Abstract

Social media, especially Twitter, has become a platform where hate, toxic, intolerant, and discriminatory speech is increasingly spread. These messages are aimed at different vulnerable social groups, due to some of their differentiating characteristics with respect to the dominant one, whether they are phenotypic, religious, cultural, gender, sexual, etc. Of all these minorities, one of the most affected is the Muslim community, especially since the beginning of the Mediterranean refugee crisis, during which migration from the Middle East and North Africa increased considerably. Spain does not escape this reality as, given its proximity to Morocco, it is one of the main destinations for migrants from North Africa. In this context, there are already several studies focused on specifically investigating Islamophobic speech disseminated on social platforms, normally focused on specific cases. However, there are still no studies focused on analyzing the entire conversation around Islam and the Muslim community that takes place on Twitter and in a southern European country such as Spain, aiming to identify the latent sentiments and the main underlying topics and their characteristics, which would help to relativize and dimension the relevance of Islamophobic messages, as well as to analyze them from a more solid base. The main objective of the present study is to identify the most frequent words, the main underlying topics, and the latent sentiments that predominate in the general conversation about Islam and the Muslim community on Twitter in Spain and in Spanish during the last 8 years. To do this, 190,320 messages that included keywords related to Muslim culture and religion were collected and analyzed using computational techniques. The findings show that the most frequent words in these messages were mostly descriptive and not derogatory, and the predominant latent topics were mostly neutral and informative, although two of them could be considered reliable indicators of Islamophobic rejection. Similarly, while the overall average sentiment in this conversation trended negatively, neutral and positive messages were more prevalent. However, in the negative messages, the sentiment was considerably more pronounced.

1. Introduction

In recent years, digital platforms, especially social media, have become a place where toxic and hate speech is hosted and disseminated more than ever before. This speech spreads polarized, intolerant, and discriminatory ideas and attitudes. Ultraconservative and ultra-Catholic groups and political parties have used these platforms to spread their ideology more and more explicitly, taking advantage of the economic, health, environmental, and values crises (Moreno 2020; Tuñón-Navarro and Bouzas-Blanco 2023; Guerrero-Solé et al. 2022). Hate speech is often directed toward minority groups in which different motivating characteristics of discrimination converge, such as national and ethnic origin, phenotypic traits, gender identity, sexual orientation, ideology, social class, or cultural and religious identity. Therefore, different forms of discrimination overlap in hate speech, such as racism, xenophobia, aporophobia, and discrimination on cultural, symbolic, and religious grounds. In Mediterranean countries such as Spain, Islamophobia is on the rise as one of the main forms of discrimination, especially due to the arrival of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers from the Middle East and North Africa, which has increased in recent years due to the crises and conflicts in the region. Although most immigrants in Spain come from Latin America, discrimination and cultural conflicts are more common with immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East, who speak different languages, tend to be from lower social classes, and practice the Muslim religion, which is often stigmatized in Western countries, mostly Catholic. Taking this into account, Islamophobic hate speech has the predominant characteristic of being intersectional, where racist, xenophobic, religious, maurophobic, and/or gender hatreds come together.

In this context, there are numerous studies that provided an approach to the problem in Spain, such as the one developed by Fuentes-Lara and Arcila-Calderón (2023), where Islamophobic hate manifestations were studied on Twitter from hashtags directly related to hatred toward this community, or the study carried out by Zamora-Medina et al. (2021), where the impact of a campaign against Islamophobia on Twitter was quantitatively analyzed. Another example is the work carried out by the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migration through the Spanish Observatory of Racism and Xenophobia (OBERAXE), in which indicators were established to measure hate speech online. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are still no studies focused on analyzing the entire online conversation around Islam or referring to the Muslim population, trying to establish patterns that allow identifying the predominant sentiments, the most frequent words, and the underlying topics and characteristics of the messages related to this community. Thus, through this work, we intend to provide contributions in two main lines. First, we contribute at a theoretical level, in the study and understanding of the discourses about Islam in Spain, through an identification of the sentiments, words, and topics most associated with the Muslim community on Twitter in Spain over a period of 8 years. To do this, we consider not only Islamophobic hate speech, but also the general conversation on this subject and the associated expressions used to refer to the Islamic world. Second, we make a methodological contribution through the use of computational methods, which allowed in this work the search and compilation of all Twitter messages related to Islam and Muslims in the last 8 years, as well as the analysis of sentiments and the extraction of the major underlying topics in a large-scale sample. Specifically, in this paper, we analyze 190,320 messages published on Twitter between 1 January 2015 and 1 January 2023, filtered on the basis of a series of keywords in Spanish related to the Muslim community, and using geolocation search filters to locate the tweets published in the Spanish territory.

The choice of Twitter as a platform for this research is due to its ability to rapidly disseminate information and its open recording of user sentiments and opinions. In addition, it is considered that this platform can provide a more comprehensive view of hate speech and other types of rejection that are freely expressed online, without the barriers that may exist on other social platforms that require user verification or in offline spaces, such as social desirability. It should be noted that, although Twitter does not represent all citizens, its popularity and reach make it a platform of great interest for monitoring and analysis. In fact, authors such as Felt (2016) consider Twitter an ideal tool to directly analyze the attitudes and opinions of society, as well as to detect racism online (Chaudhry 2015; Gualda and Rebollo 2020), due to the easy viralization of content and the speed of communication and transmission of information via all kinds of social agents (Valdez-Apolo et al. 2019). Starting from these postulates, we seek to establish a map of the main sentiments and underlying topics in the conversation related to the Muslim population in Spain within the existing media environment on the social platform, collecting data from Twitter API v.2 and using computational techniques such as natural language processing and topic modeling.

1.1. (Anti)Social Platforms and Twitter

It is common knowledge that the rise of new information and communication technologies, especially digital social media platforms, has brought with it a large number of new social problems and threats. In this way, social media has become the perfect vehicle to disseminate hate ideologies, making use of phenomena such as fake news and taking advantage of the difficulty that it represents for people to distinguish between implausible information and hoaxes. These phenomena have allowed society to find itself immersed in what diverse authors have called the post-truth era or liquid communication (e.g., Del-Fresno-García 2019). The misinformation that is disseminated massively on social platforms often has a clear objective: to polarize society with respect to certain social issues, following political interests, often sowing hatred toward certain groups, such as migrants and refugees, people from other territories, and those with other religious beliefs and practices, which Allport (1954) called outgroups. The pro-human-rights discourse was difficult to refute at the beginning of the 2000s, since, regardless of the majority ideology, there was a tacit social consensus in the defense of human rights. However, at present, especially through social media, prejudiced, intolerant, and discriminatory discourses seem to be able to spread an increasingly hostile, explicit, and violent rejection of all kinds of vulnerable groups, thus attacking the most basic rights of people who are frequently already excluded, marginalized, and stigmatized within a dominant society and culture.

This is what has become known as hate speech, a type of speech spread on social media that is one of the main threats to peaceful coexistence. As the primary and most basic materialization of hate occurs through verbal violence, hate speech constitutes the first step of a ladder that leads to more serious criminal acts against members of certain vulnerable groups, as well as to forms of organized violence, such as terrorism. For this reason, hate speech is being considered as one of the basic hate crimes typified in the penal frameworks of certain European countries, including Spain (article 510 of the penal code), responding to the recommendations made by Europe since the 1990s. The Council of Europe, through its Recommendation No. R(97)20 of the Committee of Ministers on hate speech (Council of Europe 1997), already defined this speech as the promotion of messages that imply rejection, contempt, humiliation, harassment, discredit, and stigmatization of individuals or social groups based on particular attributes. In this line, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, through its General Recommendation No. 15 on how to Combat Hate Speech (ECRI 2016), specified that it can be motivated by reasons of race, color, descent, national or ethnic origin, ideology, religion, and other personal characteristics or conditions. For its part, the Ministry of the Interior of Spain, collecting the recommendations launched by the European Union, in its Report on the Evolution of Hate Crimes in Spain (Ministry of the Interior of Spain 2021), includes a total of 11 categories of discrimination to classify crimes committed against vulnerable audiences, including racism, xenophobia, and discrimination based on religious beliefs or practices, where Islamophobia would mainly fit. Nevertheless, all these types of intolerance usually converge and are difficult to distinguish (Grosfoguel 2014; Gómez 2019).

