Abstract

In contemporary development, feminism is divided into two major trends, that of difference and that of equality. The former tends to rely more on ontology and religious symbolism, and the latter on sociology and political praxis. This paper aims to show that this antagonism has as its background the complementarity and unity between both approaches, which are based on religious symbolism. Religious symbolism has both an ontological value and a sociological value, which give both internal consistency and external form to society.

1. The Primordial Mother in Mythology, Sociology, Philosophy, and Theology

From the historical and chronological point of view, the first figures that Homo sapiens venerated as creative divinities were the Great Mother Goddess or Mother Earth, who, in the late Neolithic period, adopted the forms of Gaia, Nut, Hecate, Pachamana, and who had other names according to the times and cultures. From the mathematical and philosophical iconographic point of view, they have also been represented in numerous figures and denominations. At this moment, it is not possible to differentiate between an ontological symbol and a sociological political symbol because the symbol has made all these meanings indiscernible.

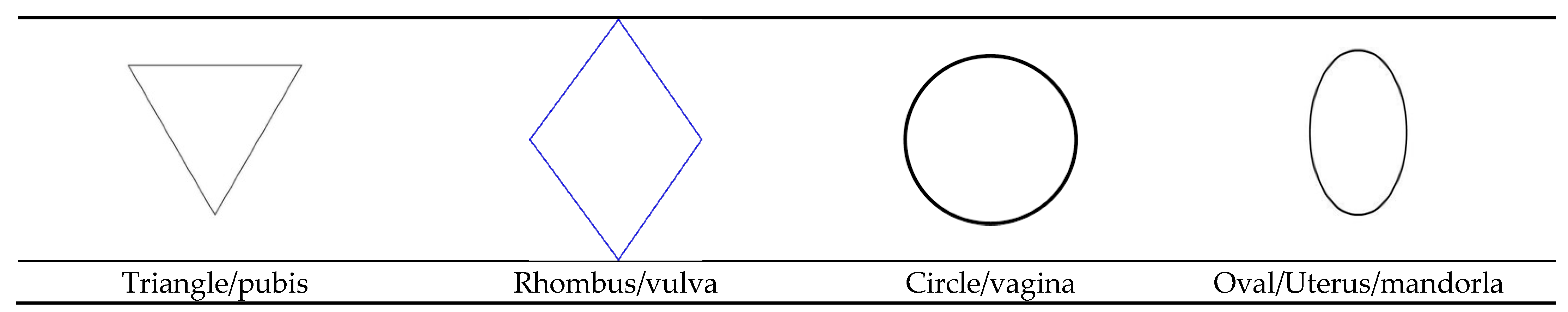

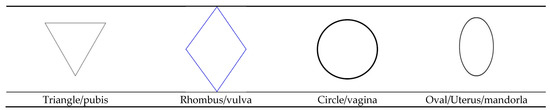

The first representations of the Mother Goddess are those of the female genitals as stylized geometric figures, i.e., the triangle, circle, oval, and rhombus, among others (see Figure 1), while the most classic, the shape of the fish bladder (vesica piscis), is later and permanently used by the Pythagoreans and the first Christians and is better known as the mandorla and pantocrator.

Figure 1.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regular_polygon, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollonius_of_Perga#Conics (accessed on 8 January 2025).

From the Middle Ages onwards, a slight differentiation between the religious and sociological and political meaning of the symbol can already be perceived, depending on whether it is found in the apses of churches or on war banners.

The process of generation and development of the cosmos from primordial matter is staged according to the modality of rituals, that is, from the point of view of body language and iconography, and it is described from the point of view of liturgical hymns and stories, and from the point of view of ordinary language.

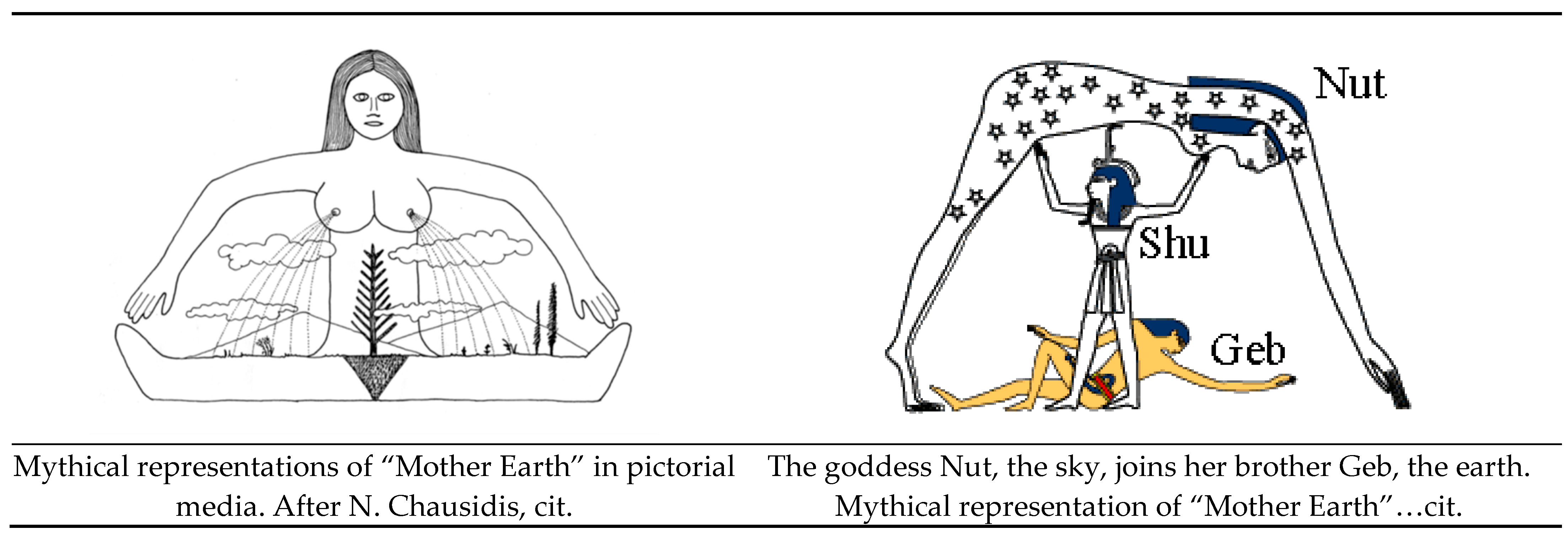

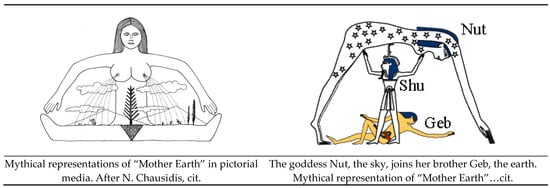

This equivalence is clearer in some representations than in others. For example, the equivalence between the Egyptian goddess Nut, the celestial vault, and her brother Geb, the earth’s soil, is very clear (see Figure 2)1.

Figure 2.

Representations of “Mother Earth” in pictorial media. After N. Chausidis, cit.

When abstract philosophical thought began at the beginning of the historical and urban era, the creation of the universe was described sociologically from rites of demarcation of a territory (for example, those described by Livy in Ad urbe condita), and philosophically from a mysterious, infinite, and ineffable First Principle, i.e., the One.

The ancient, historical–sociological and philosophical religious stories call this First Principle by different names from different perspectives, such as raw material, the soul of the world, number, demiurge, etc., and contemporary science does the same, calling it a quantum vacuum, Higgs field, or dark matter, although scientists assign them the same or very similar properties2.

The first philosopher to analyze and describe this process of the history of the universe, although based on Plato and Aristotle, in a complete and systematic way, as an exit (proodos, exitus) of this indeterminate matter from the First Principle, i.e., as its unfolding for the constitution of the universe and as the return of everything to it (epistrophé, reditus), was Plotinus.

