Abstract

The founding of the fourteen monasteries that operated for varying lengths of time in Iceland are in most cases known, but their dissolution differs. It is, however, known that none of them were closed due to plagues, natural disasters, or economic crises but rather because of administrative reasons. Five of the monasteries perished within a few decades; however, most of them perished because of political disputes between secular and ecclesiastical powers in Iceland during the thirteenth century. On the other hand, nine of them became highly prosperous but were dissolved following the Lutheran Reformation in the mid-sixteenth century. The truth is that monasticism vanished in Iceland with the closure of the last one in 1551, and their previous occupation was thereby discontinued. Here, an attempt will be made to obtain an overview of their dissolution, but their growth and development were in all cases dependent on the country’s authorities at any given time, ecclesiastical and royal. Still, the circumstances of their dissolutions varied nonetheless between monasteries.

1. Introduction

Fourteen monastic houses operated for varying lengths of time in Iceland during the Middle Ages. Four of them were dissolved early on, mainly because of the political disputes that arose in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries between the island’s secular and ecclesiastical powers. One was moved and reestablished in a new location under a new name. Eight of the monastic houses became highly prosperous, operating for centuries under either Benedictine or Augustinian customs. Moreover, at the end of the fifteenth century, a new Augustinian house was opened in Iceland, and it became the last one to be founded there until recent times. These nine successful monastic houses were dissolved with the Lutheran Reformation in the mid-sixteenth century, the first one in 1539 and the last in 1551.

In Iceland, as elsewhere, the Reformation not only involved a change in religious practice but also a reorganization of the government’s role in ecclesiastical and royal affairs. At the time when the monastic houses were dissolved, Iceland was governed by the Kingdom of Denmark, wherefrom the reform was administrated. The course of events was alike in all provinces of the Danish Crown, which covered Denmark, Norway, Greenland, the Faroes, and Iceland, although with local variations. It is worth noting that no monastic house operated in the Faroes and Greenland at the times of the Reformation. Still, the Danish king had plans to establish schools in the former monasteries in Iceland, as had been the case in Norway and Sweden, but his arrangements failed. The main differences regarding the dissolution of the monastic houses operating under the Kingdom of Denmark may be found in the protest of the last serving Catholic bishop in Northern Europe, Jón Arason. He managed—through his individual resistance—to hinder the institutional destruction that the Reformation thrust upon his own bishopric, Hólar, in Northern Iceland. The dissolution of the four monastic houses within this single bishopric was thus delayed, while all other monasteries belonging to the metropolitan Sees of the Nordic countries (Niðarós, Lund, and Uppsala) were closed. Nevertheless, these four monastic houses in Northern Iceland appear to cease functioning around 1541, when the Lutheran church ordinance was accepted at the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi. Bishop Jón Arason was beheaded in November 1550, and his execution is commonly observed as the ultimate closure of the Catholic Era in Iceland´s medieval history.

In order to explore further the dissolution of the Icelandic monasteries, as will be accomplished in the following, it is necessary to discuss in brief the history of monasticism in Iceland.

