Abstract

The issue of corporate rent-seeking, which stems from the misuse of authority, remains a critical concern for the international community. Drawing on agency theory and resource dependence theory, this study explores the relationship between corporate digitalization strategies (DSs) and corporate rent-seeking. We test our theoretical hypotheses by utilizing panel data encompassing Chinese A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2021. Our findings suggest that corporate DSs have a significant negative influence on rent-seeking. Several robustness tests support this conclusion. Moreover, our analysis indicates that a DS is particularly effective in curtailing rent-seeking behaviors within state-owned enterprises (SOEs) compared with their non-state-owned counterparts. However, contrary to our hypothesis, a DS is less effective in suppressing corporate rent-seeking among firms where the executive team has legal backgrounds. These findings suggest that top managers, especially within SOEs, should prioritize the early formulation of digital transformation strategies to reduce rent-seeking behavior. Additionally, when implementing digital transformation, firms should carefully integrate members with legal backgrounds into their executive teams and strengthen ethical education and supervision for executives with legal expertise.

1. Introduction

The abuse of authority and consequent corporate bribery and rent-seeking have long posed critical challenges for the international community, particularly in transitional economies like China’s [1,2]. Corporate rent-seeking involves manipulating public policies or economic conditions to secure advantages, with the goal of increasing profits [3]. There are many corporate rent-seeking activities, including corporate political lobbying, political contributions, or other forms of political participation, such as voluntary donations, active influence through their networks, and information [4]. Rent-seeking behavior manifests primarily as a political expenditure activity that requires management costs [5]. Therefore, this paper focuses on the rent-seeking behaviors that are most likely to generate excess overhead.

At a macrolevel, corporate rent-seeking disrupts the normal functioning of markets, economies, and societies. First, rent-seeking often supplants market mechanisms with political decisions, distorting market competition [6]. This distortion may lead to increased barriers to market entry and the formation of monopolies or oligopolies, and it may prevent new competitors from entering the market. Second, since rent-seeking activities typically involve securing government-provided privileges or concessions, they can redirect resources from productive to unproductive sectors. This diversion impedes the efficient allocation of resources, ultimately diminishing economic efficiency and growth potential [7]. Third, corporate rent-seeking may exacerbate social inequality, as it tends to be successfully executed only by large or wealthy entities with the resources and capabilities to influence political processes [2]. On a microlevel, many studies have demonstrated that corporate rent-seeking directly harms firms’ operations and performance. For instance, rent-seeking within firms negatively impacts corporate management practices and leads to a decline in overall productivity [8]. Rent-seeking within Chinese energy firms significantly inhibits technological progress [9], while rent-seeking in bank credit hampers firms’ research and development (R&D) innovations [10].

Following the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, a comprehensive anti-corruption campaign has been launched across the country. Throughout this campaign, numerous government officials and corporate executives have been investigated and punished, thus curtailing corporate rent-seeking behavior to a significant extent [11]. However, because rent-seeking is essentially invisible [12], it is imperative to not only audit and restrain such behaviors through state coercion but also to explore alternative methods, particularly through the management practices of enterprises themselves. With the rise of the digital economy, many enterprises have implemented a digitalization strategy, extensively integrating digital technology into their production and operations [13,14]. Digitalization strategy not only reshapes firms’ operational models but also offers new opportunities to strengthen their ethical codes and governance structures [15]. This strategy potentially provides firms with effective means to curb rent-seeking by enhancing the transparency and regulatory efficiency of their operations. For example, blockchain technology can provide transparent, tamper-proof records, while big data and artificial intelligence can monitor and alert firms to unusual behavior, significantly reducing opportunities for corruption or rent-seeking [16,17]. However, the relationship between a digitalization strategy and rent-seeking behavior remains largely unexplored. Therefore, this study aims to investigate two key issues within the digital economy environment, aiming to offer effective strategies for reducing unfair competition among firms and upholding a proper market order: (1) Does a firm’s digitalization strategy mitigate its rent-seeking? (2) Under what circumstances do the effects of a digitalization strategy on corporate rent-seeking vary?

To answer these two questions, we explore the relationship between corporate digitalization strategy and rent-seeking behavior based on resource dependence theory and agency theory. On the one hand, resource dependence theory suggests that resources that are needed by one organization may be in the hands of other organizations [18]. Organizations often resort to political strategies to create more favorable environments and use these strategies to change external economic conditions [18]. Meznar and Nigh (1995) [19] and Birnbaum (1985) [20] suggest that the more dependent a firm or manager is on the resources of a governmental or regulatory agency, the more likely they are to engage in political activities. Of course, in order to reduce environmental certainty and dependence, firms often resort to various means to increase their control over important resources [21], for example, prioritizing the appointment of directors with well-developed social networks [22]. In addition, we argue that implementing a digitalization strategy also potentially diminishes reliance on governmental information, policies, and economic resources, which in turn inhibits firms’ rent-seeking. On the other hand, agency theory suggests that the principal (investor) grants the agent (manager) certain decision-making powers to act on behalf of the principal [23]. Information asymmetry occurs when information is held privately, concealed, or strategically disclosed by managers to influence decisions or transaction outcomes [24]. Firm managers may manipulate operational and decision-making information to increase their own pay or achieve other gains, pursue unilateral expansion in scale, overinvest, and engage in excessive on-the-job spending, thus fostering corruption or rent-seeking [25,26]. The rent-seeking behavior of firms is more obvious when the internal monitoring and control mechanisms or means are not perfect [27]. We posit that the implementation of a corporate digitalization strategy will further attenuate the asymmetry of information, which in turn suppresses corporate rent-seeking.

We consider that the two theoretical explanatory mechanisms presented above will vary depending on the nature of enterprise ownership and the legal background of its executives. The nature of enterprise ownership influences firms in terms of their organizational design, decision-making processes, and resource allocation and utilization [28], thus potentially affecting the implementation of firms’ digital strategies. Research suggests that the nature of corporate property rights plays a role in the impact of digital orientation on organizational resilience [14]. In addition, corporate rent-seeking behavior typically occurs among corporate executives, and the executives’ characteristics influence their mindset and potential behavior [29]. Since corporate rent-seeking by executives violates corporate law, we argue that executive teams with legal backgrounds could potentially influence the impact of a digitalization strategy on corporate rent-seeking. Therefore, we consider the nature of enterprise ownership and the legal background of their executives to be two contingent roles. We tested our hypotheses using a fixed-effects model with relevant data from Chinese A-share firms listed between 2004 and 2021.