The study of hate speech online, especially on Twitter, has been of great interest in recent years. There are several studies in which online hate speech was studied from a linguistic approach, confirming the importance of content on social platforms for the study of this phenomenon. In some of these works, relevant methodological aspects were identified around the categories (Salado 2022); in others, hate was studied around periods of time established from events that triggered public order problems, such as the migration crisis in Ceuta (Spain) in May 2021 (Román-San-Miguel et al. 2022), or with regard to a gender bias associated with current political figures (Alfonso et al. 2022), concluding that misogynistic speech is more prevalent than hate speech associated with political issues. Thus, the study of this phenomenon on Twitter becomes relevant. The authors of this paper, aware of this problem, have also dedicated the last few years to the study of toxic, polarized, and hate speech on social media, especially on Twitter. Accordingly, they have developed automatic detectors of hate speech spread on Twitter for ideological reasons (Amores et al. 2021), for reasons of gender and sexual orientation (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2021a), and for reasons of racism and xenophobia (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2022a). In one of the most extensive studies carried out with one of these detectors, the authors analyzed racist and xenophobic speech on Twitter in countries across Europe (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2022b). This made it possible to verify that the Spanish case is not special, but that toxic and anti-immigration messages are spread in almost all countries on this social platform, which are often a reaction to news events that generate media impact.

Although most users in this social media have a very specific profile, Twitter has always been a platform in which users organically and freely expose their feelings, thoughts, values, and opinions without any kind of control (Chaudhry 2015). This platform is, in this way, a huge open dataset of public opinion on all kinds of issues, which includes polarized and intolerant speeches that are freely expressed. It should be noted that Twitter has maintained just over four million active users in Spain during the last 8 years, according to Statista (2022). There was only a slight increase in 2017 and 2018, when this figure approached five million, to then decrease again. The platform offers a broad overview of human behavior online, being a social network in constant evolution, which makes it an inexhaustible source of information and data for communication research, specifically in cases of numerical analysis with large amounts of data (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2021b). Moreover, ease of access to its data has allowed the development of different tools and methods of analysis that facilitate the task of understanding social and political dynamics on the platform.

To combat this increase in hate speech, on 18 March 2021, the Secretary of State for Migration of the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migration of Spain presented the Protocol to Combat Illegal Hate Speech Online (Secretary of State for Migration 2021). The highlight of the plan was a daily monitoring exercise of the main social media platforms to highlight cases of hate speech. According to this tracking, Islamophobia-related hate speech made up 12.3% of all recorded hate speech in the months of January and February, 11.4% in March and April, 14.7% in May and June, 14.5% in July and August, 9.5% in September and October, and 14.1% (with an increase of 4.6% compared to previous years) in the months of November and December.

1.2. Muslim Community and Islamophobia in Spain

According to the Demographic Study on Muslim Fellow Citizens (Islamic Commission of Spain 2022), although Islam is one of the minority religions in the country, it represents around 4% of the population (just over two million people). Taking national origin into account, the Spanish and Moroccans consolidate the two blocks with the largest number of Muslims in the country, in addition to Pakistanis, Senegalese, and Algerians, among others. Taking this into account, the Muslim community in Spain is considered to be very diverse, in terms of both ethnicity and religious practices. In Spain, Muslims have the right to practice their religion freely and are guaranteed the protection of their religious, cultural, and linguistic rights. In addition, there are numerous mosques and Islamic cultural centers throughout the country, and some municipalities have granted land for the construction of mosques. However, the Muslim community in Spain has also faced problems such as discrimination and stigma, especially after the terrorist attacks of March 2004 in Madrid or August 2017 in Barcelona, which were perpetrated by Islamic extremists. These types of events that draw attention to the Muslim population have acted as a trigger for intolerance toward this community, unleashing Islamophobic attacks and misinformation campaigns. In fact, there are numerous studies that showed a predominance of negative frames of Islam, frequently representing Muslims (both natives and immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East) as a threat to security (identifying them as terrorists, criminals, thieves, and/or rapists), an economic burden, or a symbolic threat to the cultural and religious identity of Western countries (such as Spain) (e.g., Amores et al. 2019, 2020; Greenwood and Thomson 2020; Hafez 2014; Kallis 2018; Lenette and Cleland 2016; Valdez-Apolo et al. 2019; Wodak 2021). One of the discursive strategies most used by media and politicians who spread Islamophobic discourses, often replicated by users on social media such as Twitter, is to associate the Muslim community with immigration, more specifically with illegal immigration. Accordingly, what is achieved is to convey to public opinion the idea that Muslims are all foreigners (and that there are no Spanish Muslims, for example) and, furthermore, that they are criminals, beginning by identifying them as “nonlegal” persons in the country (Cheddadi 2020).

According to Larsson and Sander (2015), Islamophobia is defined as any action or behavior toward an individual or object that the actor identifies as Muslim/Islamic, which is based on fear, hostility, and/or hatred of Islam as a religious and/or cultural system and the bearers of that system. Undoubtedly, Islamophobia, like any other expression of discrimination and hate, accumulates within its historical baggage and transcends borders and social sectors, thus requiring an intersectional vision that considers the multiple layers that make it up (Grosfoguel 2012). It is important to understand that Islamophobia is a specific form of discrimination and prejudice toward Muslims and Islam in general, which can have religious, cultural, racial, and xenophobic manifestations. Since the Islamic religion is usually practiced by people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, Islamophobia can be based on racial or ethnic perceptions, as well as the belief that Muslims are a threat to the security or culture of the society in which they live (Galindo-Calvo et al. 2020). However, it is important to keep in mind that discrimination and prejudice can have different forms and objectives. For example, racism may be based on the perception of the racial superiority of a particular and dominant group, while Islamophobia may be based on the perception that Muslims pose a threat to society’s security or culture. Therefore, not all racist behavior is automatically Islamophobic, and not all Islamophobic behavior is automatically racist or xenophobic. It is essential to understand that Islamophobia and racism are complex and multifaceted phenomena that must be carefully analyzed in order to combat them effectively. Furthermore, it is important to note that Islamophobia is not an exclusive phenomenon of the political right or of extremist groups. There are also Islamophobic positions within the political left (Gil-Benumeya 2021) and feminist movements (Adlbi-Sibai 2012), which criticize Islam for its alleged misogyny and oppression of women. In both cases, this is an oversimplification and biased reality, which does not consider the diversity of practices and opinions within the Islamic world.

Thus, it is crucial to establish an overview of the general representation of the Muslim community in Spain, identifying the most predominant sentiments and the issues with which they are associated. This characterization of Islam makes it possible to identify the main discourses with which Spanish public opinion treats or identifies this group, providing a context to situate Islamophobic speech against other existing perceptions of the Muslim community. In this way, the main objective of this work was to identify the predominant latent topics and sentiments of messages related to the Muslim population published on Twitter in Spain from 1 January 2015 to 1 January 2023.

Considering these premises and taking into account the data presented in the Report on intolerance and discrimination toward Muslims in Spain (OBERAXE 2020), where it was concluded that there is a high level of rejection and discrimination toward the Muslim community spread throughout the Spanish territory, it is expected that the analysis of the conversation about Islam and the Muslim population that takes place on Twitter in Spain can yield indicators that allow characterizing and quantifying the Islamophobic rejection. For this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

The most frequent words in the conversation about Islam and the Muslim community on Twitter between 2015 and 2023 in Spain and in Spanish are mostly negative and potential indicators of Islamophobia.

H2.

The predominant underlying topics in the conversation about Islam and the Muslim community on Twitter between 2015 and 2023 in Spain and in Spanish are mostly negative and potential indicators of Islamophobia.

H3.