2. Monasticism Settles in Iceland

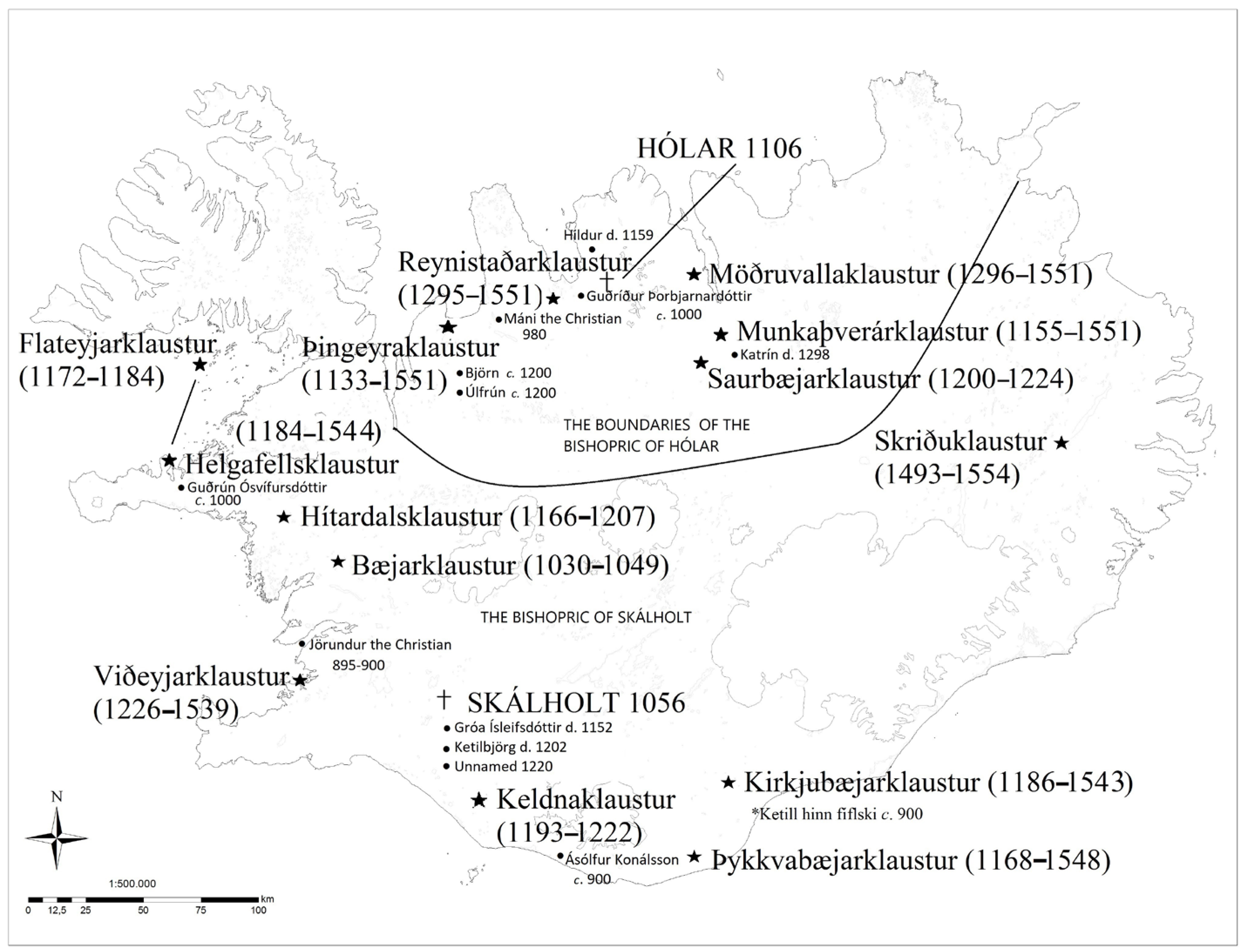

Monastic houses increased rapidly in number during the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Northern Europe. Iceland was certainly not excluded from this expansion. In the twelfth century alone, eight monasteries were established there of either Benedictine or Augustinian orders. Another five of the same orders were established before the end of the fifteenth century (Figure 1). Additionally, two monastic houses—one Benedictine and one Augustinian—began to operate inside the Icelanders’ settlement in Greenland (Kristjánsdóttir 2021, pp. 60–61). This should not come as a surprise, as these two orders were widespread on the Continent throughout the Middle Ages. Indeed, while other orders such as Cistercians, Franciscans, and Dominicans were simultaneously popular in Northern Europe, they never reached the northernmost provinces of the Roman Catholic Church in Iceland and Greenland, most likely because their organizations did not fit into these rural societies as they were (Aston 2001; Clark 2011; Kristjánsdóttir 2021).

Figure 1.

The location and dates of activity of male and female monasteries in Iceland. The map also shows the location and the foundation date of the respective bishoprics in Skálholt and Hólar.

However, the monastic houses Helgafellsklaustur and Þykkvabæjarklaustur appear to have periodically followed the order of St. Victor, which is a suborder of the Augustinians well known in the other Nordic countries (Gunnar Harðarson 2016, pp. 136–42). Skriðuklaustur could have belonged to another suborder of the Augustinians, the Order of the Holy Spirit, as the order was responsible for running hospitals as Skriðuklaustur did (Jakobsen 2021, pp. 74–75). This order was popular in Denmark, particularly in the late fifteenth century, when Skriðuklaustur was founded; however, this house was dedicated to the holy blood, Jesus Christ and the Virgin (Kristjánsdóttir 2012, p. 14). Another monastery, Keldnaklaustur, may have followed the Johannite order as its patron saint was St. John the Baptist. To dedicate monastic houses to St. John was common during the twelfth century in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, when Keldnaklaustur was established, but these houses followed the Johannite Order (KHLM 1962, pp. 599–606; Nyberg 1984, pp. 193–225; McGuire 1988, pp. 20–21; Jakobsen 2021, pp. 73–74). However, very little is otherwise known about Keldnaklaustur because it was closed in 1222 after only a two-decade-long operation (Kristjánsdóttir 2017, pp. 303–5).

Nevertheless, the orders operating in Iceland were products of the close connection of monasticism in the country with its development on the Continent. Moreover, the general expansion of monasticism to Iceland should be attributed to the mission of the Gregorian papacy in the late eleventh century, which aimed to extend its influence up to the northernmost provinces of the Roman Catholic Church. This caused a struggle between royal and ecclesiastical powers, in Iceland as well as throughout the Continent (Jensson 2016, pp. 14–24; Kristjánsdóttir 2023a, pp. 35–40). Still, even earlier, missionaries were sent out to Christianize the people in the North, resulting in their gradual conversion in liaises with local chieftains and kings (Winroth 2012, pp. 112–20, 150–52). One of these missioners was Rudolf, who founded the first monastic community in Iceland, Bæjarklaustur, in AD 1030. However, the running of it failed after two decades. Rudolf left Iceland in 1049 and was set in office as the abbot of Abington Abbey in England (Kristjánsdóttir 2023a, p. 34).

The prerequisites for establishment of an ecclesiastical institution in Iceland were almost non-existent when Bishop Rudolf made his attempt to open a monastic house in this fairly young society. At this point, Iceland belonged to the archbishopric in Hamburg-Bremen—the northernmost territory of the Roman Catholic Church—whereunder it was set with the formal conversion of Icelanders around AD 1000. By then, no bishopric had yet been founded in Iceland. The first was established in Skálholt in 1056, seven years after the dissolution of Bæjarklaustur. It took a while for monasticism to settle in Iceland and it did not happen effortlessly.

What encouraged the Roman Catholic Church to strengthen its authority in Europe’s northernmost fringes was the establishing of the archbishop’s See in Lund, southern Scandinavia, in 1104. The See in Lund also had jurisdiction over the ecclesiastical affairs in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Greenland, and Iceland. It was then the first archbishop of Lund, Asser Thorkilsson, founded the second bishopric in Iceland at Hólar in 1106 and subsequently ordained Jón Ögmundsson as the bishop over it. Archbishop Asser also founded a bishopric in Garðar, Greenland, and ordained a bishop over it too in 1124 (Hugason 2000, pp. 166–68; Jensson 2016, pp. 22–23). Hence, the situation gradually changed, although a century passed from the founding of Bæjarklaustur until a monastic institution gained firm ground for successful operation in Iceland. This was Þingeyraklaustur, founded on the initiative of Bishop Jón, who did not though live to see through to its beginnings (Kristjánsdóttir 2023a, pp. 34–35).

When Iceland’s archbishopric See was moved from Lund to Niðarós in 1153, the expansion of monasticism to the North grew even further, at the same time as the Nordic countries were split between three ecclesiastical entities. The archbishopric of Niðarós had authority over ecclesiastical affairs in Norway—where it was based—as well as Greenland, the Faroes, Orkney, Shetland, the Isle of Man, as well as Iceland (Figure 2), while Denmark remained under the archdiocese of Lund and Sweden was set under the archdiocese of Uppsala. In 1472, the bishoprics in Orkney and Sodor/Isle of Man were moved under the archbishopric of St. Andrews, thereby becoming part of the Scottish Church (see Thomas 2014; Imsen 2021, p. 53). The Archdiocese of Niðarós remained otherwise unaltered until the Reformation in 1537. There were not only shifts in the churchly affairs in Iceland during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries but even changes regarding royal power when Iceland was set under the Norwegian Crown in 1262. This union diminished the role of the Icelandic chieftains who had ruled the country since 930, which was further weakened due to internal struggle, Staðamál, that is, the struggle between royal and ecclesiastical powers in Iceland. This struggle was settled in Norway in 1297 (Kristjánsdóttir 2023a, pp. 35–40).