The primary contributions of this study are as follows: Firstly, it examines the impact of digitalization strategy on firms’ rent-seeking. Utilizing sample data from Chinese firms and employing a fixed-effects model, our empirical findings reveal that a digitalization strategy significantly and negatively impacts corporate rent-seeking. This discovery introduces a fresh perspective on understanding the factors influencing corporate rent-seeking and provides theoretical support and a methodological foundation for curtailing such behavior. Secondly, this study broadens the scope of research on the outcomes of digitalization strategies. It reveals that digitization not only affects corporate financial and innovation performance, as established by previous research, but also affects corporate ethics governance, specifically by mitigating corporate rent-seeking. Thus, this study enriches the literature on corporate digitization and strategic management. Thirdly, this study investigates the contingent conditions under which a digitalization strategy influences corporate rent-seeking. The findings suggest that the impact of a digitalization strategy on corporate rent-seeking varies depending on the nature of enterprise ownership and the legal background of its executives. Lastly, this study provides several insights for managers and governments. Given China’s status as one of the world’s largest digital economies, these insights not only inform the digital transformation strategies of firms in other countries but also offer valuable guidance for government policymakers on supporting firms in addressing rent-seeking behaviors.

The following sections of the study are structured as follows: First, we conduct a review of prior studies relating to corporate rent-seeking and digitalization strategy, developing our hypotheses, which are grounded in agency theory and resource dependence theory. Second, we test our hypotheses using the panel data from Chinese A-share listed companies. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of our findings and propose directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Corporate Rent-Seeking

Rent-seeking is broadly defined as an activity aimed at obtaining a monopoly position, usually through non-competitive means of obtaining government favors [30]. Corporate rent-seeking (CRS) involves firms making efforts to influence and manipulate policymaking, legal frameworks, or economic conditions to acquire additional benefits or advantages without engaging in market competition [3,31]. For instance, firms may attempt to sway legislators and policymakers through lobbying activities, political contributions, or other forms of political engagement, such as voluntary donations, active participation in political processes, and influencing through their information, networks, and/or voting [4]. These actions facilitate access to favorable policies, regulations, concessions, subsidies, regulatory privileges, or other forms of assistance [3].

Upon reviewing previous studies on corporate rent-seeking (see Table 1), we observed that prior research predominantly concentrated on its external influences while overlooking the study of internal corporate factors. Emphasis has been placed on aspects such as religious traditions [2], officials’ Chinese vernacular culture [32], government subsidies [33], and perfect checks [34]. Although Ciabuschi et al. (2012) [1] suggest that a technology transfer capability grants subsidiaries greater bargaining power, consequently fostering rent-seeking behavior, and Lin and Xie (2023) [33] demonstrate that the social network of the board of directors effectively suppresses managerial rent-seeking, these studies ignore the role of relevant contingent factors. To our knowledge, existing research has not specifically investigated the influence of corporate strategic factors on corporate rent-seeking behavior. Therefore, this study aims to explore the effects of corporate digitalization strategy on corporate rent-seeking behavior while also considering the relevant situational conditions. In doing so, we aim to address the identified gaps in prior research.

Table 1.

Comparison of this study with extant literature focusing on antecedents of rent-seeking.

2.2. Digitalization Strategy

A digitalization strategy (DS) refers to a set of practices whereby an organization commits to integrating information and digital technologies across all aspects, encompassing not only overall and functional strategy development but also management systems, business processes, and activities that are external to the organization [13,35]. A DS transcends the mere digitization of organizational resources; it leverages the infrastructure of digital technologies, products, and platforms as foundational supports, triggering comprehensive organizational changes in an organization’s processes, structures, and cultures, and even business model transformations [36,37,38,39]. This strategy focuses on the use of technology, the enhancement of value creation capabilities, the transformation of organizational structures, and the capture of economic gains [40].

Current research on DS primarily focuses on its antecedents and impacts. For example, a DS has been found to positively influence firms’ economic [41,42,43], innovative [37], and social performance [44]; Begnini et al. (2023) [45] demonstrated that a DS positively affects the use of technology; Nguyen et al. (2024) [35] identified three stakeholder factors (customer orientation, supplier collaboration, and employees’ IT skills) that positively contribute to fostering a big data organizational culture, thereby facilitating DS implementation; and Low and Bu (2021) [46] argued that internal corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices positively impact employees’ organizational commitment, while a DS mediates the relationship between internal CSR practices and affective commitment.

Previous studies underscore the substantial contribution of DS to enhancing the economic, innovative, and social performance of organizations. However, they frequently overlook their influence on corporate rent-seeking. This research gap neglects the potential of DSs to promote ethical corporate behavior and enhance the quality of corporate governance, particularly in addressing rent-seeking behavior. Therefore, a comprehensive examination of how DS influences corporate rent-seeking can furnish companies with strategies to mitigate ethical risks and bolster self-regulation. Furthermore, such research represents a significant step forward in advancing CSR practices and fostering the development of healthy corporate ecosystems.