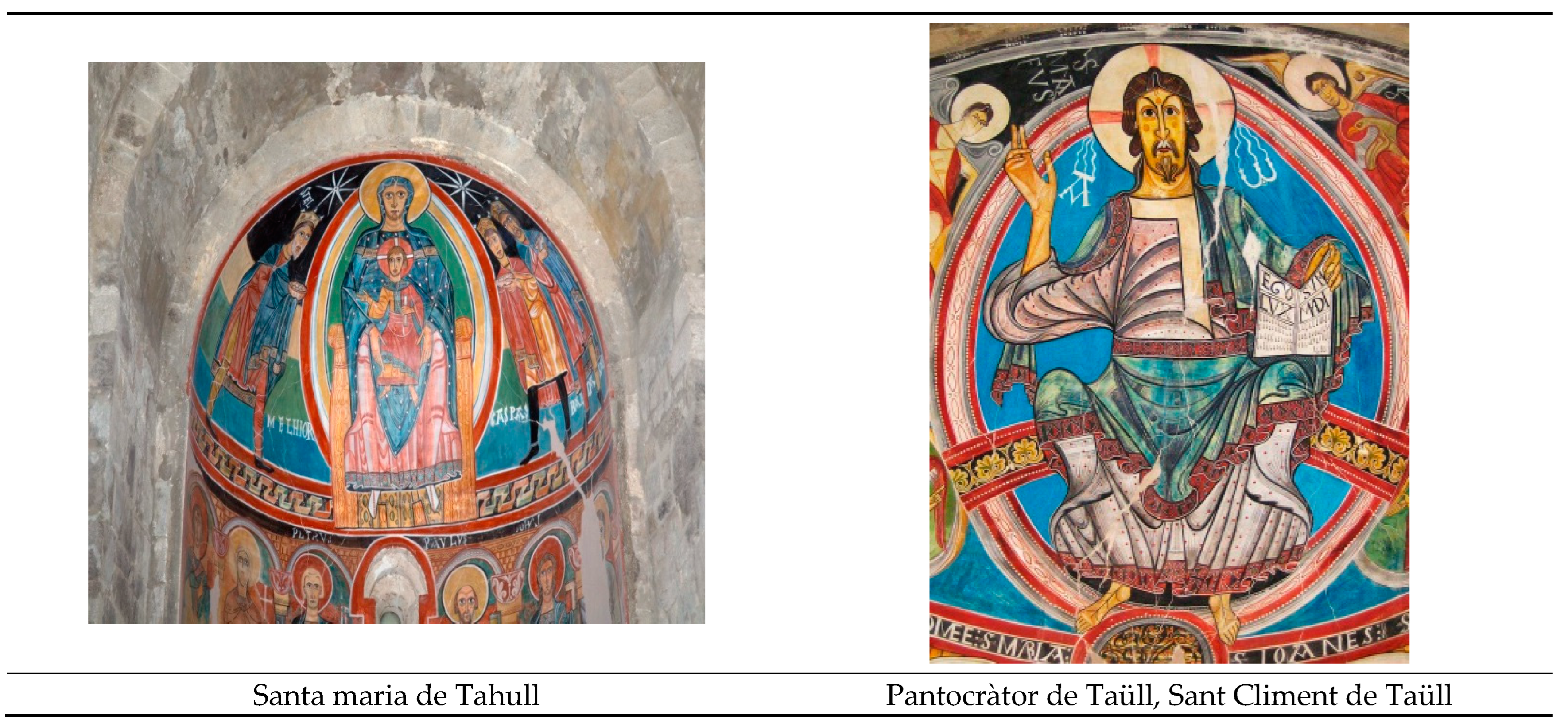

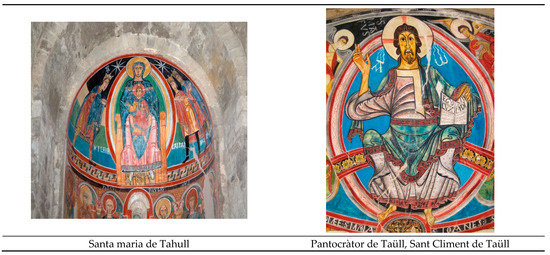

He calls the initial indeterminate matter infinite potency and interprets it as matter and as “mother”, i.e., as a philosophical version of the “mother goddess” of the rituals and mythologies of previous times3. From the point of view of sociology and politics, his mother appears in iconography not only as a throne of wisdom, but also as a throne of omnipotence, as a city center, and as a home focus, and her geometrical schemes provide the keys to the iconography of the feminine divinity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_Pantocrator (accessed on 5 Feburary 2025).

Since the twentieth century, with the appearance and development of quantum physics and existential phenomenology, it has become possible and inevitable to develop a cosmology from the point of view of matter, indeterminacy, proteic energy, or mother mass, that is, from the feminine point of view. However, at that time, the sociological feminine and the religious were already distanced and confronted. The feminine has begun to revalue itself and access political power as a sociological group and labor force, while it is devalued in the ontological and religious orders and begins to weaken as a group that sociologically realizes the values of pity and mercy.

The principle of indeterminacy begins to be accepted as constitutive of all reality, and conceptual tools are available to operate with the infinite and manage it, in philosophy, mathematics, and linguistics4, and that is why philosophy, mathematics and linguistics have demonstrated, in modern times, from the Renaissance to the 20th century, a certain gender bias, as various authors have pointed out5, in accordance with historical political and sociocultural configurations.

In ontological and religious perspectives, the universe arises from a duality or a triad. The duality is the Unlimited and the Limited, and the triad is the Unity of the Unlimited and the Limited. In the philosophical perspective, the unlimited is understood as matter and the limited as form; in the iconographic and mathematical perspectives, the unlimited is understood as a pair that is not closed on itself, open and indefinitely determinable, and the limited as a complete essence that is definitively determined.

In the sociological and political perspective, society also arises from duality: the master and the slave, the one and the many, and the powerful and the dispossessed, and the feminine belongs to the second sphere of these binomials. The terms used in iconography, mathematics, and philosophy to designate this duality are continuous/discrete and infinite/finite, and have a long historical development in the theory of perspective and geometric figures, number theory, and hylomorphic ontology.

The continuous and the indeterminate, such as the space–time field, or earth, water, air and fire, are understood as feminine because they produce or generate infinitely through division, i.e., they are infinitely divisible, with an inexhaustible fertility. The same happens in the societies described by Adam Smith and Keynes with wealth, and especially with money, the privileged icon of raw materials.

On the other hand, they are limitable in many ways, because they do not have limits or contours of their own, and, furthermore, once determined according to a specific form and limits, they can repeat that form indefinitely in an inexhaustible production, and also in very different productions. This is especially true for money, which Aristotle calls “artificial wealth” or chrematistics, because it can grow indefinitely, without ever reaching its fullness (Politics Book VII, 1323a.25–30).

The third form of the representation of divinity is the objective one, which results from a reflective monologue on it and its manifestations: science, philosophy, and, especially, theology.

The theological point of view has, in turn, three levels: the liturgical one, which belongs to body language; the narrative, which belongs to ordinary language; and the theological interpretation, which belongs to the objectifying reflective monologue. The unity of the three is what gives greater consistency to knowledge and communication with the divine.

The objective theological point of view formally appears when the stories about the origin of a people and their own culture, contained in the epic memory of the first social groups, are considered and taught as communicated by God to men; that is, it is consolidated when the figure of the transmitter formally also becomes an interpreter, i.e., a prophet and priest, and the story is taken as a revelation.

This occurs in all peoples and all cultures during the periods in which ordinary language is formed (beginning of the Chalcolithic, around 5000 BC), and is often also considered revealed, i.e., taught by divinity, because it this is as beneficial for survival as hunting and reproduction.

It is at this point that the epic stories are consolidated, where the social group becomes aware of its own history and its progenitors, 108 when the ontological and theological reflection on the figures of the mother goddess and the First Principle begins, and they begin 109 to be configured conceptually, differentiating themselves from the imaginative epic story.

2. Innocence, Freedom and Evil

The Judeo-Christian Bible begins the account of creation with the following description of a state of original innocence and the irruption of evil:

“And they were both naked, Adam and his wife, and they were not ashamed”(Gen 2.25)

[…].

10 “I heard your steps in the garden”, he replied, “and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid myself”.-

11 He said to her, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree that I told you not to eat?”

12 The man replied, “The woman you put at my side gave me some fruit, and I ate it”.

13 The Lord God said to the woman, “How could you do such a thing?” The woman replied, “The serpent seduced me, and I ate it”.(Gen 3. 10–13)

The first stage of world history is the position of matter outside the One and women as the center of the social order. That which is placed outside is wisdom (Sophia, Hochma), what Proclus calls the maternal, which is infinite power and also infinite nourishment, i.e., energy, which takes on many modalities.

This intellectual version of history has another imaginative prehistoric version, with four types of divinities, namely, cosmomorphic divinities, such as stars, phytomorphic divinities, such as plants, zoomorphic divinities, such as animals, and anthropomorphic divinities, such as human beings.

These four types of divinities are usually divided into two classes, male and female, but these two classes are unified into one, which operates as a kind of bridge between the imaginative plural divinities and the divinity conceived intellectually as a unit, which is the figure of the androgyne.

In the cited text of Genesis, initially the human being was not a separate duality, but a single human being or a dual unity, who did not feel ashamed of his nakedness, because one does not feel shame when one is alone or one is one, i.e., with a spouse. However, when the unity is broken, the duality appears, and with it the estrangement that makes shame possible.

“I was afraid because I was naked. That is why I hid myself.

—He replied: And who told you that you were naked?”(Gen 3, 10)

It is Mephistopheles who breaks the innocence and unity of the androgyne who is naked and shows that he is not one but two; as such, the serpent, the most cunning of animals, who, moreover, is in some way a collaborator of God in the task of creating the universe. The names of Mephistopheles and androgyne do not appear in Genesis but were the symbols of the appearance of evil in the cosmos and in society before the differentiation between the ontological and the sociological order.

According to Eliade, Mephistopheles is not the enemy of God, but of life, of stillness, and of starvation. He is the enemy of women (“I will put enmity between you and woman, between your offspring and hers”. Gen. 3. 15)6.

In the folklore of popular religion, God and Mephistopheles even have a certain sympathy for each other, as also occurs in the Book of Job, and a good reason for this is that God (Indra) and the Dragon (Vrtra) are brothers: the father of both is Tvastr7.

The second moment of cosmologies is usually the breaking of peace and original innocence, i.e., the unleashing of a struggle between darkness and light, between good and evil, between provocation and choice, in what the Greeks call the Titanomachy, or the war between the gods of the first generation (the Titans) and those of the second.

