Abstract

This paper critically examines how the mainstream media in Israel frame the phenomenon of polygamy among the minority Palestinian Bedouin community within the country. We identify four prominent media frames: (1) an “orientalist” frame, which considers Muslim women as in need of saving from their own culture and religion’s oppression by a modernizing state; (2) a “securitization” frame, which links the practice of polygamy to threats to the state’s security and to “Islamic terrorism;” (3) an “existential threat” frame, which reflects the Israeli Jewish majority’s anxieties about a demographic battle between Jews and Muslims in the country; and finally, (4) a “women’s rights” frame, which is the least prevalent, that addresses polygamy from the perspective of women’s equality and equal citizenship, and which is critical of the discriminatory policies of the state. Theoretically, the paper explicates how the media utilizes minority gendered practices to amplify Islamophobic sentiments in relation to a Muslim community, and how alternative framing and the featuring of critical Muslim women’s voices in the media might mitigate such harmful effects.

1. Introduction

Mainstream media discourse has a significant influence on the public because it can reinforce dominant social values and norms (Oswald 1993; Robinson 2001; Bryant and Oliver 2009; Baker et al. 2013). When it comes to minoritized or marginalized communities, the bolstering of dominant social perspectives can further stereotypes and discrimination when such groups are portrayed as problematic (Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Mustafa-Awad and Kirner-Ludwig 2017; Hebbani and Wills 2012; Navarro 2010; Terman 2017; Mastro and Tukachinsky 2012; Saleem et al. 2017). Previous research emphasizes the media’s immense effect on audiences by informing public opinion, generating social change, and influencing attitudes on a variety of political topics (Mustafa-Awad and Kirner-Ludwig 2017). Yet media discourse often reflects hegemonic knowledge intended to convey certain narratives as truth (Baker et al. 2013; Terman 2017; Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Mustafa-Awad and Kirner-Ludwig 2017). As a result, it is increasingly important to question whose narratives are included in the media, particularly in the portrayal of marginalized groups, and whether these narratives reflect engagement with nuanced and diverse perspectives. Because the media has such a powerful influence on public opinion, negative coverage can generate negative consequences for out-groups. When a group receives unfavorable coverage, there is at times an increase in negative perceptions of the group by the public (Al-Hejin 2015; Ehrkamp 2010; Hebbani and Wills 2012; Macdonald 2006; Navarro 2010; Rahman 2012; Saleem et al. 2017; Mastro and Tukachinsky 2012; Das et al. 2009; Kalkan et al. 2009).

Contributing to a critical engagement with dominant media discourses on minoritized groups, this paper explores the representation of Muslim women in the media within non-Muslim majority states. Specifically, we conduct a case study of the ways the mainstream media in Israel—print and online newspapers—and frame the phenomenon of polygamy among the minority Bedouin Muslim community in the country—a subsection of Israel’s 20 percent Palestinian minority community.1 This case can shed light on important aspects of representation. First, due to the minority status of Palestinian Bedouin citizens of Israel, they tend to be underrepresented in the media, with Palestinian women citizens receiving even less representation than male Palestinian citizens. Polygamy, however, has received significant media attention in recent years (Boulos 2021; Sinai and Peleg 2021; Aburabia 2022). Because the practice of polygamy is gendered and cultured in specific ways, it makes for a particularly effective prism through which to examine and evaluate the media’s framing of women of a Muslim minority community within a non-Muslim majority state. Our specific research question, therefore, asks how polygamy among the Bedouin is framed in the Israeli media, and what are the implications of particular frames to the representation of Palestinian Muslim Bedouin women in the country. Israel is a particularly apt context because of the political salience of a minority-majority divide, where problematic frames about minority groups, and specifically women in minority groups, are articulated in an explicit manner (Aburabia 2011; Dinero 2012; Aburabia 2017).

From our empirical analysis of a selection of Israeli news outlets, we inductively derive four frames which shape the representation of Muslim women in Israeli mainstream media discourse on polygamy: First, we have an “orientalist” frame, which considers Muslim women as in need of saving from their own culture and religion’s oppression by a modernizing Western state. Second, a “securitization” frame, which employs a gendered lens to promote stereotypes of criminality, violence, and a terrorist security threat posed by a Muslim minority. Third, an “existential threat” frame that reflects underlying anxieties of the majority Jewish population about a demographic battle with the Muslim minority, which is portrayed as posing a threat to the existence of Israel as a Jewish state and which requires the control of Muslim women’s birthrates. And fourth—and least prevalent—a “women’s rights” frame which addresses polygamy from the perspective of women’s right to equal citizenship, and that is critical of the discriminatory policies of the state. This last frame views the state’s policies as significant contributors to the existence of polygamy.

We conduct qualitative content and discourse analyses to identify the prevalent frames in a selection of Israeli media outlets—across the left-right political spectrum—via the portrayal of the practice of polygamy in the last two decades (2000–2022).2 Our findings suggest a complicated picture. We find four dominant frames, as outlined above, in Israeli media coverage of polygamy among the Bedouin community, but frame choice is largely determined by the political affiliation of news outlets and the sources they use for their articles. Specifically, while right-wing newspapers overwhelmingly rely on the securitization and existential threat frames, left-wing newspapers emphasize the women’s rights frame, while center-leaning outlets show a combination of the women’s rights and the orientalist, culturalist, frames. However, we also find that all news outlets under consideration—to varying degrees—rely heavily on state sources and thus give a large amount of space to negative and inaccurate perceptions of Bedouin Muslim women. The coverage of state actions and policies is given preference, while the space given to the voices of Bedouin Muslim women’s rights activists and women in polygamous marriages remains limited.

Finally, it is important to note our own normative commitment to feminism and equal civil rights. Given this stance, we view the “women’s rights” frame, space for marginalized women’s voices about their own needs and challenges, and their agency as normatively preferable. Conversely, we are critical of the problematic and harmful effects of the other three frames. As we elaborate in the proceeding literature review, the orientalist, securitization, and existential threat frames all represent an entire minoritized community as defective, deficient or deviant. Such a practice, in our view, betrays a degree of racism that we critique from a feminist perspective (Mohanty 1984, 2003; Ahmed 1992; Abu-Lughod 2013).

Before we outline our news sources selection, methods, and results, in the following section we review three sets of literature to situate our analysis: (1) research on the representation of Muslim women in the Western media, (2) the Israeli media’s representation of Arab and Muslim Palestinian women who are citizens of Israel, and (3) the social science research on the phenomenon of polygamy among the Bedouin Muslim minority in the country. The literature review theoretically clarifies the four frames found in our analysis and highlights their relevance in other contexts as well, drawing out the generalizability of the frames to media representation of Muslim minorities in other Western countries.

2. Representations of Muslim Women in Western Media

Western Media representations of Muslims and Islam have often upheld a cultural divide between the West and Islam, thus generating social and cultural resentment towards Muslims in general and those from the Middle East in particular (Powell 2011; Saeed 2007; Johnson 2019; Ahmed and Matthes 2017; Abu-Lughod 2002; Sotsky 2013). Anti-Muslim sentiment in the Western media has a long history, but it grew in salience post 9/11, when Muslim identity was “securitized,” and Muslims were often portrayed as potential security threats and associated with the phenomenon of terrorism (Brown 2006; Saeed 2007; Ahmed 2012; el Aswad 2013; Kellner 2004; Poynting and Perry 2007). Despite the vast racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity within the Muslim world, negative stereotypes of Muslims dominate Western media discourse (Ibid.). This portrayal has constructed the “West” and “Islam” as culturally incompatible, and Islam as a violent, misogynistic, and homogenous religion where Muslims are portrayed as terrorists, uncivilized and patriarchal (Ahmed and Matthes 2017). This overwhelmingly negative narrative, which we associate with a “securitization” frame, can generate public hostility by linking the actions of specific groups to all Muslims, and inaccurately portraying terrorism and political violence as inherent to Muslims and Islam (Terman 2017).

Complicating the picture is the representation of Muslim women in Western media, which for several decades has depicted them as victims of oppression, lacking agency, and in need of saving from Muslim men and from their own “oppressive” religion and culture (Dastgeer and Gade 2016). In this paper, we term this narrative the “orientalist” frame. Muslim women are often subjects of media stereotyping and suffer the intersecting effects of racism and sexism, in addition to the exclusion of their voices within Western narratives. Previous research on the representation of Muslim women in the media finds consistent themes of Muslim women as victims of their own religion and culture as well as in need of “liberation” or “modernization” (Klaus and Kassel 2005; Macdonald 2006; Byng 2010; Navarro 2010; Williamson 2014; Ahmed and Matthes 2017). The practice of veiling has often been considered synonymous with oppression, with little depth of coverage given to the diversity and history of veiling. Frequent reporting by Western media on gender inequality supports the casting of Muslim societies as inherently misogynistic and Muslim women as oppressed victims within patriarchal societies. Western media prioritizes discourses on veiling over reporting on women’s rights to education or women’s civil rights under repressive regimes (Byng 2010; Hebbani and Wills 2012; Navarro 2010). Religion and culture are framed as hindering women’s rights, while other issues such as regime type, conflict, humanitarian crises, and human rights issues are either seen as secondary hindrances to women rights or are largely ignored (Ibid.).