2.3. Digitalization Strategy and Corporate Rent-Seeking

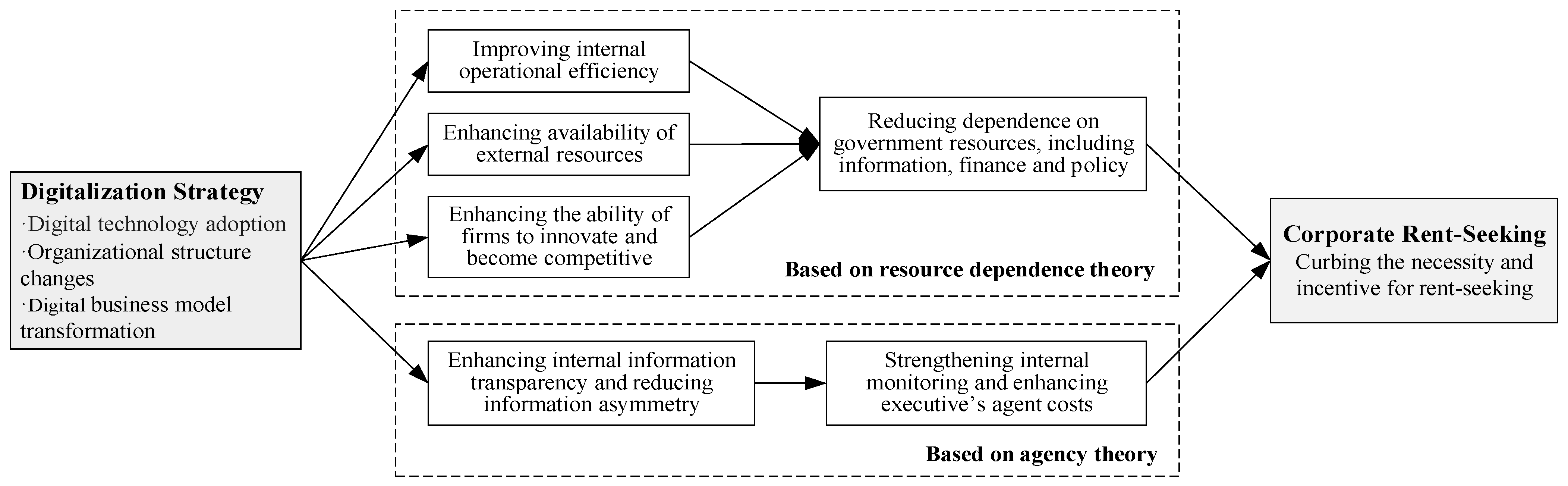

We mainly developed our hypotheses based on resource dependence theory and agency theory. The logic of our main hypothesis is shown in Figure 1. According to resource dependence theory, organizations depend on resources originating from their environment, some of which may be controlled by other organizations [18]. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) [18] assert that organizations strive to create a more favorable environment through political strategies, utilizing these strategies to influence external economic factors. Research conducted by Meznar and Nigh (1995) [19] and Birnbaum (1985) [20] indicates that the higher the dependence of firms or managers on government or regulatory agencies, the more likely they are to engage in political activities, thereby increasing the propensity for rent-seeking behavior. To mitigate the reliance on critical external resources, firms employ various strategies to secure stable access to resources, thereby enhancing their autonomy and mitigating the impact of external uncertainties [21]. For example, corporate boards often prioritize the appointment of directors with extensive social networks, as these directors can access broader and more timely private information, effectively mitigating managerial rent-seeking [22]. In addition, certain strategic initiatives undertaken by firms, such as digitalization strategies, can also impede rent-seeking by diminishing the reliance on governmental information, policies, and economic resources, as explained below:

Figure 1.

Logical framework of the main hypothesis.

First, a DS enhances internal operational efficiency. Highly digitalized firms not only optimize supply chain management processes like inventory, procurement, and production scheduling through technological means such as big data analysis [47,48], they are also assisted with accurately identifying and satisfying customer needs and market preferences [14,49]. By refining support systems for decision-making and effectively allocating internal resources [50], a DS strengthens the company’s ability to sustain itself, reducing its dependence on specific external resources—including those provided by governments—thereby diminishing incentives for and the necessity of rent-seeking. Second, a DS enhances the availability of external resources. The use of digital platforms facilitates the exchange of information between the organization and external stakeholders, strengthens collaboration among partners, and facilitates the integration and sharing of resources, thereby promoting value creation among stakeholders [39,51,52]. As firms identify and access relevant customer- and partner-related resources, they become more self-reliant and less reliant on the government, thereby inhibiting rent-seeking behaviors. Third, a DS assists firms in enhancing their capacity to innovate and become more competitive in the market. Firms with greater digital maturity are more adept at leveraging technology for innovation, improving the quality of services or products, and reducing costs, thereby establishing a competitive edge in the market [37,53]. This ability to gain a competitive advantage through legitimate means diminishes the necessity for organizations to rely on governmental interventions such as tariff protections or market access restrictions to secure their market position, as they can depend on their own innovation and efficiency for success.

In addition, according to agency theory, managers (agents) and investors (principals) establish a contractual relationship wherein the principal delegates decision-making authority to the agent [23]. Information asymmetry occurs when information is privately held, concealed, or strategically disclosed by managers to influence decisions or transaction outcomes [24]. Managers may manipulate operational and decision-making information to increase their compensation or other benefits, pursue unilateral expansion in scale, overinvest, and engage in excessive on-the-job spending, thus fostering corruption or rent-seeking [25,26]. This study contends that the digital operations initiated by the digitalization strategy within firms serve as a new means to govern corporate rent-seeking. A DS enhances information transparency within the firm, mitigating information asymmetry [51]. The incorporation of digital technologies, such as big data, enhances the visualization of business processes and the traceability of data [47]. Additionally, the adoption of blockchain and artificial intelligence technologies in accounting and audit management systems improves the quality and transparency of accounting information, thereby reducing information asymmetry [25,54]. Internal control systems are more effective when information within firms is more transparent [55]. Specifically, this transparency facilitates bottom-up monitoring or whistleblowing [56]. In such an environment, critical information concerning a firm’s financial flows and contract execution becomes more transparent to external stakeholders, including government regulators, investors, and the public. This transparency diminishes the scope and potential for corporate executives to seek undue advantages. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Corporate digitalization strategy has a significant negative impact on rent-seeking behavior.

2.4. The Contingent Effect of the Nature of Enterprise Ownership

We contend that the inhibitory effect of digitization strategy on corporate rent-seeking is more pronounced in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) than in non-SOEs. Firstly, owing to their political and public attributes, SOEs are subject to more rigorous governmental and public scrutiny [57,58]. For example, SOEs consciously strengthen anti-corruption initiatives [59]. As a result, SOEs incur higher rent-seeking costs than non-SOEs do [32]. A corporate digitization strategy facilitates the adoption of artificial intelligence and blockchain management systems to enhance the transparency and traceability of SOEs’ accounting and auditing [25,60], thereby further exposing SOEs to rent-seeking behavior. Secondly, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) exhibit greater sensitivity to governments’ digital policies, which are directly or indirectly affected by regulations and financial support, which accelerates the maturation of DSs [61]. Therefore, DSs can effectively inhibit rent-seeking behavior in SOEs. Thirdly, SOEs rely heavily on government channels for resource acquisition, notably in financing and market access [62,63]. Digital technologies have empowered these enterprises to enhance their resource acquisition, management, and utilization efficiency, reducing their dependence on special government favors or interventions and thereby reducing the incentives and likelihood of engaging in rent-seeking behavior.

In contrast, non-state-owned firms are not as constrained by governmental or bureaucratic influence and rely more on market competition for resources [64]. Even without access to government subsidies for digital transformation, these firms continue to pursue enhanced competitiveness, market development, and innovation through DSs. Therefore, their inclination to seek rent from the government may not necessarily increase or decrease. Additionally, non-state-owned enterprises (NSOEs) may sometimes find it necessary to maintain political connections with the government to access legitimate resources, potentially resulting in less stringent monitoring of corporate rent-seeking behavior despite increased digitalization. As a result, the direct disincentive effect of digitalization on rent-seeking behaviors in non-state-owned firms may not be as significant as it is in state-owned firms. Therefore, we propose the following:

H2.

In comparison to non-state-owned firms, digitalization strategy is more effective in curbing corporate rent-seeking within state-owned firms.

2.5. The Contingent Effect of Executives’ Legal Background

In addition to considering the nature of enterprises’ ownership, we argue that the inhibitory effect of DS on corporate rent-seeking also varies depending on the legal backgrounds of the executives, as the executives’ legal backgrounds shape their decision-making patterns and styles. First, executives with legal professional backgrounds are educated in legal principles, making them more aware of and compliant with the law [65]. They are inclined to implement policies that not only reduce future risks to the firm but also enhance the transparency of reporting and reduce information asymmetry, thereby bolstering credibility [66]. Consequently, they are more likely to understand and promote the adoption of digital technologies to strengthen internal controls and the transparency of processes. This approach increases agency costs for executives and ultimately reduces the opportunities for improper transactions and rent-seeking behaviors within and outside the firm.