In Hindu cosmogony, the universe also unfolds from a primordial rupture as described by the Greek poets, but this time recorded in the corresponding sacred books by Hindu theologians8.

The figures of Mephistopheles and the androgyne are the staging of the appearance of evil and freedom in the visible sociological order, which is transposed to the invisible theological order.

They mark the beginning of the differentiation between the mythological imagination and the philosophical theological conceptual intellect, because they can unify at one point the coincidentia oppositorum (coincidence of opposites) on the logical and ontological level, the inorganic and organic level, the pre-social and social level, the pre-political and political level, and the premoral and the moral and immoral level. On many others levels, it is linked to the unfolding of the social, philosophical, and religious history of the West.

When Plato recounts the myth of the androgyne at the banquet, he describes the development of Western history as a problem and conflict between the one and the multiple. In the ontological order, this viewpoint is expounded in the Parmenides, in the cosmological order, it is expounded in the Timaeus, in the psychological order, it is expounded in the Phaedo, in the ethical order, it is expounded in the Phaedrus, in the political order, it is expounded in The Republic, and in the sociological order, it is expounded in The Laws. This viewpoint always comes from a primordial matter and soul of the world, which can unfold and collect all the manifold about itself in a unity.

If we take into account that since Anaxagoras and Pythagoras, a good part of Pythagoreanism and Neoplatonism explain the cosmos and society starting from an original matter, or a primordial mother, we can see in this myth the argument of the history of the cosmos and society, i.e., of the exitus reditus systematized by Plotinus.

In the beginning is the mother, who is a dual unity, like the hermaphrodite Innana and many other male and female divinities, who, as Eliade points out, constitute an original unity and generate by parthenogenesis. Due to an initial shock, the dual unity is divided, and the children are torn from the mother’s body.

There is no account of the reason for the externalization of the indeterminate as a unit outside the One in all accounts of the split, i.e., of why it is first the unlimited and then the limited, of why each one wanders around lost, desperately searching until death for the other half of themselves, guided by the madness of desire (eros), of why the struggle for unity between the two sides continues, or of why duality continues from the beginning of prehistory to the present, up to the formulation of the principle of complementarity by Bohr at the beginning of quantum physics.

But he does realize why, in a large majority of the stories, the origin of discord and of great divisions and wars is women, or the beauty of women

Throughout prehistory and history, and from the development of modern and contemporary science, there has been a certainty that woman, i.e., the woman’s body, is energy. However, she realizes why, in a large majority of the stories, the origin of discord, great divisions, and wars is women. Likewise, it remains a constant that all the elements of the body, after death, return to dust, to become food and energy again, and the key role of women in the funeral rites of the accompaniment of the deceased to the afterlife remains constant. It is also a constant that all the elements of the body, after death, return to dust, to become food and energy again.

This circularity, which is often called regressus ad uterum, and which is one of the versions through which the redemption of the human species is described, appears in various interpretations of cultures, various schools of psychoanalysis, and various mythologies, and is one of the ways in which the symbol and human consciousness are used as a hinge between the visible sociological world and the invisible religious world.

This articulation between the sociological–cosmological and the ontological–religious extends to a large number of cosmic elements, especially food.

In addition to the food proper to the gods, i.e., nectar and ambrosia, the immortals give other salvific foods to mortals, and often even convert themselves into foods with specific healing and salvific qualities, offering them forever as gifts to men, and, thus, leading them to fulfill the desires of their love; namely, to be food for loved ones, men, children, etc.

Thus, Persephone transforms the mortal Menta into the mint plant; from the blood of Crocus, saffron is born; there is also the almond tree of Agditis, the pomegranate tree of Dionysus, the apple tree of Melos, and so on with many others. In prehistory, they do so in reality, and in history in ritual. The Hellenistic imagination draws in splendid figures what the Greek intellect later embodies in solid concepts, and later Christianity also expresses the same gift on both levels simultaneously with radiant metaphors.

The symbol is the piece that articulates the religious sociological world with the ontological cosmological world, the human with the divine, and the key to this articulation is, in turn, the woman.

3. The First Creature, Self-Consciousness of Nothingness, and Wisdom

The exit from the maternal womb is a tearing apart of unity and a fall into corruption because life is movement, time, separation, and corruption, but it is also purification, and that life, already purified, is a return to the maternal womb, to the intermediate world, according to the different schools and rituals of the mysteries, not without complicity between God and Mephistopheles.

This circuit of exit and return is expressed sociologically at the different levels of being (physical, biological, psychological, existential, religious, ontological, and theological) and they have their own realization and description in each one of them. In some versions of Neoplatonism and Christianity, it is said that they are sensible signs that cause what they mean, that is, sacraments, and that they are the taxa of the social and legal order, i.e., the factors that determine social identity, whether one is a man or a woman, a child or an adult, single or married, innocent or guilty, etc.

This is recorded at a first preconscious biophysical level as a set of hormonal secretions and reflexes which carry their own ritos9. It is also experienced at a second psychological and existential religious level in maternal intimacy as a feeling of being in oneself for the other, as a primordial form of being for oneself as a unity of two, as a dual being, and also with their corresponding rites10, and it is manifested at a third ontological intellectual level by becoming transparent for oneself as a dual unity in relation to God.

The first two moments begin with a type of maternal–corporal knowledge that is at the same time action and that spontaneously produces gestures and movements of veneration on the part of the mother, such as the kiss, the caress, breastfeeding, the overflow of joy and tenderness in trembling and discomfort, and, finally, everything that can be and is the beginning of the rites that constitute the liturgy of welcoming the new being into existence, the first of all the rites of passage11.

Rites of passage are the taxa of sociological and legal identity, which in some extreme forms of equality feminism are considered words lacking real content (nominalism), while in the feminism of difference they are taken as the real ontological content of rites, that is, of the social structure and the legal order.

From the moment of departure, man begins the fall in its various forms, and always has rites and sacraments of one kind or another, whether they are the Orphic, Dionysian, Eleusinian, Hermetic mysteries, etc.12

From the moment of his departure, man begins his fall in its various forms, and he always has resources of one kind or another, whether they are the Orphic, Dionysian, Eleusinian, Hermetic mysteries, etc.

Fallen man knows that he can always turn to woman and especially to his mother, because she is always there, no matter how low man has fallen and how deep hell is. This is so because the relationship of the primordial Mother and Universal Mother (MU, as Ibn Gabirol calls her) with the One is one of continuity13, and that of the primordial mother with men as well14. The Word is always in the beginning, that is to say in matter-wisdom, and the existence of all creatures is in those maternal entrails15, which are also their beginning.

That is why, from a sociological point of view, certain purification rites are performed by women, such as the priestesses of Asclepius, the Eumenides, the Vestals, and others.

That is why man can go down to hell, and return from there.

That is why man cannot stop going down to hell, nor stop returning from there: Gilgamesh, Ulysses, Christ, Aeneas, Dante, Don Juan, Milton, Faust, Baudelaire, Dostoevsky, and some others go down and return. Purification is a battle between man and the Archangel Michael, aided by the woman, Anticlea, Beatrice, Agnes, Margaret, and Sonia, who are Ariadne’s thread, the umbilical cord with which, through them, he remains connected to the heart of the One.

That is precisely the answer to Nicodemus’ question about salvation: “How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter his mother’s womb and be born again?” (John 3:4–6). In fact, he returns to the dust, to the earth, to the bosom of Mother Nature, to the intermediate world, to the stage where “women received their dead by resurrection” (Hebrews 11:35). The womb of the cosmos is the maternal womb, to which the living return when they die to be born again.

Return means returning to the starting point, and, therefore, implies innocence and purification, i.e., becoming like children. It implies returning to the beginning of creation, which here is called beginning, and which involves passing through the various sufferings of life, through the various forms of destruction and of nonexistence.

There are numerous conceptions of exitus reditus, and it is common to distinguish between two large classes. In the first class, exitus is conceived by all religions in general as the beginning of the cosmos and of man, and reditus is conceived as a return to that same paradisiacal cosmos where animals and men live in happy harmony for all eternity.

This reditus has its sociological expression in the funerary rites of purification, which vary widely from one religion to another.

In the second class, exitus is a transitory stage of the cosmos and not a permanent state of it, and reditus is also a transitory stage, a provisional return that culminates in a second and definitive reditus, in which the cosmos and humanity are integrated into the intimate relationship of the One and its hypostases. This culmination of the reditus consists of the eschatological mystical union with the One and also comprises various rites and sociological phenomena in the various religions.

This second class of reditus is systematized by Plotinus and is conceived not only as a return to the innocence of paradise, or to the constitution of “a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth have passed away (Rev. 21.1)”, as expressed in Christian terminology, but also as participation in the bosom of the three hypostases of the One.

Christianity inserts between the first and second return the “elevation to the supernatural order” that generates a dense theological complexity16. In fact, this second return, which consists of the participation of the human person in the intimate life of the One, or, in Christian terms, in the dynamics of the Trinitarian processions, is subsequently elaborated by all of philosophy and historical theology, Christian, Islamic, Hebrew, Buddhist, etc., generating treatises of a motley complexity. Consequently, it generates treatises of a variegated complexity in the ontological order17, and, on the other hand, creates a whole panoply of rites that constitute in the sociological order half of the ceremonies that make up the “liturgical year” in the various confessions.

