Ester Exchange Modification for Surface-Drying Time Control and Property Enhancement of Polyaspartate Ester-Based Polyurea Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

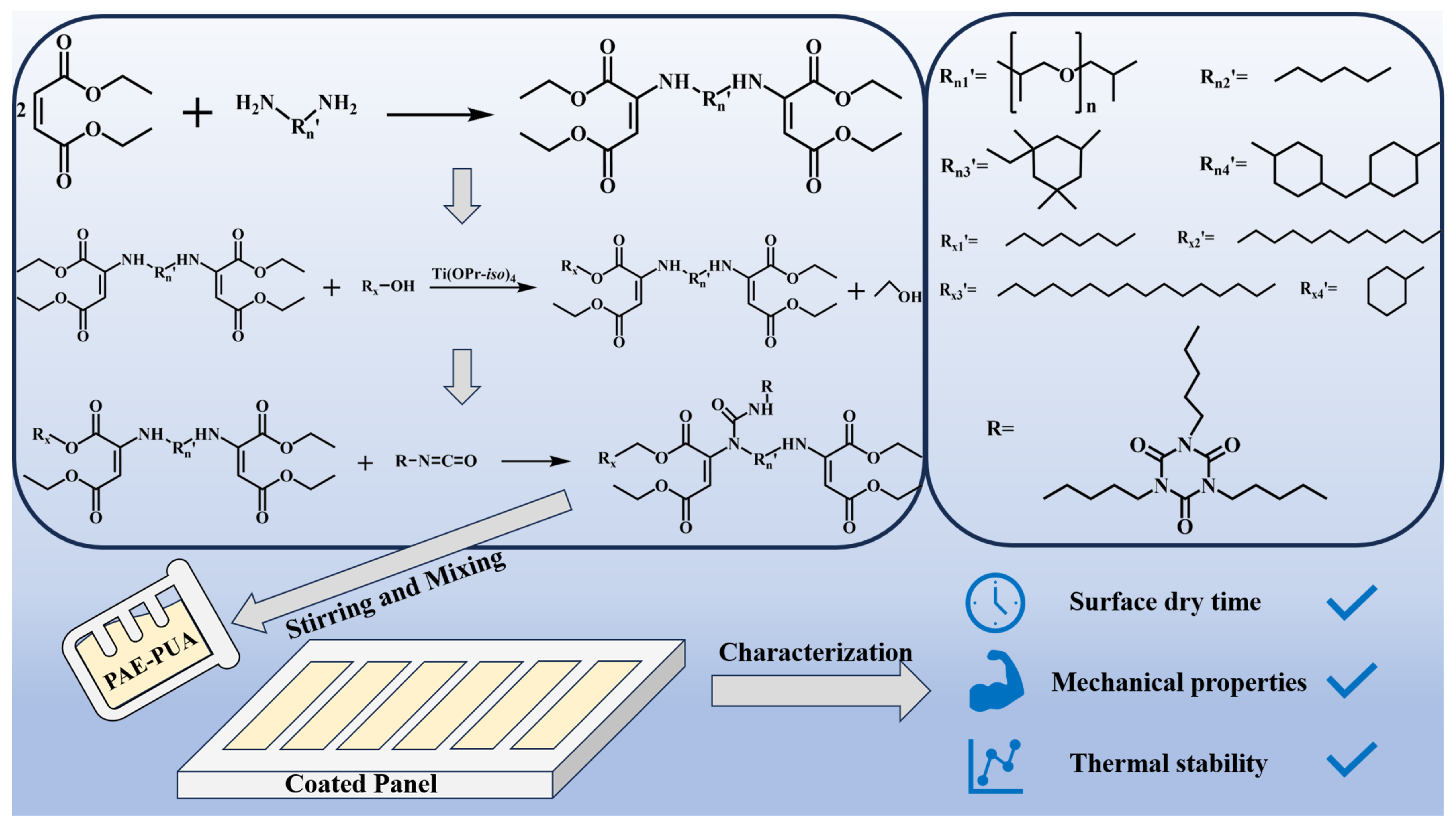

2.2. Synthesis of PAEs

2.3. Ester Exchange Modification of PAEs

2.4. Preparation of PAE-PUA Coatings

2.5. Characterization of PAEs Before and After Ester Exchange Modification

2.6. Performance Characterization of PAE-PUA Coatings

3. Result and Discussion

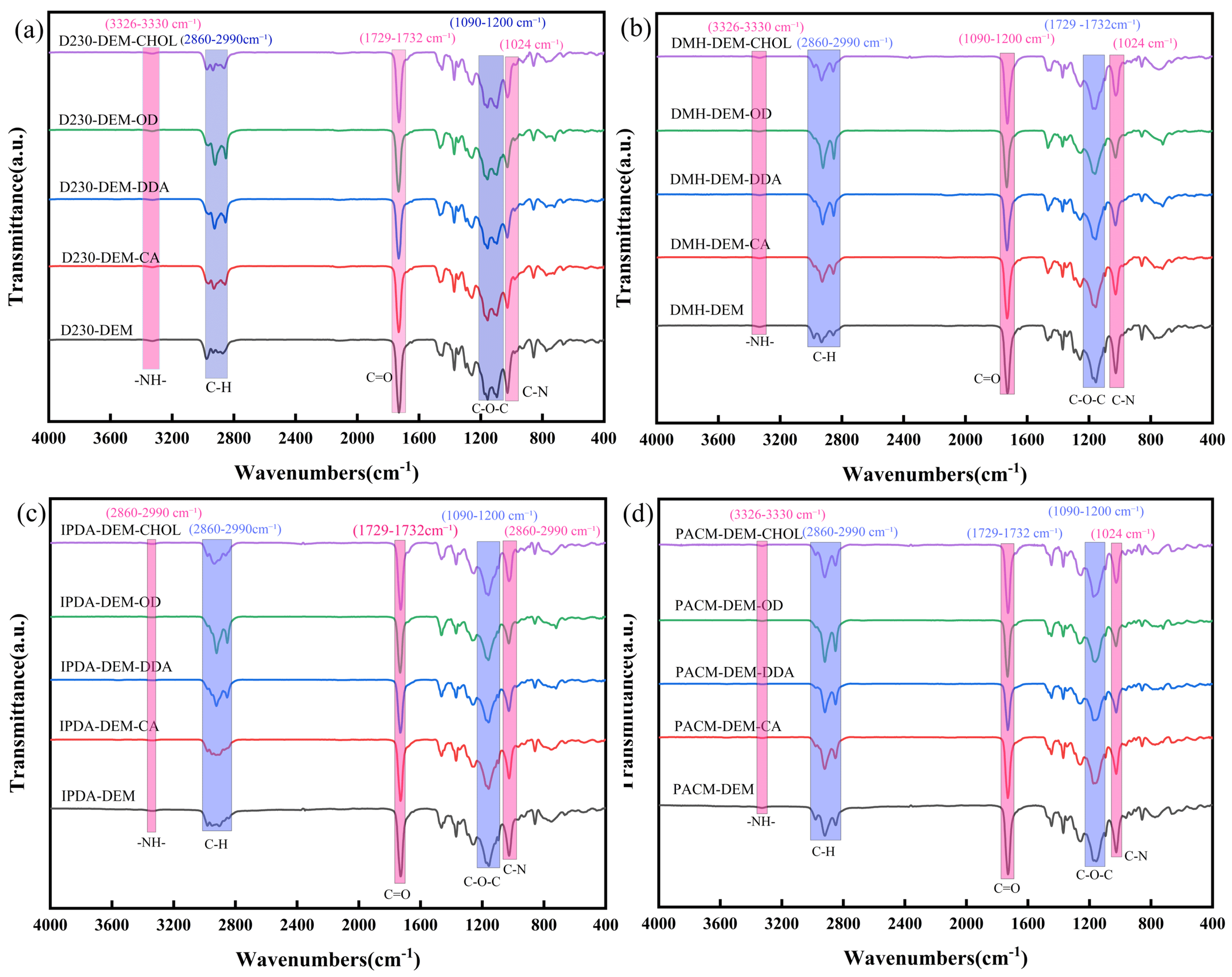

3.1. Structural Characterization of PAEs Before and After Ester Exchange Modification

3.2. Viscosity Characterization of PAEs Before and After Ester Exchange Modification

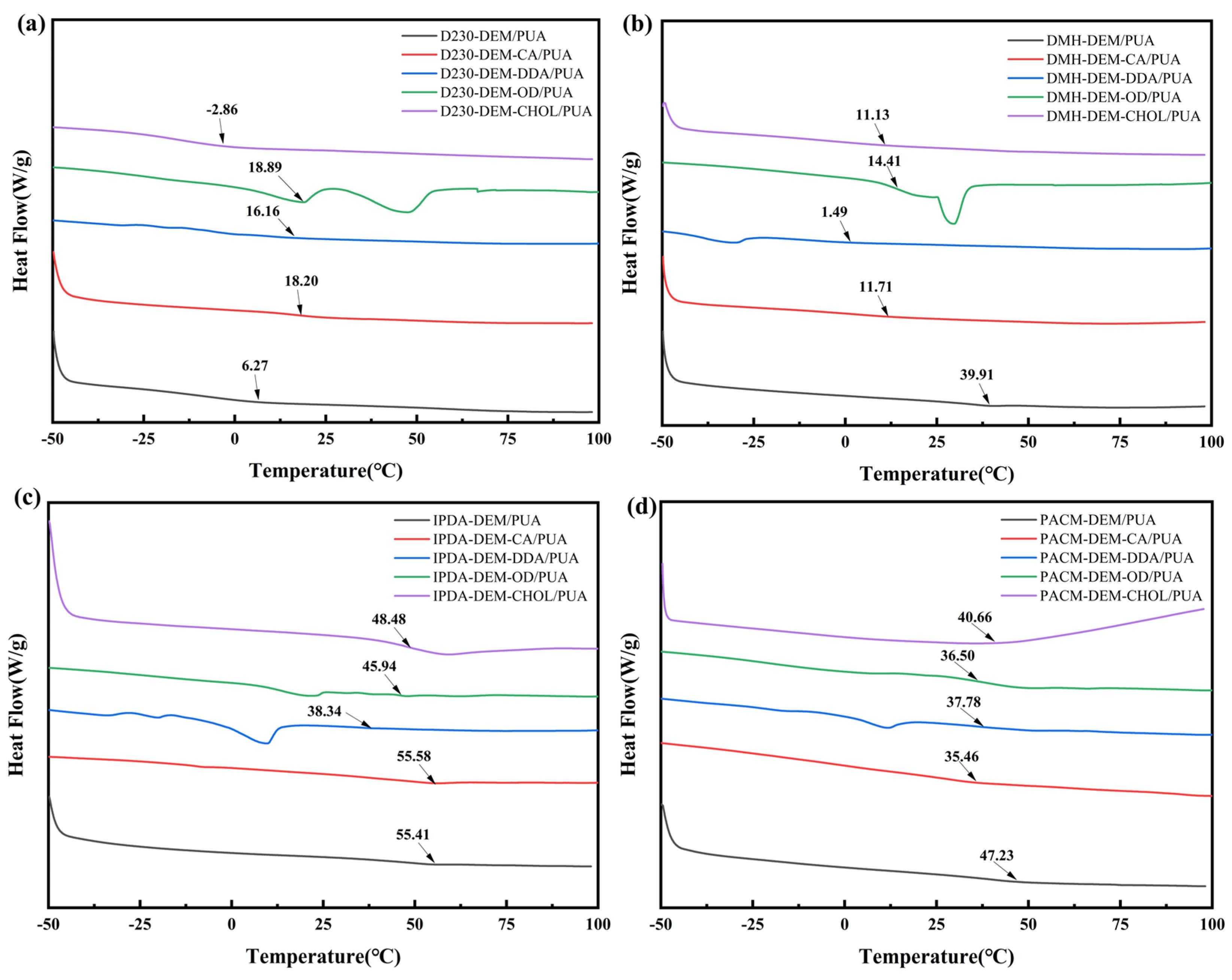

3.3. Performance Testing of PAE-PUA Coatings

3.3.1. Surface-Drying Time

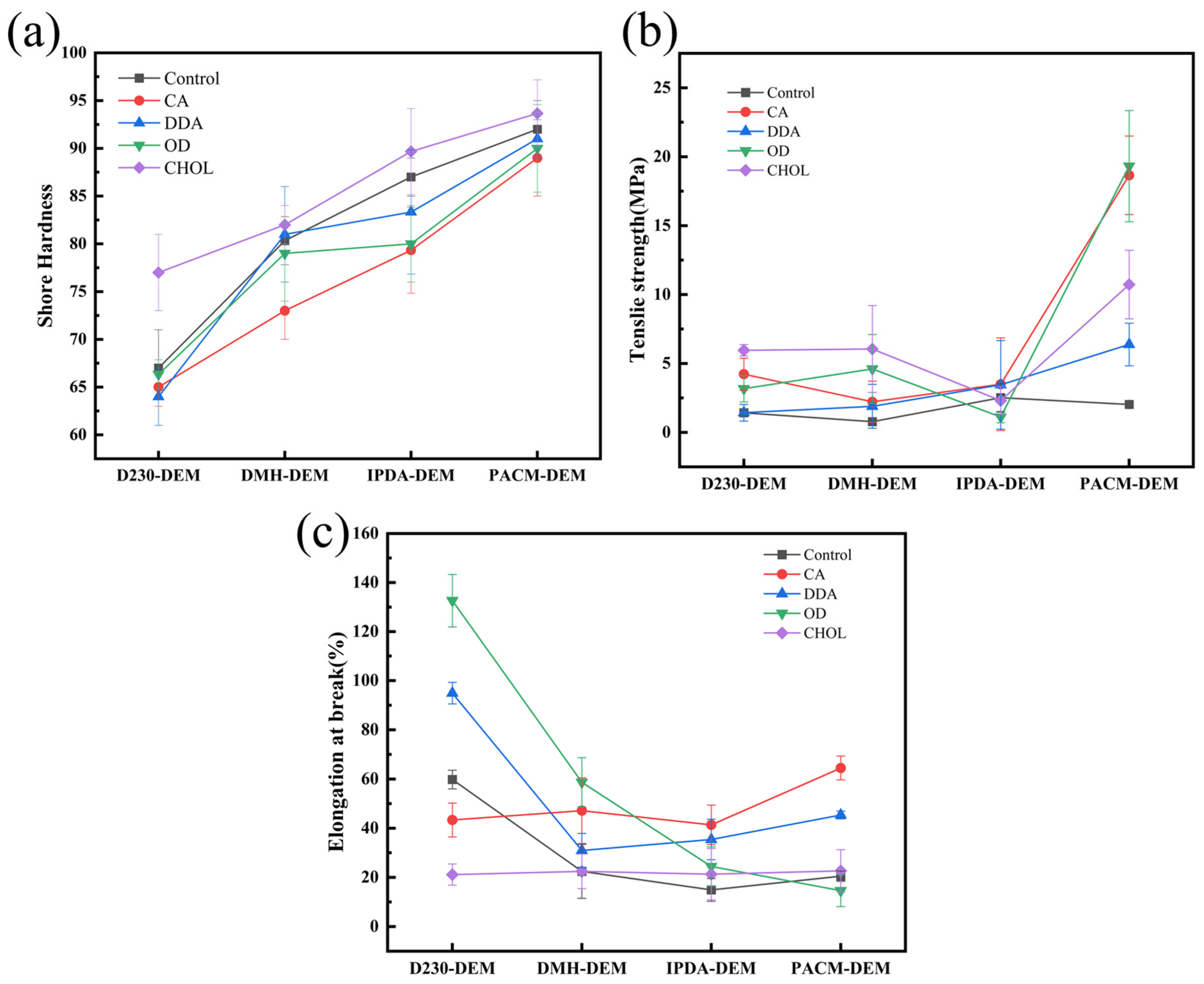

3.3.2. Mechanical Properties

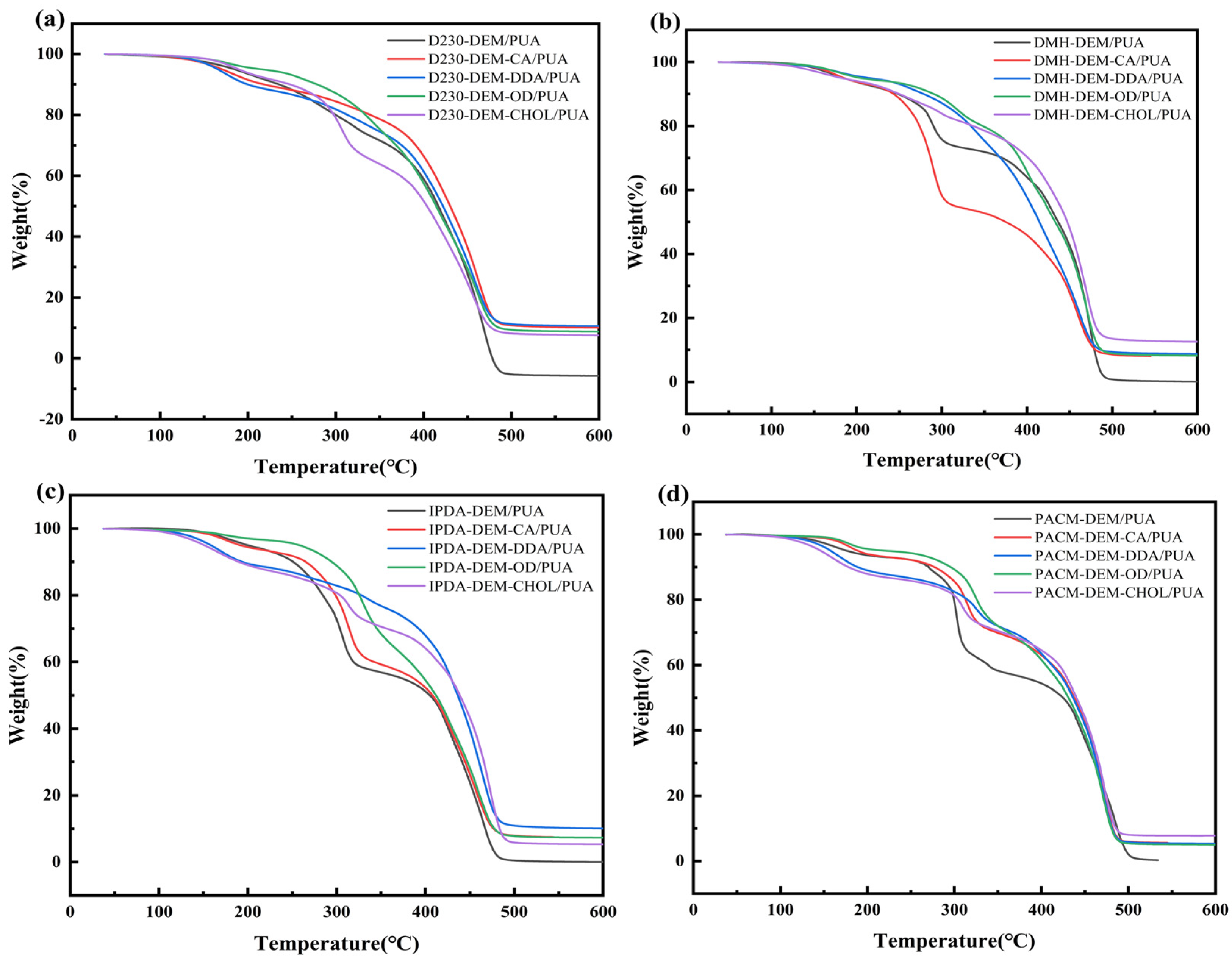

3.3.3. Thermal Stability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Compressive Behavior and Constitutive Model of Polyurea at High Strain Rates and High Temperatures. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 22, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, A.; Wang, H.; Ling, X.; Chen, G. Research on Dynamic Behavior and Gas Explosion Resistance of Polyurea. Msater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Tripathi, M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Kumar, D.; Roy, P.K. Polyurea Coatings for Enhanced Blast-Mitigation: A Review. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 109706–109717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, B.; Shang, J.; Deng, Y. Green Synthesis of Polyureas from CO2 and Diamines with a Functional Ionic Liquid as the Catalyst. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 54013–54019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Chiquito, M.; Castedo, R.; López, L.M.; Gomes, G.; Mota, C.; Fangueiro, R.; Mingote, J.L. Experimental and Numerical Study of Polyurea Coating Systems for Blast Mitigation of Concrete Masonry Walls. Eng. Struct. 2023, 284, 116006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlin, P.; Chahine, G.L. Erosion and Heating of Polyurea under Cavitating Jets. Wear 2018, 414–415, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stechishin, M.S.; Martinyuk, A.V.; Bilik, Y.M. Cavitation and Erosion Resistance of Polymeric Materials. J. Frict. Wear 2018, 39, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Youssef, G. Orientation-Dependent Impact Behavior of Polymer/EVA Bilayer Specimens at Long Wavelengths. Exp. Mech. 2014, 54, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Youssef, G.; Gupta, V. Dynamic Tensile Strength of Polyurea-Bonded Steel/E-Glass Composite Joints. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Citron, J.; Youssef, G.; Navarro, A.; Gupta, V. Dynamic Fracture Energy of Polyurea-Bonded Steel/E-Glass Composite Joints. Mech. Mater. 2012, 45, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, W.; Lyu, P.; Yan, S.; Wang, X.; Ju, J. Polyurea for Blast and Impact Protection: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, F.; Mota, C.; Bessa, J.; Cunha, F.; Fangueiro, R.; Gomes, G.; Mingote, J. Advanced Coatings of Polyureas for Building Blast Protection: Physical, Chemical, Thermal and Mechanical Characterization. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ning, S.; Yu, L.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Niu, J.; Fang, Q.; Kang, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; et al. Advances in the Design, Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of Polyurea. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 42, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, V.; Alizadeh, V.; Amirkhizi, A.V. Thermo-Mechanical Characterization of Polyurea Variants. Mech Time-Depend. Mater. 2021, 25, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.N.; Patel, M.M.; Dighe, A. Influence of Compositional Variables on the Morphological and Dynamic Mechanical Behavior of Fatty Acid Based Self-Crosslinking Poly (urethane urea) Anionomers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2012, 74, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadbin, S.; Frounchi, M. Effects of Polyurethane Soft Segment and Crosslink Density on the Morphology and Mechanical Properties of Polyurethane/Poly(allyl diglycol carbonate) Simultaneous Interpenetrating Polymer Networks. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 89, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, B.-S.; Schoen, P.E. Effects of Crosslinking on Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Polyurethanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 83, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wen, S.; Chen, K.; Xie, C.; Yuan, C. Study on the Synthesis and Properties of Waterborne Polyurea Modified by Epoxy Resin. Polymers 2022, 14, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuol, K.; Arendarchuck, B.E.; Rivadeneira, F.R.E.; de Castilho, B.C.N.M.; Moreau, C.; Stoyanov, P. Design and Development of Cost-Effective Equipment for Tribological Evaluation of Thermally Sprayed Abradable Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Du, M.; Fang, H.; Zhao, P.; Yao, X.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Y. A Molecular Dynamics Simulation on the Influences of PDMS on the Glass Transition Temperature and the Tensile Properties of Polyaspartate Polyurea. Polymer 2024, 300, 127016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Reaction Kinetics Analyses of Ethylenediamine Polyurea Curing Process. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 366, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Ma, M. Experimental Study on the Tension and Puncture Behavior of Spray Polyurea at High Strain Rates. Polym. Test. 2021, 93, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, K.; Lyu, P.; Wan, F.; Ma, M. Investigations on Aging Behavior and Mechanism of Polyurea Coating in Marine Atmosphere. Materials 2019, 12, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj, M.; Ubysz, A. The Reasons for the Loss of Polyurea Coatings Adhesion to the Concrete Substrate in Chemically Aggressive Water Tanks. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 142, 106774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, S.V.; Panov, Y.T.; Botvinova, O.A. The Influence of Isocyanate Index on the Physico-Mechanical Properties of Sealants and Coatings Based on Polyurea. Polym. Sci. Ser. D 2015, 8, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, S.I.; Yang, S.J.; Tsakeredes, N.J.; Fors, B.P.; Silberstein, M.N. Microstructural