Without different perspectives to challenge dominant narratives, the media remains a powerful influence on shaping the public’s negative perceptions of Muslim women, who are misrepresented and excluded from contributing to and correcting the media discourse that vilifies them. Muslim women have often been spoken about rather than spoken to, reflecting a huge gap in perspective, lack of diversity, and silencing of marginalized voices within Western reporting (Sinai and Peleg 2021). In addition to the Western tendency to connect veiling—and thus the religion of Islam and Muslim culture—to oppression, media coverage on the veil emphasizes incompatibility and cultural differences (Terman 2017). Linking the veil to oppression also serves to assert that Muslim women do not have control over their sexuality or agency, which constructs additional boundaries for migrant Muslim women for securing equal citizenship in states like Germany and France (Hamel 2002; Ehrkamp 2010). The media’s focus on unveiling migrant Muslim women and its use of sexual liberation as a symbol of emancipation, often casts Muslim women as passive yet erotic sexual beings (Posetti 2010). As a result, migrant Muslim women’s modesty expressed through veiling is seen as a contradiction to notions of agency, whereas sexual “freedom” in a reductive and superficial sense is the measure used to determine the degree of women’s freedom and agency (Ibid.). Because Muslim women are cast as visibly different from Western women by Western media, particularly newspapers, this legitimizes Muslim women’s exclusion from non-Muslim societies (Ehrkamp 2010). Lila Abu-Lughod rebukes the interpretation of veiling as a lack of agency and argues against reductionist understandings of certain gendered minority practices, such as the veil, rightly arguing that uncovered bodies are not necessarily guaranteed more equality than covered ones (Abu-Lughod 2002). Furthermore, negative media representations of veiled Muslim women have been correlated with political motivations to prohibit veiling in places such as France and Canada, perpetuating the use of discriminatory laws against Muslim women (Byng 2010; Abu-Lughod 2002; Hamel 2002).

The media rhetoric surrounding the U.S. war in Afghanistan and the fall of the Taliban is an example of strategic narrative focused on liberating Muslim women. The media coverage used women’s rights to justify military involvement in Afghanistan and simultaneously shifted focus away from recognizing the effects of repressive regimes on women’s rights and the U.S. involvement in their installment (Rahman 2012; Stabile and Kumar 2005; Klaus and Kassel 2005; Mackie 2012). Instead, the description of the U.S. as a savior of Muslim women served to further U.S. political interests rather than address the diverse challenges to women’s rights. Here we see an intersection of the securitization and orientalist frames, in a type of “femonationalism” (Farris 2017) that justifies violent state intervention by appropriating and distorting the feminist language of concern for women’s equality.

To sum, the Western media has largely misrepresented Muslim women, and has perpetuated negative stereotypes and generalizations rather than engaging in nuanced discourse and embracing diverse perspectives. The controversy over veiling and other minority practices and the misrepresentation of Muslim women says less about Muslim women and more about the one-sided perception of Muslim women by the Western media and publics. The prejudice surrounding reporting on Muslim women in the Western media warrants a critical analysis to further understand and critique the lack of accuracy of these negative and dominant stereotypes and their harmful effect on the equal citizenship of Muslim women in non-Muslim majority countries (Al-Hejin 2015).

3. Representation of (Arab and Muslim) Palestinian Women in the Israeli Media

Research suggests that the Israeli media’s representation of Arab and Muslim citizens of the state, belonging to the state’s minority Palestinian community, is characterized by xenophobia (Gribiea et al. 2017). Coverage of Arab and Muslim societies often include inaccuracies, harsh expressions of ethnocentrism, and cultural, racial rancor (Ibid.). Baker (2006) has suggested exploring the massive gap between Israeli law, which mandates appropriate media representation for minorities, and actual practice. She finds that the Israeli media’s coverage of Palestinian citizens is profoundly problematic on two levels: first, the Israeli media under-represents the country’s Palestinian citizens. These constitute approximately 20% of Israel’s population (about 80% of which are Muslim, and the rest largely Christian and Druze) yet, they do not appear on television at rates even close to their share of the population. Second, when the Israeli media covers Arabs, it portrays them negatively and tends to overlook their daily social issues and living conditions.

The securitization frame is predominant here, with Palestinian citizens usually appearing in the Israeli news media when they pose a security threat. Specifically, the Israeli media often accentuates their involvement in criminal or disruptive activities, such as theft, murder, honor killings, unruly demonstrations, and strikes (Abu-Guider 2018), and often describes them as extremists threatening the status quo. In addition to portrayals as extremists, the Israeli media portrays Palestinian citizens as more violent, provocative, primitive, irrational, and unreasonable than Jews (Baker 2006). The Bedouin of the Negev are part of the Palestinian minority in Israel that are rarely covered by the Israeli media unless there is a case involving criminal acts, traffic casualties, and the disruption of public order, which include at times accusations of terrorist activities (Gribiea et al. 2017).

Regarding coverage of Palestinian women citizens, feminist media studies have found that Arab women are barely mentioned in the news in Israel, with most of the women covered in the Israeli news being Jewish (Lahav 2010). When the media covers Palestinian women (citizens or non-citizens), it often portrays them as passive victims, unwise political participants, or terrorists, reinforcing stereotypes about Arab and Muslim women (Johnson 2019). Empirical research on Israeli media coverage of Muslim women in general, and Muslim Palestinian female citizens of the state, is scarce to date. Scholarly work (e.g., Shomron and Schejter 2020) has relied on inferences from media representations of women as a whole and Palestinian Israeli citizens in general to examine the impact of media portrayals of Palestinian female citizens. The authors have documented that Palestinian-Israelis comprised 1–4% of characters on Israeli shows and news platforms. They also found that Palestinian-Israelis are usually portrayed unfavorably in the context of violence and crime and with lower socio-economic position and educational background. Less than 20% of Palestinian-Israelis represented on public television had college degrees relative to nearly 60% of Jewish-Israelis represented. Forty-two percent of news coverage of Palestinian-Israelis showed them in conditions related to violations of public order, approximately double the coverage of violations by Jewish-Israelis. The average interview length with Palestinian-Israelis was 2.5 min relative to 3.3 min for Jewish-Israelis. This study concluded that Palestinian-Israelis in general and Palestinian-Israeli women are significantly underrepresented in the Israeli media. Moreover, the underrepresentation hinders the full realization of the capabilities of Palestinian-Israeli women (i.e., capabilities to have a voice, to be informed, to be secure, to have an identity and belong, and to identify and imitate), which is detrimental to their well-being (Shomron and Schejter 2020).

In conclusion, as the research reviewed here suggests, the Israeli media often distorts the reality of Palestinian citizens of the state, depicts them using stereotypes, and marginalizes their news coverage (Abu-Guider 2018). Representing minorities in a negative light, using stereotypes, blaming them for their problems, ascribing fixed and negative roles to them, or simply disregarding their presence, are all common patterns of the Israel media coverage of Palestinian citizens (Baker 2006).

4. Polygamy and Israel’s Bedouin Community

We chose to conduct a study of the Israeli media’s coverage on the practice of polygamy among the country’s minority Bedouin community as a case study that can shed light on several important aspects of representation. First, the practice itself is gendered and cultured in specific ways that make it a particularly effective prism by which to evaluate the media’s framing of women belonging to a Muslim minority community. Second, given the underrepresentation of Arab-Palestinian women in Israeli media, the fact that in 2017 the Justice Minister at the time, Ayelet Shaked, decided to publicly tackle the issue of polygamy in the Bedouin community meant an uptick in coverage, which allows us to collect a large enough sample of media coverage and conduct a detailed analysis of the major frames employed by the Israeli media. Finally, research on polygamy in Israel has identified two additional frames alongside the securitization and orientalist frames outlined in the previous sections of this paper, namely, a “women’s rights” frame and an “existential threat” frame. These two additional frames have not been explored in the context of Israeli media, but rather in analysis of Israeli state discourse and the work of women’s rights activists and organizations. However, as we show in subsequent sections of this paper, they are relevant in the media context as well regarding the representation of women belonging to a minority Muslim community.

Polygamy is derived from the Greek words polys—many and gamos—marriage (Bozhilova 2018). It means “the practice of multiple marriages,” and is defined as a “marital relationship involving more than one spouse” (Al-Krenawi et al. 2011, p. 594). Polygyny is the marriage of one man to multiple women. Polygamous marriages are present in a variety of societies, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Asia, and in some European and North American countries (Al-Krenawi 2020). Studies suggest several social, cultural, economic, and religious explanations for the historical presence of polygamy in particular societies. First, polygamy is viewed as a symbol of a man’s status—the sign of a man’s economic success (Aburabia 2011). Second, polygamy arises due to the desire to maximize the number of children within a family, which translates into an increase in the labor power and prestige of the household (Ibid.). The third major cause of polygamy is demographic, meaning that there are more women of marriageable age than men, and child mortality rates are high (Ibid.).

