaiyi accountable, and instead continued to appoint him as the person in charge of rebuilding the Mingtang and Heaven Hall (

Sima 1956, p. 6499). In summary, since the principal concept behind Wu’s two Mingtang construction projects was nominally Buddhist, it was natural for Xue to inject more Buddhist influences into the construction process.

Secondly, in terms of the form of the Mingtang, the existing archaeological reports only show its planar structure and scale, and the complex three-dimensional form requires further research. According to Wang Guixiang, due to the strong Buddhist ideological atmosphere and emphasis of belief in the seven-treasures pagodas and multi-treasure pagodas during the reign of Wu Zetian, she desired to create permanent residences of Sakyamuni Tathagata and Prabhutaratna. These structures would serve as metaphors or manifestations of her profound belief in Buddhism. To realize her wish to become a Cakravartin-raja, it was not necessary to build a Mingtang according to the Confucian classics, but to reproduce the wonderful treasure pavilions revealed in the Buddhist classics in order to fulfill her wish to truly become a Cakravartin-raja (

Wang 2011, p. 385). Wang Guixiang found that “the closest structure and spatial form to the building of Wu’s Mingtang is the existing three-story wood-like multi-treasure stone pagoda in front of the main hall of Bulguksa Monastery in Gyeongju, South Korea” (

Wang 2011, p. 387). Specifically, this Silla pagoda, which was built nearly a hundred years after the date of Wu’s Mingtang, had the following characteristics in common: (1) Two of them were three-story pavilion-style buildings, (2) the first story was square with four sloping roofs, (3) both the second and third stories of them were polygonal planes, and (4) the center of these two buildings had a thick central column (

Wang 2011, p. 390). From the Southern and Northern Dynasties (386–589) to the Tang Dynasty, the central column had always been a unique structural form in pagodas. The function of this pillar was structural but symbolized the Buddhist universe column (

Wang 2006, p. 138).

According to Wang Guixiang, the height of the Mingtang was designed to reach ”42

ren,” an explanatory number that has the symbolic significance of Buddhist space. If one

ren was converted to seven

chi, the height of the Mingtang was exactly 294

chi (

Wang 2011, p. 407). Following Wang’s hypothesis for the height and shape of the Mingtang, the shape was different from the previous single-story double eaves Mingtangs as a three-story pavilion with a square and polygonal shape.

Thirdly is the discussion about the decoration of the Mingtang. In this respect, the most representative ones are the decorations of nine dragons and one fire pearl on top of the Mingtang. According to the “Mingtang System” (in Vol. 11 of

Tang Huiyao), Wu’s Mingtang “had three stories: the lower story was the symbol of four seasons, each side with a particular color; the middle story followed the principle of zodiac, with a round cover, and a top plate with nine dragons holding it; the upper story followed the principle of twenty four solar terms, and it also had a round cover” (

Wang 1955, p. 277;

Sima 1956, pp. 6454–55). Sun Yinggang maintains that Wu Zetian decorated the Mingtang with nine dragons, and there were several golden dragons and a fire pearl at the top, which actually reflects the narrative theme of the spit of water by nine dragons, a popular motif in Buddhist visual culture. As early as the Northern Dynasties, the spit of water emitted by nine dragons had already been used for political purposes. The spit of water by nine dragons above Wu’s Mingtang was actually an empowerment ritual. Empowerment was a necessary ceremony for ascending to the throne of Cakravartin-raja (

Sun 2015b, p. 46). In this context, the theme of nine dragons on top of the second story of the Mingtang was not just a symbol of the emperor’s supreme authority but also a visual representation of the initiation ceremony of the Buddhist Cakravartin-raja.

In the first year of Zhengsheng (695), the old Mingtang was completely destroyed by fire, and Wu ordered a new Mingtang to be built. The scale of the new Mingtang and the original Mingtang was similar, but the decoration changed, and its name changed from

Wanxiang Shengong to Tongtian Palace. According to

Tongdian and

Jiu Tangshu, the top of the original Mingtang was decorated with a golden bird called

yuezhuo, and the top of the newly built Mingtang was decorated with a precious phoenix (

Du 1988, p. 1228;

Liu 1975, p. 867). The phoenix was believed to be a symbol of a female, and the phoenix on top of the Mingtang thus symbolized one female, Wu Zetian as an emperor. Nonetheless, within a short period of time, the phoenix at the top of the new Mingtang was replaced by a Buddhist fire pearl (

