Exploring Factors Influencing ChatGPT-Assisted Learning Satisfaction from an Information Systems Success Model Perspective: The Case of Art and Design Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

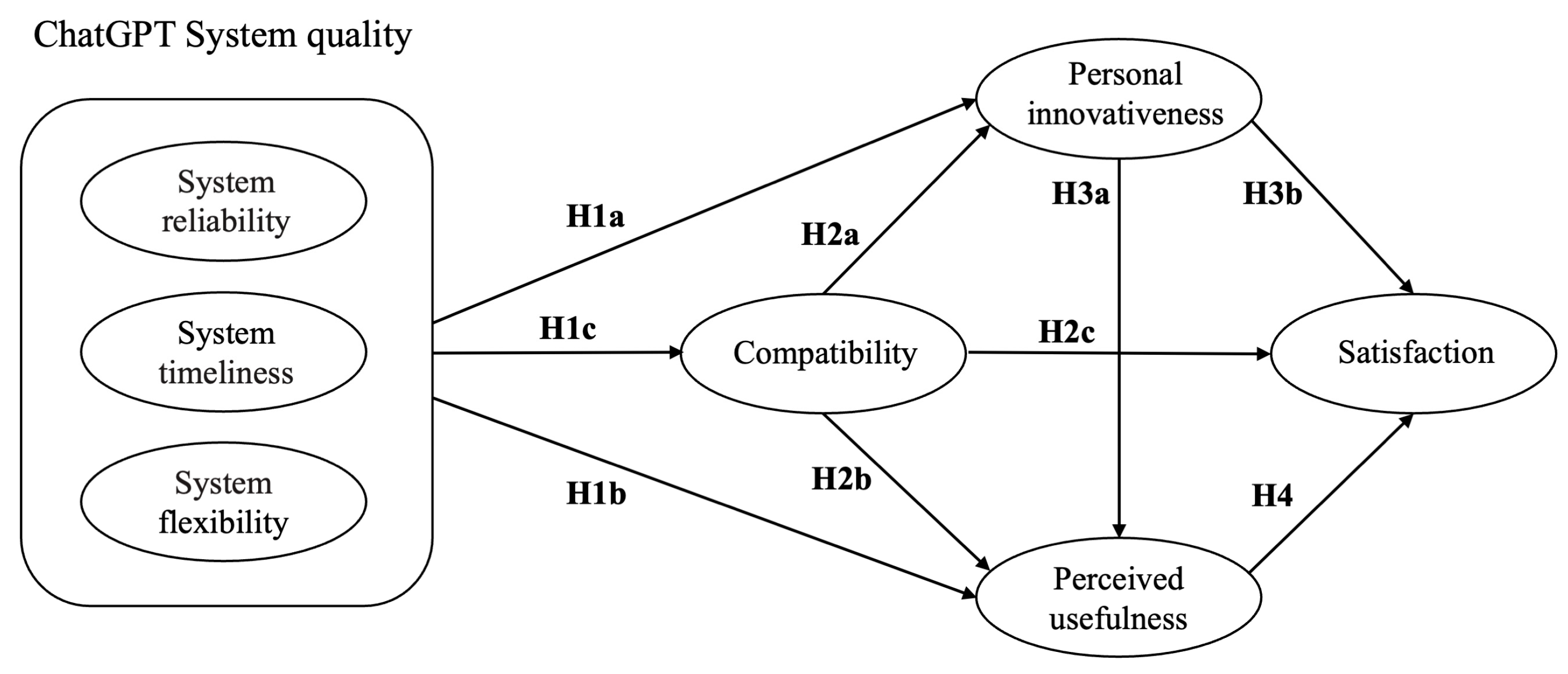

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Applications of ChatGPT in Art and Design Education