However, in the Bedouin community of Israel today, as some studies indicate, social pressure is among the most common cause for men to take more than one wife (Al-Krenawi and Lev-Wiesel 2002; Alhuzail 2022); this is mainly associated with the expectation and desire for a man to conceive multiple sons to expand the family lineage and legacy through reproductive strategy. A man’s ability to produce sons outwardly displays his social status. Infertility, specifically the failure to bear male offspring, and mental or physical illness are all circumstances that are commonly associated with the husband’s decision to take a second and third wife (Dinero 2012; Sinai and Peleg 2021). In some cultural or social contexts, fertility issues or the failure to conceive sons (at times viewed as the same problem) are the woman’s fault (Al-Krenawi 2020). It is also recognized for men to take a second and third wife following the demise of the first wife’s reproductive ability, again linked with social pressures and the affirmation of status and masculinity (Ibid.).

In Israel’s Bedouin community, most polygamous marriages are conducted in private religious ceremonies (Boulos 2021); therefore, there is no official data on the occurrence of polygamous marriages within the Bedouin society. However, research suggests that between 20 to 40 percent of families in the Negev are polygamous (Aburabia 2022; Boulos 2021). In the past three decades, polygamous marriages among Bedouin citizens have advanced at a rate of one percent per year, and this rate continues to increase regardless of age, education, or socio-economic status (Aburabia 2017).

One of the main arguments in feminist research attempting to explain the continuous increase of polygamous marriages among Palestinian Bedouin citizens of Israel highlights the intersection of Israeli colonial power and patriarchal power, which disenfranchises Bedouin women (Aburabia 2011; Boulos 2021). According to this “women’s rights” frame articulated by critical feminist scholars, colonial power is how Israel uses its political hegemony to govern its non-Jewish citizens. Colonial power segregates Bedouin society internally by reinforcing traditional tribal structures and permitting the practice of polygamy to proliferate. Patriarchal power encourages Bedouin men to exercise their authority over women in a hierarchical structure based on gender differences. In short, the “women’s rights” frame sees polygamous marriages as stemming from a complex reality in which Bedouin women suffer intersectional discrimination as women and as members of a marginalized group (Aburabia 2011; Boulos 2021).

Section 176 of the Israeli Criminal Code prohibits the practice of polygamy. Polygamy is a prosecutable criminal offense with a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment; however, the criminalization of polygamy by state law does not undermine its permissibility under Sharia law (Aburabia 2017). Israel’s lack of enforcement of its criminal code prohibiting polygamy has encouraged the practice of polygamy, and according to some interpretations, Bedouin men “channel their frustration and resistance to Israeli domination to the private sphere—toward women” (Aburabia 2011, p. 490). The internal functioning of colonial and patriarchal powers encourages Israel’s legal system to overlook polygamy and thus further marginalize Bedouin women.

According to this intersectional analysis, colonial power intersects with societal norms and pressures, making it difficult for Bedouin women to escape polygamous marriages. Divorcees have limited prospects of remarriage in Bedouin society. The economic dependency of many Bedouin women on their spouses linked with the patriarchal structure of the society and the absence of adequate legal protection further limits women’s ability to resist polygamous marriage (Aburabia 2011, 2021).

Thus, the research has analyzed polygamy within Israel’s Bedouin community as a complex phenomenon resulting from both internal patriarchal reinforcement within Bedouin communities and external discrimination by the Israeli state. The negative effects of polygamy on women, particularly first wives, are well documented, as women experience higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Boulos 2021). Qualitative research reveals that if a man takes a second wife, the first wife experiences severe emotional and psychological trauma. The man often moves to a separate home with his new wife, and the family experiences deep emotional loss, particularly children who lose fathering, attention, love and family coherence (Alhuzail 2022). In part due to limited ways for women to achieve social mobility, marriage, including becoming a second or third wife, is a vehicle to achieve it for women who are deprived of education and economic independence. In abusive contexts, victims are often unable to divorce as it is legally difficult and socially stigmatized to do so, in addition to the likelihood of losing the custody of children and having limited economic opportunities (Boulos 2021).

As stated, Israel has avoided enforcing the law against polygamy, and has framed polygamy as a cultural and religious issue rather than acknowledging the role the state has played in contributing to the disenfranchised and marginalized status of the Bedouin community and the state’s role in perpetuating polygamy. Before the establishment of the state in 1948, Bedouins relied on agriculture and cattle grazing through land ownership to generate income. With the creation of Israel, Bedouin communities were largely displaced and forcibly resettled in localities unsuitable for cultivation. Forced resettlement to areas without adequate employment infrastructure deprived Bedouins of their primary sources of income, and undermined the place of women in the community, who previously farmed the land and raised cattle (Alhuzail 2022; Boulos 2021). Today, Bedouin towns and villages are among the poorest in Israel (Ibid). Unemployment rates among Bedouin men are estimated at 50 percent, and that of Bedouin women at 78 percent (Harel-Shalev and Kook 2021).

While authorities have been reluctant to enforce the polygamy law, matters changed in 2017. Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked, of the far-right party Yamina, decided to establish an inter-ministerial task force on polygamy in that year, declaring a “war” on the practice. Analyses of resulting government discourse and actions on polygamy have identified a particular frame employed by the state—namely an “existential threat” frame (Harel-Shalev and Kook 2021; Boulos 2021). Right-wing government officials began to construct polygamy as a demographic threat which could alter the balance between Jews and Arabs in Israel. This, according to the threat frame, endangers the very existence of Israel as a Jewish state by undermining its Jewish demographic majority. Possibly as a result of this attitude, while the recommendations of Israel’s taskforce on polygamy recognized the vulnerability of women in polygamous marriages, they failed to adequately provide support for victims and instead focused on punitive measures and prevention rather than addressing the current needs of women in existing polygamous marriages (Alhuzail 2022; Boulos 2021).

Harel-Shalev and Kook (2021), who conducted the most comprehensive study of state discourse surrounding the anti-polygamy campaign launched by Shaked, has found two dominant public narratives. First, they identify what we in this paper call the orientalist frame, which rests on the notion that “Muslim Bedouin women are helpless victims, under threat from their own society and in need of the modernizing influence and power of the State of Israel”. (Harel-Shalev and Kook 2021, p. 10). Second, the authors find that another dominant theme that emerged in the public discourse on polygamy was that of demography, “particularly, the impact of increased birthrates resulting from the practice of polygamy on the demographic identity of the State” (p. 10). They argue that the state thus “enforces the distinction between the majority and the minority—between those who belong naturally and those who threaten the natural bonds of membership. By narrating polygamy as a threat to the demographic balance, the State is reinforcing the importance of a demographic balance to its stable identity, while also reinforcing hierarchies of belonging”. (p. 12)

To conclude, the review of the literature fleshed out our four main media frames which we expect to find in the Israeli media’s coverage of polygamy in the Bedouin community. These are: (1) an orientalist frame which blames Muslim religion or culture for women’s oppression and paternalistically constructs the modernizing state as a savior; (2) a securitization frame, which views gendered minority practices, and minority communities as a whole, as endangering the security of majority citizens and of the state; (3) an existential threat frame which considers minority population growth as a demographic threat to the very character, and thus existence, of the state; and (4) a women’s rights frame, stressing the absence of and need for equal citizenship. We proceed in the following section to evaluate whether and in what ways such frames in fact dominate Israeli media discourse on polygamy.