Du 1988, p. 1228;

Liu 1975, p. 867). The use of a fire pearl as the top decoration on a pagoda, or on the ridge of a pointed roof, was especially common in Buddhist buildings from the Southern and Northern Dynasties to Sui and Tang (

Wang 2011, p. 407). Therefore, Wu used a fire pearl as the top decoration of the newly built Mingtang, named it Tongtian Palace, and changed her reigning title to “Wansui Tongtian” (Long Live Communication with Heaven), which further reinforced the prominence of Buddhist influences on the new Mingtang.

Fourthly are the exhibits in Wu’s Mingtang. According to

Zizhi Tongjian, in 692, “Wu Chengsi, the king of Wei, and five thousand other people, suggested to add the title of the Golden Wheel Holy Emperor (to Wu Zetian). On the day of

yiwei, the empress came to the Vientiane Shrine, to accept the title and hold amnesty throughout empire. (The court) made seven treasures include the Golden Wheel. They were displayed in the court for every imperial ceremony” (

Sima 1956, p. 6492). Additionally,

Xin Tangshu and the annotations of Hu Sanxing in

Zizhi Tongjian offer more details on the specific names of the abovementioned seven treasures. According to these records, the seven treasures displayed in the Mingtang were the golden wheel treasure (

cakra), white elephant treasure (

hasti), female treasure (

stri), horse treasure (

asva), jewelry (

mani), general treasure (

parinayaka), and financial officer treasure (

grhapati) (

Ouyang and Song 1975, p. 3482;

Sima 1956, p. 6492). The so-called seven treasures are the most important systematic symbol of the birth of the Buddhist Cakravartin-raja. When a grand imperial ceremony was held, the display of the Seven Treasures of Cakravartin-raja in the Mingtang was undoubtedly the use of intuitive visual symbols to maximize the identity of Wu’s Buddhist Cakravartin-raja. As a result, the seven treasures appeared in Wu’s Mingtang. This practice added undeniable prominent Buddhist characteristics to Wu’s Mingtang.

After the old Mingtang was burned in 694, the nine cauldrons and Chinese zodiac signs to correspond to the twelve earth branches, which are more characteristic of Chinese political and cultural traditions,

21 were displayed in the newly built Mingtang. Eight of these

ding cauldrons were arranged in the eight directions, and each one was 10

chi in width (

Sima 1956, p. 6499). The practice of setting up nine cauldrons in eight directions with simulated imagery of local mountains, rivers, and products of their corresponding prefectures on these cauldrons was a continuation of the tradition of “making

ding to symbolize the 10,000 things,” as described in the ancient literature. Furthermore, this practice also demonstrated Wu’s emphasis on traditional political and cultural symbols. According to Sun Yinggang, “The change of the core ritual implements of the Mingtang from the seven treasures of Cakravartin-raja to the nine cauldrons of a Chinese emperor may be a vivid reflection of the fusion and conflict between two different views of kingship and ideology” (

Sun 2015b, p. 47).

22 Wu also composed a song sung in harmony about moving the cauldrons by herself—a reenactment almost reflecting traditional imperial power. In addition, she also wished to build the Great Instrument, a precision instrument for timekeeping (

Liu 1975, p. 868). The nine cauldrons and twelve gods symbolized position and space, whereas the great instrument symbolized time, and Wu’s hope was to build the Mingtang as a real cosmic clock (

Forte 1988b, pp. 95–139). Although there is no currently available direct evidence for the display of seven treasures in the newly built Mingtang, these traditional Chinese political–cultural characteristics represented by the nine cauldrons in the new Mingtang in a later period created tension with the fire-pearl characteristics of Buddhist culture. The Mingtang may be regarded as complex ritual architecture for an ideal stage illustrating the unity of Wu’s politics and Buddhism.

