Abstract

We investigated within the Darmois–Israel thin-shell formalism the match of neutral and asymptotically flat, slowly rotating spacetimes (up to second order in the rotation parameter) when their boundaries are dynamic. It has several important applications in general relativistic systems, such as black holes and neutron stars, which we exemplify. We mostly focused on the stability aspects of slowly rotating thin shells in equilibrium and the surface degrees of freedom on the hypersurfaces splitting the matched slowly rotating spacetimes, e.g., surface energy density and surface tension. We show that the stability upon perturbations in the spherically symmetric case automatically implies stability in the slow rotation case. In addition, we show that, when matching slowly rotating Kerr spacetimes through thin shells in equilibrium, the surface degrees of freedom can decrease compared to their Schwarzschild counterparts, meaning that the energy conditions could be weakened. The frame-dragging aspects of the match of slowly rotating spacetimes are also briefly discussed.

1. Introduction

Although matching two spherically symmetric spacetimes is a simple task (see [1], for instance), this is not the case for axially symmetric ones [2]. Nevertheless, particular glues have already been applied to several scenarios and contexts in the slow rotation case. We mention, for instance, the collapse of slowly rotating thin shells (onto already formed black holes [3], generating slowly rotating black holes [4], or associated with regular interior spacetimes [5]), the analysis of the kinematical effects that slowly rotating spacetime glues should exhibit [6,7], and scalar fields non-minimally coupled to glued spacetimes [8]. Concerning the match of slowly rotating spacetimes up to second order in the rotation parameter, the work of de La Cruz and Israel [3] is noteworthy. They did this for the first time by joining the Minkowski and the Kerr spacetimes using prescribed axially symmetric hypersurfaces in equilibrium. It was shown that there are infinite ways of joining these spacetimes, each characterized by a spinning shell with a different degree of ellipticity. In addition, the rigid rotation of observers inside the shell with the shell itself does not occur generally. It was not the interest of that work to assess the stability of the equilibrium radii.

Another more recent example of an interesting glue is the work of Uchikata and Yoshida [5], who investigated the matching of a slowly rotating Kerr–Newman spacetime with the de Sitter one using a thin shell in equilibrium (its stability was not investigated either). As expected, they also found that the surface degrees of freedom are polar-angle-dependent on the thin shell. Cases were found where the surface energy density could be negative, but the authors deemed them unphysical. For further interesting slowly rotating thin-shell applications, see [9,10,11,12,13,14] and the references therein.

Clear aspects of matching axially symmetric spacetimes are the possibility of having manifolds without singularities and the possibility of more realistic models for astrophysical systems. In addition, the dragging of inertial frames is inherent in these spacetimes. We show here how this kinematic effect would allow us to scrutinize layered systems in astrophysics, shedding some light on their constitution.

We addressed the problem of matching neutral, arbitrary, slowly rotating Hartle spacetimes split by dynamic hypersurfaces, examining some of their subtleties. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been performed before. We limit our analysis to the second order in the rotation parameter since it is not known how to generically glue two axially symmetric spacetimes with arbitrary rotation parameters. As a byproduct of our investigation, we show, for instance, that the stability of thin shells in the spherically symmetric case automatically implies the stability of thin shells when slow rotation (up to second order in the rotation parameter) is present. In addition, we show that there are (realistic) situations where the corrections to the surface energy density and surface tension in the spherically symmetric case are negative. This seems to be of interest, as it would point to the likelihood of violating some energy conditions in some regions of surfaces of discontinuity in the non-perturbative context.

This article is organized as follows. In the next section, we deal with the problem of matching two slowly rotating Hartle spacetimes split by a dynamic hypersurface. Section 3 is devoted to the solution of the established system of equations for static and away-from-equilibrium hypersurfaces. The generalizations of the surface energy density and surface tension in the case of slow rotation are presented in Section 4. Kinematic effects associated with our generic glues are addressed in Section 5. In Section 6, we apply our formalism to the important case of matching two Kerr spacetimes and investigate the behavior of surface quantities and some aspects of the energy conditions. A summary and many astrophysical applications of our work can be found in Section 7.

We use geometric units throughout the article and the metric signature .

2. Matching Slowly Rotating Spacetimes

In the slowly rotating case, following Hartle [15], we assumed that each spacetime that we glue can be written as

where

As usual, we define as the second-order Legendre polynomial [].

In these approximations, we go up to the second order in the rotation parameter, fingerprinted by the dummy (dimensionless) quantity “”. It was put in Equation (1) just as a mere indicator of the order of the rotational expansion taken into account. The functions as given by Equations (2)–(4) are to be found by Einstein’s equations in the scope of axially symmetric solutions (see Reference [15] for the associated equations, some solutions, and properties). The background spacetime that is the seed for the Hartle metric is a spherically symmetric one (for the case of a BH spacetime, it would be the Schwarzschild metric), as can be seen by putting in Equation (1).

To match two spacetimes (which can then be used to obtain spacetimes made up of an arbitrary number of glues), one must also know their common hypersurface (that is to say, it must be well-defined), as well as how the coordinates of each manifold are related to the ones defined on such a hypersurface. Once this is obtained, finding the surface energy–momentum tensor that would allow such a glue is more of an algebraic exercise, made possible mainly by Lanczos’ and Israel’s seminal works [1,16,17,18].

To begin with, let us choose the intrinsic coordinates of the splitting hypersurface, defined as , as . For now, is just a label for a time-like coordinate on . Further ahead, such a choice will be justified when we try to relate it to the proper time measured by observers on , at least to some order in “”. We shall assume that the equation for is given by

Up to this point, R and B are unknown functions, and “” indicates the rotational order of the factors involved. In addition, let us assume that the spacetime coordinates relate to the ones of the hypersurface as

Just not to overload the notation, we dropped the “±” indexes that should be present in the coordinates of the spacetimes to be matched. Such labels would be related to a region above (“+”) and below (“−”) , naturally defined by its normal vector.

With the ansatz given by Equations (5) and (6), our task is to find the functions A, B, C, R, and T that lead the metrics given by Equation (1) to be continuous when projected onto (continuity of the first fundamental form). This is the first junction condition to be imposed when matching spacetimes whose resultant one leads to a distributional solution to Einstein’s equations [18]. From Equations (1) and (6), we have to impose that (for any F, ):

and

to eliminate the first-order terms in the rotational parameter of the induced metric and retrieve our spherically symmetric solution with as the proper time on . From Equation (8), we see that the well-definiteness of the induced metric does not constrain ; it is a free function whose dynamics will be related to the spherically symmetric configuration. We know from such a case that its determination is only possible when an equation of state for the (perfect-like) fluid on is given [1,19,20].

