Posthumous Release for Lay Women in Tang China: Two Cases from the Longmen Grottoes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

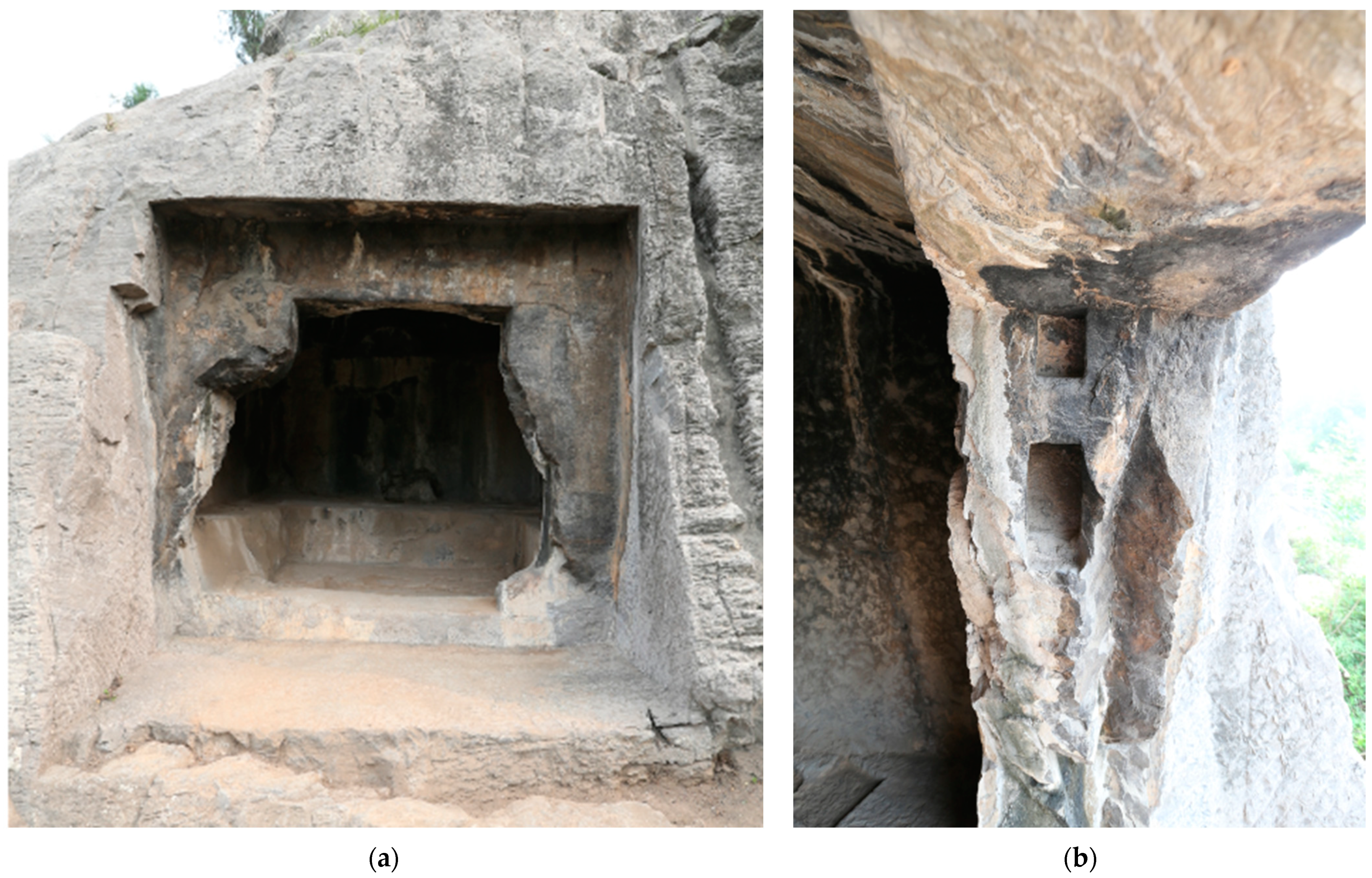

2. Burial Cave of Lady Lou: The “Rule of Śītavana” without Flesh Offering

In the first year of Longshuo reign of the Great Tang, on the twenty-third day of the eleventh month (December 19, 661), Gentleman-litterateur Shen Li (or Shen Pou), for his late wife née Lou, respectfully dedicated a shrine of King Udayana image. I (Shen) document this event with words and have them inscribed as follows.Look, [to enter] the Ultimate Way, there is no [set] path; know that the Way is unpredictable. [To express] the Ultimate Word, there is no words; such is the mysterious tenet of subtle words. Words rely on the Way to express, and the Way rises from words. The Way gains its name from words, and words depend on the Way to manifest virtues. Thus [one] knows that [to distinguish between] the Dharma and unrighteous practices, śarīra performs the origin of the inexhaustible; [to show] small and large forms, Guanyin manifests his divine power.Lou had planted her roots of virtue and kindled her pure mind from early on. [Realizing] the illusion of perception was truly illusional was her pivotal [breakthrough]. [Knowing] that the external body was not [the true] body was her beginning [on the path to enlightenment]. [She] valued the One Dharma more than the weight of mountains and disregarded a thousand gold as if [they were] goose feathers. [She] disliked the contemporaneous custom of funerary, which fills underground tombs with delicate carvings. Admiring the inclinations of the wise men of old, [she would] quietly allow her remains to return to the elements in the wilderness. In the twelfth month of the fifth year (661) of Xianqing reign, when [Lou] fell ill in her home in Sigong [Ward in Luoyang], she mumbled to [Shen] Li that “when I came of age, [I] pledged to grow old together [with you]. [Yet who] could have expected that [my fate] was