Fifthly, I wish to discuss the general function of the Mingtang. As Kaneko Shūichi pointed out, the Mingtang was the de facto main hall of Wu Zetian’s regime (

Kaneko 2017, pp. 189–214). The structure was ostensibly a Buddhist hall, where Buddhist ceremonies were often held. Based on the remnants of the Capricorn fish unearthed in the Tang stratum on the west side of the Mingtang, located on the axis of Yingtian Gate of Luoyang Palace, Zhang Naizhu believed that the purpose of Wu’s construction was to imitate the model of King Ashoka in India and set up a Dharma hall to hold Pañcavārṣika Assemblies with vivid Buddhist influences inside the palace (

Zhang 2002, pp. 205–24;

Shang and Pei 2017, pp. 1–7, 24).

When Wu Zetian built the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven for the second time in 695, she accepted the title of

Cishi Yuegu, “Golden Wheel Holy Emperor”; changed her reigning title to Zhengsheng; and identified Maitreya Buddha with the sovereignty of her emperorship and the divine power. Xue Huaiyi hosted an unprecedentedly grand Pañcavārṣika Assembly in the new Mingtang (

Sima 1956, pp. 6497–98). For this grand Buddhist ritual, the Mingtang was decorated with majestic Buddhist objects such as fabrics, Buddha statues, and Buddhist paintings, and was transformed into a Buddhist ritual hall. According to

Zizhi Tongjian, “on the

yiwei day (of the first year of the Zhengsheng period [695]), a Pañcavārṣika Assembly was held in the Mingtang…(they painted) a large Buddhist portrait whose head measured 200

chi. It was said that Huaiyi stabbed his knees and used his blood to paint it. On the

bingshen day, the portrait was displayed in the south of Tianjin Bridge” (

Sima 1956, p. 6498). At the peak of Wu’s worship of Buddhism, the Mingtang was not only the place for general administrative business, but also the place where Buddhist Pañcavārṣika Assemblies were held. This function was like that of Tongtai Monastery of Emperor Wu of the Liang. Compared with the pagoda of Tongtai Monastery and Queli Buddhist Monastery of the Northern Qi, its position went further, being in a location directly at the center of the power space of the capital. It is worthy of special attention that this huge Buddha portrait was later set up south of Tianjin Bridge. Tianjin Bridge was located over the Luo River on the political axis of Luoyang. The display of the giant Buddha portrait in this place reveals the profound impact of Buddhism on the political axis of the capital during Wu Zetian’s reign.

The Hall of Heaven was built just after the Mingtang, according to the biography of Xue Huaiyi in

Jiu Tangshu: “the great hall of the Mingtang had three stories, with a total height of 300

chi. The Hall of Heaven was built in the north of the Mingtang, and its bottom area was inferior to that of the Mingtang” (

Liu 1975, p. 4742). According to this record, the place of the Hall of Heaven should have been to the north of the Mingtang, and its building area should have been smaller than the Mingtang. Its vertical height should have been above the height of the Mingtang, more than 294

chi. The description of the Mingtang in

Tongdian notes, “Firstly, the Mingtang was established, and then the five-story Hall of Heaven was built behind the Mingtang. The third story, could overlook the Mingtang[…]” (

Du 1988, p. 1228). The size of the statue was described in an extremely exaggerated manner in the record of

Chaoye Qianzai. It showed that the Buddha statue was “900

chi high, with a nose like a thousand-

hu boat, and the nose can accommodate dozens of people sitting side by side” (

Zhang 1979, p. 115). Worship of large-scale Buddha images is documented by a huge lacquer Buddha statue said to have been installed in the Hall of Heaven; its third story was close to the top of the Mingtang, and the total height should have been much higher than the Mingtang. If inferred from the record of the Mingtang’s height of 294

chi, the total height of heaven should have been above 150 m, which is comparable to the pagoda of Yongning Monastery in the Northern Wei.

Perhaps it was precisely because the base of the Hall of Heaven was not as large as the Mingtang, and its height was far above the Mingtang, that the wind resistance of this high-rise building was quite problematic. According to

Jiu Tangshu, “at that time, Wu Zetian made the Hall of Heaven behind the Mingtang, with a statue of Buddha, more than a hundred

chi high. The construction began, and then it was overthrown by strong winds. Soon after, the building was reconstructed again and its work had not been completed finally. On the

bingyin night of the first lunar month, 695, the Buddhist hall burned and affected the Mingtang. Until the morning of the next day, the two halls were burned altogether” (

Ouyang and Song 1975, p. 865). According to this record, the original location of the Hall of Heaven was built on the site of Daye Hall of the Sui. It may not have been completed when burned together with the Mingtang. Seo Tatsuhiko still believes that “This was probably the only example of the construction of a Buddhist hall or pavilion in the center of the imperial palace in Chinese history” (