This second return, of which there are numerous versions, usually implies and integrates the first, i.e., the recovery of the paradisiacal original innocence, to then reach, also through the woman, the transformation that allows one to pass from this first return to the second, of a higher order, which here is characterized as participation in the intimate life of the One, and is called the Beginning.

The sociological correlate of these two theological moments is, in the first place, the unification of all men in the Roman Empire and in the Church, which is due to the unification of humanity in the empire of Alexander, to the granting of Roman citizenship to all the inhabitants of the empire by Caracalla in 212, and to the declaration of Christianity as the official religion of the Empire by Theodosius in the year 380.

Secondly, the sociological correlate of the second return is the glorification carried out by the church of the heroes and protagonists of salvation. In a certain way, there is a correspondence between the centrality that Plotinus and Dionysius give to the One in the ontological order, and the centrality that Theodosius grants to the Church in the sociological order.

46 Mary then said: “My soul sings the greatness of the Lord,

47 and my spirit trembles with joy in God, my savior,

48 because he looked kindly on the smallness of your servant.

48. ὅτι ἐπέβλεψεν ἐπὶ τὴν ταπείνωσιν τῆς δούλης αὐτοῦ.

48 quia respexit humilitatem ancillae suae From now on all generations will call me happy, 49 because the Almighty has done great things for me: his Name is holy!(Luc. 1.)

“Because he looked with kindness on the humility of his slave”, because he noticed the surrender of his creature18. What was the smallness or humility of the servant, the slave? And what was it to look at her with kindness or to pay attention to her?

The first ontological answer to these two questions is probably, as has been said, that of Plotinus. The smallness or humility of the servant consists of her being nothing, not in her not existing from the empirical point of view, but in her being nothing from the ontological point of view, that is, she is not in herself. She is not in her ontological self prior to creation or in her empirical self at the moment of the Annunciation.

In her ontological self prior to creation and then at the very moment of creation, she is apeyrodýnamon, or she is proté apeiria. For this very reason, “the Almighty has done great things in me” (ὅτι ἐποίησέν μοι μεγάλα ὁ δυνατός, quia fecit mihi magna, qui potens est).

What great things can the Almighty (ὁ δυνατός, qui potens est) do in this creature who is nothing and wholly at his disposal? And what consciousness can it have of itself and of great things? The consciousness it can have of itself, if it is a true self-consciousness, is that in itself it is nothing, since it is not in itself, or since its subsistence is borrowed and contingent19. In that case, the self-consciousness of the primordial creature is the self-consciousness of nothingness.

And what are the great things that the Almighty makes out of nothing? Well, the whole creation, the universe, humanity, i.e., what is recounted in the first verses of Genesis, which she probably knew.

In the sociological order, the great things accomplished by the Almighty are, for the Jews, the building of the kingdom of David; for the Romans, they are the building of the empire; and for the Christians, they are the building of Christianity. Christianity, on the other hand, is the symbol that links the first principle, God or the One, with human society, articulated according to the various forms of recognition of this link

The Pythagorean school of Plato and Plotinus said that the first thing that the One puts outside of itself is the Indeterminate, the infinite power, and that it puts it outside of itself because it has had it in itself before, from the beginning. What it puts outside of itself in the second place is the Determined, the number, the Logos, as we have also seen. In the One, one can differentiate the Unlimited from the Limited, and what the One puts outside of itself is another one made up of both things, beginning with the Indeterminate.

The Indeterminate of the One puts itself outside in a generation of mediate continuity, like an eros of infinite power, like the feminine or the maternal, that is, like the mother, who from the religious theological point of view is Wisdom. The Determining, “which was in her from the beginning” (Io. I, 2) is put out in the second place, in a generation of immediate discontinuity as the only masculine determinant, which from the philosophical and theological point of view is the Logos.

That is to say, nothingness is the beginning from which emerges, on the one hand, the universe, from which, and through Mary, God becomes man, and on the other hand the same universe from which, and through Eve, Abraham and the Abrahamite confessions historically emerge, which exercise their prominence in the development of Western culture.

All these perspectives are unified in some ontological–existential analyses of the personal self and of God.

As Nishida points out, God cannot contain nothingness and evil as something opposed to him, distinct from him and threatening. He must have it integrated into himself in order to be the One, the Almighty God.

“The absolute God must include absolute negation within himself and must be the God who descends to the very depths of evil […]”

God is the absolute precisely in the structure of a dynamic equilibrium of “is” and “is not”. And the human self, the image of God himself, is similarly a contradictory identity of good and evil. Thus, Dimitri Karamazov discusses the beautiful lies hidden within Sodom and that the beautiful is both terrible and mystical. There is a war between God and Satan and the battlefield is the human heart.

Our hearts are essentially that battlefield between God and Satan. Yet the reality of the self as a volitional person lies there. The self is always rational as a self-determining predicate. At the same time, it exists as an objective reality that negates the predicate. Thus, it has its existence in the midst of radical evil, in radical contradiction with itself. From the moral point of view, Kant refers to this as the innate propensity to evil. In my essay “Life”, I used the word “disposition” in the same sense. We have this disposition towards evil as a result of the unfathomable contradiction of our existence”20.

The self-consciousness of nothingness cannot in any case be conscious of having hindered God’s creative action, that is, it cannot be conscious of impurity, of sin, or of destructive action. It can only, as a creature, be conscious of the possibility of affirming itself while affirming God (worship) or without him (sin), that is, conscious of the possibility of evil, conscious of freedom, of one’s own freedom and that of spiritual creatures, and conscious of that battlefield which is familiar to Socrates, to Dostoevsky, and to all men and all women21.

On the other hand, it could also have some kind of consciousness of the hostility towards it of the forces of sin, some kind of consciousness of the announcement: “I will put enmity between you and the Woman, between her offspring and yours. She will tread on your head, and you will strike at her heel” (Genesis 3:15). And she could be aware of this because she knows not only from the point of view of the material and efficient cause, but also from the point of view of the formal cause and the final cause.

It is in this scenario of intimate self-awareness where the self-awareness of nothingness, Mary, is found by Socrates, Dostoyevsky, and all the women of human history, although in these cases there is self-awareness of impurity, sin, and destruction, and also true self-awareness. The self-awareness of one’s own nothingness in any creature is an encounter with wisdom, i.e., an encounter with Mary. It occurs when men become socially, legally, and politically aware of their dignity and play a leading role in it, and women of theirs, and prepare for their own protagonism, reformulating the relationship between the sexes.

When centuries after the empirical appearance of Mary, human society becomes aware of the closeness of opposites, of the divine ontological One and the empirical individual of human society, and of the similarity between the divine One and the human individual. It is then perceived that the hierarchical principle of the organization “God, country, king” can be replaced by the principle of “liberty, equality, fraternity”. At this point the emergence of feminism takes place, and with it the emergence of self-awareness of the dignity of women in the cosmos and in history.

4. The Intermediate World and the Impurity of Women

In the case of the Greek religion, as well as in the Hebrew and Christian religions, the fall has as its antecedent an episode of struggle between the gods, which explains in some way why evil appears in the human world. It appears because it has previously appeared in the intermediate world.

This intermediate world is external to the divine intimacy and prior to the constitution of the existing universe. That is why it is intermediate. It is intermediate between the beginning of the cosmos and of the living as the stage of the demiurge and the soul of the world, and their effective appearance in the formed cosmos and the offspring born by the females. It is intermediate between the death of humans and the universe, on the one hand, and the parousia or access of men and the cosmos to divine intimacy on the other.

Since the remote Paleolithic, Homo sapiens has had the custom of considering women impure after the menstrual flow, with consequent purification ceremonies.

Bloodshed, whether accidental or deliberate, is always an extraordinary event, one that provokes alarm or awe-filled anguish and fearful respect. Blood, and especially the shedding of blood, is something tremendous and fascinating because it has something of a sacred mystery22. This occurs both in the most distant prehistory and in the most urbanized cultures of the 21st century, even though the phenomenon is contextualized by sirens from ambulances, police, and firemen, by traffic jams, and by images on various types of screens and messages from various types of microphones.

In ancient times, there were two types of bloodshed: that voluntarily provoked in hunting and initiation rites, in transfusions, oaths and pacts of various kinds, which are usually public and with the participation of several people, and that unprovoked or fortuitous, either due to knowable causes, for example, the attack of a wild beast or a fall from a cliff, or due to unknown causes. The latter are usually private and without the intervention of third parties. Among them is the menstrual flow of the woman, an event that she experiences alone, with fear and trembling, and which generally leads to a certain type of exclusion from the community for some time.

There are at least two classic studies on the impurity and purification of women from menstrual flow. One is Sir James Frazer’s work, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, first edition 1890, with a second edition in twelve volumes 1907–191523, and another is Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s research, Le surnaturel et la nature dans la mentalité primitive, from 193124.

Impurity is contagious and dangerous and can cause various kinds of evils to the people, things, places, and times that are contaminated by the impure woman. For this reason, she has to be isolated from the community and taken to a special hut, built in a remote place. She cannot touch the ground of the village with her feet, nor look at the sky; she cannot touch relatives, animals, plants, or tools of work, war, or domestic use, because it would make them impure, sick, useless, or even cause death. This action and effect of weakening, deforming, or annihilating is called “witchcraft” or “sorcery”, and it is produced by the impure woman independently of her intention and will25.