Since we are working perturbatively in “”, we can expand the functions A and B up to the second-order Legendre polynomials in the same fashion as it was done previously for . Therefore, let us assume

and

On the hypersurface, , the functions , , , , and (see Equations (2)–(4)) have their radial dependence just replaced by R, given that they are already second-order functions in the rotational parameter. This notwithstanding, the spherically symmetric function on the hypersurface , on account of Equations (5) and (9), changes to

similar to . Therefore, further corrections appear when one works up to . The one given by Equation (11) is due to the shape change of due to rotation.

From Equations (1), (6)–(8) and (11), the induced metric on can be cast as

If we now substitute Equations (2)–(4), (9) and (10) into Equation (12), the well-definiteness of the induced metric on is guaranteed by means of the following conditions:

with

In the above equations, we defined as the jump of A across Σ. We stress that each of Equations (13) and (14) is two equations, related to each region (±) defined by . We then have eight unknown functions, , to seven equations, Equations (13)–(17). The missing equation is related to the freedom in deforming the shape of the surface, splitting the two glued regions of space for a fixed eccentricity. Note that (or any given constant) renders Equation (16) an identity, and in this case, we are left with a system of six equations to six variables. Equations (13)–(18) allow us to express the (continuous) induced metric on in a simplified way, namely

where we define for a given quantity F on , . Of course, that simplified way of expressing the induced metric is due to our coordinate freedom on .

We stress that all of our previous reasoning remains the same if we perform the change , with an arbitrary constant. This is related to the freedom we always have in choosing the ellipticity of when matching two slowly rotating spacetimes. In addition, is not the proper-time on if one takes into account Equations (13)–(18). This is not a problem since the coordinates on can be chosen freely. Finally, we recall that the thin-shell formalism leads to surface quantities that are independent of the coordinate systems of the glued spacetimes and the hypersurface. We chose Hartle’s spacetime and because, respectively, this is physically appealing and convenient for slowly rotating extended systems such as neutron stars, and this leads to a simple induced metric on .

3. Static and Away-from-Equilibrium Thin Shells

We solved Equations (13)–(18) for the case , which is not endowed with a dynamics, namely when or = constant. This case is very important since it tests the consistency of the system of equations obtained previously. In addition, it gives us the requisites for having static glues of slowly rotating spacetimes. For this case, Equation (8) gives us that . It is not difficult to show that the solution to the above system of equations is

with a jump-free () and arbitrary constant. In this case, the induced metric, Equation (19), does not depend on , as expected. It can be checked that this is the only case where such an aspect rises concomitantly with the self-consistency of the system of equations. This justifies the choice of Equations (13)–(18).

It is worth emphasizing that = constant does not automatically guarantee the thin shell’s stability upon perturbations. This is just the case whenever is bound. From Equation (5), one sees that stability will be ensured just when both and are bound functions. In particular, for our analysis to be meaningful, that should be fulfilled by the latter function. After meeting this demand, the only one left is the bound nature of . This can be analyzed within the thin-shell formalism in the spherically symmetric case, and we know that it is summarized by the search of the minima of an effective potential [1]. As a result, in the stable case, is automatically bound and could be approximated by a harmonic function around R with a very small amplitude. It is simple to show in this case that the corrections to Equations (20)–(23) coming from our field Equations (13)–(17) will also be proportional to oscillating functions around . More specifically, if , where and is a constant, then , , and . This must be the case mathematically since we have a system of inhomogeneous trigonometric functions to solve. From Equations (5) and (6), it also makes physical sense that and ( and ) oscillate in the same way. Thus, we concluded that the stability of in the spherically symmetric case also implies its stability in the presence of small rotations. This is a very important result and will be used in subsequent sections when we elaborate on the energy conditions of hypersurfaces in the case of slow rotation.

4. Energy–Momentum Tensor for a Slowly Rotating Thin Shell

We now determine the energy–momentum tensor on that guarantees the glue of two slowly rotating spacetimes whose boundary is dynamic. We must find the normal vector to to do so. Generally, the normal vector to a given hypersurface is [18]

where , depending on whether is space-like or time-like, respectively. In addition, Equation (24) ensures that is a unit vector in the direction of growth of .

Let us now calculate the gradient to , . From Equation (5),

From Equations (1), (6), (24) and (25), one obtains

In the above normal components, we assumed that is time-like, thus in Equation (24). The contravariant components of the normal vector can be worked out simply using .

Now, we proceed with the calculations of the extrinsic curvature, defined as [18]

Off-diagonal terms in appear for slowly rotating spacetimes. First, we recall that, in the spherically symmetric case

and

For the first-order corrections in “”, we also have

According to Lanczos’ equation [16,17], the surface energy–momentum leading to a distributional solution to Einstein’s equations is

where is the trace of the extrinsic curvature.

In the spherically symmetric () case, is a diagonal tensor concerning the coordinates, i.e.,

This is the energy–momentum tensor for a comoving frame. Thus, the fluid on is perfect-like, i.e.,

Whenever one works up to the first-order approximation in “”, similar results as the above ones also hold in the coordinate system , with defined by Equation (6).

Now, we turn to the case where, up to second order, corrections in “” are worked out. From what we have pointed out previously, the form of the surface energy–momentum in this case in the coordinate system should generically resemble

Because we are just inserting rotation into the problem, we still expect the fluid on to be perfect-like. Thus, from Equation (36), we have that

The above equation shows that is invariant; hence, it will be the same for every coordinate system on . The results coming from lower orders of approximation tell us that we should accept solutions of the form

The only solution coming from Equation (38) that satisfies such prerequisites is

where we fixed the arbitrary quantities and coming from the eigenvalue approach by the normalization condition and

For the (invariant) surface tension, from Equation (38), we generically have that

For the slowly rotating thin-shell case, the above equation becomes

Note that the second-order correction in “” to is polar-angle-dependent, and it is different from the one to (see Equations (33), (34), (41) and (43)). We finally stress that our perturbative analyses break down whenever the surface quantities in the spherically symmetric are null. That is natural because we assumed that the slow-rotation case is only a small correction to the spherically symmetric case.