Figure 2.

The bishoprics of the archbishopric of Niðarós, established in 1153. In 1472, the bishoprics in Orkney and Sodor/Isle of Man were moved under the archbishopric of St. Andrews. The archbishopric of Niðarós was dissolved in 1537.

From the establishment of the Archdiocese of Niðarós in 1153 until 1226, seven new monastic houses were established in the bishopric of Skálholt and two in the bishopric of Hólar (Table 1). Three of them were founded on the initiative of secular chieftains, agitating the ecclesiastical governments in Iceland, as well as abroad. All the monastic houses active at this point faced by then periodic difficulties owing to the internal conflicts, Staðamál. Three of them perished, and one was altered. Moreover, when the internal struggles were settled, two new monasteries were founded, and a final one was founded in the late fifteenth century, when the Catholic Church was still at its peak. All the monastic houses responded, however, to diverse challenges during their time of their operation, but none was as destructive as the Reformation in the sixteenth century.

Table 1.

The monasteries in Iceland, their order, period of running, and closure.

3. Reforming Monasticism in Skálholt Bishopric

Inevitably, when the archbishopric in Niðarós was abolished in 1537, the status of the Roman Church in Iceland was at once weakened. The Danish king, Christian III (in office 1534–1559), had introduced Lutheranism in Denmark the year before, but it was in June 1541 that the Lutheran church ordinance—in a translation of the Danish one by Bishop Gissur Einarsson—was accepted at the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi (DI X n.d., pp. 632–33). Emphasis was placed on strengthening royal power at the same time as Catholicism was banned. Denmark’s adoption of Lutheranism spelled thus the end of any form of monasticism in its provinces, including Iceland. The closing of the Icelandic monastic houses started on Whitsunday 1539 when the agents of the king attacked the monastery in Viðey (Viðeyjarklaustur). The monastery’s buildings were then broken down and desecrated, and the inhabitants were mistreated. The intention was to take the same approach to the monasteries Þykkvabæjarklaustur and Kirkjubæjarklaustur too, but that did not happen (DI X n.d., pp. 444–47, 449–59, 479–80). The Reformation had begun, nevertheless, and the dissolution of the monasteries began with it.

In continuation of the attack, the representative of the Danish king, Claus of Mervitz, handed over the former monastery in Viðey with all its properties to one of those responsible for the attack, Diðrik von Minden. The last Catholic bishop of Skálholt bishopric, Ögmundur Pálsson, was still in office at the time of the attack, but before he was ordained as a bishop in 1521, he had served as the abbot of Viðeyjarklaustur. Thus, he knew the attacked monastery very well. Although the meaning of excommunication was about to vanish with Catholicism, Bishop Ögmundur used his power and excommunicated von Minden for the act (DI X n.d., pp. 449–50, 451–59). However, von Minden was killed later the same year in the upheavals that followed the attack (DI X n.d., pp. 464–65, 481–83). In December 1542, the Danish king ordered that his officials in the country should have their residency in Viðey (DI XI n.d., pp. 179–80). The first one was Pétur Einarsson. He settled as planned in Viðey and converted what was left of the old monastic building, erected new structures, and converted the monastery into a secular residency (DI XI n.d., pp. 138–39).

Viðeyjarklaustur was thus the first Icelandic monastery to be dissolved due to the Reformation. Although the first Lutheran bishop in Iceland, Gissur Einarsson, was not chosen until 1541, he was officially ordained a year later in Denmark, serving the bishopric of Skálholt (DI X n.d., pp. 447–448, 529–531, 533–534). Soon after he was ordained, the remaining monasteries in the Skálholt diocese, Helgafellsklaustur, Þykkvabæjarklaustur, Kirkjubæjarklaustur, and Skriðuklaustur, stopped operating as monastic houses (Table 1).

The representative of the Danish Crown, seneschal Christopher Hvítfelt, stated 4 July 1541 that all monastic properties in Denmark, Norway, and Iceland had been taken over by the king (DI X n.d., p. 640). It may well have been the case to some extent, but not entirely. In some cases, the ultimate closure of the monasteries belonging to the Skálholt diocese seemed to have been delayed for a few years, although it is often unclear on what terms they functioned after 1541.

The course of events in Iceland contrasted with the dissolutions in Denmark and Norway in the sense that they were all taken over by the Danish Crown. For instance, of 33 monastic houses in Norway, 31 were suppressed at the Reformation, but some of them were sold to wealthy people after the crown seized and secularized them. Similarly, several of the Danish monasteries were secularized and converted into schools or hospitals without any monastic presence in them (Ekroll 2019, pp. 166–67; Larsen 2019; Jakobsen 2021, pp. 75–77).

This did not happen in Iceland, although the Danish king certainly had plans to open Latin schools in the former monasteries of the Skálholt diocese. Those plans fell through, as did his plans to open hospitals in all quarters of the country when monasteries with associated public services were discontinued in the country (Ísleifsdóttir 2003, pp. 115–17). King Christian III did, on the other hand, open Latin schools at the bishop´s seats of Skálholt and Hólar (Guttormsson 2000, pp. 77–80). This may have met his demand in a thinly populated country such as Iceland. To establish Latin schools in the former monastic houses may thus not have been necessary because of how small the Icelandic population was.

The plans of Christian III for schools for the former monasteries in Iceland appear in two letters, both dated 21 November 1542. In the letters, it is stated that Latin schools had already been established in decommissioned monasteries in Denmark and Norway. One of the two letters was addressed to Abbot Sigvarður in Þykkvabæjarklaustur, Prior Brandur in Skriðuklaustur, and Abbess Halldóra in Kirkjubæjarklaustur (DI XI n.d., pp. 176–78). The other letter was addressed to Abbot Halldór in Helgafellsklaustur and to the convent brothers in Viðeyjarklaustur (DI XI n.d., pp. 175–76). Abbot Alexíus had already left his monastery by then. Still, Abbot Alexíus had himself made an offer in 1541 to the bishop to take over the management of the monastery in Viðey again (DI X n.d., pp. 682–83). Nothing came of it, perhaps because the buildings were already demolished. In the same year, however, Abbot Alexius declared his loyalty to King Christian of Denmark by being one of those accepting, by signature, the Lutheran church ordinance in Alþingi (DI X n.d., p. 686). Moreover, the king withdrew his previous proposal to establish a school in Viðey in December 1542, instead declaring that there his officials should have their residency (DI XI n.d., pp. 179–80).