The predominant sentiments in the conversation about Islam and the Muslim community on Twitter between 2015 and 2023 in Spain and in Spanish are predominantly negative.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The sample used for this study contained a total of 190,320 tweets about Islam and the Muslim community in Spanish published in Spain between 1 January 2015 and 1 January 2023. Twitter was chosen to analyze the conversation about the Muslim community in Spain due to the potential to study public opinion in a noninvasive way (Arcila-Calderón et al. 2017). It is true that this is not a representative platform for all citizens, since the audience in terms of active users has been reduced in recent years, and since most users have a very specific profile. However, it continues to be a digital platform in which users organically and freely expose their thoughts, values, judgments, and opinions, under the disinhibition that anonymity and the perception of addressing a captive audience give them (Chaudhry 2015). The platform is, in this way, a huge open dataset of feelings and opinions on all kinds of issues, which includes intolerant and discriminatory speeches that are freely expressed and without the barriers that offline environments often present. The period selected for the analysis of the messages published is related to the worsening of the migration crisis in 2015 (UNHCR 2016), with the Syrian Arab Republic and Afghanistan being the main countries of origin of refugees and migrants arriving Europe. The date of the attacks in Barcelona and Cambrils on 17 August 2017, claimed by Daesh, is also considered. It is worth noting that the number of active Twitter users during the time chosen for the data collection remained considerably stable above four million (Statista 2022). The data download was conducted through the Twitter API v.2 using the Python programming language and the Tweepy library. Specifically, the search terms used in the query were the following: islam, islámico/a/os/as, islamista/s, Corán, Alá, musulmán/a/es/as, marroquí/es, moro/a/os/as, Yihad, árabe/s, Mahoma, mezquita, hiyab, hijab, velo, and burka (in English: Islam, Islamic, Islamist/s, Koran, Allah, Muslim/s, Moroccan/s, Moor/s, Jihad, Arab/s, Muhammad, Mosque, hiyab, hijab, veil, and burqa). In addition, we used a geolocation filter to ensure that all the tweets collected had been published in Spain, as well as a language filter to ensure that they were written in Spanish. A filter was also used to discard all the retweets and replies, thus only collecting the original messages. One of the metrics collected with the tweets was the number of retweets of each of those messages; hence, it was possible to analyze the impact in terms of interaction generated from the conversation without having the retweeted messages. In this way, we collected all the original tweets geolocated in Spanish territory and in the Spanish language that contained the searched key terms and that had been published in the last 8 years, together with their associated metadata (including the count of retweets, replies and likes). After the download, the dataset was cleaned, rejecting all duplicate or repeated messages, as well as those that did not contain textual information (tweets with only emoticons, links, or empty content).

2.2. Word Frequency Distribution

Having collected and cleaned the dataset of tweets about Islam and the Muslim community, the first step was to apply basic natural language processing (NLP) techniques to obtain the word frequency distribution (Collobert et al. 2011). For this analysis, different Python libraries were used, such as Numpy or the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). The study of the most frequent words in the sample was used as a previous step for the identification of underlying topics, since it offered valuable exploratory information that is useful for a better interpretation of the results of the subsequent topic modeling. In addition, this analysis by itself already allows us to deduce what topics the conversation about Islam in Spain and in Spanish is predominantly about, observing the most frequent words. The first step to correctly carry out NLP techniques was the identification of tokens (i.e., the basic units), typically simple words or short sentences, into which text can be deconstructed for later analysis. The next step was to remove the stop-words, which are very frequent and common words that do not give relevant information, such as articles or prepositions. Punctuation marks, accents, and web links were also removed to avoid repetition of terms and obtain homogeneous and coherent findings. Lastly, we obtained the most repeated terms and their distribution, which helped decide how many topics were to be retrieved.

2.3. Topic Modeling

Subsequently, topic modeling was used to identify the main latent topics in the sample of tweets about Islam and the Muslim community in Spain. This computational text-mining technique is one of the most widely used to analyze the most predominant underlying topics in large datasets (Karami et al. 2020). Considering this, the technique was selected because it is the most efficient way to explore and extract the main latent issues that are dealt with in the collected messages, considering the infeasibility of carrying out a content analysis on such a large dataset. To execute this analysis, the LDA algorithm was used. This is the most common tool for the automatic detection of topics in a set of documents (Grimmer and Stewart 2013). Using this technique, topics are detected through automatic pattern identification in the presence of competing word groups (Jacobi et al. 2016). In this case, in addition to NLTK, the following Python libraries were used: pandas (used for data analysis), Gensim (used for topic modeling), and pyLDAvis (used to display inferred topics in interactive maps). Before running the analysis, in this case, it was also necessary to convert all text to lowercase and remove punctuation marks, double spaces, and stop-words, to achieve a higher level of consistency in the topics identified. After this cleaning process, internal coherence values were extracted, which made it possible to decide the total number of topics that should be inferred. Subsequently, the pyLDAvis library allowed us to print interactive visualization maps to visually explore the modeling results, which also helped to more reliably select the number of latent topics to detect. With all this, we finally decided to model a total of five topics, since it was the number that seemed most consistent according to the visualizations, and the number that presented the greatest internal consistency (0.364). Next, a manual validation was carried out, exploring the most representative tweets of each identified topic or in which the different topics were most salient.

2.4. Sentiment Analysis

Lastly, we tried to identify latent sentiments in the sample using SentiStrength, an open-source tool that allows automatic sentiment analysis from lexical dictionaries (Thelwall et al. 2011). In the same way as with topic modeling, we decided to carry out an automated sentiment analysis considering the reliability of this technique in large amounts of data and given the infeasibility of manually carrying out an analysis of this type in such a large sample. Specifically, SentiStrength rates the relevance and presence of negative words (from −1 to −5) and positive words (from +1 to +5) in each of the analyzed texts. The sum of these two values indicates the overall sentiment of the tweet in terms of language. To report the global results of latent sentiments, the total average of the coefficients obtained was extracted, as well as the percentages of all the tweets with positive sentiment (from +5 to +1), of all the tweets with negative sentiment (from −1 to −5), and of all neutral tweets (0), i.e., merely informative tweets.

3. Results

First, at an exploratory level, it should be noted that, as expected, most of the tweets analyzed were published in the capital of Spain, Madrid (n = 14,156), and in Barcelona (n = 5942), the two most populated provinces of the country. The remaining Spanish provinces with the highest number of tweets about Islam and the Muslim community in Spanish in the period analyzed were Seville (n = 3624), Malaga (n = 2826), Valencia (n = 2779), Córdoba (n = 2030), Granada (n = 1897), Murcia (n = 1572), Zaragoza (n = 1537), and Bilbao (n = 1469). However, when extracting the rate of tweets per 100,000 inhabitants, the order differed. In this case, the 10 provinces that presented the greatest number of messages about Islam in relation to their population were as follows: Córdoba, with 261.40 messages per 100,000 inhabitants; Madrid, with 207.18; Granada, with 203.49; Seville, with 184.62; Valladolid, with 176.32; Almeria, with 166.89; Malaga, with 164.07; Zaragoza, with 160.19; Asturias, with 151.58; Valencia, with 106.85. Observing both the total frequencies and the rate per 100,000 inhabitants, it is possible to highlight the important presence of Andalusian provinces (the southern region of Spain with the greatest influence of migration from North Africa, especially from Morocco), together with the Spanish capital, and other provinces in the south of the peninsula that also constitute autonomous communities, such as Valencia and Murcia.