Seo 2019, p. 188). In Luo Shiping’s view, “the purpose of Wu’s newly built the Hall of Heaven in Luoyang was more than praying for merit, but had the function to advertise the power of emperor from the heaven. With the help of the prophecy of Maitreya Buddha to be Wu Zetian, it is possible to see Wu Zetian and Maitreya Buddha as the same. The Buddha statue in the Hall of Heaven should be regarded as a monument built by Wu Zetian for her enthronement” (

Luo 2021, p. 252).

After the fire, Wu Zetian did not abandon her plan to rebuild the Hall of Heaven. According to the note in the paragraph of Mingtang in Du You’s

Tongdian,

“To rebuild the Hall of Heaven, the scale was lower and narrower than the original one. A huge Buddhist statue was displayed in the Hall of Heaven and a great instrument was also installed After the Hall of Heaven was burned, and the voice of the bell (the great instrument) disappeared. In the reign of Zhongzong (656–710, r. 684, 705–710), he wished to follow and complete the plan of Wu Zetian, and cut the statue to make it short, and build Shengshan Monastery Pavilion to display it”.

Although the newly created Hall of Heaven was used to install the Buddhist statue, its size had been reduced. After the fire, Emperor Zhongzong, the third son of Wu Zetian, wanted to continue his mother’s plan, so he cut off the giant Buddha statue in the middle, reducing its height, and then built a new pavilion to install it. According to Xu Song, in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), although the Hall of Heaven had not been rebuilt, Foguang Monastery was built in its location (

Xu 2019, p. 341). After the fire, Wu adjusted the furnishings in the Mingtang, replacing the seven treasures, which symbolized the Buddhist Cakravartin-raja, with nine cauldrons, which symbolized nine Chinese prefectures, marking a retreat of Buddhist influences. Changing the precious phoenix at the top of the Mingtang to the fire pearl, and replacing the name of the Hall of Heaven with the title of Foguang Monastery, Buddhist influences continued to occupy the core area of the palace and political axis during the later period of Wu Zetian’s reign.

As for the verification of archaeological materials, in the report on the excavation of the site of the Hall of Heaven in Luoyang during the Sui and Tang, archaeologists directly identified the base of the circular building on the northwest side of the Mingtang site in Luoyang as the Hall of Heaven of Wu Zetian (

Luoyangshi Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiuyuan 2016, p. 114). However, this round building to be identified as the Hall of Heaven did not appear on the site of the Daye Hall of the Sui, located in the north of Qianyuan Hall (Mingtang) in the Tang. Before a comprehensive archaeological excavation takes place to the northeast of the current round building site, the location of Daye Hall in the Sui, there seems to be another possibility: that the cleaned-up site may not be the site of the Hall of Heaven by Wu Zetian, but rather the site of Foguang Monastery that was later rebuilt, and even the site of Shengshan Monastery Pavilion built by Zhongzong. If so, the Hall of Heaven, or Foguang Monastery, which had the attributes of a Buddhist hall, may possibly have been removed from the political axis after being destroyed and repositioned to the northwest of the Mingtang. As for the time of this change, it is unknown whether it was at the time of the construction of Foguang Monastery or the time when Shengshan Monastery Pavilion was re-established by Zhongzong.

Another possibility is to turn to admitting the views of archaeologists, who believe it is incorrect that the Hall of Heaven was built to the north of the Mingtang and the location of the Daye Hall, based on historical materials. Why the Hall of Heaven was placed northwest of the Mingtang may be relate to the position of

Qian, a hexagram corresponding to heaven in the Houtian Eight Diagrams. This explanation corroborates to the judgment of archaeologists that the site of the Hall of Heaven is “the only round building in the palace buildings in ancient China” (

Luoyangshi Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiuyuan 2016, p. 114). According to

Jiu Tangshu, when the Hall of Heaven caught fire, cloudless thunder appeared in the northwest, the so-called

Qian position in the Houtian Eight Diagrams (

Liu 1975, p. 865). This argument also provides a certain degree of logical support for establishing a connection between the Hall of Heaven, heaven, and the

Qian position in the northwest. However, there is still an obvious contradiction between it and the argument of establishing a hall of heaven on the site of Daye Hall, to the north of the Mingtang according to historical records.

