Approaching the Black Hole by Numerical Simulations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Numerical Approaches

- (i)

- Simulations mainly treating the dynamics of the black hole environment on a fixed metric;

- (ii)

- Simulations that ray-trace photons that are affected by strong gravity, and;

- (iii)

- Simulations that solve the time-dependent Einstein equations.

2.1. Dynamics on Fixed Space-Time

2.2. Dynamics of Interacting Compact Objects

2.3. Radiation—Propagation of Light Close to a Black Hole

3. Dynamics and Feedback—(Magneto-)Hydrodynamic Simulations

4. Radiation from Simulated Gas Dynamics

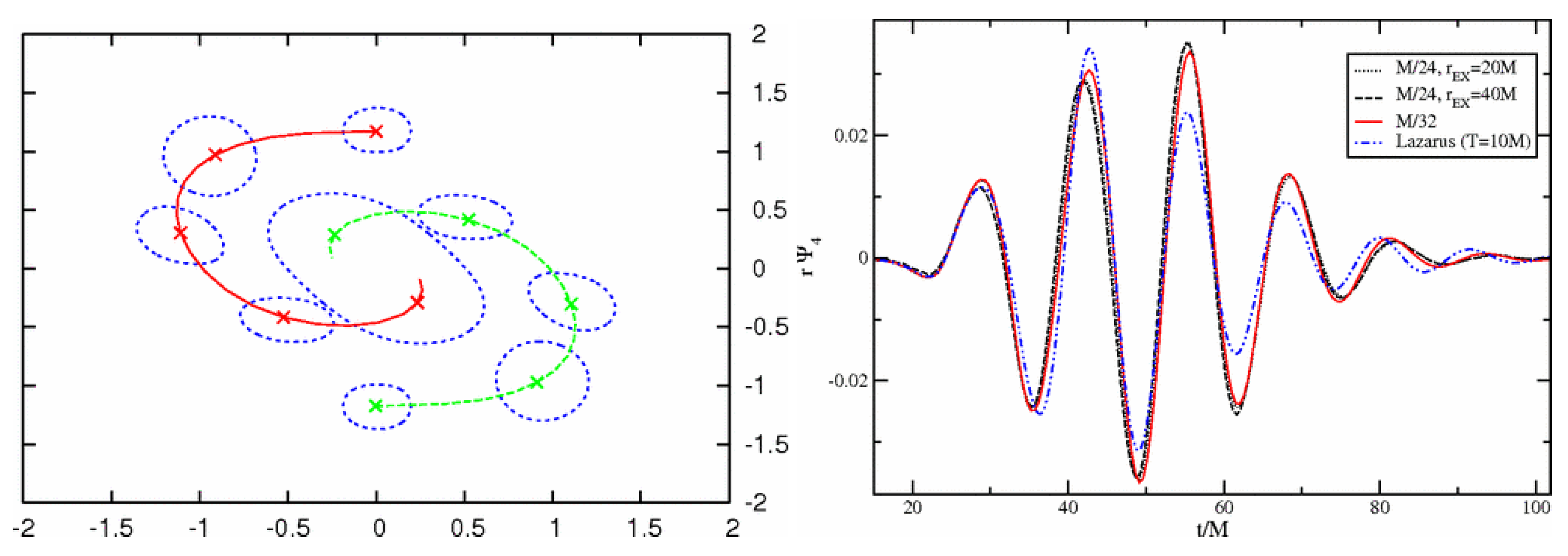

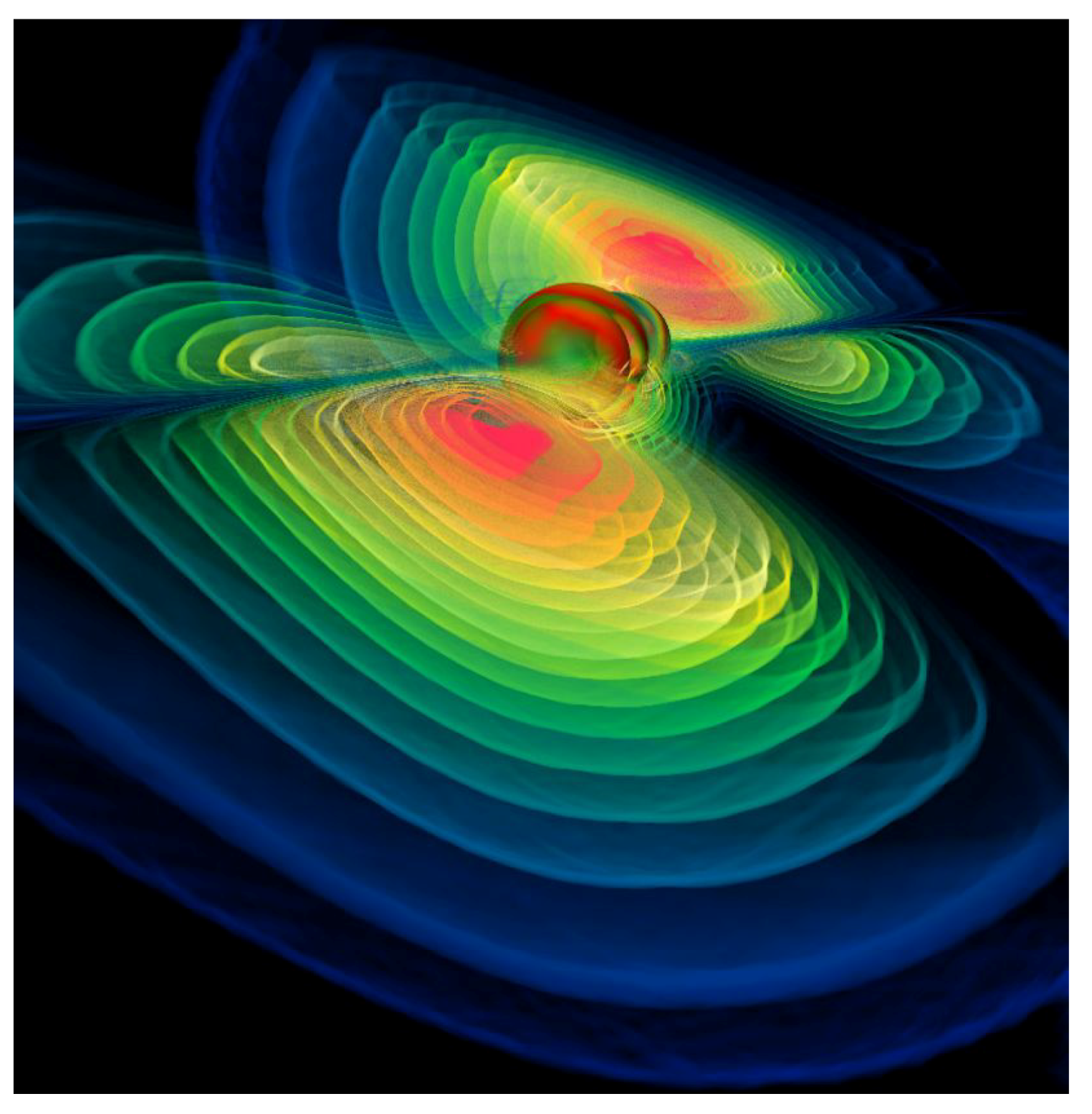

5. Compact Object Mergers

6. Summary and Outlook

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AGN | Active galactic nuclei |