2.2. Information System Success Model (ISSM)

2.2.1. ChatGPT System Quality

2.2.2. Compatibility

2.2.3. Personal Innovativeness

2.2.4. Perceived Usefulness

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Questionnaire Development

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

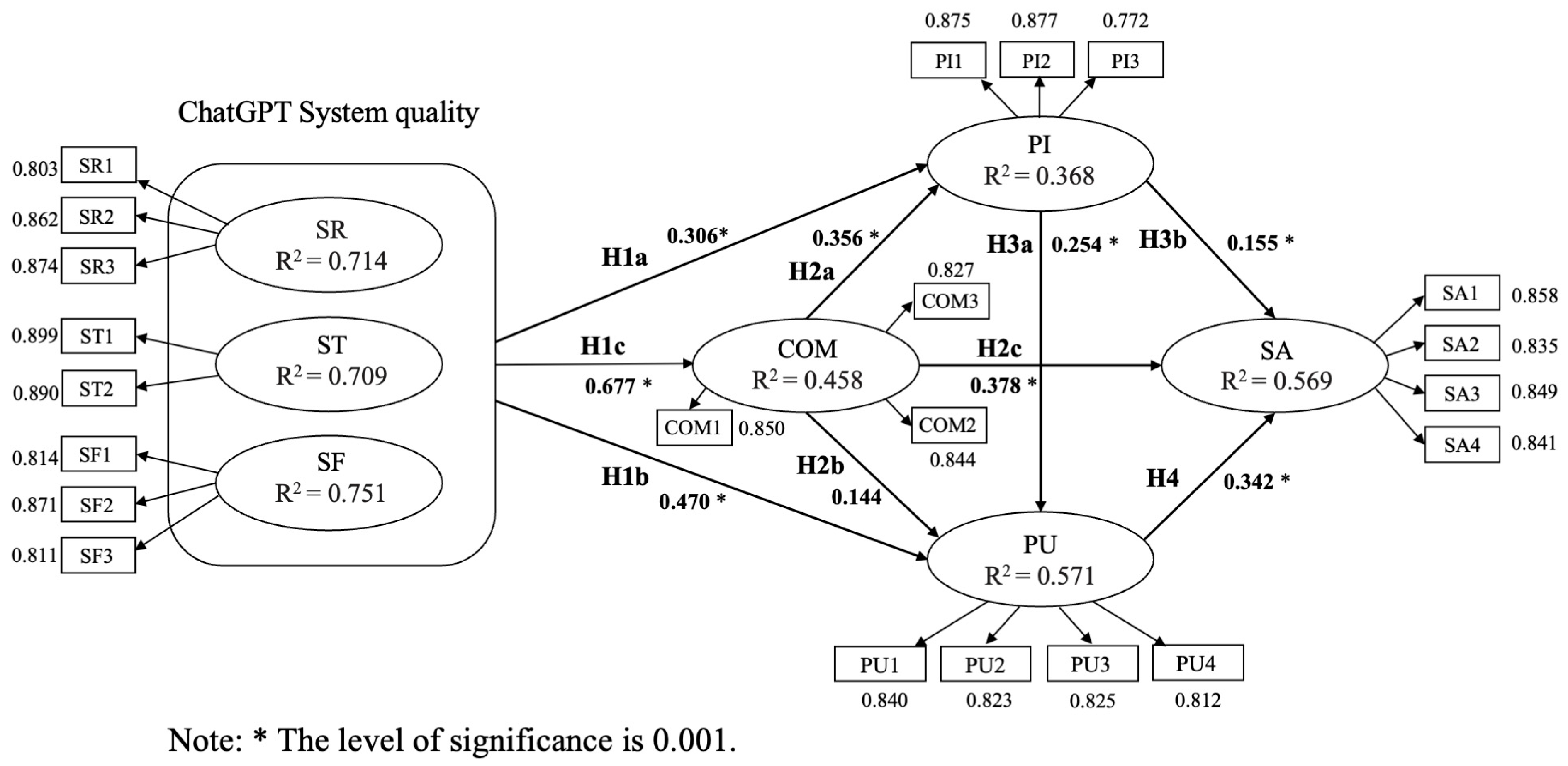

4.2. Assessment of Structural Model

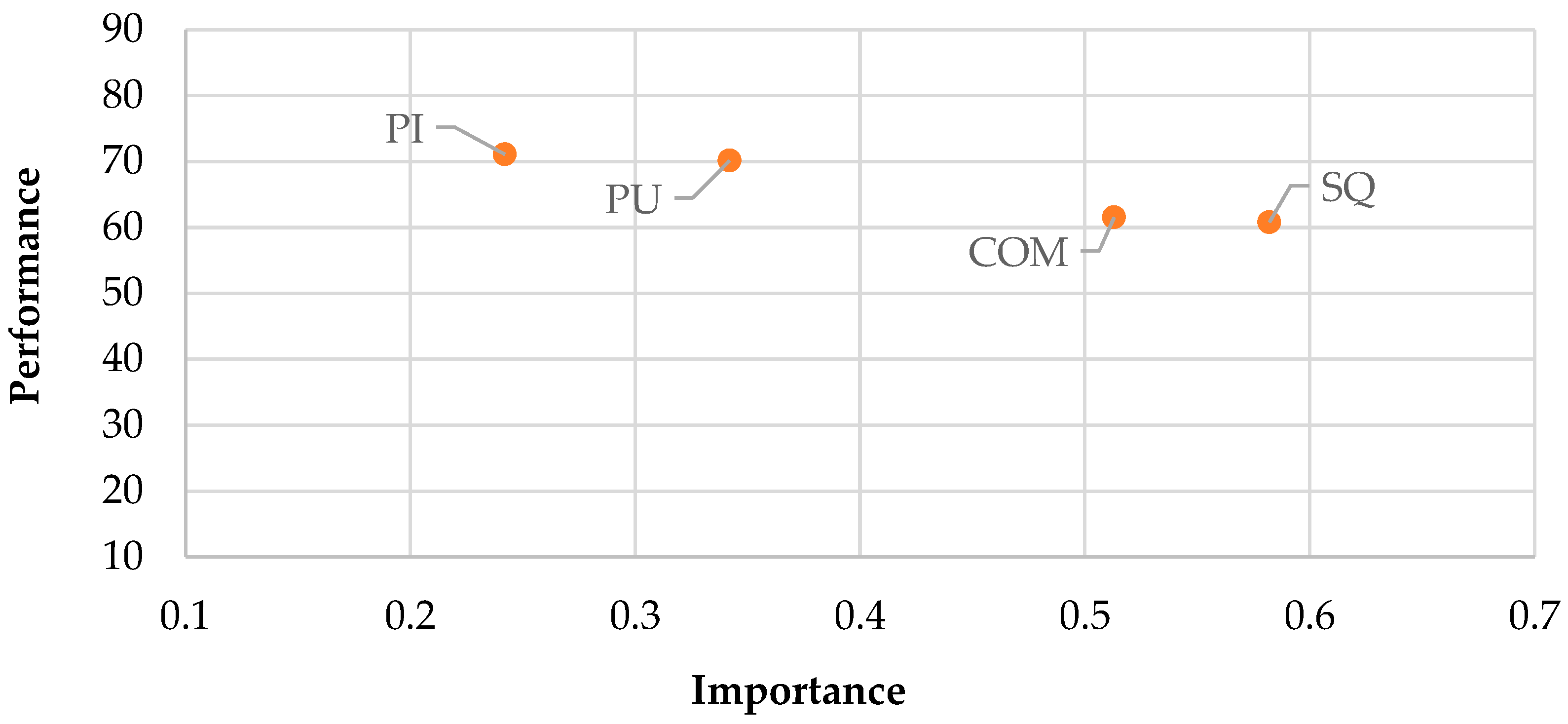

4.3. Importance–Performance Map Analysis (IPMA)

4.4. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of PLS-SEM and IPMA Results

5.2. Discussion of Configurational Results

5.2.1. High-Satisfaction Configurations

5.2.2. Low-Satisfaction Configurations

6. Conclusions

7. Research Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Items

| Construct | Items | References |

| System reliability | SR1 Using ChatGPT for Q&A is feasible. | [135] |

| SR2 The content generated by ChatGPT is reliable. | ||

| SR3 The operating system of ChatGPT is trustworthy. | ||

| System timeliness | ST1 ChatGPT responds to my needs quickly. | |

| ST2 ChatGPT provides me with knowledge content in a timely manner. | ||

| System flexibility | SF1 ChatGPT can adapt to my various needs. | |

| SF2 ChatGPT can flexibly respond to my anticipated needs. | ||

| SF3 ChatGPT can meet my diverse requirements. | ||

| Compatibility | COM1 ChatGPT aligns with my learning values. | [42] |

| COM2 ChatGPT fits my learning style. | ||

| COM3 ChatGPT meets my learning needs. | ||

| Personal innovativeness | PI1 I am willing to try and learn about ChatGPT. | [127] |

| PI2 I am open to new methods related to ChatGPT. | ||

| PI3 I believe I have the ability to master new functions of ChatGPT. | ||

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 ChatGPT enables me to complete tasks more quickly. | [136] |