Second, executive team members with a legal background typically hold expertise in patent law and possess knowledge about intellectual asset protection [67,68]. As a result, they are more inclined to utilize digitalization to enhance their firms’ patenting activities and maintenance. In the contemporary digital landscape, data security and privacy protection pose significant challenges for businesses [69]. Executives with legal backgrounds play a pivotal role in steering firms towards adopting robust data protection measures, thereby fostering trust among consumers and partners and facilitating access to additional resources for development. Within this framework, a DS further amplifies firms’ innovation performance and market competitiveness, consequently diminishing their reliance on governmental innovation policies.

Third, executive team members with legal expertise typically cultivate extensive external networks over their careers, forging connections with peers, customers, and other key stakeholders [70,71]. These networks empower executives with legal acumen to gain access to vital information, financial backing, and other forms of support for their firms. Collaboration and knowledge sharing among individuals, companies, and organizations play a crucial role in enhancing firms’ digital innovation capabilities through DS [72]. Ultimately, this reduces the reliance on direct government support and the necessity for rent-seeking to some extent. Therefore, we propose the following:

H3.

Digitalization strategy is more likely to inhibit rent-seeking in firms with legal executives than in firms without legal executives.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Sample and Data Sources

Our sample is derived from all A-share companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges in China from 2004 to 2021. The data primarily originate from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. This database provides general information on firms’ background and financial statistics, as well as their executives’ demographics. It is widely used by scholars in the field of economic and management research [7,73]. After excluding delisted companies, those with missing data, and those from the financial sector, we winsorized continuous variables at 1% and 99%, resulting in a total of 31,795 observations across 3879 companies.

3.2. Variable Measurement and Model Setting

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

Current measurements of corporate rent-seeking are based on two approaches: questionnaire data [1,4] and financial reporting analyses [32,74]. However, questionnaire data are criticized for their limitations and potential inaccuracies due to the firms’ reluctance to disclose rent-seeking activities [32,75]. Consequently, this study adopts the reporting analysis approach, following the methodologies outlined by Chen et al. (2021) and Liu et al. (2018) [3,31] for measuring corporate rent-seeking (see Equation (1) below), which was also used in previous research [7]. The main advantages of this method include the use of data from audited accounting reports and the relative completeness of such data [32]. By relying on such data, this study seeks to provide a more accurate understanding of corporate rent-seeking behaviors and their implications.

Mgtexpi,t = β0 + β1ln Salei,t + β2Levi,t + β3Growthi,t + β4Boardi,t + β5Staffi,t +

β6Big4i,t + β7Agei,t + β8Magini,t + β9Herfindahl_5i,t + ∑Industryi,t + ∑Yearit + εi,t

β6Big4i,t + β7Agei,t + β8Magini,t + β9Herfindahl_5i,t + ∑Industryi,t + ∑Yearit + εi,t

In Equation (1), the variable subscript i denotes the company; t represents time; Mgtexp is the overhead divided by the operating income in the same period; LnSale is the natural logarithm of the firm’s operating income; Lev is the gearing ratio; Growth denotes the growth rate of the firm’s operating income; Borad is the size of the company’s board of directors; Staff indicates the total number of employees in the firm; Big4 is the type of accounting firm (1 if it is an international Big 4 accounting firm and 0 otherwise); Age is the number of years the company has been listed; Magin is the firm’s gross profit margin; and Herfindahl_5 is the Herfindahl index of the firm’s top five shareholders, which measures the equity concentration. The continuous variables in the above model are Winsorized to shrink the tails based on the quartiles of 1% and 99%. The residual term obtained from the regression represents the excess administrative expenses, recorded as Rent, which serves as a proxy variable for the degree of corporate rent-seeking.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

We assess the maturity of a firm’s digitalization strategy based on its digital investments. Digital investments refer to a firm’s capital allocation to advanced technologies, products, services, and solutions guided by DS principles, aiming to optimize the management of digital assets both internally and externally [76]. We refer to Zhang et al. (2021) [77] and Liu et al. (2023) [78] for methods for measuring digital transformation. The extent of a firm’s DS is quantified by calculating the proportion of the year-end intangible assets related to digital transformation to the total intangible assets, as disclosed in the financial statement notes of listed companies. An intangible asset is categorized as an “intangible digital technology asset” if its financial disclosure description includes keywords related to digital transformation technologies such as “software”, “network”, “client”, “management system”, “intelligent platform”, and related patents. The total of these intangible digital technology assets for a given firm in a given year is aggregated to determine the proportion of digital intangible assets for that year. This proportion serves as a proxy variable for how developed the firm’s DS is. To ensure the accuracy of the screening, we also conduct manual reviews of the categorized items.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Drawing on the existing literature [2,26,73,79], we consider a number of variables that may affect corporate rent-seeking, consisting of three financial variables of a firm: return on assets (ROA), financial leverage (Lev), and revenue growth (Growth); we also consider six board and management variables—board size (Board), independent board (IndepBoard), top one (Top1), management shareholding (Mshare), and dual title (Dual)—as well as two variables for other aspects of the firm—size (Size) and age (Age)—as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variable measurements.

3.2.4. Model Setting

The results of our Hausman test indicate the rejection of the original hypothesis in favor of a fixed-effects model. Opting for a fixed-effects model offers the advantage of mitigating bias stemming from endogeneity issues [80]. Therefore, this paper establishes the following benchmark regression model to assess the research hypotheses presented earlier:

where the dependent variable Rent represents the firm’s rent-seeking behavior. The core explanatory variable DS represents a firm’s digitalization strategy. Control represents each control variable; Industry, Year, and Firm denote the fixed effects of the industry, year, and firm, respectively; and ε represents the random error term.

Renti,t+1 = β0 + β1 DSi,t + β2 Controli,t + ∑Industryi,t + ∑Yeari,t + ∑Firmi,t + εi,t

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Upon examining the descriptive statistics in Table 3, it is observed that the mean value of rent-seeking is −0.002, with a maximum value of 0.176. The mean value of the corporate digitalization strategy is 0.090, with a maximum value of 1.000. The descriptive results of the other variables align closely with existing studies [26,73]. Furthermore, from Table 4, it can be noted that the Pearson correlation coefficients between our variables all fall below |0.48|. Rent is negatively correlated with DS, providing a valid basis for the initial hypothesis. In addition, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of all variables are less than 2.50, and the average VIF value is 1.35, suggesting the absence of multicollinearity problems within the main model.

Table 3.

Variable descriptions.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of variables.

