Minding the Gaps in Managers’ Self-Realisation: The Values-Based Leadership Discourse of a Diaconal Organisation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Perspectives

2.1. Self-Realisation as Individualisation and Individuation

2.2. Values and Leadership in Diaconal Organisations

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Discourse as an Integrating Force in the Organisation

Respect: Understanding and respecting the complex needs of vulnerable patients and their kin as well their personal integrity and characteristics.

Quality: The hospital’s services should be of high quality, ensuring commitment to professional competency and best practices.

Service/serving: Every interaction with patients, kin and employees is an opportunity to offer services, be available and express compassion and care.

Justice: The hospital will safeguard patients’ and their kin’s rights, represent vulnerable groups and strive for the right and effective use of resources.

Engaged for humans and in the belief that each human being has value as created in the eyes of God, creating a mutual community with God and fellow human beings by caring for human beings in distress. Renewers in service for our neighbours.

I left a commercial health enterprise to work here. I did not want to make the rich even wealthier; rather, I would make I difference here for those in need. I feel I develop as a person. Basically, we are here to serve—there is no contradiction.

All managers are expected to promote and cherish the core values. We seek to continue in the spirit of the founders from back in the 1800s. Doing something that is not mainstream, dare to challenge and, above all, serve the common good.

We exist to improve the quality of patient treatment and care. Our managerial circle—planning, doing, controlling and improving—centres around the core values. Thus, we focus on strategic questions that lead us forward. The alternative would be managers going about their daily business without development or improvement.

4.2. The Discourse as a Resource in Dilemmas and Prioritising

Good managers guide their employees along to grasp and see the whole picture. They identify with the patients and at the same time see the totality. This is extraordinarily demanding. Clear leaders know and show the direction and can articulate to their co-workers what they expect.

How do managers show respect? The CEO has a blog. He got a mail from an employee who had heard a speech by the CEO to which he gave positive feedback. However, he also commented that every second sentence did not need to end with “you see…?” The CEO found this a valuable contribution and asked the employee to publish this remark on the blog. Thus, he showed that it is ok to give and take criticism.

The core values create dilemmas in everyday managerial life. This creates reflections in the clinic all the time. What does it mean to behave respectfully? How do we show justice in a situation when we are crowded with patients and do not have room for more? I believe managers discuss these matters continuously. And what is sufficient quality when we must take the finances into account? Values are expressed and put upfront in dilemmas.

The hospital naturally wants the most out of the money, delivering top-quality services with less money. Make patients healthy and happy. Yes, practise in line with the core values without superseding the budget. There we always have to fight; we are not at ease with that balance. Justice is to distribute according to needs.

The values are nice, yet when everyday life is messy, they seem a bit hypocritical. Nonetheless, values help us lift our gaze and hope for a better tomorrow. Even when I am angry with the top management, I need to motivate my employees in the ward.

4.3. The Discourse Creates a Sense of Coherence

The values are generic. I am not a Christian and do not relate to the element of faith; however, I have no problems relating to the value element. I can burn as much for those as those with a religious point of view.

This is a value that makes us special. It has a lot of different interpretations here. It can be associated with compassion and neighbourly love—in short, the diaconal tradition and Christian anchoring of this institution. We do not talk that much about it. It lies at the bottom as a fundamental to which we have related.