| EHT | Event Horizon Telescope |

| GR-MHD | General relativistic magneto-hydrodynamics |

| ISCO | Innermost stable circular orbit |

| LIGO | Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory |

| MHD | Magneto-hydrodynamics |

References

- Mirabel, I.F.; Rodríguez, L.F. Sources of Relativistic Jets in the Galaxy. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 37, 409–443. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, A.C. Observational Evidence of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 50, 455–489. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, H. The Physics and Evolution of Active Galactic Nuclei; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shakura, N.I.; Sunyaev, R.A. Black holes in binary systems. Observational appearance. Astron. Astrophys. 1973, 24, 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, R.D.; McKee, C.F. Reverberation mapping of the emission line regions of Seyfert galaxies and quasars. Astrophys. J. 1982, 255, 419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, R.D.; Payne, D.G. Hydromagnetic flows from accretion discs and the production of radio jets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1982, 199, 883–903. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, R.D.; Znajek, R.L. Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1977, 179, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Lens-Like Action of a Star by the Deviation of Light in the Gravitational Field. Science 1936, 84, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refsdal, S. The gravitational lens effect. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1964, 128, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-F.; Davis, S.W.; Stone, J.M. Iron Opacity Bump Changes the Stability and Structure of Accretion Disks in Active Galactic Nuclei. Astrophys. J. 2016, 827, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.C.; Krolik, J.H.; Hawley, J.F. Direct Calculation of the Radiative Efficiency of an Accretion Disk Around a Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2009, 692, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.R. Numerical Study of Fluid Flow in a Kerr Space. Astrophys. J. 1972, 173, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R. Magnetohydrodynamics near a black hole. In Proceedings of the Marcel Grossman Meeting; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, J.F.; Smarr, L.L.; Wilson, J.R. A numerical study of nonspherical black hole accretion. I Equations and test problems. Astrophys. J. 1984, 277, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J.F.; Smarr, L.L.; Wilson, J.R. A numerical study of nonspherical black hole accretion. II—Finite differencing and code calibration. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 1984, 55, 211–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, J.-P.; Hawley, J.F. Three-dimensional Hydrodynamic Simulations of Accretion Tori in Kerr Spacetimes. Astrophys. J. 2002, 577, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, S.; Shibata, K.; Kudoh, T. Relativistic Jet Formation from Black Hole Magnetized Accretion Disks: Method, Tests, and Applications of a General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Numerical Code. Astrophys. J. 1999, 522, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zanna, L.; Zanotti, O.; Bucciantini, N.; Londrillo, P. ECHO: A Eulerian conservative high-order scheme for general relativistic magnetohydrodynamics and magnetodynamics. Astron. Astrophys. 2007, 473, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, J.-P.; Hawley, J.F. A Numerical Method for General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics. Astrophys. J. 2003, 589, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammie, C.F.; McKinney, J.C.; Tóth, G. HARM: A Numerical Scheme for General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics. Astrophys. J. 2003, 589, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, S. Magnetic extraction of black hole rotational energy: Method and results of general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations in Kerr space-time. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 67, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S. Direct numerical simulations of the Blandford-Znajek effect. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 326, L41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C. General relativistic force-free electrodynamics: A new code and applications to black hole magnetospheres. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 367, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.C.; Gammie, C.F.; McKinney, J.C.; Del Zanna, L. Primitive Variable Solvers for Conservative General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics. Astrophys. J. 2006, 641, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicol, G.S.; Kodama, T.; Koide, T.; Mota, P. Stability and causality in relativistic dissipative hydrodynamics. J. Phys. G Nuclear Phys. 2008, 35, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, W.A.; Lindblom, L. Stability and causality in dissipative relativistic fluids. Ann. Phys. 1983, 151, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C.; Narayan, R. Disc-jet coupling in black hole accretion systems—II. Force-free electrodynamical models. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2007, 375, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbus, S.A.; Hawley, J.F. A powerful local shear instability in weakly magnetized disks. I—Linear analysis. Astrophys. J. 1991, 376, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr, L. Mass Formula for Kerr Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr, L.; Cadez, A.; Dewitt, B.; Eppley, K. Collision of two black holes: Theoretical framework. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr, L.; York, J.W., Jr. Kinematical conditions in the construction of spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 1978, 17, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eardley, D.M.; Smarr, L. Time functions in numerical relativity: Marginally bound dust collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1979, 19, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anninos, P.; Massó, J.; Seidel, E.; Suen, W.-M.; Towns, J. Three-dimensional numerical relativity: The evolution of black holes. Phys. Rev. D 1995, 52, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S.R.; Seidel, E. Evolution of distorted rotating black holes. III. Initial data. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 54, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.; Scheel, M.A.; Pfeiffer, H.P. Comparison of binary black hole initial data sets. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.B.; Huq, M.F.; Klasky, S.A.; Klasky, S.A.; Scheel, M.A.; Abrahams, A.M.; Anderson, A.; Anninos, P.; Baumgarte, T.W.; Bishop, N.T.; et al. Boosted Three-Dimensional Black-Hole Evolutions with Singularity Excision. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittman, J.D.; Krolik, J.H.; Hawley, J.F. Light Curves from an MHD Simulation of a Black Hole Accretion Disk. Astrophys. J. 2006, 651, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T. GeoViS-Relativistic ray tracing in four-dimensional spacetimes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Über den Einfluß der Schwerkraft auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes. Ann. Phys. 1911, 340, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C. A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun’s Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1920, 220, 291–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.-P.; Bennett, D.P.; Fouqué, P. Discovery of a cool planet of 5.5 Earth masses through gravitational microlensing. Nature 2006, 439, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchra, J.; Gorenstein, M.; Kent, S.; Shapiro, I.; Smith, G.; Horine, E.; Perley, R. 2237 + 0305: A new and unusual gravitational lens. Astron. J. 1985, 90, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Narayan, R. Cosmological applications of gravitational lensing. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1992, 30, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-K.; Psaltis, D.; Özel, F. GRay: A Massively Parallel GPU-based Code for Ray Tracing in Relativistic Spacetimes. Astrophys. J. 2013, 777, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.; Agol, E.; Fragile, P.C.; McKinney, J.C. The Submillimeter Bump in Sgr A* from Relativistic MHD Simulations. Astrophys. J. 2010, 717, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J. A public code for general relativistic, polarised radiative transfer around spinning black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 462, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.-Y.; Yun, K.; Younsi, Z.; Yoon, S.-J. Odyssey: A Public GPU-based Code for General Relativistic Radiative Transfer in Kerr Spacetime. Astrophys. J. 2016, 820, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, F.H.; Paumard, T.; Gourgoulhon, E.; Perrin, G. GYOTO: A new general relativistic ray-tracing code. Class. Quant. Gravity 2011, 28, 225011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Narayan, R.; Sadowski, A.; Psaltis, D. HERO—A 3D general relativistic radiative post-processor for accretion discs around black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 451, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Zhang, B. The physics of gamma-ray bursts & relativistic jets. Phys. Rep. 2015, 561, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fragile, P.C.; Anninos, P. Hydrodynamic Simulations of Tilted Thick-Disk Accretion onto a Kerr Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2005, 623, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J.F. Three-dimensional simulations of black hole tori. Astrophys. J. 1991, 381, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragile, P.C.; Blaes, O.M.; Anninos, P.; Salmonson, J.D. Global General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Simulation of a Tilted Black Hole Accretion Disk. Astrophys. J. 2007, 668, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Teixeira, D.; Fragile, P.C.; Zhuravlev, V.V.; Ivanov, P.B. Conservative GRMHD Simulations of Moderately Thin, Tilted Accretion Disks. Astrophys. J. 2014, 796, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, A.; Narayan, R.; McKinney, J.C.; Tchekhovskoy, A. Numerical simulations of super-critical black hole accretion flows in general relativity. Astrophys. J. 2014, 439, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyed, R.; Pudritz, R.E. Numerical Simulations of Astrophysical Jets from Keplerian Disks. I. Stationary Models. Astrophys. J. 1997, 482, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porth, O.; Fendt, C. Acceleration and Collimation of Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Disk Winds. Astrophys. J. 2010, 709, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porth, O.; Fendt, C.; Meliani, Z.; Vaidya, B. Synchrotron Radiation of Self-collimating Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Jets. Astrophys. J. 2011, 737, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S.; Vlahakis, N.; Königl, A.; Barkov, M.V. Magnetic acceleration of ultrarelativistic jets in gamma-ray burst sources. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 394, 1182–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. Magnetically-driven jets from Keplerian accretion discs. Astron. Astrophys. 