4.2. Results of Basic Regression Analyses

The results of our regression analysis are presented in Table 5. It demonstrates that in Model 1 (β = −0.005, p < 0.01), digitalization strategy has a significant negative impact on corporate rent-seeking. This finding strongly aligns with Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Table 5.

Results of digitalization strategy in firms on rent-seeking.

4.3. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

Possible endogeneity problems in finance-dependent regression models mainly include reverse causation, omitted variable bias, and measurement error, which may affect the robustness of the study results. To address these issues, various remedial strategies are discussed.

First, while we initially lagged the dependent variable by one period to alleviate endogeneity issues, we took additional steps to address reverse causality by employing the instrumental variable method. The instrumental variable approach can solve many endogeneity problems, such as reverse causation, omitted variables, and independent variable errors [81,82]. Drawing from existing research, we utilized the mean value of digitalization within the same industry but across different firms as an instrumental variable [83]. Additionally, we incorporated the number of post offices per million people at the end of 1984 for 283 prefecture-level cities in China as another instrumental variable. This metric has previously been employed in studies to assess the level of digital economy development in cities [84]. The two variables are closely related to the firm’s digitalization without having an impact on the firm’s rent-seeking behavior. We conducted a two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression involving these two instrumental variables. The results are presented in Model 2 (β = −0.051; p < 0.05) and Model 3 (β = −0.203; p < 0.1), respectively. These findings indicate that a DS significantly and negatively impacts corporate rent-seeking.

Second, this study employs the total digital intangible assets as a proxy for the independent variable. The regression analysis in Model 4 (β = −0.000; p < 0.1) indicates a significant reduction in corporate rent-seeking due to DS. Third, this study substitutes the measure of the dependent variable. Following the methodologies of Du et al. (2010) [74], Fu and Wu (2018) [32], and Zhang et al. (2023) [26], we calculated the excess overhead as the difference between the actual and expected overhead, estimating the latter by using the model. The results from Regression Model 5 (β = −0.004; p < 0.01) confirm that a DS continues to significantly suppress corporate rent-seeking. The latter two approaches provide a better test of the measurement error of the variables.

Fourth, we used the propensity score matching (PSM) method to test the issue of sample selection bias [85]. Specifically, we based this on the 1:1 closest match principle [86]. As shown in Table 6, the results of the matched fixed-effects model in Model 6 (β = −0.007; p < 0.01) remain consistent with the initial results.

Table 6.

Results of alternative endogeneity and robustness tests.

Fifth, we added two firm variables (book-to-market ratio and auditing quality based on Big 4 auditors) and three variables describing CEO characteristics (age, gender, financial background) to address potential omitted variables. The results of Model 7, which models the main effects (β = −0.004; p < 0.01), are consistent with our previous ones.

Sixth, we added two discussions about the sensitivity analysis of the results: (1) In our fixed-effects model, robust regressions were conducted in Stata version 17 software to correct for coefficient standard errors. This has the advantage of excluding potential heteroskedasticity in the regression model. The results are shown in Model 8 (β = −0.005; p < 0.1). (2) Since the years 2020 and 2021 are in the “pandemic period” and the digital activities of organizations may be affected by this [87], we excluded the samples from these two years, and the results show that digitalization still has a significant negative impact on corporate rent-seeking in Model 9 (β = −0.004; p < 0.01).

Seventh, we replaced four measures of firm size to address measurement errors. Research points out that there are multiple ways to measure a firm’s size, and a single measure may not ensure the robustness of the results [88]. We replaced the measure of the natural logarithm of total assets with the natural logarithm of total sales, market value of equity, net worth, and total number of employees, respectively. The regression results for Model 10a–Model 10d in Table 7 remain consistent with the previous ones. The measure of firm size in this study is based on the majority of previous studies on corporate rent-seeking [26,73,79]. In summary, H1 is strongly supported.

Table 7.

Results of measurement methods for different firm sizes.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

We conducted subgroup regressions to assess the impact of digitalization strategies on firms’ rent-seeking according to whether they are SOEs or have executives with legal backgrounds (see Table 8). The results of Models 11 and 12 reveal that a digitalization strategy has a more significant dampening effect on SOEs’ rent-seeking (βstate-owned firms = −0.009, p < 0.01; βnon-state-owned firms = 0.001, p > 0.1), thus confirming Hypothesis 2. However, contrary to our hypothesis, the results from Model 13 (firms without executives with legal backgrounds) demonstrate that the digitalization strategy is more inhibitory to corporate rent-seeking behavior compared with Model 14 (firms with executives with legal backgrounds) (βlegal background firms = −0.001, p > 0.1; βnon-legal background firms = −0.009, p < 0.01). Consistent findings were obtained upon altering the dependent variable measure (refer to Table 9). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Table 8.

Results of grouping regression analysis.

Table 9.

Results of grouping regression analysis (robust tests).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

Currently, corporate rent-seeking is an extremely important topic in the fields of corporate governance and business ethics. With the rise of the digital economy, an increasing number of firms are choosing to implement digital strategies. This study tests the impact of corporate digital strategies on rent-seeking by utilizing a dataset of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2021. Our findings suggest that a corporate DS has a significant negative influence on rent-seeking. Several robustness tests support this conclusion. Moreover, our analysis indicates that a DS is particularly effective in curtailing rent-seeking behaviors within state-owned enterprises (SOEs) compared with their non-state-owned counterparts. However, contrary to our hypothesis, a DS is less effective in suppressing corporate rent-seeking among firms with a legal background in the executive team. This could be attributed to two reasons:

On the one hand, executives with legal backgrounds often demonstrate a conservative approach and a heightened aversion to risk [89]. For instance, when confronted with new opportunities for growth in research and development (R&D) or innovation, they may choose to maintain the status quo [90]. Research indicates that CEOs with legal expertise tend to allocate fewer resources to R&D initiatives [91] and are more sensitive to the risks associated with litigation [91]. However, the implementation of a DS inherently involves substantial risk, necessitating continuous investments in digital technologies to integrate them into existing business processes and models. It is important to note that firms may not realize the anticipated benefits of digitalization in the short term, and there is a possibility of encountering challenges that result in what has been termed a “digital trap” [92,93,94]. Furthermore, digital transformation frequently renders organizations vulnerable to legal action from customers or other stakeholders concerning data security and privacy matters [95]. Consequently, executives with legal backgrounds may be reluctant to pursue digital strategies aimed at enhancing operational efficiencies, leveraging external development resources, and bolstering market competitiveness. Instead, they may be inclined to engage in rent-seeking behaviors to acquire information and resources from governmental sources.