5. Dragging of Inertial Frames for Glued Slowly Rotating Spacetimes

We now briefly discuss some kinematic effects related to the match of two slowly rotating Hartle’s spacetimes (see Equation (1)). Let us first analyze the aspects of a static observer inside the rotating thin shell. This observer can be described by or from Equation (6) equivalently . Thus, in the fixed stars’ frame of reference (stationary observers at infinity), such an observer is rotating with the angular velocity:

where we also used Equation (7). We recall that can easily be read off from Equation (8). Equation (44) states that, far away external observers see internal ones rotating, even when , namely when the inner spacetime is spherically symmetric. Such an effect is the well-known dragging of inertial frames, or the Lense–Thirring effect [21]. The case where is interesting because it shows that the rotation of the shell intrinsically induces a rotation of the observers inside it. Whenever the inner spacetime is also endowed with a rotational parameter (), naturally, it also contributes to the final angular velocity fixed stars ascribe to internal observers at rest, as evidenced by Equation (44). Even more remarkable in this case is the possibility of the disappearance of the dragging of inertial frames (see Equation (44)). This is so even when and the shell parameters are given by convenient values of the inner spacetime parameters.

Furthermore, about distant observers, the rotation of the thin shell can be obtained. We know that concerning the frame with coordinates , the shell rotates with angular velocity

where we recall that the “” dependence on Equation (40) is merely an indicator that the associated surface energy–momentum tensor is of a given order on the rotational parameters . Taking into account Equations (6) and (45), we have that the angular velocity of the shell relative to the fixed stars is

where also Equation (7) was taken into account, and we recall that is given by Equation (8). For completeness, we remark that the relative velocity of observers inside the shell with the shell itself could be obtained by Equations (44) and (46) and always vanishes at the associated “gravitational radius” of the external spacetime (), showing that rigid dragging takes place in this case [3]. Nevertheless, whenever a nontrivial inner spacetime is considered, in principle, configurations always exist that would lead the observers inside the shell to corotate with the thin shell. The interest in the effect of frame dragging [22,23] naturally lies in the fact that its measurement could give direct information about the stratification of spacetime.

6. Matching Slowly Rotating Kerr Spacetimes

A case of physical interest concerning the glue of slowly rotating spacetimes would be where they are of Kerr types. This could be, for instance, a model for slowly rotating neutral thin shells of matter collapsing onto Kerr black holes as could happen in AGNs. A natural advantage of this match is the geometric simplicity of both regions. We know that the Kerr metric in the Boyer–Lindquist coordinates () is [21]

where

This solution has two arbitrary constants: the system’s total mass, M, and its total angular momentum per unit mass, a. The above metric has horizons at . We shall not elaborate anymore on the well-known properties of this solution.

We emphasize that Hartle’s coordinates () differ from the Boyer–Lindquist ones. It is simple, though tedious, to show that the coordinate transformations linking the aforesaid coordinate systems up to second order in “” (here, ) are (see, e.g., Beltracchi et al. [12])

The coordinate transformations given by Equations (51) and (52) are necessary to apply the formalism we developed previously for matching two slowly rotating spacetimes. The Kerr metric components up to second order in “” in Hartle’s coordinates are

and

We now investigate the induced shell quantities (surface energy density and tension) due to small rotations. For example, let us choose thin shells in equilibrium at the radial coordinate , being the mass of the outer Schwarzschild spacetime seed. This analysis is interesting since test particles cannot be in stable equilibrium for in a Schwarzschild spacetime, unlike thin shells (which renders them special and shows the importance of searching for distributional solutions in general relativity). In addition, it would allow us to probe thin shells in strong gravitational fields, as motivated by inner accretion discs in AGNs [24] or even in stratified neutron stars. In what follows, for numerical convenience, we take and , with , respectively. As expected, for two Schwarzschild spacetimes, when , all induced surface quantities are positive [1].

We must also choose other parameters related to the glued thin shells to proceed. Our analysis in Section 3 concluded that shells in equilibrium could be characterized by an arbitrary jump-free constant , related to the effective change of radius from R due to rotation. We chose for our investigations the case where . The reasons for that were mainly connected with its physical reasonableness. One can verify that the glue of two Kerr spacetimes at is such that, for reasonable n (such as ) and , one has that and , meaning that the resultant surface is flattened in the poles and stretched in the equator with respect to a sphere, as one expects physically when rotation takes place. Situations where are left to be investigated elsewhere.

As we have shown previously, the stability analyses of slowly rotating thin shells (around given radial positions) can be summarized by their spherically symmetric counterparts (see Section 3). Therefore, we should analyze the stability of glued Schwarzschild spacetimes to investigate slowly rotating Kerr spacetimes. It is known in this case that a thin shell is stable at iff its associated effective potential [1]:

has a minimum there (). It can be shown that [20]

where is defined as the adiabatic speed of sound squared on the shell [20], i.e., . We stress that, for the thin shell formalism to make sense, , which we took in our analysis. That also justified the perturbative treatment with respect to the spherically symmetric case in the previous sections.