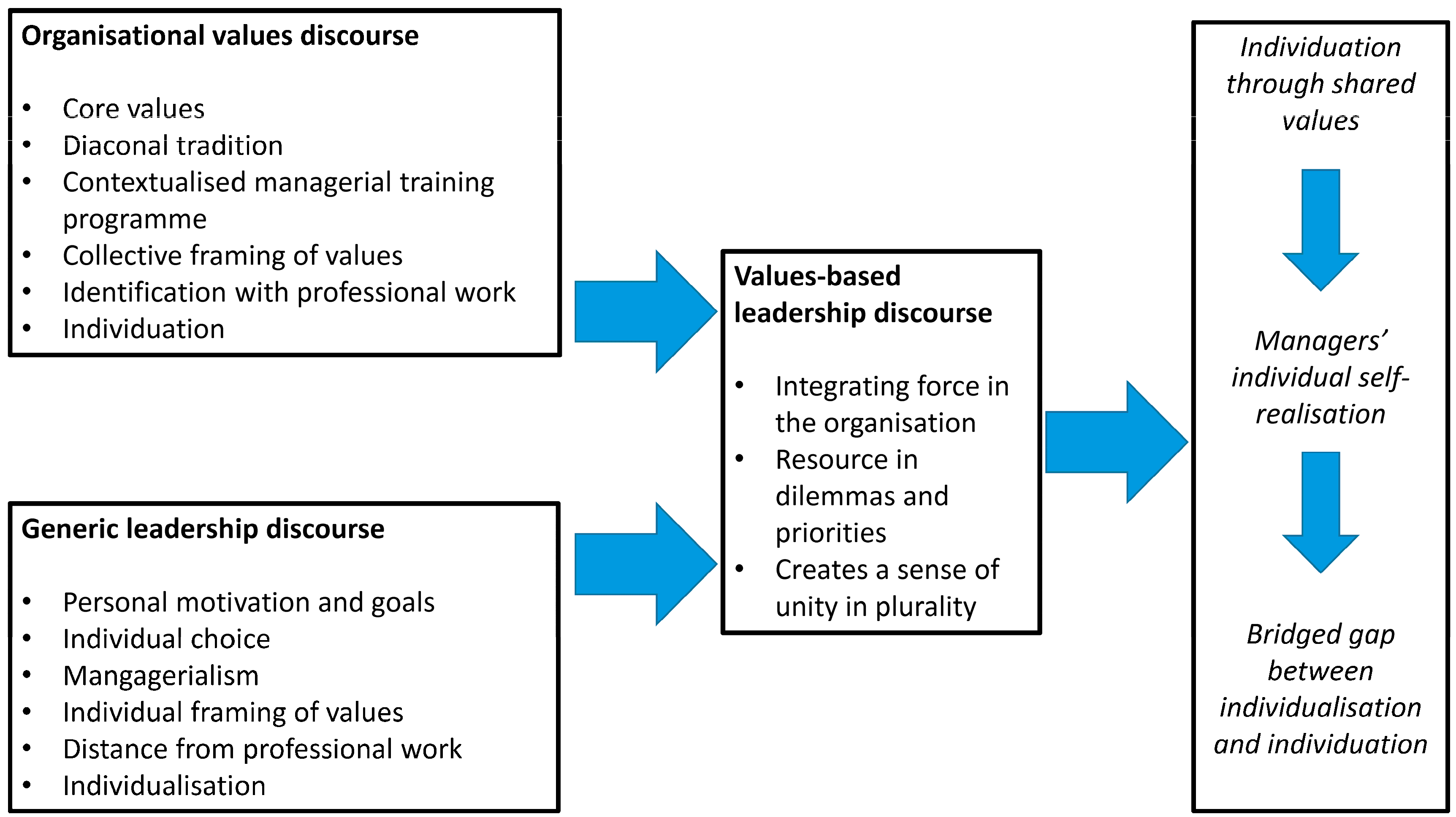

5. Discussion

5.1. Individuation through Shared Values

5.2. Managers’ Self-Realisation as Individualisation

5.3. The Gap between Individualisation and Individuation

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | https://www.eurodiaconia.org/who-we-are/presentation/ (accessed on 3 April 2023). |