“Can we try to go further, and investigate why catamenial blood constitutes such an “impurity”, such a “poison”, for the woman herself and for those around her, capable of stopping the growth of plants, of causing illness and death, etc., in short acting as a real spell?”26

“So what makes this blood so dangerous? […] comparing beliefs and practices related to catamenial blood with those related to other blood losses in women will help us understand its origin”27.

“Mr. Elsdon Best finally gives us the key to this enigma. “Catamenial blood is a kind of human embryo, an immature or undeveloped human being: hence the tapu. “The paheka (catamenial blood) of a woman is a kind of human being, it is a person in an embryonic state”. Another of my informants, an old man, told me: “This blood is a kind of human being, because if the menstruation stops, then it becomes a person; that is, when the catamenial blood ceases to flow, it assumes human form and develops into a man”. Mr. Elsdon Best adds: “There are several instances in native legends of menstrual blood turning into a human being… or sometimes into an evil spirit”””.

This text is decisive. It throws a vivid light on the fear which the periodic indisposition of women caused the ancient Maoris. What so frightened them was not only the loss of blood itself, but the appearance of an embryo which did not reach maturity, and which was, therefore, a “spirit”, that is, a particularly frightful death. For menstrual blood, while it is the red liquid which we perceive, also has a wairua (cf. Primitive Soul, chap. IV, p. 176) which can do much harm.

In other words, menstrual blood, before it leaves the woman’s body, is an embryo of a human being, living, and which, if it were not expelled, would take human form. Once it leaves the body, this possibility is destroyed. What terrifies the Maori is that it continues to live, but in the manner of the dead, that is, in the state of a spirit. These spirits are particularly evil and feared, as are those of fetuses expelled in abortions and miscarriages, and those of children who are stillborn or die at an early age.

Elsdon Best puts it in the following words: “A fetus expelled prematurely is always a danger to society, because its wairua may become an atua kahu (kahu means the enveloping membrane), a cacodemon, an evil demon, who delights in tormenting men. … Such a spirit may take up residence in an animal (dog, lizard, or bird) and cause incalculable harm”28.

Menstrual blood is the sacred creative power, which has been hindered in its path towards the formation of a normal living being, an opposition to the creator, which occurred in that mediation between the creator and the creature that is the female, the woman, the mother. Menstrual blood is one of the greatest possible sins.

Woman is the intermediate world, the mediator where indeterminate matter, the processes of embryological development, is a mediator, because it is in her that indeterminate matter, the processes of embryological development, becomes matter determined by quantity, that is, nature or essence. In her resides the power, whether or not it is consciously controlled, to generate a normal child or a monster, and this power over nature is called witchcraft, sorcery, or magic29.

In the Jewish culture of the first century, there is memory of these and other rites, whether their own or those of other foreign peoples, and worship is no longer lived only in the first three senses of prayer that Origen points out, i.e., as action, as obedience to the law, and as a proclamation or declaration of faith in what has been promised, but also in the fourth sense, i.e., as repentance, heartache, and mercy.

The New Testament declares, “Go therefore and learn what this means: I desire mercy, and not sacrifice. For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners, to repentance” (Matthew 9:13), and he does not declare it as a novelty, but as an update of an already ancient tradition, collected in various places in Scripture, such as Psalm 51.

When it is said that “Meanwhile Mary kept these things and pondered them in her heart” (Luke 2:19), she welcomed into herself the impurities and purifications of the women who had preceded her and those who would come after her, and the rite of purification was being lived with ecclesial solidarity, and with a contrite heart.

In Greek cosmogony, the intermediate world is the time and place of the activity of the demiurge and the soul of the world, which generate order, and, at the same time, it is the time and place of the struggle between the first pair of gods, Uranus and Gaia, and the second and their generation, Cronus and Rhea with their brothers, the Titans. This combat is called Titanomachy, and from it comes the set of Olympic gods governed by the authority of Zeus, father of gods and men30.

The Titans kill Dionysus, son of Zeus and Semele, dismember him and devour him. As punishment, Zeus strikes them down with his lightning bolt and from the ashes human beings are born, who already carry within themselves an original evil, a primordial sin, that of the Titans, from which they must purify themselves throughout their lives in order to return to the immortals.

In the Hebrew tradition, evil comes from Satan, the enemy of God, who fights against him and seeks to make his children abandon him and rebel against him, as is shown above all in the Book of Job31.

In Christianity, Satan, the enemy of God, is also the one who causes the fall of Eve and Adam, transformed into a serpent (Genesis, 3, 1–13).

In the Greek, Hebrew, and Christian worldviews, evil does not originate in the human world or the historical world, but in the intermediate world, and it does indeed arise in a Titanomachy, where evil results from the action of demons.

Titanomachy is well documented in Greek mythology and the Hebrew scriptures. It is also recorded in the Christian Old Testament, and in the New Testament, especially in the Apocalypse and the letters of Paul, although it is only mentioned in the Synoptics: “And he said to them: I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. Behold, I give you authority to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy” (Luke 10:18–20).

The Titanomachy does not frustrate the project of creation;t on the contrary, it opens the project of salvation, that is, it opens the plan of the incarnation of the Word and the integration of all creation in the intimacy of the Trinity, for which reason the sin of the Titanomachy and that of men receives the name of Felix culpa. In the proclamation of the Mass of the Easter Vigil the following is proclaimed: O felix culpa quae talem et tantum meruit habere redemptorem, “O happy fault that won for us so great and so glorious a Redeemer” (Matthew 11:18)”32.

From the sociological historical point of view, Titanomachy is the symbolic projection, in the religious ontological order, of the conflicts that occurred during the process of neolithization between the various tribes, ethnicities, and nations, and those which were already advanced in the Chalcolithic gave rise to the fully urban society, that is, to an organic society in the Durkheimian sense.

Sociologists, historians, anthropologists, and specialists in the sciences of religions are the ones who have most closely pointed out the correlation and even the shared identity between historical episodes and characters and ontological–religious configurations and characters, as is evident in the struggle between the old and the new gods33.

The physiology of women is the union of the ontological moment of the process of the generation of life and the empirical moment of the birth of individuals, and the moment in which the Titanomachy and the formation of society, as a single process, is described in two different ways, i.e., a symbolic religious and empirical war.

The woman is the one who captures this double moment of pain and suffering, on the one hand, and of joy and triumph on the other. Creation, the beginning of being and life, encompasses this double moment of pain and suffering, on the one hand, and joy and triumph on the other. This is the meaning given in Christianity to sin, death, and the pains of childbirth, and also to the birth of life, natural or supernatural, and to resurrection.

This is the way Friedrich Nietzsche understands the figure of Dionysus.

“For it is only in the Dionysian mysteries, in the psychology of the Dionysian state, that the fundamental fact of the Hellenistic instinct is expressed: its “will to life”. What did the Hellenes guarantee themselves with these mysteries? Eternal life, the eternal return to life; the future promised and consecrated in the past; the triumphant yes to life beyond death and mutation; true life as total survival, through procreation, through the mysteries of sexuality. Hence for the Greeks the sexual symbol was the venerable symbol in itself, the very depth in all ancient piety. Every detail relating to the act of procreation, pregnancy and childbirth aroused the highest and most solemn feelings. In the doctrine of the mysteries pain is sanctified: the “pains of the woman in labor” sanctify pain in itself; All birth and growth, all that guarantees the future, determines pain… In order for there to be eternal enjoyment of creation, for the will to life to affirm itself eternally, there must also necessarily be eternally the “agony of the woman in childbirth…” All this contains the meaning of the word “Dionysus”; I know of no higher symbolism than this Greek symbolism, that of the Dionyses. In it, the deepest instinct for life, the instinct for the future of life, the eternity of life, is religiously felt, and the path to life itself, procreation, is the holy path.

[…] Saying yes to life, even in its strangest and most painful problems, the will to life rejoicing in its own inexhaustibility in the sacrifice of its highest types: this is what I have called Dionysian, what I have guessed as the key to the psychology of the tragic poet”34.

The intermediate world is described by science as a moment of eternal return in various ways35, and there are also various ways in which philosophy and theology, sociology, and history describe it in workshop terms.

As far as science is concerned, eternal return is the temporal process that describes a physical system, from the initial moment of maximum potential energy to the moment of zero potential energy, when the same process or a similar one begins again. According to the laws of thermodynamics, this is the case of the universe, if it is a closed system, and it begins again and again depending on external energy factors.

Eternal return is the loop that physical systems describe when they are observed from the point of view of energy, i.e., of an initial energy, followed by its wear and tear and replacement. It is found at all levels of the physical universe, from elementary particles to neurons, from inorganic entities and through successive ascending loops, to biological and intellectual life.

In the formation of particles and atoms, there is an accumulation of elements in certain spaces (phase spaces) up to a certain degree, and then the space loses its energy and then recharges itself, according to a process described in the so-called Poincaré36 recurrence theorem, which Tipler explains clearly because he believes that the Omega Point, the end of the world and the resurrection, occur according to this formal scheme.

The loop or recurrence can be generalized, and it can also be examined in various metabolic processes of cells (for example in mitochondria, in the alternation of high ATP energy and low ADP energy)37, or in the homeostasis of living organisms38.