1997, 319, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F.; Bu, D.; Wu, M. Numerical Simulation of Hot Accretion Flows. II. Nature, Origin, and Properties of Outflows and their Possible Observational Applications. Astrophys. J. 2012, 761, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Gan, Z.; Narayan, R.; Sadowski, A.; Bu, D.; Bai, X. Numerical Simulation of Hot Accretion Flows. III. Revisiting Wind Properties Using the Trajectory Approach. Astrophys. J. 2015, 084, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Narayan, R. Hot Accretion Flows Around Black Holes. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 52, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Stone, J.M. Global Evolution of an Accretion Disk with a Net Vertical Field: Coronal Accretion, Flux Transport, and Disk Winds. Astrophys. J. 2018, 857, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanni, C.; Ferrari, A.; Rosner, R.; Bodo, G.; Massaglia, S. MHD simulations of jet acceleration from Keplerian accretion disks. The effects of disk resistivity. Astron. Astrophys. 2007, 469, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhnezami, S.; Fendt, C.; Porth, O.; Vaidya, B.; Ghanbari, J. Bipolar Jets Launched from Magnetically Diffusive Accretion Disks. I. Ejection Efficiency versus Field Strength and Diffusivity. Astrophys. J. 2012, 757, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanovs, D.; Fendt, C. An Extensive Numerical Survey of the Correlation Between Outflow Dynamics and Accretion Disk Magnetization. Astrophys. J. 2016, 825, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, J.-P.; Hawley, J.F. Global General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations of Accretion Tori. Astrophys. J. 2003, 592, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, J.-P.; Hawley, J.F.; Krolik, J.; Hirose, S. Magnetically Driven Accretion in the Kerr Metric. III. Unbound Outflows. Astrophys. J. 2005, 620, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C.; Gammie, C.F. A Measurement of the Electromagnetic Luminosity of a Kerr Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2004, 611, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Sadowski, A.; Penna, R.F.; Kulkarni, A.K. GRMHD simulations of magnetized advection-dominated accretion on a non-spinning black hole: Role of outflows. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 426, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porth, O.; Olivares, H.; Mizuno, Y.; Younsi, Z.; Rezzolla, L.; Moscibrodzka, M.; Falcke, H.; Kramer, M. The black hole accretion code. Comput. Astrophys. Cosmol. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbone, L.G.; Moncrief, V. Relativistic fluid disks in orbit around Kerr black holes. Astrophys. J. 1976, 207, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, R.F.; Kulkarni, A.; Narayan, R. A new equilibrium torus solution and GRMHD initial conditions. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 559, A116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, S.S. Observations of the Blandford-Znajek process and the magnetohydrodynamic Penrose process in computer simulations of black hole magnetospheres. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2005, 359, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C. Total and Jet Blandford-Znajek Power in the Presence of an Accretion Disk. Astrophys. J. 2005, 630, 5L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C.; Blandford, R.D. Stability of relativistic jets from rotating, accreting black holes via fully three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 394, L126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, R.F.; McKinney, J.C.; Narayan, R.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Shafee, R.; McClintock, J.E. Simulations of magnetized discs around black holes: effects of black hole spin, disc thickness and magnetic field geometry. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 408, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchekhovskoy, A.; Narayan, R.; McKinney, J.C. Efficient generation of jets from magnetically arrested accretion on a rapidly spinning black hole. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 418, L79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchekhovskoy, A.; Narayan, R.; McKinney, J.C. Black Hole Spin and The Radio Loud/Quiet Dichotomy of Active Galactic Nuclei. Astrophys. J. 2010, 711, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchekhovskoy, A.; McKinney, J.C. Prograde and retrograde black holes: whose jet is more powerful? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 423, L55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.C.; Krolik, J.H.; Hawley, J.F. Dependence of Inner Accretion Disk Stress on Parameters: The Schwarzschild Case. Astrophys. J. 2010, 711, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, N.; Del Zanna, L. A fully covariant mean-field dynamo closure for numerical 3 + 1 resistive GRMHD. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 428, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugli, M.; Del Zanna, L.; Bucciantini, N. Dynamo action in thick discs around Kerr black holes: high-order resistive GRMHD simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 440, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Fendt, C.; Noble, S.; Bugli, M. rHARM: Accretion and Ejection in Resistive GR-MHD. Astrophys. J. 2017, 834, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Fendt, C.; Vourellis, C. Jet Launching in Resistive GR-MHD Black Hole—Accretion Disk Systems. Astrophys. J. 2018, 859, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysopoulou, K.; Alic, D.; Palenzuela, C.; Rezzolla, L.; Giacomazzo, B. General-relativistic resistive magnetohydrodynamics in three dimensions: Formulation and tests. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 044020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela, C.; Lehner, L.; Reula, O.; Rezzolla, L. Beyond ideal MHD: Towards a more realistic modelling of relativistic astrophysical plasmas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 394, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Davis, S.W.; Narayan, R.; Kulkarni, A.K.; Penna, R.F.; McClintock, J.E. The eye of the storm: Light from the inner plunging region of black hole accretion discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 424, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, A.; Narayan, R.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Zhu, Y. Semi-implicit scheme for treating radiation under M1 closure in general relativistic conservative fluid dynamics codes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 429, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.R.; Ohsuga, K. A Numerical Treatment of Anisotropic Radiation Fields Coupled with Relativistic Resistive Magnetofluids. Astrophys. J. 2013, 772, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J.C.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Sadowski, A.; Narayan, R. Three-dimensional general relativistic radiation magnetohydrodynamical simulation of super-Eddington accretion using a new code HARMRAD with M1 closure. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 441, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucart, F. Monte Carlo closure for moment-based transport schemes in general relativistic radiation hydrodynamic simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2918, 475, 4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucart, F.; Haas, R.; Duez, M.D.; O’Connor, E.; Ott, C.D.; Roberts, L.; Kidder, L.E.; Lippuner, J.; Pfeiffer, H.P.; Scheel, M.A. Low mass binary neutron star mergers: Gravitational waves and neutrino emission. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 044019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.C.; Leung, P.K.; Gammie, C.F.; Book, L.G. Simulating the emission and outflows from accretion discs. Class. Quantum Gravity 2007, 24, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-K.; Psaltis, D.; Özel, F.; Narayan, R.; Sadowski, A. The Power of Imaging: Constraining the Plasma Properties of GRMHD Simulations using EHT Observations of Sgr A*. Astrophys. J. 2015, 799, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, S.M.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Quataert, E.; Chandra, M.; Gammie, C.F. Electron thermodynamics in GRMHD simulations of low-luminosity black hole accretion. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 454, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.R.; Ressler, S.M.; Dolence, J.C.; Tchekhovskoy, A.; Gammie, C.; Quataert, E. The Radiative Efficiency and Spectra of Slowly Accreting Black Holes from Two-temperature GRRMHD Simulations. Astrophys. J. 2017, 844, 24L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolence, J.C.; Gammie, C.F.; Moscibrodzka, M.; Leung, P.K. Grmonty: A Monte Carlo Code for Relativistic Radiative Transport. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 184, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.-Y.; Akiyama, K.; Asada, K. The Effects of Accretion Flow Dynamics on the Black Hole Shadow of Sagittarius A*. Astrophys. J. 2015, 831, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.-Y.; Wu, K.; Younsi, Z.; Asada, K.; Mizuno, Y.; Nakamura, M. Observable Emission Features of Black Hole GRMHD Jets on Event Horizon Scales. Astrophys. J. 2017, 845, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Zhu, Y.; Psaltis, D.; Sadowski, A. HEROIC: 3D general relativistic radiative post-processor with comptonization for black hole accretion discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 457, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, R.; McKinney, J.C.; Johnson, M.D.; Doeleman, S.S. Probing the Magnetic Field Structure in Sgr A* on Black Hole Horizon Scales with Polarized Radiative Transfer Simulations. Astrophys. J. 2017, 837, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaltis, D.; Özel, F.; Chan, C.-K.; Marrone, D.P. A General Relativistic Null Hypothesis Test with Event Horizon Telescope Observations of the Black Hole Shadow in Sgr A*. Astrophys. J. 2015, 814, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Keitel, D.; Forteza, X.J.; Husa, S.; London, L.; Bernuzzi, S.; Harms, E.; Nagar, A.; Hannam, M.; Khan, S.; Pürrer, M.; et al. The most powerful astrophysical events: Gravitational-wave peak luminosity of binary black holes as predicted by numerical relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 024006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centrella, J.; Baker, J.G.; Kelly, B.J.; van Meter, J.R. Black-hole binaries, gravitational waves, and numerical relativity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperhake, U. The numerical relativity breakthrough for binary black holes. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.G.; Centrella, J.; Choi, D.-I.; Koppitz, M.; van Meter, J. Gravitational-Wave Extraction from an Inspiraling Configuration of Merging Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 111102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügmann, B.; Tichy, W.; Jansen, N. Numerical Simulation of Orbiting Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 211101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, M.; Lousto, C.O.; Marronetti, P.; Zlochower, Y. Accurate Evolutions of Orbiting Black-Hole Binaries without Excision. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 111101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, F. Evolution of Binary Black-Hole Spacetimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcubierre, M.; Benger, W.; Brügmann, B.; Lanfermann, G.; Nerger, L.; Seidel, E.; Takahashi, R. 3D Grazing Collision of Two Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 271103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, P.; Herrmann, F.; Pollney, D.; Schnetter, E.; Seidel, E.; Takahashi, R.; Thornburg, J.; Ventrella, J. Accurate Evolution of Orbiting Binary Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, N.T.; Rezzolla, L. Extraction of gravitational waves in numerical relativity. Living Rev. Relat. 