not blessed, and that I would be succumbed to chronic illness? After I die, I ask that you follow my will”.On the twenty-eighth day of the same month, [Lou] passed away at home. Then [Shen Li] called forth monks and invited the Buddha [image], established a dharma platform to release the soul of the deceased. Offerings were set up and incense was presented. [The service] lasted without interruption for the forty-nine-day period. The date and time [of the burial] were decided via divination and auspicious signs were received. A fragrant chariot with jeweled banners sent [Lou’s remains] to the side of River Yi. [Her body] was placed on the secluded cliff, and [her] soul was stored in desolate rocks. This was called the rule of Śītavana. This is in accordance with the Rites. Crows cawed by the river, [as if] grieving for [the loss of] the sorrowful children. A migrating goose honked alone, adding to the inexpressible despair of a widower.Mourning [in front of the] blue limestone, [Shen Li] reverently dedicated a shrine of King Udayana’s [image of Śākyamuni]. The ūrṇā in between the eyebrows was more dazzling than the sun. The jeweled necklace beneath the face outshines all stars. The dignity of the image would last for eternity, and the radiance would always be complete. [Shen Li transferred the merit] first to the emperor. May his sagely influence [filled] the heaven and the earth. Then [Shen Li transferred the merit] to all sentient beings in the Dharma realm… as long-lasting as the sun and the moon…[All] attain true enlightenment.2大唐龍朔元年十一月廿三日洛陽縣文林郎沈裏(裒)為亡妻婁氏敬造優填王像一龕,以言記事,勒之于后。觀夫至道無(善)道,知此(妙)道之難測;至言無言,寔微言之秘旨。言以道著,道自言生。道因言以賦名,言據道而彰德。故知是法非法,舍利演無窮之端;小形大形,觀音現神通之力。然婁宿殖德本,早瑩禪心,識幻真幻之機,表身非身之始。重一法于山嶽,輕千金若鴻毛。鄙時俗之送(逸)終,精(枕)寳(衣)綉于泉壤。慕先哲之歸向,寂分軀于草莽。顯慶五年十二月寢疾於思恭之第而譫裏3曰:“笄冠之初,契期偕老。豈意非福,痼瘵纏躬。不諱之後,願從所志。”其月廿八日薨於私(内)第(室)。遂延僧請佛,度(庭)建法壇。設供陳香,累七不絕。筮箴(辰)卜日,休兆葉從。寳幢(幡)香車,送歸伊濱(嶺)。尸陳戢唐(崖),魂藏孤岩,寔曰屍陀法,禮也。寒鴉岸叫,痛悲稚之斷腸;旅雁孤鳴,助鰥夫之鬱鯁。悼□青岩,敬造優填王一龕。其像思(眉)間毫相,共慧日而爭輝(暉);頤下珠瓔,與衆星之競耀。威嚴自(永)在,光相具足。上爲 皇帝陛下,聖化與天地同界;下為法界蒼生,□□共日月等歲,□□□□,俱登正覺。

