Genomic Characterization of KPC-31 and OXA-181 Klebsiella pneumoniae Resistant to New Generation of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Neil, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: London, UK, 2016; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaboratos. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655, Erratum in Lancet 2022, 400, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. WHO Pathogens Priority List Working Group. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206494s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- FDA Approves Antibiotic to Treat Hospital-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Bacterial Pneumonia. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-antibiotic-treat-hospital-acquired-bacterial-pneumonia-and-ventilator-associated (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Hayden, D.A.; White, B.P.; Bennett, K.K. Review of Ceftazidime-Avibactam, Meropenem-Vaborbactam, and Imipenem/Cilastatin-Relebactam to Target Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. J. Pharm. Technol. 2020, 36, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaibani, P.; Giani, T.; Bovo, F.; Lombardo, D.; Amadesi, S.; Lazzarotto, T.; Coppi, M.; Rossolini, G.M.; Ambretti, S. Resistance to Ceftazidime/Avibactam, Meropenem/Vaborbactam and Imipenem/Relebactam in Gram-Negative MDR Bacilli: Molecular Mechanisms and Susceptibility Testing. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehmann, D.E.; Jahic, H.; Ross, P.L.; Gu, R.-F.; Hu, J.; Durand-Réville, T.F.; Lahiri, S.; Thresher, J.; Livchak, S.; Gao, N.; et al. Kinetics of avibactam inhibition against class A, C, and D -lactamases. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 27960–27971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, C.; Butera, O.; Meledandri, M.; Balice, M.P.; Cocciolillo, G.C.; Fontana, C.; D’Arezzo, S.; De Giuli, C.; Antonini, M.; Capone, A.; et al. Molecular analysis of clinical isolates of ceftazidime-avibactam-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1040.e1–1040.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.K.; Chen, L.; Cheng, S.; Chavda, K.D.; Press, E.G.; Snyder, A.; Pandey, R.; Doi, Y.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Emergence of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance Due to Plasmid-Borne blaKPC-3 Mutations during Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02097-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, V.; Monaco, M.; Giani, T.; D’Ancona, F.; Moro, M.L.; Arena, F.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Rossolini, G.M.; Pantosti, A. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from invasive infections in Italy: Increasing diversity with predominance of the ST512 clade II sublineage. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 3386–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgiu, G.; Are, B.M.; Pesapane, L.; Palmieri, A.; Muresu, N.; Cossu, A.; Dettori, M.; Azara, A.; Mura, I.I.; Cocuzza, C.; et al. Nosocomial transmission of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Italian university hospital: A molecular epidemiological study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 99, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, G.; Clancy, C.J.; Shields, R.K.; Hao, B.; Cheng, S.; Nguyena, M.H. Mutations in blaKPC-3 that confer ceftazidime-avibactam resistance encode novel KPC-3 variants that function as extended spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02534-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, A.; Mansour, W.; Tilouche, L.; Châtre, P.; Drapeau, A.; Chaouch, C.; Azaiez, S.; Bouallègue, O.; Madec, J.Y.; Haenni, M. First report of carbapenemase OXA-181-producing Serratia marcescens. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 26, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp-Wallace, K.; Endimiani, A.; Taracila, M.; Bonomo, R. Carbapenems: Past, Present, and Future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.L.C.; Romano, M.; Kerry, L.E.; Kwong, H.S.; Low, W.W.; Brett, S.J.; Clements, A.; Beis, K.; Frankel, G. OmpK36-mediated Carbapenem resistance attenuates ST258 Klebsiella pneumoniae in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumbreras-Iglesias, P.; Rodicio, M.R.; Valledor, P.; Suárez-Zarracina, T.; Fernández, J. High-Level Carbapenem Resistance among OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with Functional OmpK36 Alteratons: Maintenance of Ceftazidime/Avibactam Susceptibility. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asten, S.A.V.; Boattini, M.; Kraakman, M.E.M.; Bianco, G.; Iannaccone, M.; Costa, C.; Cavallo, R.; Bernards, A.T. Ceftazidime-avibactam resistance and restoration of carbapenem susceptibility in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: A case series. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 27, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Bella, G.; Lopizzo, T.; Lupo, L.; Angarano, R.; Curci, A.; Manti, B.; La Salandra, G.; Mosca, A.; De Nittis, R.; Arena, F. In vitro activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against carbapenem-nonsusceptible Klebsiella penumoniae isolates collected during the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A Southern Italy, multicenter, surveillance study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 31, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Mendes, R.E.; Doyle, T.B.; Sader, H.S. Prevalence of carbapenemase genes among carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected in US hospitals in a five-year period and activity of ceftazidime/avibactam and compar-ator agents. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 4, dlac098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yin, D.; Han, R.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; Hu, F. Emergence and Recovery of Ceftazidime-avibactam Resistance in blaKPC-33-Harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae Sequence Type 11 Isolates in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71 (Suppl. 4), S436–S439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VITEK® 2 Microbial ID/AST Testing System. Available online: https://www.biomerieux-diagnostics.com/vitekr-2-0 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Clinical Breakpoints of EUCAST v.11.0. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Del Rio, A.; Muresu, N.; Sotgiu, G.; Saderi, L.; Sechi, I.; Cossu, A.; Usai, M.; Palmieri, A.; Are, B.M.; Deiana, G.; et al. High-Risk Clone of Klebsiella pneumoniae Co-Harbouring Class A and D Carbapenemases in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bio-informatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Mlst Tool. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Wyres, K.L.; Wick, R.R.; Gorrie, C.; Jenney, A.; Follador, R.; Thomson, N.R.; Holt, K.E. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E.; Wyres, K.L. Kaptive 2.0: Updated capsule and lipopolysaccharide locus typing for the Klebsiella pneumoniae species complex. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Watts, S.C.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.H.K.; Bortolaia, V.; Tansirichaiya, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Petersen, T.N. Detection of mobile genetic elements associated with antibiotic resistance in Salmo-nella enterica using a newly developed web tool: MobileElementFinder. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; Garcia-Fernandez, A.; Voldby, L.M.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Hasman, H. PlasmidFinder and pMLST: In silico detection and typing of plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.E.; Stoesser, N.; German-Mesner, I.; Vegesana, K.; Sarah, W.A.; Crook, D.W.; Mathers, A.J. TETyper: A bioinformatic pipeline for classifying variation and genetic contexts of transposable elements from short-read whole-genome sequencing data. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobials | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | ≥32 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | ≥128 |