2016, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, F.; Faber, J.; Bentivegna, E.; Bode, T.; Diener, P.; Haas, R.; Hinder, I.; Mundim, B.C.; Ott, C.D.; Schnetter, E.; et al. The Einstein Toolkit: A community computational infrastructure for relativistic astrophysics. Class. Quantum Gravity 2012, 29, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mösta, P.; Mundim, B.C.; Faber, J.A.; Haas, R.; Noble, S.C.; Bode, T.; Löffler, F.; Ott, C.D.; Reisswig, C.; Schnetter, E. GRHydro: A new open-source general-relativistic magnetohydrodynamics code for the Einstein toolkit. Class. Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, K.; Healy, J.; Clark, J.A.; London, L.; Laguna, P.; Shoemaker, D. Georgia tech catalog of gravitational waveforms. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 204001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, J.; Lousto, C.O.; Zlochower, Y.; Campanelli, M. The RIT binary black hole simulations catalog. Class. Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 224001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abernathy, M.R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abernathy, M.R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Properties of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 241102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, M.; Schmidt, P.; Bohé, A.; Haegel, L.; Husa, S.; Ohme, F.; Pratten, G.; Pürrer, M. Simple Model of Complete Precessing Black-Hole-Binary Gravitational Waveforms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 151101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taracchini, A.; Buonanno, A.; Pan, Y.; Hinderer, T.; Boyle, M.; Hemberger, D.A.; Kidder, L.E.; Lovelace, G.; Mroué, A.H.; Pfeiffer, H.P.; et al. Effective-one-body model for black-hole binaries with generic mass ratios and spins. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 061502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Uryu, K. Simulation of merging binary neutron stars in full general relativity: Γ=2 case. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 61, 064001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Uryu, K. Merger of binary neutron stars of unequal mass in full general relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 68, 084020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Uryu, K. Merger of binary neutron stars with realistic equations of state in full general relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 71, 084021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özel, F.; Freire, P. Masses, Radii, and the Equation of State of Neutron Stars. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 54, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.W.; Lattimer, J.M.; Brown, E.F. The Neutron Star Mass-Radius Relation and the Equation of State of Dense Matter. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2013, 765, L5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotokezaka, K.; Kyutoku, K.; Okawa, H.; Shibata, M.; Kiuchi, K. Binary neutron star mergers: Dependence on the nuclear equation of state. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 124008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radice, D.; Bernuzzi, S.; Del Pozzo, W.; Roberts, L.F.; Ott, C.D. Probing Extreme-density Matter with Gravitational-wave Observations of Binary Neutron Star Merger Remnants. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2017, 842, L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, S.; Dietrich, T.; Nagar, A. Modeling the Complete Gravitational Wave Spectrum of Neutron Star Mergers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 091101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, Y.; Kiuchi, K.; Kyutoku, K.; Shibata, M.; Taniguchi, K. Dynamical mass ejection from the merger of asymmetric binary neutron stars: Radiation-hydrodynamics study in general relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 124046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauswein, A.; Stergioulas, N. Unified picture of the post-merger dynamics and gravitational wave emission in neutron star mergers. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 124056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidis, V. General relativistic simulations of compact binary mergers as engines for short gamma-ray bursts. Class. Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 084002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Fujibayashi, S.; Hotokezaka, K.; Kiuchi, K.; Kyutoku, K.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Tanaka, M. Modeling GW170817 based on numerical relativity and its implications. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 123012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; et al. GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, B.D.; Gold, R.; Paschalidis, V.; Etienne, Z.B.; Shapiro, S.L. Binary Black-Hole Mergers in Magnetized Disks: Simulations in Full General Relativity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 221102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, R.; Paschalidis, V.; Etienne, Z.B.; Shapiro, S.L.; Pfeiffer, H.P. Accretion disks around binary black holes of unequal mass: General relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations near decoupling. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 064060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügmann, B. Available online: http://wwwsfb.tpi.uni-jena.de/Projects/B7.shtml (accessed on 29 April 2019).

