Amylin and Secretases in the Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

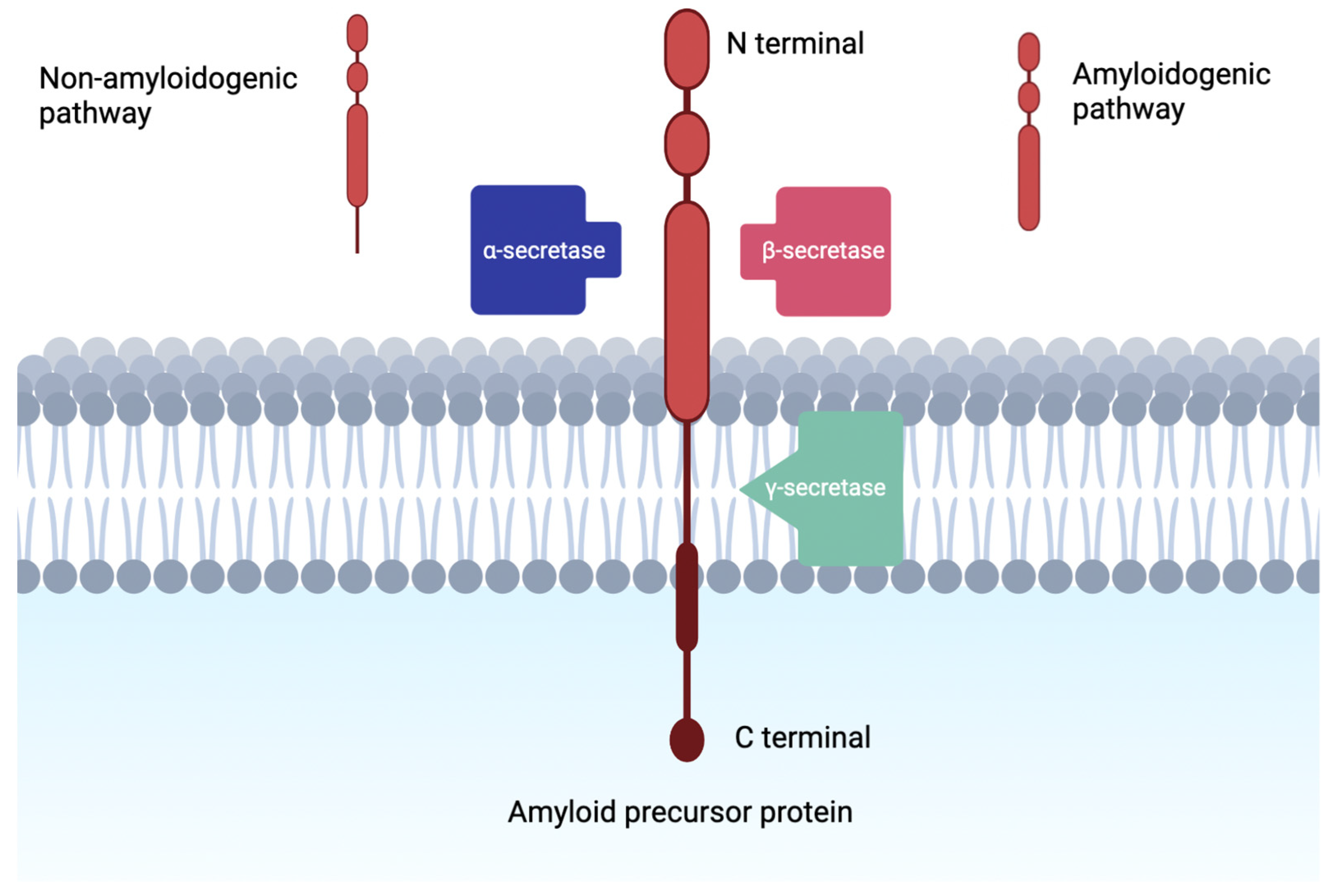

1.1. Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis

1.2. Small Peptide Synthetic Therapy in Neurodegenerative Disease

2. Alpha Secretase Activators

3. Beta-Secretase Inhibitors

4. Gamma-Secretase Inhibitors

5. Amylin Agonists

6. Discussion

| Biomolecule | Therapeutic Mechanism | Synthetic Subtypes under Investigation | Status of Investigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-secretase | Activation | ADAM10 ADAM17 Gemfibrozil | Gemfibrozil Phase I Trial—2019 [110,111] Acitretin Phase II Trial—2018 [112] APH-1105 Phase II Trial—2021 [113] Epigallocatechin-Gallate Phase III—2021 [114] |

| β-secretase | Inhibition | BACE1 LY-2886721 | AZD3293 Phase I Trial—2014 [115] LY-2886721 Phase II Trial—2018 [116] JNJ-54861911 Phase II Trial—2022 [117,118] CNP520 Phase II Trial [119] Verubecestat Phase III Trial—2019 [120] |

| γ-secretase | Inhibition | LY-450139 E2012 PF-308414 | LY-450139 Phase III Trial—2019 [121] Semagacestat Phase III Trial—2014 [122] Avagacestat Phase II Trial—2015 [123] GSI-136 Phase I Trial—2010 [124] NGP-555 Phase I Trial—2016 [125] |