The king made a new attempt to establish a Latin school in Helgafellsklaustur in 1550, but that endeavor also failed (DI XI n.d., p. 750). Although the king’s aims did not come to fruition in Iceland, the letters from 1541 are a remarkable source of his intentions to build up the Icelandic society on a new basis after the Reformation. Yet, the same year as he sent out the letters about the schools, the king also required all those still residing in the former monasteries of Skálholt to be registered. The register is an important source for the number of monks and nuns still residing in the Skálholt diocese at the time of the Reformation (Table 2). The fate of other residents in these monasteries at this point, such as stewards, novices, lay people, or all those who accepted alms or medical care, is not known. Priests are occasionally mentioned as being a part of the female community in Kirkjubæjarklaustur, but these are not included in the king´s list from 1541, only the nuns and the abbess (Kristjánsdóttir 2023b, pp. 86–87). Nevertheless, one source mentions that in Viðeyjarklaustur there were 40 paupers in 1540, a year after the attack, but it has been suggested that they were originally housed there by the monastery (Ísleifsdóttir 2003, p. 116).

Table 2.

Residents in the former Icelandic monastic houses in 1542. It is worth noting that the name of one monk, Gunnlaugur, in Helgafellsklaustur, has been struck through. No abbot is registered in Viðeyjarklaustur in this year either.

The register from 1542 indicates, furthermore, that the ordained—brethren and sisters—did not leave their monasteries immediately during the Reformation in the Skálholt diocese in 1541, apart from Alexíus, the abbot of Viðeyjarklaustur, who was mentioned before, and possibly one brother, Gunnlaugur, in Helgafellsklaustur. His name was crossed out after the list was made (see Table 2). According to the newly accepted Lutheran church ordinance, ordained people were allowed to continue residing in their monasteries if they were old and in poor health, but under the condition that they would break their vows and adopt Lutheran customs (DI XI n.d., pp. 159–61, 247). Those abbots and monks who wished to leave had the right to receive clothes and travel money from the king (DI XI n.d., pp. 159–61).

In addition, the Danish king promised to support former abbesses and nuns in his domains while they remained in their monasteries (Danske Kancellis Registranter 1535–1550 1881–1882, p. 362). However, nuns and abbesses had very few options to choose between outside the walls of their monasteries. Monks and abbots, on the other hand, could serve as priests under the new Lutheran religion. They could also choose to marry. In fact, King Chrisitan III gave instructions in a letter 13 March 1545 on how the procedure for married priests was meant to be (DI XI n.d., pp. 379–80). (DI XI n.d., pp. 379–80; Jacobsen 1989, pp. 62–63). Ordained nuns could certainly marry, but seeing as it contradicted their vows, this was not as obvious an option as it was for men.

Despite the recommendation that nuns and monks break their vows, it is clear that some abbots and both the abbesses in the Skáholt bishopric continued to carry out their previous official duties to some extent after 1541 for a few years. There are, on the other hand, no sources showing that they received donations or that they purchased new farms, as they did while operating as monastic houses. Halldóra Sigvaldadóttir, who served as an abbess for 43 years in Kirkjubæjarklaustur, is addressed as such by Bishop Gissur in a letter in 1543. In the letter, Bishop Gissur asks her kindly not to host a woman who had fled physical beatings of her husband and sought refuge in the monastery (DI XI n.d., p. 271). The outcome of this case is not known, nor how long Halldóra and the six nuns stayed in the houses of Kirkjubæjarklaustur after this happened. Nevertheless, this was her last known official work, and it can therefore be said that the operation of Kirkjubæjarklaustur ended around 1543.

Abbot Sigvarður in Þykkvabæjarklaustur is one of those who continued to reside in his monastery after its closure, but not for long. In 1542, together with five other clerics, he requested that they would not, due to age and infirmity, be forced to follow other doctrine than the one they had followed for so long (DI XI n.d., pp. 138–39). Moreover, in 1545, Bishop Gissur sent a poor boy to abbot Sigvarður in Þykkvabæjarklaustur to study for priesthood—within the Lutheran teaching—under the abbot´s supervision. Kindness and respect seem therefore to have prevailed between the old abbot and the newly appointed bishop of the Lutheran custom, just as between the bishop and Abbess Halldóra. Interestingly, however, Bishop Jón Arason of Hólar, attempted—without success—to ordain Sigvarður as a bishop in Skálholt after Bishop Gissur´s death in 1548 (DI XII n.d., pp. 120–22).

Halldór Tyrfingsson, abbot of Helgafellsklaustur, appears likewise to have performed some duties after the Reformation came to the Skálholt bishopric in 1541. Bishop Gissur at least addresses him as an abbot in a letter dated 3 October 1544. The letter is also addressed to the convent brethren in his monastery, but the message concerned one of them, Gunnar, who had committed a crime. The bishop absolved Gunnar and re-ordained him as a monk in the monastery (DI XI n.d., p. 332). This indicates that there was a monastery operating in some form, and that even the Lutheran bishop had some kind of authority over the monastic brethren. Moreover, Gunnlaugur—the monk whose name was ruled out in the register from 1542—reappeared in a source from 1550. In it, it is claimed that he got on a ship and fled the country (Pálsson 1967, pp. 112–13).