Evolution of Polyurea under Hydrostatic Pressure. Polymer 2021, 227, 123845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; You, Y.; Jia, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, P.; Xie, Q. Tensile Properties and Fracture Mechanism of Thermal Spraying Polyurea. Polymers 2022, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Y.; Tayama, K.; Okada, Y.; Kurokawa, M. Relationship between Sensory Saltiness Intensity and Added Oil in Low-Viscosity and High-Viscosity Polymer Solutions. J. Texture Stud. 2023, 54, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, F.; Gong, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Z.; Liu, G.; Li, X. Synthesis and Properties of Functional Polymer for Heavy Oil Viscosity Reduction. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 330, 115635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hu, L.; Dong, L.; Du, S.; Xu, D. Experimental Study on Anti-Icing of Robust TiO2/Polyurea Superhydrophobic Coating. Coatings 2023, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Ai, J.; Song, L.; Liu, B. Manual Applied Polyurethane-Urea: High Performance Coating Based on CO2-Based Polyol and Polyaspartic Ester. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 181, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, W. Microencapsulation of Oil Soluble Polyaspartic Acid Ester and Isophorone Diisocyanate and Their Application in Self-Healing Anticorrosive Epoxy Resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragiadakis, D.; Gamache, R.; Bogoslovov, R.B.; Roland, C.M. Segmental Dynamics of Polyurea: Effect