| Cefepime | ≥32 |

| Cefotaxime | ≥64 |

| Ceftazidime | ≥64 |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | ≥32 |

| Meropenem | ≥16 |

| Imipenem | 8 |

| Amikacin | 32 |

| Gentamicin | ≥16 |

| Tobramycin | ≥32 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≥4 |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | ≥320 |

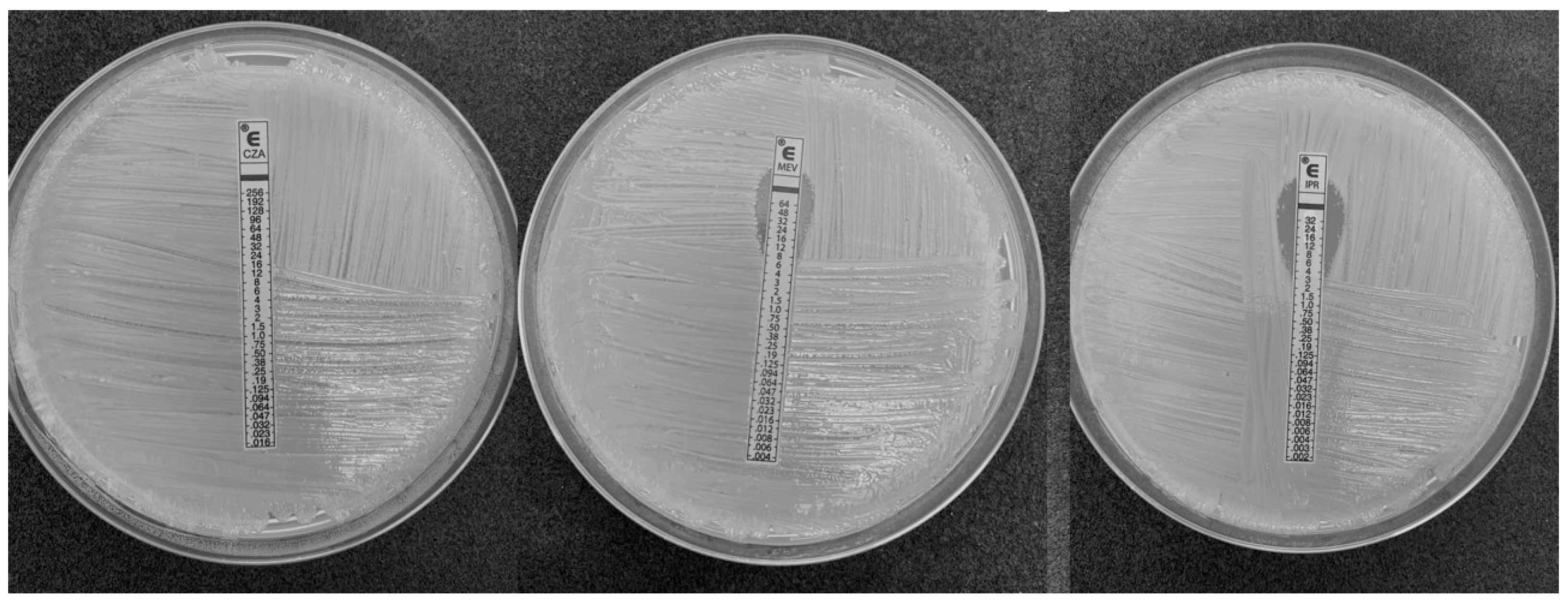

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 256 * |

| Imipenem/relebactam | 3 * |

| Meropenem/vaborbactam | 12 * |

| Antibiotics | Resistance Genes |

|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | aac(6’)-Ib4 |

| aadA * | |

| aadA2 ^ | |

| aph(3’)-Ia | |

| strA.v1 ^ | |

| strB.v1 | |

| Fluoroquinolones | qnrS1 |

| Macrolides | mphA |

| Chloramphenicol | catA1 ^ |

| cmlA5 * | |

| floR.v2 * | |

| Rifampicin | arr-2 |

| Sulfonamides | sul1 |

| sul2 | |

| Tetracyclines | tet(A).v2 |

| Trimethoprim | dfrA12 |

| dfrA14.v2 * |

| Β-Lactamases | |

|---|---|

| Class A | KPC-31 |

| TEM-1D | |

| SHV-11 | |

| Class C | CMY-16 |

| Class D | OXA-181 |

| OXA-10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muresu, N.; Del Rio, A.; Fox, V.; Scutari, R.; Alteri, C.; Are, B.M.; Terragni, P.; Sechi, I.; Sotgiu, G.; Piana, A. Genomic Characterization of KPC-31 and OXA-181 Klebsiella pneumoniae Resistant to New Generation of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12010010

Muresu N, Del Rio A, Fox V, Scutari R, Alteri C, Are BM, Terragni P, Sechi I, Sotgiu G, Piana A. Genomic Characterization of KPC-31 and OXA-181 Klebsiella pneumoniae Resistant to New Generation of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuresu, Narcisa, Arcadia Del Rio, Valeria Fox, Rossana Scutari, Claudia Alteri, Bianca Maria Are, Pierpaolo Terragni, Illari Sechi, Giovanni Sotgiu, and Andrea Piana. 2023. "Genomic Characterization of KPC-31 and OXA-181 Klebsiella pneumoniae Resistant to New Generation of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations" Antibiotics 12, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12010010

APA StyleMuresu, N., Del Rio, A., Fox, V., Scutari, R., Alteri, C., Are, B. M., Terragni, P., Sechi, I., Sotgiu, G., & Piana, A. (2023). Genomic Characterization of KPC-31 and OXA-181 Klebsiella pneumoniae Resistant to New Generation of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Antibiotics, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12010010