Prior Brandur Hrafnsson in Skriðuklaustur appears to have stayed longest in his monastery compared to the priors of the other houses of the Skálholt diocese. However, he seems to have left it in 1552. The actual management of Skriðuklaustur ceased with the Reformation in Skálholt diocese. At least, there are no documents preserved indicating Brandur´s interference with official duties as a prior after 1541, but Bishop Gissur made him a priest of Lutheran customs the same year (Kristjánsdóttir 2012, pp. 46–47). It can be assumed that other residents, laymen, and patients stayed in the monastery at Skriðuklaustur after that, together with Brandur and possibly also the three brethren who were there in 1542. The Danish king did not officially take over Skriðuklaustur until 1554, when he installed Einar Árnason as the royal administrator of the landholdings of Skriðuklaustur and Kirkjubæjarklaustur (DI XII n.d., pp. 682–84). Einar Árnason, however, had clearly started to work as such before that time, because in 1552 he appeared in court in the case of a man that had disobeyed the new church ordinance (Steinsson 1965, p. 117). In any case, the year 1554 has generally been seen as the definitive end of Skriðuklaustur monastery, with some scholars arguing that it was earlier in 1541 following the climax of the Reformation in Iceland.

The Reformation of the Hólar bishopric is commonly bound to the execution of Bishop Jón Arason in Skálholt, in November 1550. However, the truth is that the last Catholic bishop of Skálholt, Ögmundur Pálsson, was also badly mistreated when he was replaced by the Lutheran bishop, Gissur. The agent of the Danish king, Christopher Hvítfeldt, was sent to Iceland in May 1541, along with 200 soldiers, to capture him in order bring him to court. Ögmundur had already agreed the year before to resign as bishop and had moved from Skálholt to Haukadalur in Biskupstungur. Still, he was captured while on a visit to his sister’s home near his own in Haukadalur. The king’s intention was to transport him to Copenhagen, but old Bishop Ögmundur died on the ship on 13 July 1541 (Ísleifsdóttir 2013, pp. 195–201). His death must have made it easy for the Danish king to reform the institutions in the Skálholt bishopric. At least, this event may have been highly important for the end of the Catholic monastic era in Iceland, even though it predates the execution of Jón Arason, Bishop of Hólar.

4. Reforming Monasticism in Hólar Bishopric

The dissolution of the monasteries in the diocese of Hólar followed a slightly different course because the bishop, Jón Arason, declined to accept the Lutheran ordinance when it was accepted at Alþingi in 1541. He refused both to leave his post and to dissolve the monastic institutions operating in his diocese. Thus, Þingeyraklaustur, Munkaþverárklaustur, Reynistaðarklaustur, and Möðruvallaklaustur continued functioning for the time being after 1541, although not entirely unaffected by the Reformation (Table 1). Moreover, as we will see, Bishop Jón tried whenever possible to resurrect some of the dissolved monasteries in the south.

The reasons he managed to delay the Reformation in Hólar for almost a decade may be found in the fact that the two bishops, Gissur in Skálholt and Jón in Hólar, made an agreement to leave each other in peace after the acceptance of the Lutheran ordinance, underlining that the Catholic church organization continued to be valid in the Hólar diocese (DI X n.d., pp. 643–44, 645). Nevertheless, both bishops obeyed the order of King Christian III of Denmark to transport valuables of gold and silver from the churches and monasteries of their districts so he could pay off his debts after the Count´s Feud (1534–1536), a war that brought about the Reformation in the kingdom of Denmark (Ísleifsdóttir 2013, pp. 92–93). As early as 1541, seneschal Christopher Hvítfeldt was given the task of collecting valuables from the Skálholt bishopric (DI X n.d., pp. 605–7). On 15 June 1541, Bishop Gissur sent Bishop Jón a letter confirming the transfer of ecclesiastical valuables, a total of 9 kg, to Denmark from his district in Skálholt (DI X n.d., pp. 644–45). It is not known exactly wherefrom the valuables were collected, but it is highly likely that the loot came partly from the monastic houses formerly run there.

The purpose of the letter that Bishop Gissur sent to Bishop Jón is not known, but it may have been meant to encourage Bishop Jón to do the same in his bishopric of Hólar. Another letter, dated 27 June 1541, shows Bishop Jón confirming that he was going to transport valuables to the king after all (DI X n.d., pp. 621–22). A little less than four years later, 13 March 1545, the Danish king, Christian III, reported formally that he had received over 6 kg of silver from Bishop Jón, sent to him from churches and monasteries in the Hólar bishopric (DI XI n.d., pp. 378–79). Unfortunately, in this case it is not specifically known from which monasteries the loot came. Yet, it is noteworthy that the very same day, 13 March 1545, the king appointed Sveinn Finnbogason as his steward of the landholdings of Þingeyraklaustur and Pétur Einarsson—the king’s official residing in Viðey—as the steward of the landholdings of Reynistaðarklaustur (DI XI n.d., pp. 377–78).

However, King Christian III was not only interested in transportable goods of silver and gold but also possession of the monastic landholdings that could provide him with profits. The landholdings were one of the main sources of income for the monastic houses, particularly though the coastal farms which provided access to the valuable resources of the sea. Thus, by the Reformation in 1541, the king obtained authorization over all farms owned by the Skálholt episcopal See, as well as those owned by the monasteries within the diocese. The king gradually took over all landholdings owned by ecclesiastical institutions in the country and established the king´s fishery (Icel. konungsútgerð) in 1544. The king´s fishery continued until 12 December 1769, when it was formally abolished (Aðalsteinsson 2022, pp. 28–29, 39–50).

Oddly enough, since the king had taken over the properties of both Þingeyraklaustur and Reynistaðarklaustur in 1545, it must have meant that their general operation as monasteries had been discontinued, just as the operation of Viðeyjarklaustur before. However, this was not entirely the case, because in a letter dated 10 February 1550, the abbot of Þingeyraklaustur, Helgi Höskuldsson, requests to be released from his duties due to his old age and infirmity. He says in the letter that he does this with the consent of his convent brethren and underlines that Bishop Jón had promised to put his son, Björn, in office as an abbot in his place (DI XI n.d., pp. 353–54). Thus, the bishop’s son, Björn Jónsson, thereby became the abbot of Þingeyraklaustur in early 1550, and, clearly, there were still some monks envisioned to take part in official duties as required by their order.