…disposing the dead in a grove slightly reduces the petty and stringent heart. Animals feed on it and beings from the dark realm thrive from its vapor. What can be gained [by those who offered their bodies] rarely makes up for what is lost. When insects and maggots gush out of the flesh, birds follow to peck and swallow in disorder. To leave flesh on the open field is to aggrieve the compassionate.4…陳屍林薄。少袪鄙悋之心。飛走以之充飢。幽明以於熏勃。得夫(失)相補尠能兼濟。遂有蟲蛆涌於肉外。烏隨啄呑狼籍。膏於原野傷於慈惻。(Daoxuan, Xu gaosengzhuan, T vol. 50, no. 2060, 0685a27–0685b01)

Transmitted to East Xia (China) were only [the burials in] groves and in the earth. Burials in rivers and by cremation were hardly found. In the past, pottery was used as the coffins of the people of Yu (Youyu 有虞, descendants of the legendary Emperor Shun舜). [Such] was the beginning of abandoning [the practice of covering the dead] with wood and [leaving it] in a grove. [The people of] Xiahou used baked bricks to line [the walls around the coffin], [continuing] the use of pottery coffins. The people of Yin (Shang dynasty, c. 1600–1045 BCE) used wood to make coffins and bound them with rattan.In the Middle Antiquity, the study of texts flourished and [the sages] cultivated [people] with ren, leading to an orderly governing. [The sage rulers] understood that few entombed the dead, and thus covered the decayed remains and buried them. In the Upper Antiquity, [people] entombed [the dead] but did not erect any signs for the tomb. [This practice was] not circulated among all beings. After Hexu and [Zun]lu [from the Upper Antiquity used] burial mounds, now [people] established burial mounds on hills. In the Lower Antiquity, burial in the earth was continued, in various forms that were difficult to record.東夏所傳惟聞林土。水火兩設世罕其蹤。故瓦掩虞棺。廢林薪之始也。夏后聖(堲)周。行瓦棺之事也。殷人以木槥櫝。藤緘之也。中古文昌仁育成治。雖明窆葬行者猶希。故掩骼埋胔堋而瘞也。上古墓而不墳。未通庶類。赫胥盧陵之后。現即因山爲陵。下古相沿同行土葬。紜紜難紀。(Daoxuan, Xu gaosengzhuan, T vol. 50, no. 2060, 0685b04–0685b11)

[As for] the burials in ancient times, [the deceased] were thickly enshrouded with firewood, and buried amidst wildness. There was no feng nor shu…… the sages from later periods replaced it with inner and outer coffins.古之葬者,厚衣之以薪,葬之中野,不封不樹…… 後世聖人,易之以棺椁。

“There was no feng” means not piling up the earth to make a tomb. “There was no shu” means not planting trees to mark its location.不積土為墳是不封也,不種樹以標其處是不樹也。