5. Sources and Methods

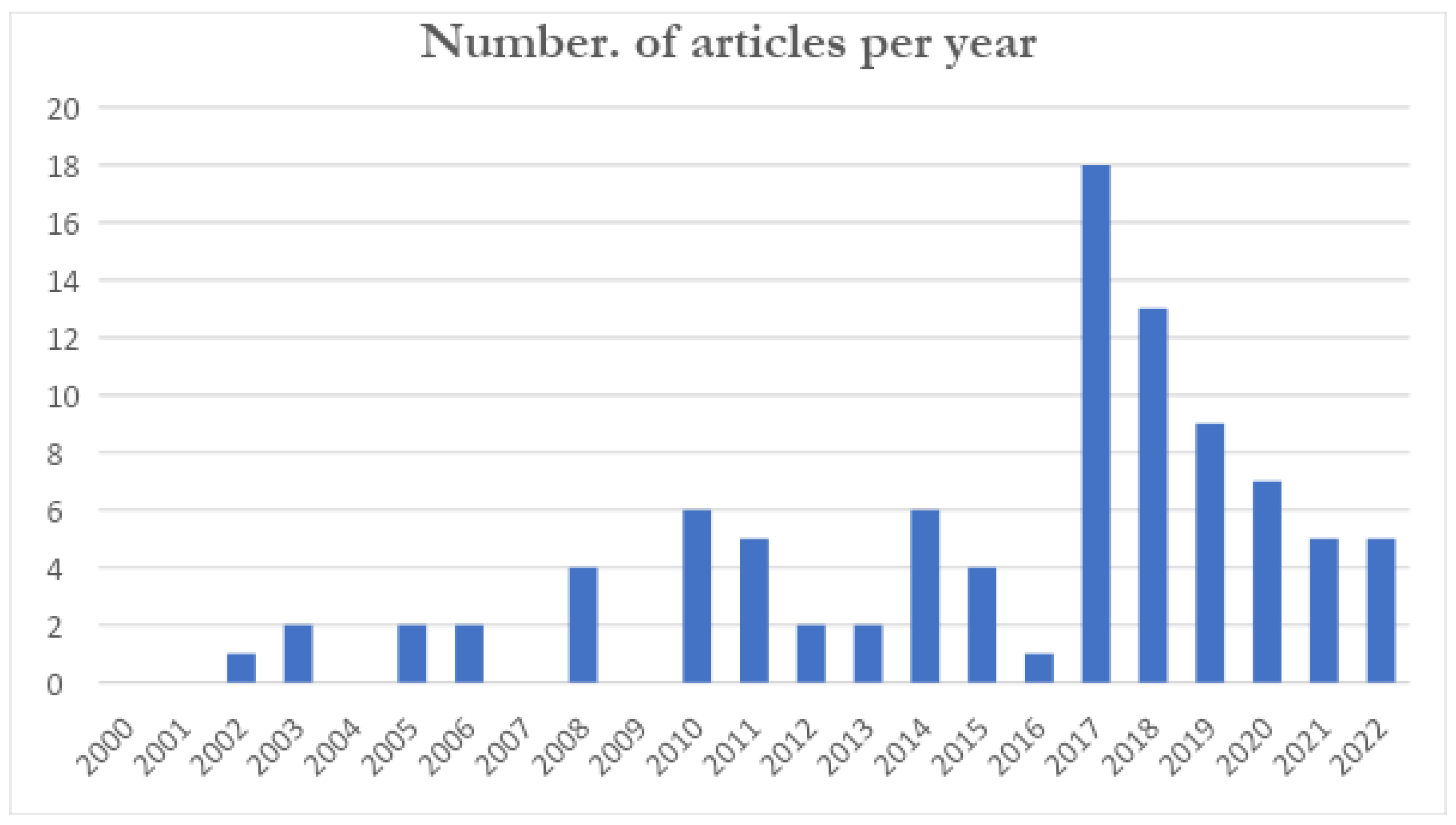

For a cross section of Israeli media, we selected the following four news outlets: Arutz 7 (or INN, Israel National News), a right-wing outlet, associated with Israel’s right-wing settler movement; Haaretz, a left-leaning paper associated with an educated, middle class and upper middle-class readership; and the Jerusalem Post (JP) and Times of Israel (TOI), both currently considered in the center with regard to their political leanings (See Table 1). We chose these outlets as they have clear and stated political orientations, and thus allow us to examine whether and in what way political affiliation affects representation. All of these sources also have a Hebrew and English version, enabling accessibility to a wider audience. We collected all articles about polygamy among the Bedouin citizens of Israel published in these outlets from 2000 to 2022 using a key words search (polygamous, polygamy—poligami, poligamit, poligamiya, in Hebrew) and retrieved 94 articles in total. The majority of articles appeared in Arutz 7 and Haaretz, with a smaller number published in JP and TOI. Not surprisingly, we found an uptick in coverage of polygamy following the decision of then Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked to declare publicly and forcefully a “war on polygamy” in 2017 (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Details on Sources.

Figure 1.

Number of articles on polygamy per year.

We then conducted qualitative content and discourse analyses using the following steps. First, a content analysis via MAXQDA software identified the frequency of all terms (words, phrases) used in each news source. Second, we coded the most frequent terms into themes addressed in the articles. We also determined whether each article sourced state bodies (courts, police, elected officials, etc.), women’s rights activists, organizations, and women in polygamous marriages, or both state and women’s perspectives. Sourcing is important to determine which voices are represented, who is considered an authority on the subject or as news-worthy, and whose understanding of relevant themes is articulated.

Third, we conducted interpretive discourse analysis that read each of the 10 most frequent themes in each news source, within their context within each article to identify the type of use and meaning conveyed by each theme, which we clustered into four frames based on the way themes were used in context. For illustration of the method, we provide extensive examples in our results section. In addition, the database of all articles collected is available from the authors upon request.

6. Results and Analysis

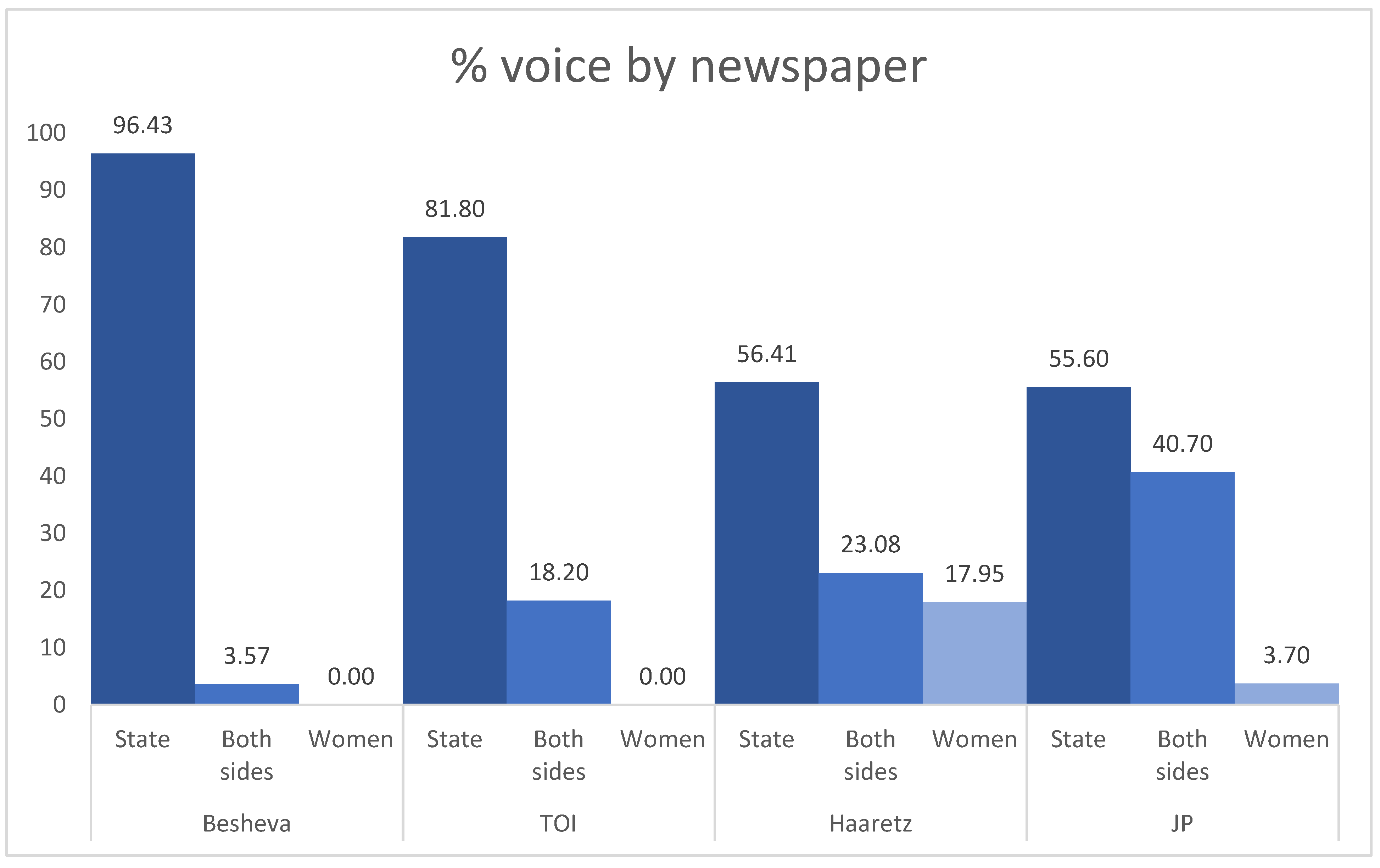

As expected, in all four outlets, the predominant source of information and/or subject of coverage is the state—its policies, actions, discourse, etc. on the question of polygamy among Bedouin citizens. Figure 2 presents our findings, Most striking is Arutz 7, where over 96 precent of articles relied only on state sources or focused only on state policies, actors, and pronouncements. In this outlet, only 3.57 percent of articles included voices from women’s rights activists or women in polygamous situations. No article sourced or focused strictly on women’s rights activists or women in polygamous families. TOI also relies on state voices in over 81 percent of the articles, with only about 18 percent reflecting voices from both state representatives and women’s rights activists. For JP and Haaretz, the state’s voice still leads, with 55.6 percent and 56.4 percent of articles, respectively. They both, however, also bring a significant representation of other voices, with about 23 percent of articles in Haaretz reflecting both state and women’s rights voices, and 17.95 percent delivering women’s perspectives exclusively. For JP, 40.7 percent of articles reflect “both sides,” and only 3.7 percent strictly women’s voices.