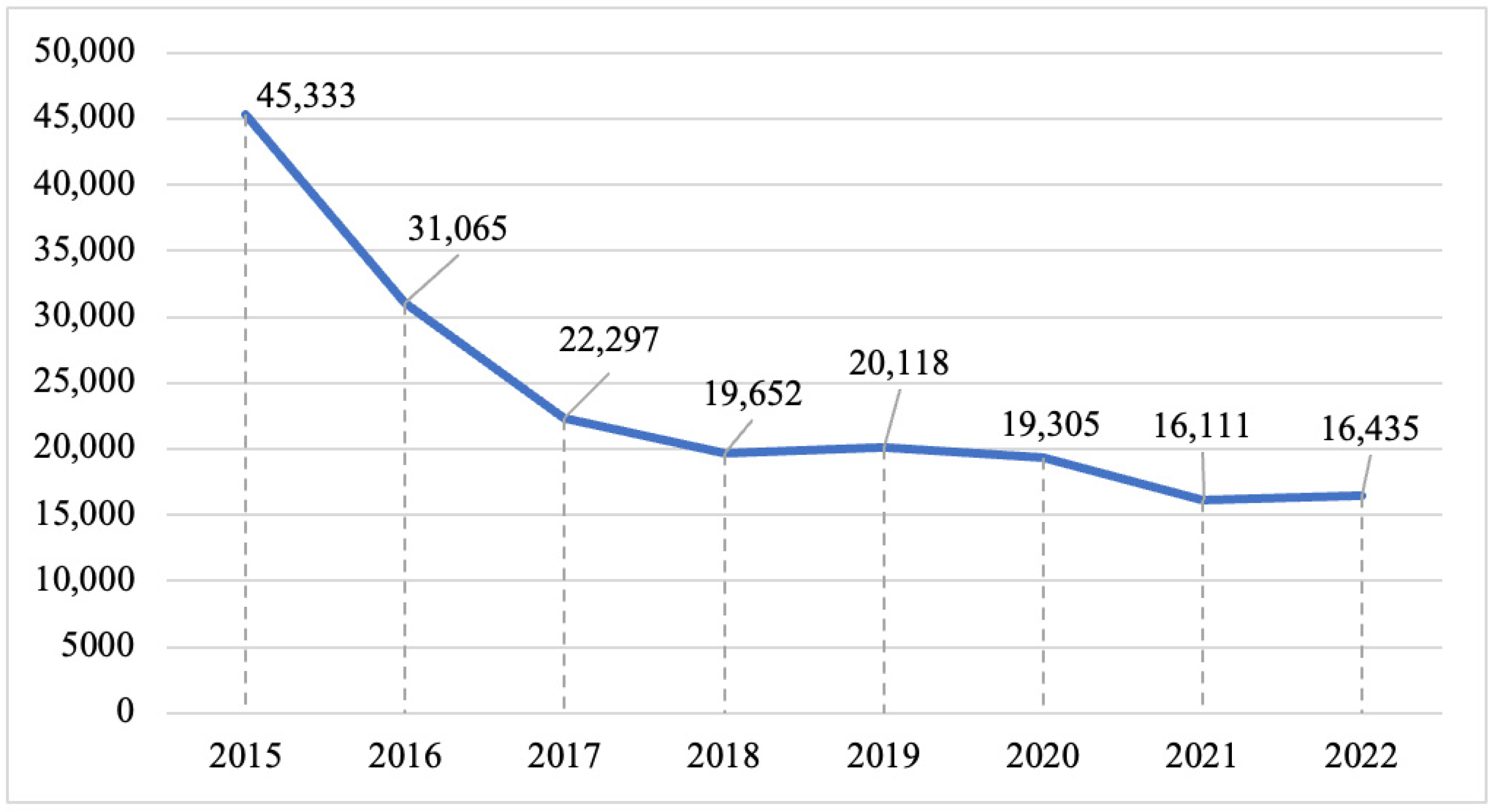

Regarding the frequency of the messages collected throughout the period analyzed from the keywords indicated above, it is worth noting a relatively constant reduction in the number of tweets about Islam published in Spain in Spanish since 2015, the year in which 45,333 messages were published, until 2022, the year in which 16,435 messages were published. This temporal evolution of the frequency of messages about Islam in Spain in Spanish can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Frequency of tweets about Islam in Spain in Spanish since 2015.

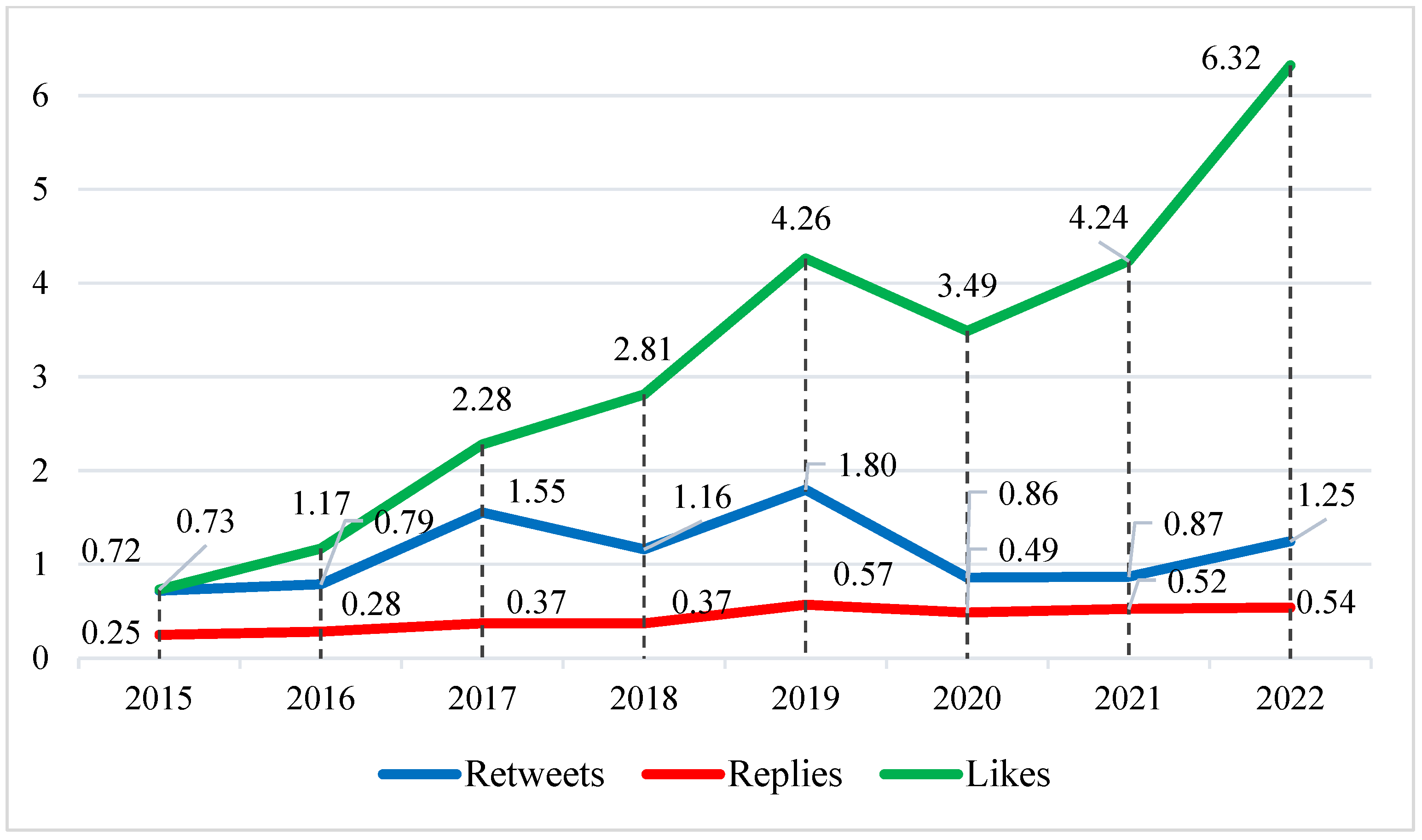

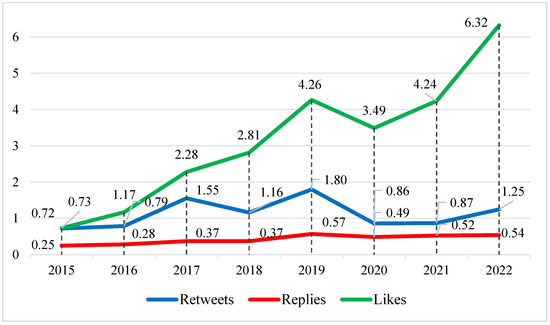

On the other hand, exploring the public metrics that indicate the impact of the tweets in the sample, it can be observed that, while the average number of retweets and replies received by these messages was considerably low in general terms throughout the period analyzed, in the case of likes, a relatively constant increase was observed from 2015, the year in which the average number of likes was 0.73, up to 2022, the year in which this average increased to 6.32. This temporal evolution of the public metrics of tweets about Islam in Spain in Spanish can be seen in Figure 2. However, despite these general averages, in the total sample, there were 471 tweets with more than 100 likes and 28 with more than 1000 likes, 204 tweets with more than 100 retweets and nine with more than 1000 retweets, and 17 tweets with more than 100 replies.

Figure 2.

Average public metrics of tweets about Islam in Spain in Spanish since 2015.