On the other hand, executives with legal training often excel at providing technical guidance for interpreting the law, helping companies navigate legal sanctions and regulations through methods such as knowingly exploiting legal loopholes [65]. They are more concerned with safeguarding individuals’ private information and transactional activities. Consequently, such executives may be hesitant to adopt advanced technologies like AI or blockchain within their firms, fearing the potential exposure to unethical practices. Consequently, this apprehension undermines corporate information transparency and creates avenues for rent-seeking behaviors. Moreover, research indicates that executives who have previously served as general counsels may inadvertently lead their firms towards engaging in risky behaviors that push the boundaries of legality, thereby heightening corporate credit risk [96]. Once stakeholders lose trust in the firm, accessing resources from partners to support digital innovation [97] and enhancing open innovation capabilities [98] becomes increasingly challenging. In such circumstances, the firm may find itself more incentivized to seek governmental endorsements or resort to rent-seeking practices to obtain essential support.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several significant theoretical contributions. Firstly, it extends research on the antecedents of corporate rent-seeking. While previous studies have predominantly focused on the outcomes of corporate rent-seeking, they have often overlooked its antecedents. For instance, Chen et al. (2021) [31] identified that firms with higher levels of rent-seeking tend to procure audit opinions; Du et al. (2021) [99] argued that the rent-seeking behavior of local firms significantly undermines the enforcement of environmental regulations; and Liu et al. (2018) [3] observed that corporate rent-seeking contributes to increased surplus management. Furthermore, corporate rent-seeking reduces a firm’s profitability, thus inducing outward foreign direct investment [7]. However, few studies have examined intra-firm factors, particularly concerning corporate strategy, in the context of corporate rent-seeking. Previous research has primarily examined the influence of external environmental factors on corporate rent-seeking, such as religious traditions [2], officials’ Chinese vernacular culture [32], and government subsidies [33]. Secondly, this study contributes to the literature on the outcomes of DS. Prior studies on DS have predominantly focused on their effects on firms’ financial [41,43], innovation [43], and environmental, social, and governance performance [44]. However, these studies have neglected to explore the impact of DS on corporate ethics governance. Thirdly, prior studies have overlooked the contingent conditions affecting the impact of constructs on corporate rent-seeking. According to contingency theory, there are no universally applicable principles or methods in every managerial scenario; outcomes invariably hinge on aligning organizational characteristics with these principles to yield superior performance [100]. This study posits that the impact of DS on corporate rent-seeking varies depending on the nature of corporate ownership and the legal background of corporate executives. Specifically, it demonstrates that, compared with non-state-owned firms, a DS is more effective in curbing corporate rent-seeking in state-owned firms. Moreover, a DS is more likely to inhibit rent-seeking behavior in firms without legal executives than in those with legal executives.

5.3. Management Implications

Based on the results of this study, several managerial insights emerge for business leaders and policymakers. First, a well-defined digitalization strategy can serve as a roadmap for management to steer corporate transformation through the integration and utilization of digital technologies. Hence, formulating a precise strategy for the deployment and application of these technologies is paramount for the future success of enterprises. Confronted with the challenges and prospects of the digital economy era, organizations must explore effective ways of leveraging digital strategies to modernize corporate governance and foster a more transparent, efficient, and equitable business environment. Managers should develop systematic procedures for implementing DSs, coordinating the administrative, production, operational, financial, and marketing departments of the company to progressively achieve digitalization. While this journey presents numerous challenges, it also presents unprecedented opportunities for mitigating corruption and rent-seeking behaviors.

Second, for state-owned enterprises, the application of digitalization in governing rent-seeking should be strengthened. Specific recommendations include the following: (1) The construction of digital platforms by state-owned enterprises to amalgamate data and resources should be prioritized. These enterprises should prioritize the development of middle-platform infrastructure for cloud computing and big data analytics, continually enhancing their capacity for data storage, analysis, and management to improve the transparency of operations and decision-making within state-owned enterprises. (2) In advancing the execution of digitalization strategies, state-owned enterprises should prioritize fostering an environment of transparency. This could involve establishing comprehensive regulations for information disclosure and cultivating a corporate culture that is supportive of this transparency. (3) Corporate financial regulatory departments should enhance the development of financial reporting systems utilizing new technologies like blockchain. They should clarify mandatory disclosure rules concerning business management expenses linked to corporate rent-seeking. Disclosing actions involving covert non-compliant behaviors can reduce the tendency of state-owned enterprise executives to manipulate accounting profits to conceal rent-seeking activities.

Third, when hiring executives with legal backgrounds, companies should undertake the following measures: (1) Strengthen educational and training initiatives. By enhancing the professional training and education of executives with legal backgrounds, companies can ensure that they fully understand the nature and value of digital transformation. In addition, encouraging them to abandon overly conservative behavior patterns due to concerns about legal risks will enable them to boldly implement digital transformation strategies. This approach can also enhance their self-discipline and ethical standards, thereby mitigating behaviors that exploit legal gray areas by using their legal knowledge. (2) Enhance supervision mechanisms. Given that executives with legal backgrounds may engage in more covert and challenging-to-detect rent-seeking behaviors, companies should employ digital tools to enhance the monitoring of these executives. For example, they should utilize data sharing and artificial intelligence technologies to track their potential rent-seeking behaviors. (3) Implement stricter punitive measures. Given that executives with legal backgrounds, if engaged in rent-seeking, are essentially knowingly committing the act, which is more egregious in nature, stricter punitive measures should be taken against them compared with executives without legal backgrounds. In the context of digital transformation, stricter disciplinary actions should be enforced against these executives.

Finally, the following recommendations for the government are proposed: (1) The government should encourage and support companies, especially state-owned enterprises, to enhance digital transformation efforts. This support should encompass not only daily operations but also regulatory and internal control mechanisms to improve transparency and efficiency. The government can facilitate this by offering financial subsidies, tax incentives, and technical training. (2) Optimize the role and training of executives with legal expertise. The government should develop specialized training and development programs to assist these executives in effectively leveraging digital tools in legal and compliance matters. This initiative should aim to enhance their sense of responsibility in promoting corporate ethics and legal compliance. (3) Strengthen digital regulatory capabilities. The government should enhance its capacity to regulate companies utilizing digital tools. Particular attention should be given to enhancing the monitoring efforts of high-risk enterprises and industries and employing digital methods for auditing and taxation to accurately pinpoint issues in corporate operations. Priority should be placed on intensifying the supervision of state-owned enterprises and establishing a comprehensive digital supervision mechanism to ensure transparency and control over the actions of state-owned enterprise executives throughout all processes.