It is also highly uncertain if Pétur Einarsson fully took over the administration of Reynistaðarklaustur convent in 1545, as the official letter of the king indicates, because Sólveig Hrafnsdóttir is entitled as abbess in a deed in 1547 (Kristjánsdóttir 2023b). Still, it is easy to get the impression from the deed that she was addressed as an abbess only out of respect but that she was not serving as such anymore (DI XI n.d., pp. 545–46). It is in fact known from other female houses in Northern Europe that the female residents continued to be associated with their convents in one or another way without their former official capacities toward work (Jacobsen 1989, p. 56; Krongaard Kristiansen 2017, pp. 230–31; Lyons 2023, pp. 114–15; Lennon 2023, pp. 143–45). The royal takeover of the landholdings must nevertheless have involved a transfer of power over financial matters of the convent from the abbess of Reynistaðarklaustur to the new stewards, who allowed her to continue residing there.

In regard to Munkaþverárklaustur and Möðruvallaklaustur, both houses continued to operate in some form as former monasteries for a while after 1541, although the king had appointed Ormur Sturluson as the keeper of Munkaþverárklaustur´s landholdings on 14 November 1546 (DI XI n.d., pp. 505–6; DI XII n.d., pp. 214–15). Tómas Eiríksson kept his title as abbot until at least January 1551—a few months after the execution of Bishop Jón—as evidenced by his signature being found on financial accounts of the Grund Church that year as an abbot (DI XII n.d., p. 195). In March 1551, however, Abbot Tómas appears in a letter under the title “brethren” and seems to have lost his previous status (DI XII n.d., p. 207). Later that year, June 1551, the former abbot, brother Tómas, together with other noblemen in northern Iceland, swore an oath of allegiance to the king (DI XII n.d., pp. 263–70). After that, in 1551, 1552, and 1553, only Ormur Sturluson appears as the secular representative of the king in various matters of Munkaþverárklaustur (DI XII n.d., pp. 336, 344–45, 509).

At Möðruvallaklaustur, Bishop Jón set a steward at his episcopal See in Hólar, Björn Gíslason, in the office of prior over it in 1547. Prior Björn Gíslason replaced Prior Jón Finnbogason, who died in 1546 and had served as the prior of Möðruvallaklaustur since 1524, the very same year Jón Arason was ordained as the bishop of Hólar (J. Jónsson 1887, p. 263). Björn Gíslason appears later to have converted to Lutheranism, serving as a priest in Möðruvellir in 1553 (DI XII n.d., p. 553). The same year, 15 June, Björn married Hólmfríður Torfadóttir (DI XII n.d., p. 560). This was in accordance with the new church ordinance on members of the clergy being allowed to marry. Björn also signed the financial accounts of the Grund Church in January 1551, together with Abbot Tómas of Munkaþverárklaustur, where he is for the first time not entitled as prior Björn. He signed the oath of allegiance to the king in 1551 as well (DI XII n.d., pp. 263–70). Inevitably, in 1554, Björn Gíslason was officially appointed by the Danish king as the keeper of the 67 landholdings of Möðruvallaklaustur (DI XII n.d., pp. 553, 560, 681).

Although Bishop Jón had valuables from the churches and monasteries in his diocese transported to Denmark around 1545, he did not accept the Lutheran church ordinance. When Bishop Gissur died in 1548, their alliance ended. Bishop Jón soon thereafter attempted to take over the See at Skálholt and to restore the monasteries in the diocese, one by one. As we have seen, Bishop Jón tried to get the abbot of Helgafellsklaustur, Sigvarður, ordained as the bishop of Skálholt, but failed. The Lutheran supporters choose Marteinn Einarsson instead and he was ordained in 1549. Nonetheless, Bishop Jón continued his fight. In autumn 1549, when Bishop Marteinn Einarsson was on his first visitation of the Westfjords, Bishop Jón managed to take him as a prisoner. Bishop Jón was accompanied by his sons, Björn and Ari, in his endeavor, along with a group of Catholic supporters from all over the country. Subsequently, bishop Jón ordained his son, Björn, as the bishop of Skálholt according to the Catholic custom (Ísleifsdóttir 2013, pp. 219–60). Björn had previously been serving as the abbot of Þingeyraklaustur.

Early in the year 1550, Bishop Jón went with his two sons, Björn and Ari, to Viðey and reappointed Alexíus, the former abbot of Viðeyjarklaustur, to office as an abbot. It is worth reminding that Alexíus was one of those who signed the Lutheran church ordinance in Alþingi in 1541 (DI X n.d., pp. 632–33). A year later, Alexíus also formally promised, together with 27 other clergymen in the diocese of Skálholt, to follow it in their work (DI XI n.d., pp. 135–37). Obviously, Alexíus was never satisfied with the churchly reorganizing, no more than Bishop Jón, although it is unclear how much of role the former abbot had in reviving monasticism in Viðeyjarklaustur. From Viðey, Bishop Jón went with his entourage to Helgafellsklaustur and re-consecrated Abbot Narfi Ívarsson to the office of the former monastery, which was neither fish nor fowl anymore, rather than Viðeyjarklaustur, which had been desecrated in 1539. Narfi was the abbot of Helgafellsklaustur long before, from 1512 to 1527.

The mission of Bishop Jón Arason to resurrect Catholicism in Iceland was doomed to fail, not at least because Bishop Marteinn, Gissur’s successor on the bishop’s seat in Skálholt, had already decreed that all of Bishop Jón’s actions were no longer valid. Moreover, King Christian III had, in 1549, declared Bishop Jón exiled in a letter, dated February 11 of the same year, addressed to all Icelanders (DI XI n.d., pp. 691–93). The archbishop in Niðarós had even been stripped of his power as the financial and political representative of the church in Iceland and, consequently, the operational form of the church institutions located there changed. Inevitably, the last bishops in Iceland, as in other provinces of the Danish Crown, lost their positions as the leaders of the Catholic Church (Ekroll 2019; Cameron 2019). Obviously, Bishop Jón refused to give up his campaign, as may be observed from a letter, dated 8 March 1549, wherein he tried to obtain support from the Pope for his attempt to resurrect Catholicism in Iceland (DI XI n.d., pp. 695–98).

The world was altered. The government—both secular and sacred—of the country had moved from being divine to being earthly. Thus, the monasteries did not fit in at all with this social landscape altered by secular powers. In short, Bishop Jón and his two sons, Björn and Ari, were captured while seeking sanctuary in the church at Sauðafell in Dalir, but sanctuary had been abolished with the Lutheran Ordinance as all other Catholic habits. Their execution took place in Skálholt on 7 November 1550, and with Bishop Jón´s death all attempts to restore monasticism in the country were put to an end (Ísleifsdóttir 2013, pp. 252–60).