| PU2 ChatGPT is helpful for my learning. | ||

| PU3 ChatGPT improves my work efficiency. | ||

| PU4 ChatGPT makes it easier to generate a variety of learning materials. | ||

| Satisfaction | SA1 I am satisfied with my experience of using ChatGPT. | |

| SA2 I am satisfied with the content generated by ChatGPT. | ||

| SA3 Using ChatGPT has met my expectations. | ||

| SA4 I am satisfied with the overall effectiveness of ChatGPT. |

References

- Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, C. Empowering education development through AIGC: A systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 17485–17537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.N.; Wu, Y.; Luo, Z. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on curriculum development in global higher education institutions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 547–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Chang, X. Research on the Application Path of AIGC in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the Wuhan International Conference on E-business, Wuhan, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.-L.; Liu, Y.-C.; Dong, M.-Q.; Lu, C.-C. Integrating AIGC into product design ideation teaching: An empirical study on self-efficacy and learning outcomes. Learn. Instr. 2024, 92, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. Applications and Challenges of AI in English Teaching: Comparative Analysis and Quantitative Assessment Methods for AIGC-Assisted Writing Evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Digital Classroom & Smart Learning, Shanghai, China, 27–29 September 2024; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, X.; Lin, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wan, H. Who will benefit from AIGC: An empirical study on the intentions to use artificial intelligence generated content in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 20627–20651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Noetel, M.; Liao, K.; Greiff, S. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence in Generative Content for enhancing motivation in learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2024, 116, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yang, Z.; Jaehong, K. AIGC changes in teaching practice in higher education visual design courses: Curriculum and teaching methods. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Xu, M.; Patros, P.; Wu, H.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, K.; Fuller, S.; Singh, M.; Arora, P.; Parlikad, A.K. Transformative effects of ChatGPT on modern education: Emerging Era of AI Chatbots. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 4, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazkani, O. Revolutionizing education of art and design through ChatGPT. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: The Power and Dangers of ChatGPT in the Classroom; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Zhong, X. Artificial intelligence-based creative thinking skill analysis model using human–computer interaction in art design teaching. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 100, 107957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego, M.; Usca, N.; Salguero, J.; Quevedo, W. Creative thinking in art and design education: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, T. STEAM by another name: Transdisciplinary practice in art and design education. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 2018, 119, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, T. Facilitating meta-learning in art and design education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2011, 30, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran Zailuddin, M.F.N.; Nik Harun, N.A.; Abdul Rahim, H.A.; Kamaruzaman, A.F.; Berahim, M.H.; Harun, M.H.; Ibrahim, Y. Redefining creative education: A case study analysis of AI in design courses. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2024, 17, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, A.F.C.A. Leveraging generative AI solutions in art and design education: Bridging sustainable creativity and fostering academic integrity for innovative society. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Paris, France, 2023; p. 01102. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekera, T.; Hosseini, Z.; Perera, U. Can artificial intelligence support creativity in early design processes? Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2025, 23, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Xiong, M. A new art design method based on AIGC: Analysis from the perspective of creation efficiency. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Intelligent Design (ICID), Xi’an, China, 20–22 October 2023; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Guo, C.; Dou, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, F.-Y. Could ChatGPT Imagine: Content control for artistic painting generation via large language models. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Lu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Wang, F.-Y. Can ChatGPT boost artistic creation: The need of imaginative intelligence for parallel art. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Exploring the impact of ChatGPT on art creation and collaboration: Benefits, challenges and ethical implications. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 14, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Mandal, S.; Das, P.; Kaur, T.; JP, S.; Nedungadi, P. University Students as Early Adopters of ChatGPT: Innovation Diffusion Study; Springer Science: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaisal, R.; Hatem, M.; Salloum, A.; Al Saidat, M.R.; Salloum, S.A. Forecasting the acceptance of ChatGPT as educational platforms: An integrated SEM-ANN methodology. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: The Power and Dangers of ChatGPT in the Classroom; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, H.; Liu, B. Factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT in high education: An integrated model with PLS-SEM and fsQCA approach. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241289835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S.; DeLone, W.; McLean, E. Measuring information systems success: Models, dimensions, measures, and interrelationships. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-W.; Guo, Y. Beyond the screen: Understanding consumer engagement with live-stream shopping from the perspective of the information system success model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2026, 88, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.W.; Bae, S.-K.; Ryu, J.-H.; Kim, K.N.; An, C.-H.; Chae, Y.M. Performance evaluation of public hospital information systems by the information system success model. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2015, 21, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.H.; Alshammari, R.A. An integration of expectation confirmation model and information systems success model to explore the factors affecting the continuous intention to utilise virtual classrooms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efiloğlu Kurt, Ö. Examining an e-learning system through the lens of the information systems success model: Empirical evidence from Italy. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, K.; Ayaz, A. Validation of the Delone and McLean information systems success model: A study on student information system. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 4709–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Ngo, T.V.N.; Dao, V.T.; Do, N.D.; Pham, T.V. Exploring higher education students’ continuance usage intention of ChatGPT: Amalgamation of the information system success model and the stimulus-organism-response paradigm. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2024, 41, 556–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.N.-L.; Tee, M.; Koay, K.Y. Discovering students’ continuous intentions to use ChatGPT in higher education: A tale of two theories. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2024, 13, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, U.; Mester, G.; Milic Marjanovic, B. Assessing the success of artificial intelligence tools: An evaluation of chatgpt using the information system success model. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. INDECS 2024, 22, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chang, S.-T.; Chou, P.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Chu, C.; Hsieh, F.; Tseng, G. Exploring users’ continuous use intention of ChatGPT based on the is success model and technology readiness. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 6, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Anand, V.; Sharma, D.; Vishnoi, S.K. Influence of ChatGPT in professional communication–moderating role of perceived innovativeness. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2025, 42, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Abu-Hijleh, B.; Alsewari, A.A. Examining the impact of Generative AI on social sustainability by integrating the information system success model and technology-environmental, economic, and social sustainability theory. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 9405–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeh, H.N.; Kee, D.M.H.; Mohammed, R.B.; Albarwary, S.A.; Khalilov, S. ChatGPT in the Malaysian Classroom: Assessing Student Acceptance and Effectiveness Through UTAUT2 and IS Success Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 22nd International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Istanbul, Turkey, 29 March–1 April 2025; pp. 583–592. [Google Scholar]