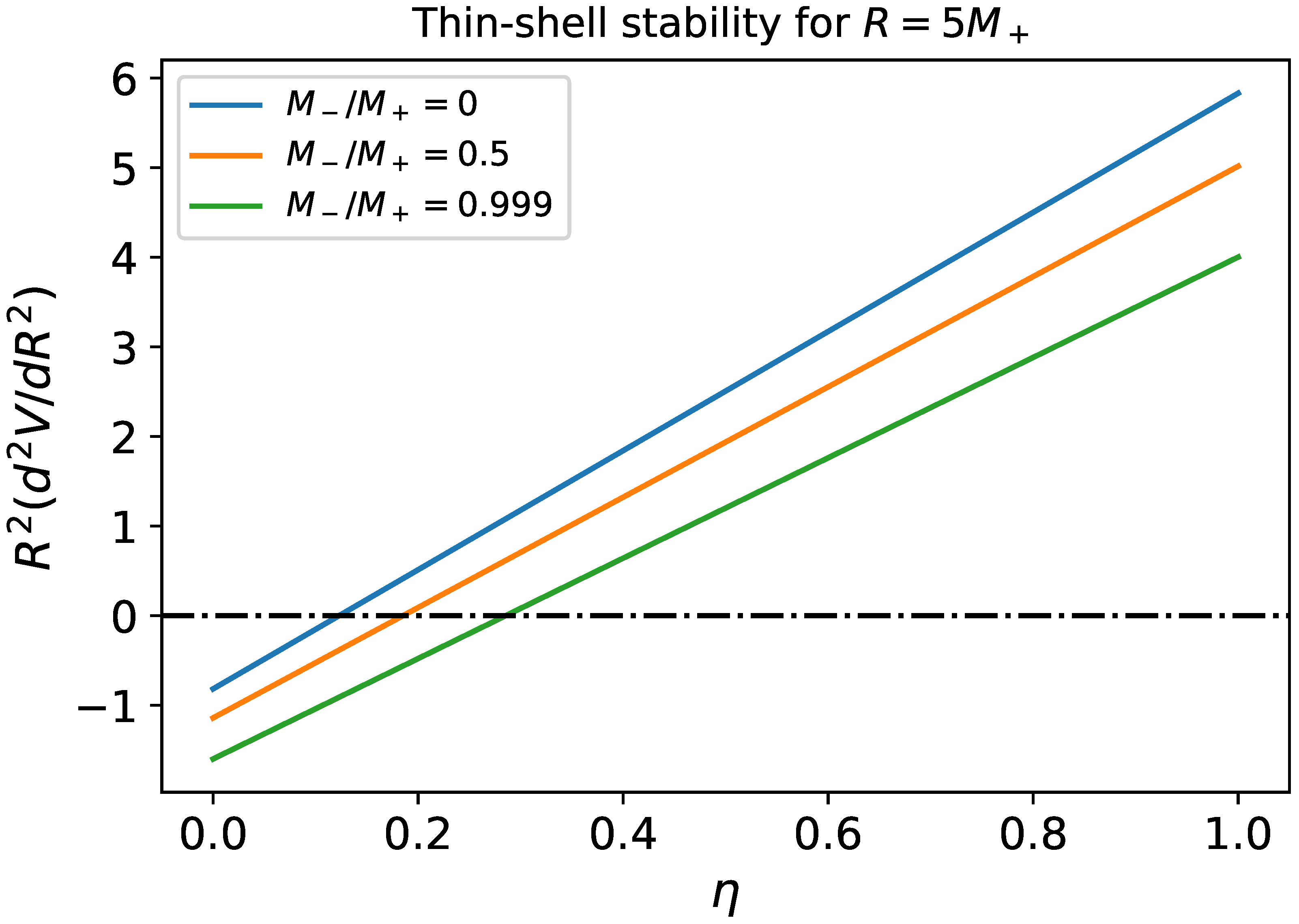

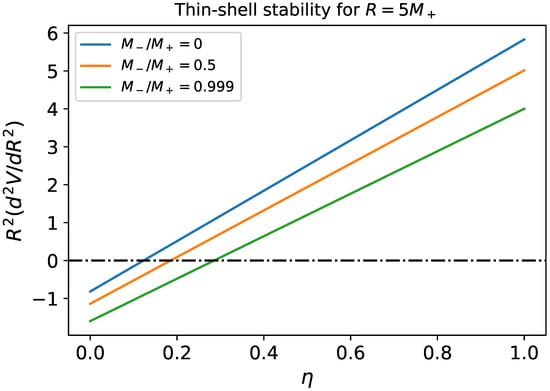

Figure 1 shows the stability condition () for several matches of Schwarzschild spacetimes with masses leading to at . One sees from the aforementioned plot that thin shells are stable for most and internal-to-external mass ratios. This suggests that is a feasible choice for the equilibrium radius of a thin shell with nontrivial surface degrees of freedom.

Figure 1.

Thin-shell stability for some glues of Schwarzschild spacetimes where the outer masses are always larger than the inner ones, leading to and . The equilibrium radius is taken as for all cases. For Schwarszchild spacetimes, the quantity of relevance is , and could be any. In particular, when , several thin shells’ speed of sound lead to stable equilibria. That is the case even for very small thin-shell masses (). For the case , any will fulfill the stability condition.