- Porth, O.; Chatterjee, K.; Narayan, R.; Gammie, C.F.; Mizuno, Y.; Anninos, P.; Baker, J.G.; Bugli, M.; Chan, C.K.; Davelaar, J.; et al. The Event Horizon General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Code Comparison Project. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.04923. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; Baloković, M.; Barrett, J.; Bintley, D.; et al. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Alberdi, A.; Alef, W.; Asada, K.; Azulay, R.; Baczko, A.K.; Ball, D.; Baloković, M.; Barrett, J.; Bintley, D.; et al. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. IV. Imaging the Central Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. 2019, 875, 4. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Interested readers can actually redo the modeling of the GW 150914 binary black hole merger gravitational wave signal using the “Einstein Toolkit”, see https://einsteintoolkit.org/gallery/bbh/. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fendt, C. Approaching the Black Hole by Numerical Simulations. Universe 2019, 5, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5050099

Fendt C. Approaching the Black Hole by Numerical Simulations. Universe. 2019; 5(5):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5050099

Chicago/Turabian StyleFendt, Christian. 2019. "Approaching the Black Hole by Numerical Simulations" Universe 5, no. 5: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5050099

APA StyleFendt, C. (2019). Approaching the Black Hole by Numerical Simulations. Universe, 5(5), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5050099