- Shuhaiber, A.; Kuhail, M.A.; Salman, S. ChatGPT in higher education-A Student’s perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 17, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.T.A. The perception by university students of the use of ChatGPT in education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (Online) 2023, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhuo, Z.; Lin, J. Does ChatGPT play a double-edged sword role in the field of higher education? An in-depth exploration of the factors affecting student performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J. Engineering education in the era of ChatGPT: Promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Kuwait, Kuwait, 1–4 May 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kohnke, L.; Moorhouse, B.L.; Zou, D. ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. Relc J. 2023, 54, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassopoulos, S.; Manoli, P.; Gouvi, M.; Lavidas, K.; Komis, V. The use of ChatGPT as a learning tool to improve foreign language writing in a multilingual and multicultural classroom. Adv. Mob. Learn. Educ. Res. 2023, 3, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. The rise of ChatGPT: Exploring its potential in medical education. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomae, A.V.; Witt, C.M.; Barth, J. Integration of ChatGPT into a course for medical students: Explorative study on teaching scenarios, students’ perception, and applications. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e50545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R.; Yilmaz, F.G.K. Augmented intelligence in programming learning: Examining student views on the use of ChatGPT for programming learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Boudouaia, A.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y. Would ChatGPT-facilitated programming mode impact college students’ programming behaviors, performances, and perceptions? An empirical study. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, V.; Luximon, Y. Understanding the perception of design students towards ChatGPT. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meron, Y.; Araci, Y.T. Artificial intelligence in design education: Evaluating ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for post-graduate course development. Des. Sci. 2023, 9, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, X.; Zheng, X.; Huang, Y.; Tu, Y. Exploring the AIGC-driven co-creation model in art and design education: Insights from a student workshop and exhibition. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Tung, F.-W. ChatGPT in Design Practice: Redefining Collaborative Design Process with Future Designers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Gothenburg, Sweden, 22–27 June 2025; pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos, E.; Inal, Y.; Monllaó, C.V.; Johansen, E.A.; Hermansen, M. Integrating AI into Design Ideation: Assessing ChatGPT’s Role in Human-Centered Design Education. Authorea Prepr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, B.O.; Mwangi, E.K.; Okoth, A.A.; Njeri, A.W. Integrating Generative AI and ChatGPT in Design Education: Impacts on Critical Thinking Development. Int. J. Graph. Des. 2025, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, S. Measuring the impact of ChatGPT on fostering concept generation in innovative product design. Electronics 2023, 12, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclachlan, R.; Adams, R.; Lauro, V.; Murray, M.; Magueijo, V.; Flockhart, G.; Hasty, W. Chat-GPT: A clever search engine or a creative design assistant for students and industry? In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education: Rise of the Machines: Design Education in the Generative AI Era, Brighton, UK, 5–6 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Almulla, M.A. Investigating influencing factors of learning satisfaction in AI ChatGPT for research: University students perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Huang, T.-C.; Shu, Y.; Chiang, Y.-H. Investigating the Influence of Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness, and Excitement on User Satisfaction with ChatGPT: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Technologies and Learning, Oslo, Norway, 5–7 August 2025; pp. 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.; Tong, M.; Tsang, E.Y.; Chu, K.; Tsang, W. Exploring Students’ Perceptions and Satisfaction of Using GenAI-ChatGPT Tools for Learning in Higher Education: A Mixed Methods Study. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsri, N.; Tripak, O.; Bao, Y. Do learners exhibit a willingness to use ChatGPT? An advanced two-stage SEM-neural network approach for forecasting factors influencing ChatGPT adoption. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2025, 22, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.; Elie-Dit-Cosaque, C.; Straub, D.W. Examining trust in information technology artifacts: The effects of system quality and culture. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 24, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorla, N.; Somers, T.M.; Wong, B. Organizational impact of system quality, information quality, and service quality. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhao, K.; Stylianou, A. The impacts of information quality and system quality on users’ continuance intention in information-exchange virtual communities: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.-N. Assessing the benefits of ChatGPT for business: An empirical study on organizational performance. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 76427–76436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. An empirical study on the educational application of ChatGPT. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, A. Customer adoption of Chat GPT for web development and programming assistance in the Zimbabwe tech industry. In Proceedings of the International Student Conference on Business, Education, Economics, Accounting, and Management (ISC-BEAM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 3–4 September 2024; pp. 1931–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S.; McLean, E.R. A meta-analytic assessment of the DeLone and McLean IS success model: An examination of IS success at the individual level. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Shamsuddin, A.; Aziati, N. The relationship between system quality, information quality, and organizational performance. Int. J. Knowl. Res. Manag. E-Commer. 2014, 4, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H. Understanding AI tool engagement: A study of ChatGPT usage and word-of-mouth among university students and office workers. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 85, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birolini, A. Quality and Reliability of Technical Systems: Theory, Practice, Management; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alhumaid, K.; Alshaafi, A.; Akour, I.; Bettayeb, A.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.A. A comparative analysis of chatgpt and google in educational settings: Understanding the influence of mediators on learning platform adoption. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: The Power and Dangers of ChatGPT in the Classroom; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar]