of Stoichiometry. Polymer 2010, 51, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhou, C.; Fan, X.; Zheng, M.; Wang, S. Investigating the Rheological and Tribological Properties of Polyurea Grease via Regulating Ureido Amount. Tribol. Int. 2022, 173, 107643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 23446-2009; Spray Polyurea Waterproofing Coating. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- GB/T 528-2009; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic-Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Tripathi, M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Roy, P.K. Spray Processable Polyurea Formulations: Effect of Chain Extender Length on Material Properties of Polyurea Coatings. J Appl. Polym. Sci 2020, 137, 48573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhai, J.; Zhao, X.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Du, A. Effect of Temperature on Tensile Curve of Polyaspartic Ester Polyurea and Its Activation Energy Analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2101, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dural, S.; Camadanlı, S.Ş.; Kayaman Apohan, N. Improving the Mechanical, Thermal and Surface Properties of Polyaspartic Ester Bio-Based Polyurea Coatings by Incorporating Silica and Titania. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.T.; Lin, J.S.; Runt, J. Influence of Preparation Conditions on Microdomain Formation in Poly(urethane urea) Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| D230-DEM | DMH-DEM | IPDA-DEM | PACM-DEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 88 ± 5 | 132 ± 7 | 787 ± 30 | 1283 ± 150 |