What work remained on behalf of the Reformists in Iceland, after Bishop Jón´s execution, was to empty the monastic buildings belonging to the bishopric of Hólar of valuables. The Danish king confirmed on 17 October 1551, that he had received various artifacts and silver from the monasteries of Hólar, Þingeyraklaustur, Munkaþverárklaustur, and Möðruvallaklaustur, but also from the bishop’s seat itself (Kancelliets brevbøger 1885–1886, pp. 83–84). In the confirmation letter, it is documented which artifacts were sent abroad but not what was from each place. Thus, the final looting of the monasteries in the Hólar bishopric in 1551 is seen as the final act of dissolution of the monastic houses, although they may have stopped functioning as such already when the first royal operators were set over their financial matters on 13 March 1545.

However, Reynistaðarklaustur is not mentioned in this list of emptied houses, perhaps because Abbess Sólveig Hrafnsdóttir may have stayed in her monastery until her death in 1563—as she was in fact allowed to do according to the Lutheran ordinance. There were also several nuns residing there as late as 1562, when Gunnar was mentioned as the keeper of Reynistaðarklaustur´s landholdings (F. Jónsson 1772, p. 112). This should not come as a surprise, as there are other examples from Denmark where some of the convents became Lutheran women’s communities after the Reformation under the direction of secular leaders (Jørgensen 2019). It is not certain if this was the case for Reynistaðarklaustur, but it should be kept in mind that Sólveig entered her convent in 1493. She was ordained abbess in 1508 and she died there in 1563. According to this, she spent nearly 60 years of her life in her convent (DI VII n.d., pp. 163–64; Kristjánsdóttir 2023b). There were hardly many other options outside it waiting for her.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy how many Catholic items have been preserved from churches and monasteries in the bishopric of Hólar, while most of the ecclesiastical items of the institutions in the Skálholt bishopric have vanished. Among the preserved items are altar tables from three of four monasteries in the bishopric of Hólar and ten embroidered altar cloths exclusively from churches in the Hólar diocese (Guðjónsson 2023; Kristjánsdóttir 2023a). It could be speculated that these Catholic items were preserved from the Hólar diocese because of work performed under Bishop Jón Arason´s resistance during the times of the Reformation.

5. Conclusions

The large number of charters, inventories, letters, and statutes preserved in the Icelandic medieval archive (Diplomatarium Islandicum, here DI) demonstrates how closely Iceland was linked to the archdiocese in Niðarós after its establishment at the height of its reign as the supreme head of Catholic Christendom (Kristjánsdóttir 2023a). The increased activity of the Roman Church in Northern Europe was also manifested by the founding of new archbishoprics and bishoprics from the eleventh century until the Lutheran Reformation in the mid sixteenth century. Iceland was a part of this development, as evidenced by these events and the writings of the people involved in them. The archbishops served as the pope’s agents within the geographically dispersed dioceses in Northern Atlantic societies and later often in liaison with secular authorities. As in other Roman Catholic Christian societies, archbishops supervised the local bishops in their districts, but with their help the policies and approaches of medieval Christendom were propagated to its northernmost provinces. Accordingly, the increase in the number of archbishoprics and bishoprics enhanced the power of the papacy but at the same time created new channels for the spread of the ideology on which the Roman Catholic Church was based. Monasticism was a part of this expansion, finding its way to Iceland through the establishing of monastic houses. At the same time, they played an important role in the overall history of Catholic Christendom in Europe.

Thanks to rich information preserved in written documents, the establishing of the monastic houses run in Iceland is quite well known, but—unfortunately—their dissolution in each case is not as clear because some of them appear to have been open some years after the Reformation in 1541. Earlier on, the running of several monasteries was discontinued after a short period of operation, while business at the remaining ones lasted for centuries, when monasticism had firmly settled in by the end of the thirteenth century in Iceland. The monastic settlements became the most controversial institutions because of the upheavals caused by the Reformation. By then, all of them were closed for good and their belongings were taken over by the Danish Crown. The royal takeover of the monasteries in Iceland appears to have been both disorganized and random, lasting from the time of the attack on Viðeyjarklaustur in 1539 until the commands of King Christian III had finally been fulfilled in 1554.

Gendered differences are also noticeable in the secularization and the dissolution of the monastic houses in Iceland. Although the female monasteries stopped functioning as such, the abbesses and nuns happen to have continued residing inside their walls under the protection of the royal power. On the other hand, the abbots of the male monasteries were generally replaced by secular representatives of the King. Moreover, unlike the abbesses and the nuns, the Icelandic abbots and the monks also used their opportunity to serve as Lutheran priests, and in some cases they did marry. No case is known of a women ordained in the Icelandic female monasteries who was married after the Reformation. Thus, the male monasteries went through an overall destruction as convents at the time of the Lutheran Reformation, but the female ones preserved their status until they gradually vanished with the women previously serving them.

As we have seen, the bishopric of Hólar remained Catholic longer than any other bishopric in Northern Europe, making the history of the Reformation different in this single bishopric. The reason is the resistance on behalf of Bishop Jón Arason against the Lutheran ordinance, a struggle that ended with his execution in late 1550. However, the monastic houses in the bishopric of Hólar eventually stopped functioning as proper monasteries long before their final closure after Bishop Jón Arason’s death. At least, King Christian III appointed secular keepers of their estates as early as 1545, and there is no evidence that they were serving around that time as monasteries. The other bishopric in Iceland, Skálholt, served as a Lutheran episcopal seat from 1541, and the monastic houses run under it were all dissolved around the same time.

Funding

This research was funded by the Icelandic Research Fund, grant number 228576-052.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found here https://bmn.hi.is/ and here https://steinunn.hi.is/is/rannsoknirresearch/kortlagning-klaustra-islandi.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aðalsteinsson, Haukur. 2022. Út á Brún og önnur mið. Útgerðarsaga Vatnsleysustrandarhrepps til 1930. Vogar: Minja-og sögufélag Vatnsleysustrandar and sveitarfélagið Vogar. [Google Scholar]

- Aston, Michael. 2001. The Expansion of the Monastic and Religious Orders in Europe from the Eleventh Century. In Monastic Archaeology. Edited by Graham Keevill, Mich Aston and Teresa Hall. Oxbow: Oxbow Books, pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Euan. 2019. Reforming Monasticism in Reformation History and Practice. In The Dissolution of Monasteries. Edited by Per Seesko, Loouise Nyholm Kallestrup and Lars Bisgaard. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, James. 2011. The Benedictines in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Danske Kancellis Registranter 1535–1550. 1881–1882. Copenhagen: Selskabet før Udgivelse af Kilder til dansk Historie.