| Amylin | Agonist | Pramlintide acetate Exenatide | Exendin-4 Phase II Trial—2018 [126] |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dumurgier, J.; Sabia, S. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: Latest trends. Rev. Prat. 2020, 70, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.-T.; Ma, Y.-H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. The Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 8, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermunt, L.; Sikkes, S.A.M.; van den Hout, A.; Handels, R.; Bos, I.; van der Flier, W.M.; Kern, S.; Ousset, P.-J.; Maruff, P.; Skoog, I.; et al. Duration of Preclinical, Prodromal, and Dementia Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease in Relation to Age, Sex, and APOE Genotype. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2019, 15, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, B.; Hampel, H.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P.; Aisen, P.; Andrieu, S.; Bakardjian, H.; Benali, H.; Bertram, L.; Blennow, K.; et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease: Definition, Natural History, and Diagnostic Criteria. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2016, 12, 292–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W.J.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Knol, D.L.; Tijms, B.M.; Scheltens, P.; Verhey, F.R.J.; Visser, P.J.; Amyloid Biomarker Study Group; Aalten, P.; Aarsland, D.; et al. Prevalence of Cerebral Amyloid Pathology in Persons without Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 1924–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Sorbi, S. The Complexity of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Evolving Puzzle. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1047–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Gauthier, S.; Corbett, A.; Brayne, C.; Aarsland, D.; Jones, E. Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2011, 377, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karran, E.; Mercken, M.; Strooper, B.D. The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis for Alzheimer’s Disease: An Appraisal for the Development of Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacca, M.F.M.; Tempra, C.; Scollo, F.; Milardi, D.; La Rosa, C. Amyloid Growth and Membrane Damage: Current Themes and Emerging Perspectives from Theory and Experiments on Aβ and HIAPP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Allsop, D. Amyloid Deposition as the Central Event in the Aetiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991, 12, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, M.; Tacal, O. Trafficking and Proteolytic Processing of Amyloid Precursor Protein and Secretases in Alzheimer’s Disease Development: An up-to-Date Review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 856, 172415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamayev, R.; Matsuda, S.; Arancio, O.; D’Adamio, L. β- but Not γ-Secretase Proteolysis of APP Causes Synaptic and Memory Deficits in a Mouse Model of Dementia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012, 4, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paroni, G.; Bisceglia, P.; Seripa, D. Understanding the Amyloid Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2019, 68, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, H.C.; de Malmazet, D.; Schreurs, A.; Frere, S.; Van Molle, I.; Volkov, A.N.; Creemers, E.; Vertkin, I.; Nys, J.; Ranaivoson, F.M.; et al. Secreted Amyloid-β Precursor Protein Functions as a GABABR1a Ligand to Modulate Synaptic Transmission. Science 2019, 363, eaao4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, D.; Barbour, R.; Dunn, W.; Gordon, G.; Grajeda, H.; Guido, T.; Hu, K.; Huang, J.; Johnson-Wood, K.; Khan, K.; et al. Immunization with Amyloid-Beta Attenuates Alzheimer-Disease-like Pathology in the PDAPP Mouse. Nature 1999, 400, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, R.J.; Knopman, D.S.; Bu, G. An Agnostic Reevaluation of the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis: The Role of APP Homeostasis. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2020, 16, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolar, M.; Abushakra, S.; Sabbagh, M. The Path Forward in Alzheimer’s Disease Therapeutics: Reevaluating the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2020, 16, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.F. Overview of Neuropeptides: Awakening the Senses? Headache 2017, 57 (Suppl. 2), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Katz, L.C.; LaMantia, A.-S.; McNamara, J.O.; Williams, S.M. Peptide Neurotransmitters. In Neuroscience, 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Massachusetts, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Pandey, D.; Ashraf, G.M. Rachana, null Peptide Based Therapy for Neurological Disorders. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2021, 22, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsley, J.R.; Jovcevski, B.; Wegener, K.L.; Yu, J.; Pukala, T.L.; Abell, A.D. Rationally Designed Peptide-Based Inhibitor of Aβ42 Fibril Formation and Toxicity: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aillaud, I.; Kaniyappan, S.; Chandupatla, R.R.; Ramirez, L.M.; Alkhashrom, S.; Eichler, J.; Horn, A.H.C.; Zweckstetter, M.; Mandelkow, E.; Sticht, H.; et al. A Novel D-Amino Acid Peptide with Therapeutic Potential (ISAD1) Inhibits Aggregation of Neurotoxic Disease-Relevant Mutant Tau and Prevents Tau Toxicity in Vitro. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaraju, S.; Gearing, M.; Jin, L.-W.; Levey, A. Potassium Channel Kv1.3 Is Highly Expressed by Microglia in Human Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2015, 44, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maezawa, I.; Nguyen, H.M.; Di Lucente, J.; Jenkins, D.P.; Singh, V.; Hilt, S.; Kim, K.; Rangaraju, S.; Levey, A.I.; Wulff, H.; et al. Kv1.3 Inhibition as a Potential Microglia-Targeted Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: Preclinical Proof of Concept. Brain J. Neurol. 2018, 141, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Strooper, B.; Vassar, R.; Golde, T. The Secretases: Enzymes with Therapeutic Potential in Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacLeod, R.; Hillert, E.-K.; Cameron, R.T.; Baillie, G.S. The Role and Therapeutic Targeting of α-, β- and γ-Secretase in Alzheimer’s Disease. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishiura, S.; Asai, M.; Hattori, C.; Hotoda, N.; Szabo, B.; Sasagawa, N.; Tanuma, S. APP α-Secretase, a Novel Target for Alzheimer Drug Therapy; Landes Bioscience: Austin, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saftig, P.; Lichtenthaler, S.F. The Alpha Secretase ADAM10: A Metalloprotease with Multiple Functions in the Brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 135, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.; May, P.; Gu, W.; Mayhaus, M.; Pichler, S.; Spaniol, C.; Glaab, E.; Bobbili, D.R.; Antony, P.; Koegelsberger, S.; et al. A Rare Loss-of-Function Variant of ADAM17 Is Associated with Late-Onset Familial Alzheimer Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, R.; Vatanabe, I.P.; Manzine, P.R.; Camins, A.; Cominetti, M.R. Alpha-Secretase ADAM10 Regulation: Insights into Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2018, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Remington, R.; Bechtel, C.; Larsen, D.; Samar, A.; Page, R.; Morrell, C.; Shea, T.B. Maintenance of Cognitive Performance and Mood for Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease Following Consumption of a Nutraceutical Formulation: A One-Year, Open-Label Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2016, 51, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Pahan, K. Gemfibrozil, a Lipid-Lowering Drug, Lowers Amyloid Plaque Pathology and Enhances Memory in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease via Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2019, 3, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forner, S.; Kawauchi, S.; Balderrama-Gutierrez, G.; Kramár, E.A.; Matheos, D.P.; Phan, J.; Javonillo, D.I.; Tran, K.M.; Hingco, E.; da Cunha, C.; et al. Systematic Phenotyping and Characterization of the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.J.; Son, Y.; Park, H.-J.; Oh, S.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Ko, Y.-G.; Lee, H.-J. Therapeutic Effects of Aripiprazole in the 5xFAD Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblak, A.L.; Lin, P.B.; Kotredes, K.P.; Pandey, R.S.; Garceau, D.; Williams, H.M.; Uyar, A.; O’Rourke, R.; O’Rourke, S.; Ingraham, C.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the 5XFAD Mouse Model for Preclinical Testing Applications: A MODEL-AD Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáez-Orellana, F.; Octave, J.-N.; Pierrot, N. Alzheimer’s Disease, a Lipid Story: Involvement of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α. Cells 2020, 9, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metabolic and Cerebrovascular Effects of Gemfibrozil Treatment: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind, Phase II Clinical Trial for Dementia Prevention—Jicha—2021—Alzheimer’s & Dementia—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/alz.055777 (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Yang, H.-Q.; Sun, Z.-K.; Ba, M.-W.; Xu, J.; Xing, Y. Involvement of Protein Trafficking in Deprenyl-Induced Alpha-Secretase Activity Regulation in PC12 Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 610, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, S.; Ehrlich, M.; Pedrini, S.; Diaz, N.; Refolo, L.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Bogush, A.; Petanceska, S.; Gandy, S. Atorvastatin-Induced Activation of Alzheimer’s Alpha Secretase Is Resistant to Standard Inhibitors of Protein Phosphorylation-Regulated Ectodomain Shedding. J. Neurochem. 2004, 90, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogorb-Esteve, A.; García-Ayllón, M.-S.; Gobom, J.; Alom, J.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Sáez-Valero, J. Levels of ADAM10 Are Reduced in Alzheimer’s Disease CSF. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, P.; Sandonìs, A.; Cardozo, M.; Malapeira, J.; Ibañez, C.; Crespo, I.; Marcos, S.; Gonzalez-Garcia, S.; Toribio, M.L.; Arribas, J.; et al. SFRPs Act as Negative Modulators of ADAM10 to Regulate Retinal Neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, B.L. Enhancing α-Secretase Processing for Alzheimer’s Disease-A View on SFRP1. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteve, P.; Rueda-Carrasco, J.; Inés Mateo, M.; Martin-Bermejo, M.J.; Draffin, J.; Pereyra, G.; Sandonís, Á.; Crespo, I.; Moreno, I.; Aso, E.; et al. Elevated Levels of Secreted-Frizzled-Related-Protein 1 Contribute to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Tosaki, A.; Kaneko, K.; Hisano, T.; Sakurai, T.; Nukina, N. Crystal Structure of an Active Form of BACE1, an Enzyme Responsible for Amyloid β Protein Production. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 3663–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, X.; Koelsch, G.; Wu, S.; Downs, D.; Dashti, A.; Tang, J. Human Aspartic Protease Memapsin 2 Cleaves the Beta-Secretase Site of Beta-Amyloid Precursor Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Greenblatt, H.; Chen, W.; Paz, A.; Dym, O.; Peleg, Y.; Chen, T.; Shen, X.; He, J.; et al. Flexibility of the Flap in the Active Site of BACE1 as Revealed by Crystal Structures and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012, 68, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, T.; Atwal, J.K.; Steinberg, S.; Snaedal, J.; Jonsson, P.V.; Bjornsson, S.; Stefansson, H.; Sulem, P.; Gudbjartsson, D.; Maloney, J.; et al. A Mutation in APP Protects against Alzheimer’s Disease and Age-Related Cognitive Decline. Nature 2012, 488, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Sametsky, E.A.; Younkin, L.H.; Oakley, H.; Younkin, S.G.; Citron, M.; Vassar, R.; Disterhoft, J.F. BACE1 Deficiency Rescues Memory Deficits and Cholinergic Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2004, 41, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheret, C.; Willem, M.; Fricker, F.R.; Wende, H.; Wulf-Goldenberg, A.; Tahirovic, S.; Nave, K.-A.; Saftig, P.; Haass, C.; Garratt, A.N.; et al. Bace1 and Neuregulin-1 Cooperate to Control Formation and Maintenance of Muscle Spindles. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voytyuk, I.; Mueller, S.A.; Herber, J.; Snellinx, A.; Moechars, D.; van Loo, G.; Lichtenthaler, S.F.; De Strooper, B. BACE2 Distribution in Major Brain Cell Types and Identification of Novel Substrates. Life Sci. Alliance 2018, 1, e201800026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Brindisi, M.; Yen, Y.-C.; Lendy, E.K.; Kovela, S.; Cárdenas, E.L.; Reddy, B.S.; Rao, K.V.; Downs, D.; Huang, X.; et al. Highly Selective and Potent Human β-Secretase 2 (BACE2) Inhibitors against Type 2 Diabetes: Design, Synthesis, X-Ray Structure and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Cai, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Song, W. BACE2, a Conditional β-Secretase, Contributes to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 123431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dominguez, D.; Tournoy, J.; Hartmann, D.; Huth, T.; Cryns, K.; Deforce, S.; Serneels, L.; Camacho, I.E.; Marjaux, E.; Craessaerts, K.; et al. Phenotypic and Biochemical Analyses of BACE1- and BACE2-Deficient Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30797–30806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huentelman, M.; De Both, M.; Jepsen, W.; Piras, I.S.; Talboom, J.S.; Willeman, M.; Reiman, E.M.; Hardy, J.; Myers, A.J. Common BACE2 Polymorphisms Are Associated with Altered Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease and CSF Amyloid Biomarkers in APOE Ε4 Non-Carriers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, X.; He, G.; Song, W. BACE2, as a Novel APP Theta-Secretase, Is Not Responsible for the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease in Down Syndrome. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2006, 20, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassar, R. BACE1 Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, B.; Yan, R. A Close Look at BACE1 Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menting, K.W.; Claassen, J.A.H.R. β-Secretase Inhibitor; a Promising Novel Therapeutic Drug in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Brindisi, M.; Tang, J. Developing β-Secretase Inhibitors for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Shin, D.; Downs, D.; Koelsch, G.; Lin, X.; Ermolieff, J.; Tang, J. Design of Potent Inhibitors for Human Brain Memapsin 2 (β-Secretase). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3522–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Igawa, N.; Ikari, H.; Ziora, Z.; Nguyen, J.-T.; Yamani, A.; Hidaka, K.; Kimura, T.; Saito, K.; Hayashi, Y.; et al. Beta-Secretase Inhibitors: Modification at the P4 Position and Improvement of Inhibitory Activity in Cultured Cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4354–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yan, R. Inhibition of BACE1 for Therapeutic Use in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2010, 3, 618–628. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M.E.; Stamford, A.W.; Chen, X.; Cox, K.; Cumming, J.N.; Dockendorf, M.F.; Egan, M.; Ereshefsky, L.; Hodgson, R.A.; Hyde, L.A.; et al. The BACE1 Inhibitor Verubecestat (MK-8931) Reduces CNS β-Amyloid in Animal Models and in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 363ra150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, M.A.; Sousa, E. BACE-1 and γ-Secretase as Therapeutic Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Egan, M.F.; Mukai, Y.; Voss, T.; Kost, J.; Stone, J.; Furtek, C.; Mahoney, E.; Cummings, J.L.; Tariot, P.N.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. Further Analyses of the Safety of Verubecestat in the Phase 3 EPOCH Trial of Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, P.C.; Willis, B.A.; Lowe, S.L.; Dean, R.A.; Monk, S.A.; Cocke, P.J.; Audia, J.E.; Boggs, L.N.; Borders, A.R.; Brier, R.A.; et al. The Potent BACE1 Inhibitor LY2886721 Elicits Robust Central Aβ Pharmacodynamic Responses in Mice, Dogs, and Humans. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Satir, T.M.; Agholme, L.; Karlsson, A.; Karlsson, M.; Karila, P.; Illes, S.; Bergström, P.; Zetterberg, H. Partial Reduction of Amyloid β Production by β-Secretase Inhibitors Does Not Decrease Synaptic Transmission. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleffman, K.; Levinson, G.; Rose, I.V.L.; Blumenberg, L.M.; Shadaloey, S.A.A.; Dhabaria, A.; Wong, E.; Galán-Echevarría, F.; Karz, A.; Argibay, D.; et al. Melanoma-Secreted Amyloid Beta Suppresses Neuroinflammation and Promotes Brain Metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 1314–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golde, T.E.; Koo, E.H.; Felsenstein, K.M.; Osborne, B.A.; Miele, L. γ-Secretase Inhibitors and Modulators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 2898–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panza, F.; Frisardi, V.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Capurso, C.; Logroscino, G.; Sancarlo, D.; Seripa, D.; Vendemiale, G.; Pilotto, A.; Solfrizzi, V. REVIEW: Γ-Secretase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Current State. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2010, 16, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.S. Inhibition and Modulation of γ-Secretase for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleó, A.; Berezovska, O.; Growdon, J.H.; Hyman, B.T. Clinical, Pathological, and Biochemical Spectrum of Alzheimer Disease Associated with PS-1 Mutations. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentahir, M.; Nyabi, O.; Verhamme, J.; Tolia, A.; Horré, K.; Wiltfang, J.; Esselmann, H.; De Strooper, B. Presenilin Clinical Mutations Can Affect Gamma-Secretase Activity by Different Mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasugi, N.; Tomita, T.; Hayashi, I.; Tsuruoka, M.; Niimura, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Thinakaran, G.; Iwatsubo, T. The Role of Presenilin Cofactors in the γ-Secretase Complex. Nature 2003, 422, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Ji, S. Secretases Related to Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing. Membranes 2021, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Meyer, H.E.; Egensperger, R.; Marcus, K. The Amyloid Precursor Protein Intracellular Domain (AICD) as Modulator of Gene Expression, Apoptosis, and Cytoskeletal Dynamics-Relevance for Alzheimer’s Disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008, 85, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaether, C.; Schmitt, S.; Willem, M.; Haass, C. Amyloid Precursor Protein and Notch Intracellular Domains Are Generated after Transport of Their Precursors to the Cell Surface. Traffic Cph. Den. 2006, 7, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marambaud, P.; Wen, P.H.; Dutt, A.; Shioi, J.; Takashima, A.; Siman, R.; Robakis, N.K. A CBP Binding Transcriptional Repressor Produced by the PS1/Epsilon-Cleavage of N-Cadherin Is Inhibited by PS1 FAD Mutations. Cell 2003, 114, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Strooper, B.; Annaert, W.; Cupers, P.; Saftig, P.; Craessaerts, K.; Mumm, J.S.; Schroeter, E.H.; Schrijvers, V.; Wolfe, M.S.; Ray, W.J.; et al. A Presenilin-1-Dependent Gamma-Secretase-like Protease Mediates Release of Notch Intracellular Domain. Nature 1999, 398, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.Y.; Murphy, M.P.; Golde, T.E.; Carpenter, G. Gamma -Secretase Cleavage and Nuclear Localization of ErbB-4 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase. Science 2001, 294, 2179–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, R.S.; Raman, R.; Farlow, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Vellas, B.; Joffe, S.; Kieburtz, K.; He, F.; Sun, X.; Thomas, R.G.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Semagacestat for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, T.; Fuhrmann, M.; Burgold, S.; Jung, C.K.E.; Volbracht, C.; Steiner, H.; Mitteregger, G.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; Haass, C.; Herms, J. γ-Secretase Inhibition Reduces Spine Density In Vivo via an Amyloid Precursor Protein-Dependent Pathway. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10405–10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bateman, R.J.; Siemers, E.R.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Wen, G.; Browning, K.R.; Sigurdson, W.C.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Friedrich, S.W.; DeMattos, R.B.; May, P.C.; et al. A Gamma-Secretase Inhibitor Decreases Amyloid-Beta Production in the Central Nervous System. Ann. Neurol. 2009, 66, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crump, C.J.; Castro, S.V.; Wang, F.; Pozdnyakov, N.; Ballard, T.E.; Sisodia, S.S.; Bales, K.R.; Johnson, D.S.; Li, Y.-M. BMS-708,163 Targets Presenilin and Lacks Notch-Sparing Activity. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 7209–7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ran, Y.; Hossain, F.; Pannuti, A.; Lessard, C.B.; Ladd, G.Z.; Jung, J.I.; Minter, L.M.; Osborne, B.A.; Miele, L.; Golde, T.E. γ-Secretase Inhibitors in Cancer Clinical Trials Are Pharmacologically and Functionally Distinct. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.-Y. γ-Secretase in Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermark, P.; Andersson, A.; Westermark, G.T. Islet Amyloid Polypeptide, Islet Amyloid, and Diabetes Mellitus. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 795–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, K.H.; O’Brien, T.D.; Jordan, K.; Westermark, P. Impaired Glucose Tolerance Is Associated with Increased Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP) Immunoreactivity in Pancreatic Beta Cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1989, 135, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jordan, K.; Murtaugh, M.P.; O’Brien, T.D.; Westermark, P.; Betsholtz, C.; Johnson, K.H. Canine IAPP CDNA Sequence Provides Important Clues Regarding Diabetogenesis and Amyloidogenesis in Type 2 Diabetes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 169, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietlicki-Baase, E.G. Amylin in Alzheimer’s Disease: Pathological Peptide or Potential Treatment? Neuropharmacology 2018, 136, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Patel, A.; Kimura, R.; Soudy, R.; Jhamandas, J.H. Amylin Receptor: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R.; MacTavish, D.; Yang, J.; Westaway, D.; Jhamandas, J.H. Pramlintide Antagonizes Beta Amyloid (Aβ)- and Human Amylin-Induced Depression of Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Wallack, M.; Li, H.; Carreras, I.; Dedeoglu, A.; Hur, J.-Y.; Zheng, H.; Li, H.; Fine, R.; et al. Intraperitoneal Injection of the Pancreatic Peptide Amylin Potently Reduces Behavioral Impairment and Brain Amyloid Pathology in Murine Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grizzanti, J.; Corrigan, R.; Casadesus, G. Neuroprotective Effects of Amylin Analogues on Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis and Cognition. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2018, 66, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, S.Z.; Badae, N.M.; Issa, Y.A. Effect of Amylin on Memory and Central Insulin Resistance in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 126, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.; Tian, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, J.B.; Mcparland, L.; Gan, Q.; Qiu, W.Q. Oral Amylin Treatment Reduces the Pathological Cascade of Alzheimer’s Disease in a Mouse Model. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2021, 36, 15333175211012868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Ruangkittisakul, A.; MacTavish, D.; Shi, J.Y.; Ballanyi, K.; Jhamandas, J.H. Amyloid β (Aβ) Peptide Directly Activates Amylin-3 Receptor Subtype by Triggering Multiple Intracellular Signaling Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 18820–18830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minatohara, K.; Akiyoshi, M.; Okuno, H. Role of Immediate-Early Genes in Synaptic Plasticity and Neuronal Ensembles Underlying the Memory Trace. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gandolfi, D.; Cerri, S.; Mapelli, J.; Polimeni, M.; Tritto, S.; Fuzzati-Armentero, M.-T.; Bigiani, A.; Blandini, F.; Mapelli, L.; D’Angelo, E. Activation of the CREB/c-Fos Pathway during Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in the Cerebellum Granular Layer. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.; Xue, X.; Wang, E.; Wallack, M.; Na, H.; Hooker, J.M.; Kowall, N.; Tao, Q.; Stein, T.D.; Wolozin, B.; et al. Amylin Receptor Ligands Reduce the Pathological Cascade of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropharmacology 2017, 119, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, C. Insights from Nature: A Review of Natural Compounds That Target Protein Misfolding in Vivo. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2021, 17, 327–406. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Behbahani, H.; Eriksdotter, M. Innovative Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease-With Focus on Biodelivery of NGF. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Makin, C.; Neumann, P.; Peschin, S.; Goldman, D. Modelling the Value of Innovative Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 2021, 24, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, T.-F.; Hsieh, C.-R. The Adoption of Pharmaceutical Innovation and Its Impact on the Treatment Costs for Alzheimer’s Disease in Taiwan. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2014, 17, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldman, D.P.; Fillit, H.; Neumann, P. Accelerating Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Innovations from the Research Pipeline to Patients. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2018, 14, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Cho, S.K.; Aliyev, E.R.; Mattke, S.; Suen, S.-C. How Much Value Would a Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease Offer? Cost-Effectiveness Thresholds for Pricing a Disease-Modifying Therapy. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2020, 17, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Aisen, P.S.; DuBois, B.; Frölich, L.; Jack, C.R.; Jones, R.W.; Morris, J.C.; Raskin, J.; Dowsett, S.A.; Scheltens, P. Drug Development in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Path to 2025. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2016, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jicha, G. Modulation of Micro-RNA Pathways by Gemfibrozil in Predementia Alzheimer Disease. 2019; pp. 323–5550. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Wyeth is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Pfizer an Open-Label, Nonrandomized Study To Evaluate The Potential Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between SAM-531 and Gemfibrozil, A Cytochrome P-450 2C8 Inhibitor, When Coadministered Orally To Healthy Young Adult Subjects. 2010. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Lieb, K. Changes of Cerebral Spinal Fluid APPSα Levels Under Oral Therapy With Acitretin 30 Mg Daily in Patients With Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: A Multicenter Prospective Randomised Placebo-Controlled Parallel-Group Study. 2017. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Aphios Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy Assessment of Intranasal Nanoparticles of APH-1105, A Novel Alpha Secretase Modulator For Mild to Moderate Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease(AD). 2021. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Paul, F. Sunphenon EGCg (Epigallocatechin-Gallate) in the Early Stage of Alzheimer´s Disease. 2021. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- AstraZeneca A Single-Center, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, 4-Way Cross-over Study to Assess the Effect of a Single Oral Dose of AZD3293 Administration on QTc Interval Compared to Placebo, Using Open-Label AVELOX (Moxifloxacin) as a Positive Control, in Healthy Male Subjects. 2014. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Eli Lilly and Company Assessment of Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacodynamic Effects of LY2886721 in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease or Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Janssen Pharmaceutical, K.K. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized, 4-Week, Multiple-Dose, Proof of Mechanism (POM) Study in Japanese Subjects Asymptomatic at Risk for Alzheimer Dementia (ARAD) Investigating the Effects of JNJ-54861911 on A-Beta Processing in Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Plasma. 2019. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Janssen Research & Development, LLC A Randomized, Two-Period, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled and Open-Label, Multicenter Extension Study to Determine the Long-Term Safety and Tolerability of JNJ-54861911 in Subjects in the Early Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. 2022. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Multiple Oral Doses of CNP520 in Healthy Elderly Subjects. 2017. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC A Phase III, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Double-Blind Clinical Trial to Study the Efficacy and Safety of MK-8931 (SCH 900931) in Subjects With Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease (Prodromal AD). 2019. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Eli Lilly and Company Effect of γ-Secretase Inhibition on the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease: LY450139 Versus Placebo. 2015. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Eli Lilly and Company Open-Label Extension for Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Who Complete One of Two Semagacestat Phase 3 Double-Blind Studies (H6L-MC-LFAN or H6L-MC-LFBC). 2014. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Effects of BMS-708163 in the Treatment of Patients With Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Wyeth is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Pfizer Ascending Single-Dose Study of the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of GSI-136 Administered Orally to Healthy Japanese Male Subjects and Healthy Japanese Elderly Male Subjects. 2009. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- NeuroGenetic Pharmaceuticals Inc A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Single Ascending Dose Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Orally-Administered NGP 555 in Healthy Young Volunteers. 2016. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- National Institute on Aging (NIA) A Pilot Study of Exendin-4 in Alzheimer s Disease. 2018. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Apostolopoulos, V.; Bojarska, J.; Chai, T.-T.; Elnagdy, S.; Kaczmarek, K.; Matsoukas, J.; New, R.; Parang, K.; Lopez, O.P.; Parhiz, H.; et al. A Global Review on Short Peptides: Frontiers and Perspectives. Mol. Basel Switz. 2021, 26, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahdaripour, M.; Owji, H.; Eslami, M.; Zamani, M.; Vakili, B.; Sabetian, S.; Nezafat, N.; Ghasemi, Y. Selected Application of Peptide Molecules as Pharmaceutical Agents and in Cosmeceuticals. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2019, 19, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, V. Reducing the Cost of Peptide Synthesis. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. News 2013, 33, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic Peptides: Current Applications and Future Directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kametani, F.; Hasegawa, M. Reconsideration of Amyloid Hypothesis and Tau Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brothers, H.M.; Gosztyla, M.L.; Robinson, S.R. The Physiological Roles of Amyloid-β Peptide Hint at New Ways to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, M.; Liu, B.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ma, L.; Lee, K.-W.; Niikura, T.; Nishimoto, I.; Cohen, P. Interaction between the Alzheimer’s Survival Peptide Humanin and Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein 3 Regulates Cell Survival and Apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13042–13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matsuoka, M. Humanin; a Defender against Alzheimer’s Disease? Recent Patents CNS Drug Discov. 2009, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niikura, T. Humanin and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Beginning of a New Field. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2022, 1866, 130024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.; Wan, J.; Mehta, H.H.; Miller, B.; Christensen, A.; Levine, M.E.; Salomon, M.P.; Brandhorst, S.; Xiao, J.; Kim, S.-J.; et al. Humanin Prevents Age-Related Cognitive Decline in Mice and Is Associated with Improved Cognitive Age in Humans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, S.; Hu, X.; Bennett, S.; Xu, J.; Mai, Y. The Molecular Structure and Role of Humanin in Neural and Skeletal Diseases, and in Tissue Regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-P.; Xie, Y.; Meng, X.-Y.; Kang, J.-S. History and Progress of Hypotheses and Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. The Aging Lysosome: An Essential Catalyst for Late-Onset Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics 2020, 1868, 140443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, H.J. Redox-Active Metal Ions and Amyloid-Degrading Enzymes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.-L.; Liu, X.-Z.; Shen, P.; Zheng, Y.-G.; Lan, X.-R.; Lu, C.-B.; Wang, J.-Z. Current Understanding of Metal Ions in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bukar Maina, M.; Al-Hilaly, Y.K.; Serpell, L.C. Nuclear Tau and Its Potential Role in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frost, B.; Jacks, R.L.; Diamond, M.I. Propagation of Tau Misfolding from the Outside to the Inside of a Cell. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 12845–12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harada, R.; Okamura, N.; Furumoto, S.; Tago, T.; Yanai, K.; Arai, H.; Kudo, Y. Characteristics of Tau and Its Ligands in PET Imaging. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M. Molecular Mechanisms in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Tauopathies-Prion-Like Seeded Aggregation and Phosphorylation. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina, M.; Hernández, F.; Avila, J. New Features about Tau Function and Dysfunction. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Šimić, G.; Babić Leko, M.; Wray, S.; Harrington, C.; Delalle, I.; Jovanov-Milošević, N.; Bažadona, D.; Buée, L.; De Silva, R.; Di Giovanni, G.; et al. Tau Protein Hyperphosphorylation and Aggregation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies, and Possible Neuroprotective Strategies. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Bharti; Kumar, R.; Pavlov, P.F.; Winblad, B. Small Molecule Therapeutics for Tauopathy in Alzheimer’s Disease: Walking on the Path of Most Resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 209, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.; Kennelly, S.P.; O’Neill, D. Drug Treatments in Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin. Med. Lond. Engl. 2016, 16, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eli Lilly and Company Assessment of Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of LY3303560 in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Vaz, M.; Silvestre, S. Alzheimer’s Disease: Recent Treatment Strategies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2020, 12, 1179573520907397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herrmann, N.; Chau, S.A.; Kircanski, I.; Lanctôt, K.L. Current and Emerging Drug Treatment Options for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Drugs 2011, 71, 2031–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tifratene, K.; Duff, F.L.; Pradier, C.; Quetel, J.; Lafay, P.; Schück, S.; Benzenine, E.; Quantin, C.; Robert, P. Use of Drug Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease in France: A Study on a National Level Based on the National Alzheimer’s Data Bank (Banque Nationale Alzheimer). Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2012, 21, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlow, M.R.; Cummings, J.L. Effective Pharmacologic Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Med. 2007, 120, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, A. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer’s Disease. Semin. Neurol. 2019, 39, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sramek, J.J.; Cutler, N.R. Recent Developments in the Drug Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging 1999, 14, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.E.; Li, Y.-M. Turning the Tide on Alzheimer’s Disease: Modulation of γ-Secretase. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epis, R.; Marcello, E.; Gardoni, F.; Luca, M.D. Alpha, Beta-and Gamma-Secretases in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Biosci.-Sch. 2012, 4, 1126–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninkilampi, R.; Brothers, H.M.; Eslick, G.D. Pharmacological Agents Targeting γ-Secretase Increase Risk of Cancer and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2016, 53, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Ganeshpurkar, A.; Kumar, D.; Modi, G.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, S.K. Secretase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: Long Road Ahead. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 148, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchlis, V.D.; Melagraki, G.; Zacharia, L.C.; Afantitis, A. Computer-Aided Drug Design of β-Secretase, γ-Secretase and Anti-Tau Inhibitors for the Discovery of Novel Alzheimer’s Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, H.A.; Przemylska, L.; Clavane, E.M.; Meakin, P.J. BACE1: More than Just a β-Secretase. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2022, 23, e13430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombouts, F.; Kusakabe, K.; Hsiao, C.-C.; Gijsen, H.J.M. Small-Molecule BACE1 Inhibitors: A Patent Literature Review (2011 to 2020). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Vassar, R.; De Strooper, B.; Hardy, J.; Willem, M.; Singh, N.; Zhou, J.; Yan, R.; Vanmechelen, E.; De Vos, A.; et al. The β-Secretase BACE1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.; Bhugra, P. Emerging Drug Targets for Aβ and Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shanthi, K.B.; Krishnan, S.; Rani, P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Plasma Amyloid 1-42 and Tau as Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. SAGE Open Med. 2015, 3, 2050312115598250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silvestro, S.; Valeri, A.; Mazzon, E. Aducanumab and Its Effects on Tau Pathology: Is This the Turning Point of Amyloid Hypothesis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J.; Chiao, P.; Bussière, T.; Weinreb, P.H.; Williams, L.; Maier, M.; Dunstan, R.; Salloway, S.; Chen, T.; Ling, Y.; et al. The Antibody Aducanumab Reduces Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2016, 537, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberlein, S.B.; von Hehn, C.; Tian, Y.; Chalkias, S.; Muralidharan, K.K.; Chen, T.; Wu, S.; Skordos, L.; Nisenbaum, L.; Rajagovindan, R.; et al. Emerge and Engage Topline Results: Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, e047259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, L.H.; Lopez, O.L. ENGAGE and EMERGE: Truth and Consequences? Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2021, 17, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failure to Demonstrate Efficacy of Aducanumab: An Analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE Trials as Reported by Biogen, December 2019—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33135381/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Salloway, S.; Chalkias, S.; Barkhof, F.; Burkett, P.; Barakos, J.; Purcell, D.; Suhy, J.; Forrestal, F.; Tian, Y.; Umans, K.; et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in 2 Phase 3 Studies Evaluating Aducanumab in Patients With Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Aisen, P.; Lemere, C.; Atri, A.; Sabbagh, M.; Salloway, S. Aducanumab Produced a Clinically Meaningful Benefit in Association with Amyloid Lowering. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open Peer Commentary to “Failure to Demonstrate Efficacy of Aducanumab: An Analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE Trials as Reported by Biogen December 2019”—Sabbagh—2021—Alzheimer’s & Dementia—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/alz.12235 (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Schneider, L.S. Aducanumab Trials EMERGE But Don’t ENGAGE. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 9, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullard, A. More Alzheimer’s Drugs Head for FDA Review: What Scientists Are Watching. Nature 2021, 599, 544–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Controversy and Progress in Alzheimer’s Disease—FDA Approval of Aducanumab | NEJM. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2111320 (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- What FDA’s Controversial Accelerated Approval of Aducanumab Means for Other Neurology Drugs. Neurology Today. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/neurotodayonline/fulltext/2021/08050/what_fda_s_controversial_accelerated_approval_of.1.aspx (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Aschenbrenner, D.S. Controversial Approval of New Drug to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Nurs. 2021, 121, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. Recently Approved Alzheimer Drug Raises Questions That Might Never Be Answered. JAMA 2021, 326, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.C.; Knopman, D.S.; Emerson, S.S.; Ovbiagele, B.; Kryscio, R.J.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Kesselheim, A.S. Revisiting FDA Approval of Aducanumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. Landmark Alzheimer’s Drug Approval Confounds Research Community. Nature 2021, 594, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlawish, J.; Grill, J.D. The Approval of Aduhelm Risks Eroding Public Trust in Alzheimer Research and the FDA. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillit, H.; Green, A. Aducanumab and the FDA—Where Are We Now? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenholtz Levy, H. Accelerated Approval of Aducanumab: Where Do We Stand Now? Ann. Pharmacother. 2022, 56, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.Y.; Howard, R. Can We Learn Lessons from the FDA’s Approval of Aducanumab? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisticò, R.; Borg, J.J. Aducanumab for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Regulatory Perspective. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 171, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koryakina, A.; Aeberhard, J.; Kiefer, S.; Hamburger, M.; Küenzi, P. Regulation of Secretases by All-Trans-Retinoic Acid. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 2645–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szutowicz, A.; Bielarczyk, H.; Jankowska-Kulawy, A.; Ronowska, A.; Pawełczyk, T. Retinoic Acid as a Therapeutic Option in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Cholinergic Restoration. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-P.; Casadesus, G.; Zhu, X.; Lee, H.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Gustaw-Rothenberg, K.; Lerner, A. All-Trans Retinoic Acid as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sodhi, R.K.; Singh, N. Retinoids as Potential Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 120, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, M.; Kruse, P.; Eichler, A.; Straehle, J.; Beck, J.; Deller, T.; Vlachos, A. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Induces Synaptic Plasticity in Human Cortical Neurons. eLife 2021, 10, e63026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theus, M.H.; Sparks, J.B.; Liao, X.; Ren, J.; Luo, X.M. All- Trans-Retinoic Acid Augments the Histopathological Outcome of Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration in Lupus-Prone MRL/Lpr Mice. J. Histochem. Cytochem. Off. J. Histochem. Soc. 2017, 65, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kapoor, A.; Wang, B.-J.; Hsu, W.-M.; Chang, M.-Y.; Liang, S.-M.; Liao, Y.-F. Retinoic Acid-Elicited RARα/RXRα Signaling Attenuates Aβ Production by Directly Inhibiting γ-Secretase-Mediated Cleavage of Amyloid Precursor Protein. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.-K.; Park, H.-J.; Hong, H.S.; Baik, E.J.; Jung, M.W.; Mook-Jung, I. ERK1/2 Is an Endogenous Negative Regulator of the Gamma-Secretase Activity. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2006, 20, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, M.R.; Yousefi, K.; Esmaeili, A.; Ghasemnejad-Berenji, M. The Role of ERK1/2 Pathway in the Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Overview and Update on New Developments. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Dockendorf, M.F.; McIntosh, I.; Xie, I.; Breidinger, S.; Meng, D.; Ren, S.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, L.; Roadcap, B.; et al. An Investigation of Instability in Dried Blood Spot Samples for Pharmacokinetic Sampling in Phase 3 Trials of Verubecestat. AAPS J. 2022, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockendorf, M.F.; Jaworowicz, D.; Humphrey, R.; Anderson, M.; Breidinger, S.; Ma, L.; Taylor, T.; Dupre, N.; Jones, C.; Furtek, C.; et al. A Model-Based Approach to Bridging Plasma and Dried Blood Spot Concentration Data for Phase 3 Verubecestat Trials. AAPS J. 2022, 24, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahrudin Arrozi, A.; Shukri, S.N.S.; Mohd Murshid, N.; Ahmad Shahzalli, A.B.; Wan Ngah, W.Z.; Ahmad Damanhuri, H.; Makpol, S. Alpha- and Gamma-Tocopherol Modulates the Amyloidogenic Pathway of Amyloid Precursor Protein in an in Vitro Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Transcriptional Study. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 846459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, A.; Chiricosta, L.; Silvestro, S.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. α-Tocopherol Modulates Non-Amyloidogenic Pathway and Autophagy in an In Vitro Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Transcriptional Study. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimm, M.O.W.; Mett, J.; Hartmann, T. The Impact of Vitamin E and Other Fat-Soluble Vitamins on Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishida, Y.; Ito, S.; Ohtsuki, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Takahashi, T.; Iwata, N.; Jishage, K.-I.; Yamada, H.; Sasaguri, H.; Yokota, S.; et al. Depletion of Vitamin E Increases Amyloid Beta Accumulation by Decreasing Its Clearances from Brain and Blood in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33400–33408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lloret, A.; Esteve, D.; Monllor, P.; Cervera-Ferri, A.; Lloret, A. The Effectiveness of Vitamin E Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Browne, D.; McGuinness, B.; Woodside, J.V.; McKay, G.J. Vitamin E and Alzheimer’s Disease: What Do We Know so Far? Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farina, N.; Llewellyn, D.; Isaac, M.G.E.K.N.; Tabet, N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD002854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysken, M.W.; Sano, M.; Asthana, S.; Vertrees, J.E.; Pallaki, M.; Llorente, M.; Love, S.; Schellenberg, G.D.; McCarten, J.R.; Malphurs, J.; et al. Effect of Vitamin E and Memantine on Functional Decline in Alzheimer Disease: The TEAM-AD VA Cooperative Randomized Trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Anastasiou, A.I.; Zachariou, V.; Pelidou, S.-H. Reasons for Failed Trials of Disease-Modifying Treatments for Alzheimer Disease and Their Contribution in Recent Research. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reiss, A.B.; Glass, A.D.; Wisniewski, T.; Wolozin, B.; Gomolin, I.H.; Pinkhasov, A.; De Leon, J.; Stecker, M.M. Alzheimer’s Disease: Many Failed Trials, so Where Do We Go from Here? J. Investig. Med. Off. Publ. Am. Fed. Clin. Res. 2020, 68, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-M.; Shen, J.; Zhao, H.-L. Major Clinical Trials Failed the Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Insights from Two Decades of Clinical Trial Failures—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35342092/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Ito, K.; Chapman, R.; Pearson, S.D.; Tafazzoli, A.; Yaffe, K.; Gurwitz, J.H. Evaluation of the Cost-Effectiveness of Drug Treatment for Alzheimer Disease in a Simulation Model That Includes Caregiver and Societal Factors. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2129392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versijpt, J. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of the Pharmacological Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 2014, 42 (Suppl. 3), S19–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Franco, D.; Perez, A.; Harrington, C. The Effect of Pramlintide Acetate on Glycemic Control and Weight in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and in Obese Patients without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, S.; Spampinato, S.F.; Lim, D. Molecular Aspects of Cellular Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Need for a Holistic View of the Early Pathogenesis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, S.; Yang, F.; Sivils, A.; Cegielski, V.; Chu, X.-P. Amylin and Secretases in the Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12070996

Singh S, Yang F, Sivils A, Cegielski V, Chu X-P. Amylin and Secretases in the Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules. 2022; 12(7):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12070996

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Som, Felix Yang, Andy Sivils, Victoria Cegielski, and Xiang-Ping Chu. 2022. "Amylin and Secretases in the Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease" Biomolecules 12, no. 7: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12070996

APA StyleSingh, S., Yang, F., Sivils, A., Cegielski, V., & Chu, X.-P. (2022). Amylin and Secretases in the Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules, 12(7), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12070996