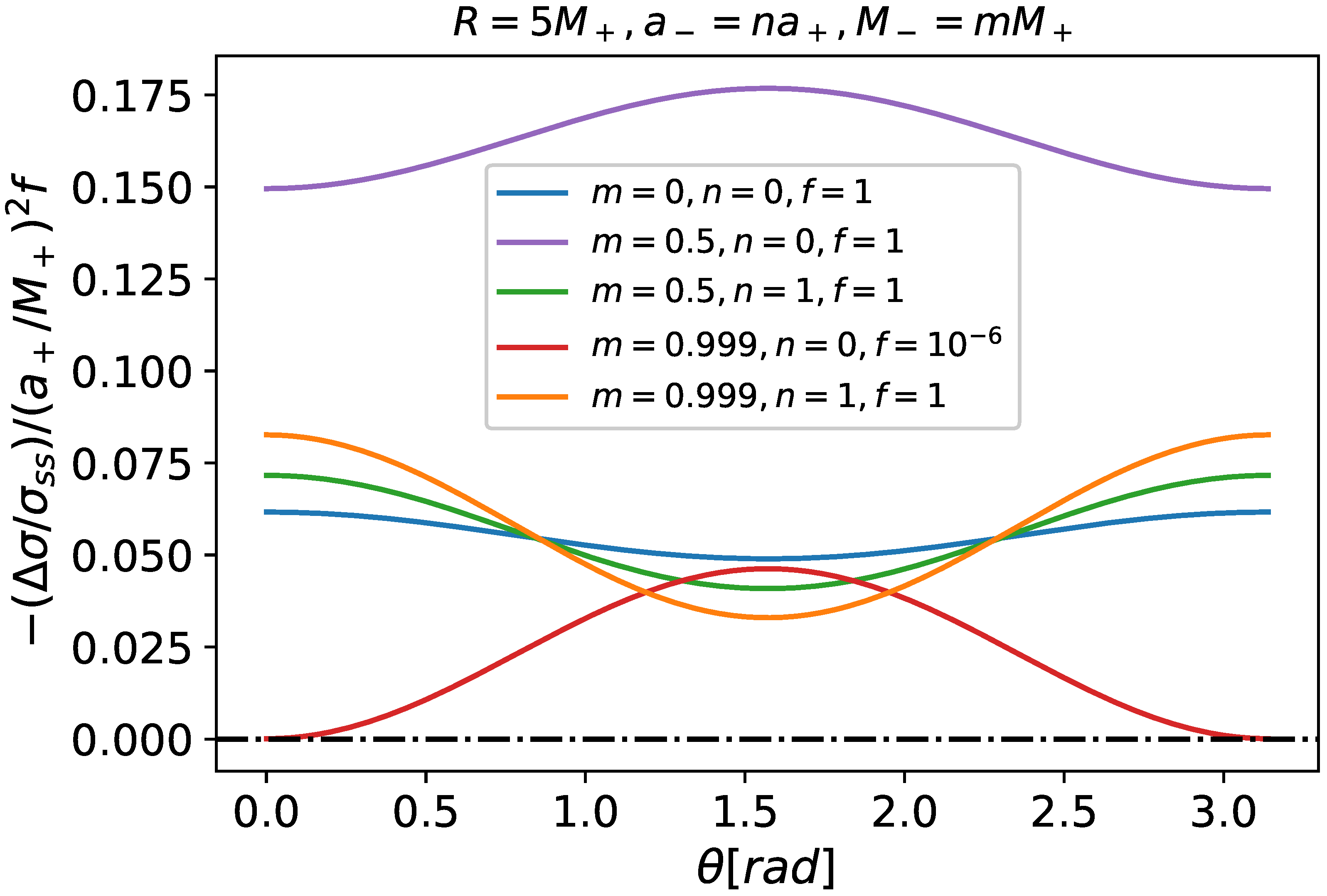

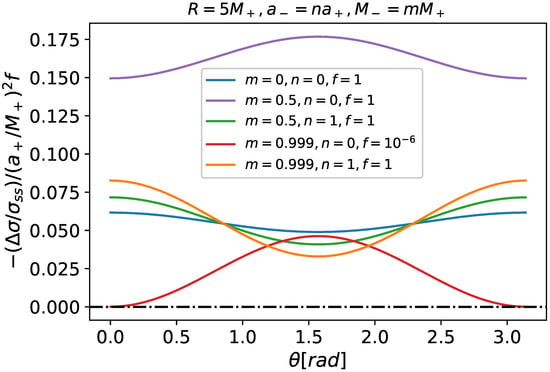

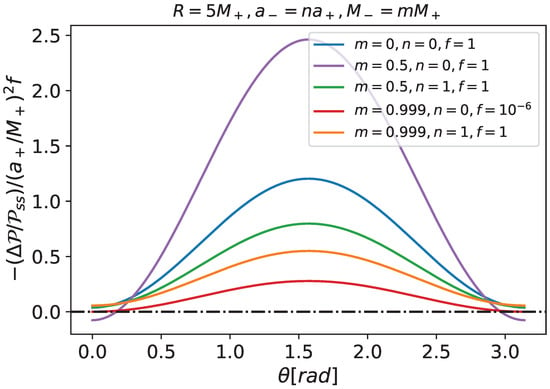

We studied induced surface quantities on slowly rotating neutral thin shells in slowly rotating Kerr spacetimes. Figure 2 shows the relative changes for the surface energy densities () for some selected Schwarzschild seeds. For all polar angles, they decrease when compared to their spherically symmetric counterparts. That is the case if the inner spacetime counter-rotates with respect to the outer one (because ’s with positive and negative n do not differ much), if it has no rotation at all () or if it has the same rotation as the external one (). That is the same concerning relative changes of the relative surface tension (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Relative surface energy density corrections due to rotation () for some parameters of the glued spacetimes. Internal and external mass ratios were chosen to coincide with those of Figure 2. To be more general, we did not specify the particular rotational parameter ; we just assumed it was small. The factor “f” is only for convenience (plotting all the cases in a similar scale). Negative n’s lead to the same results as their positive counterparts. Note that, for all the cases and polar angles, , meaning that rotation decreases the local surface energy density on the thin shell.