3.1. Most Frequent Words in Tweets about Islam and the Muslim Community in Spain and in Spanish since 2015

The application of natural language processing techniques allowed us to extract the most repeated value words in the dataset with tweets about Islam and the Muslim population published in Spain in Spanish during the last 8 years. To carry out this analysis, firstly, a total of 853 stop-words were extracted, i.e., terms that were too common or did not add any value. Secondly, the analysis was filtered, selecting exclusively the objects or nouns, i.e., words that offer more valuable information about the sample. In this way, the 20 most frequent and predominant words found in the dataset were the following: (“moro”, 17,975), (“mezquita”, 17,035), (“árabe”, 13,082), (“islam”, 12,169), (“velo”, 8817), (“córdoba”, 8270), (“españa”, 5308), (“musulmán”, 5225), (“alá”, 5134), (“catedral”, 4922), (“madrid”, 4539), (“mierda”, 4105), (“gente”, 3876), (“calle”, 3716), (“mundo”, 3541), (“mahoma”, 3481), (“burka”, 3319), (“dios”, 2973), (“país”, 2803), (“mujeres”, 2801); in English: (“moor”, 17,975), (“mosque”, 17,035), (“arabic”, 13,082), (“islam”, 12,169), (“veil”, 8817), (“cordoba”, 8270), (“ spain”, 5308), (“muslim”, 5225), (“allah”, 5134), (“cathedral”, 4922), (“madrid”, 4539), (“shit”, 4105), (“people”, 3876), (“street”, 3716), (“world”, 3541), (“mohammed”, 3481), (“burqa”, 3319), (“god”, 2973), (“country”, 2803), (“women”, 2801).

As can be seen, most of these terms refer directly to the Islamic religion and culture, as well as to the Muslim community. However, there are other frequent words that allude to the country, to the capital of Spain, to the citizens, or, more specifically, to women, which may be related to the frequent identification of Islam as a macho religion and culture. In addition, some of these most frequent words can be considered clear indicators of negative sentiments or rejection of this community, such as “mierda” (in English: “shit”) or “moro” (in English: “moor”), the most repeated word, which is a common and frequently derogatory term used in Spain to refer to Moroccan people. However, even so, H1 cannot be confirmed, since the words that are potentially indicative of Islamophobic rejection were minimal, with respect to the remaining words, which a priori did not indicate a specific sentiment on their own and were mostly descriptive.

3.2. Predominant Topics in Tweets about Islam and the Muslim Community in Spain and in Spanish since 2015

After obtaining the frequency distribution of the collected tweets, topic modeling was performed to automatically detect the main underlying topics in the conversation about Islam and about the Muslim community that took place on Twitter in Spain and in Spanish since 2015. For this, the level of coherence was measured, comparing several models with 20 words for each topic. Eventually, it was decided that the appropriate number of topics to model was 5. After removing the stop-words once more, the topics were detected and validated exploring sample tweets for each. The most predominant topics found are described below.

Topic 1. Information about events and incidents related to the Arab world and the Muslim community, e.g., the attack against the French satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo, news about the Syrian civil war, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and the terrorist attacks committed in Barcelona in 2017. The prevailing sentiment was neutral. The main words of this topic were as follows: 0.040*”moro” + 0.012*”madrid” + 0.006*”dias” + 0.005*”nuevo” + 0.004*”gran” + 0.004*”paris” + 0.004*”charliehebdo” + 0.003*”siria” + 0.003*”campo” + 0.003*”atentado” + 0.003*”policia” + 0.003*”granada” + 0.003*”muertos” + 0.003*”terrorista” + 0.002*”rey” + 0.002*”viva” + 0.002*”eeuu” + 0.002*”israel” + 0.002*”bomba” + 0.001*”negro”); in English: (0.040*”moor” + 0.012*”madrid” + 0.006*”days” + 0.005*”new” + 0.004*”great” + 0.004*”paris” + 0.004*”charliehebdo” + 0.003*”syria” + 0.003*”field” + 0.003*”attack” + 0.003*”police” + 0.003*”granada” + 0.003*”dead” + 0.003*”terrorist” + 0.002*”king” + 0.002*”longlive” + 0.002*”usa” + 0.002*”israel” + 0.002*”bomb” + 0.001*”black”).

Topic 2. Information of a more political and ideological nature about the Arab and Islamic world. The messages referred to politicians and parties, as well as journalists and media with a strong editorial line. Some messages alluded to a supposed Islamic invasion and the need to reinforce the borders, as well as the supposed threat (mostly symbolic) that the Arab community poses to Spain and mainly to Catalonia (since it is considered that this region is supposedly favoring the immigrants of Arab origin and especially allowing the supposed Islamic invasion in the country). Islamophobic or anti-Islam messages targeted progressive and left-wing parties and politicians and held them accountable for this alleged invasion and the alleged threats it represents. On the other hand, messages of support for the Muslim community pointed to the most conservative parties and politicians for their xenophobic and intolerant ideology, policies, and messages and held them responsible for the intolerant and Islamophobic discourses spread on social media. These messages also empathized with displaced persons of Arab origin, providing arguments to support or accept this community. The average sentiment that predominated was neutral. The words with the greatest weight in this topic were as follows: (0.025*”mahoma” + 0.005*”montana” + 0.002*”lucha” + 0.002*”arabia” + 0.002*”hebdo” + 0.002*”numero” + 0.002*”saudi” + 0.002*”verano” + 0.002*”valla” + 0.002*”cataluna” + 0.002*”catalanes” + 0.002*”gente” + 0.002*”abrazo” + 0.002*”curioso” + 0.001*”alegria” + 0.001*”beso” + 0.001*”muerte” + 0.001*”revista” + 0.001*”ataques” + 0.001*”hermanntertsch”); in English: (0.025*”mohammed” + 0.005*”mountain” + 0.002*”struggle” + 0.002*”arabia” + 0.002*”hebdo” + 0.002*”number” + 0.002*”saudi” + 0.002*”summer” + 0.002*”fence” + 0.002*”catalonia” + 0.002*”catalans” + 0.002*”people” + 0.002*”hug” + 0.002*”curious” + 0.001*”joy” + 0.001*”kiss” + 0.001* “death” + 0.001*”magazine” + 0.001*”attacks” + 0.001*”hermanntertsch”).

Topic 3. Messages that relate the Muslim community to crime and terrorism. Messages that identify Muslims as a realistic threat, primarily criminals, rapists, and terrorists, as well as a symbolic threat to the cultural and religious identity, the values and principles of Spain and Europe, and the Western world by extension. The prevailing sentiment was negative. The most representative words of this topic were as follows: (0.035*”islamico” + 0.028*”islam” + 0.026*”arabe” + 0.012*”musulman” + 0.008*”yihad” + 0.006*”espana” + 0.005*”coran” + 0.005*”terrorismo” + 0.005*”religion” + 0.004*”musulmanes” + 0.003*”mujeres” + 0.003*”europa” + 0.003*”isis” + 0.003*”guerra” + 0.002*”libertad” + 0.002*”terroristas” + 0.002*”occidente” + 0.002*”cristianos” + 0.002*”yihadistas” + 0.002*”odio”); in English: (0.035*”islamic” + 0.028*”islam” + 0.026*”arab” + 0.012*”muslim” + 0.008*”jihad” + 0.006*”spanish” + 0.005*”quran” + 0.005*”terrorism” + 0.005*”religion” + 0.004*”muslims” + 0.003*”women” + 0.003*”europe” + 0.003*”isis” + 0.003*”war” + 0.002*”freedom” + 0.002*”terrorists” + 0.002*”west” + 0.002*”Christians” + 0.002*”jihadists” + 0.002*”hate”).

Topic 4. Trivial and ironic random messages that allude to users or groups in the Muslim community or make some kind of reference to elements of the Islamic world, but do not provide or transmit particularly relevant information. These were mostly messages shared between members of the Muslim community itself or related and close people. The prevailing sentiment was positive. The most predominant words of this topic were as follows: (0.143*”ala” + 0.008*”velo” + 0.007*”mierda” + 0.007*”hoy” + 0.007*”dia” + 0.007*”calle” + 0.006*”mañana” + 0.005*”puta” + 0.004*”siempre” + 0.004*”burka” + 0.003*”ano” + 0.003*”feliz” + 0.003*”noche” + 0.003*”vida” + 0.003*”final” + 0.003*”semana” + 0.002*”tarde” + 0.002*”puto” + 0.002*”hora” + 0.002*”anos”); in English: (0.143*”wing” + 0.008*”veil” + 0.007*”shit” + 0.007*”today” + 0.007*”day” + 0.007*”street” + 0.006*”tomorrow” + 0.005*”whore” + 0.004*”always” + 0.004*”burqa” + 0.003*”year” + 0.003*”happy” + 0.003*”night” + 0.003*”life” + 0.003*”end” + 0.003*”week” + 0.002* “afternoon” + 0.002*”fucking” + 0.002*”hour” + 0.002*”years”).