References

- Aadland, Einar, and Harald Askeland. 2017. Verdibevisst Ledelse. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Aadland, Einar, and Morten Skjørshammer. 2012. From God to good? Faith-based institutions in the secular society. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion 9: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, Stuart, and David A. Whetten. 1985. Organizational identity. In Research in Organizational Behavior. Edited by Larry L. Cummings and Barry M. Staw. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 263–95. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, Mats, and Andre Spicer. 2010. Metaphors We Lead by: Understanding Leadership in the Real World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, Mats, and Dan Karreman. 2000. Varieties of discourse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis. Human Relations 53: 1125–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Chris, and Donald Schon. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Approach. Reading: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Askeland, Harald. 2015. Managerial practice in faith-based welfare organizations. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 28: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askeland, Harald, Gry Espedal, and Stephen Sirris. 2019. Values as vessels of religion? Role of values in everyday work at faith-based organisations. Diaconia Journal of the Study of Christian Social Practice 1: 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and William L. Gardner. 2005. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2007. Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Billis, David. 2010. Hybrid Organizations and the Third Sector: Challenges for Practice, Theory and Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, Don S. 1995. A Fundamental Practical Theology: Descriptive and Strategic Proposals. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, Jan W. 2013. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. London and Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Adalbert. 2013. Hybridisation in German public services—A contested field of innovations. In Civil Societies Compared: Germany and The Netherlands. Edited by Annette Zimmer. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirth, Alan. 1998. Self-Fulfillment. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Standford: Standford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Hans Morten. 2018. Diakoni i velferdssamfunnet. Mangfold og dilemmaer. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, Lars Skov, Kristin Strømsnes, and Lars Svedberg. 2018. Civic Engagement in Scandinavia. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, Axel. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition. The Moral Grammer of Social Conflicts. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, Axel. 2004. Organized self-realization: Some paradoxes of individualization. European Journal of Social Theory 7: 463–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, Stan. 2008. Beyond homo economicus: Recognition, self-realization and social work. British Journal of Social Work 40: 841–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Urs P., and Andreas Schröer. 2014. Integrated organizational identity: A definition of hybrid organizations and a research agenda. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25: 1281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeavons, Thomas H. 1992. When the management is the message: Relating values in management practice in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2: 403–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, Kevin P. 2003. The effects of government funding on management practices in faith-based organizations: Propositions for future research. Public Administration and Management: An Interactive Journal 8: 116–34. [Google Scholar]

- Klaasen, John Stephanus. 2020. Diakonia and diaconal church. Missionalia: Southern African Journal of Mission Studies 48: 120–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laceulle, Hanne, and Jan Baars. 2014. Self-realization and cultural narratives about later life. Journal of Aging Studies 31: 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis-Peters, Annette. 2014. Diaconal work and research about Diakonia in the face of welfare mix and religious pluralism in Sweden and Germany. In Diakonia as Christian Social Practice: An Introduction. Edited by Stephanie Dietrich, Knud Jørgensen, Kari Karsrud Korslien and Kjell Nordstokke. Oxford: Regnum Books, pp. 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Løvaas, Beate Jelstad, Stephen Sirris, and Asbjørn Kaasa. 2019. Har ledelse av frivillige noe å tilføre ledere i kunnskapsorganisasjoner? Beta 33: 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, Alisdair. 1984. After Virtue. A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Florentine, Michael Meyer, and Martin Steinbereithner. 2016. Nonprofit organizations becoming business-like: A systematic review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45: 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, Dan P., and Kate C. McLean. 2013. Narrative identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science 22: 233–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstokke, Kjell. 2011. Liberating Diakonia. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstokke, Kjell. 2014. The study of diakonia as an academic discipline. In Diakonia as Christian Social Practice: An introduction. Edited by Stephanie Dietrich, Knud Jørgensen, Kari Karsrud Korslien and Kjell Nordstokke. Oxford: Regnum Books International, pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Offe, Claus. 2018. Contradictions of the Welfare State. London: Routledge, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Reedy, Patrick, Daniel King, and Christine Coupland. 2016. Organizing for individuation: Alternative organizing, politics and new identities. Organization Studies 37: 1553–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, Ronald E., and Sarah Smith Orr. 2004. Improving Leaderhip in Nonprofit Organizations. Haboken: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Hillel. 2013. Nonprofit human services: Between identity blurring and adaptation to changing environments. Administration in Social Work 37: 242–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana, and Matthias Hoof. 2012. Meaningful commitment: Finding meaning in volunteer work. Journal of Beliefs and Values 33: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, Richard. 1998. The Corrosion of Character: The Transformation of Work in Modern Capitalism. New York: Norton Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sider, Ronald James, and Heidi Rolland Unruh. 2004. Typology of Religious Characteristics of Social Service and Educational Organizations and Programs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33: 109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirris, Stephen. 2019. Coherent identities and roles? Hybrid professional managers’ prioritizing of coexisting institutional logics in differing contexts. Scandinavian Journal of Management 35: 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirris, Stephen. 2020a. Institutional complexity challenging values and identities in Scandinavian welfare organisations. In Understanding Values Work. Edited by Harald Askeland, Gry Espedal, Beate Jelstad Løvaas and Stephen Sirris. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sirris, Stephen. 2020b. Values as Fixed and Fluid: Negotiating the Elasticity of Core Values. In Understanding Values Work. Edited by Harald Askeland, Gry Espedal, Beate Jelstad Løvaas and Stephen Sirris. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sirris, Stephen, and Haldor Byrkjeflot. 2019. Realising calling through identity work. Comparing themes of calling in faith-based and religious organisations. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 32: 132–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Bryan J. Dik, and Ryan D. Duffy. 2012. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment 20: 322–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveningsson, Stefan, and Mats Alvesson. 2003. Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Human Relations 56: 1163–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveningsson, Stefan, and Mats Alvesson. 2016. Managerial Lives: Leadership and Identity in an Imperfect World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 1989. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 1991. The Ethics of Authenticity. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Harvard: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tengblad, Stefan. 2012. The Work of Managers: Towards a Practice Theory of Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, Fred O., Bruce J. Avolio, William L. Gardner, Tara S. Wernsing, and Suzanne J. Peterson. 2008. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management 34: 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, Clark McCauley, Paul Rozin, and Barry Schwartz. 1997. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality 31: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hospital Unit/Factors | Medical | Psychiatric | Surgery | Top-Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observee | Unit manager | Ward manager | Unit manager | CEO |