Despite the above disputes, it is certain that “the two buildings were both located in the center of the palace, and the relations between Buddhist architecture and the central building as the political arena were closely integrated, supporting and complementary to each other. The close connection between the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven reflected the ritualization process of Buddhist architecture around 694 in the reign of Wu Zetian” (

Yang 2013, p. 390).

Outside of the palace where the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven were located, the most noteworthy political landscape on the political axis of Luoyang during the Wu period was Tianshu (Heaven Pillar) of the Great Zhou Dynasty. This huge structure to the north of the Luo River took only eighth months, from 694 to its completion in 695. The purpose of building Tianshu was to commemorate the successes and merits of Wu Zhou (Zhou Dynasty of Emperor Wu) and praise Wu Zetian’s achievements. According to Liu Su’s record, “In the third year of the Changshou period (694), Wu Zetian collected more than 500,000

jin of copper, 3.3 million

jin iron, and 27,000,000 coins from within the whole empire, to establish an eight-sided bronze pillar in the front of the Dingding Gate. It was ninety

chi high and twelve

chi in diameter. The title was ‘The Heaven Pillar to record the successes and merits of Great Zhou’, which records the achievements of the revolution and derogates the imperial virtue of the Li family. Under the Tianshu, there was an iron mountain, held by bronze dragons, surrounded by lions and unicorns. There was a cloud canopy, decorated by round dragons to hold a fire pearl. The pearl was 10

chi high and 30

chi circumference. Its golden color was shining brightly to compare with the light of sun and moon” (

Liu 1984, p. 126).

Luo Xianglin discussed the relationship between Nestorian Arohan and Tianshu; Li Song started with the analysis of its external form and compared it to stone pillars with Buddhist inscriptions and tomb pillars in the Southern Dynasties. Li maintained that the column was popular at that time. Forte analyzed the construction and abandonment of Tianshu;Zhang Naizhu argued that the construction of Tianshu was influenced by the monumental architectural culture of the Western Regions, such as the Ashoka Stone Pillars and Trajan’s Column.

23 In recent years, decorative patterns such as lions and the fire pearl on Tianshu were analyzed by Chen Huaiyu and Peng Lihua (

Chen 2012, p. 308;

Peng 2020, pp. 31–50;

2021, pp. 26–50). The Tianshu monument appears similar to the form of the Ashoka Pillars (

Zhang 1994, pp. 44–46), decorated with the fire pearl and stone lions, and surrounded by the so-called Iron Mountain, which symbolizes the

cakravda in the Buddhist world, or its symbolic meaning as a pillar to connect earth and heaven. These Buddhist symbols amplified Wu’s great ambitions as Cakravartin-raja, the lord of the world.

To sum up, in the early and middle periods of Wu’s reign, the Mingtang, an example of Confucian ritual architecture with obvious Buddhist elements, and Tianshu, which was closely related to the nature and form of the Ashoka Pillars, were located in the geometric center of the palace and the small island to the north of Tianjin Bridge and south of Duan Gate, to occupy the most prominent positions on the political axis of the sacred city, Luoyang, symbolizing the center of the world. The Hall of Heaven, built by Xue Huaiyi to install a giant Maitreya statue, was possibly located in the foundation of the Daye Hall to the north of the Mingtang. After being destroyed by fire, it was renamed Foguang Monastery. The other possibility is that the Hall of Heaven was always located northwest of the Mingtang, in corresponding to the position of

Qian, symbolizing heaven in the Houtian Eight Diagrams, without its position ever having been moved. In the process of displaying the seven treasures symbolizing the power of Cakravartin-raja, welcoming the Buddha bone relics,