Topic 5. Messages focused especially on the religious and cultural aspect of Islam and its possible confrontation or incompatibility with the Christian religion and culture. Some messages tried to position the Christian Church as morally superior to the Islamic religion, although others emphatically rejected both religions due to their practices and social implications, showing secularism as the only valid option. Messages referring to migration from the Middle East as an Islamic invasion were repeated, in this case representing it mostly as a threat to the Christian and democratic values of Western Europe. Reference was also made to certain conservative parties in Spain and anti-immigration programs and policies as the only solution, against the tolerant policies of the progressive parties. The prevailing sentiment was negative. The most representative words of this topic were as follows: (0.047*”ala” + 0.032*”mezquita” + 0.021*”cordoba” + 0.007*”dios” + 0.007*”casa” + 0.007*”gente” + 0.005*”iglesia” + 0.004*”grande” + 0.004*”cara” + 0.004*”cama” + 0.004*”catedral” + 0.003*”culo” + 0.003*”apropiaciones” + 0.003*”vida” + 0.002*”verdad” + 0.002*”mala” + 0.002*”amor” + 0.002*”paz” + 0.002*”pp” + 0.002*”andalucia”); in English: (0.047*”wing” + 0.032*”mosque” + 0.021*”cordoba” + 0.007*”god” + 0.007*”house” + 0.007*”people” + 0.005*”church” + 0.004*”big” + 0.004*”face” + 0.004*”bed” + 0.004*”cathedral” + 0.003*”ass” + 0.003*”appropriations” + 0.003*”life” + 0.002*”truth” + 0.002*”bad” + 0.002*”love” + 0.002*”peace” + 0.002*”pp” + 0.002*”andalusia”).

Observing these five underlying topics found, the most predominant in the sample, H2 could not be totally confirmed either, since these were not mostly negative. Only two of these topics were potential indicators of a possible Islamophobic rejection, more or less explicit, but the rest were mostly neutral, simple informative messages frequently spread by media or politicians, or even positive, trivial messages shared by random users, often members of the Muslim community in Spain or relatives.

3.3. Predominant Sentiments in Tweets about Islam and the Muslim Community in Spain and in Spanish since 2015

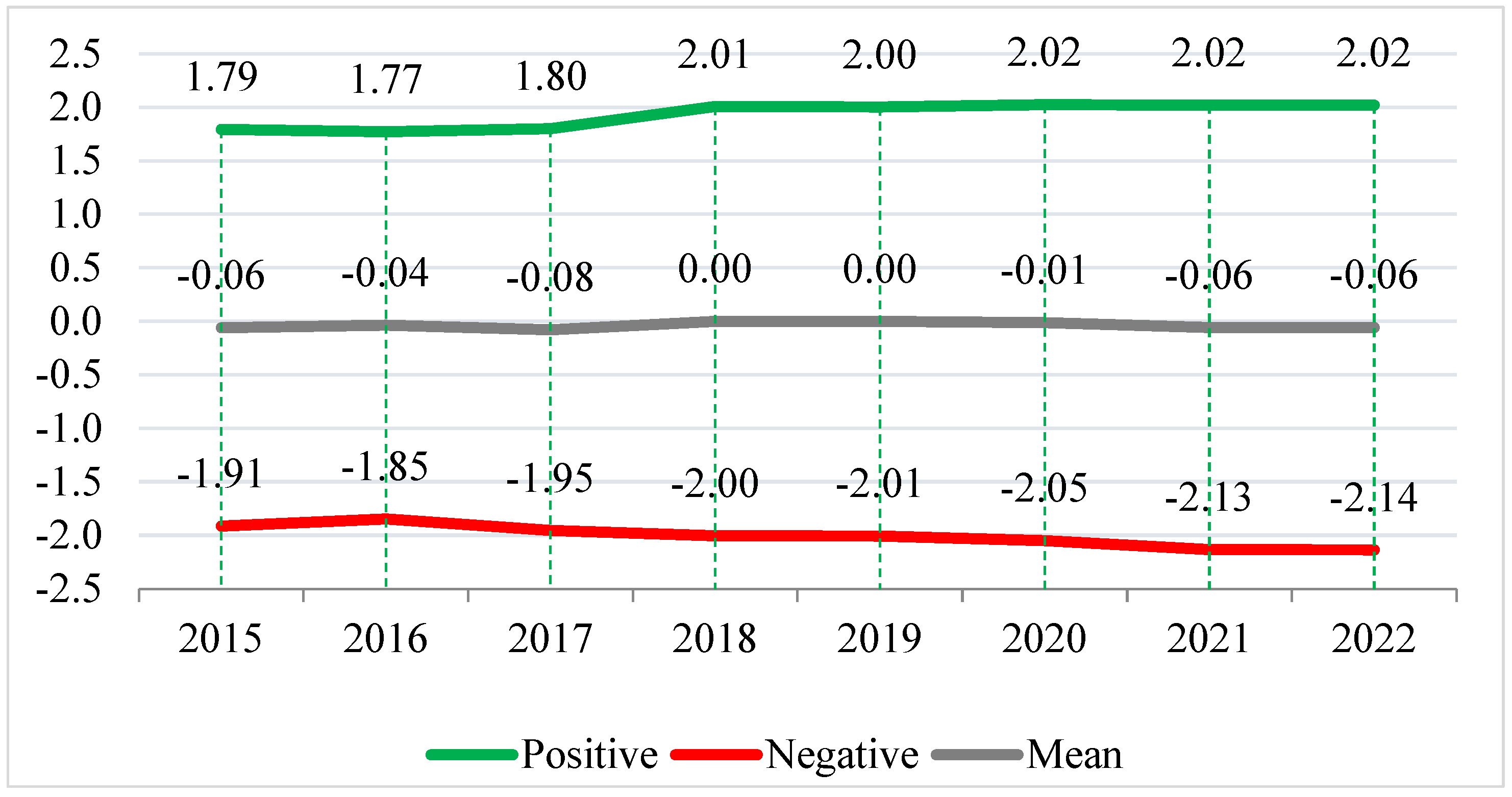

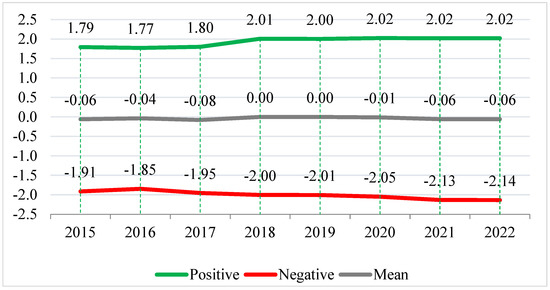

Lastly, using the SentiStrength tool, we carried out a sentiment analysis with the total sample, as well as a longitudinal analysis by years, to observe the temporal evolution of the predominant sentiments. Considering the 190,320 cleaned and analyzed tweets, a total of 63,123 messages had a predominantly positive latent sentiment (33.17% of the total), and 58,196 tweets had a predominantly negative latent sentiment (30.58%), while 69,001 messages were completely neutral (36.26%).

On the other hand, at a general level, the mean of the positive sentiments in the entire sample was 1897, while the mean of the negative sentiments was −1978, which indicates that, although there were more messages with a predominantly positive latent sentiment, the messages in which the negative sentiment predominated were relatively more pronounced and salient. Furthermore, as indicated, most of the tweets were neutral or did not have a pronounced latent sentiment that could be identified. With this, H3 could be relatively confirmed, since the average global sentiment detected in the entire sample was −0.041, which indicates a negative trend, albeit very close to neutrality.