| CA | 181 ± 5 | 151 ± 7 | 842 ± 40 | 957 ± 125 |

| DDA | 134 ± 5 | 171 ± 5 | 512 ± 35 | 717 ± 100 |

| OD | 297 ± 15 | 507 ± 35 | 987 ± 125 | 1172 ± 125 |

| CHOL | 474 ± 30 | 535 ± 30 | 3781 ± 300 | 4388 ± 500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, K.; Zhao, Q. Ester Exchange Modification for Surface-Drying Time Control and Property Enhancement of Polyaspartate Ester-Based Polyurea Coatings. Coatings 2025, 15, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020244

Yang X, Deng Y, Li P, Guo K, Zhao Q. Ester Exchange Modification for Surface-Drying Time Control and Property Enhancement of Polyaspartate Ester-Based Polyurea Coatings. Coatings. 2025; 15(2):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020244

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiandi, Yiqing Deng, Peini Li, Kaixuan Guo, and Qiang Zhao. 2025. "Ester Exchange Modification for Surface-Drying Time Control and Property Enhancement of Polyaspartate Ester-Based Polyurea Coatings" Coatings 15, no. 2: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020244

APA StyleYang, X., Deng, Y., Li, P., Guo, K., & Zhao, Q. (2025). Ester Exchange Modification for Surface-Drying Time Control and Property Enhancement of Polyaspartate Ester-Based Polyurea Coatings. Coatings, 15(2), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15020244