- Atalan, A. The ChatGPT application on quality management: A comprehensive review. J. Manag. Anal. 2025, 12, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kfairy, M. Factors impacting the adoption and acceptance of ChatGPT in educational settings: A narrative review of empirical studies. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, S.-C. What drives mobile commerce?: An empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A.S.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Dahri, N.A. Exploring factors influencing the acceptance of ChatGPT in higher education: A smart education perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, L.; Guo, J.; Yu, G. Assessment of University Students’ behavioral Intentions to Use ChatGPT: A Comprehensive Application Based on the Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model. Preprint 2024, 2024061835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T. Online learning usage within Yemeni higher education: The role of compatibility and task-technology fit as mediating variables in the IS success model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: Madison Ave, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Yan, J.; Cai, N. ChatGPT in higher education: Factors influencing ChatGPT user satisfaction and continued use intention. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1354929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikgoz, F.; Elwalda, A.; De Oliveira, M.J. Curiosity on cutting-edge technology via theory of planned behavior and diffusion of innovation theory. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Alyoussef, I.Y.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Kamin, Y.B. Integrating innovation diffusion theory with technology acceptance model: Supporting students’ attitude towards using a massive open online courses (MOOCs) systems. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Naghshineh, N.; Rodríguez, O.A.; Keshavarz, H.; Lund, B. In ChatGPT We Trust? Unveiling the Dynamics of Reuse Intention and Trust Towards Generative AI Chatbots among Iranians. Infosci. Trends 2024, 1, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, I.A.; Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.A. A conceptual framework for determining metaverse adoption in higher institutions of gulf area: An empirical study using hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A conceptual and operational definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J. Verifying the link of innovativeness to the confirmation-expectation model of ChatGPT of students in learning. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2025, 23, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.A.; Hatem, M.; Salloum, A.; Alfaisal, R. Envisioning ChatGPT’s Integration as Educational Platforms: A Hybrid SEM-ML Method for Adoption Prediction. In Artificial Intelligence in Education: The Power and Dangers of ChatGPT in the Classroom; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Rani, M.; Rani, G.; Rani, V. Human-machine dialogues unveiled: An in-depth exploration of individual attitudes and adoption patterns toward AI-powered ChatGPT systems. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2024, 26, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Park, Y.; Wang, H. The mediating effect of user satisfaction and the moderated mediating effect of AI anxiety on the relationship between perceived usefulness and subscription payment intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.H.; Babu, E. The mediating role of satisfaction in the relationship between perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and students’ behavioural intention to use ChatGPT. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C.C.; Colman, A.M. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol. 2000, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, G.C.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Roldán, J.L. Prediction-oriented modeling in business research by means of PLS path modeling: Introduction to a JBR special section. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4545–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alin, A. Multicollinearity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.-J.; Leong, L.-Y.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lee, V.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Mobile social tourism shopping: A dual-stage analysis of a multi-mediation model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C.C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 51. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J. Identifying single necessary conditions with NCA and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, I.O.; Woodside, A.G. Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Witt, M.A.; Aguilera, R.V.; Verbeke, A. The contributions of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M.J.; Jones, P.; Pickernell, D. Country-based comparison analysis using fsQCA investigating entrepreneurial attitudes and activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Tian, J.; Liu, Z. Exploring the usage behavior of generative artificial intelligence: A case study of ChatGPT with insights into the moderating effects of habit and personal innovativeness. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 8190–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadewo, S.T.; Ratnawati, S.; Giovanni, A.; Widayanti, I. The Influence of Personal Innovativeness on ChatGPT Continuance Usage Intention among Students. SATESI J. Sains Teknol. Dan Sist. Inf. 2025, 5, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Senali, M.G.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B.; Rejeb, A. Determinants of ChatGPT adoption among students in higher education: The moderating effect of trust. Electron. Libr. 2025, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Jhee, S.Y.; Han, S.-L. The Impact of Chat GPT’s Quality Factors on~ Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Enjoyment, and~ Continuous Usage Intention Using the IS Success Model. Asia Mark. J. 2025, 26, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarzouqi, A.; Aburayya, A.; Salloum, S.A. Prediction of user’s intention to use metaverse system in medical education: A hybrid SEM-ML learning approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 43421–43434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S., Sr.; Almarzouqi, A., Sr.; Salloum, A., Jr.; Alfaisal, R., Sr. Unlocking the Potential of ChatGPT in Medical Education and Practice. JMIR Prepr. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mehmood, S.; Khan, S.U. Navigating innovation in the age of AI: How generative AI and innovation influence organizational performance in the manufacturing sector. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 36, 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Cha, M.C.; Yoon, S.H.; Lee, S.C. Not merely useful but also amusing: Impact of perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment on the adoption of AI-powered coding assistant. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 6210–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Li, N.; Al-Adwan, A.; Abbasi, G.A.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Habibi, A. Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ intentions to use metaverse-based learning platforms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15381–15413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batouei, A.; Nikbin, D.; Foroughi, B. Acceptance of ChatGPT as an auxiliary tool enhancing travel experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 2744–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeh, H.N. What drives IT students toward ChatGPT? Analyzing the factors influencing students’ intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Erbil, Iraq, 22–25 April 2024; pp. 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- Sabraz Nawaz, S.; Fathima Sanjeetha, M.B.; Al Murshidi, G.; Mohamed Riyath, M.I.; Mat Yamin, F.B.; Mohamed, R. Acceptance of ChatGPT by undergraduates in Sri Lanka: A hybrid approach of SEM-ANN. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2024, 21, 546–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, D.; Sun, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Kim, J.H. Analyzing behavioral intentions toward Generative Artificial Intelligence: The case of ChatGPT. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Li, L.; Hossain, M.S.; Zabin, S. Investigating students’ behavioral intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, A. ‘From technology adoption to consumption’: Effect of pre-adoption expectations from fitness applications on usage satisfaction, continual usage, and health satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cai, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, K.; Lu, C. Integrating AIGC with design: Dependence, application, and evolution-a systematic literature review. J. Eng. Des. 2025, 36, 758–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, C. Exploring the digital transformation of generative ai-assisted foreign language education: A socio-technical systems perspective based on mixed-methods. Systems 2024, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Meng, Y.; Tang, L. Reconsidering teacher assessment literacy in GenAI-enhanced environments: A scoping review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2025, 165, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jing, Y.; Shen, S. A systematic literature review on the application of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) in teaching within higher education: Instructional contexts, process, and strategies. Internet High. Educ. 2025, 65, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. The effect of AI quality on customer experience and brand relationship. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, D.; Gu, C.; Wei, W.; Chen, J. Research on high school students’ behavior in art course within a virtual learning environment based on SVVR. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1218959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Category | Number (n = 435) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 206 | 47.4 |

| Female | 229 | 52.6 | |

| Age | 18–21 | 377 | 86.7 |

| 22–26 | 58 | 13.3 | |

| Level of study | Undergraduate | 389 | 89.4 |

| Graduate | 46 | 10.6 | |

| Frequency | Less than once a week | 58 | 13.3 |

| About once a week | 126 | 29.0 | |

| Several times a week | 43 | 9.9 | |

| About once a day | 130 | 29.9 | |

| Several times a day | 78 | 17.9 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings (>0.7) | VIF (<0.3) | α (>0.7) | CR (>0.7) | AVE (>0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System reliability | SR1 | 0.803 | 1.503 | 0.802 | 0.884 | 0.717 |