At a longitudinal level, throughout the analyzed years, no significant changes were observed; the average sentiment detected was always neutral with a slightly negative trend, oscillating between 0, the most positive average, in years such as 2018 and 2019, and −0.081, the most negative average, detected in 2017. Figure 3 shows this evolution of the average sentiment throughout the period analyzed.

Figure 3.

Average latent sentiments in tweets about Islam in Spain in Spanish since 2015.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we analyzed using computational techniques the conversation around Islam and the Muslim community that took place on Twitter in Spain and in Spanish since 2015, trying to explore if the most frequent words, the main underlying topics, and the latent sentiments could be indicators of potential Islamophobic hatred and to what extent. On the basis of a review of the little existing literature on this specific topic, i.e., the general conversation around Islam on social media, three hypotheses were established that affirmed that both the most frequent words and the predominant underlying topics and the latent sentiments, at a general level, would mostly be indicators of Islamophobia. However, these hypotheses could not be totally confirmed, except for the third one, dedicated to latent sentiments. Hypothesis 3 could be confirmed but with great caution, as, although the overall trend of average sentiment was negative, this was because those negative messages had a much more pronounced sentiment than neutral or positive messages. However, at the level of the percentage of messages or observed frequency, it was determined that the number of neutral and/or positive messages was greater than the number of negative messages. With this, the general conclusion would be that the conversation around Islam on Twitter in Spain since 2015 was mostly neutral, since most of the messages were simply informative, and that the relationship between positive and negative messages was balanced, since the percentages were quite even. Therefore, although the average coefficient was negative, it could not be definitively concluded that messages with a negative sentiment predominated or that these messages are indicators of some type of Islamophobic rejection.

Regarding the most frequent words found in the sample, most were descriptive terms related to the Islamic religion and culture, as well as to the Muslim community. It is true that some of these words could indicate some kind of latent Islamophobic rejection, such as “shit”, “ass”, “whore”, “terrorists”, or, above all, “moor”, which was the most frequent of all. However, these words were not among the most frequent, and they should not be inherently taken as a reliable indicator of a possible Islamophobic rejection or hatred, since words such as “moor” are ambiguous and do not always have a derogatory use in the Spanish context.

A total of five predominant underlying topics were found in the analyzed dataset. Of those, one was more positive, two were mostly neutral, and the other two were mostly negative. These last two could be considered, in a somewhat more reliable way, indicators of Islamophobic hatred or rejection, manifested in a subtle or explicit way. However, although there seems to be an important presence in magnitude, which should serve as an alert to continue paying attention to the Islamophobic hate speech disseminated through social platforms, these more negative topics were generally not predominant. This latest analysis confirmed that the topics and types of messages that predominated in this conversation about Islam in Spain were mostly neutral, of a predominantly informative nature. Regarding the characteristics of the most negative topics found, they seemed to contain messages of rejection of the Muslim community, especially for two main reasons, identifying it as a realistic threat to the public and individual security of Spanish citizens (frequently representing Muslims as terrorists, criminals, murderers, rapists, or thieves), and as a symbolic threat to the cultural and religious identity of Spain and Western Europe, by extension. These are the same negative frames that had already been previously defined and identified in the way immigrants are generally represented in news media and social media (e.g., Amores and Arcila-Calderón 2019; Greenwood and Thomson 2020; Hafez 2014; Kallis 2018; Wodak 2021). In short, on the basis of these supposed threats, messages of support for conservative political parties and demands for anti-immigration measures also formed part of these more negative topics.

On the other hand, at a more exploratory level, an incessant reduction in tweets about Islam and the Muslim community in Spain and in Spanish was detected since 2015. This may be due to the reduction in the number of arrivals and asylum applications in recent years, after the years of greatest migratory pressure during the migration crisis after the Arab springs. It should be noted that 2015 was the year in which the refugee crisis in Europe and the Mediterranean worsened (UNHCR 2016), exponentially increasing migratory pressure, especially from the Middle East and North Africa. In short, once the number of asylum applications registered in the country normalized and stabilized, there was a reduction in media attention to the migration issue (and, with it, to associated cultural and religious issues) in the country, which led the political agenda and public opinion to focus on other issues. Regarding the observed constant increase in likes of tweets about Islam published on Twitter in Spain and in Spanish from 2015, there is no apparent explanation for its cause. One of the reasons that could be speculated is that, after the years of greater migratory pressure and greater media attention to migratory and related issues, as indicated, the number of messages referring to Islam on Twitter was much lower, which may indicate that the users who remained talking about this topic had a greater involvement or engagement on Twitter. This in turn could indicate that, although the conversation was smaller, it was even more politicized. On the other hand, it was also observed that the largest number of tweets about Islam and the Muslim community in Spain in Spanish during the last 8 years were published in the southern provinces of Spain, mostly Andalusian. This may be due to the fact that, in those regions, Castilian is mostly spoken, whereas, in the northern regions, other languages are spoken such as Catalan, Galician, or Basque. Second, this may be due to the great influence of the Arab world in the Andalusian region, due to its history and its proximity to North Africa, which makes it a region that mainly receives Muslim immigrants, especially from Morocco.