24 and holding an unprecedented scale of the Pañcavārṣika Assembly, the Mingtang, as a traditional Confucian ritual space, played an extremely important political role. If the political axis of Luoyang, the sacred capital of Wu Zetian, was extended to the south, its southern endpoint would have been the Longmen Grottoes on the west bank of the Yi River. In the capital of Wu, Buddhist space and buildings were no longer limited to “giving up the main axis and occupying the two compartments,” but composed the primary political axis and cosmological axis in the capital. The most symbolic and representative so-called “Seven Heaven Architectures” on the political axis of Luoyang during the reign of Wu Zetian included Tiantang (Hall of Heaven), Tiangong (Mingtang), Tianmen (Yingtian Gate), Tianshu (Heaven Axis), Tianjin (Tianjin bridge), Tianjie (Heaven Avenue), and Tianque (Longmen Grottoes in Yique Valley), and buildings (or grottoes) with clear Buddhist influences made up four of these seven. Wu’s construction of the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven on the political axis of Luoyang, the sacred capital, had a certain logical connection with the actions of Emperor Wu of the Liang. As Chen Jinhua said, all three key components of Wudi’s palace chapel—the Chongyun Hall, the Sanxiu Pavilion, and the astronomical edifice (called Cengcheng Cengchengguan, Chuanzhenlou, or Tongtianguan)—have their counterparts in Wu Zetian’s Mingtang complex (

Chen 2006, p. 92).

5. The Return to the Model of the Southern and Northern Dynasties: The Relation between Architecture of Buddhist Influences and the Political Axis of the Capital in the Post-Wu Zetian Era

Too much water drowned the miller. The fires of the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven in the middle and late periods of Wu Zetian’s reign foretell the decline of Buddhist influences in the political axis of the capital. Wu did not completely abandon the construction of large-scale Buddhist buildings with political symbolism. After she moved the ruling center back to Chang’an, she created a stage of seven treasures in Guangzhai Monastery located on the south axis of Daming Palace.

25 The direct sponsors of the statues on this stage were mostly high-ranking officials and monks, rather than Wu herself (

Yang 2013, pp. 363–71). Wu insisted in her later years on building a giant Buddha statue in Bai Sima Ban, located far away, 30

li northeast of Luoyang, but she was opposed by Di Renjie (630–700), Li Qiao (645–714), Zhang Tinggui (663–741), and others, and ultimately failed (

Matsumoto 1934, pp. 13–49;

Hida 2010, pp. 130–36). Evidently, the direct occupation of the political axis of the capital axis by Buddhist buildings only existed in the period when Wu officially proclaimed herself the emperor.

This rebuilt Mingtang was still used until Xuanzong’s reign (712–756). In 717, Emperor Xuanzong (685–762, r. 712–756) issued an edict: “Nowadays the Mingtang is located next to the palace. It is not correct or adequately respectful to compare with the ritual requirements. If it did not follow the Confucian principle, what is the model of this building?” (

Ouyang and Song 1975, p. 178). Emperor Xuanzong thought that the location of the Mingtang was too close to the palace and that the height was too high. Emperor Xuanzong ordered ritual masters, high-ranking officers, to discuss this topic together, and later renamed the Mingtang the Qianyuan Hall, the original name of the building before the Mingtang was built. In 722, Xuanzong, without explanation, “re-named Qianyuan Hall as Mingtang again” (

Ouyang and Song 1975, p. 184). In 739, “the upper story of the Mingtang in the eastern capital (Luoyang) was destroyed, and the lower two stories were rebuilt as Qianyuan Hall” (

Ouyang and Song 1975, p. 212). According to the paragraph of the Mingtang system in

Tang Huiyao, Xuanzong’s initial plan was to demolish the Mingtang entirely, in ordering an imperial master craftsman to go to the eastern capital to carry out the demolition. In the end, the emperor simply suggested demolishing the top story of the building and reduced its height to two-thirds of the original height. The center wood pillar was removed, and an octagonal building was placed on the middle story between the first and second stories, with eight dragons rising to hold a fire pearl. The size of the fire pearl was also smaller than the previous one (

Wang 1955, p. 281).

This approach was obviously a degradation in terms of building regulations. A similar practice was seen in Qianyang Hall of Luoyang in the Sui and Qianyuan Hall in the same location in the early Tang. The location of the two halls was the location of Wu’s Mingtang, which was the main hall of the imperial palace. According to Wang Guixiang’s textual research, Qianyang Hall in the Sui had three eaves, whereas Qianyuan Hall in the Tang had only two eaves, and the height difference between the two was exactly 50

chi (

Wang 2012, p. 129). The degradation of the main hall of Luoyang Palace in the early Tang was obviously related to the fact that the capital was set in Chang’an during this period, and Luoyang once lost its status as the eastern capital. In the later period of Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty, especially after Wu Zetian established the Great Zhou Dynasty and established Luoyang as the actual capital (the so-called sacred capital), the status of Luoyang rose sharply, and the magnificence of the Mingtang was an intuitive manifestation of its political status. After Emperor Xuanzong re-established Chang’an as the only central political center, the status of Luoyang was reduced again. After 739, the demolition plan of the Mingtang and its final reconstruction and ultimate degradation became a logical and inevitable result.