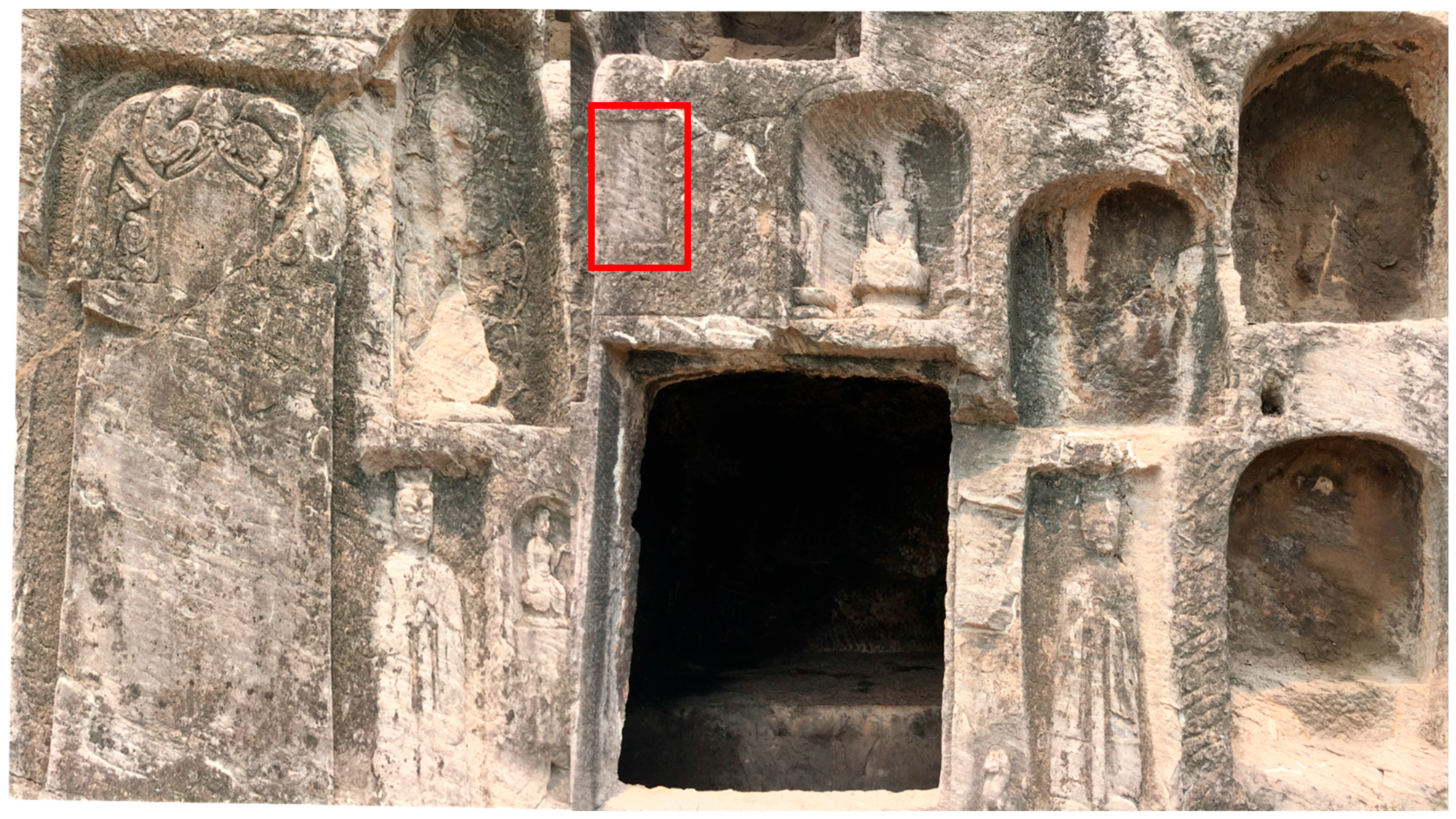

3. Burial Cave of Lady Zhang: Family Ties after Death

Lady Zhang, wife to the late Xiao Yuanli (c. 647–c. 697) who received the posthumous titles of Commissioner with Extraordinary Powers and the Prefect of Xiangzhou. [She] returned to Buddhist (teaching) since young. Engaged with tathatā frequently, she knew that various Dharmas are conditioned… [Her body] was carried in this efficacious shrine. It is hoped that [her] afterlife visage would remain for eternity. An inscription was composed:Immense is the Ultimate Venerable (Śākyamuni) who established the teaching without recompense. Now that [Zhang knew about] the emptiness of form, how could [she] hold on to this body? …故贈使持節相州刺史蕭元禮夫人張氏,少歸佛□,頻涉真如,知諸法之有為,不□有□□□晤金□□□□無□□無禮之源。似存□□,為□若喪,自因□□,載此靈龕,庶使幽容,長垂不朽。乃為銘曰:大哉至尊,立教無報,既空彼相,焉有此身,扙□□累,長為其□。