Figure 2.

Voice by Newspaper.

Overall, we identified 26 themes addressed in our database of articles. These were coded using the software MAXQDA. Appendix A provides a comparison of the top-10 most frequent codes for each news outlet, meaning the themes that were addressed in the largest number of articles in each of our four sources. Our analysis reveals a clear relation between the political leaning of a news outlet and the type of frames that the outlet uses to represent the phenomenon of polygamy. It is important to note that our discourse analysis meant that we placed the use of each theme in context to explicate its participation in the construction of a particular frame. For example, the theme of “enforcement” could belong to a securitization frame—meaning the need for greater police crackdown and the state’s punitive measures to curb criminality and security threats. Alternatively, “enforcement” could be part of a women’s rights frame, by drawing attention to women’s rights’ organizations’ demand for proper protection of women and an end to the neglect and discrimination of certain marginalized groups, and particularly minority women. Below we discuss our findings for each news source.

Affiliated with the radical right, Arutz 7’s frame is explicitly one of “existential threat”. As Table 2 shows, the two most frequent themes, as they emerge from our coding, are “threat” (appearing in 64.29 percent of articles) and “demography” (60.71 percent of articles). Even the headlines given to articles immediately reveal this framing, with titles such as: “Israeli-Arab polygamy: existential threat”, “Polygamy fueling mass Bedouin illegal immigration to Israel”, and “Send the Bedouin to Libya”. The existential threat frame articulates demographic anxieties. It imagines Bedouin polygamy as a driver of high Muslim birthrates on the one hand, and the “invasion by marriage” of Palestinian Muslims from the West Bank and Gaza, who further add to Muslim population growth in Israel. This is constructed as a threat to the very existence of Israel as a Jewish state, as it is said to undermine its Jewish demographic majority.

Table 2.

Arutz 7.

The following quotes provide illustrations of this discursive frame. For example, “Israel is hoping to hold down the explosive growth of the Bedouin population by regulating polygamy”.4 Another example, “The blind-eye turned to Bedouin polygamy also has serious demographic repercussions for southern Israel. With a natural growth rate of 5.5%, the Bedouin community in the Negev doubles roughly every 13 years…This growth comes in part from the large number of women who immigrate illegally to Israel to marry Bedouin men, often as the second, third, or even fourth wife…20,000 women from the Palestinian Authority alone currently reside illegally in Israel and are married to Israeli Arab men. In addition, some 8000 children born to foreign mothers without legal status reside in Israel illegally…”5 The link to an existential threat is articulated quite explicitly in Arutz 7. For example: “This wave of immigration is very dangerous to Israel’s national security, presenting a security, criminal, and political danger, an economic burden, and especially a demographic danger for the future of the State”.6 And, “Aside from the victims themselves—the women and children in the Negev who suffer directly from this phenomenon—the price of polygamy has been paid by all of Israeli society for far too long…not to mention the far-reaching social and demographic ramifications that cast a shadow over the future of the State of Israel”.7

In addition, the securitization frame is also present, although secondary, in Arutz 7’s representation. The themes of “enforcement” (28.57 percent of articles), “crime” (21.43), “terrorism” (21.43) and “violence” (17.86) usually refer not to the harm inflicted on women in polygamous contexts, but rather the security harm to the state. For example, “The Bedouin population in the Negev, aided by Israel’s relaxation of laws against polygamy in favor of Bedouins, has shot up…[I]increasingly larger numbers of potential [Bedouin] soldiers have begun rejecting volunteering for the army, preferring to cooperate with Hamas terrorists to steal and smuggle weapons and to attack Jews”.8 Or: “We cannot ignore the fact that the terrorists who were arrested in this incident are products of the practice of polygamy in the Bedouin sector…In order to make it possible for Bedouin men to take a second, third or even fourth wife, a massive ‘import-export trade’ has burgeoned in the Negev. The brothers arrested today…are products of a polygamous household, and the connection to hostile groups is built into the family connection to Gaza”.9 Finally, the theme of “welfare”, which might express attention to socio-economic deprivation, discrimination, and women’s well-being, is in fact contextualized in Arutz 7’s discourse within the “securitization” frame, emphasizing what it considers the “welfare fraud” perpetrated by polygamous Muslims, “massive social welfare payments and widespread fraud have cost the Israeli taxpayer billions…”10 Or “the Ministry of Justice has issued a firm line on the issue of polygamy. Last month, a memorandum of law was published…which seeks to impose economic sanctions on Bedouin women who declare themselves fraudulently as ‘single mothers’ but are, in fact, married”.11

Similarly, the theme of “religion” is not framed so much within the orientalist modernization frame, which seeks to “save” Muslim women from the alleged oppression of their religion and culture. Rather, it is also a part of the securitization frame which views Islam through the prism of radicalism and violence, as well as the existential threat frame concerned about Muslim demographic growth. For example, consider the following quotes: “Be’er Sheva and the surrounding area is a hotbed for radical Muslims, encouraged by the surging Bedouin population as the result of polygamy, outlawed in Israel but allowed for Bedouin as a “religious tradition”. Thousands of women who marry Bedouin men are from Gaza, Judea, and Samaria and even from Arab countries, particularly Jordan. Hamas has a stronghold in the adjacent Bedouin neighborhood of Tel Sheva, where police avoid entering out of fear of violence”.12 Or “Bedouin leaders have publicly stated that Bedouin men are encouraged to marry more than one woman in order to leave the Jewish population in the minority and not because of religious or traditional reasons”.13

The Haaretz newspaper furnishes greater space for Arab and Bedouin women’s perspectives on the issue of polygamy, with close to 18 percent of articles relying exclusively on women’s perspectives, significantly more than the other three news outlets combined. About 23 percent of articles bring both the state and women’s voices. In addition, although over 56 percent of articles focus only on the state and source only state representatives, many of these are critical of state policies and actions rather than simply neutral or supportive. Thus, the dominant frame that emerges in Haaretz coverage is one focused on women’s rights to equal citizenship and equal well-being. As Table 3 demonstrates, The themes of “enforcement” (56.41 percent of articles) chronicles the state’s actions and failure to enforce the ban on polygamy, but also voices Bedouin and Arab women activists’ criticism of the state’s discrimination and failure to guarantee equal rights for women, to which all citizens should be entitled. For example, in an interview with Insaf Abu Shareb, a women’s rights activist on polygamy, the themes of “enforcement” (56.41 percent of articles) and “demography” (20.51) come up, but from a critical, women-centered perspective. “How is it possible that until now the State of Israel, in which this terrible phenomenon flourishes, has not done anything significant to curb polygamy? The state enters the struggle against polygamy only when [polygamy] threatens its interests as a state, meaning when it is a part of the demographic threat. Otherwise, Bedouin women do not interest [the state]. Polygamy pulls the Bedouin society down. I see it as a part of the [state’s] policy”.14

Table 3.

Haaretz.

Constituting the women’s rights frame is attention to “harm” to women and children in polygamous marriages, the attendant questions of “rights” (41.04 percent), “equality”, (17.95) intersectional “discrimination” (17.95) by the state of women from a minority community, criticism of the state’s “denial of citizenship”, and recognition of the state’s disenfranchisement of “Palestinians” (43.59). In addition, both in analyzing the causes for polygamy, as well as effective strategies to address it, “enforcement” is accompanied by stress on “education,” (48.72) and “employment” (17.95). The theme of “religion”, (33.3) which is prevalent in Haaretz, is not addressed through an orientalist frame that sees Islam as the root cause of women’s oppression. Rather, it is often mentioned as part of the critique of state institutions, particularly state Sharia courts, in their failure to guarantee the rights of Muslim women as stipulated by Islamic law. For example, “Sharia courts, working under the Justice Ministry, continue to recognize polygamous marriages after the fact, and thus lead the way to their recognition, even though they are conducted against the law. The Justice Ministry is aware of this but argues that it cannot instruct the courts to deny recognition, despite the Ministry’s legal authority over the courts”.15 It is important to acknowledge that the preponderance of Haaretz coverage of the state, at times simply through reporting rather than with an added critical lens, allows for the state’s narrative about, for example, the need for punitive enforcement, welfare fraud crackdown, and “rescuing” Bedouin women from their oppression, ample space for articulation. However, mitigating this fact is the close to equal space the newspaper affords to critical voices, especially Arab and Bedouin women’s rights activists.