- DI VII. n.d. Diplomatarium Islandicum 1903–1907. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- DI X. n.d. Diplomatarium Islandicum 1911–1921. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- DI XI. n.d. Diplomatarium Islandicum 1915–1925. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- DI XII. n.d. Diplomatarium Islandicum 1923–1932. Kaupmannahöfn: Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag. [Google Scholar]

- Ekroll, Øystein. 2019. Thrown to the Wolves? The Fate of Norwegian Monasteries after the Reformation. In The Dissolution of Monasteries. Edited by Per Seesko, Loouise Nyholm Kallestrup and Lars Bisgaard. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 166–67. [Google Scholar]

- Guðjónsson, Elsa. 2023. Með verkum handanna. Íslenskur refilssaumur fyrri alda. Reykjavík: National Museum of Iceland. [Google Scholar]

- Guttormsson, Loftur. 2000. Frá siðaskiptum til upplýsingar. In Kristni á Íslandi III. Reykjavík: Alþingi. [Google Scholar]

- Harðarson, Gunnar. 2016. Viktorsklaustrið í París og nærrænar miðaldir. In Íslensk klausturmenning á miðöldum. Edited by Haraldur Bernharðsson. Reykjavík: Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands and Háskólaútgáfan, pp. 119–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hugason, Hjalti. 2000. Frumkristni og upphaf kirkju. In Kristni á Íslandi I. Reykjavík: Alþingi. [Google Scholar]

- Imsen, Steinar. 2021. Nidarosnettverket. Collegium Medivale, 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ísleifsdóttir, Vilborg Auður. 2003. Öreigar og umrenningar: Um fátækraframfærslu á síðmiðöldum og hrun hennar. Saga 41: 91–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ísleifsdóttir, Vilborg Auður. 2013. Byltingin að ofan: Stjórnskipunarsaga 16. Aldar. Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélags. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Grethe. 1989. Nordic Women and the Reformation. In Women in Reformation and Counter-Reformation Europe. Edited by Sherrin Marshall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgig. 2021. A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia). Religions 12: 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensson, Gottskálk. 2016. Íslenskar klausturreglur og libertas ecclesie á ofanverðri 12. öld. In Íslensk klausturmenning á miðöldum. Edited by Haraldur Bernharðsson. Reykjavík: Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands and Háskólaútgáfan, pp. 9–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson, Finnur. 1772. Historia Ecclesiastica Islandiæ. Kaupmannahöfn: Gerhardus Giese Salicath. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson, Janus. 1887. Um klaustrin á Íslandi. Tímarit Hins íslenska bókmenntafélags, 174–265. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Kaare Rübner. 2019. New Wine in Old Bottles: Maribo Abbey after the Reformation. In The Dissolution of Monasteries. Edited by Per Seesko, Louise Nyholm Kallestrup and Lars Bisgaard. Óðinsvéum: University Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 243–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kancelliets brevbøger vedrørende Danmarks indre forhold 1551–1555. 1885–1886. Copenhagen: Kommission hos C.A. Reizel, pp. 83–84.

- KHLM. 1962. Kulturhistorisk Lexicon for Nordisk Middelalder. 1962. B. VII. Hovedstad–Judar. Reykjavík: Bókaverzlun Ísafoldar. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2012. Sagan af klaustrinu á Skriðu. Reykjavík: Sögufélag. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2017. Leitin að klaustrunum. Reykjavík: Sögufélag. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2021. Medieval Monasticism in Iceland and Norse Greenland. Religions 12: 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2023a. Monastic Iceland. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Steinunn. 2023b. The abbesses of Iceland. Religions 14: 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krongaard Kristiansen, Hans. 2017. Den Danske Klostre og Reformationen. In Reformationen, 1500-Talets Kulturrevolution. Edited by Ole Høiris and Per Ingesman. bind 2 Danmark. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Mårten. 2019. Continuity or Change. The Danish Franciscans and the Lutheran Reformation. In The Dissolution of Monasteries. Edited by Per Seesko, Loouise Nyholm Kallestrup and Lars Bisgaard. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, Colm. 2023. Sisters of the priory confraternity of Christ Church, Dublin, in the late Middle Ages. In Brides of Christ. Women and Monasticism in Medieval and Early Ireland. Edited by Martin Browne OSB, Tracy Collins, Bronagh McShane and Colmán Ó Clabaigh OSB. Dublin: Four Court Press, pp. 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Mary Ann. 2023. Keeping it in the family: Familial connections of abbesses and prioresses of convents in medieval Ireland. In Brides of Christ. Women and Monasticism in Medieval and Early Ireland. Edited by Martin Browne OSB, Tracy Collins, Bronagh McShane and Colmán Ó Clabaigh OSB. Dublin: Four Court Press, pp. 110–25. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Brian Patric. 1988. Daily Life in Danish Medieval Monasteries. In Quotidianum Septentrionale. Aspects of Daily Life in Medieval Denmark. Edited by Grethe Jacobsen and Jens Chr. V. Johansen. MAQ Newsletter 15. Krems: MEMO, pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, Tore. 1984. Johanniterna i Nordens äldsta tid. In Festsrkrift tilägnad Matts Dreijer. Mariehamn: Ålands Folkeminnesförbund, pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsson, Hermann. 1967. Helgafell: Saga höfuðbóls og klausturs. Reykjavík: Snæfellingaútgáfan. [Google Scholar]

- Steinsson, Heimir. 1965. Saga munklífis að Skriðu í Fljótsdal. Thesis in theology, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Sarah. 2014. From cathedral of the Isles to obscurity—The archaeology and history of Skeabost Island, Snizort. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 144: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winroth, Anders. 2012. The Conversion of Scandinavia. Vikings, Merchants, and Missionaries in the Remaking of Northern Europe. Yale: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).