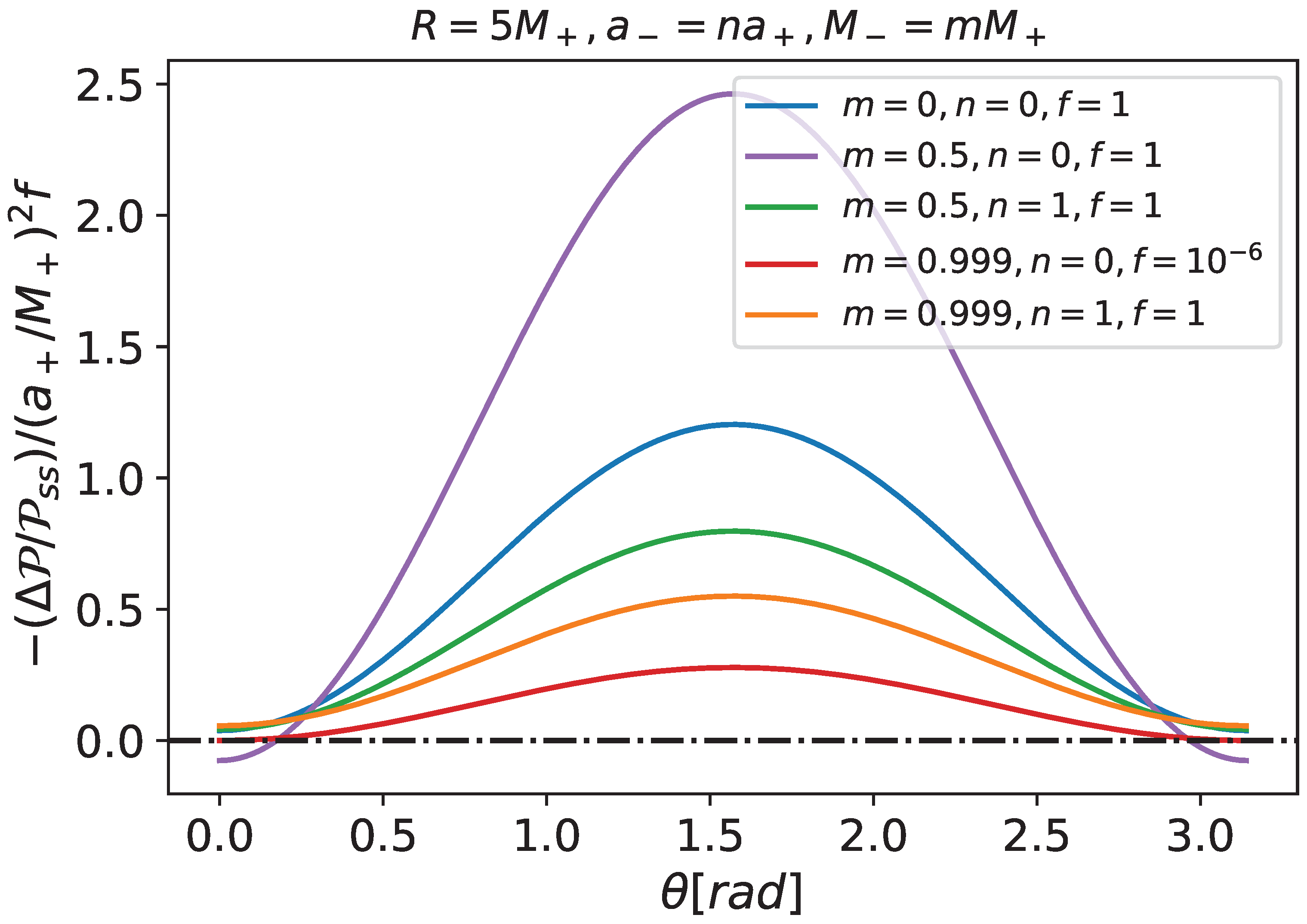

Figure 3.

Relative induced surface tension () as a function of the polar angle . We chose the same mass ratios of Figure 2. Note that, for almost all choices of thin-shell mass and polar angles, the surface tension correction to the spherically symmetric case due to rotation is negative.

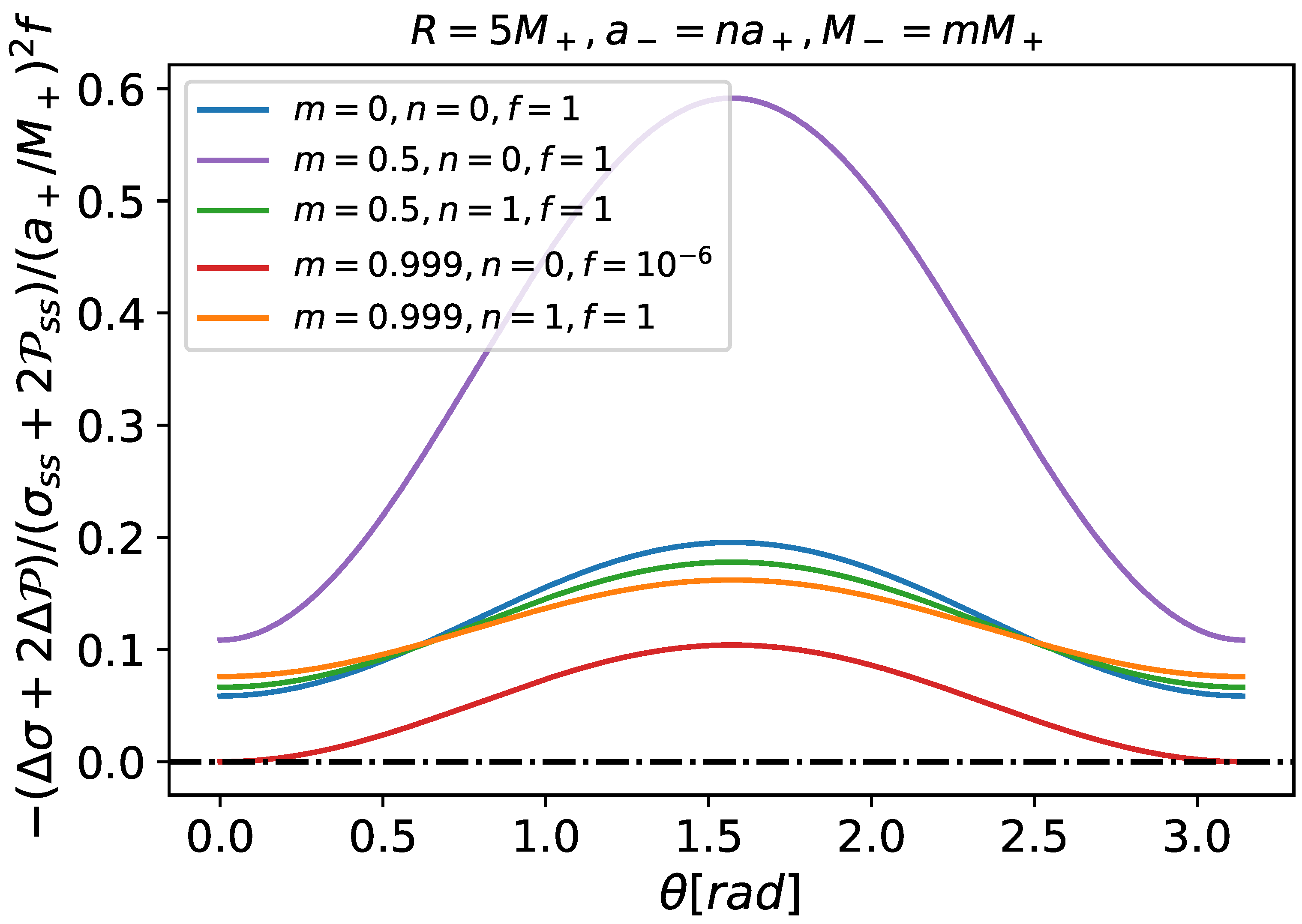

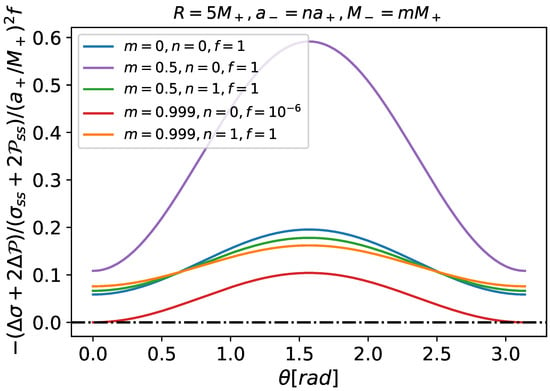

For all the cases in Figure 1, it is simple to verify that the weak, null, strong, and dominant energy conditions [18] are satisfied. This shows the reasonableness of our assumptions. In the presence of rotation, the aforesaid conditions are slightly weakened. Figure 4 exemplifies the previous statement due to the negativity of the induced part of the strong energy condition () for the spacetime matches in Figure 1. Similar conclusions could be reached for the weakening of other energy conditions (weak and null) because both and are negative. Naturally, in the perturbative scope, this does not mean any violation of the energy conditions, but only their weakening when small rotations are present, which suggests nontrivial behavior in the non-perturbative case.