Chaos, indeterminate matter, or the quantum vacuum are, ultimately, the starting and ending point of the various loops that comprise determinate matter (periodic table), organic matter (chemistry of life) and “psychic matter” both electrical, affective, and mental (human beings). This chaos and this initial emptiness is the maternal womb of nature to which all the creatures of the universe return, because they come from it.

“Remember, man, that you are dust and to dust you shall return” (Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris, Genesis 3, 19) is said in the Christian Lenten liturgy, in the celebration of Ash Wednesday39.

As regards philosophy, there are many interpretations of Christianity that take these theses, with which Nietzsche proclaims his atheism and discredits Christianity, as the true content and the authentic sense of the Christian doctrine on death and resurrection, starting with Max Scheler, probably the most illustrious of his supporters40.

Among the most recent interpretations of Nietzsche in this sense, it is worth highlighting that of Javier Hernández-Pacheco, Friedrich Nietzsche: study on life and transcendence, where, with a broad knowledge of Nietzsche’s work and Western metaphysics, it is shown that the most probable referent of Nietzsche’s thesis on Dionysus, and perhaps the only possible one, is Jesus Christ, the Christian doctrine of resurrection41.

This “Christian Nietzschean” point of view also emerges in some approaches of difference feminism, especially those of Luce Irigay, Julia Kristeva, Maria José Binetti, Anne Baring, and Jules Cashford, who articulate the empirical meaning of childbirth and its transcendental meaning, both from a philosophical perspective and from a Jungian psychological perspective42.

Woman lives in the intermediate world between the creator and the creatures, and is the guardian and guide of that world, as repeated in all mythologies and recounted in popular rural cultures.

5. Formal Outline of Soteriology: Family Relations and Ritual Incest

From a sociological, legal, philosophical and theological point of view, the expression “behold, I am the handmaid, let it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38) means “yes, I do”; it means granting consent which makes firm the marital bond that gives rise to family and society. It means my soul and my heart can embrace your omnipotence, all your power fits in my bosom, and all that I am and can be I give to you to generate infinitely.

Wisdom is first nothing; then, it is a matter subject to number and measure, and, therefore, it is life and being. Wisdom presides over the unfolding of life from the beginning, and, at the same time as it expands, it experiences the pain of a tearing apart.

Later and at the same time as tearing apart, life is multiplication, knowledge of good and evil, and struggle between the two, and alternation between joy and pain. Life, woman, is what mediates. The middle life between divinity and human beings is the feminine moment of creation and, for this reason, it is ontologically prior to the logos and has a certain autonomy with respect to form. For this reason, it can be chaotic, dangerous, and fearful. It can also have as an accomplice the tearing of form, which threatens it.

From the sociological historical point of view, it can be stated by saying that human history began with matriarchy in the Paleolithic period, as indicated by Banhoeffer, which continued in the process of neolithization, when the rise and domination of patriarchal society took place, reaching, for the moment, equality in terms of human rights.

Finally, wisdom is an ascending movement, the reditus or epistrophe, contrary to the second law of thermodynamics, and triumph over it, that is, over death. The living return to primordial matter, i.e., a return to the beginning of the cosmos, and withdraw again into nothingness, only to re-emerge later in a new life beyond being and nothingness, next to the One. From the sociological point of view, this already belongs to the empirical existences of present and future individuals.

The maternal beginning is wisdom that generates with the help of the logos. “In Sanskrit, mother is called matr and designates both the one who generates life and the one who measures and knows what is generated. From there comes matra: womb and measure; matih: measure and exact knowledge; mimati: to measure. Mathematics means, by derivation, the knowledge or wisdom of the mother”43.

In Proto-Indo-European languages, mother is written as *méh₂tēr (cf. Irish máthair, Tocharian A mācar, B mācer, Lithuanian mótė). Other linked languages include Latin māter, Greek μήτηρ, Common Slavic *mati (hence, Russian мaть (mat’)), Persian مادر (madar), and Sanskrit मातृ (mātṛ)44.

The first two versions of this process are ritual and mythological, as has been said, while the third is philosophical and theological and the fourth mystical. In the ritual and mythological versions, expansion and multiplication is an exit and also a painful tearing, as if fertility carried with it the impurity of the woman. Incest also has this double valence—either it is the maximum imitation of divinity or it is the most abominable of sins.

This is the key to the connection of woman with evil, the ambivalence of the chaos in which matter and she consist, and which can give rise to an infinity of splendid forms or to a certain amount of deformed, untraceable, and sterile entities, doomed to extinction or death, whether thermal death, biological death, or spiritual death.

The infinite power, the prote apeiría of Plotinus and Proclus, the first substance and the Eve of Ibn Gabirol, the Great Mother, which the Phoenicians designate with the name of Astarte or Inanna, the Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians with that of Ishtar, and the Hindus as Pavarti (Maya), is, on the one hand, life and fertility, and, on the other, perversion, but not as two different divinities, but as one with the same name, like Astarte, or the same person with the same name or two different names, like Parvati: Durga, which expresses maternal love and Kali, which expresses wickedness45.

The Greek Athena has this intermediate character between good and evil, because she is the goddess of care and the art of healing (Hygieia), but also of just war, prudence, and cunning. On the other hand, Eve, the first Jewish and Christian mother, differentiated from the previous ones because she is not a divine being but a human creature, also has this intermediate character, because she is the origin of evil, and, at the same time, the mother of all living beings.

In all cases, the entire universe, matter and life, which arise from the beginning as chaos in what Plotinus calls proodos, returns again to chaos in death, to return from there again to the beginning beyond chaos, in what Plotinus calls epistrophé.

From the biopsychological point of view, the process can be understood in the same way. The scheme of the Great Mother, in her fecundity and tearing, is repeated in all the beings from which the others originate, in the atoms and molecules, in the first plant life, in the first animals, and in the first psychic processes of the formation of the unconscious and of consciousness.

“The subjective unconscious understands the maternal archetype as an origin torn apart by its loss and restored by the continuous actuality of existence. In both its cultural and subjective dimensions, reproduction, birth, the division of the maternal womb suppose a difference that, without abandoning the immanence of the origin, generates its constant reaffirmation: that circle in which the ex and the ad utero are reciprocally reversed”46. Parto means, at the same time, division, creation, and fall.

This circular scheme of the biopsychological process seems to operate also in the historical order, every time a cultural crisis occurs and every time it is overcome, in what Vico calls the “corsi e ricorsi” of the development of humanity.

The crisis of modernity seems to be an exhaustion of the scheme of historical linear time and progress, of what Derrida designates as the phallogocentric scheme, and a return to the beginning of thinking, i.e., to the origin, as is evident in the thought of Husserl, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein.

“This origin is the reproduction of the maternal womb, its creative unfolding, the birth of its unity, not the two of an extrinsic linearity, but the three of its repetition. Such is the medium, the mediation of an existence that flows back to its own being. Because we live, move and have our being in the womb of the mother, reality justifies itself in the eternal return of a newborn origin. The time of the mother is the time of birth that occurred in the instant of that essential memory, towards which contemporary thought seems to be returning”47.

These characteristics of wisdom and the maternal womb, which appear in cosmological, biopsychological, and historical analyses, also appear in the perspective of Chalcolithic mythology, in that of mystical Pythagoreanism, and in that of the Kabbalah, where the feminine and evil are associated.

The association of the feminine with good and evil occurs in various ways. In Anaximander’s approach, indeterminacy is the infinite as a universal good, and in Pythagorean approaches the Dyad is the first attack on unity, the original sin, which engenders otherness, an ontological audacity (tolma), which occurs in each emanation.

This Pythagorean thesis is taken up by Plotinus, for whom matter, the feminine, is the possibility of the illusion of an existence separated from the One (appearance, the goddess Pavarti or Hindu Maya), and is the root of all forgetfulness and evil (1 Enneads V, 1, 10). The Dyad, multiplicity, is both fecundity and a tear, hybris.

Proclus insists that Maya, appearance, is the cause of souls forgetting their father, God, and ignoring themselves, but matter does not imply evil in itself, so much as infinite indeterminacy. Only when it enters the order of determination, of the knowledge of the illusory as knowledge of good and evil, does “audacity (tolma)” occur, i.e., the birth of the first otherness and the desire to belong to oneself (On the Existence of Evil, 12, 10–15)”48.

This Neoplatonic Pythagorean mystical approach continues in Kabbalah. The first noetic sefira, Hokhma/Wisdom, is the undifferentiated, unifying nature of prime matter and contains no evil. Opposite it arises the Dyad as Binah, as “Intellection” or “Dissociating Intelligence”. This is why the heavenly Mother of duality/plurality is sometimes seen as the source of metaphysical evil, not directly, but, similarly to Proclus’ dyad, “as a by-product, through her participation in the psyche and thus through her role in nourishing the illusion of autonomous existence”49.

For Anaximander, Proclus, and Kabbalah, matter, the infinite/indefinite, positively connotes original perfection, so that infinite power is feminine. For Pythagoras, on the other hand, the Unlimited, the apeiron, is, as in Aristotle, the Dyad that rebels against the One (Proclus, Teologia platonica. vol. I, book IV, chap. 10).