The Jerusalem Post’s coverage is a mixed bag, as reflected in Table 4. On the one hand, it brings women’s perspectives and women’s rights activists’ perspectives (the theme of “rights” appears in 68.75 percent of articles), as well as addressing issues such as harm to women (50 percent of articles, domestic violence 43.75), socio-economic aspects of polygamy (poverty 43.7) and non-punitive measures for prevention and remediation (employment 43.7, education 68.75). On the other hand, it features a preponderance of culturalist explanations, aligning its narrative with the orientalist frame which sees challenges to women’s rights as a fault of Arab and Muslim culture. Significantly, however, its discourse does not fault religion for the problem of polygamy. Articles often mention that Islam permits polygamy only if the wives are treated equally, and focus on the bureaucratic issue of Sharia courts, rather than simply on Islam as a religion. Yet culturalist arguments abound in the articles. For example:

Table 4.

Jerusalem Post.

“‘It’s been difficult to enforce the [polygamy] law, because we’re talking about a traditional society which for decades has carried on with their daily lives without [outside intervention],’ Justice Ministry director-general Emi Palmor, who headed a committee that published an extensive report on the matter”.16

“[I]n most Arab societies the phenomenon is frowned upon and in Israel polygamy is illegal, punishable by up to five years in prison. Nevertheless, the custom is deeply rooted in the culture of the Bedouin Arabs who traditionally were tent-dwelling nomads but who have gradually been settled in permanent towns like Rahat”.17

“My husband justified the marriage by saying he needed a woman at home,” she says. “In Bedouin culture, a woman is like a car. If it needs repairs, just get a new car”.18

“Throughout the Middle East [the Bedouin] pose the classic clash between urban order and traditional nomads who claim a right to wander where they will, live as they wish, and support themselves with whatever activity is available”.19

“[T]here are still serious problems between the state and the Bedouins, and deeper—because all of these differences stem from the tremendous gaps between the Bedouin culture and a state culture”.20

“Historically, while the country’s Jewish majority, governed by more modern and secular democratic principles, frowns on the practice, it has been hesitant to risk a culture war with the Bedouin minority, preferring to mostly let Bedouin govern themselves”.21

“Another cultural matter related to Bedouins is the matter of honor killing and blood feuds”.22

The combination of harm to women and their rights together with explicit stereotyping of Bedouin culture leads to a dominant orientalist frame which implies that Bedouin society must be modernized, in this case by the modern Jewish state, and that Bedouin women’s rights entail their liberation from their own oppressive culture.

Table 5 shows results for the Times of Israel. It is more difficult to reach a conclusive view of the Times of Israel’s framing of polygamy, largely because the paper was only launched in 2012 and because it has published the smallest number of articles on the subject in comparison to all the other outlets considered here. Many of the major themes that we found in our review of the paper are often simply straightforward reporting, usually on government and state sources. Thus, the theme of enforcement covers the state’s pronouncements on its intentions to increase enforcement of the polygamy ban, the theme of welfare covers the state’s intention to recruit welfare authorities to help women in polygamous situations, and the problems of the status of such women in their registration for social security (as “single mothers” or as members of “enlarged families”).

Table 5.

Times of Israel.

The clearest example of this reporting, which withholds editorial commentary, is on the theme of demography. While it appears relatively frequently, it is invoked as simply reporting of state officials’ words—for example: “TV report says Netanyahu warned of Bedouin growth as existential threat” and “‘This is a violation of the status of women, exploitation of women, and also undermines the demographic balance in Israel by importing wives,’ [Netanyahu] tweeted”.23 However, it also appears in coverage of critical views of the state’s demographic discourse by Bedouin activists—for instance: “Arab feminists fear Israel’s anti-polygamy plan is opening volley in a war of wombs”;24 “Both Bedouin opponents and proponents of polygamy are deeply skeptical or outright reject the plan, which is being spearheaded by Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked, arguing that it is really aimed at decreasing the high Bedouin fertility rate, and thereby, ensure a Jewish majority in the Negev desert, where most Bedouin live”;25 “Abu Shareb (an Arab women’s rights activist) believes it is numbers that may drive the Israeli government to enforce the anti-polygamy law in a bid to bring down the Bedouin sector’s high birthrate. ‘It will come from a place of demographic fear about the growth of Bedouin society, not the welfare of Bedouin society,’ she said”.26

The only frame we can more definitively identify is, as in the case of the JP, the orientalist, culturalist frame, which highlights Muslim religion and culture as an underlying cause of women’s oppression. Unlike the JP, which often separates religion from culture, assigning blame for polygamy to Bedouin culture and not to the Muslim religion, the TOI often conflates the two. For example:

“The meeting discussed widespread polygamy among the Bedouin, who are a conservativeMuslim community concentrated in the northern Negev desert and in northern Israel”.27

“[Polygamy is] a deep-rooted cultural and religious practice, primarily found among Israel’s Bedouin communities”.28

“Traditional Islam allows for a man to marry at maximum four wives at a time…”29

“Israel Police has also been reluctant to intervene in what is perceived as a deep-rooted cultural and religious practice, primarily found among the Bedouin”.30

“Polygamy is permitted in the Quran, which allows up to four wives, especially in cases where the wife is sick, infertile, or failing to produce sons”.31

“The notion of regulating the community’s marital practices is extremely contentious, as polygamy is permitted in traditional interpretations of Islam and widely practiced among members of Israeli Bedouin society”.32

“The Israeli Police has also displayed reluctance to intervene in what is perceived as a deep-rooted cultural and religious practice…”33

Although TOI does not publish a fair number of Bedouin and Arab women’s rights activists’ viewpoints, the importance of their voices can be gleaned in the following quote from a women’s rights activist on the question of “culture,” that the paper does include: “It…makes her furious when authorities or organizations decline to intervene by citing cultural sensitivity to Bedouin culture. “When people say, ‘Oh, it’s too sensitive,’ I say, ‘What about domestic violence or rape? Do you consider that too culturally sensitive to get involved?’”34

7. Analysis and Discussion

As our findings demonstrate, there are four frames which emerge in the Israeli media coverage of polygamy among Israel’s Bedouin citizens. However, significant nuances also emerge. First, coverage is to a large extent shaped by the political affiliation of the news outlet. Thus, readers of the more left-leaning Haaretz will be exposed to a multilayered discourse that also features Bedouin women’s perspectives, the voices of Arab and Bedouin women’s rights activists, a contextualization of the problem within its socio-economic and political causes, and the placing of this minority practice within a discussion about the equal right to citizenship for women and for members of disenfranchised communities.

Readers of the far-right Arutz 7 will be exposed to an explicit existential threat frame, which views Bedouin women’s issues only through the prism of a xenophobic articulation of the national interests of the Jewish majority that considers Muslim women’s wombs as a demographic weapon in a battle between Jews and Muslims in Israel. Anxieties about “illegal immigration”, terrorism, lawlessness, and crime are also linked tightly in Arutz 7’s discourse on the issue of polygamy, combining the existential threat frame with a securitization frame. While this narrative is strongly associated with the official narrative of the state, Arutz 7 goes even further, criticizing the state for not being tough enough in the face of what it considers to be a grave threat to the national body.

For the two centrist news outlets we reviewed, a more mixed picture emerges, in part due to the smaller amount of coverage of the issue of polygamy. On the one hand, since coverage is often state-centered, the themes that emerge usually amplify the state’s narrative, even in the absence of editorial commentary by journalists themselves. In addition, in both JP and TOI, the orientalist frame is starkly present, with many articles repeating negative stereotypes about Bedouin culture and suggestions that culture is the root cause of women’s oppression through practices like polygamy (although while TOI conflates religion and culture, JP makes a distinction between the two regarding the issue of polygamy). On the other hand, the importance of Bedouin and Arab women activists’ voices in making a dent in culturalist frames is starkly revealed in our analysis. In both JP and TOI, the inclusion of these voices, (even if to lesser degrees than voices of the state) helps to complicate the representation of the phenomenon, offer critical perspective and political analysis, and, importantly, portray women from minority communities as fearless agents rather than passive victims in need of saving by the modern state.

In sum, our findings demonstrate the extent to which sources and voices are crucial for media frame constructions, and consequently to public perception of minority communities. First, the political leanings of news sources, not surprisingly, determine the type of frames employed, especially on the left and right. Second, in all news sources we see that the agenda on issues of minority women’s rights is set largely by the state in terms of attention. While the problem of polygamy has been one that Bedouin women activists have been fighting against for over two decades, it is only when the state decided in 2017 to turn its full attention to the matter that media coverage of the phenomenon picked up steam. In addition, all our news sources tend to source state bodies, officials, policies, and actions more than other actors—such as Bedouin and Arab women’s rights organizations and Bedouin women in polygamous marriages. However, when the latter are given voice in coverage, the framing of women’s rights within a minority community receives more nuance. It tends to add critical perspectives on the state’s narratives and an emphasis on women’s right to equal citizenship, which minority women demand from the state, rather than portraying minority women as passive victims oppressed by their own culture or religion and in need of saving by the state.