As for the demolition of the center pillar of the Mingtang, the reduction of nine dragons into eight dragons, and the reduction of the size of the fire pearl, they all clearly reflect the reduction of Buddhist influences, in addition to the abovementioned downgrading requirements. As mentioned earlier, the major features of Wu’s Mingtang differentiated from any previous Mingtang buildings in having a multi-story pavilion and a huge core pillar. According to Forte’s research, the Mingtang, which was built for the last time and reconstructed by Emperor Xuanzong, was also called Tongtian Palace. The building had three stories and the top story was a pagoda (

Forte 1988b, p. 174). If Forte’s analysis is valid, the third story of the Mingtang was eventually demolished by Xuanzong, which was the pagoda part. Emperor Xuanzong’s purpose was to remove the material representation of the connection between Buddhism and political culture in Wu Zetian’s reign.

As for the final outcome of this Mingtang (or Qianyuan Hall), built during Wu Zetian’s reign and later rebuilt by Xuanzong, it was completely burned down during the Anshi Rebellion (755–763). According to

Fengshi Wenjianji, Shi Siming (703–761) was killed by his son, Shi Chaoyi (?–763), in 761. The Mingtang and the Shengshan Monastery Pavilion, dedicated to Maitreya, were also burned down (

Feng 2005, p. 35). Up to this period, the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven had completely disappeared and withdrawn from the political axis of Luoyang.

Outside the palace, the other magnificent building in Luoyang during the Wu Zetian period, the Tianshu, was also a target for elimination by Xuanzong. According to

Datang Xinyu, “in the Kaiyuan period, the emperor ordered to destroy Tianshu, and the soldiers took more than one month to melt it” (

Liu 1984, p. 126).

From this point of view, a series of measures such as the reconstruction of the Mingtang and the melting down of Tianshu after Xuanzong’s accession to the throne marked his fundamental reshaping of the landscape of the political axis of Luoyang, with a plan to remove Buddhist influences from the political axis as much as possible. Marked by the aforementioned dramatic transition, the positions of Buddhist buildings in Chang’an and Luoyang after the reign of Xuanzong had once again returned to the model of being to the side (especially to the east side) of the central axis, as it was during the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

In the Song (960–1276), Liao (907–1125), and Jin (1115–1234), the relations between significant Buddhist monasteries and the political axis was as follows: The great imperial monastery in the capital of the Northern Song, Da Xiangguo Monastery, also followed this principle—located in a similar position, but not necessarily the result of pre-planning because it was inherited from previous dynasties. Lin’an (nowadays Hangzhou), the capital of the Southern Song, was particularly special because of its palace sitting in the south. However, the schematic plan shows that only a few imperial or state monasteries, such as Bao’en Guangxiao Monastery, were located on the two sides of the imperial avenue to the north of Chaotian Gate, which was not a completely centralized political axis. The influence of Buddhism on the political axis of the capital was weaker than during the Northern Song. The so-called five capitals of the Liao did not actually operate with a centralized political center. The central capital of the Jin (nowadays Beijing) was expanded following the southern capital of the Liao: The monasteries of Da Kaitai, Da Haotian, Da Wan’an Chan, Tianwang (nowadays Tianning), Faguang, Lingquan Chan, Shousheng, Shifang Wanfo Xinghua, and others gathered on both sides of the political axis of the capital city from the gates of Tongxuan and Gongchen through the palace to Xuanyang and Fengyi Gate in the south.

26 The monasteries of Da Kaitai, Da Haotian, Tianwang, Lingquan, and (Zhaoti) Shousheng had existed on both sides of the south capital of the Liao and were not newly built during the Jin (

Meng 2019, Figures 3–6). The Buddhist buildings on both sides of the political axis of the capitals of the Song, Liao, and Jin, although different in size and scale, maintained the basic model of the Northern Wei and the Xuanzong period of the Tang.