4. The Problem of Social Gender

5. Posthumous Family Connections for Lay Women

[since the] father died when he was young, the mother remained a widow while raising a son and a daughter. After the daughter was married, the mother passed away. It had been over ten years since then. On the day of the Cold Food Festival, the younger sister returned home. It was the custom of Luoyang that on the day, [descendants] should offer alcohol and food to the tombs [of ancestors]. Riding the donkey, the son went. The tomb [of their parents] were to the east of the River Yi. As [the son] was about to across the river, the donkey refused to proceed. [The son] whipped its head to bleed. Having arrived at the tomb, [he] let loose of the donkey in order to present the offerings. Soon the donkey disappeared and returned to its original location [later].On the same day, the younger sister was at the brother’s home alone. Suddenly [she] saw her mother entered. Bleeding in the head and mutilated in face, [the mother] wailed and told the daughter, ‘When I was alive, I sent you five sheng of rice behind your brother’s back. For this act, I was punished with sinful karma and reborn in the body of a donkey. [As a donkey] I have repaid your elder brother for five years. Today [he] wanted to cross the River Yi. Since the water is so deep, [I] was afraid of [crossing]. Your elder brother beat me with his whip, wounding my head and face. If [I] returned home, [I am] afraid that he would beat me again. [Thus] I ran to tell you: now I have paid back all my debts, why [would we still] inflict so much unreasonable suffering on each other?’ Having finished her words, [the donkey] walked out and cannot be found again. [But] the daughter took note of her wounds.Soon the brother came back. The daughter went to observe the bleeding wounds on the donkey and realized that they were the same as her mother’s. Holding the donkey in arms, she cried. The brother was surprised, asking her about the matter. The daughter told him about the situation. The brother confirmed that earlier, [the donkey] refused to cross the river, and that it returned after disappearing; the circumstance was the same [as what the daughter described]. Then the siblings held one another and cried with grief. Although the donkey also wept, it still refused to drink water or eat grass. The siblings kneeled to plead, ‘If you are indeed our mother, please eat the grass”. The donkey immediately ate some but stopped shortly again. Not knowing what to do, the siblings prepared millet and beans, and send [them with the donkey] to the place of Wujie (Mr. Wang). Only after that did [the donkey] eat and drink again. Later, when the donkey died, the sister collected [its remains] and buried it.早喪父,其母寡,養一男一女;女嫁而母亡。亦十許年矣。寒食日,妹來歸家,家有驢數年。洛下俗,以寒食日,持酒食祭墓。此人乘驢而往,墓在伊水東,欲度伊水,驢不肯度,鞭其頭面,被傷流血。既至墓所,放驢而祭。俄失其驢。還在本處。是日,妹獨在兄家,忽見母入來,頭面血流,形容毀瘁,號泣告女曰:“我生時,避汝兄送米五升與汝,坐此得罪報,受驢身。償汝兄五年矣。今日欲度伊水,水深畏之,汝兄以鞭捶我,頭面盡破,仍許還家,更苦打我。我走來告汝,吾今償債垂畢,何太非理相苦也。”言訖,走出,尋之不見。女記其傷狀處。既而兄還,女先觀驢頭面傷破流血,如見其母傷狀,女抱以號泣。兄怪問之,女以狀告,兄亦言初不肯度,及既失還得之狀同。於是兄妹抱持慟哭,驢亦涕淚交流,不食水草。兄妹跪請:“若是母者,願為食草。”驢即為食草,既而復止。兄妹莫如之何,遂備粟豆,送五戒處。乃復飲食。後驢死,妹收葬焉。

In the eastern capital (Luoyang) of the Tang dynasty, in Daode Ward, there was a scholar. One evening, when walking to the Middle Bridge, he stumbled upon an aristocratic entourage, accompanied by luxurious carts and horses. Seeing the scholar, [the aristocrats] talked to him and asked him to follow the entourage. [Inside the team] there was a princess, about twenty years old, whose beauty was unparalleled in the world. [As she] continued to converse with the scholar, the group left the Changxia Gate in the south [of the city], arriving at Longmen where they entered a splendid mansion filled with orchid fragrance. [The princess] summoned the scholar, bestowed him fine cuisines, and slept with him. In midnight, the scholar was awakened and saw where he was sleeping was a stone cave. In the front was a dead woman whose corpse had become swollen. In moonlight, it was unbearable to smell the stink of the corpse. The scholar then climbed on the stone, barely finding his way out. At dawn [he] arrived at Xiangshan Monastery and told what happened to the monk there. The monk sent him back home. Several days later, he died. [The story is] from Jiwen.[唐東]都道德里有一書生。日晚行至中橋。遇貴人部從。車馬甚盛。見書生。呼與語。令從後。有貴主。年二十餘。丰姿絕世。與書生語不輟。因而南去長夏門。遂至龍門。入一甲第。華堂蘭室。召書生賜珍饌。因與寢。夜過半。書生覺。見所臥處。乃石窟。前有一死婦人。身王洪漲。月光照之。穢不可聞。書生乃履危攀石。僅能出焉。曉至香山寺。為僧說之。僧送還家。數日而死。出紀聞。