8. Conclusions

The findings presented outline the prevalence of four frames in Israeli media coverage of polygamy among Israel’s Bedouin citizens. Three of the four frames endorse negative and inaccurate perceptions of Bedouin Muslim women and ultimately reinforce racial and gender stereotypes and discrimination. These dominant media frames have important implications for public perceptions of Bedouin Muslim women. As we outlined in our literature review, media frames can have a detrimental impact on the majority views about minority groups. When dominant media frames portray a minority group in a negative light, blame its members for the community’s challenges, and exaggerate the problem a minority group constitutes for the majority, the likelihood of true engagement with the needs and challenges of the minority could be greatly diminished. The results of our research not only reveal the skewed and largely one-sided representation of Muslim minority women and their issues, but also demonstrates how platforms given to the voices of minority groups remain limited. Previous research argues that Muslim minorities are often stereotyped and vilified in other non-Muslim majority countries too, not just in Israel. As anti-Muslim and Islamophobic sentiments in Western media continue, further research should examine how culturally specific gendered practices of Muslim minorities are grappled with by the media in other non-Muslim majority countries to enrich current findings. Additionally, amplifying the voices of Bedouin and Muslim women and their own analysis of the problem of polygamous marriage in Israel and in other non-Muslim majority countries would provide a deeper understanding of the perspectives of women in these communities, those of women in polygamous marriages, and those committed to minority women’s rights and equal citizenship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; methodology, L.B.S.; software, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; validation, L.B.S.; formal analysis, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; investigation, S.A.K. and A.P.; resources, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; data curation, S.A.K. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; visualization, L.B.S., S.A.K. and A.P.; supervision, L.B.S.; project administration, L.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Comprehensive list of the top-10 themes in all four newspapers’ articles on polygamy, comparing the frequency of their appearance in each source.

Table A1.

Themes and frequency.

Table A1.

Themes and frequency.

| Top 10 Themes | Times of Israel | Jerusalem Post | Arutz 7 | Haaretz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| welfare | 63.64 | 50.00 | 35.71 | 48.72 |

| religion | 63.64 | 62.50 | 32.14 | 33.33 |

| harm (women and children) | 36.36 | 50.00 | 14.29 | 38.46 |

| enforcement | 81.82 | 75.00 | 28.57 | 56.41 |

| education | 63.64 | 68.75 | 14.29 | 48.72 |

| violence | 54.55 | 43.75 | 17.86 | 12.82 |

| demography | 54.55 | 31.25 | 60.71 | 20.51 |

| rights | 27.27 | 68.75 | 14.29 | 41.03 |

| threat | 36.36 | 6.25 | 64.29 | 5.13 |

| poverty | 36.36 | 43.75 | 3.57 | 15.38 |

| Palestinians | 54.55 | 12.50 | 7.14 | 43.59 |

| employment | 18.18 | 43.75 | 10.71 | 17.95 |

| discrimination | 36.36 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 17.95 |

| culture | 45.45 | 56.25 | 3.57 | 12.82 |

| crime | 9.09 | 43.75 | 21.43 | 15.38 |

| terrorism | 9.09 | 0.00 | 21.43 | 5.13 |

| Regavim | 0.00 | 6.25 | 25.00 | 15.38 |

| health | 45.45 | 12.50 | 7.14 | 10.26 |

| equality | 27.27 | 37.50 | 0.00 | 17.95 |

| citizenship–denial | 9.09 | 0.00 | 10.71 | 20.51 |

Notes

| 1 | Importantly, this paper concerns Palestinian Bedouin citizens of the state of Israel, not Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza who are non-citizens. |

| 2 | To foreshadow our discussion of method in the Sources and Methods section, we note here that content analysis via MAXQDA software identified the most frequent terms (words or phrases) used in each news source and their frequency. We coded the 10-most frequent themes that emerged from the quantitative analysis in each news source. Next, an interpretive discourse analysis which read each theme within its context within each article identified the type of use and meaning conveyed by the theme, which we clustered into four frames based on the way themes were used in their contexts. For illustration of the method, we provide extensive examples in our results section, In addition, the database of all articles collected is available from the authors upon request. |

| 3 | Regavim is a far-right, anti-minority organization targeting mainly the Bedouin population, as well as other minorities in Israel and the West Bank. |

| 4 | Levi, Yaakov. “Minister: Regulate Polygamy to Slow Bedouin Growth”. Artuz 7, 29 September 2014. |

| 5 | Rosenberg, David. “Polygamy fueling mass Bedouin illegal immigration into Israel”. Artuz 7, 11 January 2017. |

| 6 | Arutz 7 Staff. “Israeli-Arab Polygamy: Existential Threat”. Artuz 7, 6 February 2003. |

| 7 | Arutz 7 Staff. “Regavim blocks attempts to create legal ‘back door’ for polygamy”. Artuz 7, 8 October 2018. |

| 8 | Ben Gedalyahu, Tvi. “Send the Bedouin to Libya”. Artuz 7, 27 April 2011. |

| 9 | Sones, Mordechai. “Polygamy in Bedouin sector: Ticking time-bomb that nearly exploded”. Artuz 7, 7 September 2020. |

| 10 | Arutz 7 Staff. “Regavim blocks attempts to create legal ‘back door’ for polygamy”. Artuz 7, 8 October 2018. |

| 11 | Arutz 7 Staff. “Bedouin council head: ‘I support polygamy, religion above law’”. Artuz 7, 20 November 2018. |

| 12 | Ben Gedalyahu, Tzvi. “Muslim Leader Preaches Jihad in Be’er Sheva”. Artuz 7, 9 October 2012. |

| 13 | Ben Gedalyahu, Tzvi. Bedouin Intifada”. Artuz 7, 7 November 2010. |

| 14 | Litman, Shani “Will anyone deal with the phenomenon of polygamy in the Bedouin community? Haaretz, 19 January 2017. |

| 15 | Ben Zikri, Almog. “Under the auspices of the Justice Ministry, Muslim courts legitimate polygamy. Haaretz, 7 July 2019. |

| 16 | Maya Margit, “Bedouin women strive for equality and to end polygamy in Israel”, The Jerusalem Post, 3 November 2018. |

| 17 | David Miller, “Israeli anti-polygamy activists run into Islamic opposition”, The Jerusalem Post, 23 December 2010, 2. |

| 18 | Linda Gradstein, “Marriage of convenience,” The Jerusalem Post, 27 December 2017. |

| 19 | Ira Sharkansky, “Strong state/Lazy state,” The Jerusalem Post, 4 December 2013. |

| 20 | Mordechai Kedar, “The bedoin problem and the only possible solution”, The Jerusalem Post, 13 December 2013. |

| 21 | Yonah Bob, “What is Israel’s position on polygamy?” The Jerusalem Post, 4 July 2018. |

| 22 | Mordechai Kedar, “The Bedouin problem and the only possible solution”, The Jerusalem Post, 13 December 2013. |

| 23 | TOI Staff. “PM Vows Zero Tolerance for Polygamy despite Widespread Flouting of Law”. The Times of Israel, 10 July 2018. |

| 24 | Newman, Marissa. “Arab Feminists Fear Israel’s Anti-Polygamy Plan Is Opening Volley in a War of Wombs”. The Times of Israel, 17 February 2017. |

| 25 | Lieber, Dov, and Video Luke Tress. 2017. “Israel Tries to Save Bedouin from Polygamy, but Finds Little Love for Plan”. The Times of Israel, 18 November 2017. |

| 26 | Lidman, Melanie. “Polygamy Is Illegal in Israel. So Why Is It Allowed to Flourish among Negev Bedouin?” The Times of Israel, 16 February 2016. |

| 27 | TOI Staff. “TV Report Says Netanyahu Warned of Bedouin Growth as ‘Existential Threat”. The Times of Israel, 21 June 2017. |

| 28 | TOI Staff. “In Rare Case, Prosecutors Charge Bedouin Man with Polygamy”. The Times of Israel, 3 October 2017. |

| 29 | Lieber, Dov, and Luke Tress. “Israel Tries to Save Bedouin from Polygamy but Finds Little Love for Plan”. The Times of Israel, 18 November 2017. |

| 30 | TOI Staff. “In Rare Case, Prosecutors Charge Bedouin Man with Polygamy”. The Times of Israel, 3 October 2017. |

| 31 | Lidman, Melanie. “Polygamy Is Illegal in Israel. So Why Is It Allowed to Flourish among Negev Bedouin?” The Times of Israel, 16 February 2016. |

| 32 | Jalil, Justin. “To up Bedouin Living Standards, Minister Tackles Birth Rate”. The Times of Israel, 29 September 2014. |

| 33 | Newman, Marissa. “Ministers Back Welfare, Education Plan to ‘Eradicate’ Polygamy”. The Times of Israel, 29 January 2017. |

| 34 | Lidman, Melanie. “Polygamy Is Illegal in Israel. So Why Is It Allowed to Flourish among Negev Bedouin?” The Times of Israel, 16 February 2016. |