Figure 4.

The parameters for the curves are the same as their counterparts in Figure 2. The induced part due to the rotation in the strong energy condition () is negative (clearly not the case for the selected values of the glued spacetimes, whose spherically symmetric counterparts satisfy all energy conditions), which points to the possibility of the non-validity of some energy conditions in non-perturbative analyses.

7. Concluding Remarks

This work showed the subtleties and nontrivialities in matching two slowly rotating Hartle’s spacetimes through dynamic hypersurfaces. For a given matching hypersurface, we obtained generically that its equilibrium points are stable if their spherically symmetric counterparts are so. Concerning the kinematical effects, we showed that it is possible to match spacetimes where a rigid-rotation behavior appears—at least in some limit—and the frame-dragging effect can give information about the matched spacetimes. We also found that the thin shells’ surface energy densities and surface tensions decrease compared to their spherical counterparts. This suggests, for instance, that the assumption of having everywhere-positive surface degrees of freedom may be broken in non-perturbative calculations. Energy conditions may also be violated in this scenario, which could have important consequences (for the relevance of the energy conditions in general relativity, see Chapter 34 of [21,25]). Another possibility would be that the possible violation of the energy conditions would preclude the existence of such thin-shell structures. Given its importance, we plan to investigate that better elsewhere.

Let us elaborate on some of the above points. The automatic stability of a slowly rotating thin shell, when its spherically symmetric seed is stable, is reasonable because a slowly rotating spacetime and thin shell perturbations there can be roughly seen as effective thin-shell perturbations in the spherical case. The fact that this stability emerges from our system of equations when matching two slowly rotating spacetimes is also relevant because it strengthens its consistency and it shows that, when the thin shell stability is concerned, it suffices to analyze just the spherically symmetric case. On the other hand, the decrease in the value of surface quantities when the slow rotation is present (as was clear when matching two Kerr spacetimes) is not trivial. A possible interpretation of it is that part of the thin-shell energy goes into rotational energy. That would reinforce the need, in general, to go beyond the slow rotation approximation we adopted. Clearly, this is not an easy task because some symmetries of the spacetimes to be matched are lost. However, it is worth mentioning that, for instance, in the case of rotating neutron stars, deviations from the spherical symmetry are essentially negligible for rotation rates of up to a few hundred Hz (see, e.g., [26,27]). Thus, we expect the slow-rotation Hartle spacetime metric to be a reasonable approximation for those configurations. Finally, Figure 3 and Figure 4 also show that the largest relative differences for the surface tension and surface energy density when m is not too close to unity happen when the internal spacetime is flat (i.e., Minkowski). The reason here is that this case leads to the largest mass–energy content of the thin shell. Thus, one would also expect that their relative differences would be maximized with respect to other cases where the internal spacetime has mass and rotation. The results for m close to one should be taken with a grain of salt because the perturbative model investigated breaks down when (no surface degrees of freedom are induced in the background spacetime).

One could apply the thin shell formalism developed here for cases involving astrophysical black holes, which are believed to be of the Kerr type. That could be for those at the centers of galaxies, such as AGNs, or even those in binaries or alone. The idea is that structures (thin shells) could be formed around black holes, wrapping them up totally or partially. For the case of black holes with masses ranging from one to two solar masses and thin shells with a (small) fraction of that mass, if their equilibrium position is –, then R is of the order of a neutron star’s radius (≈12 km for a star [28,29]). The intriguing question is whether external observers could perceive those thin shells as neutron stars. If, instead, BHs of around a solar mass are wrapped up by thin shells and equilibrium radii around –, one could perceive them as white dwarfs. In the era of gravitational-wave astronomy, these possibilities seem interesting to be better investigated because the above equilibrium radii are stable for a large range of sound speeds on the thin shells. Some gravitational-wave aspects are already known for some exotic compact objects (see, e.g., [9,11,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]).