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The five burial caves with inscriptions include the ones of Ladies Lou and Zhang, which are the focus of this paper, and the ones of nun Lingjue 靈覺 (c. 687–738) and nun Huideng 惠燈 (650–731), which are briefly introduced in the later part of this paper. The fifth one is known as Wanfogou Cave 1, published in 2021. The fragmented inscription does not include the name of the cave occupant but mentions the second son of a certain Zhang Sijing 張思敬 (Longmen shiku yanjiu yuan 2021, vol. 1, pp. 24–25). I also learned about this burial cave from Lan Li (2022), who participated in the excavation of Wanfogou in 2015. |

| 2 | Unless otherwise noted, all translations in this paper are by the author. |

| 3 | The character is neither transcribed in the 1998 version nor legible from the ink rubbing. Thus, it is uncertain if the husband’s name was Shen Li or Shen Pou. |

| 4 | I translate this passage differently from Shufen Liu (2000, p. 8). Liu interprets these words as conveying Daoxuan’s “admiration of the ideals” and “sense of revulsion at its actual undertaking”. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | This translation is from Legge (1885, p. 176). For names, the old transliterations are adapted with pinyin romanization. |

| 7 | Taiping guangji was not reprinted until the sixteenth century (Ditter et al. 2017, p. 19). |

References

- Adamek, Wendi L. 2016. Meeting the Inhabitants of the Necropolis at Baoshan. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 29: 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill, Stephanie. 2016. The Sutra on Transforming the Female Form: Unpacking an Early Medieval Chinese Buddhist Text. Journal of Chinese Religions 44: 127–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkwill, Stephanie. 2018. Why Does a Woman Need to Become a Man in Order to Become a Buddha: Past Investigations, New Leads. Religion Compass 12: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campany, Robert Ford. 2018. Miracle tales as scripture reception: A case study involving the Lotus Sutra in China, 370–750 CE. Early Medieval China 2018, no. 24: 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2014. Meditation Traditions in Fifth-Century Northern China: With a Special Note on a Forgotten ‘Kaśmīri’ Meditation Tradition Brought to China by Buddhabhadra (359–429). In Buddhism across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cultural Exchange. Edited by Tansen Sen. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, vol. 1, pp. 101–29. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Jessey. 2022. Inscribing Death: Burials, Representations, and Remembrance in Tang China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667). 645. Xu Gaosengzhuan 續高僧傳. T vol. 50, no. 2060. From Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō大正新脩大藏經. Available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/satdb2015.php (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Ditter, Alexei Kamran, Jessey Choo, and Sarah M. Allen, eds. 2017. Tales from Tang Dynasty China: Selections from the Taiping Guangji. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Baiyi 關百益 (1882–1956). 1980. Yique shike tubiao 伊闕石刻圖表. Beijing: Zhongguo Shudian. First published in 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielminotti Trivel, Marco. 2006. Archaeological Evidence from the ‘Buddhist Period’ in the Longmen Area. Annali dell’ Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” 66: 139–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kumārajīva (344–413). Pusa Hese Yufa Jing 菩薩訶色欲法經. T vol. 15, no. 615. From Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō. Available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/satdb2015.php (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Lai, Ziyang. 2021. Sui Tang Luoyang cheng lifang men de xingzhi. Dazhong kaogu, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sonya S. 2019. A Landscape Fit for the Great Buddhas: On Cliff Tombs and Buddhist Cave-Temples in Leshan. In Refiguring East Asian Religious Art: Buddhist Devotion and Funerary Practice. Edited by Wu Hung and Paul Copp. Chicago: Art Media Resources, Inc., pp. 237–60. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, James, trans. 1885. The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Confucianism, Part III the Li Ki, I-X. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang 李昉 (925–996), ed. 1566. Taiping Guangji 太平廣記. Microfilm No. 08507 from Beiping Tushu Guan, Now in Guojia Tushu Guan, Taipei; First published in 978. Available online: https://rbook.ncl.edu.tw/NCLSearch/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Li, Lan. 2022. “The solitary cliff that hides the soul”: Cave burial as funerary practice at Longmen in the Tang dynasty. Paper presented at American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 20 November. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wensheng. 1994. Longmen shiku fojiao yizang xingzhi de xin faxian. Yishuxue 11: 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wensheng, and Chaojie Yang. 1995. Longmen shiku fojiao yizang xingzhi de xinfaxian. Wenwu, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiaoxia. 2019. Longmen shiku wanfogou xin faxian. Kaogu Yanjiu 163: 158–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lingley, Kate A. 2006. The Multivalent Donor: Zhang Yuanfei at Shuiyu Si. Archives of Asian Art 56: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingley, Kate A. 2019. A Hybrid Inscription at Shuiyusi: The Buddhist Funerary Record. Fojiao Shi Yanjiu 3: 111–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jinglong, and Yukun Li, eds. 1998. Longmen Shiku Beike Tiji Huilu. Beijing: Zhongguo Da Baike Quanshu Chubanshe, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen. 2000. Death and the degeneration of life exposure of the corpse in medieval Chinese Buddhism. Journal of Chinese Religions 28: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen. 2008. Zhonggu de Fojiao Yu Shehui. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wei. 2012. Longmen Tang Xiao Yuanli qi Zhang shi yiku kaocha zhaji. Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan Guankan, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Longmen shiku yanjiu yuan, Beijing daxue kaogu wenbo xueyuan, and Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan shijie zongjiao yanjiu suo, eds. 2018. Longmen Shiku Kaogu Baogao: Dongshan Leigutai Qu. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, Zhengzhou: Longmen Shuju, 6 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Longmen shiku yanjiu yuan, ed. 2021. Longmen Shiku Kaogu Baogao: Dongshan Wanfogou Qu. Beijing: Kexue Chuban She, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Chaolin 路朝霖 (fl. 1876), ed. 2006. Luoyang Longmen Zhi 洛陽龍門志. Yangzhou: Guangling Shushe. First published in 1887 and 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Jinsong, and Chaojie Yang. 1999. Longmen shiku xin faxian de liangzuo Tangdai yiku. In Gengyun Luncun (Yi). Edited by Luoyang Shi and Wenwu Ju. Beijing: Kexue Chuban She, pp. 100–13. [Google Scholar]