The Pythagorean tradition, which identifies chaotic and indefinite matter with the indefinite Platonic dyad and the primordial material substance, is reinforced by Orphic cosmology. In all these philosophical and mythological traditions, the primordial feminine principle is infinite in a negative sense: that is, it is infinitely or indefinitely divisible and, therefore, weak, compared to the modern positive infinite, which is usually synonymous with power.

The unifying, individualizing, and, therefore, “powerful” element, that is, the form, “has come to all things from the Monad and the Limit, [while] the endless aspect of the procession has come from the generative Dyad. (Proclus, On Plato’s Cratylus, in 385E4–386D7). This Plotinian Pythagorean scheme is transposed into the discrete ontology of Aristotelianism, where, once again, perfection is not the original infinity of possibilities, but the limitation”50.

“The metaphysical notion of power becomes, with Aristotle, univocally masculine and exterior, while the ideas of flow, germination and organic growth, which are no longer applicable to the first principles, are relegated to the lower manifestations of the psyche (animals, the vegetative). The feminine is thus reduced to the passive and weak (inferior) aspects on the one hand, and to the chaotic, and therefore equally “weak”, forces of the apeiron on the other”51.

In continuous ontologies, where the original infinity is equated with the indeterminacy of the One, the Dyad became synonymous with limitation, plurality, and manifestation.

In more discrete ontologies, on the other hand, indefiniteness, negatively connoted, tends to be identified with the feminine principle, while the limit is seen (as in the Pythagorean categorial scheme) as a masculine aspect. The Kabbalistic tradition is obviously closer to the continuous ontology of Anaximander and Proclus than to the discrete ontology of Pythagoras and Aristotle.

“Stripped of its numerous feminine connotations, the Dyad is equally associated with Christ, in the flow from the Monad to the Triad, as the manifest aspect of the Unknowable Father, with “orthodox” Greek theologians such as Gregory of Nyssa, Maximus the Confessor, and later Gregory Palamas.

The first determinate and gendered emanation, the “left” sefirot Bina/Intellection, is thus defined as Door, Receptacle and Form, while its “right” correspondent, Hokhma/Wisdom, is an amorphous, indeterminate golem”52.

This is how fertility and destruction, the unfolding of life, of good and evil, are expressed in the ritual, mythological, ontological, and theological order. In turn, according to this diversity of perspectives, the rituals and doctrines on the role of Eve and Mary, and of the rest of the female figures in the salvation and redemption of society and of human individuals, are then diversified.

The history of feminist movements, although more than two centuries old, is less complex, but almost everything that has been said about feminist movements comes from work done mostly by women in the last two centuries.

6. Resurrection and Salvation: Regressus ad Uterum

Sacred marriage, or hierogamy, is found in almost all religions, and constitutes the formal scheme of soteriology: The human being acquires divine nature and life when the divinity acquires human nature and life, which happens in the offspring of the sacred union.

In Christianity, soteriology is expressed in a very technical formula elaborated at the Council of Nicaea: In Christ there is one divine person, and two natures, one divine and one human.

The birth from a virgin woman and from a human mother is also the case for Theseus, Aeneas, Genghis Khan, and other founders of peoples. The parallel texts of other religions on hierogamy and the virgin birth of the founder are equally numerous53.

By analyzing the characteristics of female impurity, its scope in personal and social life, and its universality in prehistory and history, the precocity with which sapiens discovered the mediating role that women play between the supreme creative power, divinity, and the individuals of the human species, and perhaps between the females of living species and the individuals of them, is revealed54.

When, at the dawn of the historical epoch, the creation of the universe began to be referred to from the point of view of the intellect and not of the imagination, women ceased to be represented with anthropomorphic images and began to be represented by abstract concepts, such as matter, infinite power, apeiron, proteusia, and others.

Initially, in pre-Socratic and Platonic reflection, these notions were designated as divinities, with different names and functions, such as Demiurge, the soul of the world, divine ideas, genders of being, the unlimited, space, and other names. Later, especially from Aristotle onwards, they were systematized by distributing their functions into four types of causes, namely material and formal, efficient, and final.

The physical and metaphysical description of the functions and activities of women corresponds to the liturgical ritual and the theological elaboration, which has as its setting the same intermediate world, where the final judgment takes place, and where Nicodemus’ question about salvation is answered: “Jesus answered him, ‘I tell you the truth, no one can see the kingdom of God unless they are born again’. How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter his mother’s womb and be born again?” (John 3:3–6).

When a man dies and returns to the dust, to the earth, to the bosom of Mother Nature, he returns to the intermediate world, to the place where “women received their dead by resurrection” (Hebrews 11:35). That is why it can be thought that the womb of the cosmos, of the primordial mother, of the Immaculate Conception, is symbolized by the maternal womb, to which the living return when they die, identified with the maternal womb from which they arise.

The regressus ad uterum is not only a psychological and symbolic event, as described by Ferenczi, Freud, or Jung. It is also the physical event described by Tipler and quantum physics, and the moment of religious events described as transmigration, purgatory, or purification in general, as described in the different creeds and confessions.

Modern science does not have the resources to describe the events of the intermediate world, but the mathematics and physics of the 20th and 21st centuries do. Furthermore, it can describe them in a less polyvalent and more univocal way than psychology, and, on the other hand, as more referable to empirical, debatable, and falsifiable verifications, as is the case with Tipler’s proposal.

On the other hand, where the events of the intermediate world appear most clearly is in the sociological perspective. These events are maintained in folklore, myths, and popular culture, they belong to common experience, and they are carried out by entities that, although they may belong to everyday life in some times and cultures, cannot be legally questioned because they do not have an official identity in the public interpretation of reality.

They are the souls in torment, the ghosts, the souls in purgatory, etc., who can interact privately with the living, or publicly at parties where this communication “officially” takes place, such as those of the Anthesteria in ancient Greece55, those of Hamsain and Halloween in the ancient Celtic world and in the contemporary Anglo-Saxon world56, the festivals of All Saints’ Day in Christianity57, the Day of the Dead in some Latin American countries, and other similar ones in different cultures.

In the historical period and with the development of cities, the festivals become more differentiated, and with Christianity new factors of diversification appear.

In the 9th century, the date of 1 November was set among the Franks, and in the 11th century, the 2 November was set as All Souls’ Day in the Carolingian Empire. This is how the celebration of the three festive days began, with the first being Allhallowtide, the Eve of All Saints (31 October), the second being All Saints’ Day (1 November), and the third being All Souls’ Day (2 November, as included in the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and Anglican (Episcopal) liturgical calendars.

In the 16th century, Catholic rites for the dead were established in Latin America58, where they are celebrated as a happy day with elaborate and joyous festivities unique to each region59. In 2008, UNESCO declared the festival an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in Mexico.

Ghosts, souls in torment, and souls in purgatory are the most prominent actors in these moments, together with impure spirits (demons) and various kinds of women, including witches, sorceresses, magicians, fairies, and others. These are the most familiar inhabitants of the intermediate world, and there is no lack of historical, sociological, and anthropological documentation.

In the oldest celebrations, from the 6th century BC and earlier, all the actors participate in the same event, namely, the death, dismemberment, and ingestion of the divinity, the purification of the souls of mortals, drunkenness, and the resurrection of the god. These events take place on the same stage and women are the special protagonists.

The first testimony and the first description of a ghost, which remains as a specific icon to this day, is due to Pliny the Younger, and later references refer to that model60.

When Tertullian and Plutarch describe the Anthesteria festivals61, describe the souls in torment and ghosts, the soul (psyche) of the deceased to which the spirit (pneuma and nous) may remain attached, without its body (soma or sarx). These souls relate to the living according to well-established protocols, but also with complete naturalness and freedom.

The soul in torment is designated by Plutarch, sometimes with the term psyche, i.e., without more, and at other times with the term eidolon, which is translated as “ghost”, and other times with the term phásmati, which is translated as “spectre”62. Along with the “soul”, there often appears the “daimon” (genius in the Roman world), which is always a spiritual double of the deceased, different but associated with him, his personality, and his destiny.

Plutarch’s daimon is the daimon that appears in the Socratic dialogues. It corresponds to the personal divinity inseparably associated with each human being, each living being, or each real entity, not only in the Sumerian and Babylonian religions, but also in Hinduism and Japanese Shinto, and even among the Mapuches, and has its equivalent in the guardian angel of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In other works by Plutarch and by Tertullian, these three terms are not synonymous. Sometimes ghosts or specters are not souls of dead people but are satanic or completely fictitious beings.

The souls of the deceased who are in pain, and who return again and again to dialogue with the living, are incomplete souls because their lives ended abruptly.

In chapter LVI of De Anima, Tertullian systematizes the ghosts or souls in pain, which are frequently found in Greek and Roman feasts of the dead, into five large categories: (1) first of all, the souls of those who die in childhood, children; (2) those of women who die in bloom; (3) those of soldiers who die in battle; (4) those of people who die a violent death, among whom are military personnel, soldiers, combatants, criminals, etc.; and (5) those of people who die without burial and are left without the help of their loved ones63.

When Tertullian describes the most assiduous and persistent figures of the Anthesteria, he speaks of people whose life was somehow cut short from a biological and social point of view rather than cut short from a moral or religious point of view. Perhaps that is why he conceives the soul (psyche) as the beginning and form of materials that have not finished organizing themselves due to a lack of time.