| Professional background | Nurse | Psychiatrist | Nurse | Economist |

| Duration (days) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Field notes (pages) | 27 | 24 | 30 | 5 |

| Individual interviews | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 (CEO, HR director, communication director, director of finance, secretary, advisor) |

| Average duration (minutes) | 53 | 61 | 47 | 39 |

| Transcription (pages) | 36 | 47 | 33 | 54 |

| Group interviews (participants) | 2 (9) | 3 (14) | 2 (8) | 0 |

| Participants’ average age and tenure | 32 (4) | 54 (13) | 46 (9) | 55 (6) |

| Average duration (minutes) | 69 | 58 | 48 | 0 |

| Transcription (pages) | 28 | 37 | 24 | 0 |

| Document (pages) | 36 | 80 | 42 | 245 |

| Exemplary Quote | Code | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| The hospital’s core values—quality, justice, service and respect—are our values. | Core values | Values ubiquity | Values-based leadership discourse as an integrating force in the organisation |

| All employees and managers are expected to promote and cherish the values. | Promoting values | Values manifestations | |

| Our managerial circle—planning, doing, control and improving—surround the core values; we foster values-based improvement leadership. | Managerial training programme | Values-based leadership | |

| What we do with our values in practice can distinguish managers from others. | Values in practices | Focus and priorities | Values-based leadership discourse as a resource in dilemmas and priorities |

| Serving is a value that makes managers special. It has a lot of different interpretations surfacing in discussions. | Choosing a course of action | Individuation | |

| Managers experience many simultaneous conflicts between values, including with their individual ones. | Tensions between values | Individualisation | |

| A diaconal hospital enjoys a tradition that managers must interpret. | Present and past | Identification | Values-based leadership discourse creates a sense of unity |

| Managers’ mundane everyday activities are considered expressions of values. | Work activities | Linking actions with values | |

| Leading is to motivate people to perform the tasks that are part of the mission. | Tasks and mission | Leadership | |

| Values concern the totality of our organisation—how patients are met and managers’ awareness of the values. | Levels and departments | Coherence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sirris, S. Minding the Gaps in Managers’ Self-Realisation: The Values-Based Leadership Discourse of a Diaconal Organisation. Religions 2023, 14, 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060722

Sirris S. Minding the Gaps in Managers’ Self-Realisation: The Values-Based Leadership Discourse of a Diaconal Organisation. Religions. 2023; 14(6):722. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060722

Chicago/Turabian StyleSirris, Stephen. 2023. "Minding the Gaps in Managers’ Self-Realisation: The Values-Based Leadership Discourse of a Diaconal Organisation" Religions 14, no. 6: 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060722

APA StyleSirris, S. (2023). Minding the Gaps in Managers’ Self-Realisation: The Values-Based Leadership Discourse of a Diaconal Organisation. Religions, 14(6), 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060722