- Luoyang Shi Longmen Wenwu Baoguansuo. 1986. Luoyang Longmen Xiangshansi yizhi de diaocha yu shijue. Kaogu, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Yangguang. 2016. Luoyang chutu Tang shujia Xiao Liang muzhi ji xiangguan wenti yanjiu. Zhongyuan Wenwu, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert, Carmen. 2022. Beyond Spatial and Temporal Contingencies: Tantric Rituals in Eastern Central Asia under Tangut Rule, 11th–13th C. In Buddhism in Central Asia II: Practice and Rituals, Visual and Material Transfer. Edited by Yukiyo Kasai and Henrik H. Sørensen. Brill: Leiden, pp. 313–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Run’an. 2006. Dunhuang Sui Tang yiku xingzhi de yanbian ji xiangguan wenti. Dunhuang Yanjiu 99, no. 5: 56–62, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Poo, Mu-Chou. 1990. Ideas concerning Death and Burial in Pre-Han and Han China. Asia Major 3, no. 2: 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Yuan 阮元 (1764–1849), ed. 1815a. Zhouyi jianyi 周易兼義, with annotation Zhouyi zhengyi 周易正義by Kong Yingda 孔穎達 (574–648). In Chongkan Songben Shisanjing Zhushu Fu Jiaokan Ji 重刊宋本十三經注疏附校勘記. From Hanji Dianzi Wenxian Ziliaoku 漢籍電子文獻資料庫. Available online: https://hanchi.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/ihp/hanji.htm (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Ruan, Yuan, ed. 1815b. Fu shiyin Liji zhushu 附釋音禮記注疏, annotated by Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200) and Kong Yingda. In Chongkan Songben Shisanjing Zhushu Fu Jiaokan Ji. From Hanji Dianzi Wenxian Ziliaoku. Available online: https://hanchi.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/ihp/hanji.htm (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Sharf, Robert H. 2013. Art in the Dark: The Ritual Context of Buddhist Caves in Western China. In Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and Its Conservation: Proceedings of the Buddhist Art Forum 2012. Edited by David Park, Kuenga Wangmo and Sharon Cather. London: Archetype Publications, pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Lingling. 2015. Tianlongshan fojiao yizang xingshi zongshu. Wenwu Shijie, 7–9, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Xingyan 孫星衍 (1753–1818), and Shu Xing 邢樹 (fl. 1759–1823). 1891. Huanyu fangbei lu寰宇訪碑錄. In Xin Jiao Pingjin Guan Congshu 新斠平津館叢書. Wuxian: Zhushi Huailu Jiashu, 12 vols. First published in 1802. From University of Michigan. HathiTrust. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015045700815 (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Tang, Lin 唐臨 (600–659). n.d. Mingbao Ji 冥報記. T 2082, vol. 51. From Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō. Available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/satdb2015.php (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Wang, Nan. 2018. Tangdai shujia Lanling Xiao shi jiazu beizhi jizheng: Yi Xiao Cheng kunzhong wei zhongxin. Gugong Bowu Yuan Yuankan, 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qufei. 1955. Guanyu Longmen shiku de jizhong xin faxian jiqi youguan wenti. Wenwu Cankao Ziliao, 120–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Yucheng. 1986. Longmen Fengxiansi yizhi diaocha ji. Kaogu Yu Wenwu, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Yucheng. 1993. Longmen suojian liang Tangshu zhong renwu zaoxiang gaishuo. Zhongyuan Wenwu, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Shifen 吳式芬 (1796–1856). 1852–1874. Jungu Lu 攟古錄. vols. 7–9 of 20 vols. Haifeng: Wu Family Print, From Library of the University of California. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.c088034125 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Xu, Song 徐松 (1781–1848). 