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

This study has certain limitations that provide potential areas for future research. Primarily, the study utilizes panel data from companies listed on China’s A-share market, thereby rendering its conclusions predominantly relevant to the Chinese market. This aspect may limit the generalizability of the results, as different political, economic, and cultural contexts in other countries and regions could influence the effect of DS on corporate rent-seeking in different ways. Future research could expand to other countries and regions to examine the impact of digital strategies on corporate rent-seeking behaviors under different political and economic landscapes. This comparison might offer deeper insights into the dynamic relationship between digital policies and corporate behavior. Second, while this study indicates that the presence of executives with legal backgrounds in the executive team may weaken the effect of digital strategies on curbing rent-seeking, other contextual factors are also noteworthy. This could encompass factors such as the personal values of executives, industry-specific characteristics, or internal governance frameworks within companies. Future studies should undertake a more thorough examination of how executives with legal backgrounds shape a firm’s ethical and compliance decisions. Investigations could encompass considerations such as individual attributes, professional backgrounds, and their roles within the corporate hierarchy. Third, this study primarily focuses on the direct impact of digital strategies on corporate rent-seeking and may not fully consider other relevant variables, such as corporate culture, changes in the market environment, or the speed of technological development, all of which could influence the results. Future research could delve into how digital strategies interact with other corporate practices, like human resource management and innovation strategies, that collectively affect corporate rent-seeking. Fourth, our study cannot test what kind of digitization can mitigate what kind of rent-seeking; therefore, future research could use case studies, qualitative interviews, or experimental designs to explore the impact of specific digitization processes on specific firms’ rent-seeking behaviors, which could deepen our understanding of the operation and effectiveness of digital strategies in different contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and Y.L.; methodology, X.Y. and Y.L.; software, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, X.Y.; resources, X.Y.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.L.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ciabuschi, F.; Dellestrand, H.; Kappen, P. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Technology transfer competence, rent-seeking, and bargaining power. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Fan, Y.; Liang, S.; Li, M. The power of belief: Religious traditions and rent-seeking of polluting enterprises in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 54, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lin, Y.; Chan, K.C.; Fung, H.-G. The dark side of rent-seeking: The impact of rent-seeking on earnings management. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, J. State-controlled economies vs. rent-seeking states: Why small and medium enterprises might support state officials. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.A. Lobbying and political expenses: Complements or substitutes? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsira, M.; Denkers, A.; Huisman, W. Both Sides of the Coin: Motives for Corruption Among Public Officials and Business Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Li, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X. How corporate rent-seeking affects outward FDI—Empirical evidence based on A-share listed manufacturing companies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasouli, D.; Goujard, A. Corruption and management practices: Firm level evidence. J. Comp. Econ. 2015, 43, 1014–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, M.; Wang, F. Role of rent-seeking or technological progress in maintaining the monopoly power of energy enterprises: An empirical analysis based on micro-data from China. Energy 2020, 202, 117763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.T. Rent-seeking in bank credit and firm R&D innovation: The role of industrial agglomeration. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 159, 113454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Huang, J.; Ma, G. Anti-corruption and within-firm pay gap: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2023, 79, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, O. The visual politics of corruption. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 2129–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Yan, T.; Dai, W.; Feng, J. Disentangling the interactions within and between servitization and digitalization strategies: A service-dominant logic. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 238, 108175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Han, Z.; Gavurova, B.; Bresciani, S.; Wang, T. Effects of digital orientation on organizational resilience: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 35, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Shilton, K.; Smith, J. Business and the Ethical Implications of Technology: Introduction to the Symposium. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Evolutionary game analysis of rent seeking in inventory financing based on blockchain technology. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 4278–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trequattrini, R.; Palmaccio, M.; Turco, M.; Manzari, A. The contribution of blockchain technologies to anti-corruption practices: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 33, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Meznar, M.B.; Nigh, D. Buffer or Bridge? Environmental and Organizational Determinants of Public Affairs Activities in American Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, P.H. Political Strategies of Regulated Organizations as Functions of Context and Fear. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource Dependence Theory: A Review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Rao, X.; Zhang, W. Social networks and managerial rent-seeking: Evidence from executive trading profitability. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2024, 30, 602–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. In Economic Analysis of the Law; Wittman, D.A., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M. How far can we trust earnings numbers? What research tells us about earnings management. Account. Bus. Res. 2013, 43, 445–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shiwakoti, R.K.; Jarvis, R.; Mordi, C.; Botchie, D. Accounting and auditing with blockchain technology and artificial Intelligence: A literature review. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2023, 48, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Niu, F.; Su, W. Association Between State Ownership Participation and Rent-Seeking Behavior of Private Firms in China. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2024, 69, 81–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.Q.; Vu, T.P.L.; Do, V.P.A.; Do, A.D. The enduring effect of formalization on firm-level corruption in Vietnam: The mediating role of internal control. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 82, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, J.L.; Banister, D. Resources, state ownership and innovation capability: Evidence from Chinese automakers. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Geletkanycz, M.A.; Sanders, W.G. Upper Echelons Research Revisited: Antecedents, Elements, and Consequences of Top Management Team Composition. J. Manag. 2016, 30, 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatright, J.R. Rent Seeking in a Market with Morality: Solving a Puzzle About Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Lin, J. How Does Enterprise Rent-seeking Affect Audit Opinion Shopping? Account. Res. 2021, 7, 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Wu, F. Culture and Enterprise Rent-Seeking: Evidence from Native Place Networks among Officials in China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trad. 2018, 55, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Xie, J. Superior administration’s environmental inspections and local polluters’ rent seeking: A perspective of multilevel principal–Agent relationships. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ni, H.; Yang, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, C. Government subsidies and total factor productivity of enterprises: A life cycle perspective. Econ. Polit. 2023, 40, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Dang-Van, T.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Do, H.-N.; Pervan, S. Digitalization strategy adoption: The roles of key stakeholders, big data organizational culture, and leader commitment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 117, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, L.; Han, C.; Gupta, B.; Alhalabi, W.; Almakdi, S. Exploring the effect of digital transformation on Firms’ innovation performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzaska, R.; Sulich, A.; Organa, M.; Niemczyk, J.; Jasiński, B. Digitalization Business Strategies in Energy Sector: Solving Problems with Uncertainty under Industry 4.0 Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Du, H. Enterprise digitalisation and financial performance: The moderating role of dynamic capability. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 35, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Benlian, A. Digital transformation strategies. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2015, 57, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Yang, M.; Chan, K.C. Does digital transformation enhance a firm’s performance? Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, M.; Dhir, S. Modeling the effects of digital transformation in Indian manufacturing industry. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.-T.; Chen, J.-S. How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 35, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Li, S. Analyzing the Relationship between Digital Transformation Strategy and ESG Performance in Large Manufacturing Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begnini, S.; Oro, I.M.; Tonial, G.; Dalbosco, I.B. The relationship between the use of technologies and digitalization strategies for digital transformation in family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.P.; Bu, M. Examining the impetus for internal CSR Practices with digitalization strategy in the service industry during COVID-19 pandemic. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 31, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.J.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Linkage between digital supply chain, supply chain innovation and supply chain dynamic capabilities: An empirical study. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, E.; Ball, P. Applying digital twins for inventory and cash management in supply chains under physical and financial disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 5094–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H.; Zhan, Y.; Ji, G.; Ye, F.; Chang, C. Harvesting big data to enhance supply chain innovation capabilities: An analytic infrastructure based on deduction graph. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 165, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Q. Digital transformation, external financing, and enterprise resource allocation efficiency. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 45, 2321–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppelletto, A.; Bullini Orlandi, L.; Rossignoli, C. Adopting a digital transformation strategy to enhance business network commons regeneration: An explorative case study. TQM J. 2020, 32, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonig, J.; Schmid, T.; Müller-Stewens, G. From product system to ecosystem: How firms adapt to provide an integrated value proposition. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 1927–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Benlian, A.; Matt, C.; Wiesböck, F. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Giang, N.P.; Tam, H.T. Impacts of Blockchain on Accounting in the Business. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, M.; Tian, F.; Wellmeyer, P.; Xu, S.X. Do Clients’ Enterprise Systems Affect Audit Quality and Efficiency? Contemp. Account. Res. 2017, 34, 1975–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F. Mutual Monitoring and Agency Problems. SSRN Electron. J. 2014, 2406191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.-Y.; Lau, C.-M.; Foley, S. Strategic human resource management, firm performance, and employee relations climate in China. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huy, Q.N.; Xiao, Z. How middle managers manage the political environment to achieve market goals: Insights from China’s state-owned enterprises. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 676–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, M.; Ma, C. Anti-corruption and corporate environmental responsibility: Evidence from China’s anti-corruption campaign. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 72, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron-Tudor, A.; Deliu, D.; Farcane, N.; Dontu, A. Managing change with and through blockchain in accountancy organizations: A systematic literature review. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021, 34, 477–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Mo, X. Smarter and Prosperous: Digital Transformation and Enterprise Performance. Systems 2023, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Q.; Liu, J. Anti-corruption campaign in China: Good news or bad news for firm value? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 25, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. China’s anti-corruption shock and resource reallocation in the energy industry. Energy Econ. 2021, 96, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Walker, G. How much does owner type matter for firm performance? Manufacturing firms in China 1998–2007. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ho, K.C. Does the presence of executives with a legal background affect stock price crash risk? Corp. Gov. 2022, 31, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.H.; Merkoulova, Y.; Veld, C. Credit risk assessment and executives’ legal expertise. Rev. Account. Stud. 2023, 28, 2361–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Tong, X.; Jia, X. Executives’ Legal Expertise and Corporate Innovation. Corp. Gov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaya, D.; Williamson, I.O.; Zhang, X. Combining Patent Law Expertise with R&D for Patenting Performance. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I.; Markos, E.; Swani, K.; Peña, P. When data security goes wrong: Examining the impact of stress, social contract violation, and data type on consumer coping responses following a data breach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, A.; Southworth, A.; Heinz, J.P. Lawyers of the Right: Networks and Organization. Law Soc. Inq. 2007, 32, 883–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Liu, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, W. Unpacking urban network as formed by client service relationships of law firms in China. Cities 2022, 122, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chierici, R.; Tortora, D.; Del Giudice, M.; Quacquarelli, B. Strengthening digital collaboration to enhance social innovation capital: An analysis of Italian small innovative enterprises. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 22, 610–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yoon, S.S. Government efficiency and enterprise innovation—Evidence from China. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2019, 27, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, Y. Rent-Seeking, political connection, and actual performance: Evidence from Chinese privately-owned listed companies. J. Financ. Res. 2010, 10, 135–157. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0rU-DchPtsvyks_8emQ62p0xSQAN-7udXHrVzGWB1BdfJtw8MuSmbWr-nurOpK87SriTibD-fVzDzhiMgIudMkTfk5p2AjBMd-oSVbzhCA_TcMdZ2YqLxgVypkQ6xMjs&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 May 2024). (In Chinese).