Another special arena of application of this work is stratified compact stars, which have in their interiors a huge range of densities and pressures and even different matter phases (e.g., solid and liquid hadronic phases [38] or possibly even the quark and hadronic phases of hybrid stars [39]). Slow rotation would be the natural extension of the spherically symmetric case, where the stability formalism for stratified stars is already known [40] and surface degrees of freedom can be induced upon perturbations [41]. The approach presented here can be applied to the match of various matter phases since the second-order slow rotation approximation is accurate for the description of uniformly rotating neutron stars up to frequencies Hz (see, e.g., References [26,42]). In this line, comparing and contrasting the stability when a thin shell matches different phases for static and rotating configurations seem relevant. The formalism could also be applied if the surface of a neutron star is buried with a thin layer of supernova debris (e.g., as the so-called central compact objects (CCOs) [43,44,45]). In addition, one could check whether or not the stringent stability of strange quark stars with an outer crust obtained in [20] changes when adding rotation. The case of neutron stars rotating in the kHz region needs the non-perturbative solution of the match of axially symmetric spacetimes, which represents the ultimate goal of the analysis proposed in this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.P. and J.A.R.; numerical analysis, J.P.P.; formal analysis. J.P.P. and J.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.P. and J.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação do Estado do Espírito Santo (FAPES), Grant Number 04/2022.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jaziel G. Coelho for useful comments, which helped us improve the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lobo, F.S.N.; Crawford, P. Stability analysis of dynamic thin shells. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, 4869–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, P.; Lake, K. Junctions and thin shells in general relativity using computer algebra: I. The Darmois—Israel formalism. Class. Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, 1885–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, V.; Israel, W. Spinning Shell as a Source of the Kerr Metric. Phys. Rev. 1968, 170, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegeles, L.S. Collapse to a rotating black hole. Phys. Rev. D 1978, 18, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchikata, N.; Yoshida, S. Slowly rotating regular black holes with a charged thin shell. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 064042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, H.; Braun, K.H. A mass shell with flat interior cannot rotate rigidly. Class. Quantum Gravity 1986, 3, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwig, L.P. Machian effects in compact, rapidly spinning shells. Phys. Rev. D 1978, 18, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.F.P.; Matsas, G.E.A.; Vanzella, D.A.T. Instability of nonminimally coupled scalar fields in the spacetime of slowly rotating compact objects. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 044053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, P. I-Love-Q relations for gravastars and the approach to the black-hole limit. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 124030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchikata, N.; Yoshida, S. Slowly rotating thin shell gravastars. Class. Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchikata, N.; Yoshida, S.; Pani, P. Tidal deformability and I-Love-Q relations for gravastars with polytropic thin shells. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 064015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltracchi, P.; Gondolo, P.; Mottola, E. Slowly rotating gravastars. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 105, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.S.; Mishra, B.; Tello-Ortiz, F.; Alvarez, A. f(R)f(R) Wormholes Embedded in a Pseudo–Euclidean Space E 5. Fortschritte Der Phys. 2022, 70, 2100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello-Ortiz, F.; Mishra, B.; Alvarez, A.; Singh, K.N. Minimally Deformed Wormholes Inspired by Noncommutative Geometry. Fortschritte Der Phys. 2023, 71, 2200108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J.B. Slowly Rotating Relativistic Stars. I. Equations of Structure. Astrophys. J. 1967, 150, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanczos, K. Flächenhafte Verteilung der Materie in der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie. Ann. Der Phys. 1924, 379, 518–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, W. Singular hypersurfaces and thin shells in general relativity. Nuovo C. B Ser. 1966, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, E. A Relativist’s Toolkit: The Mathematics of Black-Hole Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eiroa, E.F.; Simeone, C. Stability of charged thin shells. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.P.; Coelho, J.G.; Rueda, J.A. Stability of thin-shell interfaces inside compact stars. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 123011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; W.H. Freeman and Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, C.W.F.; Debra, D.B.; Parkinson, B.W.; Turneaure, J.P.; Conklin, J.W.; Heifetz, M.I.; Keiser, G.M.; Silbergleit, A.S.; Holmes, T.; Kolodziejczak, J.; et al. Gravity Probe B: Final Results of a Space Experiment to Test General Relativity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 221101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman Krishnan, V.; Bailes, M.; van Straten, W.; Wex, N.; Freire, P.C.C.; Keane, E.F.; Tauris, T.M.; Rosado, P.A.; Bhat, N.D.R.; Flynn, C.; et al. Lense-Thirring frame dragging induced by a fast-rotating white dwarf in a binary pulsar system. Science 2020, 367, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, A.C.; Wilkins, D.R.; Miller, J.M.; Reis, R.C.; Reynolds, C.S.; Cackett, E.M.; Nowak, M.A.; Pooley, G.G.; Pottschmidt, K.; Sanders, J.S.; et al. On the determination of the spin of the black hole in Cyg X-1 from X-ray reflection spectra. MNRAS 2012, 424, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontou, E.A.; Sanders, K. Energy conditions in general relativity and quantum field theory. Class. Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvedere, R.; Boshkayev, K.; Rueda, J.A.; Ruffini, R. Uniformly rotating neutron stars in the global and local charge neutrality cases. Nucl. Phys. A 2014, 921, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, F.; Cherubini, C.; Filippi, S.; Rueda, J.A.; Ruffini, R. Fast rotating neutron stars with realistic nuclear matter equation of state. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 023007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.E.; Watts, A.L.; Bogdanov, S.; Ray, P.S.; Ludlam, R.M.; Guillot, S.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Baker, C.L.; Bilous, A.V.; Chakrabarty, D.; et al. A NICER View of PSR J0030+0451: Millisecond Pulsar Parameter Estimation. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 887, L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.C.; Lamb, F.K.; Dittmann, A.J.; Bogdanov, S.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Gendreau, K.C.; Guillot, S.; Harding, A.K.; Ho, W.C.G.; Lattimer, J.M.; et al. PSR J0030+0451 Mass and Radius from NICER Data and Implications for the Properties of Neutron Star Matter. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 887, L24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, A.; Pnigouras, P.; Nielsen, N.G.; Kouvaris, C.; Kokkotas, K.D. Dark stars: Gravitational and electromagnetic observables. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 023005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.; Franzin, E.; Maselli, A.; Pani, P.; Raposo, G. Testing strong-field gravity with tidal Love numbers. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 084014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Pani, P.; Emparan, R. Exotic compact objects with soft hair. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 99, 104050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, A.; Pani, P.; Cardoso, V.; Abdelsalhin, T.; Gualtieri, L.; Ferrari, V. Probing Planckian Corrections at the Horizon Scale with LISA Binaries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 081101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, V.; Pani, P. Testing the nature of dark compact objects: A status report. Living Rev. Relativ. 2019, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-McDaniel, N.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Kashyap, R.; Ajith, P.; Del Pozzo, W.; Vitale, S. Constraining black hole mimickers with gravitational wave observations. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 123010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narikawa, T.; Uchikata, N.; Tanaka, T. Gravitational-wave constraints on the GWTC-2 events by measuring the tidal deformability and the spin-induced quadrupole moment. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 104, 084056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, E.; Pani, P.; Raposo, G. Testing the Nature of Dark Compact Objects with Gravitational Waves. In Handbook of Gravitational Wave Astronomy; Springer: Singapore, 2021; p. 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haensel, P.; Potekhin, A.Y.; Yakovlev, D.G. Neutron Stars 1: Equation of State and Structure; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 326, pp. 1–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.P.; Flores, C.V.; Lugones, G. Phase Transition Effects on the Dynamical Stability of Hybrid Neutron Stars. Astrophys. J. 2018, 860, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.P.; Rueda, J.A. Radial Stability in Stratified Stars. Astrophys. J. 2015, 801, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.P.; Lugones, G. General Relativistic Surface Degrees of Freedom in Perturbed Hybrid Stars. Astrophys. J. 2019, 871, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhar, O.; Ferrari, V.; Gualtieri, L.; Marassi, S. Perturbative approach to the structure of rapidly rotating neutron stars. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 044028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.C.G. Evolution of a buried magnetic field in the central compact object neutron stars. MNRAS 2011, 414, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganò, D.; Pons, J.A. Central compact objects and the hidden magnetic field scenario. MNRAS 2012, 425, 2487–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A. Central compact objects in supernova remnants. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 932, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).