| SR2 | 0.862 | 1.927 | ||||

| SR3 | 0.874 | 1.990 | ||||

| System timeliness | ST1 | 0.899 | 1.564 | 0.750 | 0.889 | 0.800 |

| ST2 | 0.890 | 1.564 | ||||

| System flexibility | SF1 | 0.814 | 1.551 | 0.777 | 0.871 | 0.693 |

| SF2 | 0.871 | 1.852 | ||||

| SF3 | 0.811 | 1.560 | ||||

| Compatibility | COM1 | 0.850 | 1.703 | 0.792 | 0.878 | 0.706 |

| COM2 | 0.844 | 1.784 | ||||

| COM3 | 0.827 | 1.571 | ||||

| Personal innovativeness | PI1 | 0.875 | 2.034 | 0.795 | 0.880 | 0.711 |

| PI2 | 0.877 | 2.047 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.772 | 1.419 | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 | 0.840 | 2.006 | 0.843 | 0.895 | 0.680 |

| PU2 | 0.823 | 1.825 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.825 | 1.886 | ||||

| PU4 | 0.812 | 1.780 | ||||

| Satisfaction | SA1 | 0.858 | 2.071 | 0.868 | 0.910 | 0.716 |

| SA2 | 0.835 | 2.040 | ||||

| SA3 | 0.849 | 2.150 | ||||

| SA4 | 0.841 | 2.037 |

| SR | ST | SF | COM | PI | PU | SA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR1 | 0.803 | 0.488 | 0.475 | 0.515 | 0.453 | 0.563 | 0.519 |

| SR2 | 0.862 | 0.464 | 0.507 | 0.507 | 0.385 | 0.467 | 0.493 |

| SR3 | 0.874 | 0.457 | 0.545 | 0.531 | 0.388 | 0.493 | 0.495 |

| ST1 | 0.527 | 0.899 | 0.551 | 0.483 | 0.402 | 0.545 | 0.511 |

| ST2 | 0.463 | 0.890 | 0.532 | 0.400 | 0.427 | 0.569 | 0.504 |

| SF1 | 0.490 | 0.517 | 0.814 | 0.496 | 0.356 | 0.458 | 0.519 |

| SF2 | 0.518 | 0.525 | 0.871 | 0.518 | 0.390 | 0.500 | 0.570 |

| SF3 | 0.494 | 0.468 | 0.811 | 0.534 | 0.381 | 0.502 | 0.547 |

| COM1 | 0.522 | 0.441 | 0.526 | 0.850 | 0.540 | 0.527 | 0.572 |

| COM2 | 0.481 | 0.380 | 0.535 | 0.844 | 0.416 | 0.452 | 0.546 |

| COM3 | 0.534 | 0.422 | 0.502 | 0.827 | 0.458 | 0.543 | 0.574 |

| PI1 | 0.443 | 0.413 | 0.397 | 0.494 | 0.875 | 0.519 | 0.494 |

| PI2 | 0.386 | 0.409 | 0.378 | 0.456 | 0.877 | 0.567 | 0.488 |

| PI3 | 0.390 | 0.347 | 0.368 | 0.478 | 0.772 | 0.405 | 0.460 |

| PU1 | 0.462 | 0.545 | 0.482 | 0.499 | 0.498 | 0.840 | 0.538 |

| PU2 | 0.496 | 0.504 | 0.483 | 0.483 | 0.508 | 0.823 | 0.564 |

| PU3 | 0.504 | 0.516 | 0.457 | 0.517 | 0.466 | 0.825 | 0.556 |

| PU4 | 0.513 | 0.488 | 0.506 | 0.501 | 0.485 | 0.812 | 0.527 |

| SA1 | 0.524 | 0.540 | 0.567 | 0.639 | 0.527 | 0.612 | 0.858 |

| SA2 | 0.490 | 0.438 | 0.533 | 0.535 | 0.451 | 0.527 | 0.835 |

| SA3 | 0.493 | 0.466 | 0.557 | 0.528 | 0.478 | 0.551 | 0.849 |

| SA4 | 0.497 | 0.467 | 0.561 | 0.562 | 0.468 | 0.545 | 0.841 |

| SR | ST | SF | COM | PI | PU | SA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | 0.847 | 0.714 | 0.762 | 0.766 | 0.605 | 0.729 | 0.711 |

| ST | 0.554 | 0.895 | 0.792 | 0.639 | 0.599 | 0.782 | 0.700 |

| SF | 0.602 | 0.605 | 0.832 | 0.791 | 0.576 | 0.722 | 0.798 |

| COM | 0.611 | 0.495 | 0.620 | 0.840 | 0.709 | 0.739 | 0.806 |

| PI | 0.482 | 0.463 | 0.452 | 0.564 | 0.843 | 0.721 | 0.685 |

| PU | 0.599 | 0.622 | 0.585 | 0.606 | 0.593 | 0.825 | 0.771 |

| SA | 0.593 | 0.567 | 0.656 | 0.672 | 0.570 | 0.662 | 0.846 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std Beta | p-Value | Results | R2 | Q2 | f2 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | SQ→PI | 0.306 | 0.000 | Support | 0.368 | 0.254 | 0.080 | 1.846 |