- Bertrand, M.; Mullainathan, S. Do people mean what they say? Implication for subjective survey data. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lei, X.; Wu, W. Can digital investment improve corporate environmental performance?—Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xing, M. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Audit Pricing. Audit. Res. 2021, 3, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. How do family firms respond strategically to the digital transformation trend: Disclosing symbolic cues or making substantive changes? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, S.K. Rent Seeking, Earning Management and Agency Cost: How Do They Impact Equity Value? Indian Evidence. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.M.; Borini, F.M.; Oliveira, M.d.M. Interorganizational cooperation and process innovation: The dynamics of national vs foreign location of partners. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 31, 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larcker, D.F.; Rusticus, T.O. On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. J. Account. Econ. 2010, 49, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Q. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Corporate Sustainability: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J. Digital Economy Development, Allocation of Data Elements and Productivity Growth in Manufacturing Industry. Economist 2021, 10, 41–50. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0rU-DchPtssKnZt2pHq-EgPsPGcPI742Ci7zl93-M-t-4meh3Xnh5WwxdwkMX_wKpIKs9CFXpuhNVyskdqNCZgqUsXeuEvjtpjMeUy94SY-SK2BR9Qpr-eV5lKrD6dwRLu95We6ZMelY4AXpDjuJuA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CH (accessed on 1 May 2024). (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, E.A. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and look forward. Stat. Sci. 2010, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser-Plautz, B.; Schmidthuber, L. Digital government transformation as an organizational response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Measuring Firm Size in Empirical Corporate Finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.W.; Walls, J.L.; Dowell, G.W.S. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletkanycza, M.A.; Blackb, S.S. Bound by the past? Experience-based effects on commitment to the strategic status quo. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, L.S.; Jiang, J.; Wang, I.Y. What’s My Style? The Influence of Top Managers on Voluntary Corporate Financial Disclosure. Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 1131–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nell, P.C.; Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G.; Schmitt, J. Avoiding digitalization traps: Tools for top managers. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Fleisch, E.; Lamprecht, C.; Wortmann, F. Growth paths for overcoming the digitalization paradox. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, N.E.; Dong, J.Q.; Broekhuizen, T.; Verhoef, P.C. Business value of SME digitalisation: When does it pay off more? Eur. J. Inform. Syst. 2024, 33, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, M.; Kumar, V.; Harmeling, C.; Singh, S.; Zhu, T.; Chen, J.; Duncan, T.; Fortin, W.; Rosa, E. Insight is power: Understanding the terms of the consumer-firm data exchange. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.; Koharki, K. The association between corporate general counsel and firm credit risk. J. Account. Econ. 2016, 61, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, F.; Cai, X.; Liu, H. How does trust affect alliance performance? The mediating role of resource sharing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 45, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.F.; Petraite, M. Industry 4.0 technologies, digital trust and technological orientation: What matters in open innovation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zheng, L.; Lin, B. Does Rent-Seeking Affect Environmental Regulation? Evidence From the Survey Data of Private Enterprises in China. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Olson, E.M.; Hult, G.T.M. The moderating influence of strategic orientation on the strategy formation capability–performance relationship. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).