Lastly, it is important to point out the limitations of this study and future lines of research. Although the work was extensive and a large sample was collected and analyzed from different perspectives, there were still limitations, especially methodological ones. Firstly, since a geolocation filter was used in the data collection, only some of the messages could be accessed, since not all tweets contain that information. However, this was the only way to have a dataset of messages about the Islamic world published only in Spain. In this sense, it would be very complex to know with certainty the size of the total sample without geolocation filtering, since it would be necessary to distinguish between messages in Spanish published outside of Spain (from Latin American contexts, for example) and those published in Spain. This makes it difficult to know with certainty the representativeness of the study. On the other hand, it should be noted that sentiment analysis and topic modeling are not inherently completely adequate or reliable for analyzing the conversation around Islam and the Muslim community on Twitter. Nevertheless, they served to explore and identify patterns that allow to highlight the magnitude, relevance, and the main topics and characteristics of the messages disseminated on this social platform, especially negative ones, which are mostly indicators of possible Islamophobic rejection. Moreover, these results, as they cover such a large period and sample, can be considered generalizable; thus, they can be extrapolated to other present or future time contexts, to other social platforms, or to other European countries. In the same way, these results can serve as a basis for future studies to analyze separately, specifically, and in greater depth the Islamophobic hate messages spread on Twitter or other social platforms, as well as develop counternarrative strategies. In fact, it would be interesting to continue developing this type of analysis with data extracted from social media in Spain, as well as other European countries, which would allow comparisons to be made. However, these analyses could and should be complemented with other types of methods, both computational and those of a more qualitative nature, aiming to characterize the Islamophobic rejection messages in more depth, as well as identify the main users responsible for these messages and their connections (wherein possible ghost or fake accounts could be participating in those public debates) and the possible effects of these negative messages on society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G.-B., J.J.A. and C.A.-C.; methodology, J.J.A. and C.A.-C.; software, J.J.A. and C.A.-C.; validation, W.G.-B., J.J.A. and C.A.-C.; formal analysis, J.J.A.; investigation, W.G.-B. and J.J.A.; resources, W.G.-B. and J.J.A.; data curation, J.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G.-B. and J.J.A.; writing—review and editing, W.G.-B. and J.J.A.; visualization, J.J.A.; supervision, C.A.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed within the framework of the project “Evaluando Campañas contra el Odio” (ECO), funded by the European Union through the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme (CERV-2022-EQUAL).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their restricted access in only using Twitter’s API.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adlbi-Sibai, Sirin. 2012. Colonialidad, feminismo e islam. Viento Sur 122: 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, Ignacio Blanco, Leticia Rodríguez Fernández, and Sergio Arce García. 2022. Polarización y discurso de odio con sesgo de género asociado a la política: Análisis de las interacciones en Twitter. Revista de comunicación 21: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon Willard. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Boston: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Amores, Javier Jiménez, and Carlos Arcila-Calderón. 2019. Deconstructing the symbolic visual frames of refugees and migrants in the main Western European media. Paper present at the Seventh International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, León, Spain, October 16–18; pp. 911–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, Javier Jiménez, Carlos Arcila-Calderón, and David Blanco-Herrero. 2020. Evolution of negative visual frames of immigrants and refugees in the main media of Southern Europe. Profesional de la Información 29: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, Javier Jiménez, Carlos Arcila-Calderón, and Mikolaj Stanek. 2019. Visual frames of migrants and refugees in the main Western European media. Economics & Sociology 12: 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, Javier Jiménez, David Blanco-Herrero, Patricia Sánchez-Holgado, and Maximiliano Frías-Vázquez. 2021. Detectando el odio ideológico en Twitter. Desarrollo y evaluación de un detector de discurso de odio por ideología política en tuits en español. Cuadernos.info 49: 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Félix Ortega-Mohedano, Javier Jiménez Amores, and Sofia Trullenque. 2017. Análisis supervisado de sentimientos políticos en español: Clasificación en tiempo real de tweets basada en aprendizaje automático. Profesional de la Información 26: 973–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Javier Jiménez Amores, Patricia Sánchez-Holgado, and David Blanco-Herrero. 2021a. Using shallow and deep learning to automatically detect hate motivated by gender and sexual orientation on Twitter in spanish. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 5: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Javier Jiménez Amores, Patricia Sánchez-Holgado, Lazaros Vrysis, Nikolaos Vryzas, and Martin Oller Alonso. 2022a. How to Detect Online Hate towards Migrants and Refugees? Developing and Evaluating a Classifier of Racist and Xenophobic Hate Speech Using Shallow and Deep Learning. Sustainability 14: 13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Patricia Sánchez Holgado, Cristina Quintana Moreno, Javier Jiménez Amores, and David Blanco Herrero. 2022b. Discurso de odio y aceptación social hacia migrantes en Europa: Análisis de tuits con geolocalización. Comunicar 71: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Wouter Van Atteveldt, and Damian Trilling. 2021b. Dossier Métodos computacionales y Big Data en la Investigación en Comunicación. Cuadernos.info 49: I–IV. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, Irfan. 2015. #Hashtagging hate: Using Twitter to track racism online. First Monday 20: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheddadi, Zakariae. 2020. Discurso político de Vox sobre los menores extranjeros no acompañados. Inguruak. Revista Vasca de Sociología y Ciencia Política 69: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collobert, Ronan, Jason Weston, Léon Bottou, Michael Karlen, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and Pavel Kuksa. 2011. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12: 2493–537. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 1997. Recommendation No. R (97) 20 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on “Hate Speech”. Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers. Available online: https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectID=0900001680505d5b (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Del-Fresno-García, M. 2019. Desórdenes informativos: Sobreexpuestos e infrainformados en la era de la posverdad. El Profesional de la Información 28: e280302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI). 2016. ECRI General Policy Recommendation N.° 15 on Combating Hate Speech. Council of Europe. Available online: https://book.coe.int/en/human-rights-and-democracy/7180-pdf-ecri-general-policyrecommendations-no-15-on-combating-hate-speech.html (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Felt, M. 2016. Social media and the social sciences: How researchers employ Big Data analytics. Big Data & Society 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Lara, Cristina, and Carlos Arcila-Calderón. 2023. El discurso de odio islamófobo en las redes sociales. Un análisis de las actitudes ante la islamofobia en Twitter. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación 14: 225–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Calvo, Pablo, Beatriz Jiménez-Roger, Francisco Javier Cantón-Correa, and Maria do Nascimento Esteves-Mateus. 2020. Islamophobia in southern Europe: The cases of Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. In Social Problems in Southern Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Benumeya, Daniel. 2021. El racismo y la islamofobia en el mercado discursivo de la izquierda española. Política y Sociedad 58: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L. 2019. Diccionario de Islam e Islamismo. Rosari: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Keith, and T. J. Thomson. 2020. Framing the migration: A study of news photographs showing people fleeing war and persecution. International Communication Gazette 82: 140–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis 21: 267–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2012. El concepto de «racismo» En Michel Foucault y Frantz Fanon: Teorizar desde la zona del ser o desde la zona del no-ser. Tábula Rasa 16: 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2014. Las múltiples caras de la islamofobia. De Raíz Diversa. Revista Especializada en Estudios Latinoamericanos 1: 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gualda, Estrella, and Carolina Rebollo. 2020. Big Data y Twitter para el estudio de procesos migratorios: Métodos, técnicas de investigación y software. Empiria: Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 46: 147–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Solé, Frederic, Lluís Mas-Manchón, and Toni Aira. 2022. El impacto de la ultraderecha en Twitter durante las elecciones españolas de 2019. Cuadernos.info 51: 223–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Farid. 2014. Shifting borders: Islamophobia as common ground for building pan-European right-wing unity. Patterns of Prejudice 48: 479–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamic Commission of Spain (Comisión Islámica de España). 2022. Estudio Demográfico sobre Conciudadanos Musulmanes. Available online: https://comisionislamica.org/2022/03/14/estudio-demografico-de-la-poblacion-musulmana/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Jacobi, Carina, Wouter Van Atteveldt, and Kasper Welbers. 2016. Quantitative analysis of large amounts of journalistic texts using topic modelling. Digital Journalism 4: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, Aristotle. 2018. The radical right and Islamophobia. In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, pp. 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, Amir, Morgan Lundy, Frank Webb, and Yogesh K. Dwivedi. 2020. Twitter and Research: A Systematic Literature Review Through Text Mining. IEEE Access 8: 67698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Göran, and Åke Sander. 2015. Urgent Need to Consider How to Define Islamophobia. Bulletin for The Study of Religion 44: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline, and Sienna Cleland. 2016. Changing Faces. Creative Approaches to Research 9: 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Interior de España. 2020. Informe Sobre la Evolución de los Delitos de Odio en España (Report on the Evolution of Hate Crimes in Spain). Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/publicaciones-descargables/publicaciones-periodicas/informe-sobre-la-violencia-contra-la-mujer/Informe_evolucion_delitos_odio_Espana_2020_126200207.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Moreno, Joan Manuel Oleaque. 2020. El discurso en positivo de Vox: Los medios difundidos en Twitter por la extrema derecha. Cuadernos AISPI: Estudios de Lenguas y Literaturas Hispánicas 16: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Español del Racismo y la Xenofobia. 2020. Informe sobre la Intolerancia y la Discriminación Hacia los Musulmanes en España. Available online: https://www.inclusion.gob.es/oberaxe/es/publicaciones/documentos/documento_0131.htm (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Román-San-Miguel, Aránzazu, Francisco José Olivares-García, and Salud María Jiménez-Zafra. 2022. El discurso de odio en Twitter durante la crisis migratoria de Ceuta en mayo de 2021. La Revista Icono 14: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salado, Mercedes Ramírez. 2022. Análisis lingüístico del discurso de odio en redes sociales. Visual Review 9: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Estado de Migraciones, Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. 2021. Protocolo para Combatir el Discurso de odio Ilegal en Línea (Protocol to Combat Illegal Hate Speech Online). Available online: https://inclusion.seg-social.es/oberaxe/ficheros/documentos/PROTOCOLO_DISCURSO_ODIO_castellano.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Statista. 2022. Número de perfiles de Twitter en España de 2014 a 2021. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/520056/usuarios-de-twitter-en-espana/#:~:text=En%202021%2C%20el%20número%20total,de%20aproximadamente%204%2C2%20millones (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Thelwall, Mike, Kevan Buckley, Georgios Paltoglou, Di Cai, and Arvid Kappas. 2011. Sentiment strength detection in short informal text. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 62: 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón-Navarro, Jorge, and Andrea Bouzas-Blanco. 2023. Extrema derecha europea en Twitter. Análisis de la estrategia comunicativa de Vox y Lega durante las elecciones europeas de 2014 y 2019. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación 14: 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2016. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/unhcr-global-trends-2015 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Valdez-Apolo, María Belén, Carlos Arcila-Calderón, and Javier Jiménez Amores. 2019. El discurso del odio hacia migrantes y refugiados a través del tono y los marcos de los mensajes en Twitter. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación 6: 361–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2021. From Post-Truth to Post-Shame: Analyzing Far-Right Populist Rhetoric. In Approaches to Discourse Analysis. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Medina, Rocío, Pilar Garrido-Clemente, and Jorge Sánchez-Martínez. 2021. Análisis del discurso de odio sobre la islamofobia en Twitter y su repercusión social en el caso de la campaña «Quítale las etiquetas al velo». Anàlisi 65: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).