| H1b | SQ→PU | 0.470 | 0.000 | Support | 0.571 | 0.382 | 0.259 | 1.994 |

| H1c | SQ→COM | 0.677 | 0.000 | Support | 0.458 | 0.319 | 0.846 | 1.000 |

| H2a | COM→PI | 0.356 | 0.000 | Support | 0.109 | 1.846 | ||

| H2b | COM→PU | 0.144 | 0.003 | Support | 0.024 | 2.046 | ||

| H2c | COM→SA | 0.378 | 0.000 | Support | 0.569 | 0.399 | 0.188 | 1.759 |

| H3a | PI→PU | 0.254 | 0.000 | Support | 0.095 | 1.583 | ||

| H3b | PI→SA | 0.155 | 0.000 | Support | 0.032 | 1.717 | ||

| H4 | PU→SA | 0.342 | 0.000 | Support | 0.146 | 1.852 |

| Constructs | Items | Substantive Factor Loading (R1) | Substantive Variance (R12) | Method Factor Loading (R2) | Method Variance (R22) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System reliability | SR1 | 0.799 | 0.638 | 0.136 | 0.018 |

| SR2 | 0.865 | 0.748 | −0.077 | 0.006 | |

| SR3 | 0.875 | 0.766 | −0.050 | 0.003 | |

| System timeliness | ST1 | 0.896 | 0.803 | 0.020 | 0.000 |

| ST2 | 0.893 | 0.797 | −0.020 | 0.000 | |

| System flexibility | SF1 | 0.811 | 0.658 | −0.020 | 0.000 |

| SF2 | 0.872 | 0.760 | −0.023 | 0.001 | |

| SF3 | 0.812 | 0.659 | 0.044 | 0.002 | |

| Compatibility | COM1 | 0.846 | 0.716 | 0.054 | 0.003 |

| COM2 | 0.852 | 0.726 | −0.123 | 0.015 | |

| COM3 | 0.822 | 0.676 | 0.065 | 0.004 | |

| Personal innovativeness | PI1 | 0.875 | 0.766 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| PI2 | 0.877 | 0.769 | −0.016 | 0.000 | |

| PI3 | 0.773 | 0.598 | 0.010 | 0.000 | |

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 | 0.842 | 0.709 | −0.049 | 0.002 |

| PU2 | 0.821 | 0.674 | 0.025 | 0.001 | |

| PU3 | 0.825 | 0.681 | −0.001 | 0.000 | |

| PU4 | 0.811 | 0.658 | 0.026 | 0.001 | |

| Satisfaction | SA1 | 0.848 | 0.719 | 0.176 | 0.031 |

| SA2 | 0.841 | 0.707 | −0.098 | 0.010 | |

| SA3 | 0.854 | 0.729 | −0.064 | 0.004 | |

| SA4 | 0.842 | 0.709 | −0.018 | 0.000 | |

| Average | 0.843 | 0.712 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| Latent Constructs | Performance Impact Total Effect (Importance) | Index Values (Performance) |

|---|---|---|

| System quality | 0.582 | 60.821 |

| Compatibility | 0.513 | 61.562 |

| Personal innovativeness | 0.242 | 71.099 |

| Perceived usefulness | 0.342 | 70.172 |

| Variable | Satisfaction | ~Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| SR | 0.753 | 0.818 | 0.502 | 0.527 |

| ~SR | 0.564 | 0.540 | 0.826 | 0.764 |

| ST | 0.818 | 0.764 | 0.618 | 0.558 |

| ~ST | 0.527 | 0.588 | 0.738 | 0.797 |

| SF | 0.819 | 0.796 | 0.552 | 0.518 |

| ~SF | 0.503 | 0.538 | 0.782 | 0.807 |

| COM | 0.794 | 0.830 | 0.518 | 0.523 |

| ~COM | 0.543 | 0.538 | 0.832 | 0.796 |

| PI | 0.793 | 0.778 | 0.577 | 0.546 |

| ~PI | 0.537 | 0.568 | 0.766 | 0.782 |

| PU | 0.810 | 0.795 | 0.553 | 0.524 |

| ~PU | 0.515 | 0.544 | 0.784 | 0.800 |

| Configuration | Satisfaction | Dissatisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| SR | ⊗ |  | • |  | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ |

| ST | • | • | • | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||

| SF | • | • | • | • | ⊗ | ⊗ | |

| COM |  |  | • | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | |

| PI | • |  |  | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||

| PU |  | • |  | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | |

| Consistency | 0.943 | 0.944 | 0.948 | 0.953 | 0.947 | 0.946 | 0.947 |

| Raw coverage | 0.332 | 0.549 | 0.555 | 0.530 | 0.531 | 0.516 | 0.526 |

| Unique coverage | 0.050 | 0.035 | 0.040 | 0.016 | 0.047 | 0.032 | 0.042 |

| Overall solution coverage | 0.655 | 0.605 | |||||

| Overall solution consistency | 0.923 | 0.932 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhuo, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, S. Exploring Factors Influencing ChatGPT-Assisted Learning Satisfaction from an Information Systems Success Model Perspective: The Case of Art and Design Students. Systems 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010007

Zhuo Z, Li D, Chen J, Chen X, Wang S. Exploring Factors Influencing ChatGPT-Assisted Learning Satisfaction from an Information Systems Success Model Perspective: The Case of Art and Design Students. Systems. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuo, Ziqing, Dongning Li, Jiangjie Chen, Xinqiang Chen, and Shuaijun Wang. 2026. "Exploring Factors Influencing ChatGPT-Assisted Learning Satisfaction from an Information Systems Success Model Perspective: The Case of Art and Design Students" Systems 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010007

APA StyleZhuo, Z., Li, D., Chen, J., Chen, X., & Wang, S. (2026). Exploring Factors Influencing ChatGPT-Assisted Learning Satisfaction from an Information Systems Success Model Perspective: The Case of Art and Design Students. Systems, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010007