References

- Abu-Guider, Aref. 2018. Media Representations of the Arab-Bedouin Minority within the Green Line in Israel from Young Arabs’ Perspectives. Revue Européenne des Études Hébraïques 31: 144–73. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2002. Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others. American Anthropologist 104: 783–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2013. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aburabia, Rawia. 2011. Redefining Polygamy Among the Palestinian Bedouins in Israel: Colonialism, Patriarchy, and Resistance. Social Policy 19: 36. [Google Scholar]

- Aburabia, Rawia. 2017. Trapped Between National Boundaries and Patriarchal Structures: Palestinian Bedouin Women and Polygamous Marriage in Israel. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 48: 339–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburabia, Rawia. 2022. The Law on the Books Versus the Law in Action: Muslim Women in Polygamous Marriages under the Jewish State. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 29: 634–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. Media Representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A Meta-Analysis. International Communication Gazette 79: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Leila. 1992. Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Saifuddin. 2012. Media Portrayals of Muslims and Islam and Their Influence on Adolescent Attitude: An Empirical Study from India. Journal of Arab & Muslim Media Research 5: 279–306. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hejin, Bandar. 2015. Covering Muslim Women: Semantic Macrostructures in BBC News. Discourse & Communication 9: 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Alhuzail, Nuzha Allassad. 2022. ‘I Wish He Were Dead.’ The Experience of Loss among Young Arab-Bedouin Women in Polygamous Families. Affilia 38: 08861099221075899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, Alean, and Rachel Lev-Wiesel. 2002. Wife Abuse Among Polygamous and Monogamous Bedouin-Arab Families. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 36: 151–65. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Krenawi, Alean, John R. Graham, and Fakir Al Gharaibeh. 2011. A Comparison Study of Psychological, Family Function Marital and Life Satisfactions of Polygamous and Monogamous Women in Jordan. Community Mental Health Journal 47: 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, Alean. 2020. Polygamous Marriages: An Arab-Islamic Perspective. In Couple Relationships in a Global Context, European Family Therapy Association Series. Edited by Angela Abela, Sue Vella and Suzanne Piscopo. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Abeer. 2006. Minorities, Law, and the Media: The Arab Minority in the Israeli Media. Adalah’s Newsletter 30: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, and Tony McEnery. 2013. Discourse Analysis and Media Attitudes: The Representation of Islam in the British Press. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boulos, Sonia. 2021. National Interests Versus Women’s Rights: The Case of Polygamy Among the Bedouin Community in Israel. Women & Criminal Justice 31: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bozhilova, Mariam. 2018. Difference between Polygamy and Polygyny. Difference between Similar Terms and Objects. Available online: http://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/culture-miscellaneous/difference-between-polygamy-and-polygyny/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Brown, Malcolm D. 2006. Comparative Analysis of Mainstream Discourses, Media Narratives and Representations of Islam in Britain and France Prior to 9/11. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 26: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Jennings, and Mary Beth Oliver. 2009. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 3rd ed. New York: Taylor & Francis, p. 657. [Google Scholar]

- Byng, Michelle D. 2010. Symbolically Muslim: Media, Hijab, and the West. Critical Sociology 36: 109–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Enny, Brad J. Bushman, Marieke D. Bezemer, Peter Kerkhof, and Ivar E. Vermeulen. 2009. How Terrorism News Reports Increase Prejudice against Outgroups: A Terror Management Account. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45: 453–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgeer, Shugofa, and Peter J. Gade. 2016. Visual Framing of Muslim Women in the Arab Spring: Prominent, Active, and Visible. International Communication Gazette 78: 432–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinero, Steven C. 2012. Neo-Polygamous Activity among the Bedouin of the Negev, Israel: Dysfunction, Adaptation—Or Both? Journal of Comparative Family Studies 43: 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrkamp, Patricia. 2010. The Limits of Multicultural Tolerance? Liberal Democracy and Media Portrayals of Muslim Migrant Women in Germany. Space and Polity 14: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Aswad, el-Sayed. 2013. Images of Muslims in WesternWestern Scholarship and Media after 9/11. Digest of Middle East Studies 22: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamel, Chouki. 2002. Muslim Diaspora in WesternWestern Europe: The Islamic Headscarf (Hijab), the Media and Muslims’ Integration in France. Citizenship Studies 6: 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, Sara R. 2017. In the name of women’s rights. In The Name of Women’s Rights. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gribiea, Adnan, Mustafa Kabha, and Ismael Abu-Saad. 2017. New Mass Communication Media and the Identity of Negev Bedouin Arab Youth in Israel: In Conversation with Edward Said. Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies 16: 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel-Shalev, Ayelet, and Rebecca Kook. 2021. Ontological security, trauma and violence, and the protection of women: Polygamy among minority communities. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbani, Aparna, and Charise-Rose Wills. 2012. How Muslim Women in Australia Navigate through Media (Mis)Representations of Hijab/Burqa. Australian Journal of Communication 39: 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Erika Katherine. 2019. The Priming of Arab-Israeli Stereotypes: How News Stories May Enhance or Inhibit Audience Stereotypes. Journal of International Women’s Studies 20: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkan, Kerem Ozan, Geoffrey C. Layman, and Eric M. Uslaner. 2009. ‘Bands of Others’? Attitudes toward Muslims in Contemporary American Society. The Journal of Politics 71: 847–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, Douglas. 2004. Spectacles of Terror, and Media Manipulation. Critical Discourse Studies 1: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, Elisabeth, and Susanne Kassel. 2005. The Veil as a Means of Legitimization: An Analysis of the Interconnectedness of Gender, Media and War. Journalism 6: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, Hagar. 2010. The Giver of Life and the Griever of Death: Women in the Israeli TV Coverage of the Second Lebanon War (2006). Communication, Culture & Critique 3: 242–69. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Myra. 2006. Muslim Women and the Veil. Feminist Media Studies 6: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, Vera. 2012. The ‘Afghan Girls’: Media Representations and Frames of War. Continuum 26: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, Dana, and Riva Tukachinsky. 2012. The Influence of Media Exposure on the Formation, Activation, and Application of Racial/Ethnic Stereotypes. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1984. Under Western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Boundary 2: 333–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 2003. “Under western eyes” revisited: Feminist solidarity through anticapitalist struggles. Signs: Journal of Women in culture and Society 28: 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa-Awad, Zahra, and Monika Kirner-Ludwig. 2017. Arab Women in News Headlines during the Arab Spring: Image and Perception in Germany. Discourse & Communication 11: 515–38. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, Laura. 2010. Islamophobia and Sexism: Muslim Women in the WesternWestern Mass Media. Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 8: 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, Kristine A. 1993. Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics. Marquette Law Review 77: 385. [Google Scholar]

- Posetti, Julie. 2010. Jihad Sheilas or Media Martyrs?: Muslim Women and the Australian Media. Paper presented at the Second World Journalism Education Congress (WJEC 2010), Grahamstown, South Africa, July 5–7; pp. 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Kimberly A. 2011. Framing Islam: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism Since 9/11. Communication Studies 62: 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynting, Scott, and Barbara Perry. 2007. Climates of Hate: Media and State Inspired Victimisation of Muslims in Canada and Australia since 9/11. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 19: 151–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Bushra H. 2012. Framing of Pakistani Muslim Women in International Media: Muslim Feminist’s Perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Research 2: 106–13. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Piers. 2001. Theorizing the Influence of Media on World Politics: Models of Media Influence on Foreign Policy. European Journal of Communication 16: 523–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Amir. 2007. Media, Racism and Islamophobia: The Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Media. Sociology Compass 1: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Muniba, Sara Prot, Craig A. Anderson, and Anthony F. Lemieux. 2017. Exposure to Muslims in Media and Support for Public Policies Harming Muslims. Communication Research 44: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinai, Mirit, and Ora Peleg. 2021. Marital Interactions and Experiences of Women Living in Polygamy: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Psychology 56: 361–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shomron, Baruch, and Amit M. Schejter. 2020. The Communication Rights of Palestinian Israelis Understood Through the Capabilities Approach. International Journal of Communication 14: 19. [Google Scholar]

- Sotsky, Jennifer. 2013. They Call Me Muslim: Muslim Women in the Media through and beyond the Veil. Feminist Media Studies 13: 791–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, Carol A., and Deepa Kumar. 2005. Unveiling Imperialism: Media, Gender and the War on Afghanistan. Media, Culture & Society 27: 765–82. [Google Scholar]

- Terman, Rochelle. 2017. Islamophobia and Media Portrayals of Muslim Women: A Computational Text Analysis of US News Coverage. International Studies Quarterly 61: 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Milly. 2014. The British Media, the Veil and the Limits of Freedom. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 7: 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).