1985. Tang Liangjing Chengfang Kao 唐兩京城坊考. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. First published in 1809. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Duo 楊鐸 (1813–1879). 1867. Zhongzhou Jinshi Mulu 中州金石目錄. vols. 3–4 of 8 vols. Reproduced in Congshu Jicheng Xubian 叢書集成續編. 1994, vol. 75. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, 383–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yi. 2019. Death Ritual in the Tang Dynasty (618–907): A Study of Cultural Standardization and Variation in Medieval China. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Ping. 2002. Until Death Do Us Unite: After life Marriages in Tang China, 618–906. Journal of Family History 27: 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Yan 姚晏 (fl. 1810). 1883. Zhongzhou jinshi mu 中州金石目. vols 3 and supplement of 4 vols. In Zhijin Zhai Congshu 咫進齋叢書. Edited by Jinyuan Yao 姚覲元 (fl. 1843). Shunde: Publisher Not Identified, vol. 2, From Cornell University Library. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924025586565 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Zhang, Naizhu, and Chengyu Zhang. 1999. Luoyang Longmen shan chutu de Tang Li Duozuo muzhi. Kaogu, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Naizhu. 1991. Longmen shiku Tangdai yiku de xinfaxian jiqi wenhua yiyi de tantao. Kaogu, 160–69, pl. 8, Reproduced in Zhang, Naizhu. 1993. Longmen shiku Tangdai yiku de xin faxian jiqi wenhua yiyi de tantao. In Longmen Shiku Yanjiu Lunwen Xuan. Edited by Longmen Shiku Yanjiu Suo. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Meishu Chubanshe, pp. 241–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Naizhu. 2010. Xin chu Tang zhi yu zhonggu Longmen jingtu chongbai de wenhua shengtai: Yi Xiao Yuanli muzhi jishi wei yuanqi. Tang Yan Jiu 16: 507–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Naizhu. 2011. Longmen Quxi Shike Wencui. Beijing: Beijing Tushu Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junping, and Wencheng Zhao, eds. 2007. Heluo Muke Shiling. Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chuban She, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Lisheng, and Yucheng Wen. 1986. Yitong yu Tang shi, zhongya shi youguan de xin chutu muzhi. Xibei Shidi 3: 19–21, Reprint in Zhao, Lisheng. 2002. Zhao Lisheng Wenji. vol. 2. Lanzhou: Lanzhou Daxue Chuban She, pp. 400–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Zhiqian 趙之謙 (1829–1884). 1864. Bu Huanyu Fangbei Lu 補寰宇訪碑錄. 4 vols. From Columbia University Libraries. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc1.cu51461676 (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Zheng, Yi. 2020. Zhonggu gaoseng yimai kongjian de wuzhi xing. Zhongguo Meishu 59, no. 2: 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shaoliang, and Chao Zhao, eds. 1992. Tangdai Muzhi Huibian. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chuban She, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, P. Posthumous Release for Lay Women in Tang China: Two Cases from the Longmen Grottoes. Religions 2023, 14, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030365

Zhu P. Posthumous Release for Lay Women in Tang China: Two Cases from the Longmen Grottoes. Religions. 2023; 14(3):365. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030365

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Pinyan. 2023. "Posthumous Release for Lay Women in Tang China: Two Cases from the Longmen Grottoes" Religions 14, no. 3: 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030365

APA StyleZhu, P. (2023). Posthumous Release for Lay Women in Tang China: Two Cases from the Longmen Grottoes. Religions, 14(3), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030365