6. Conclusions

During the early Imperial Period of China (the Qin and Han dynasties), the capital adopted a multi-palace system without a political central axis. When Buddhism entered China, Buddhist sites were located in the western suburbs of Luoyang during the Eastern Han Dynasty, and thus were not organically included in the central planning of the capital. Due to limited historical records, the distribution of dozens of Buddhist monasteries in the capital during the Western Jin cannot be documented. The political axis and organic integration of monasteries at the new capital of Pingcheng became prominent during the early Northern Wei Dynasty. In the late period of the Northern Wei, the distribution pattern within Luoyang began to focus Buddhist monuments to the left and right sides of the central axis in the northwest corner of the inner city, forming a political landscape from south to north, with a gradual increase in the number of pagoda stories. Additionally, the parade of Buddha statues on Buddha’s birthday incentivized Buddhism to occupy the political axis of the capital.

During the Eastern Jin through to the early period of Emperor Wu of the Liang, significant monasteries were located on both sides of the political axis of the capital, or to the east of the palace, whereas Da’aijing Monastery, with a seven-story pagoda, was located on Mount Zhong, to the northeast of the capital. A crucial breakthrough occurred in the later reign of Emperor Wu of the Liang. The position of the imperial Buddhist monastery (Tongtai Monastery and its nine-story pagoda) was positioned in the imperial garden on the north end of the palace, occupying the political axis of the capital itself. This situation was also seen in the Queli Buddhist Monastery, which was also located in the imperial garden on the political axis during the Northern Qi.

During the Sui Dynasty and the early Tang dynasties, the imperial Buddhist monasteries did not continue the position of Tongtai Monastery, built in the late period of Emperor Wu of the Liang, but continued the tradition of the Northern Dynasties, arranged on both sides of the political axis of the capital or other areas. During the reign of Wu Zetian, Buddhism and imperial political culture were fused, as is especially marked in the development of Cakravatin-raja thought and its related Buddhist ideology. The Mingtang of Confucian ritual architecture of traditional Chinese political culture was combined with Buddhist decor and design concepts. The seven treasures of Cakravatin-raja were placed in the Mingtang, symbolizing the legitimacy and authority of the Buddhist monarch. More significantly, Wu Zetian also built a higher five-story building (Tiantang) at an important location to the north or northwest of the Mingtang, inside of which was with a monumental Buddha statue. Tianshu, which was quite similar to the Ashoka Pillars, was also placed as an important landmark monument to the north of Tianjin Bridge, which was part of the political axis of Luoyang. In this particular period, the influence of Buddhism not only occupied the political axis of the capital for Emperor Wu of the Liang, but also became rooted into the core area of the palace, highly integrated with imperial power. When the Mingtang and the Hall of Heaven were burned down in fires, Wu Zetian returned to Chang’an. Especially after Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang held power, the second Mingtang, built by Wu, was reconstructed; the metal Tianshu was melted; and the Buddhist influences in the political axis of Luoyang gradually decayed.

In summary, there are two modes of integration and interaction between Buddhism or architecture with Buddhist influences and the political axis of the capital city: First, it can be regarded as typical after the late period of the Northern Wei to locate landmark Buddhist buildings with huge scale, important political influence, or high multi-story pagodas on both sides of the political axis of the capital. This typical mode was considerably stable, lasting from the Northern Wei to the Tang and even extending its influence to the capitals during the Song and Liao. The second mode was atypical, formed in the later period of Emperor Wu of the Liang and developed in the Northern Qi and the reign of Wu Zetian, placing Buddhist buildings or imperial ritual buildings with remarkably Buddhist influences and symbolic meanings directly on the political axis of the capital. This atypical mode was the product of the high integration and close interaction between Buddhism and political culture in the above three periods but considerably related to the emperor’s personal political and cultural orientation.

Buddhism in Medieval China was not only a foreign religious belief, ideology, and culture, but also a new political and cultural factor that penetrated the political system and affected capital planning at the time. Buddhist monasteries (

Appendix A) and pagodas, as well as certain imperial ritual architecture with Buddhist elements, were no longer just testimonies of the Buddha’s actions and the emperor’s personal Buddhist beliefs, but had also become a material carrier, visual representation, and cultural landscape with a high degree of politically powerful symbolism, which constituted new expressions of political power by Chinese rulers.