Souls in torment seek help to reach a certain biological and social completion, for the lack of which they suffer a suffering different from the suffering of those who are morally reprobate. This is why their place is the intermediate world rather than in the world of the damned or the blessed.

In Greek and Roman culture, these are the souls in torment who need help, and in earlier periods this help was provided by the psychopomp. From the Chalcolithic onwards, when religions became urbanized and institutionalized, help was provided by institutionalized religions in public ceremonies, but private practice did not disappear.

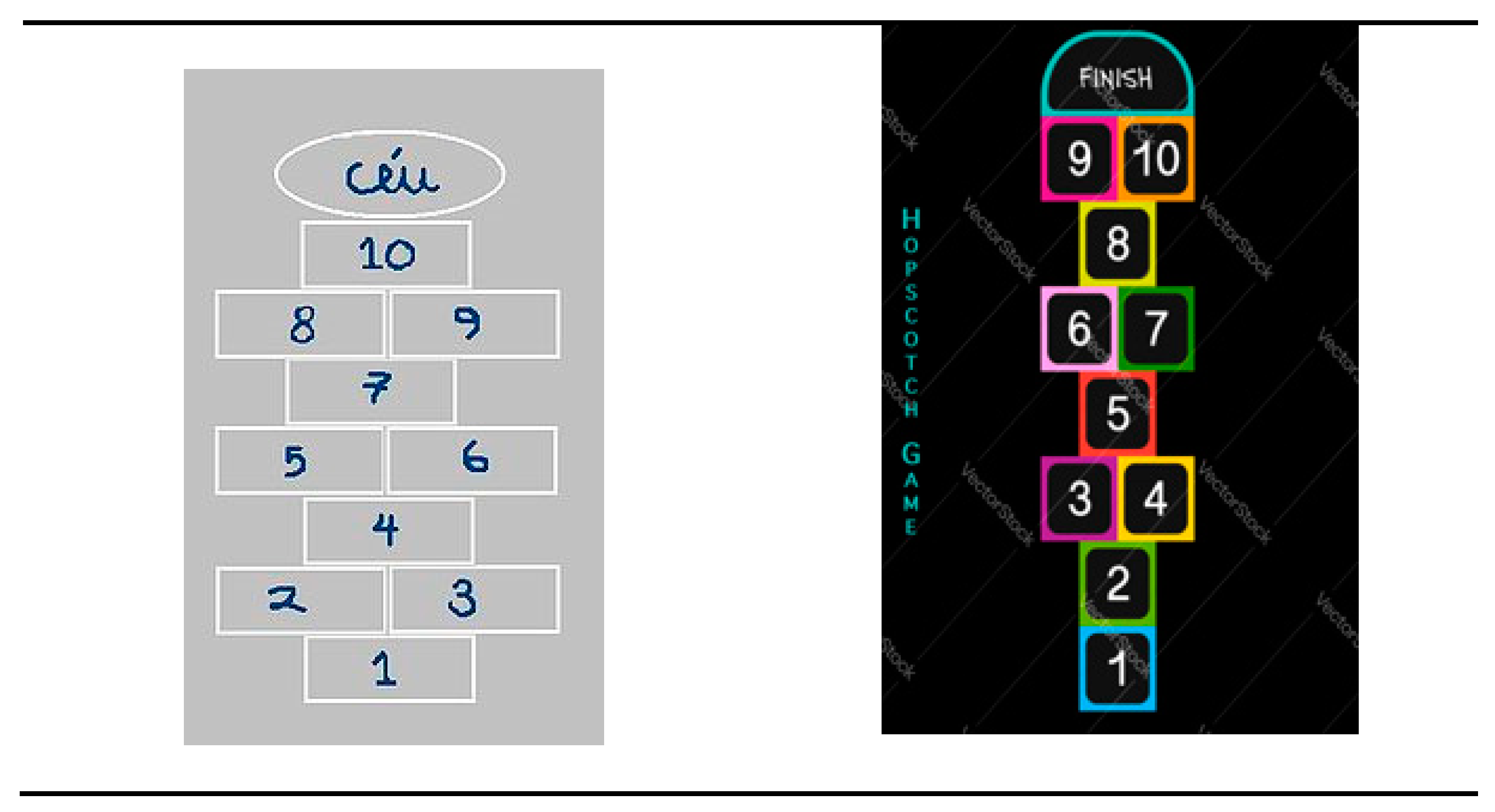

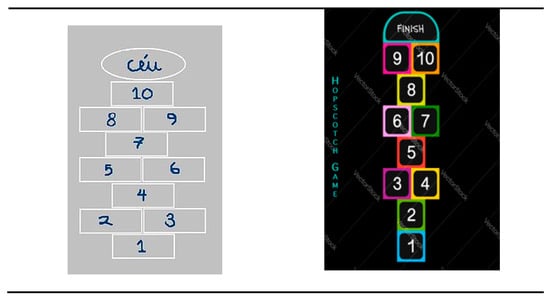

This practice continues to exist privately, but it is also universally included in a type of children’s game, which remains practically unchanged to this day, and which receives various names depending on the country and language.

In the English-speaking world, it is called Hopscotch (Scottish jump), in Italy it is called “Il Gioco del Mondo”, and in Spain it is called “la rayuela” (see Figure 4). It is mainly practiced by girls and consists of carrying a small stone, which symbolizes the soul of the deceased, from the beginning of the route to its final square, which is usually called the “sky”64.

Figure 4.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hopscotch (accessed on 10 February 2025).

It seems that all over the world, girls before the age of reason play at being mothers and bringing men from the intermediate world into the empirical world, and, from the age of reason to adolescence, they play at bringing the souls of the deceased to their proper place in the intermediate world, until they reach their final destination.

The sacredness of the feminine consists of its position and its intermediate activity between the creative and saving action of man on the part of divine action, and the existential journey of human beings from birth to death, and from the moment of their death to the parousia, i.e., to the final judgment and eternal life.

When the feminist movement was born, it came into being as a feminism of equality and confronted the ontological theses on which the privileges of the Ancien Régime were based. Freedom, equality, and dignity are proclaimed in juridical terms in the sociological and political order, and sometimes disregarding their ontological dimension, which is linked to the religious values that are the stronghold of the Ancien Régime.

As feminist thought becomes broader and more reflective, both sociologically and ontologically, and when equality is sufficiently achieved in the formal order, ontological differences begin to become visible, both in the sociological order of rites, religion, and folklore, and in the ontological order of theoretical reflection.

So, what does the difference or confrontation consist of? To say that one is a man or a woman because one is born from a zygote developed in a uterus may seem very different from affirming that one is a man or a woman because that is how it is recorded in a civil registry.

But law flees from ambiguity as much as any other art or science, and seeks a sufficiently perceptible foundation for its definitions to be enforceable against third parties. The law determines the position and identity of each individual in the social and legal sphere

When looking for this foundation, one always arrives at the zygote and the uterus, even if they were obtained synthetically, and there is the justification for registration in the civil registry, i.e., their position, according to their identity.

One could analytically go through the set of all the processes ranging from LUCA (last universal common ancestor, an acronym in English that refers to the last universal common ancestor), to the embryo, and the human individual in question. Or it would even be possible, in the opposite direction, to go back to the quantum vacuum before the Big Bang, from which LUCA would emerge.

Since the set of these processes is not known, it is not possible to deploy them analytically in fact, but it is possible in theory, because a sufficient number of maximum and minimum forces, of stages, of groups, of sets of units, of superpositions, and of hierarchies, are known, so that it is difficult not to assign them substantial ontological values, both causal and accidental.

That is to say, it is difficult not to assign unity, identity, efficiency in itself, and a result (purpose) to the atom, to the molecules, to various organic formations, to the chromosomes, to the zygote, to the pregnant entity, and to the gestated individual.

These units with ontological value have been called, since ancient times, celestial spheres, infinite matter, the soul of the world, individual substance, self-consciousness, etc., and in the mathematics and physics of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries they are described with terms, such as attractors, automorphic functions, self-catalysis, nucleic acids, genome, ontogenetic unit, and phylogenetic effect. If both systems of denominations are unified, theses appear in which the feminism of difference and that of equality are indiscernible.

If the unification of the two systems of categories is avoided and they are used only with those of an empirical type with a sociological and political approach, they result in theses quite similar to those of equality feminism.

The feminine sacrum is included in both approaches and designated with a word that in neither case loses its sacred character, namely, the word “mother”.

The word “mother” has been defined since time immemorial as “the one who gives birth”, that is, the protagonist of a natural process. As a result of sociotechnological innovations, Western legal systems are now faced with the task of formulating a new legal definition: “mother is the one who has the will to beget”, that is, the protagonist of a personal, voluntary, and free process65.

Does the word “mother” lose its deep and sacred meaning when it leaves the juridical definition of “she who gives birth” and takes up that of “she who has the will to beget”? The ontology of the feminine seems to remain the same through sociotechnological changes, and it seems that the ancient Roman principle of “mater certa est” is still valid.

Funding

This research received no external.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Chausidis 2012; Čausidis 2020, pp. 61–62). |

| 2 | (Heisenberg 1959). |

| 3 | Potencia infinita (ἄπειρος δύναμις, ápeiros dýnamis; (Plotino [1982] 1985)). |

| 4 | (Zellini 1980). |